|

HANCOCK'S ATTACK, AND HOWARD'S

Next came Winfield Scott Hancock, with one of the best divisions in the

Army of the Potomac. Hancock likewise threw his five thousand men at the

wall in three waves. His first brigade rolled over French's stalled

line, surging toward the still blue bodies that marked the limit of

Kimball's farthest advance, sixty yards from the wall. There it stopped,

though, and began creeping slowly backward as men shrank involuntarily

from the withering fire. Behind them came the Irish Brigade,

some twelve hundred strong, but neither could these veterans close the

deadly gap between the lines; by day's end nearly five hundred of them

had been shot.

|

UNION TROOPS ATTACKING MARYE'S HEIGHTS,

AS SEEN BY ARTIST ALFRED WAUD FROM A STEEPLE IN TOWN.

(LC)

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

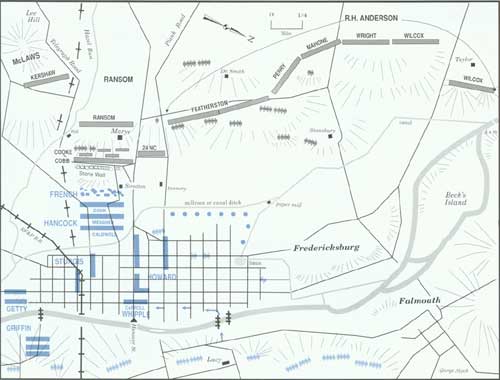

HANCOCK GOES TO FRENCH'S SUPPORT: DECEMBER 13, 1 P.M.—2 P.M.

As French's attack falters, Couch sends Hancock's division forward to

support it, but Hancock is likewise repulsed. Howard's division then

files toward the front, hoping to outflank the Confederate defenders

behind the stone wall while Sturgis advances to shore up Couch's

endangered left flank. Meanwhile, part of Cooke's brigade joins Cobb's

men in the Sunken Road.

|

Hancock's last brigade burst through the gaggle of survivors, losing

much of its cohesion in the process, and sprinted forward past the

earlier casualties. Parts of these six regiments came within shouting

distance of the Telegraph Road, and individuals ventured closer still,

but not in sufficient numbers to threaten the Confederate infantry. A

deflected piece of shell bowled over the colonel of the 5th New

Hampshire just beyond the millrace bluff. His men finished the assault

under their major, who lifted his sword over his head and disappeared

into the smoke before the stone wall, followed by half a dozen of his

most intrepid soldiers. None of them came back, and that major may have

been the officer whose body fell only thirty paces from the wall. "On

all sides," wrote the wounded New Hampshire colonel, "men fell like

grass before the scythe." Southern fire leveled 60 percent of his

regiment.

|

DARIUS COUCH (BL)

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

STURGIS AND HOWARD ATTACK: DECEMBER 13, 2 P. M.—3 P.M.

Sturgis advances in an effort to shore up Couch's left flank, while

Howard attacks with two brigades astride Hanover Street. Ransom's

brigade joins the fighting on the heights, while Kershaw's remaining

regiments move down the Telegraph Road toward the front.

|

From the courthouse cupola, Darius Couch watched the repulse of his

first two divisions. As each brigade resolutely advanced into the face

of Southern rifles, he wrote, it would "melt like snow coming down on

warm ground." He soon realized that the Confederate line could not be

broken at that point. Oliver O. Howard, the one-armed brigadier general

who commanded Couch's remaining division, stood with him in the cupola.

Just before one o'clock Couch ordered Howard to sidle farther to the

right and attack the stone wall at the northern end, where he might be

able to flank the riflemen hiding behind it. Simultaneously Couch sent

couriers up to Hancock and French with orders to storm the wall, but

those two appealed to Couch for reinforcements: between casualties and

the stragglers who drifted away from the front by scores, the firing

line was growing dangerously thin. Couch therefore canceled Howard's

earlier orders and instructed him to go to Hancock's aid. Howard threw

one brigade in behind Hancock, south of Hanover Street, and pushed

another into the empty ground north of Hanover Street. He kept his last

brigade just behind, on the outskirts of town.

|

THOMAS R. R. COBB (BL)

|

For all the frustration of the Federal generals, Robert F. Lee feared

that the mounting pressure in front of Marye's Heights might carry his

line, but Longstreet assured him he could hold the stone wall. Two

regiments of North Carolinians, exposed on the open hillside without

rifle pits, plunged down into the Sunken Road to support the Georgians,

whose General Cobb had fallen—within sight of the house where his

parents were married—with shrapnel in his leg. He bled to death

after being carried to the rear, but his men stood firm: during the

whole fight his brigade suffered fewer casualties than some of the

dozens of Union regiments that were hurled against the wall.

|

|