|

THE STONE WALL: FRENCH'S ATTACK

Sumner's troops lay, cold and a little nervous, in the crowded lee of

the city's houses, which hid all but their pickets from the

Confederates. A hard frost the previous night had robbed them of much of

their sleep, but they could neither warm themselves nor even boil

coffee, lest the smoke from their fires reveal their numbers and draw

fire. Many who had wandered away from their commands the night before

had not returned. After sleeping with muddy feet in the beds of absent

citizens, they resumed rummaging through the homes, pilfering whatever

they fancied and vandalizing what they pleased. At the bridgeheads

stood growing mountains of property confiscated from those brazen

skulkers who tried to carry their plunder to the rear.

According to the morning's orders the commander of the Second Corps,

General Couch, had formed William French's division along Fredericksburg's

outermost streets. French's three brigades consisted of thirteen

regiments from every state between Connecticut and the Wabash, including

Delaware and West Virginia. Most of them had seen the Peninsula and

Maryland campaigns, but the four biggest regiments consisted of

nine-month militia men from Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

|

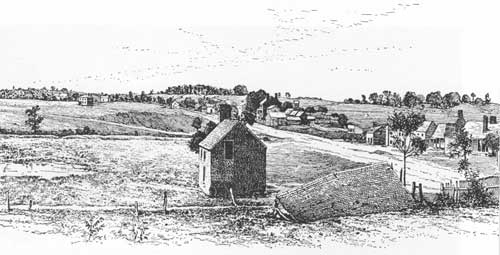

IN ORDER TO REACH MARYE'S HEIGHTS, UNION

SOLDIERS HAD TO CROSS AN OPEN PLAIN NEARLY ONE-HALF MILE IN LENGTH. NOT

ONE REACHED THE STONE WALL. (NA)

|

Just beyond French's waiting lines the houses petered out and a broad

plain opened, cut by a millrace that skirted the city's perimeter.

Normally this waterway would have been full, but Federal engineers had

partially closed the floodgate and drained the sluice somewhat. On the

far side of the ditch the ground rose sharply, offering protection from

enemy fire, and a quarter mile beyond that sat Marye's

Heights and the sunken Telegraph Road. In that road crouched Thomas R.

R. Cobb's Georgia brigade and the 24th North Carolina, their ranks

hidden by the retaining wall. Another rank of Confederate infantry

supported artillery that topped the crest, as well. William Street ran

from the heart of the city toward the Sunken Road,

passing beyond it to become the Orange Plank Road; Hanover Street

paralleled it a couple of blocks to the south. The bridges on those

streets and one other provided the only means of crossing the icy

millrace, so when French received his final orders for the assault he

filed his brigades across them. James Longstreet had spent nearly three

weeks perfecting his defenses on Marye's Heights. Just before the battle he

had spoken to his artillery chief about using an overlooked cannon,

suggesting that he place it to bear on the broad plain behind the city.

Years later Longstreet remembered that his artilleryman

assured him that the plain was already closely covered, promising that

"a chicken could not live on that field when we open on it."

|

JAMES LONGSTREET (USAMHI)

|

Shortly before noon Longstreet directed his gunners to begin

dropping shells into the streets where he could see Union soldiers,

hoping to create a diversion for Jackson's benefit. The moment he chose

to open fire happened to be the same instant that French's skirmishers

began jogging out of the city, with the dense, dark brigades following.

Longstreet felt the sensation of having upset a beehive.

The skirmishers trotted across the ditch on one good bridge, but the

boards of the other had been taken up and hundreds of men had to tiptoe

across on the stringers. Meanwhile, shells from batteries

on the heights began bursting in the ranks.

Once across the ditch, French formed his first brigade under the

protection of the long bluff, and when he gave the word nearly two

thousand men surged grimly forward with rifles on their shoulders and

bayonets fixed. A hail of shell burst immediately from the heights,

blowing great gaps in the ranks, but the Federals pounded onward

without pausing to fire a shot, hoping to close with the enemy quickly.

Muddy ground sucked at wet brogans with every step the Yankees took.

Their entire route lay uphill, with the grade worsening steadily. Heavy

overcoats, equipment, and ammunition bore down on those winded

Northerners, and occasionally they had to stop to tear down fences. All

the while iron burst and flew about them, changing from shell to

canister that swept their lines like gigantic shotgun blasts. The

gasping, sweating survivors reached a second shelf of land a hundred

yards from the Sunken Road, and here they lingered another moment.

Burnside supposed that the greatest impediments to his advance were

those he could detect with his binoculars: the artillery on the heights

and the unprotected second line of infantry. Although Burnside and many

of his subordinates had sojourned in Falmouth and Fredericksburg the

previous summer, no one seems to have counted on the millrace or the

hundreds of riflemen hidden in the Sunken Road. As soon as French's leading

brigadier waved his men over that last swale they were met by a blinding

flash and a deafening din, as though they had been struck by a

lightning bolt. Pale blue overcoats reeled, fell, and tumbled, and the

whole line staggered, wavering like a ribbon in the wind. More crashing

volleys drove them back to the swale, and that was as

far as they would go. The brigadier, Nathan Kimball, quickly calculated that a

quarter of his troops had already fallen; the survivors threw themselves

down and started firing futilely into the cloud of smoke before

them.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

FRENCH ATTACKS MARYE'S HEIGHTS, DECEMBER 13, NOON—1 P.M.

At noon French leaves the town, forms his division in the shelter of the

millrace, and advances to attack Marye's Heights. Kimball's brigade

leads the attack, followed by Andrews and Palmer. They are stopped short

of their objective by Cobb's infantry brigade in the Sunken Road and by

the Washington Artillery on the heights. As the attacks develop, Cooke's

brigade moves up to the crest of the ridge to support Cobb's men in the

road below.

|

General Kimball glanced behind him in time to see the next brigade rise

over the bluff and trot forward, heads bowed before the gale of

canister. The script called for

this next brigade, under Colonel James Andrews, to hang 150 yards behind

Kimball, and when Andrews reached that distance he called a halt. He had

but three regiments left (his own, the 1st Delaware, had gone in with

the skirmishers), and as these Yankees stood to fire over their

comrades' heads the Confederates rained iron and lead on their exposed

position. Before long Colonel Andrews moved his men up

to mingle with Kimball's in the meager cover of that last shallow swale.

About then a bullet snatched General Kimball's right leg from under

him.

|

THE ATTACK ON MARYE'S HEIGHTS: A CONFEDERATE PERSPECTIVE

At dawn the next morning, 13th, in the fresh and nipping air, I

stepped upon the gallery overlooking the heights back of the little

old-fashioned town of Fredericksburg. Heavy fog and mist hid the whole

plain between the heights and the Rappahannock, but under cover of that

fog and within easy cannon-shot lay Burnside's army. Along the heights,

to the right and left of where I was standing, extending a length of

nearly five miles, lay Lee's army.

The bugles and the drum corps of the respective armies were now

sounding reveille, and the troops were preparing for their early meal.

All knew we should have a battle today and a great one, for the enemy

had crossed the river in immense force, upon his pontoons during the

night. On the Confederate side all was ready, and the shock was awaited

with stubborn resolution. Last night we had spread our blankets upon the

bare floor in the parlor of Marye's house, and now our breakfast was

being prepared in its fireplace, and we were impatient to have it over.

After hastily dispatching this light meal of bacon and corn-bread, the

colonel, chief bugler, and I (the adjutant of the battalion) mounted our

horses and rode out to inspect our lines . . . .

At 12 o'clock the fog had cleared, and while we were sitting in

Marye's yard smoking our pipes, after a lunch of hard crackers, a

courier came to Colonel Walton, bearing a dispatch from General

Longstreet for General Cobb, but, for our information as well, to be

read and then given to him. It was as follows: "Should General Anderson,

on your left, be compelled to fall back to the second line of heights,

you must conform to his movements." Descending the hill into the sunken

road, I made my way through the troops, to a little house where General

Cobb had his headquarters, and handed him the dispatch. He read it

carefully, and said, "Well! if they wait for me to fall back, they will

wait a long time."

|

CONFEDERATE ARTILLERY IN ACTION ON MARYE'S HEIGHTS. (BL)

|

Hardly had he spoken, when a brisk skirmish fire was heard in front,

toward the town, and looking over the stone wall we saw our skirmishers

falling back, firing as they came: at the same time the head of a

Federal column was seen emerging from one of the streets of the town.

They came on at the double-quick, with loud cries of "Hi! Hi! Hi!" which

we could distinctly hear. Their arms were carried at "right shoulder

shift," and their colors were aslant the shoulders of the

color-sergeants. They crossed the canal at the bridge, and getting

behind the bank to the low ground to deploy, were almost concealed from

our sight. It was 12:30 p.m., and it was evident that we were now going

to have it hot and heavy.

How beautifully they came on! Their bright bayonets glistening

in the sunlight made the line look like a huge serpent of

blue and steel.

|

The enemy, having deployed, now showed himself above the crest of the

ridge and advanced in columns of brigades, and at once our guns began

their deadly work with shell and solid shot. How beautifully they came

on! Their bright bayonets glistening in the sunlight made the line look

like a huge serpent of blue and steel. The very force of their onset

leveled the broad fences bounding the small fields and gardens that

interspersed the plain. We could see our shells bursting in their ranks,

making great gaps; but on they came, as though they would go straight

through and over us. Now we gave them canister and that staggered them.

A few more paces onward and the Georgians in the road below us rose

up, and, glancing an instant along their rifle barrels, let loose a

storm of lead into the faces of the advance brigade. This was too much;

the column hesitated, and then, turning, took refuge behind the bank.

But another line appeared from behind the crest and advanced gallantly,

and again we opened our guns upon them, and through the smoke we could

discern the red breeches of the "Zouaves," and hammered away at them

especially. But this advance, like the preceding one, although passing

the point reached by the first column, and doing and daring all that

brave men could do, recoiled under our canister and the bullets of the

infantry in the road, and fell back in great confusion. Spotting the

fields in our front, we could detect little patches of blue—the

dead and wounded of the Federal infantry who had fallen

facing the very muzzles of our guns.

Cooke's brigade of Ransom's division was now placed in the sunken road

with Cobb's men. At 2 p.m. other columns of the enemy left the crest and

advanced to the attack; it appeared to us that there was no end of them.

On they came in beautiful array and seemingly more determined to hold

the plain than before; but our fire was murderous, and no troops on

earth could stand the feu d'enfer we were giving them. In the

forermost line we distinguished the green flag with the golden harp of

old Ireland, and we knew it to be Meagher's Irish brigade. The gunners

of the two rifle pieces . . . were directed to turn their guns against this

column; but the gallant enemy pushed on beyond all former charges, and

fought and left their dead within five and twenty paces of the sunken

road . . . .

The sharp-shooters having got range of our embrasures, we began to

suffer. Corporal Ruggles fell mortally wounded, and Perry, who seized

the rammer as it fell from Ruggles's hand, received a bullet in the arm.

Rodd was holding "vent," and away went his "crazy bone." In quick

succession Everett, Rossiter, and Kursheedt were wounded. Falconer in

passing in rear of the guns was struck behind the ear and fell dead. We

were now so short-handed that every one was in the work, officers

and men putting their shoulders to the

wheels and running up the guns after each recoil. The frozen ground had

given way and was all slush and mud. We were compelled to call upon the

infantry to help us at the guns. Eshleman crossed over from the right to

report his guns nearly out of ammunition; the other officers reported

the same. They were reduced to a few solid shot only. It was now 5

o'clock, p.m., and there was a lull in the storm. The enemy did not seem

inclined to renew his efforts, so our guns were withdrawn one by one,

and the batteries of Woolfolk and Moody were substituted . . . .

After withdrawing from the hill the command was placed in bivouac, and

the men threw themselves upon the ground to take a much-needed rest. We

had been under the hottest fire men ever experienced for four hours and

a half, and our loss had been three killed and twenty-four wounded . .

. . One gun was slightly disabled, and we had exhausted all of our

canister, shell and case shot, and nearly every solid shot in our

chests. At 5:30 another attack was made by the enemy, but it was easily

repulsed, and the battle of Fredericksburg was over, and Burnside was

baffled and defeated.

William Miller Owen,

"A Hot Day on Marye's Heights."

|

THE MARYE HOUSE ("BROMPTON") (USAMHI)

|

|

|

THE ATTACK ON MARYE'S HEIGHTS: A UNION PERSPECTIVE

Next morning, December 13th, the city was enveloped in a heavy fog,

which did not lift, if my recollection is clear, until ten o'clock or

later. As far as we could see in either direction stood a continuous

line of soldiers in readiness to start to the field of action. Mounted

officers and orderlies were continually passing back and forth along the

lines, while some of the regimental officers and privates, tired of

standing in the ranks, dropped out and sought a seat upon the curb or a

near-by door step. Among those who had taken a resting place was a

surgeon, upon whose face I noticed was depicted an intense feeling of

sadness. Perhaps he could not help it, for we all knew that some of us

would soon be badly wounded if not instantly killed. Yet this solemn

fact did not make all men gloomy. The most lively fellows mimicked the

whizzing noise of an occasional round shot or shell in its arched flight

high over the housetops, or cracked jokes with their comrades. . . .

Presently is heard the command, "Attention!". Every lounger springs

to his place. We are ordered to prime. Every musket is raised and every

man caps his piece. Our Colonel made some remarks, telling us to shoot

low and try to wound a man in preference to killing him. Noticing a red

colored scarf about my neck, he ordered me to take it off, saying it

would make a good target for the enemy. The scarf disappeared. Suspense

is intense. Finally, the long-expected, much-dreaded command, "Forward!"

is passed from officer to officer standing at the head of their

Companies. With an ominous silence akin to a funeral procession, General

Kimball began the perilous march down Caroline street. Reaching what I

will call Railroad avenue, the column filed to the right and out that

thoroughfare to begin the attack. I think I am telling the plain truth

when I say that during that short march many of those men silently

offered up to the Almighty their last prayer on earth. Our regiment was

about to receive its first baptism of fire, and every one knew it.

. . . Shells and solid shot from the enemy's heavy guns now came

crashing through brick walls and pounded in the street around about us.

The first wounded man I saw was hurrying down the sidewalk with one hand

pressed against a wound in his breast, inquiring for a hospital.

At the edge of the town we passed General Kimball facing us, in his

saddle, who addressed his men in these words, which I never forgot:

"Cheer up, my hearties! cheer up! This is something we

must all get used to. Remember, this brigade has never been whipped, and

don't let it be whipped today."

|

"Cheer up, my hearties! cheer up! This is something we must all get used

to. Remember, this brigade has never been whipped, and don't let it be

whipped today."

No wild hurrah went up in response. Every face wore an expression of

seriousness and dread . . . .

. . . A few steps further and we are out of the town, in the open

fields, in full view of the enemy. While the brigade is coming into

position, at double-quick, to assault the Confederate fortifications

around Marye's Heights, the artillerymen on the summit are turning their

guns upon us, and with effect. To facilitate our

progress in the charge, haversacks and blankets are now thrown away.

The company commanders shout sharply to their men to keep the regiments

in line as they advance to the attack. Screeching like demons in the

air, solid shot, shrapnel and shells from the batteries on the hills

strike the ground in front of us, behind us, and cut gaps in the ranks.

See there! A field officer has been struck by one of the missiles and a

couple of men who have raised him to his feet are calling loudly for

more help to get him off the field. As the line advances up the slope,

men wounded and dead drop from the ranks.

It is not every man that can face danger like this. I saw a few so

overcome by fear that they fell prostrate upon the ground as if dead. I

have seen men drop upon their knees and pray loudly for deliverance,

when courage and bravery, not supplication, was the duty of the

moment.

Hark! There's one of my comrades, Johnny Brayerton, praying, too,

perhaps for the first time in his life. It was a short one:

"Oh, Lord, dear, good Lord!" he cried.

But Johnny at that trying moment was as brave as he was devout, and kept

his place in the front rank. Not a gun was fired . . . until the brigade

reached the crest of the hill, when, like a burst of thunder, the roar

of musketry became almost deafening. It seemed to me every soldier,

after firing his piece, had thrown himself flat upon the ground to avoid

the enemy's bullets, and I did not see how I could possibly load and

fire by lying down in that crouching column of men. To stand up boldly

along that firing line—the dead line—was almost certain death,

so I ran to a blacksmith shop some distance to my right, where, with a

number of other soldiers who had taken refuge there, we banged away at

the rebels; but they were so securely and safely entrenched behind a

great stone wall, that I believe every man in the

firing line felt that there was not hope of a victory . . . .

|

THE GROUND BETWEEN FREDERICKSBURG AND MARYE'S HEIGHTS. (BL)

|

The little frame building from which we were firing was by no means

bullet-proof, yet we felt much safer there than standing out in full

view of the enemy. Down goes one of our party, shot through the

head.

I know not for what reason, but I stopped firing a few moments, and

stood over the lifeless form of the unknown soldier with a sort of

fascination, wondering who he could be; wondering what mother's boy had

been added to the roll of the dead . . . .

"There they come!" some one shouted, and looking back toward the

city, we saw another long line of reinforcements charging up the slope.

Lustily they were cheered as they advanced, and I noticed a wounded man

sitting upon the ground waving his cap and cheering with the rest. Until

nightfall, brigade after brigade charged across that field of death, to

the dead-line, only to suffer disaster and defeat.

I see a regiment charging up the slope towards the stone wall

opposite the Stephens' house. A large white dog is capering and leaping

ahead of the column. My eyes follow another brigade advancing across the

plain. They are veterans. The line keeps well dressed, but the men are

bending as low as they can travel, and the color-bearers trailing their

flags on the ground. Those heroic men are trying to avoid the

Confederate bullets, but many in the ranks never took part in another

fight. Here comes a regiment charging right towards us, advancing as

orderly as if on dress parade. The cool conduct of their Colonel

attracted the attention of a few, and some cried out:

"That's the way for a Colonel to bring in his men."

Some of the boys were jolly and laughing when they passed us, in

close column, by the blacksmith shop, out of sight. See! some of them

are already returning—I mean those that are wounded—to secure

shelter along with us in front of the building. Two stalwart fellows

came around the corner, dragging their dying Colonel riddled with

bullets. That regiment must have been literally cut to pieces . . .

.

A bullet crashed through the shop, throwing a splinter into the face

of a man standing near. He cursed in hot anger and left the spot. From

the blacksmith shop I hurriedly returned along the firing line to the

red brick house, near which we opened fire in the assault . . . .

General Kimball's brigade held its position at the firing-line until

relieved, but even then the men could not safely retire. The only

alternative was to lie at full length upon the ground, skulk into or

behind neighboring buildings, or, at much greater risk of being shot

down, withdraw to the rear. While at the brick house, looking around

about me upon the awful scene of carnage, a bullet grazed my head. I

watched a brigade charge up the slope, close to our left, but the brave

men, unable to withstand the withering fire, soon fell back in disorder,

followed by soldiers who had been at the dead-line since the first

attack by Kimball's men. With a number of others, in the mixed throng

collected in front of the brick building, the writer withdrew from the

field. All the way down the slope to the edge of the town I saw my

fellow-soldiers dropping on every side, in their effort to get out of

the reach of the murderous fire from the Confederate infantry securely

entrenched behind the long stone wall and the batteries on the heights.

I saw a shell explode, close to the heels of a large man fleeing for his

life. He was blown clear from the ground, falling in a heap, frightfully

mangled. A little further on, another unfortunate fellow was lying on

the ground, in a violent death struggle. At the edge of the town, two

men were helping off the field a badly-wounded comrade, who was cursing

in a frenzy of anger and vowing vengeance upon the rebels. A couple of

stretcher carriers were carrying to the hospital a man with both legs

shot away. It was a sickening sight. Scenes such as I have described

made a lasting impression upon my memory.

Benjamin Borton,

"On the Parallels"

|

French's third brigade stormed over the rise a few minutes later, but

the halt to maintain parade-ground intervals broke the momentum of those

three regiments as well, and they finally plodded forward and shouldered

into line with their predecessors. They knelt or lay in the muddy swale

or bid behind the cluster of buildings in the fork of Hanover Street and

the Telegraph Road, shooting ineffectually at the heights above them.

Most of their rounds scattered into the embankment behind the Southern

riflemen, whose eyes and muzzles alone peered over the stone wall,

presenting a long, bright blade of fire that flayed the fat Federal

line. French's assault was over.

|

NATHAN KIMBALL'S BRIGADE WAS THE FIRST

TO ATTACK MARYE'S HEIGHTS. DISREGARDING THE FIRE OF CONFEDERATE GUNS,

KIMBALL'S MEN ADVANCED STEADILY TO WITHIN 60 YARDS OF THE STONE WALL.

THEY COULD GO NO FURTHER. (ANNE S. K. BROWN MILITARY COLLECTION, BROWN

UNIVERSITY)

|

|

|