|

September 1, 1864

From the fourth of July until the first day of September, every day

in those two months, I killed three hundred lice and nits. When I got up

to this number I would stop killing until the next day.

Edmund J. Gibson

Pvt., Co. K,

25th Maryland Inf.

|

It was the beginning of winter and the guards relaxed much of their

sternness and rigor. The prisoners entered into conversation with them,

and trading became more prevalent. The prisoners made toothpicks out of

bones from the meat they were fed. They made pipes out of green wood

that they picked up while outside the stockade. Prices for the items

depended on the amount of time a prisoner put into his pipe or

toothpick. Another business opportunity was called "raising" in which

the amount of a Confederate note was increased. The script was poorly

made, both in design and execution. The prisoners always tried to get

change in "ones" or "twos." The $1 bill would be converted into a $10

bill and the $2 bill would be made into a $20 bill. The counterfeiter

guaranteed his work and style of art to his customers.

|

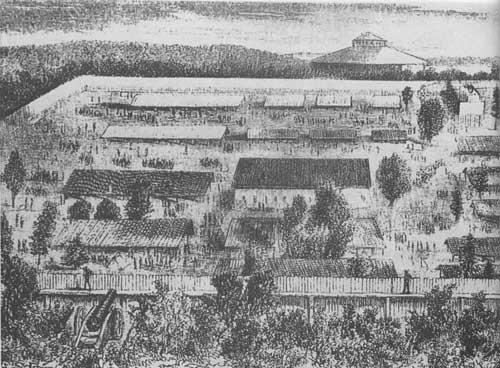

CAMP OGLETHORPE

Camp Oglethorpe Prison was located near Macon, Georgia. It was used

to confine Union military officers during the last full year of the

Civil War, 1864. The officers survived well. No ill-treatment was noted

by the over 1,600 officers confined at Macon. Only one officer was shot

and killed by a Confederate sentinel for crossing the dead line. The

camp was located south of Macon on a sandy incline formerly used as the

county fair grounds. Shelter was provided for the Union prisoners as

well as water and wood for heating. The old Floral Hall, a one-story

frame building located in the center of the fair ground, was used to

house 200 men. A stockade 16 feet high and similar in construction to

the Andersonville stockade, surrounded the enclosure.

A raid on Macon in late July by General George Stoneman's cavalry

persuaded Confederate authorities to remove prisoners from Macon to

Charleston and Savannah. By the end of September 1864 the prison

virtually ceased operation.

|

(NPS)

|

|

|

PRISONERS ENTERING ANDERSONVILLE PRISON ILLUSTRATION FROM BATTLEFIELD

AND PRISON PEN.

|

|

ELMIRA PRISON

Elmira, New York, is situated five miles from the Pennsylvania line.

In the beginning the camp was used for new recruits, but by May 15,

1864, some of the barracks were set aside for prisoners-of-war. A

twelve foot-high fence was constructed, framed on the outside with a

sentry's walk four feet below the top and built at a safe distance from

the barracks. Housing consisted of thirty-five two-story barracks each

measuring 100 by 20 feet. Two rows of bunks were along the walls and as

the prison became crowded some prisoners lived in "A" tents.

The first group of prisoners, shipped from Point Lookout, Maryland,

arrived at Elmira on July 6 and numbered 399 men. By the end of July,

4,424 prisoners were packed in the compound with another 3,000 en route.

By mid-August the number leaped to 9,600. The inmates of Elmira

weathered hunger, illness and melancholia but, even worse, exposure to

the elements. Late in the winter of 1864-65 some stoves were distributed

to the prisoners but not enough for everyone. The southerners were

exposed to temperatures of ten to fifteen degrees below zero and many

succumbed to freezing.

Of the total of 12,123 soldiers imprisoned at Elmira, 2,963 died of

sickness, exposure and associated causes. The camp was officially

closed on July 5, 1865. All that remains today of Elmira Prison is a

well-kept cemetery along the banks of the Chemung River.

|

(LC)

|

|

September 13, 1864

On the 13th of September the only remaining one of my company died,

leaving me alone as far as my company was concerned. This event made me

very sad. I, the youngest boy in the regiment, and sick besides, I

nerved up for the worst and resolved to stand the thing through, that I

might tell the poor boys' friends where they died.

Charles Fosdick

|

On November 8 the prisoners held an election for President. Four

thousand six hundred votes were cast, Lincoln secured a 734 majority.

The prisoners hoped he would be as successful at home.

Although the hot summer and over-crowding were over, the lice,

graybacks as they were called, kept up their steady work. As one diarist

wrote, "I tried to bear it but matters grew worse, till I hobbled out to

a guard's fire nearby and begged a firebrand. Taking the blazing pitch

pine brand and going back into the tent, I took off my clothes and

killed over 400 graybacks by actual count. They were as large as a very

large kernel of wheat, and the scars where they bit me I shall carry to

the grave.

|

ANDERSONVILLE PRISONERS WHO HAD WASTED AWAY TO LIVING SKELETONS WERE

PHOTOGRAPHED AFTER BEING EXCHANGED. THESE PHOTOS WERE LATER PUBLISHED IN

NORTHERN NEWSPAPERS AND USED AS PROPAGANDA AGAINST THE SOUTH AND USED AS

EVIDENCE TO HELP CONVICT CAPTAIN WIRZ. (LC)

|

|

1867 PHOTO SHOWS THE COVERED WAY, WITH THE MIDDLE STOCKADE ON THE RIGHT

AND THE THIRD STOCKADE WALL ON THE LEFT. (NA)

|

|

FORT DELAWARE

Fort Delaware prison was located on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware

River. Approximately 33,565 Confederate prisoners passed through during

its existence. The prison was constructed as a fort to protect northern

cities. A 12-foot-deep, 30-foot moat surrounded the prison. The granite

walls were seven to thirty feet thick. The prison was plagued with the

usual diseases and malnutrition of all prisons north and south during

the Civil War.

At this prison 2,436 Confederate prisoners died. Their bodies were

transported by boat to the New Jersey side of the Delaware River and

buried in trenches at a place called Inns Point. A towering granite

obelisk marks the spot and at its base are plaques with the names of the

soldiers in the common grave.

|

(USAMHI)

|

|

September 19, 1864

A priest belonging to the Catholic church was almost daily among

us, and worked faithfully among the sick and dying members of his own

church. He had also always a kind word for all of us.

John W. Urban

|

In the latter part of November, four or five wagon loads of

vegetables were brought in by the citizens of nearby Americus. The

vegetables were never distributed to the prisoners and were consumed by

the authorities of the prison. In December the toll continued with 165

deaths. The grounds of the stockade looked like a battlefield with

abandoned shebangs and items such as cups, canteens and worn-out

clothing strewn throughout the grounds. It had been a battlefield in

some sense. Many, many deaths occurred here as the nearby cemetery could

testify. These men had not been torn apart by bullets but by loneliness,

disease, malnutrition, filth and vermin. They didn't die fast but

slowly, perhaps remembering their wives, children, mothers and

fathers.

At the beginning of December 2,000 prisoners arrived from Salisbury,

North Carolina. On December 22 in a letter to General Cooper, inspector

general of the Confederacy, General Winder wrote, "Savannah evacuated.

Had not the prisoners from Columbia, Salisbury and Florence better be

removed immediately to Andersonville. Only one road now open by way of

Branchville to Augusta. I think there is not a moment to be lost. Please

answer at once." General Winder would die of an apparent heart attack

while on an inspection trip to Salisbury Prison on February 6, 1865.

|

CAMP FLORENCE

Camp Florence was located in Florence County, South Carolina and was

one of the largest Southern Civil War prisons. The prison was 23 acres

in size and was enclosed by a wall of logs 12 feet high. An embankment

outside the wall stood three feet below the top of the wall and served

as a walkway for the guards. No tents or shelters were furnished to the

prisoners. Wood was left inside the stockade and the first arrivals used

the wood for huts and cooking. Lack of adequate food, pure water,

sanitation facilities and shelter was responsible for 20 deaths per

day.

The prison was open for five months from September 1864 to February

1865. Between 15,000 and 18,000 Federal prisoners passed through the

gates, and 2,802 died within the compound. Florence National Cemetery,

in Florence, South Carolina, consists of 5-3/4 acres. Because the

listing of the deaths was lost, there are 2,1167 unknowns.

|

October 23, 1864

As for myself, I never felt so utterly depressed, cursed, and

God-for-saken in all my life before. All my former experiences in

battles, on marches, and at my capture were not a drop in the bucket as

compared with this.

Walter E. Smith

Pvt., Co. K

14th Illinois Infantry

|

As December 25 approached, Michael Daghtery, 13th Pennsylvania

Cavalry, surely spoke for many of the prisoners when he wrote, "On

Christmas Day thinking of our friends at home enjoying themselves, and

how we are situated here no rations of any kind. Little of our friends

at home think we are in this situation. God grant them health to enjoy

many more. This is my sincere wish to my poor mother and sister. I hope

I will see them soon."

Prisoners were again arriving daily. It was cold and wet, a typical

Georgia December. To beat the cold some would band into groups and lay

next to each other all night and most of the day to stay warm. They

would only leave this huddled mass to answer roll call and receive their

rations. Graybacks could also interrupt their attempt at warmth. Private

Lassel Long, 13th Indiana Infantry, related that, "As soon as we would

begin to get a little warm they would commence their daily and nightly

drill. They would have division, brigade, regiment, and company drills,

ending up with a general review. When those large fellows began to

prance around in front of the lines it would make some one halloo out,

'I must turn over, I can't stand this any longer.' So we would all turn

to the right or left as the case might be. This would stop the chaps for

a short time."

|

THE BODIES WERE LAID TO REST SIDE BY SIDE IN SIX-FOOT WIDE BY THREE-FOOT

DEEP TRENCHES. THIS PHOTO AT THE CEMETERY WAS TAKEN IN THE SUMMER OF

1864. (NA)

|

|

ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY OF RELEASED PRISONERS

EXCHANGING THEIR RAGS FOR NEW CLOTHING.

|

The new year claimed 197 deaths its first month. Four thousand to

five thousand arrived from other prison camps during January with most

of them occupying the south end of the prison. At the end of January,

Captain Wirz complained about the prisoners stealing hospital property

and selling it to the guards. There were also frequent escapes from the

hospital. Wirz mentioned in a letter dated January 21 that a covered way

and a third stockade wall had been started but asked whether this new

stockade should be finished or the six-foot-high fence around the

hospital be torn down and a real stockade built around the hospital to

stop the stealing, trading and escapes. The covered way was never

completed and a stockade around the hospital was never started.

December 29, 1864

We sit around our scanty fires shivering and hungry thinking of what

good times we might enjoy were we permitted to be at home. We endeavor

to keep a stiff upper lip.

George M. Shearer

Private, Co. E,

17th Iowa Infantry

|

According to historical documents the winter of 1864-1865 was the

coldest winter in twenty five years in southwest Georgia. One night the

temperature was eighteen degrees above zero. The prisoners were poorly

clad and the wood they attempted to burn for warmth was too wet to do

much good. Toward the end of January more new prisoners were brought in.

As Charles Fosdick wrote, "We old dried skeletons gathered around them

in such great numbers that it is a wonder they did not get frightened to

death at our ghostly appearance.

February began more pleasantly than the long cold month of January.

The captives knew that if Sherman had been defeated there would have

been a larger influx of prisoners. The only ones coming in were

prisoners from other locations in the South. The weather broke with

pheasant and warmer days. The prisoners took more exercise, and they

even began to sing patriotic songs. For the first time in twelve months

the boys were optimistic. The rumors were good rumors: exchange, the end

of the war, going home. Private Lassel Long wrote that a newly arrived

prisoner made a speech to many of the prisoners saying, "I tell you this

blasted rebellion cannot succeed. It was born in sin and cradled in

iniquity, and it is going to pieces like a ship driven upon a rock. Bill

Sherman is at this time cutting a swath through South Carolina forty

miles wide." At this point the prisoners began cheering, and after they

had cheered until they were hoarse, someone started up, "Rally around

the flag, boys," then it was taken up all over the camp.

|

AN 1867 PHOTOGRAPH OF THE CEMETERY. (NPS)

|

|

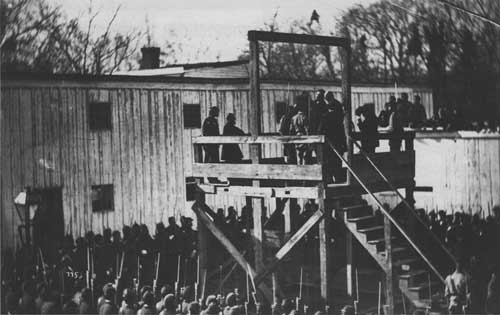

THE EXECUTION OF HENRY WIRZ

Historians who have studied the tragic episode of Andersonville agree

that even in the grip of understandable hysteria after President Abraham

Lincoln's assassination, an indefensible travesty of justice was

committed against Captain Henry Wirz. Worn and haggard, he was still at

his post when Union Captain Henry E. Noyes arrived at Andersonville in

early May with orders for his arrest. Noyes took Wirz to Washington

where a military commission tried, convicted, and sentenced him to hang

for: (1) conspiring with Jefferson Davis, Howell Cobb, John H., Richard

B., and W.S. Winder, Isaiah H. White, R. Randolph Stevenson, and others

to "Impair and injure the health and to destroy the lives.., of large

numbers of federal prisoners.., at Andersonville" and (2) "murder, in

violation of the laws and customs of war." Wirz was tried under these

charges, convicted and sentenced to death. The sentence was carried out

on November 10, 1865, on the courtyard of old Capitol Prison.

|

(LC)

|

|

February 24, 1865

Our clothes were nearly worn out, and we had to go around and seek

out the dead and rob them of the clothes they had in order to keep from

freezing to death ourselves.

Bjorn Aslaksan

|

In March death still visited Andersonville Prison. One hundred and

eight died, mostly prisoners in the hospital. Through the guards,

prisoners learned that the Yankees had captured Selma, Alabama, and

would soon be coming. New prisoners, and there were very few, brought

only good news. Still, at Andersonville rations were just enough to keep

the prisoners alive. On March 25, 800 prisoners left and there was talk

that a train would leave every day full of prisoners. On March 28 new

prisoners brought word that General Wilson's Cavalry was on the way.

In April the end of the war was in sight. Twenty-eight died during

this last full month of Andersonville's existence. Most of the prisoners

were sent to Vicksburg for exchange. Slowly but surely the prisoners

left Andersonville. When Union forces finally arrived at Andersonville

in May, about three weeks after the war had ended, only a small number

of prisoners remained. Arrangements were made to transport these sick

and frail soldiers home. While the prisoners waited, Andersonville

claimed its last victim.

March 7, 1865

In March, 1865, we began to hear rumors of the advance of our

forces from the guards, and to look forward with hope to the time when

we should once more be free.

Thadeus L. Waters

Private, Co. G,

2nd Michigan Cav.

|

It was over. The ground now was bare of the living. Where only a

short time before had been masses of living and dying there was now an

assortment of discarded blankets, handmade cooking utensils and worn-out

clothing. In only fourteen months, 12,914 had died on this ground. Their

sacrifice will always be remembered, their experience never

forgotten.

What became of the prisoners who left Andersonville? Hundreds

perished on their way home when the steamboat they were on, the

Sultana, exploded and sank near Memphis, Tennessee. Countless

others died in northern hospitals, or in their hometowns of the diseases

incurred during their captivity at Andersonville.

|

ON JULY 25, 1865 CLARA BARTON ARRIVED IN ANDERSONVILLE WITH AN

EXPEDITION OF 37 MEN. WITH THE HELP OF DORENCE ATWATER'S DEATH LIST, SHE

MARKED THE GRAVES OF THE PRISONERS WHO HAD DIED WITH PAINTED BOARDS. SHE

HELPED TO DEDICATE THE CEMETERY ON AUGUST 17, 1865. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

|

MEMORIAL DAY AT ANDERSONVILLE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE. (NPS)

|

Over the years, the finger of blame has pointed in many directions,

but the facts show that events of the time made this national tragedy

happen. As the war dragged on and the exchange system collapsed,

thousands of prisoners-of-war, Union and Confederate alike, found

themselves in hastily constructed and poorly supplied prison camps. Many

never returned to their homes, families or friends. At Andersonville

human misery reached its zenith. The tombstones in Andersonville

National Cemetery and the written words of the prisoners tell a tragic

story.

|

Andersonville National Historic Site

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

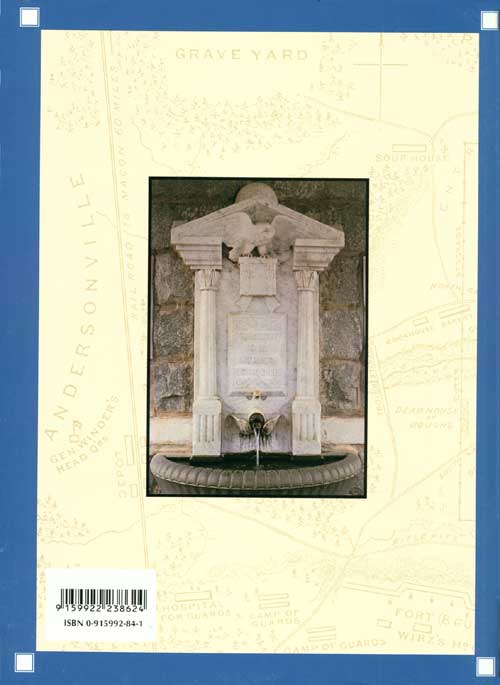

Back cover: Photograph of the Providence Spring Memorial at

Andersonville National Historic Site. (NPS)

|

|

|