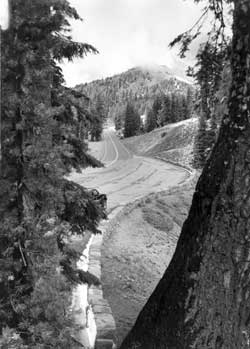

Crater Lake from a parking

area on the north side of the rim above Steel Bay.

|

|

Design and Construction of Circuit Roads

Only one road ran through Crater Lake

National Park when Congress established it on May 22, 1902. The Fort

Klamath — Jacksonville wagon road served as an approach route for

visitors to the lake, though they still needed to follow a trail marked

by blazes for the final 2.5 miles to the rim. A better road on the

other side of the Cascade Divide (one going through Munson Valley)

reached the site later called Rim Village in 1905, but those desiring to

do a circuit around Crater Lake were faced with a cross-country pack

trip lasting several days.

The first clamor for a circuit road came from

park founder William G. Steel, but only after he started a concession

company to provide visitor services at Crater Lake in 1907. Steel told

one newspaper that the road's construction was imminent that September,

an announcement that largely stemmed from his optimism about public and

private investment at Crater Lake, as fueled by visits from Secretary of

the Interior James R. Garfield and railroad magnate Edward H. Harriman,

president of the Southern Pacific. Garfield left office after the

presidential election of 1908, while Harriman died soon thereafter, but

Steel continued his pursuit of funding for roads both to and within the

park through the Oregon congressional delegation. His first taste of

success in this regard came in June 1910, when Congress appropriated

$10,000 for the Army Corps of Engineers to make a survey and provide

estimates for future road construction at Crater Lake.

A party of twenty-six men began work to

prepare plans, specifications, and estimates for a park road system in

August. The engineer in charge came to Crater Lake having studied a

topographic map and quickly becoming convinced that a "main highway" or

"boulevard" following the rim was feasible, with roads and trails to

points of interest radiating from it. As the center of circulation,

such a road followed long established precedents, given how circuits for

riding and walking had served as the standard way of viewing European

parks since the eighteenth century. Prominent landscape designers in

the United States during the middle part of the nineteenth century like

Andrew Jackson Downing embraced this convention as the desire for public

and private parks spread across the Atlantic. It was Downing who

provided a hierarchy of service, approach, and circuit roads in his

work, and this heavily influenced the design of circulation systems in

American national parks. The concept of a circuit road could also be

applied at various scales, particularly where this device presented

visitors with appealing views and distant prospects. For these reasons

surveyors considered a road encircling the lake to be of "first

importance," in that it should follow the "ridges and high points along

the crater rim on account of the view." Approach roads to Crater Lake,

by contrast, were to possess little in the way of scenic

features.

Building the first Rim

Road

Estimates for construction of a complete road

system in Crater Lake National Park also reflected the emphasis on a

circuit of the rim. Roughly two-thirds of the $627,000 needed to

complete the grading for this system in 1911 would go to building the

"main highway," one that the Army Corps of Engineers wanted to locate as

"near to the edge of the crater as can be done at as many points as

possible." They figured an average cost of building each mile of road

to be $13,000, with the construction estimates based on a roadway 16'

wide shoulder to shoulder and an eventual surfaced width of 12'. This

figure did not include paving at another $5,000 per mile, nor the need

to build a guard wall as a safety barrier. The engineer in charge of the

survey, however, believed that the latter could be hand laid with "dry

rubble" without increasing the total estimated cost.

Road building started during the summer of

1913, with work supervised by the Army Corps of Engineers continuing

over the next six years. Construction proceeded from the park's east

entrance to Lost Creek, where the Rim Road was to commence. Crews hired

on a day labor basis, rather than on contract, started a circuit from

there. One group went north toward Kerr Notch and then to the top of

Anderson Point in 1913, while another crew worked from a permanent camp

established in Munson Valley to reach the rim and continue west.

Assistant Engineer George E. Goodwin had immediate charge of the

project, which in 1913 also involved a number of refinements to road

location indicated by the survey done three years earlier.

Taken from the West Rim

Drive with Watchman in the distance.

|

Much of the construction was accomplished

through either hand labor or equipment like horse-drawn road plows and

graders. Progress in clearing and rough grading could be slowed,

however, by the considerable amount of needed excavation by hand with

picks and shovels in some places. The likelihood of continuing

appropriations from Congress allowed for multi-year commitment by the

Army Corps of Engineers at Crater Lake, so Goodwin reported on

experiments with various kinds of road surfacing in 1913. This step

would follow the grading phase, of course, but the engineers needed to

find which type of surfacing could best withstand the climatic

conditions and anticipated traffic. They compared various treatments on

short sections of road in Munson Valley and found that a combination of

an oil bound macadam and bituminous paving held the most promise.

Despite having a small rock crushing plant and

a wood fueled steam roller available during the surfacing experiments,

lack of funds for surfacing prevented the engineers from completing

anything more than a rough graded road around the rim over the next five

seasons. Crews completed grading and installation of cross drainage

(wood planks in a few places at first, but corrugated metal culverts

later predominated) of two segments on the Rim Road in 1914. One

connected Lost Creek with the permanent camp in Munson Valley and

covered 10 miles, while the other went from Kerr Notch to the summit of

Cloudcap, a distance of 4 miles. Having 250 men and fifty teams (many

with drag scrapers) during August made a huge difference over 1913,

especially since three steam shovels handled most of the excavation.

Appropriations for the work dropped in 1915,

so the grading on Rim Road was limited to a section of 3.5 miles between

Rim Village and the foot of Watchman. An average force of fifty-five

men, six teams, and one steam shovel worked from July to October, with

much of the work heavy excavation. The steam shovel handled much of the

rockwork, often after drilling and blasting, with finish grading done by

hand and teams. Despite the relatively slow progress with grading and

installing cross drainage, the engineers reported having settled on a

final location for the remaining road construction between the Watchman

and Cloudcap.

The heavy winter followed by a cold spring and

a labor shortage limited the 1916 season to just 3 miles between

Watchman and the Devil's Backbone, on the highest portion of the western

rim. At that point about two-thirds of a projected 35.6 miles of Rim

Road had been rough graded, with the engineers commenting that the

newest section "provides many advantageous viewpoints of the lake and

many beautiful outlooks on the surrounding country." Grades varied

between 2 and 10 percent on the already built road sections, with no

curve being less than 50' in radius and very few being less than 100'.

Without surfacing material, however, the Rim Road was bound to become so

badly rutted and dusty that automobile travel on it was described as

"slow, disagreeable, and in some places dangerous."

Closing the loop around the rim took two more

seasons. Work continued from both ends in 1917, when 100 men and

fifteen teams cleared, graded, and installed cross drainage from the

Devil's Backbone and then around Llao Rock to a point above Steel Bay on

the northwest side of the lake. A separate contingent of sixty men and

ten teams completed a switchback descent from the top of Cloudcap to the

Wineglass, where a temporary shelter cabin was built. Day labor thus

completed the grading of 6 miles despite a continuing labor shortage

that put park road projects in competition with haying and harvesting

operations in the nearby Klamath Basin.

Virtually all of the $50,000 appropriation for

building roads at Crater Lake in 1918 went to the Rim Road, with most of

that amount going toward rough grading of the last 6 miles from Steel

Bay to Wineglass. Enough work had been completed by the end of September

to allow the first vehicles to complete the entire Rim Road circuit.

American involvement in World War I made the labor shortage more acute

and snow conditions dictated a late start, but double shifts that often

had the two steam shovels working sixteen hours a day allowed the

engineers to close the construction camps in early October.

The engineers came back to Crater Lake in

1919, using the unexpended balance from allotments made the previous

season to do a small amount of grading and repair on the Rim Road before

transferring all property, materials, and supplies to the National Park

Service in July. Work had progressed to the point where NPS director

Stephen Mather thought it economical for his bureau to assume the

responsibility for park roads, even though the engineers saw their

project as only 50 percent complete. They pointed to the need for

surfacing and paving in every annual report to the Secretary of War

since 1913, but no funds for these phases of road construction had been

forthcoming, even after a grand total of approximately $417,000 had been

expended for equipment, supplies, and labor as of 1919 for grading a

system of roads and trails in the park. Well over half that amount was

spent on the Rim Road, a project that remained unfinished throughout the

following decade.

The Need for Reconstruction

The National Park Service assumed control of

the roads in Crater Lake National Park once the engineers departed, but

available funding allowed crews to open the circuit each summer by hand

shoveling, followed several weeks later by horse drawn equipment that

removed rocks from the roadway. By 1923 Park Superintendent C.G.

Thomson lamented to NPS director Stephen T. Mather that a rising number

of vehicles made maintenance difficult in the absence of surfacing

material, since the annual re-grading each fall could not adequately

alleviate the problems associated with a rough dirt road. Publicly,

however, Thomson extolled the numerous wonders seen from the Rim Road in

promoting the park to visitors. According to him, the circuit should be

seen as "not a joy ride, but a pilgrimage for the devotees of Nature."

It was where "a hundred views of the magic blue lake and its huge

shattered frame" highlighted the "thirty four miles of amazing beauty,

three hours of vivid and changeful panorama." He knew what 200 cars per

day over the course of nine weeks each summer could do to such an earth

graded road, but Thomson counseled prospective visitors to "approach the

experience [of driving around the rim] in a leisurely and appreciative

mood, and great will be your reward."

No matter how reverent the motorist, few

considered the Rim Road to be adequately constructed as passenger cars

became heavier and faster during the 1920s. Within a decade of the

circuit's "completion" by steam shovel and horse-drawn grading

equipment, the narrow roadway made passage of vehicles headed in

opposite directions difficult. Even though the average radius of curves

"greatly exceeded" 100', with none being less than 50', they seemed

tight by the highway standards of 1926. Curves needed to be lengthened

so drivers could better sustain the posted speed throughout their

journey around the rim. Grades varied from 2 to 8 percent (with some

stretches of road at 10 percent for short distances), representing

another design problem at a time when engineers agreed that a 5 percent

grade should be the maximum allowed.

Metamorphosis of the Rim Road into a new

circuit of Crater Lake took place as the state highway system and forest

roads around the park experienced both steady and dramatic changes

spurred by an infusion of federal highway funds expended through the

Bureau of Public Roads (BPR). The road system in Oregon grew with the

help of funds authorized by the congressional acts of 1916 and 1925 that

were aimed at providing the states with aid in building highways. The

BPR subsequently supervised contracts to upgrade approach roads to the

park, such as the Crater Lake Highway (numbered as 62 after 1926), which

had been part of the state system beginning in 1917. It also took the

lead in the improvement of the federal system of roads, such as U.S. 97

(also known as The Dalles — California Highway) that served as the

main north-south corridor through central Oregon, one that ran just east

of the park.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, several roads

built in the national forests near Crater Lake became part of the state

highway system, including one connecting Union Creek with the south

shore of Diamond Lake, and then over to U.S. 97. The most profound

effect on the park visitation from building new roads, however, came in

1940. Realignment of U.S. 97 away from Sun Mountain and Fort Klamath

dramatically reduced visitor traffic through the east entrance, but

opening the Willamette Highway (numbered 58) from the north allowed park

visitors to save about two hours over what had been the quickest route

from Eugene. Previous work to provide a passable road through the park

(much of it involved upgrading the Diamond Lake Auto Trail into the

North Entrance Road) to a new "north entrance," in concert with the

effort to connect Diamond Lake with U.S. 97 played an important part in

the park's visitation reaching the unprecedented figure of 252,000 that

year. At that point the western portion of the Rim Drive began to serve

as both through route and a portion of the circuit road around Crater

Lake.

Designing a new "Rim

Drive"

On the most basic, functional level, there

are several main reasons as to why the NPS and BPR undertook

reconstruction of the Rim Road. The reasons addressed ameliorating a

narrow, rough, dusty road with sharp curves and steep grades.

Significant increases in visitation during the 1920s brought more

traffic to the park, though at least one observer noticed that the

existing road was so difficult to traverse that only a small proportion

of motorists attempted to go around the lake.

View to the north of Wizard

Island Overlook, with clouds obscuring the top of

Watchman.

|

The NPS wanted the new Rim Drive to be a more

pleasant visitor experience, but wanted to avoid creating a

super-highway on which motorists "would speed around the lake and pass

by scenes of beauty in their rush to make the lake circuit." BPR

engineers thereby aimed for a constant average design speed of 35 miles

per hour that would avoid gear-shifting on ascent or braking on descent.

Instead of the switchbacks and short radial curves evident in places

along the old road, designers preferred curvilinear alignment that

allowed vehicles to maintain the design speed despite curves and changes

in grade. These alignments allowed for constantly changing views by

making use of continuous (also called reversing) curves instead of long

straight sections (tangents), and eliminated the need for cuts and fills

that would be both unsightly and expensive.

Engineers who located the first Rim Road

attempted to provide viewpoints of the lake in as many places as

possible. The location diminished the interest inherent in being routed

away from the lake in some sections, as well as the excitement

experienced by visitors in reaching certain viewpoints by trail. The

road also created some scarring evident from a few places on the rim

since the Army Corps of Engineers had virtually no funding to address

landscape concerns, even if such expertise had been available.

Designers of Rim Drive aimed for visual unity in reconstructing the

road, which included removing it from what visitors saw from the main

focal points, or vistas. Unity encompassed the consolidation of park

facilities and integrating trail location and design with that of the

road.

Another rationale behind reconstructing the

Rim Road lay in providing an intended, rather than incidental, link

between a road circuit presenting central features and its

interpretation to visitors. John C. Merriam, who probably served as the

leading figure in creating a formalized interpretive program at Crater

Lake, remained adamant that the road primarily serve the purpose of

"showing the great features" of the lake and its caldera. He thus

decried any attempt to make it a link in a larger through route

connecting various points and thought it best to avoid allowing any part

of the Rim Road to become a segment of the park's approach roads. The

circuit was instead be part of a plan aimed at presenting features of

the region "determined by experts to be of outstanding importance."

Merriam thought that Crater Lake offered "one of the greatest

opportunities for teaching fundamental understanding of

Nature."

With Crater Lake showing "the most extreme

elements of beauty and power in contrast," the plan included the

development of "stations" where certain views helped visitors appreciate

"elements derived from the geological story of Crater Lake and those

arising from elements of pictorial beauty." Merriam cautioned, however,

that the "hand of the schoolmaster" not be overly evident at these

particular places. The most overt attempt to educate visitors would

instead be made at the Sinnott Memorial in Rim Village, a place Merriam

referred to as "Observation Station No. 1." He saw it as the "main

project," though "minor projects" of building the road, some trails, as

well as additional observation stations had to be closely coordinated

with developing the Sinnott Memorial for visitor orientation.

Where interpretation had formerly been

incidental to the experience of traveling Rim Road during the 1920s, the

slow metamorphosis of reconstruction was intended to bring this function

to visitors in a more concrete way. Each of the seven observation

stations built as part of Rim Drive were intended to serve as stops on

the naturalist-led caravan that traversed the road in a clockwise

fashion, from Rim Village to Sun Notch. All were chosen for their part

in displaying a different aspect of the lake's beauty. Spaced

proportionately around the lake, designers intended to each have

hard-surfaced parking for a minimum of fifty cars.

Plans for each observation station were to

match the "unique beauty of the lake itself," since Merriam thought the

lake represented "a supreme opportunity to teach the significance of

beauty through offering to the visitors the experience of beauty." The

points chosen by Merriam and his associates on the western side of the

rim were accessible by trail so that the road would not come near enough

to the station to create "a disturbing element to one who wishes to

observe the lake in quiet." This was something of a contrast with the

four stations located on the northern or eastern side of the lake, which

became part of the planning and design of the road. NPS landscape

architect Francis G. Lange designated three of the four stations (Skell

Head, Cloud Cap, and Kerr Notch) as "parking overlooks."

Merriam wanted a leaflet describing the

stations of Rim Drive to be available at the Sinnott Memorial, in

conjunction with adequate signs at each station. These stops might also

include an inconspicuous holder for literature describing the station

for those who did not visit Rim Village first. As a designer, Lange

supplied a more detailed vision for the stations adjoining the road.

They should contain, in his words,

"a small promontory circulation point with

the necessary stone guard rail (log, if found more suitable) and an

interestingly treated sign distinguishing the point in question, as well

as denoting any other unusual features. It is also suggested that a

suitable mounted binocular glass be set up at each point where found

desirable, being mounted on an appropriate stone base."

For those stations accessible by trail, Lange

recommended stone steps if necessary, then a small promontory

platform, some treatment of guard rail, possibly a sign and then a

binocular mounted on a stone base."

Beneath the observation stations in a

hierarchy of developed viewpoints along Rim Drive lay the substations,

numbering thirteen in 1934, but increased (at least in plans) to

seventeen a year later. Substations shared many similarities with the

observation stations in that they were chosen for aesthetic or

educational reasons, but differed in that they did not function as stops

on the caravan trip, nor were all of them formally developed with paved

parking areas, signs, or masonry guard rail. Unlike the stations, they

sometimes highlighted features situated away from Crater Lake and often

focused on specific geological features.

Developed pull outs or "parking areas" served

as the next level below the substations in the hierarchy. Although not

chosen at random, these stopping points lacked the aesthetic values

attributed to the observation stations and substations. Lange commented

in 1938 about an effort to restrict the number of such points. Where

"an interesting view of the Lake can be obtained," he wrote, an effort

"has been made to provide accommodations." He also noted in the same

report that where "excellent" views of the hinterland existed, several

small parking areas were provided.

Preserving the primitive "picture" of Crater

Lake received greater emphasis from the engineers and landscape

architects as they planned the reconstruction of Rim Road than the

interpretation of beauty and geological features. Merriam stressed

Crater Lake and its rim was one of the three most beautiful places in

the world and that every effort should be made to keep the road from

imposing on views of Crater Lake or the surrounding region. Landscape

architect Merel Sager described how the greatest damage to park

landscapes came from the construction of roads and urged that an

"intelligent and comprehensive program of roadside development" could

better fit these roads into their surroundings. This meant attention

had to be paid to the road as seen in the landscape and the landscape as

seen from the road.

Rim Drive followed the old Rim Road wherever

possible to minimize impact. Landscape architects and the foremen under

contract also paid special attention to planting the noticeable cuts in

new sections and trying to disguise (or "obliterate") abandoned

stretches of old road when funding allowed. Contract provisions called

for protecting all trees not within the clearing limits (or "right of

way"), placing dark soil and trees on conspicuous cuts and covering

fills to diminish the ragged appearance of large rocks. Another

dimension to the work involved "bank sloping," where flattening and

rounding was aimed at stabilizing cut and fill slopes to permit

establishment of vegetation, while warping aided the transition between

the bank and roadway. All of these measures reflected the standard

practice of using landscape treatments to contribute to the utility,

simplicity, economy, and safety of scenic highways built primarily for

the enjoyment of motorists. The national parks received special

attention in this regard, partly because the NPS pioneered many of the

standardized landscape treatments in road design.

NPS Collaboration with BPR

The NPS gained a measure of control over its

need to continually upgrade park roads in the face of increased vehicle

speeds and a massive increase in automobile ownership with passage of

legislation in 1924 authorizing annual appropriations specifically for

this purpose. After working to solidify a working relationship with BPR

over the next year or so, NPS director Stephen T. Mather signed an

inter-bureau agreement on January 18, 1926. Under its terms, the NPS

and BPR were to use "every effort to harmonize the standards of

construction" they employed with those of the Federal Aid Highway system

located outside the parks, while at the same time securing the "best

modern practice" in locating, designing, constructing, and improving

park roads. The inter-bureau agreement stipulated that the NPS

reimburse BPR for overhead expenses from the annual appropriations for

park roads. This included various levels of investigation and survey,

the preparation of bid documents (derived from the plans,

specifications, and estimates, known as PS&E), as well as salaries

for engineers to supervise and inspect contracted work.

Once initiated, projects followed a familiar

sequence that began with road location. After reconnaissance, engineers

did a preliminary survey (or P-line) of the road location to obtain

topography for representative cross sections. The P-line allowed for

curvature and connecting tangents to be placed by "projection" back in

the office, a step resulting in the semi-final location (or L-line).

Staking in the field, or final location, necessitated the establishment

of benchmarks on the ground, as well as any adjustments to grade or

positioning of cross-drainage. All stages of road location were subject

to NPS approval, with most of the changes provided by landscape

architects.

The process of road design along Rim Drive was

shared between the BPR and NPS. At a landscape scale, BPR designed

three basic elements of the road: horizontal alignment, vertical

alignment, and cross-section. The design of curves and tangents in a

planar relationship is horizontal alignment, with preference given to

use of spiral transition curves instead of tangents throughout most of

the circuit. These made for a sympathetic alignment in relation to the

park landscape, but also brought average speed and design speed closer

together for the purposes of safety. Vertical alignment or "profile" is

how the located line in plan view fits the topography in three

dimensions, especially in reference to grade, sight distance, and cross

drainage. The banking or "superelevation" of curves represented one

particularly significant part of vertical alignment, since adequate

sight distance in relation to the design speed needed to be maintained,

particularly where a combination of curvature and grade occurred. The

third element, cross-section, is a framework in which to place

individual features and their relationship to each other. Features such

as road width, crown, surface treatment, and slope were usually depicted

through drawings of typical sections.

At the scale of individual features, the NPS

worked to provide the BPR with standard guidance for the design of road

margins (shoulder, ditch, bank sloping), drainage structures (culvert

headwalls and masonry "spillways"), and safety barriers (masonry and log

guardrails) along Rim Drive. As the lead NPS landscape architect for

much of the project, Francis Lange produced planting plans in

conjunction with a number of site plans for areas along the road

corridor that needed individualized treatment beyond the standard

measures described in the contract specifications.

Scott Bluffs parking area

with Mount Scott in the distance.

|

Road construction consisted of three types of

contracts beginning with the grading phase. There were numerous items

on which contractors bid on the basis of unit prices for each. BPR

engineers, in consultation with NPS engineers and landscape architects,

provided estimates for the items, starting with clearing vegetation from

the roadbed. Removing stumps and other obstacles to rough grading

through blasting or burning constituted a separate item called grubbing.

The subsequent rough grading with heavy machinery began with

excavation, usually divided into separate bid items called

"unclassified" and "Class B," with the latter often specified by the NPS

to avoid damage to natural features. Rough grading also included items

such as moving excavated material based on estimated volumes needed for

cuts and fills, placement of concrete or metal culverts as

cross-drainage, as well as the flattening of slopes at prescribed ratios

to control erosion. Completing the earth-graded road involved several

items under the heading of "finish grading." This step included fine

grading of the sub-base and shoulders, as well as bank sloping.

Depending on how much funding was available, subcontractors handled the

stone masonry for culvert headwalls, guardrails, and retaining walls at

this stage. Other subcontracted items under the heading of finish

grading included old road obliteration and special planting once bank

sloping had been accomplished.

With the grading phase completed, a separate

contract for preliminary surfacing could be let. This next phase of

road construction involved laying a base course of crushed rock on the

roadway, followed by a top course of finer material to provide a

definite thickness and protection for the earthen road underneath. This

type of contract might include items, usually subcontracted, such as

building masonry structures like guardrails (often on fills created

during rough grading that had to settle over the winter) or special

landscaping provisions to be completed as part of executing site plans

or working drawings provided by the NPS.

Bituminous surfacing, or paving with asphalt,

was done through another contract. This phase of road construction

involved laying aggregate (crushed stone and sand) along a specified

width of roadway as a base, followed by placing a bituminous "mat" as

binder. The thin surfacing of bitumens known as a "seal coat" served as

the final step. Completion of the paving contract generally signified

the end of BPR involvement with construction. Road maintenance and post

construction items thus became NPS responsibility.

Reconstructing 3 miles of approach road

between Park Headquarters and Rim Village set the NPS/BPR collaboration

in motion at Crater Lake. With the location survey completed several

months prior to formal approval of the inter-bureau agreement, the

grading contract commenced during the summer of 1926. The project

reduced the maximum grade (from 10.9 percent to 6.5 percent) of this

approach and produced a new roadway 20' in width. As a precursor to

reconstructing the Rim Road, this realignment became known for how

visitors obtained their first view of Crater Lake as a spectacular and

sudden scenic encounter. Landscape architects with the NPS chose the

point of "emergence," one allowing visitors to enter a new "plaza"

developed on the western edge of Rim Village or begin a circuit around

the lake.

The initial step in planning for

reconstruction of the Rim Road took place once the inter-bureau

agreement had been signed. The BPR reconnaissance survey of the park's

road system in 1926 furnished a starting point and allowed

Superintendent C.G. Thomson to reference estimated construction costs in

a report on his priorities for road and trail projects over the next

five years. NPS officials in Washington requested the report in

connection with allocating the congressional appropriation for park

roads and trails, a separate process from the site development plans of

the period that were aimed at facilities for areas like Rim

Village.

Rudimentary lists of projects with estimated

costs evolved over the next five years into a bound set of drawings by

landscape architects showing the proposed site development in the

context of projected park-wide circulation. Formal adoption of these

"master plans" by the NPS came as appropriations for park development

steadily increased, but these documents remained apart from planning for

the location and design of roads. BPR accomplished these tasks through

its usual process prior to letting contracts for road construction,

subject to NPS approval. Master plans contained some information about

Rim Drive and other road projects, but only as context for what the NPS

landscape architects hoped to accomplish in a "minor developed area"

such as the Diamond Lake (North) Junction or at the "parking overlooks"

like Kerr Notch, Skell Head, or Cloud Cap.

Road Location

The idea of better positioning the park for

through travel in reference to the location of U.S. 97 drove

Superintendent Thomson's priorities in his report about possible road

and trail projects in 1926. A rerouted East Entrance Road received top

choice for the time being, but Thomson wanted the west Rim Road improved

"as soon as appropriations would permit" in order to better "take care

of travel from Crater Lake to Diamond Lake." He reasoned that this

section received more use than any other on the Rim Road, thereby

meriting consideration when more money became available, especially

since a new location near the Watchman might help get the entire circuit

open earlier in the season. Given the park's short season, Thomson

emphasized the importance of the Rim Road to the visitor experience by

describing the circuit as "easily one third of the value of our Park and

until it is fully open, thousands of people are denied" what he called

"their greatest reaction."

The BPR reconnaissance survey not only

allowed Thomson to reference the construction estimates in his

priorities, but also allowed him to comment on proposed road locations.

It designated the Rim Road as Route 7 in the park and divided the

circuit into five segments, labeling them as A, B, C, D, and E. Thomson

took an immediate dislike to what BPR proposed as 7-E, a road segment 4

miles long and running from Sun Notch to Crater Lake Lodge by way of

Garfield Peak. In addition to being very expensive, the proposed road

location necessitated two tunnels and a "gash across the face" of

Garfield Peak, which, as Thomson stated, was "altogether too beautiful

to be subjected to the unconscious vandalism of ambitious

engineers."

Oddly enough, given his comment on the

location of 7-E, Thomson endorsed what BPR proposed for segment 7-D. He

envisioned that "all travel will enter the pinnacles (East) entrance"

and then proceed to the rim to enjoy what Thomson thought to be the

preeminent view of Crater Lake at Kerr Notch. In spite of the cut

required across the face of Dutton Cliff on two sides, he enthused about

how vehicles might travel "practically on contours" to Sun Notch.

Visitors could thus enjoy a panorama of the Klamath Basin and the

"tumbled" Cascade Range.

In urging that segment 7-A be given first

priority for fiscal year 1929, Thomson stated that the stretch of road

between Rim Village and the Diamond Lake (North) Junction constituted

"practically a main stem for us." It not only carried traffic to and

from Diamond Lake, but also was the most traveled section used by

visitors who did not go all the way around the rim. He believed

construction of this 6.7 mile segment might take only one season, to be

followed by the other segments over the next four years. In response,

BPR conducted a preliminary location survey as another step toward

construction during the summer of 1928. Beginning from Park Headquarters

in Munson Valley, they went over Thomson's preferred line for 7-E to Sun

Notch in July and then pushed toward Kerr Notch on the reconnaissance

line for 7-D. The location crew left Crater Lake at the end of

September, having run a P-line for those two segments as well as the one

connecting Rim Village with the Diamond Lake Junction. They did so

abruptly, after receiving word from Albright that there would be no

funding for road construction at the park in 1929.

The delay may have been fortuitous since

Thomson transferred to Yosemite National Park in early 1929 and the new

superintendent, E.C. Solinsky, wanted additional study of the P-line and

segment 7-A in particular. One of his reasons pertained to a plan for

building a new administration building at Rim Village. Solinsky

believed that such a structure obviated the need for a ranger station

there, so the latter could be located at the Diamond Lake Junction.

Since he intended it to serve as an entrance (checking) station,

Solinsky recommended postponing the building programmed for 1929 until

the location of the junction could be finalized.

Another reason for further study pertained to

Merriam's desire for designing roads and trails "with special reference"

to presenting park features and those in the surrounding region "which

have been determined by experts to be of outstanding importance." The

Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial supplied a grant for a study of the

educational possibilities of the parks in 1928, one administered by a

committee headed by Merriam. Most of the field visits associated with

the study took place over the next summer, followed by recommendations

to congressmen well positioned in the appropriations process. At Crater

Lake the study effort translated into money for building the Sinnott

Memorial with a special $10,000 appropriation as well as funds to hire a

permanent park naturalist and an expanded summer staff of

naturalists.

Merriam visited the park in August 1929 and

paid special attention to the location of Rim Drive. He then wrote to

Albright about the need for someone who understood the park's geological

features to assist with locating segment 7-A. The recommendation

brought about an on-site inspection of the P-line in October 1929,

beginning at Rim Village and going clockwise on the old road to Kerr

Notch. Arthur L. Day, volcanologist at the Carnegie Institution of

Washington and head of its Geophysical Laboratory, served as Merriam's

representative. Joining him at the meeting were the district and

resident BPR engineers (J.A. Elliott and John R. Sargent, respectively),

as well as NPS chief engineer Frank Kittredge, chief NPS landscape

architect Thomas Vint, and Solinsky.

The group recommended keeping the road as

close to the rim as possible over the first mile from Rim Village, but

with additional easy curvature to the first volcanic dike visible at the

Discovery Point Overlook. They suggested elimination of a tight radial

turn at the foot of the Watchman, and then chose a line that kept the

road away from views of Crater Lake until the Watchman Overlook.

Kittredge noted how BPR appeared to have "solved" the snow problem

around the Watchman, presumably by running a lower line than the one

adopted by the old Rim Road.

BPR opted for a low line around Llao Rock,

though the group favored a spectacular "ledge route" involving sidehill

excavation and a series of "window tunnels" on the lake side to obtain

better views and reduce 2 miles of travel in reaching Steel Bay.

Everyone came to agreement over leaving the Rock of Ages (Mazama Rock)

undisturbed. All of the group members wanted the road to reach the top

of Cloudcap, but no one thought of marring the fringe of whitebark pine

overlooking the lake. This portion of the circuit required further

study, the group advised, especially if it stayed close to the rim. The

group endorsed the surveyed line between Cloudcap and Kerr Notch, with

the stipulation that visitors should be able to reach the viewpoint for

Cottage Rocks (Pumice Castle), as well as the Sentinel Point and Kerr

Notch localities.

Although the group did not review the P-line

between Kerr Notch and Sun Notch, Kittredge characterized it as

requiring heavy blasting to make a roadway across sheer cliffs. He saw

no way around blasting, but thought damage could be limited if care was

used in preventing material from "flowing" down slopes. Kittredge also

mentioned two prospective routes beyond Sun Notch, with a decision

needed about whether to bypass Park Headquarters and go to Rim Village

by way of Garfield Peak instead. One route that did just that came to be

known as the "high line." The other route, a "low line," largely

utilized the existing road connecting Lost Creek to Vidae

Falls.

Andesite boulders quarried

at the base of the Watchman during the 1930s became a

conspicuous part of designed cultural landscapes at Rim

Village, Park Headquarters, and along Rim Drive.

|

With segment 7-A scheduled for bid in the fall

of 1930, the next phase of location work focused on it. Resident BPR

engineer John R. Sargent took charge of the L-line survey for the

initial part of Rim Drive after NPS landscape architect Merel Sager

found the P-line unsatisfactory in "numerous" places. Sager effected

revision of the old line with advice from Merriam, Harold C. Bryant

(assistant director of the NPS as head of the branch of research and

education in the Washington Office), and Bryant's deputy, geologist

Wallace W. Atwood. Sager and Vint went over the revised line with

Sargent in August, with Sager returning in October to meet with Sargent

about designating certain places along segment 7-A with Class B

excavation. Clearing by NPS crews under BPR supervision commenced

shortly thereafter as a way to allow the prospective grading contractor

the benefit of a full working season in 1931.

L-line surveys continued over the following

summer and proceeded quickly enough over segments 7-B and 7-C for the

NPS to pre-advertise bidding on them in November 1931. The location

work covered a new road of just over 13 miles, one now routed almost to

the base of Mount Scott. This line avoided the 10 to 12 percent grades

on the old Rim Road's ascent of Cloudcap through use of a dead-end spur

road to the top. After some discussion, the NPS chose a line having a

gentler grade routed away from the rim down to the Cottage Rocks

viewpoint, instead of going down the south face of Cloudcap. The

portion of segment 7-C between Cloudcap and Kerr Notch then became known

as 7-C1 and subsequently divided into two grading contracts, units 1 and

2.

Park Superintendent David Canfield could thus

confidently assert by November 1934 that the award of two grading

contracts in 7-C1 brought the Rim Drive three-quarters of the way around

the caldera. Anticipated construction, Canfield noted, would provide

the planned connection with the East Entrance and U.S. 97, leaving only

a quarter of the circuit "untouched" except for survey work. Location

of that remaining quarter became contentious, beginning with a salvo

launched in May 1931 by Park Commissioner William Gladstone Steel. He

wanted a road built from the base of Kerr Notch to Crater Lake Lodge

inside the caldera at a 4 percent grade, a route to be accompanied by a

tunnel leading to the water. Horace Albright, now director of the NPS,

dismissed the idea as "chimerical." Bryant wrote to Steel and attempted

to point out that the new road's alignment was aimed at preventing it

from being visible at a distance to those standing on the

rim.

In any event, Sager pointed to a pair of big

problems associated with any "high line" route proposed for connecting

Sun Notch with Rim Village, starting with the outlay needed for

obliterating scars on the sides of Garfield Peak. He also called the

construction of a tunnel proposed by BPR "inadvisable," owing to the

prevailing rock types on the ridge above Crater Lake Lodge. Albright

intended to study the high line in relation to the low line favored by

Sager and other landscape architects in July 1931 as part of his stop to

attend the dedication of the Sinnott Memorial. The director ran out of

time to make a field inspection of segment 7-E on that visit to the

park, then deferred a decision on it, finally decideding not to build a

road into Sun Notch by the end of June 1933. Albright wrote to Solinsky

on his last day as director in August and ordered that a "primitive

area," a roadless tract prohibiting vehicular access, be shown on master

plans for the lands north of the old Rim Road between Lost Creek and

Park Headquarters.

BPR engineers, and Sargent in particular, did

not easily give up on the high line. Sargent persuaded Lange and the

new superintendent, David Canfield, to walk the surveyed line of roughly

3 miles between Sun Notch and the lodge in July 1935. Lange went into

considerable detail about the many construction and landscape problems

posed by going through with the high line project in a memorandum to the

NPS office of plans and design in San Francisco. He also pointed to the

face of Dutton Cliff in segment 7-D as offering the "outstanding"

problem, since the road location through large slides of loose rock

would be difficult to camouflage. To put a road into Sun Notch around

Dutton Ridge struck him as contrary to the park idea of "preserving

those areas which are worthy of protection and keeping out any possible

development." Dutton Ridge in particular seemed to Lange to be a

"spectacular creation," while the primitive area around it gave him the

impression that he was the first person to visit. He concluded the

memorandum with a plea to keep any road at least several hundred feet

below the rim at Sun Notch in the event that the higher line of segment

7-D won out over the low line.

Kittredge and the resident NPS engineer,

William E. Robertson, also walked the high line within days of Lange's

field trip. They did so in response to a news article appearing in a

Portland paper that came in the wake of Concessionaire Richard W. Price

taking his case for the high line to the chamber of commerce in Klamath

Falls. The local congressman contacted Secretary of the Interior Harold

Ickes at roughly the same time, and Ickes then referred the query to NPS

director Arno B. Cammerer. Albright's successor dispatched Associate

Director Arthur Demaray to Crater Lake for an on-site inspection of the

two road locations, and told Ickes that the matter would receive further

consideration upon Demaray's return to Washington. Kittredge's

assessment of the high line from Sun Notch to Rim Village focused on the

impact to Garfield Peak, though he offered the possibility of two

one-way roads traversing the cliff face in line with Frederick Law

Olmsted's recommendation for that type of construction "for certain

places."

In his reply to Kittredge, Demaray dismissed

the high line location for 7-E due to its impact on Garfield Peak. He

told Kittredge that further consideration should be given to the high

line in 7-D, one that ran "from Kerr Notch around Dutton Ridge to Sun

Meadows, then joining the present road [from Lost Creek] at the Vidae

Falls. This amounted to a "combination line," one that Canfield

strongly supported when he asked Cammerer to transfer funds originally

programmed for the low line route and instead put them toward building

segment 7-D. Lange again warned that such a road would "deface and

permanently injure" the cliffs of Dutton Ridge, though he injected some

levity into the situation by offering BPR the paraphrase "You take the

high line and I'll take the low line," sung to the tune of "Loch

Lomond."

Vidae Falls.

|

Cammerer went ahead with recommending the

"combination line" of a high 7-D and a low 7-E to Ickes on November 16,

1935. The secretary approved it several weeks later and his office

issued a press release to that effect. Sargent confidently anticipated

the decision by completing the fieldwork for what he called the "final

located line" between Kerr Notch and Vidae Falls by late October, so

that plans could be completed over the winter. Engineers estimated this

stretch of 5.5 miles as the most time consuming portion of Rim Drive to

build, so BPR divided it into three units (as 7-D1, 7-D2, and 7-E1) for

the purposes of bids on future grading contracts. Sargent also ran a

P-line of 4.3 miles for the last segment of Rim Drive, one connecting

Vidae Falls with Park Headquarters, in the fall of 1935. His successor,

Wendell C. Struble, revised the line over the following summer to

eliminate about a mile of road construction, mainly because he and Lange

agreed that the new line effectively reduced the scar width of 7-E2 as

seen from Crater Lake Lodge.

The problem of how to approach Vidae Falls

from Sun Notch and then cross the creek remained since, as Vint pointed

out, Sargent's line came too close to the falls and made any road

crossing involving a fill too noticeable. He recommended that the line

follow an approach road down to the proposed Sun Creek Campground (a

development aimed at the interfluve between Vidae and Sun creeks near

the old Rim Road), so that any fill used to span Vidae Creek might then

be less obvious. A higher location required a bridge, Vint noted, one

preferably built of logs. Canfield questioned the cost in relation to an

expected life of fifteen years, while also suggesting some revisions to

a design used for the log bridge built over Goodbye Creek (located south

of Park Headquarters) in 1929.

Resolution to the Vidae Falls dilemma did not

come until January 1938, after Cammerer wrote to Canfield's successor,

Ernest P. Leavitt. Not only did he want the new superintendent's views

on the controversial location of segment 7-D, but also he took that

opportunity to express a preference for a bridge at Vidae Falls.

Leavitt responded with rather emphatic reasons for why the line from

Kerr Notch to Vidae Falls constituted a serious mistake, then gave

Cammerer a number of reasons why a fill made better sense than a bridge

at the falls. Demaray informed Leavitt in January 1938 that a fill had

been approved, largely due to the "depleted condition" of funds for

roads and trails during the current fiscal year and the small allotment

anticipated for 1939. At this point the associate director regarded any

lingering questions over the location of Rim Drive as "closed," since a

contract for grading 7-E2 had been awarded the previous fall.

|