|

JULY 3, 3 P.M.—THE CHARGE

Longstreet, who doubted that the attack would succeed, reluctantly

ordered the assault column forward at about 3 P.M., and the nine

Confederate brigades stepped out, guiding on the clump of trees visible

on the ridge 1,400 yards ahead. Herb's division marched straight ahead;

Pickett's had to make successive shifts to the left to close ranks on

Heth's as it approached the Copse of Trees. The Confederate line was a

long one, measuring about a mile from left to right when the assault

began. The ground over which it charged was open but was crossed with

shallow' depressions into which the advancing formations would disappear

briefly from the view of the Union soldiers in their front.

Nevertheless, the Union batteries from Little Round Top to Cemetery Hill

fired on the Confederate lines as soon as they hove into view and

punched gaps in the advancing ranks. In fifteen minutes the attackers

reached the Emmitsburg Road, climbed its fences, and dressed their

lines. By this time the artillery pieces within 400 yards of the

assaulting Confederates were firing canister, and the Union infantry

blasted them with rifle fire. The Confederates closed the gaps created

by the Federal fire, Pickett's men siding to the left, Heth's to the

right, and the mile-long front shrank to a compact one of a half mile

from flank to flank.

|

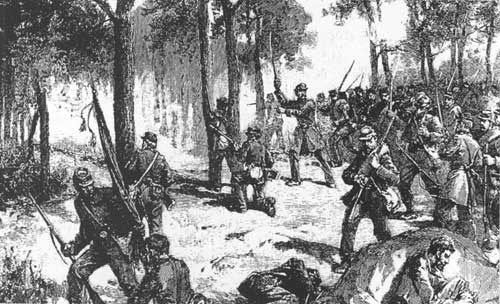

WOOD ENGRAVING OF STEUART'S BRIGADE RENEWING THE CONFEDERATE ATTACK ON

CULP'S HILL (BL)

|

|

THE HIGH-WATER MARK OF THE CONFEDERATE CAUSE WAS REACHED AT THE ANGLE AS

SOUTHERN TROOPS PENETRATED THE UNION LINES BEFORE BEING REPULSED. THIS

PAINTING BY PHILIPPOTEAUX IS PART OF THE GETTYSBURG CYCLORAMA (GNMP)

|

|

PICKETT'S CHARGE; A CONFEDERATE AND UNION PERSPECTIVE

The following account was written by captain Henry T. Owen, 18th

Virginia Infantry, Garnett's Brigade, Pickett's Division. It originally

appeared in the Philadelphia Weekly Press.

The command now came along the line, "Front, forward!" and the column

resumed its direction straight down upon the centre of the enemy's

position. The destruction of life in the ranks of that advancing host

was fearful beyond precedent, officers going down by dozens and the men

by scores and fifties.

We were now four hundred yards from the foot of Cemetery Hill, when

away off to the right, nearly half a mile, there appeared in the open

field a line of men at right angles with our own, a long, dark mass,

dressed in blue, and coming down at a "double-quick" upon the unprotected

right flank of Pickett's men, with their muskets "upon the right

shoulder shift," their battle flags dancing and fluttering in the breeze

created by their own rapid motion, and their burnished bayonets

glistening above their heads like forest twigs covered with sheets of

sparkling ice when shaken by a blast. The enemy were now seen

strengthening their lines where the blow was expected to strike by

hurrying up reserves from the right and left, the columns from opposite

directions passing each other double along our front like the fingers of

a man's two fingers locking together. The distance had again shortened

and officers in the enemy's

lines could be distinguished by their uniforms from the privates. Then

was heard that heavy thud of a muffled tread of armed men that roar and

rush of tramping feet as Armistead's column from the rear closed up

behind the front line and he (the last brigadier) took command, stepped

out in front with his hat uplifted on the point of his sword and led the

division, now four ranks deep, rapidly and grandly across that valley of

death, covered with clover as soft as a Turkish carpet.

There it was again! and again! A sound filling the air above, below,

around us, like the blast through the top of a dry cedar or the whirring

sound made by the sudden flight of a flock of quail. It was grape and

canister, and the column broke forward into a double quick and rushed

toward the stone wall where forty cannon were belching forth grape and

canister twice and thrice a minute. A hundred yards from the stone

wall the flanking party on the right, coming down on a heavy nun,

halted suddenly within fifty yards and poured a deadly storm of musket

balls into Pickett's men, double-quicking across their front, and, under

this terrible cross fire the men reeled and staggered between falling

comrades and the right came pressing down upon the centre, crowding the

companies into confusion. But all knew the purpose to carry the heights

in front, and the mingled mass, from fifteen to thirty feet deep, rushed

toward the stone wall, while a few hundred men, without orders, faced

to the right and fought the flanking party there, although fifty to one,

and for a time held them at bay. Muskets were seen crossed as some

fired to the right, and others to the front and the fighting was

terrific—far beyond all other experience even of Pickett's men, who

for once raised no cheer, while the welkin rang around them with the

"Union triple huzza." The old veterans saw the fearful odds against

them and other hosts gathering darker and deeper still.

The time was too precious, too serious for a cheer; they buckled

down to the heavy task in silence, and fought with a feeling like

despair. On swept the column over ground covered with dead and dying

men, where the earth seemed to be on fire, the smoke dense and

suffocating, the stun shut out, flames blazing on every side, friend

could hardly be distinguished from foe, but the division, in the shape

of an inverted V, with the point flattened, pushed forward, fighting,

falling and melting away, till half way up the hill they were met by a

powerful body of fresh troops, charging down upon them, and this remnant

of about a thousand men was hurled back-out into the clover field.

Brave Armistead was down among the enemy's guns, mortally wounded.

|

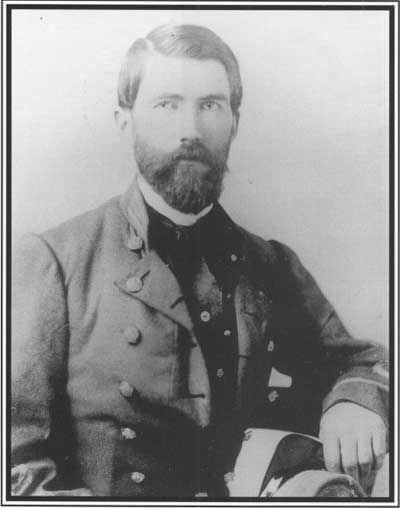

CAPTAIN HENRY THWEATT OWEN, COMPANY C, 18TH VIRGNIA INFANTRY (GNMP)

|

Near Gettysburg, July 6, 1863

My Dear Papa,

When our great victory

was just over the exultation of victory was so great that one didn't

think of our fearful losses, but now I can't help feeling a great

weight at my heart. Poor Henry Ropes was one of the dearest fiends I

ever had or expect to have. His loss is terrible. His men actually wept

when they showed me his body, even under the tremendous cannonade, a

time when most soldiers see their comrades dying around them with

indifference.

Indeed with only two officers besides myself remaining, I can't help

feeling a little spooney when I am thinking, & you know I am

not at all a lachrymose individual in general. However I think we can

run the machine. Our losses are of—13 officers, 3 killed, 7

wounded. Of 231 enlisted men, 30 killed, 84 wounded, 3 missing, total

117, with officers, aggregate 127.

The enemy, after a morning of quiet on our part of the line (a

little to the right of the left center) began the most terrific

cannonade, with a converging fire of 150 pieces, that I have ever heard

in my life & kept it up for 2 hours, almost entirely disabling our

batteries, killing & wounding over half the officers & men [of

the artillery] & silencing most of the guns. The thin line of our

division against which it was directed was very well shielded by a

little rut they lay in & in front of our brigade by a little pit,

just one foot deep & one foot high, thrown up hastily by one

shovel, but principally by the fact that it is very difficult to hit a

single line of troops, so that the enemy chiefly threw over us with the

intention of disabling the batteries & the reserves which they

supposed to be massed in the rear of the batteries, in the depression

of the hill.

The rebels thus left us entirely unsupported & advanced with

perfect confidence after ceasing their artillery—our artillery

being so knocked up that only one or two shots were fired into them,

which, however, were very well aimed, & we could see [the shots]

tumble over squads in the rebel lines. Had our batteries been intact,

the rebels would never have got up to our musketry, for they were

obliged to come out of the woods & advance from a half to 3/4 of a

mile over an open field & in plain sight. A magnificent sight it was

too. Two brigades in two lines, their skirmishers driving in ours.

The moment I saw them I knew we should give them Fredericksburg. So

did every body. We let the regiment in front of us get within 100 feet

of us, & then bowled them over like nine pins, picking out the

colors first. In two minutes there were only groups of two or three men

running round wildly, like chickens with their heads off. We were

cheering like mad, when Macy directed my attention to a spot 3 or 4 rods

on our right where there were no pits, only a rail fence, Baxter's

Pennsylvania men had most disgracefully broken, & the rebels were

within our line. The order was immediately given to fall back far enough

to form another line & prevent us [from] being flanked. Without

however waiting for that, the danger was so imminent that I had rushed

my company immediately up to the gap, & the regiment & the rest

of the brigade, being there some before & the rest as quick as they

could. The rail fence checked the main advance of the enemy & they

stood, both sides pegging away into each other.

The rows of dead after the battle I found to be within 15 and 20 feet

apart, as near hand to hand fighting as I ever care to see. The rebels

behaved with as much pluck as any men in the world could; they stood

there, against the fence, until they were nearly all shot down. The

rebels' batteries, seeing how the thing was going, pitched shell into us

all the time, with great disregard of their own friends who were so

disagreeably near us.

The field was mostly open where we were with scarcely a perceptible

rise, commanded by the rebel side: on the center a little wooded, still

better commanded by the rebel side; on the right, I am told, wooded

& rocky, both parties contending for the slopes towards us . . . .

Moreover, our line of retreat was so narrow that it was easy, if our

left was turned, to cut us off from it. Had the rebels driven in our

left (they twice tried it & I have told you how near they came to

it) it would have been all up with us.

The advantages of our position were that the comdg. general could

over look almost the whole line, a rare thing in this country, &

that moving on the chord of the circle while the enemy moved on the arc,

we could reinforce any part of the line from any other part much quicker

than they could, an advantage which Meade availed himself of admirably

in the first day's rebel attack, but which their shell fire prevented

him from doing in the second day's.

My love of course to all the family including George (Perry) and Mary

Welch.

Your aff. son,

H. L. Abbott

|

MAJOR HENRY LIVERMORE ABBOTT, 20TH MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY (LETTER

REPRINTED FROM FALLEN LEAVES: THE CIVIL WAR LETTERS OF MAJOR HENRY

LIVERMORE ABBOTT, COURTESY OF KENT STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS)

|

|

As the Confederates neared the Union position, Brig. Gen. James L.

Kemper, whose brigade was on the right, stood in his stirrups, pointed

left with his sword, and shouted, "There are the guns, boys, go for

them!" With that and their closing left to fill gaps, Kemper's men

shifted across the front of Doubleday's division into Gibbon's sector.

When the Virginians sided from his front, Brig. Gen. George J. Stannard

ordered two regiments from his Vermont brigade to wheel right from its

position, about 500 yards south of the Copse of Trees, and march in

front of the Union line against the assault column's right. At the same

time, Union batteries on Cemetery Hill and infantrymen that had been

posted near the Emmitsburg Road beyond the column's left fired into the

Confederate flank and caused Heth's left brigade to head to the rear.

And so, as the assault column neared its objective, it took fire from

three sides. Three brigade commanders fell—Kemper and Col. Birkett

D. Fry with wounds, Brig. Gen. Robert B. Garnett killed. Division

commanders fared little better. Although Pickett emerged unscathed,

Pettigrew sustained a wound in the hand and Maj. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble,

commanding Pender's two brigades, lost a leg. The loss of Confederate

leaders in all echelons in the attack force would prove disastrous.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL LEWIS ARMISTEAD LEADS CONDERATE SOLDIERS OVER

"THE ANGLE" (PAINTING BY DON TROIANI, PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF

HISTORICAL ART PRINTS, SOUTHBURY, CT.)

|

The attacking lines converged on the center, senior officers fell,

formations mixed, and the attackers lost cohesion and firepower. Yet

several thousand of them had reached the slope of the ridge and, in the

words of a Confederate officer, became a "mingled mass, from fifteen to

thirty deep." With leaders falling and formations melding, the

Confederates lost momentum and did not push the attack home. Instead,

they became a target that Union soldiers could not miss. Men of

Hancock's Second Corps, who had felt the Rebels' wrath when they

attacked Marye's Heights the previous December, took their revenge and

shouted "Fredericksburg" as they fired. Lt.

Alonzo H. Cushing, whose U.S. battery had

held the Angle and who had already suffered a serious wound, fell dead

when struck in the mouth by a bullet as he shouted for his guns to

fire.

It must have been about this time and amid all of this chaos that a

soldier in Armistead's brigade said, "What a sublime sight!" and then

looked at his watch and said that they had been "just nineteen minutes

coming." These were the last words he spoke. Not far away the right of

Pettigrew's line struck the Angle, and as it did a lieutenant from

Armistead's brigade walked to a Tennessee captain in Archer's brigade,

shook his hand, and said, "Virginia and Tennessee will stand together on

these works today!" Most of Heth's men who had come this far pressed

toward the wall north from the Angle and about 75 yards in its rear.

Brig. Gen. Alexander Hays's division of the Second Corps held this

sector. It was a strong position that the Confederates could not

reach.

Gen. Lewis A. Armistead held his hat aloft on his sword

and shouted, "Come on, boys, give them the cold steel!

Who will follow me?"

|

The Union position south from the Angle was more accessible and

vulnerable. Maj. Gen John Gibbon's division, the brigades of Alexander

Webb, Norman J. Hall, and William Harrow, held this portion of the

Union line, and Doubleday's division was on their left. Webb's brigade

and Cushing's guns manned the Angle. Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Armistead,

commander of Pickett's support brigade, pushed his way to the front of

the mass in front of the Angle, his hat held aloft on his sword, and

shouted, "Come on, boys, give them the cold steel! Who will follow me?"

Some men surged after him over the wall and into the area held by

Cushing's wrecked battery. Others pushed by the 69th Pennsylvania

Regiment into the Copse of Trees and against Capt. Andrew Cowan's New

York battery, which had taken position where

the Rhode Island battery had been south of the Copse of Trees. Cowan

shouted, "Double canister, at ten paces." Five of his guns belched their

cans of balls and swept the threat away.

As Cowan's guns blew away the Confederates in their front, so the

brigades of Hall and Harrow, which also were posted just south of the

copse, drove their attackers back. This done, they turned right toward

the penetration and helped Webb's brigade seal off and destroy the

bulge. (In later years men would call the area reached by the

Confederate surge "The High-Water Mark of the Confederacy," mark it with

a special monument, and protect the taller trees of the copse with an

iron fence.)

Thus it was that men of the nine shattered brigades that had set

off less than an hour before under the command of Pickett, Pettigrew,

and Trimble returned as individuals to Seminary Ridge. Sadly enough,

it was at this time that Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox led his brigade

and the Florida brigade of Anderson's division against the Union sector

guarded by McGilvery's guns and the left of the Vermont brigade. They

had been ordered forward to guard Pickett's right, but by the time they

approached the Union line Pickett's right had been destroyed. A

"terrible fire of artillery" seared their lines, and the Vermonters

mowed against their left and rear. When he saw that his men were hurt "a

useless sacrifice," Wilcox ordered them back. So ended the grand

Confederate charge.

Nearly 5,600, over 50 percent, of the Confederates who had charged

became casualties; Union losses may have numbered about 1,500. General

Lee rode into the field of the charge to rally and console its

survivors. On meeting Lt. Col. Samuel G.

Shepard, commander of the remnant of Archer's brigade, he said,

"Colonel, rally your men to protect our artillery. The fault is mine,

but it will be right in the end."

|

|