|

THIS CONSECRATED GROUND

Nearly 20,000 wounded and dying soldiers occupied its public

buildings and many of its houses.

|

After the battle, the Gettysburg area was a tragic place. Dead

horses, the bodies of soldiers, and the debris of battle littered its

trampled fields. Many of its buildings were damaged, its fences gone,

and its air polluted with the odor of rotting flesh. Nearly 20,000

wounded and dying soldiers occupied its public buildings and many of its

houses; Union and Confederate hospitals clustered at many of its farms.

Medical authorities transferred the wounded to general hospitals in

nearby cities as soon as practicable. Dr. Henry Janes, the surgeon in

charge of medical activities at Gettysburg, established a general

hospital along the York Pike a mile east of the town in mid-July. The

last of the wounded did not leave Gettysburg until November 23—over

four months after the battle.

Although the armies had hurried many of their dead before marching

away, many bodies remained above ground, and heavy rains that began on

July 4 washed open the shallow graves of others. Many Union dead were

embalmed and sent to their homes, and survivors of a few purchased lots

for them in Evergreen Cemetery. Confederate dead were buried as

individuals or in mass graves near the places of their deaths. After the

war, the bodies of some of the known Confederate dead were exhumed and

taken to home cemeteries.

Most, however, remained at Gettysburg until the early 1870s, when

southern Ladies Memorial Associations had the remains of 3,320

Confederate soldiers exhumed and taken south. They reburied 2,935 of

them in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond. Virginia.

Northern states with units in the battle sent agents to Gettysburg to

look after their dead and wounded soldiers. Governor Andrew G. Curtin of

Pennsylvania visited Gettysburg soon after the battle, saw its problems,

and named David Wills, a Gettysburg attorney, as Pennsylvania's agent.

Soon Wills and other agents decided that a cemetery should be

established for the Union dead. With Curtin's permission, Wills soon

purchased seventeen acres on the northwest slope of Cemetery Hill for a

cemetery and hired the noted landscape architect William Saunders to

create a cemetery plan.

|

THE CIVILIAN COST OF BATTLE

The path of the battle was like a violent storm that left a wake

of destruction wherever it traveled. The farmers, upon whose land the

majority of the battle took place, suffered severely. In some cases,

nearly everything was lost. This photo of the Catherine Trostle farm was

taken on July 6, four days after the fighting had raged around her

farm. Some sense of what the battle cost her can be realized in the

claims shown below that she filed for damages with both the state and

federal government. There were dozens of other farmers whose circumstances

mirrored those of Catherine Trostle. Few of them, including Mrs.

Trostle, were ever compensated for their losses.

To the Board of Commissioners appointed to assess the damages

occasioned by the rebel invasions of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

under the act approved April 9, 1868. The petition of Catherine Trostle

on behalf of Abram Trostle, respectfully sheweth that he was a resident

of Cumberland township, Adams County, Pennsylvania, in the year 1863;

that on or about the 1st to 4th of July, 1863, he sustained loss and

damage to his property situate and being in Cumberland township, in said

County of Adams, by the causes referred to in said Act of Assembly . . .

. as follows, viz:

| 27 acres wheat destroyed, worth | $600.00 |

| 9 acres Corn | 360.00 |

| 8 acres Oats | 80.00 |

| 4 acres Barley | 50.00 |

| 1 acre Flax | 15.00 |

| 1 acre Potatoes | 50.00 |

| 32 acres Grass | 650.00 |

| 20 tons of Hay out of the barn | 300.00 |

| 6400 Rails destroyed | 512.00 |

| House and Barn injured by shells, and used for hospital | 200.00 |

| 3 Cows killed in the battle, @40.00 | 120.00 |

| Heifers @ $20 | 40.00 |

| 1 Bull, | 20.00 |

| 1 Large Hog | 15.00 |

| 1 Sheep. | 5.00 |

| 50 Chickens | 12.50 |

| 2 Hives of Bees | 14.00 |

| 1 Saddle & 2 bridles | 20.00 |

| 2 Barrels of Ham & Shoulders say 200 lbs. @ 20cent | 40.00 |

| Beds and Bedding | 50.00 |

| Clothes of family | 20.00 |

| Household and Kitchen goods and Queensware | 15.00 |

|

That her husband, Abraham Trostle, has become insane, and is now in

the Lunatic Asylum, that their farm was near Round Top, and was fought

over two days, and the crops and fences were totally destroyed. The

fences were burned.

The cows and other stock and cattle, and fowls, were partly killed

on the field, and some driven away, the farm being between the two

armies, in part was fought over several times; that the family was

driven from the house, which was taken possession of by the soldiers,

and nursed for wounded men, and it was also struck by shells and

balls, and much injured. There were 16 dead horses left close by the

door and probably 100 on the farm. She believes the property was damaged

and lost to the amount claimed.

That her husband had 15 barrels of flour in Myers Mill which was

taken by the rebels, and was worth $120.00.

|

VIEW OF TROSTLE FARM WITH DEAD HORSES FROM 9TH MASSACHUSETTS BATTERY (GNMP)

|

|

The interment of Union dead in this, the Soldiers' National Cemetery,

began almost at once, and by the spring of 1864 3,500 bodies were buried

there. They interred the battle dead known by name or state in state

plots and the 979 unidentified dead in plots for the unknown at each end

of the arc of graves. Now 3,706 Civil War dead are buried in the

cemetery along with approximately that many dead of later wars.

Wills invited the Honorable Edward Everett to deliver the main

address at the cemetery's dedication on November 19, 1863. Everett had

been president of Harvard, governor of Massachusetts, a senator, and a

secretary of state and was one of the leading orators of his time. The

commissioners invited President Lincoln to the ceremony, and after the

president accepted the invitation, asked him to participate in the

program.

|

CHRISTIAN COMMISSION TENTS AT UNION 2ND CORPS HOSPITAL (LC)

|

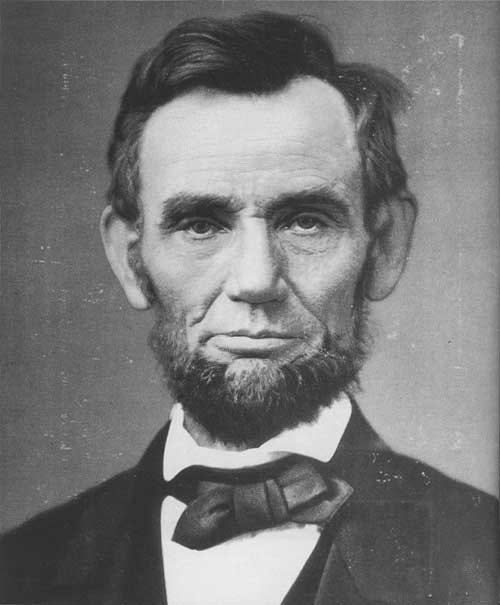

President Lincoln took this invitation seriously, and before leaving

Washington he prepared a brief but thoughtful address. He made revisions

to his original draft before the dedication while a guest in the Wills

home on the square in Gettysburg.

The dedication ceremonies began at noon on November 19, 1863. The

program included music by the Marine band, prayers, and hymns. Everett

gave an address that reviewed the course of the battle and lasted

nearly two hours. The president's remarks required only a few minutes,

but they have become immortal.

There are five autograph copies of President Lincoln's Gettysburg

Address. The first two drafts (Lincoln's address on the 19th probably

followed the text of the second) are in the custody of the Library of

Congress, but one is on display at Gettysburg National Military Park

part of each year. The third copy, which the president wrote to be sold

at the Sanitary Commission Fair in New York City in 1864, is in the

Illinois State Library. The fourth copy was written to be published in a

book, Autograph Leaves of Our Country's Authors, which was to be

sold at the Soldiers' and Sailors' Fair in Baltimore in 1864, but could

not be used for this purpose because Lincoln had copied it on both sides

of the paper. Lincoln gave this copy to George Bancroft, the historian,

and now this "Bancroft Copy" is in the Cornell University Library. The

copy written to replace it, which was owned by Col. Alexander Bliss,

publisher of Autumn Leaves and called the "Bliss Copy," is in the

White House.

|

GETTYSBURG: A WOMAN'S STORY

Cornelia Hancock was a 23-year-old woman from Hancock's Bridge,

New Jersey, who sought to aid the war effort in some way. The battle at

Gettysburg offered her the opportunity, and she made her way to the

field, arriving on July 7th. She described the scene she encountered at

the Union Second Corps hospital, where she served as a volunteer

nurse.

Learning that the wounded of the Third Division of the Second Corps,

including the 12th Regiment of New Jersey, were in a Field Hospital

about five miles outside of Gettysburg, we determined to go there early

the next morning, expecting to find some familiar faces among the

regiments of my native state. As we drew near our destination we began

to realize that war has other horrors than the sufferings of the wounded

or the desolation of the bereft. A sickening, overpowering, awful stench

announced the presence of the unburied dead, on which the July sun was

mercilessly shining, and at every step the air grew heavier and fouler,

until it seemed to possess a palpable horrible density that could be

seen and felt and cut with a knife. Not the presence of the dead bodies

themselves, swollen and disfigured as they were, and lying in heaps on

every side, was as awful to the spectator as that deadly, nauseating

atmosphere which robbed the battlefield of its glory, the survivors of

their victory, and the wounded of what little chance of life was left to

them.

As we made our way to a little woods in which we were told was the

Field Hospital we were seeking, the first sight that met our eyes was a

collection of semi-conscious but still living human forms, all of whom

had been shot through the head, and were considered hopeless. They were

laid there to die and I hoped that they were indeed too near death to

have consciousness. Yet many a groan came from them, and their limbs

tossed and twitched. The few surgeons who were left in charge of the

battlefield after the Union army had started in pursuit of Lee had begun

their paralyzing task by sorting the dead from the dying, and the dying

from those whose lives might be saved; hence the groups of prostrate,

bleeding men laid together according to their wounds.

|

CORNELIA HANCOCK (PHOTOGRAPH AND LETTER REPRINTED FROM "WOMEN AT

GETTYSBURG 1863," BY E. F. CONKLIN, THOMAS PUBLICATIONS, GETTYSBURG,

PA.)

|

There was hardly a tent to be seen. Earth was the only available bed

during those first hours after the battle. A long table stood in this

woods and around it gathered a number of surgeons and attendants. This

was the operating table, and for seven days it literally ran blood. A

wagon stood near rapidly filling with amputated legs and arms; when

wholly filled, this gruesome spectacle withdrew from sight and returned

as soon as possible for another load. So appalling was the number of the

wounded as yet unsuccored, so helpless seemed the few who were

battling against tremendous odds to save life, and so overwhelming was

the demand for any kind of aid that could be given quickly, that one's

senses were benumbed by the awful responsibility that fell to the

living. Action of a kind hitherto unknown and unheard of was needed here

and existed here only.

From the pallid countenances of the sufferers, their inarticulate

cries, and the many evidences of physical exhaustion which were common

to all of them, it was swiftly borne in upon us that nourishment was one

of the pressing needs of the moment and that here we might be of

service.

Our party separated quickly, each intent on carrying out her own

scheme of usefulness. No one paid the slightest attention to us,

unusual as was the presence of half a dozen women on such a field; nor

did anyone have time to give us orders or to answer questions. Wagons of

bread and provisions were arriving and I helped myself to their stores.

I sat down with a loaf in one hand and a jar of jelly in the other:

it was not hospital diet but it was food, and a dozen poor fellows lying

near me turned their eyes in piteous entreaty, anxiously watching my

efforts to arrange a meal.

... It seemed as if there was no more serious problem under Heaven

than the task of dividing that too well-baked loaf into portions that

could be swallowed by weak and dying men. I succeeded, however, in

breaking it into small pieces, and spreading jelly over each with a

stick. I had the joy of seeing every morsel swallowed greedily by those

whom I had prayed day and night I might be permitted to serve. An hour

or so later, in another wagon, I found boxes of condensed milk and

bottles of whiskey and brandy. I need not say that every hour brought an

improvement in the situation, that trains from the North came pouring

into Gettysburg laden with doctors, nurses, hospital supplies, tents,

and all kinds of food and utensils: but that first day of my arrival,

the sixth of July, and the third day after the battle, was a time that

taxed the ingenuity and fortitude of the living as sorely as if we had

been a party of shipwrecked mariners thrown upon a desert island.

|

The Soldiers' National Cemetery was incorporated by the Commonwealth

of Pennsylvania in March 1864 but was turned over to the United States

government as a national cemetery on May 1, 1872. Apart from its

headstones and memorials to units that were posted in the cemetery area

during the battle, the national cemetery contains four memorials of

note. The principal memorial, the Soldiers National Monument,

was ordered by the cemetery's Board of Commissioners for placement at

the center of the arc of graves. James G. Batterson provided its design,

and it was dedicated on July 1, 1869. The statue of Maj. Gen. John F.

Reynolds, "one of the finest portrait statues ever created to honor the

heroes of the Civil War," was done by John Q. A. Ward and

unveiled on August 31, 1872. Caspar Buberl did much of the artwork on

the New York State Monument, located near the plot of New York's dead

and unveiled on July 2, 1893. The Gettysburg Address Memorial, which

stands near the west gate of the cemetery, includes a bust of Lincoln

sculpted by Henry K. Bush-Brown and was dedicated on January 24,

1912.

|

CSA DEAD GATHERED FOR BURIAL (GNMP)

|

Immediately after the battle, as Wills worked to establish the

Soldiers' National Cemetery, another Gettysburg attorney,

David McConaughy, purchased tracts of

land on East Cemetery Hill, Culp's Hill, and Little Round Top. He did

this to ensure their preservation and in doing so launched one of

America's pioneer efforts in historic preservation. In September 1863

McConaughy and other Gettysburg citizens formed the Gettysburg

Battlefield Memorial Association, and in April 1864 the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania incorporated the association to "hold and preserve" the

battlefield and, with memorials, commemorate the deeds of "their brave

defenders." The association added to the holdings acquired by

McConaughy, and in 1880 a Union veterans' organization, the Grand Army

of the Republic, took control of the association. In 1878 the Strong

Vincent G.A.R. Post of Erie, Pennsylvania, erected a memorial on Little

Round Top to mark the place where Col. Strong Vincent was killed.

The Vincent memorial was the first erected outside of the national

cemetery, but many followed as northern states erected memorials to their units

that had fought in the great battle. In the meantime Gettysburg became a

popular site for veterans' reunions and a mecca for tourists.

|

PHOTOGRAPH OF VETERANS OF 23RD PENNSYLVANIA AT MONUMENT DEDICATION

(GNMP)

|

The Memorial Association had performed a great service in initiating

the preservation of the field as a great memorial, and in 1894 its

holdings included over 600 acres dotted with over 300 monuments and

seventeen miles of roads. In 1895 these holdings were turned over to the

War Department as the nucleus of Gettysburg National Military Park. The

park, which became a part of the National Park System in 1933, now

preserves much of the battlefield and honors the men of both armies

that fought at Gettysburg.

|

THE DEDICATION OF THE NATIONAL CEMETERY NOVEMBER 19, 1863

(From Indianapolis Daily Journal of 2l November 1863)

Cemetery Hill occupies the bend of the hook. On its crest is the very

handsome little cemetery belonging to the town, which lies a half mile

or so to the north, and formed part of the battle ground. Just below

this cemetery, on the slope facing the broad valley, lies the National

Cemetery. It looks out upon the blue mountains into which they

retreated.

I do not know the exact size of it, but should suppose there were

some fifteen or twenty acres in it. The graves are arranged in a

semi-circle, the convex side toward the valley, of probably six or eight

hundred feet diameter. They are completed, so far as to show the general

plan, but not so far as to show the arrangement of the various States

upon it fully.

The dead of Indiana are not yet all reburied. There are thirty-one

now here. They lie in two lines, filling the extent of our section, with

a third still incomplete. The exterior of the three has every grave

marked, with the head boards made, as I judge from the worn and defaced

appearance, when the bodies were first buried, under some tree, or some

hillside, by their companions.

I was more interested in the grounds, and the brave dead resting in

them, than the ceremony, inspiring as it was, as full of great names

come to honor great deeds. I could not see very much of it. Few did, I

fancy, though full 20,000 came for nothing else. The procession and the

ceremonies were appropriate and admirable.

The platform for the President, Cabinet, Foreign Ministers,

Governors, and other magnates, was erected nearly on the line of the

diameter across the semi circle of the Cemetery, and the crowd filled

the interior.

In the procession to the Cemetery were long glittering lines of

troops headed by Generals with dashing staffs and interspersed with

scarlet-colored and plumed bands and grouops of civilians, regiments of

Odd Fellows and Masons with their gay trappings, all moving to the sound

of cannon from that knob of Cemetery Hill, where our guns played so

frightfully in earnest on the 3d of July. James Blake of our city was

one of the two Chief Marshals, and never looked so well before as at the

head of that really grand procession.

Mr. Lincoln rode on horseback—nobody used cartridges—and

his deeply cut features looked hard and worn. Mr. Seward and Mr. Usher

rode on each side of him with a long string of attendents behind. Gov.

Morton at the head of some Indiana delegation, rode on horseback.

The procession was a long time getting itself placed around the

stand. As soon as it could be silenced out a few hundred feet into the

throng, leaving the outside still rushing and rustling and grumbling

because everybody else wouldn't be still, the band played a solemn,

grand air, and Rev. Thomas Stockton prayed I couldn't hear one word.

Nor did one-tenth of the crowd. But it is no matter, it will be

published. The President's speech I couldn't hear either and it closed

the ceremony.

Berry Sulgrove, Editor

Indianapolis JOURNAL

|

PRESIDENT LINCOLN AS HE APPEARED ON NOVEMBER 8, 1863,

ELEVEN DAYS BEFORE THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS. (USAHMI)

|

|

<

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

Gettysburg

|

|

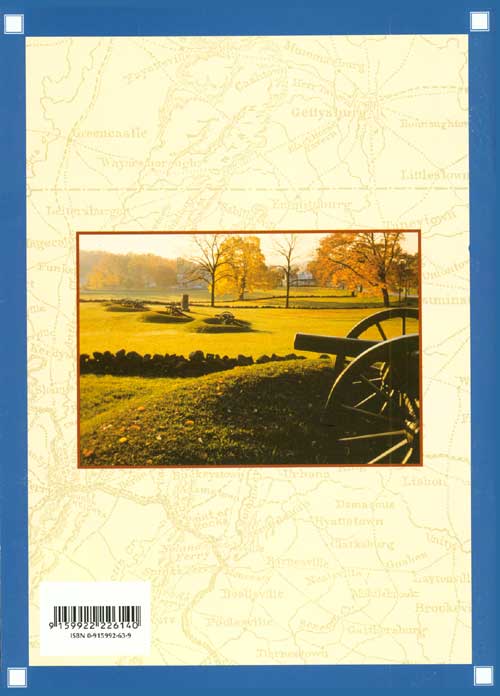

Back cover: Photograph of Cemetery Hill by Russ Finley.

|

|

|