|

|

ROCK ISLAND PRISON

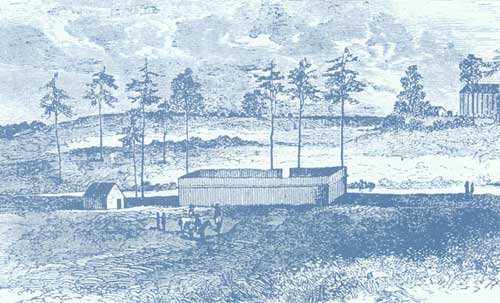

Rock Island Prison was located on a government owned island between

Davenport, Iowa, and Moline, Illinois. For the past century it was known

as Rock Island Arsenal. The prison camp was constructed in mid-1863 and

received its first prisoners that December. The prison camp was

comprised of 84 prisoner barracks, each being 100 feet long, 22 feet

wide and 12 feet high. A kitchen was built into each barracks. They had

60 double bunks, and each building could house 120 prisoners. Also, over

a period of time other buildings were erected: a laundry, guardhouse,

dead house and dispensary.

The barracks were enclosed by a stockade fence 1,300 feet long, 900

feet wide, and 12 feet high. A boardwalk was constructed on the outside

of the fence, and sentry boxes were placed every 100 feet.

During the 20 months the prison was open, 1,960 prisoners died and

171 Union guards died. The Confederate cemetery was located 1,000 yards

southeast of the prison stockade. Prison guards were buried on a site

about 100 yards northwest of the Confederate cemetery.

|

August 12, 1864

We had a chance to look around and see what the storm had done for

us. The entire prison, including the swamp, was swept in such a manner

as to be quite clean compared to its former condition. Almost all the

filth and vermon on the ground was swept away. It was soon discovered

that a strong, pure spring of water had burst out. The water was cool

and pure in great contrast to the filthy stuff we had been using.

John W. Urban

|

The framework of the barracks was completed in September. There were

four barracks that housed 270 prisoners each. When the men started

moving in, two more barracks were nearing completion. They were near the

north end in the new section of the prison. During September 2,677

prisoners died. Between the end of February, when the prison was

established, and September 21, a total of 9,479 prisoners had died, or

23.3 percent of those who had been confined at Andersonville. The death

register listed the greatest killer as diarrhea (3,530 deaths) and

dysentery (999 deaths). The two together accounted for 58.7 percent of

the deaths during the first six months.

Starting in September, some of the healthier prisoners were moved in

detachments from Andersonville to Camp Lawton at Millen, Georgia, and to

Florence, South Carolina. The prisoners were moved not only because of

overcrowded conditions but also due to the movement of Sherman's army

near Atlanta. Some men believed they were part of a general exchange of

prisoners. S.M. Dufur, Co. B, 1st Vermont Cavalry wrote, "We said it can

not be any worse if we are even going to another prison, it will be

change." By September 8, five thousand or more had left. With the exodus

of so many prisoners the sick and dying became more obvious to the

bystander.

|

WHEN A.J. RIDDLE TOOK THIS PHOTOGRAPH ON AUGUST 17, 1864, THERE WERE

ALMOST 33,000 PRISONERS CONFINED WITHIN ANDERSONVILLE'S 26-1/2 ACRES.

(LC)

|

|

FATHER WHELAN

Father Peter Whelan was born in 1802 in County Wexford, Ireland and

migrated to America while still a young man. He became a priest in the

Catholic Church and spent 19 years at a church in Locust Grove, Georgia.

Early in the Civil War his ministry took him to Fort Pulaski to minister

to the Confederate troops. He was taken prisoner when Fort Pulaski fell

but after a short time was paroled. Father Whelan heard of Andersonville

and the privation that existed there. With the sanction of the church he

made the trip to Andersonville and arrived on June 16, 1864. He stayed

until October, ministering to the prisoners at the risk of his own

health. He borrowed $16,000 in Confederate money and in January 1865

went to Americus and bought ten thousand pounds of wheat flour. Baked

into bread and distributed at the prison hospital, it lasted several

months. This became known as "Whelan's Bread." One prisoner said

afterward, "Without doubt he was the means of saving hundreds of lives."

|

Sick prisoners who could not get into the hospital were moved into

the new barracks, which were only slightly more comfortable than a

hovel in the ground. Henry Milton Roach, Co. G, 78 Ohio Infantry, wrote,

"One of the most pitiful scenes that came before any observation was

that of a man of middle age, who through patriotism, had sacrificed the

dearest ties to man, that of leaving wife and children, all that his

country and flag might live. This man became insane and believed he was

at home with his family, describing all of the circumstances of his home

life. This poor victim whom I have described was finally released by

death, but the last lingering word from his lips was "Mary."

|

THE OFFICERS' STOCKADE AT ANDERSONVILLE WITH THE HOSPITAL AND GUARDS'

BARRACKS IN THE DISTANCE. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

August 13, 1864

Occupying a wall-tent near our dispensary was a lady with a young

child. I at first supposed that she was the wife of one of the officers

in charge, but soon learned that she was a prisoner, having been

captured in company with her husband, who was steamboat captain and a

civilian.

Solon Hyde

Private,

17th Ohio Infantry

|

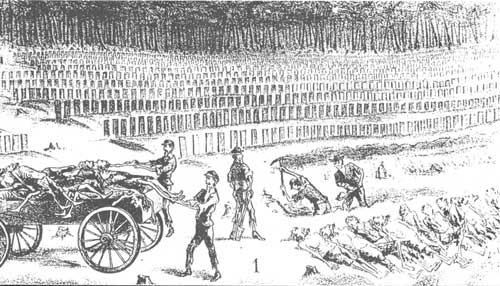

Some of the parolees' duty outside the prison was to bury the dead.

They dug trenches about one hundred and sixty feet long and three feet

deep with a one foot deep vault at the bottom. They split slabs of wood

and placed them over each of the dead. James R. Compton, Co. F, 4th Iowa

Infantry, wrote, "It is no small task to bury one hundred and twenty men

each day. So badly would they decompose during the interval between

death and burial that often we found, when we attempted to lift them,

that the skin slipped from the flesh, and often the flesh cleared from

the bone. Here comes a government wagon piled full of our brave boys;

thrown into the wagon like a lot of dead swine, to be rudely thrown out

again on their arrival at the burial ground."

It was the end of September and the stockade that had held over

30,000 a few weeks earlier was nearly empty. Only those who could not

walk remained, besides the prisoners who had to work on the outside of

the prison to keep it operating.

Those who did remain continued to find ways to occupy their time. As

William B. Clifton, Co. K, 37th Indiana Cavalry, wrote, "Well, we had to

have some kind of amusement and so they had lice races. They could get a

tin plate and make a small ring in the center of the plate, heat it in

the sun, drop two lice on the center of the plate, and bet on the one

getting out of the ring first. One person would say, 'drop' and the lice

were dropped on the plate and the lice would start to run to get off of

the hot plate. I seen poor fellows crawl up to look at the lice race

that would be dead in thirty minutes."

August 19, 1864

Each morning, at 9 o'clock, a lone drummer appeared at the south gate

and beat "sick call", when the worst cases of sick would be carried up

and examined by two attending physicians, a few of which would be

admitted to the hospital and the rest returned to their respective

divisions. The same drummer thumped away each morning to summon the camp

to deliver up its dead.

Charles Fosdick

Private, Co. K,

5th Iowa Infantry

|

In a letter dated September 29, 1864, Major General H.W. Hallux,

chief of staff of the Union Armies, wrote J.G. Foster, who was in charge

of exchange of prisoners at Hilton Head, South Carolina. In the letter

Hallux stated, "Hereafter no exchange of prisoners shall be entertained

except on the field when captured. Every attempt at special or general

exchange has been met by the enemy with bad faith. It is understood that

arrangements may be made later toward exchange of sick and disabled men

on each side."

By the first of October, Andersonville ceased to be a receiving depot

for prisoners. Only those who could not travel were left. It became a

prison hospital. But with such a high proportion of the prisoners left

being sick the mortality rate rose dramatically. Besides the 8,218

prisoners present on October 1, another 444 were added during the month.

Of those 8,662 men, 3,913 received treatment in the hospital and of

these 1,560 died. Twenty eight escaped and 2,811 were transferred to

other prisons.

|

INTERRING THE DEAD, AS ILLUSTRATED

BY THOMAS O'DEA, 1885. (NPS)

|

|

POINT LOOKOUT PRISON

Point Lookout Prison was located at the extreme tip of St. Mary's

County, Maryland, at the confluence of the Chesapeake Bay and the

Potomac River. The size of the camp was 1,000 feet square, about 23

acres, surrounded by a board fence 12 feet high with a platform on the

outside for the guards. The prisoners were housed in tents. The tents

were arranged on nine streets or divisions running east and west. The

prison was opened July 1863 and closed June 1865. Twenty thousand, one

hundred and ten prisoners went through the facility during its

existence, and 3,389, or 17%, died. The deaths came from bad management,

lack of adequate supplies such as clothing, blankets, wood and food,

failure to establish sanitary conditions, and brutality and senseless

killing by the guards.

|

|

NPS VOLUNTEERS PORTRAYING CAMP LIVING CONDITIONS. (NPS)

|

It was reported by the surgeon in charge, R.R. Stevenson, that with

the overcrowding of the prison now over, the incidence of mortality at

the post was decreasing and that a careful analysis of the soil and

water proved that Andersonville was one of the healthiest places in the

Confederacy. He also reported that they were building sheds and other

suitable hospital buildings and in the course of one month ample

accommodations would be made for 2,000 patients at Andersonville. He

called attention to the importance of preventing the crowding of

prisoners at any other post.

The prisoners now had a roll call every morning and were formed into

detachments of 500 each. There were approximately 2,500 healthy men and

1,280 sick. The rations now included bread baked in cakes or loaves

about two feet square and four inches thick. The prisoners received soup

in boots, bootleg buckets, and drawer and pantaloons legs secured at the

bottom. Although the food had improved somewhat and the crowding was

over, the death rate was still high.

|

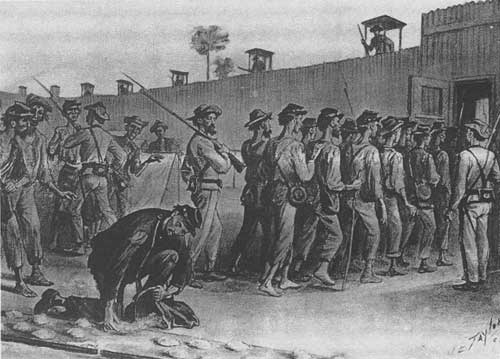

LEAVING ANDERSONVILLE, ANDERSONVILLE MILITARY PRISON SERIES BY

J.E. TAYLOR, 1898. (LC)

|

In November 499 died. There were 1,359 prisoners on hand. Captain

Wirz complained about prisoners escaping every night because he did not

have enough guards.

|

PRISON GUARDS AT ANDERSONVILLE

During most of the prison's existence the Georgia Reserve comprised

the guard. Most of them were young boys or old men. During the 14 months

of the prison's existence, over 200 of them died. Most of these (117)

were buried nearby. When the cemetery wall was erected in 1878, the

guard cemetery was left outside the wall. The United Daughters of the

Confederacy, which had been saving money for a monument, used the funds

to have the bodies disinterred and moved to Oak Grove Cemetery in

Americus.

|

According to the Sanitary Commission in the North, from July to

November 1864 they sent to Andersonville 5,000 sheets, 7,000 pairs of

drawers, 4,000 handkerchiefs, 600 overcoats, blankets, shoes canned

milk, coffee, farina, cornstarch and tobacco in corresponding

quantities. This could not overcome the effects of over-crowding, the

stinking swamp nor the lack of shelter and medicine.

|

|