|

Cumberland Island National Seashore Georgia |

|

NPS photo | |

Forests so quiet that you can hear yourself breathe, sunlight filtered and diffused through over-arching trees and vines, sounds of small animals scurrying in the underbrush, the gentle splash of water moving through the salt marsh, the courting bellow of the alligator; blinding light on water and sand as you emerge from the shadows of the live oak forest, a standing row of slave cabin chimneys, fallow gardens and crumbling walls of mansions from bygone eras. This is Cumberland Island, Georgia's largest and southernmost barrier island and today protected as a national seashore.

The word "seashore" is misleading, for Cumberland Island is a complex ecological system of interdependent animal and plant communities. Each lends itself to the preservation of the other. A system of foredunes protects the interdune meadow and shrub thickets. A canopy of live oak trees stretches out just beyond the back dunes that provide protection from the salt spray, in central and northern sections of the island, pine trees tower over hardwood forests. On the western side of the island, saltwater marshes pulse with the tidal flow. Because the previous owners maintained Cumberland Island in its natural state, nature still reigns on this land that bears the imprint of humankind.

Saltwater marsh

The marshes come into view first as you approach the island from St. Marys, Ga. When the tide is out, the marsh appears like a broad plain of tall grasses intricately interwoven with tidal creeks. Closer examination reveals an array of birds wading through the grass or feeding at the banks of the creeks. Fiddler crabs scurry across mud flats and eat decaying vegetation and other organic material. Raccoons and other animals come down from the uplands to feed on crabs and to search for shellfish.

When the tide is in, the tops of grasses sway with the current, making it hard to distinguish between grass and water, the color of one intensifying the color of the other. These tides play a vital role in the life of the marsh, for on their flood cycle they bring the microscopic organisms that many creatures need for nourishment and the water from which to draw oxygen. On their ebb, the tides flush the silt and debris washed into the marsh from the inland rivers out to sea. The marshes buffer the landward side of the island from the twice daily influx of tidal flow and absorb some of the impact of storms. Marshes possess quiet, changeable beauty, yet they are the most productive land, acre per acre, on the planet. With their wealth of nutrients, marshes support large populations of fish, shellfish, plants, and birdlife. They also act as nurseries. In the grasses and shallow waters here the young of many species begin their lives protected from predators.

Maritime forest

As the marshlands become higher and drier, washed only at extremely high tides, the salt-tolerant communities give way to freshwater-loving plants and then, finally, to trees. The most striking feature of the live oak forest is the solitude. Even the air seems to move noiselessly above the tops of the trees' arching branches. The sounds of an ordinary rainshower are muted by the dense canopy of leaves and vines. Cradled in the branches, resurrection ferns spring up with this life-giving moisture. Draping Spanish moss lends a touch of the exotic as it sways in the breeze. Vivid plumages of painted buntings, summer tanagers, cardinals, and pileated woodpeckers add splashes of color to the somber hues of the forest while the clear notes of yellow-throated warblers and Carolina wrens punctuate the stillness.

Deeper in the forest's shadows at midday, or in interdune meadows at dusk, you may catch fleeting images of the island's white-tailed deer. Raccoons, masked bandits of the forest, are often seen as they tour the island on nightly forays. You may come across a shy and newly arrived resident the armadillo, first seen on the island in 1974. Interdune meadows, both wet and dry, mark the forest's eastern edge. The sand and grass give way to the realm of dunes and beach. Farther inland, freshwater ponds appear like jewels. Here on a warm spring night you can hear the booming of the bull alligator as it goes through its courtship rites. Rainfall sustains the ponds and the wildlife that are drawn to them, adding yet another dimension to the island.

Beach

Emerging from the darkness of the forest to the brightness of the beach you momentarily lose your sight, so sudden is the change. On the beach the waters rise and fall twice daily, washing to and fro over the sand, shaping and rearranging. The wind, too, plays a role in this process. Barrier islands appear to be permanent, but actually they are continually in the process of change. In some areas on Cumberland Island, you may notice the dunes covering the shrubs and trees in their path. The plants that grow on the dunes are the stabilizing element. Their root systems are fragile and are affected by the impact of humans and animals. Overgrazing by the island's feral horses may impair the ability of some grasses to Least tern reproduce.

Here the shorebirds are given to the spirit of movement. Sandpipers dance before the rhythmic advance and retreat of the water, and gulls soar on the ocean breeze. An osprey may dive into a wave before your eyes and a few seconds later emerge with a mullet in its talons. Loggerhead turtles, ancient reptiles of the sea, lumber ashore on deserted island beaches at night. Guided by instinct, they lay their eggs and then return to the sea. Hatchlings emerge about 60 days later and scurry for the protection of the surf. Today tracks of humans, birds, and other animals mark the beach. Tomorrow they will have been swept away, and the beach will take on new configurations.

The Human Imprint

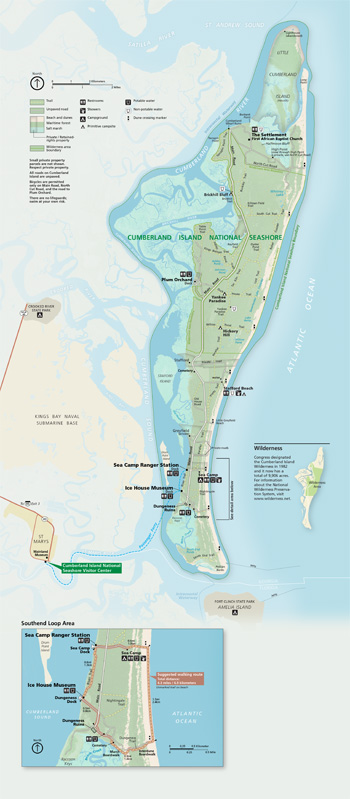

(click for larger map) |

For thousands of years people have lived on Cumberland Island, but never in such numbers as to permanently alter the character of the landscape. Piles of shells, called middens, provide us with clues to the lives of the Indians who left them. An occasional pot shard indicates that Spanish soldiers and missionaries were here in the mid-1500s. No signs remain of Fort William and Fort St. Andrews, built to protect British interests. Revolutionary War hero Gen. Nathanael Greene purchased land on Cumberland Island in 1783. His widow, Catherine Greene, constructed a four-story tabby home that she named Dungeness. In the 1890s, The Settlement was established for black workers.

The First African Baptist Church, established in 1893 and rebuilt in the 1930s, is one of the few remaining structures of this community. Thomas Carnegie, brother and partner of the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, began building, with his wife Lucy, on Dungeness's foundations in 1884. The ruins of this mansion remain today. Plum Orchard, an 1898 Georgian Revival mansion built for son George and his wife Margaret Thaw, was donated to the National Park Foundation by Carnegie family members in 1971. Their contribution, as well as funds from supporting foundations, helped win Congressional approval for Cumberland Island National Seashore.

Enjoying Cumberland Island

Ferry Information A passenger ferry serves Cumberland Island from St. Marys daily except December through February, when it does not run on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. It does not carry cars, bicycles, kayaks, or pets. It departs the mainland at 9:00 and 11:45 a.m. and the island at 10:15 a.m. and 4:45 p.m. From March through September it also departs the island at 2:45 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday. Ferry reservations may be made up to six months in advance. If you miss the last ferry departing the island, you must charter a boat for the return trip.

Fees and Supplies Fees are charged for ferry service, entrance to Cumberland Island, and camping. No supplies are available on the island. You must bring all your supplies with you. There is drinking water at the visitor center, museum, ranger station, and Sea Camp Beach campground. Walking shoes and rain gear are recommended.

Camping All camping is limited to seven days. The developed campground at Sea Camp Beach has restrooms, cold showers, and drinking water. Campfires are permitted at Sea Camp, but only dead-and-down wood may be used. No backcountry sites—Brickhill Bluff, Yankee Paradise, or Hickory Hill—have any facilities. Backcountry campsites have wells nearby; the water must be treated. Campfires are not permitted, so bring portable stoves. Both a camping permit and a reservation are required. Get permits at the Sea Camp Ranger Station.

Fishing Georgia state fishing laws apply.

Weather Cumberland Island winters are short and mild. Summer temperatures range from the 80s°F to the low 90s. In summer it is best to visit the beach early or late in the day and to find shade in the hot, midday hours.

Private Property Some of Cumberland Island is privately owned. Respect the rights of landowners and do not trespass.

Safety The Dungeness ruins and outbuildings are closed to the public. They are unstable and unsafe, and diamondback rattlesnakes, one of three poisonous snakes here, live in the ruins. • Check yourself often and carefully for ticks, which carry Lyme disease. • There are no lifeguards. • During periodic managed hunts the wilderness area is closed to the public. • Don't approach feral horses; they are dangerous and kick and bite. Feeding any wildlife is both prohibited and dangerous.

Source: NPS Brochure (2012)

|

Establishment Cumberland Island National Seashore — October 23, 1972 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

An Ecological Survey of the Coastal Region of Georgia (HTML edition) (A. Sydney Johnson, Hilburn O. Hillestad, Sheryl Fanning Shanholtzer and G. Frederick Shanholtzer, 1974)

Assessment of Estuarine Water Quality at Cumberland Island National Seashore, 2007 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2010/121 (M. Brian Gregory, Joe DeVivo, Phillip H. Flournoy and Katy Austin Smith, December 2010)

Atlantic National Seashores in Peril: The Threats of Climate Disruption (Stephen Saunders, Tom Easley, Dan Findlay and Kathryn Durdy, ©The Rocky Mountain Climate Organization and Natural Resources Defense Council, August 2012, all rights reserved)

Coastal Hazards & Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment for Cumberland Island National Seashore: Summary of Results NPS 640/186744 (K.M. Peek, H.L. Thompson, B.R. Tormey and R.S. Young, November 2022)

Coastal Vulnerability Assessment of Cumberland Island National Seashore (CUIS) to Sea-Level Rise USGS Open-File Report 2004-1196 (Elizabeth A. Pendleton, E. Robert Thieler and S. Jeffress Williams, 2004)

Condition Assessment Report: Historic Plantation Slave Community Chimneys, Cumberland Island National Seashore (September 12, 2003)

Cultural Landscape Report: Dungeness Historic District, Cumberland Island National Seashore (Susan Hitchcock, July 2007)

Cumberland Island National Seashore: A History of Conservation Conflict (Lary M. Dilsaver, ©Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, 2004. All rights reserved.)

Cumberland Island: a place apart: Natural History Handbook (Valerie Thom, 1977)

Effects of Disturbance on Community Boundary Dynamics of Cumberland Island, Georgia (Guy R. McPherson and Susan P. Bratton, from Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceeding, Vol. 17, 1991)

Foundation Document, Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia (February 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia (February 2014)

Geologic Guide to Cumberland Island National Seashore Georgia Geologic Survey Geologic Guide 6 (Martha M. Griffin, 1982)

Historic Resource Study, Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia and Historic Structure Report, Historical Data Section of the Dungeness Area (Louis Torres, October 1977)

Historic Structure Report: The Grange Residence of William Page Including Notes on the Beach Creek Dock House and Pump House, Cumberland Island National Seashore (GWWPO, Inc./Architects, September 2014)

Lands Legacy Tour, Cumberland Island National Seashore: Fall 2012 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR-2013/695 (Lena Le, July 2013)

Marine Vulnerability Assessment of Cumberland Island National Seashore NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CUIS/NRR-2016/1281 (Katie McDowell Peek, Andy Coburn, Emily Stafford, Blair Tormey, Robert S. Young, Holli Thompson, Laura Bennett and Alicia Fowler, August 2016)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Duck House (undated)

High Point-Half Moon Bluff Historic District (Martin's Half Moon Bluff Tract/High Point) (Lou Torres, John Ehrenhard and Len Brown, January 1978)

Main Road (undated)

Boundaries of Cumberland Island National Seashore as Defined by Congress (Ann Huston and Lenard Brown, November 1983)

Dungeness Historic District Partial Listing (undated)

Plum Orchard Historic Distrct Partial Listing (undated)

Rayfield Archeological District Partial Listing (undated)

Stafford Plantation Historic District Partial Listing (undated)

Table Point Archeological District Partial Listing (undated)

Newsletter: Land Exchange, Cumberland Island National Seashore (September 2024)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Cumberland Island National Seashore NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CUIS/NRR-2018/1773 (Kathy Allen, Andy J. Nadeau and Andy Robertson, October 2018)

Park Newspaper (The Mullet Wrapper): Spring 2006 • Jun-Aug 2006 • Sep-Nov 2006 • Dec-Feb 2007 • Sep-Jan 2008 • Mar-May 2009 • Sep-Nov 2010 • Dec-Feb 2011 • Mar-May 2011 • Dec-Feb 2012

Shoreline Change at Cumberland Island National Seashore: 2018-2019 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2020/1258 (Lisa Cowart Baron, February 2020)

Terrestrial Vegetation Monitoring at Cumberland Island National Seashore: 2020 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2022/1365 (M. Forbes Boyle and Elizabeth Rico, September 2022)

The San Pedro Mission Village on Cumberland Island, Georgia (Carolyn Rock, extract from Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective, Vol 15 No. 1, 2011)

Underground Storage Tank Initial Site Characterization, Cumberland Island National Seashore, St. Marys, Georgia NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-90/01 (Gary W. Rosenlieb, October 1990)

Vegetation Mapping at Cumberland Island National Seashore NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR-2017/1511 (Rachel H. McManamay, September 2017)

Visitor Use Management Plan and Environmental Assessment, Cumberland Island National Seashore (November 2022)

Visitor Use Study: 2010-2011, Cumberland Island National Seashore Phase II Results (Jeffrey C. Hallo, Robert E. Manning, Matthew T.J. Brownlee and Brandi L. Smith, March 2012)

Vulnerability of National Park Service Beaches to Inundation during a Direct Hurricane Landfall: Cumberland Island National Seashore U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2007-1387 (Hilary F. Stockdon, David M. Thompson and Laura A. Fauver, October 2007)

cuis/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025