|

BURNSIDE'S PLAN APPROVED, THEN FOILED

When he returned to his comfortable office in Washington, Halleck did

present Burnside's plan to Lincoln, who approved it

with the caveat that Burnside would have to act quickly. Halleck did not

attend so conscientiously to the pontoon question, however, and Sumner's

troops stepped off toward Fredericksburg before the pontoons even

started down from the upper Potomac. The first Federal infantry tramped

into Falmouth on the evening of November 17, and General Sumner asked

permission to cross some cavalry over a precarious ford to take

Fredericksburg, which was lightly defended. Burnside declined, lest the

horse soldiers find themselves trapped by rising water, and indeed rain

began to fall as though on cue. Burnside ached to cross while the city

was lightly defended, too, and when he rode into Falmouth on November 19

he wrote Halleck that he would do so as soon as the pontoons

arrived.

|

ALFRED WAUD SKETCHED THIS VIEW OF FREDERICKSBURG AS SEEN FROM FALMOUTH

JUST DAYS BEFORE THE BATTLE. (LC)

|

The first of the pontoons did not even leave Washington until that day,

and (because General Halleck had not apprised his engineer officer how

badly Burnside needed them) they rolled out on ponderous wagons. The

same storm that lifted the Rappahannock turned Virginia roads into muck,

and the pontoon train slowed to a crawl, stopping altogether at the washed-out

bridges over the Occoquan River. Only then did the engineer in

charge of the work divert some of the pontoons to a steamboat, which

delivered them at Belle Plains landing on November 22. Even these few,

enough for a full bridge or two, did not reach the army until November

24. The bulk of the pontoon wagons finally pulled up at Falmouth, ready

for use, on the afternoon of November 27—some ten days after

Burnside expected them.

By then it was too late for the Army of the Potomac to waltz

unchallenged into Fredericksburg. As early as November 15 Lee suspected

that Burnside might be headed for Fredericksburg, and he sent a regiment

of infantry and a battery of artillery to bolster the city's garrison.

Lee thought, incorrectly, that Burnside favored shipping his army back to

the James River. Consequently the Confederate commander supposed for a

time that the Fredericksburg movement merely served as the screen for a

general withdrawal back to the wharves at Alexandria. By the morning of

November 18, however, he started two divisions of Longstreet's corps on

the road to Fredericksburg, following it with the balance November 19.

The next day Lee himself telegraphed Jefferson Davis from Fredericksburg

to say he believed the Yankees were concentrating for a strike at that

place. The last of Longstreet's corps filed into the city on November

23, and on that day Lee directed Stonewall Jackson to bring his corps

east of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

|

A TRAIN OF PONTOONS LIKE THOSE USED BY BURNSIDE TO SPAN THE RAPPAHANNOCK

RIVER. THE TARDY ARRIVAL OF THE PONTOONS UPSET BURNSIDE'S PLANS FOR AN

EASY CROSSING AND ULTIMATELY DOOMED HIS CAMPAIGN TO FAILURE (NA)

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

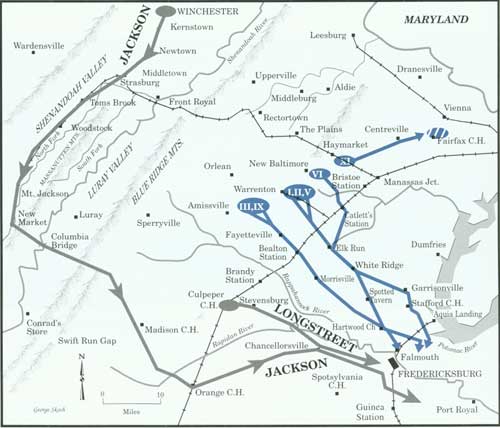

THE ARMIES MOVE TO FREDERICKSBURG, NOVEMBER 15—DECEMBER 4

When the Fredericksburg Campaign opens, the Army of the Potomac is

centered near Warrenton Junction, north of the Rappahannock River. On

November 15th, Sumner's grand division marches toward Fredericksburg,

followed by Franklin and Hooker. Burnside plans to cross the

Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg, but is prevented from doing so by

the tardy arrival of his pontoon train. By the time the pontoons arrive,

Longstreet's Confederate corps occupies the heights behind the town. In

early December, Jackson's corps arrives from the Shenandoah Valley and

takes position south of Fredericksburg, toward Port Royal. With

Jackson's arrival, the Confederate army is reunited and ready for

battle.

|

|

AT THE TIME OF THE WAR, FREDERICKSBURG WAS A COMMERCIAL TOWN OF 5,000

INHABITANTS. WHEN CONFEDERATE FORCES ABANDONED THE TOWN IN APRIL, 1862,

THEY DESTROYED THE BRIDGES ACROSS THE RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER.

|

In one of his messages to Jackson, Lee intimated that he did not intend

to resist Burnside on the Rappahannock. The geography favored the

Federals there, he felt, because of the heights that towered on

Burnside's bank of the river. Lee preferred the North Anna River, where

the high ground would have loomed on his side, but he probably guessed

that his president would frown on retreating so much nearer to Richmond.

Employing his renowned tact, he therefore tried to persuade Davis of the

wisdom of a Fabian withdrawal, destroying the railroad and otherwise

impeding Burnside's progress until winter; he posed the notion in such a

fashion that Davis might feel it had been his own idea. Lee's diplomacy

did not succeed, but neither did the Yankees offer to cross the

Rappahannock immediately, so Longstreet's corps remained in camp on a

long ridge a mile southwest of the river.

|

|