|

THE PRISON CAMP AT ANDERSONVILLE

Included in this book are short histories of the other Civil War

prison camps and entries from the diaries of some of the

prisoners.

|

In the very beginning of the Civil War, prisoners of war were

exchanged right on the battlefield, a private for a private, a sergeant

for a sergeant and a captain for a captain. In 1862 this system broke

down and caused the creation of large holding pens for prisoners in both

the North and South. On July 18, 1862, Major General John A. Dix of the

Union Army met with the Confederate representative, Major General Daniel

H. Hill, and a cartel was drafted providing for the parole and exchange

of prisoners. This draft was submitted to and approved by their

superiors. Four days later, the cartel was formally signed and ratified,

and became known as the Dix-Hill Cartel.

The Dix-Hill Cartel failed by mid-year, for reasons including the

refusal of the Confederate Government to exchange or parole black

prisoners. They threatened to treat black prisoners as slaves and to

execute their white officers. There was also the problem of prisoners

returning too soon to the battlefield. When Vicksburg surrendered on

July 4, most of those Confederate prisoners who were paroled were back

in the trenches within weeks.

|

EXCHANGE FOR THE CAPTURED WAS AN UNCEREMONIOUS EVENT. HERE SEVERAL

HUNDRED CONFEDERATE PRISONERS AWAIT THEIR EXCHANGE AT COX'S LANDING.

(USAMHI)

|

The discussions on exchange lasted until October 23, 1862, when

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton directed that all commanders of places

of confinement be notified that there would be no more exchanges. This

decision would greatly affect the large numbers of prisoners in northern

and southern prison camps. The so-called "holding pens" now became

permanent prisons. Among the prisoner-of-war camps in the North were

Camp Douglas in Chicago and Johnson's Island and Camp Chase in Ohio. In

the South were Libby Prison and Belle Isle in Richmond and Camp Florence

in South Carolina.

Through the latter part of 1863, the two prisons in Richmond became

overcrowded. This condition plus severe food shortages made Confederate

officials look for a more suitable location to build a prison. Their

search took them south, far from the fighting around Richmond.

Captain W. Sidney Winder was selected to find a suitable location in

Southwest Georgia. When Winder reached Milledgeville, the Georgia

capital, Governor Joseph E. Brown introduced him to members of the

legislature from the southwest counties of Georgia. Winder proceeded to

Albany, but property owners discouraged him. He then traveled to

Americus, where Uriah Harrold, a purchasing agent for the Commissary

Department, informed him of Andersonville on the Southwestern Railroad.

According to Winder the location had a "large supply of beautiful clear

water."

In evaluating the area, Winder settled on the site in the third week

of December 1863. The property was in Sumter County (now part of Macon

County), five miles west of the Flint River and 1,600 feet east of the

Andersonville Depot. There were approximately twenty people living in

the town of Andersonville so opposition to the prison was nil. The

property owner, Benjamin B. Dykes, received $50.00 per year for the use

of the land. The site was selected and named Camp Sumter for the county

it was located in. Soon the prison was simply known as

Andersonville.

With the site selected, the next step was to begin construction. The

responsibility belonged to the Quartermaster Department. Selected for

the job was Richard B. Winder of Maryland, a cousin of Captain W. Sidney

Winder and a nephew of Brigadier General John H. Winder, who was

provost marshal general of the Richmond area and would later oversee all

prison camps in the Confederacy east of the Mississippi.

|

AFTER THE CARTEL OF EXCHANGE HAD BEEN AGREED UPON, AIKEN'S LANDING ON

THE JAMES RIVER IN VIRGINIA WAS MADE A POINT FOR EXCHANGE IN THE EAST.

COMMISSIONERS MET WITH PRISONERS BROUGHT FROM EITHER RICHMOND OR FT.

MONROE, EXCHANGED ROLLS, AND WORKED THEIR EXCHANGES. THEY HAD A TABLE OF

EQUIVALENTS IN WHICH THE PRIVATE WAS THE BASIC UNIT OF EXCHANGE.

(USAMHI)

|

In January 1864 the work began, with slaves digging the ditch and

felling the trees for a prison that would house 10,000 prisoners. The

pine trees were cut to twenty-two feet in length with five feet set in

the ground and seventeen feet standing above the ground. The slaves used

broad axes to make all sides flat so that the prisoners could not see

the outside of the prison. The stockade was built with two gates, the

South Gate and the North Gate. By the time the stockade was completed in

the third week of March, there were eighty sentry boxes at forty yard

intervals. The prison interior also had a deadline which was about

nineteen feet from the stockade wall. The guards had orders to shoot any

prisoners who walked across the deadline.

|

A PERIOD MAP OF THE ANDERSONVILLE REGION. (LC)

|

|

LIBBY PRISON

Libby Prison was located in Richmond, Virginia, in a building which

was incorrectly called a tobacco warehouse. It was originally the

establishment of William Libby & Son, Ship Chandlers, 20th &

Cary Streets. It was a four-story building containing eight rooms. The

men slept on the floor. There was a water closet on each floor that

became a privy which rendered foul air and polluted the entire building.

The prison was opened in April 1861 and was closed in April 1865. The

total number of prisoners held during its existence was approximately

25,000. This was primarily an officers' prison.

The prisoners cooked their own rations with inadequate fuel, the

rations furnished were inadequate, and there was a shortage of clothing

and blankets. Rations consisted of beef, bacon, flour, beans, rice and

vinegar. Of those who died at Libby, 6,276 are buried in a cemetery in

Henrico County southeast of Richmond, two miles from the city and one

and a half miles from the James River. There are 817 known graves and

5,459 unknown. Some of the bodies came from Belle Isle, Hollywood,

Oakwood and the poorhouse cemeteries in Richmond.

|

(CHICAGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|

|

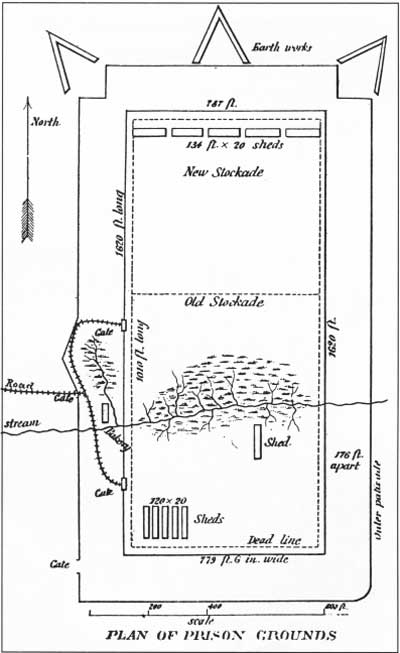

PLAN OF THE STOCKADE AND SURROUNDINGS AT ANDERSONVILLE FROM CENTURY

MAGAZINE.

|

Initially, the guards were members of the 55th Georgia, commanded by

Lt. Colonel Alexander W. Persons, and the 26th Alabama. Their stay at

Camp Sumter was temporary. Brigadier General Howell Cobb was ordered to

command the newly authorized Reserve Corps of Georgia. He established

his headquarters at Macon and proceeded to enlist guards for

Andersonville. In the beginning of May the first two regiments of

Georgia Reserves arrived at the post, and the two veteran regiments were

relieved to take part in the spring offensive of General Joseph E.

Johnston's Army of Tennessee. The third regiment of Georgia Reserves

reached Andersonville on May 11. Most of the new guards were old men or

young boys with a smattering of veterans who had been wounded in

battle.

|

LOUISIANA ZOUAVE PRISONERS IN THE GUARD-HOUSE AT FORTRESS MONROE.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

|

PLAN OF PRISON GROUNDS, ANDERSONVILLE, THE STOCKADE. MEASURED BY DR.

HAMLIN IN THE SUMMER OF 1865.

|

The first batch of prisoners, 500 strong, arrived on February 25

(some accounts say prisoners arrived the 24th), and were turned into the

stockade even though it stood unfinished and food and equipment were in

short supply. Before authorities could get the situation in hand and get

the prison into proper order, they were swamped by an unceasing influx

of prisoners, some 400 arriving every day.

Food and containers to hold rations were in short supply. Prisoner

Charles C. Fosdick, Co. K, 5th Iowa Infantry stated, "We were put to our

wit's end to know how to receive our rations. We had no vessels except

our little coffee cans, and many did not have even these. Some would

draw in their hats, mixing meal, peas and beef all together; others

would tear out a shirt sleeve, tie a string around one end, and draw in

it, and others would draw theirs in a corner of their blouse." During

the month of March the rations consisted of cornmeal, beans and an

occasional ration of meat. As the prisoners kept pouring into the

stockade this ration gradually diminished.

The prisoners were divided into detachments of 270 men. They were

again subdivided into three companies of ninety men each with a sergeant

in charge. They received their rations through their sergeant who

divided them as equally as he could. By the end of March, there was

"nothing but corn meal and a little salt."

|

IN 1994 TO COMMEMORATE THE 130TH ANNIVERSARY OF ANDERSONVILLE PRISON,

THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE PRESENTED A LIVING HISTORY PROGRAM TO RECREATE

LIFE AT THE PRISON. (NPS)

|

|

A SKETCH OF PRISONERS RECEIVING RATIONS. FROM LIFE AND DEATH IN REBEL

PRISONS, BY ROBERT H. KELLOGG, 1866.

|

March 27, 1864

Sometimes we have visitors of citizens and women who come to look

at us. There is sympathy in some of their faces and in some a lack of

it.

John L. Ransom

Sergeant, Co. A.

9th Michigan Calvary

|

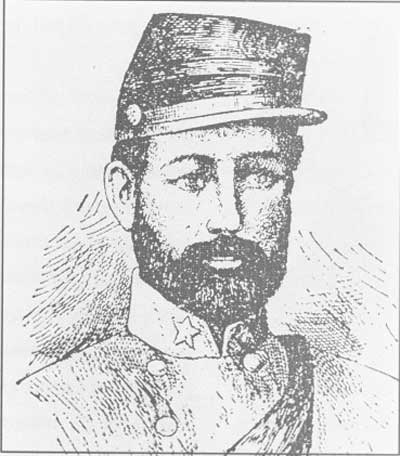

It was on March 27 that Captain Henry Wirz was ordered to

Andersonville to take charge of the inside of the prison and all of the

prisoners. Heinrich Hartmann Wirz was born November 25, 1823, in Zurich,

Switzerland. His interests lay in the medical field, and he did have

some medical training, but his father objected and insisted that he

enter the mercantile field. He sailed to America in 1849. When the Civil

War began he joined the 4th Louisiana Infantry and was wounded during

the battle of Seven Pines. The wound was incurable and would be an

object of pain for the rest of his life.

By April 1, the stockade designed for 10,000 men held 7,160

prisoners. Between that date and the 8th of May, 5,787 men arrived from

various places; 728 died, 13 escaped and 7 were recaptured, making a

total of 12,213 inmates. As Richard Winder was to admit later, he had

made a grievous error in placing the bakery and cookhouse upstream from

the prison. They polluted the stream that the prisoners used for

drinking and bathing.

Death came from the introduction of contagious diseases into the

camp, pollution of the prisoners' drinking water within the stockade,

inadequate hospital accommodations, the lack of prisoner quarters,

exposure to the elements, bad sanitary practices, short and defective

rations and overcrowding. Upon their arrival the first prisoners saw

that there was no shelter from the elements, so they constructed what

they called "shebangs." The prisoners constructed huts and lean-tos from

logs, limbs, shrubs and brush left within the prison.

|

CAPTAIN HENRY WIRZ

Henry Wirz was born on November 25, 1823 in Zurich, Switzerland and

was educated in Italy and Zurich. He emigrated to the United States in

1849 and in 1854 was married in Kentucky to a widow with two children.

They had one child from their union. The family moved to Louisiana, and

when the Civil War broke out he joined Company A, 4th Battalion,

Louisiana Volunteers. He was given a battlefield commission in the

battle of Seven Pines where his right arm was shattered and was not to

completely heal for the rest of his life. After his exploits at Seven

Pines he was made a captain and was assigned to work for General Winder,

superintendent of military prisons. He first worked at Libby Prison in

Richmond and then, in July 1862, he was sent to command the Confederate

Prison at Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Because of Wirz' nationality and

education, President Davis made him a special minister and sent him to

Europe to carry secret dispatches to the Confederate Commissioners. He

returned from Europe in January of 1864 and on April 12, 1864, he

arrived at Andersonville, Georgia, to command the military prison

there.

|

|

They also used blankets, tent flies, overcoats and clothing from the

dead. Some prisoners used the prison yard to make bricks which when

placed one upon the other became their shebangs. There was no effort in

the beginning by the Confederate administration or the prisoners

themselves to properly design or lay out streets, so the shebangs went

in all directions. This disorganization and lack of proper camp

administration probably led to a higher mortality rate.

|

AN ILLUSTRATION OF CITIZENS VIEWING THE CAMP. (NPS)

|

Many of the letters, manuscripts and diaries written during and after

this prison experience spoke of the same things: the loneliness,

dejection and the complete gloom of despairing individuals. G.E.

Reynolds, Co. F, 86th Ohio Infantry, recalled his arrival at

Andersonville by writing, "As the heavy wooden door closed behind us my

heart sank within me, and hope which till that time had buoyed me up,

fled. And such a sense of utter and hopeless desolation crept over me as

I hope never to feel again." Asa Isham, Co. F, Michigan Cavalry, wrote,

"Until now, we have not believed that the government we had voluntarily

joined in protecting could abandon us, after faithful service, to the

tender mercies of our enraged and barbarous enemies."

|

SERGEANT JOHN L. RANSOM WAS ONE OF MANY PRISONERS WHO KEPT DIARIES.

|

|

A PHOTO OF THE "PRISONERS" FROM THE NPS LIVING HISTORY PROGRAM. (NPS)

|

April 8, 1864

We sometimes draw cow peas for rations, and being a printer by trade,

I spread the cow peas out on a blanket and quickly pick them up one at

a time, after the manner of picking up type. One drawback is the

practice of unconsciously putting the beans into my mouth. In this way I

often eat up the whole printing office.

John L. Ransom

|

The officials at the prison had a great need for lumber and tools so

that they could erect some type of barracks and other facilities for the

prisoners. But most of the lumber that arrived was used for building

outside of the prison.

The following letter was written by R.B. Winder, captain and

assistant quartermaster at Andersonville, to Major J.G. Michaeloffsky,

quartermaster at Macon, Georgia on April 11, 1864:

SIR: Captain Armstrong brings me the information that a train load

of lumber has been waiting transportation at Gordon for the last twelve

days. The great want and emergency for this lumber at this post requires

it of me to ask you to exercise your official authority in placing it

here at the earliest possible moment. The instructions forwarded to post

quartermasters in relation to Government transportation fully warrant

your taking the most decided and prompt action in this case. The very

great emergency, as far as the need of it here requires, safely excuses

me in requiring you to act in this matter. I am burying the dead without

coffins. I shall rely entirely upon you. If it is not here in a

reasonable period I shall he compelled to report the matter to the

authorities at Richmond.

|

|