|

CCC Forestry

|

|

Chapter VIII

FOREST MENSURATION

|

FOREST mensuration is the science of measuring the contents of standing or felled timber, and estimating growth and yields. Foresters, timber owners, and farmers owning woodlands should know the essentials of timber measurement. A pioneer storekeeper who believed that "a pint's a pound the world around" developed a sizable trade in shot with local hunters. He more than likely failed as a merchant. Likewise timber owners, who do not recognize the value of forest mensuration, may make transactions in forest products to their own disadvantage, but to the decided advantage of dealers. When there was an abundance of low-cost timber and cheap labor, lumbermen did not find it necessary to make precise measurements. Transactions involving vast timbered areas were based on superficial estimates. Today, however, because of limited quantities of timber and increased production costs, timbermen, in keeping with present business practice, find it necessary to make closer estimates of timber volume. |

Knowledge of Measurement Is Essential.

| |

|

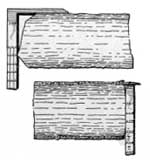

UNITS OF MEASUREMENT The board foot: A knowledge of the basic units of measure is necessary before an attempt can be made to learn the processes of mensuration. The unit of measure for lumber is the board foot. A board foot is a piece of wood 1 foot square and 1 inch thick, or its equivalent. A board an inch thick, 12 inches wide, and 10 feet long contains 10 board feet. An inch board 8 inches wide and 18 feet long contains 12 board feet; a 2-inch plank 6 inches wide and 8 feet long contains 8 board feet. Volumes of boards less than an inch thick are usually estimated as if they were an inch thick.

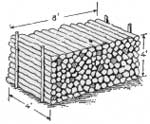

The cord: Fuel wood, pulpwood, and similar bulk wood is measured by the cord. A standard cord is a stack of wood 4 feet wide, 4 feet high, and 8 feet hong. It has a cubical measure of 128 cubic feet, but there are spaces between the pieces of wood in the stack. The actual volume of wood is from 70 to 90 cubic feet. Seasoning may reduce the actual wood content of a cord of green wood as much as 10 or 15 percent. Some pulpwood is cut 5 feet long, and fuel wood is cut less than 4 feet long, depending on sizes of stoves and fireplaces. Such wood regardless of length, stacked 8 feet long and 4 feet high, is commonly called a cord, although it is not standard size. Piece measurement: Some wood products are sold by the piece. Poles, piles, posts, ties, and staves are in this classification. Poles and piles are cut in different sizes governed by particular needs. Posts have no exact dimensions, but a standard post is said to be 4 inches thick, 5 inches wide, and 7 feet long. Standard railroad ties are 7 inches thick, 9 inches wide, and 9 feet long. These products are bought by the piece. Stave and shingle bolts are bought by the hundred. Cubical measurement: Very valuable woods, such as mahogany or dyewoods, are usually measured by the cubic foot. A cubic foot is a solid, a foot long, a foot wide, and a foot thick. Acreage: Stumpage (standing timber) is sometimes measured and bought by the acre. This is more common for pulpwood measurement than for other products, and is used extensively by large paper-mill operators of Canada. |

See Timbers, pp. 152, 155.

| |

|

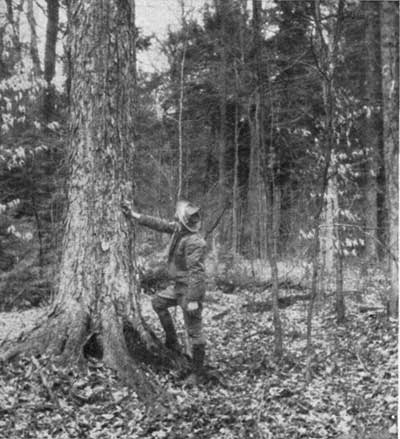

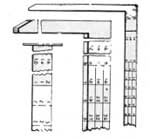

Estimating the volume of standing timber is known as cruising. The most reliable method of cruising is based upon a systematic use of measuring instruments and practices. This is called the systematic cruise. The volume of the trees on a representative or average portion of the forest is estimated, and the total volume calculated, based upon the volume of the part which was measured. CRUISING INSTRUMENTS The amount of wood in a tree is determined by measurement of its diameter and height. Special instruments have been developed for use in cruising. It is desirable that one be acquainted with those commonly used. Diameter measurement: For measuring diameters, the caliper is the most common instrument. It is a heavy rule usually about 3 feet long, but longer for use on the very large trees. At one end of the rule a rigid arm extends at right angles, the rule and the fixed arm forming an L. Another sliding arm is attached also at right angles to the rule. The caliper is opened and the arms placed on each side of the tree trunk. The sliding arm is then moved close against the trunk, and the diameter read on the graduated (marked in units) ruler. If a tree trunk is oval instead of round, the longest and the shortest diameters are taken and averaged. A tape may also be used to take diameter measurement. The circumference of the tree is measured and the diameter calculated by dividing the circumference by 3.1416. This is based on the fact that for every inch in the diameter of a perfect circle there are 3.1416 inches in the circumference. Diameter tapes on which these calculations may be read are available. With these tapes the cruiser reads diameters of the trees, instead of inches in circumference. Large trees may be measured by attaching the hooked end of the tape to the bark and running the tape around the trunk. With a tape, however, it is impossible to average the diameters of trees having oval-shaped trunks. A small fraction of their measurement is deducted if the tree has an oval shape.

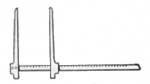

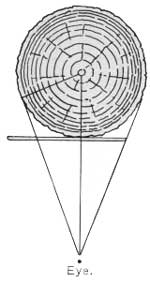

The Biltmore stick is a rule graduated to indicate the diameter of a tree. The rule is placed against the trunk of the tree at a tangent. With the eye about 25 inches away (average arm length), the diameter may be read by lining up the end of the stick with the line of vision to one side of the trunk and sighting across the rule to the other side. At the point where the line of vision crosses the stick, the graduation will indicate the diameter of the tree. Height measurement: Heights of trees may be measured by an Abney hand level. The Abney is a pocket instrument for measuring angles or per cent of elevation. (See chapter on Forest Engineering.) For tree measurement, the scale on the instrument should indicate elevations in percent; that is, it should be equipped with a percentage arc or limb. The operator of the level stands a hundred feet from the tree and sights the instrument at the top of the tree or at the merchantable height. Then without moving the instrument, the level bulb attached to the side is adjusted to a level (horizontal) position. An indicator on the level tube indicates the percent of elevation on the graduated arc. The instrument is then sighted on the base of the tree and the percentage read. These two readings are added (subtracted if the eye of the instrument operator is below the base of the tree) and the sum (or difference if subtracted) of the two readings is the height of the tree in feet. There are many phases of measurement with the Abney impossible to describe in limited space. For details and full instructions, see Forest Mensuration by Bruce and Schumacher1 or an Abney Handbook.2

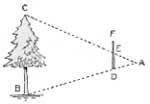

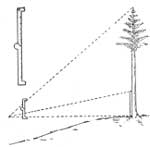

An instrument for measuring heights of trees is called a hypsometer. There are many kinds of hypsometers, but only a few will be mentioned. The Forest Service hypsometer is probably the best one on the market. It works on the same principle as the Abney level, but a gravity bob, instead of a level bulb, is used to indicate the tree's height. The little plumb bob and the graduated arc are enclosed in a case. On one side of the case is an eye piece or peep hole and on the other side a little window through which the tree top may be seen. Sighting at the top of the tree at a distance of 100 feet from its base, the operator reads the tree's height on the movable scale. The Merrit hypsometer is a very simple one, consisting of a rule graduated somewhat like the Biltmore stick, previously described. The cruiser, using a Merrit hypsometer, faces the tree at a fixed distance (usually 66 feet) holding the rule vertically at arms length. He holds the base of the rule on his line of sight to the base of the tree, sighting just under the bottom of the upright rule to the base of the tree. Without moving the rule or changing his position, he sights at the top of the tree. The marking on the rule which lies in his line of sight to the top of the tree will indicate the height of the tree. The Christen hypsometer is another simple instrument consisting of a rule or scale about 10 inches long which may be folded and carried in the pocket. The cruiser, facing the tree at sufficient distance to permit him to see its top and base, holds the instrument vertically before him. An assistant holds a 10-foot pole upright at the base of the tree. The cruiser moves the scale nearer or away from the eye until the whole length of the scale just covers the entire view (in height) of the tree. The marking on the scale which is on the line of sight with the top of the upright pole indicates the height of the tree. CRUISING PRACTICES Although cruising may be done by one experienced cruiser alone, he usually has a crew of assistants. Their job is to measure the diameters and heights of trees in a portion of the forest and to estimate total timber volumes from this data. In most cruises only enough height measurements are taken in each species to make height tables. By taking both diameter measurement and height measurement on a sufficient number of trees, average heights for different diameters in each species may be found. For example, in a definite locality, yellow pines with 16-inch diameters will average 38 feet of merchantable height, and trees of the same species having 20-inch diameters will average 46 feet of merchantable logs. In the same locality it may be found that red oak with 16- and 20-inch diameters average 28 and 35 feet, respectively. After such local tables are made, it is necessary only to measure diameters. Heights are then calculated from the tables. In cruises requiring more precision, each tree height may be measured separately. On cruises requiring less precision, all heights may be estimated by eye. The systematic cruise: Under the systematic method, it is necessary for men to work in crews. The average-sized crew is composed of an experienced cruiser and three assistants, but three-man crews may work on some estimates, and a five- or six-man crew may also work to advantage, especially where hypsometer measurements are taken.

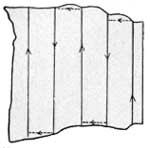

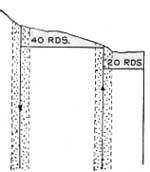

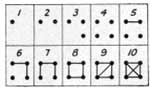

A CREW AT WORK A four-man timber estimating crew using the strip method works somewhat as follows: A compass man, using a Forest Service compass, or a hand compass, starts on a compass line through the woods about 20 rods from one of the boundary lines of the tract. He goes up the slope of a hill rather than along the side because different altitudes and soils affect the size of trees, and better samples of the stand are obtained by this method than by working along the sides of slopes. The compass man drags a surveyor's chain tied to his belt as he walks along his course. The chief of the party, an experienced man, follows at the end of the chain and halts the compass man when one chain has been measured. These two men stop, and the forward man takes notes on topography, streams, and roads, and makes a rough map of the forest. Beginning at the rear end of the chain, each caliper man paces off two rods on each side, or the leader, who acts as a tally man, assists in measuring this distance. The caliper men then begin measuring the diameters of the trees and calling out their sizes to the tally man, who records them in his tally book. Defective trees are calipered and called, even if they are culls (trees unfit for lumber). One caliper man may call, "White oak, 23." The tally man records this in his tally book. The caliper man on the other side of the line then calls "Yellow poplar, 34." This is tallied and the first caller reports, "Maple, 19," and the second one, "Beech, 28, cull." No fractions of inches are called, because in diameter measurements such fractions are disregarded. Instruments are read to the nearest inch. If actual measurement falls on a half-inch mark, the nearest even inch is read. For example, both 19-1/2 and 20-1/2 are read as 20, or 21-1/2 and 22-1/2 as 22. (In height and length measurements, the same practice is applied to feet and fractions of feet.) The diameters are measured about 4-1/2 feet from the ground. This height is handy for the workmen and is above the swell of the stump. This is called "diameter breast high" and is often abbreviated to D. B. H. All the trees above a minimum diameter on the four-rod strip are Strip method, measured and recorded. The tally man walks along the compass line and inspects defective trees, estimating the usable part in each. If hypsometer readings are also being taken, two men usually work on each side of the compass line, one measuring diameter, the other estimating height of a tree at the same time. Two measurements are called to the tally man instead of one. When the forward end of the chain is reached, the compass man moves forward again; the leader follows and halts him when the end of the chain reaches the mark made on the ground by the compass carrier at the position of the first halt. The procedure of measuring and tallying is repeated until the opposite boundary of the forest is reached. After the strip is finished, the compass operator, with the help of another man, chains off 40 rods at right angles to the line just run. This is the center line of the return strip to be run back across the forest, Strips spaced at this distance give a 10 percent estimate of the whole forest. For a 20 percent estimate, the compass lines are spaced 20 rods apart (or 10 rods apart when the strip is reduced to 2 rods in width). The plot method: Some cruises are made by the plot method rather than by strips. Under the plot methods the compass line is run as described in cruising strips. Plots are measured at certain distances apart along the line, instead of in a continuous strip. The plots may be square, circular, or oblong. The square acre may be paced (70 yards on each side) by the compass man. The circular acre has a radius of 118 feet or 39-1/3 yards. The oblong acre—1 chain wide (66 feet) and 10 chains long—is probably most practical. This can easily be measured along the compass line and trees calipered as in the strip method. The percentage of trees to be measured in the cruise will determine the distance between the plots. Smaller plots of one-half to one-eighth acre are often used. The ocular cruise: An expert cruiser may be able to make a fair timber estimate without the systematic use of instruments. He walks through the stand and examines the trees. By carefully noting the sizes and numbers of trees, he can make an estimate. Such a method of cruising is called the ocular method, because the eye is principally used to estimate sizes. The estimator, under this system, may carry pocket instruments, such as hypsoineter and diameter tape, to check tree measurements. He may locate sample plots with average stand, pace off an acre, and count the average-size trees, thus arriving at an estimate of the total volume. Each cruiser uses his own methods based upon his experience and practice. The sample cruise: The sample method of cruising requires enough systematic measurement to find the volume of the sample tree of each species in a forest or locality. The sample tree is an average-size tree of any one species. After the sample is found, cruising consists of counting trees only. This may be done on strips or plots as desired. Sometimes, when no average sample has been found, counts may be made, every twenty-fifth or fiftieth tree measured, and when the entire count is completed the average volumes calculated from the trees measured.

For extensive counting the cruiser carries a mechanical counter which fits in the hand. A small lever is pressed with the thumb to register each tree. The total number is recorded and may be read from a dial on the instrument and recorded. The counter registers up to 999 and then repeats. One cruiser may make counts in two species at the same time by carrying a counter in each hand. Aerial estimation: Although timber cruising by aerial photography is in its infancy, many foresters believe that it has great possibilities. A series of vertical pictures covering the entire forest area are taken from an airplane (the camera being directed straight down). These are mounted, oriented, and fitted to show a complete photograph of the forest. Elevation, streams, trails, and other landmarks stand out clearly, and different species and timber types may be identified if the pictures are taken in spring while leaf colors are fresh or in late autumn before leaves fall. Aerial photographs are used principally in mapping and locating types and stands. After they are located, direct measurement is taken to get averages in each type. Rule of thumb: Foresters and woodsmen know rules of thumb by which they can estimate the contents of a tree or log in board feet without the use of a volume table. A rule of thumb is a simple formula which may be easily applied in measurement. Probably the most common one is based upon Doyle's log rule, explained later. It gives the volume of a standard 16-foot log. The rule of thumb is as follows: Subtract 4 inches from the diameter of the small end of the log inside the bark, and square the remainder. The result is the board-foot content of the log. If the tree has more than one log, the average diameter inside the bark should be estimated, and the same calculations made. Multiply the results by the number of 16-foot logs in the tree. For instance, a tree with a 40-foot merchantable trunk would contain two and a half 16-foot logs. This rule gives high results for a three- or four-log tree. The small-end diameter of each 16-foot log in such trees may be estimated. The 4 inches deducted from the diameter under Doyle's rule is to compensate for sawdust and slabs—waste products of the sawmill operation. Volume tables: For converting the measurement of diameters and heights of trees in a stand to board feet of lumber, volume tables are used. Such tables show how many board feet of lumber can be sawed from trees of different diameters and heights. Volume tables are most accurately made by measuring a number of trees carefully, following each of them through the mill, and measuring the volume of lumber sawed from each one. In this way the amount of lumber which can be expected from trees of certain size is known, and the number of board feet of lumber in a forest may be estimated. |

Diameter Tapes.

Hypsometers.

Calipering Trees. Tallying.

Square, Oblong, or Circular Acres.

Experience Instead of Instruments. Each Ocular Cruiser Uses Own Methods. The Sample Method.

Photograph from an Airplane.

Aerial Photography Valuable in Forest Mapping. Rule of Thumb Simplifies Volume Calculation.

| |

|

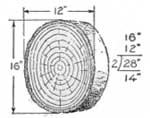

Mensuration is used for other purposes than determining timber volume. Growth studies demand exceptionally close measurements both in diameters and heights. The results of such studies are valuable in making cutting plans, in solving management problems, and in determining forest policy. Much of the research which has made the science of forestry possible is based upon accurate measurement. The farmer harvests his crops annually, measuring the yield and determining his profit or loss. The forester or timber grower has to wait long periods to check his harvest. It becomes necessary, therefore, for him to make growth studies to see what forest stands are yielding. Some stands may be increasing in growth so slowly that they are not profitable. Forest increment (increase in volume) may be calculated by accurate measurement. Counting rings: The sizes of trees at various ages in a particular stand may be found by measuring a number of trees, determining their ages, and relating age to size. If the study is being made on a plantation, a record of the age of trees should be available. If not, the best method of determining age is by counting growth rings. Each spring a tree adds a spongy growth just under the bark. In summer, a firmer growth overlays this first one. This growth of springwood and summerwood together forms an annual ring. These rings may be counted on cross cuts of tree trunks to determine the age of the tree. The stump of a freshly cut tree shows the rings very plainly. It would be a wasteful practice to fell trees in order to count rings, and leave them on the ground to rot. If trees are cut to make growth studies, arrangements should be made for using the timber. It is sometimes possible to combine a growth study with a logging operation. Rings may be counted on the stumps and logs, and diameter measurements taken inside the bark with an ordinary rule. Boring: Where it is not possible to make studies on logging operations, precise measurements in diameter and height are made, and ages are found by use of an increment borer. This is a gimletlike instrument for boring into the side of the tree. It has a hollow bit that bores out a "core" of wood on which the rings may be counted. It is not necessary to draw a core all the way from the center of large trees. The number of rings per inch is calculated, and ages of trees thus computed. The increment borer makes a small hole which soon closes and does not seem to damage trees. Sometimes the hole is plugged with grafting wax to prevent the entrance of insects or diseases. Yields: Rainfall, temperature, and soil conditions greatly affect the growth of forests. The normal yield is the yield obtainable from a completely stocked acre of healthy trees in the locality. The empirical yield is the average increase per acre obtainable from the actual stand of the forest. Yield tables: Data obtained by growth measurements may be used to make yield tables from which future yields may be predicted. After the average sizes of trees of certain ages have been found, they are plotted on cross-section paper—sometimes called graph paper—and used in making the tables. On a sheet of cross-section paper, volumes are plotted on vertical squares and ages on horizontal squares. Curves for determining averages are plotted. The same methods are used in making volume tables either for trees or for logs (log rules). In cruises, heights and diameters may be plotted to obtain average heights for certain diameters. Unless one is fairly familiar with calculations by means of cross-section charts, it is impossible to explain formation of tables in a limited space. Refer to any good text book on Forest Mensuration3 for detailed explanation of these graphic processes.

TIMBER SURVEYS A timber survey extends over large areas. In making such a survey several cruising crews may work out of the same headquarters or camp, moving from one location to another. Forest areas are located, stands measured and classified, and yields predicted. Tables and maps are made as a record of the survey. The forest survey, although based on forest mensuration, includes other factors than the actual timber growth, or increment. Soils, drainages, and other factors affecting forest production are studied, in addition to timber stands. The crews of a forest survey may be composed of engineers, foresters, and soil experts and their assistants. The forest survey is used extensively by the United States Forest Service in land acquisition. Surveys reveal facts necessary in purchasing areas to be converted into national forests. |

See pp. 6, 7.

Annual Rings as Shown by Increment Cores. Determining the Yield.

| |

|

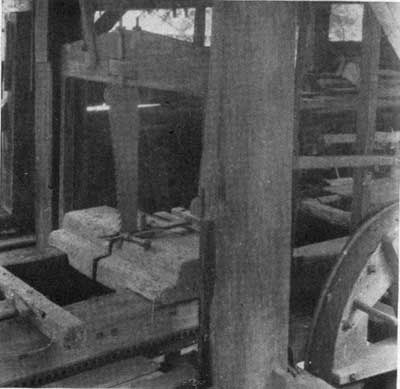

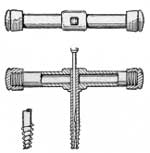

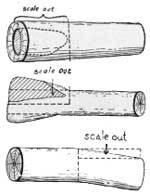

The measuring of logs to determine their volume in board feet is called scaling. Logs may be scaled where they are cut in the woods, on landings or skidways, or at the mill. Since log-cutting crews are usually paid by the thousand board feet, scalers may measure logs where they lie, as a basis for paying the crews. They may be scaled on skidways as a basis for paying snakers or haulers, and at the mill as a mill check. In connection with log sales, logs are usually scaled by a representative of each party to the contract. Log rules have been made to facilitate measuring the contents of logs. By measuring the diameters and lengths of logs, and referring to the log rule, the volume of lumber contained in a log of any size may be found. Scales: Log scales or "scale sticks" have been devised which simplify scaling practice. They are used to measure diameters and lengths and to estimate volumes. There are many different scales, based upon various log rules, but they are basically the same and are used in the same manner. A scale stick is a rule 3 to 4 feet long, somewhat like a common yardstick. It is made of tough hickory or maple, and has a handle at one end and a protecting brass tip at the other. On some of the tips there are L extensions which aid in holding the scale on the end of logs. Others have short, sharp hooks or spurs which may be forced between the bark and the wood. They help to hold the scale on the log and aid in taking the D. I. B. (diameter inside bark) measurements. Scale sticks are marked in feet and inches along both edges. These graduations are used in measuring the logs. The log-rule values are placed on the sides of the sticks, one row of figures indicating board measures of logs of given lengths and diameters. Using the stick: The scaler places the stick on the small end of a log. If, for instance, the figures on the edge of the stick show that the log is 17-1/2 inches D. I. B., he calls this 18 inches. A fraction of an inch is read thus to the nearest even inch. The figures on the side of the stick near the 18-inch mark indicate volumes for different lengths. If the log is 12 feet long, the scaler locates the figure in the row of volumes for 12-foot logs—160 board feet. Variety of scales: There are 20 to 30 different log scales in use in the United States, based on different log rules. The Doyle, Scribner, and Spaulding are well-known scales, and many States have adopted legal scales. These are known by the name of the State, for example, the Maine scale. Log-scale values differ. Some of the differences are radical for certain sizes. An expert in forest mensuration states that the use of different scales may make from 5 to 50 percent difference in the scaled contents of the same log.4 The Doyle scale deducts 4 inches from the diameter of the log for mill waste. The scale of a 16-foot log with a diameter of 8 inches is reduced 75 percent by this deduction. It is evident that this is too great a reduction. No mill should waste three-fourths of an 8-inch log in sawing. The Doyle rule gives a low scale for logs less than 28 inches in diameter.

The Scribner scale seems to be more reliable. On larger logs, however, it has been found by mill tallies that the scale is low. On a 34-inch log, the Scribner scales 100 feet less than the Doyle rule. It is marked in decimals (units of 10 feet) rather than in exact measures. A mark of 9 on this scale indicates a volume of 85 to 95 feet; a mark of 15 indicates a volume of 145 to 155 feet. In a number of logs scaled by a decimal scale, some may be high, and some low, but the average will be the multiple of 10: Thus the two examples would average 90 and 150 feet respectively, and would be so tallied. Log dealers and mill men use a combination of these two rules in the Doyle-Scribner scale. This makes use of the principle of the former rule up to 28-inch diameters and the latter for larger logs. Thus the portions of each rule have been used which favor the mill owners, often to the disadvantage of the timber producer. Logs may be scaled by a rule of thumb when logs rule or scale sticks are not available. The rule given for the estimation of tree volume (p. 177) may be used. Diameters of logs may be measured with any convenient instrument and the rule of thumb applied to get volumes of logs of each dimension. Scaling defective logs: When logs have visible defects which would decrease the lumber volume, defective parts are "scaled out." Logs with excessive defects may be rejected as culls, If enough of the log can be utilized to justify sawing, deductions are made for the defective part. Rots, hollows, crooks, windshakes, cracks, and sometimes other minor defects are scaled out. The part of the log which cannot be used is measured and subtracted from the volume of a sound log of the scale dimension. Overrun: Some sawmills have considerable overrun of lumber above the scale of the logs. A band sawmill, using a thin saw, can get more lumber from a log than a mill using a thicker saw. The circular saw cuts an average kerf of about three eighths inch, while the band saw cuts less than one-fourth inch kerf, The sawyer, by expert handling of the log, can raise the overrun. A log 16 feet long has a greater diameter at one end than. at the other, and since the average diameter is used in scaling, several 10- or 8-foot boards which are not included in the scale can be sawed from this log.

Forest Service practice: The United States Forest Service has adopted standard scaling regulations to be followed in measuring national forest timber. The Scribner decimal C scale is used, and definite instructions are given for scaling out defects. The scaling practices are fair to purchasers and provide for a small overrun. Complete regulations of Forest Service scaling may be found in the book of instructions for scalers.5

|

D. I. B.

Log Scales Not Standardized.

Overrun.

| |

|

AN EXAMPLE OF PRACTICAL FOREST MENSURATION A forest owner has an area of matured timber that he wants to sell. Before advertising it, he employs an experienced timber cruiser to make an estimate of the quantity of timber on the area. The cruiser goes into the woods alone, and by using pocket instruments for occasional checks on diameters and heights, and by counting trees on average plots which he has paced off, he calculates the volume of saw timber per acre. By examining records of previous surveys of the area, the cruiser determines the total acreage of the tract of land. He calculates the total volume of timber and reports to the timber owner. The owner advertises his timber for sale. He sets a stumpage price. A timber dealer needs the timber, but it is necessary for him to buy close, because poor markets force him to sell at a low margin of profit. He asks permission of the owner to make a systematic cruise of the area. With this permission, the dealer sends a crew into the woods to make a closer estimate. The crew uses the strip method, measuring the merchantable trees on 10 percent of the area. Diameter readings are taken by calipers, and local volume tables are used to convert diameter readings to volumes in board feet. After the systematic estimate is finished, the dealer concludes that he can afford to pay the asked price, since his estimate is higher than that made by the first cruise. The transaction is made, and the logging operation begins. The dealer goes into the woods himself, and with other timbermen in his employ, marks the trees to be cut, being very careful to mark only the trees above the diameter minimums specified in his contract. Men are employed to fell and buck the trees. Each sawing crew fixes its mark on the timber which it has cut. Every day or two, a log scaler employed by the dealer, scales the timber cut by each crew and enters it on a record sheet which he turns over to the the pay-roll clerk. After the timber has been cut, it is snaked to skidways by contract loggers. It is unnecessary to rescale the timber as a basis for paying the skidders, because the scaler has marked the scale of each log on its end. Meanwhile the dealer has sold his timber to a mill owner several miles away. The mill has its own equipment for transporting the logs. They are scaled at the skidway by a competent scaler employed by the mill and the dealer himself. They agree on the scale of defective logs, sometimes having rather heated arguments as to whether a log is merchantable or is a cull. The timber has changed ownership twice and its volume has been estimated in board feet several times, but it is still to be measured many times. The mill owner, as a check on his scale and as a matter of business record, measures the exact volume of sawed timber that he obtains from the logs. The use of forest mensuration is apparent. Further measurement of the timber would be classified as scaling lumber. |

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

ccc-forestry/chap8.htm Last Updated: 02-Apr-2009 |