|

Fort Larned National Historic Site Kansas |

|

NPS photo | |

Visited and inspected the new buildings finished and in process at the Post. They are all of stone, and are really fine structures.

—Albert Barnitz, Capt. 7th US Cavalry, 1868

At Fort Larned, which lies just steps from the Santa Fe Trail, cultures mixed every day. Soldiers met Plains Indians, European American and Hispanic teamsters, homesteaders, hide hunters, scouts, and railroad workers. US Army regulars served with paroled Confederates. The fort housed African Americans later known as Buffalo Soldiers, who formed Company A of the 10th Cavalry.

The post evolved from a rough, temporary camp set up in 1859 to guard the construction of an adobe mail station. It was a bustling soldier town by 1867 but became a near ghost town by 1878. The soldiers' primary purpose was to escort mail coaches and military supply wagons on the trail. Their broader mission was to keep the peace on the plains—and take action when required.

The fort also hosted Indian agents for the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Plains Apache, Kiowa, and Comanche tribes. In 1867, peace commissioners appointed by Congress met at Fort Larned to plan the Medicine Lodge treaties.

A huge American flag flew atop a 100-foot pole at the parade ground center. Many travelers saw the flag as a beacon of strength and security, but for the Plains Indians it symbolized lost freedom.

Reshaping Landscapes and Nations

After the 1680s, when Plains Indians first mounted horses, tribes including the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Plains Apache, Lakota, Kiowa, and Comanche moved across the region in pursuit of bison. The animal provided for their material culture—skins for tipis, clothing, and trade, bone for tools—and food for sustenance. By the 1860s, a stream of newcomers and changing US government policies limited the tribes' access to the bison herds and imposed strict boundaries. Commerce, aided by the US Army, had become an agent of change.

Boundaries

Plains Indian Tribes divided into two groups north and south of the Arkansas River. They fought for control of the grasses—to feed their horses—and bison herds until 1840, when they reached a peace. The Santa Fe Trail followed the same river that had served as boundary for the two groups. The river also formed Mexico's northern border until 1848.

I don't want to settle. I love to roam all over the prairies. There I feel free and happy, but when we settle down we grow pale and die.

—Kiowa chief, Satanta, 1867

Freedom

At the Medicine Lodge peace negotiations Satanta explained why his people should not be "concentrated" on reservations. By 1871, urged on by the military, Congress abandoned diplomacy and gave the tribes a stark choice, annihilation or the reservations.

Power

The idea of manifest destiny, that God intended the nation "to possess the whole of the continent." was a justification for the US-Mexico War, 1846-48.

Economy

International Trade Routes

The Santa Fe Trail linked suppliers in the American West with traders in

New York. New Orleans, and European cities. Kiowa leader Satanta grew

wealthy as a supplier of bison hides.

Abundance

As late as the 1860s many people saw the bison as an endless resource. Plains Indian stories tell of the herds' origin in caves or below lakes from which they "swarmed, like bees from a hive." Hide hunters, encouraged by the US Army, harvested the bison to the point of near extinction. Bison bones thickly littered the prairies. In 1884 the last rail shipment of hides left the plains. Demand had exceeded supply.

Trade

Santa Fe Trail Some goods shipped west along the Santa Fe Trail continued south to Chihuahua and Sonora along the Camino Real. Eastbound goods included gold, silver, donkeys, mules, furs, and wool. The Spanish dollar was legal tender in the US until 1857.

Culture

Plains Indian Art after the 1860s

While imprisoned at Fort Marion, Florida, from 1874 to 1878, Plains

Indians made drawings on paper. Before the 1860s they would have painted

on bison hide.

The new nation expands west.

By 1821 an overland trade route links Missouri and the Mexican city of

Santa Fe. The route crosses "open country" where Plains Indians live

and hunt.

1821 Mexico wins independence from Spain. Missouri becomes a state. Santa Fe Trail opens. Trade flows via the 900-mile-long trail between Missouri and Santa Fe and south to Chihuahua and Sonora. Traders call it the Mexican or Santa Fe Road.

1824 US Secretary of War establishes the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The goal is to manage US relations with Indian tribes.

1830 President Andrew Jackson signs the Indian Removal Act. It forces Indians from lands east of the Mississippi River to western areas including present-day Kansas and Oklahoma. The act establishes a legal precedent for removal and launches decades of treaty making.

1834 Indian Trade and Intercourse Act. The act loosely defines Indian Country, which includes the future state of Kansas.

1836 Republic of Texas proclaims independence from Mexico.

1845 US annexes Republic of Texas. Mexico severs diplomatic relations, asserts ownership of annexed land between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers.

1846 US declares war on Mexico.

1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. Mexico cedes over half its territory to the US. The cession includes all or portions of Texas, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, California, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Oklahoma, and Kansas.

1854 Kansas Territory established, opens Indian Country to European American settlers and increases need for military presence in the region.

Santa Fe Trail traffic increases.

The US Army must protect the flow of military supplies, the mail,

commerce, and emigrants along the trail, even as it fights the Civil War.

1859 Colorado Gold Rush. Over 100,000 gold seekers cross the Central Plains, many on the Santa Fe Trail. Many Indians resist the invasion of their hunting grounds and sacred places.

Camp on Pawnee Fork. Set up to guard a US mail station, it soon becomes known as Camp Alert because of constant threats from Kiowas and Comanches.

1860 Fort Larned established when camp is renamed and moved to its present site. By September its population grows to 270 men, housed in rough wood and adobe structures.

1861 Kansas becomes 34th state. Civil War begins.

1862 Congress passes Homestead and Pacific Railway Acts.

Congress invests in the frontier forts.

The military expands its presence along the Santa Fe Trail and other

trade corridors.

1864 Kiowas take over 200 mules and horses from the fort's corrals. Cheyennes attack a store and stage company at Walnut Creek.

US Army awards Hispanic merchant Epifania Aguirre a contract to freight five million pounds of supplies to the frontier forts.

Thirty miles north of Fort Larned, US troops kill Cheyenne peace chief Lean Bear as he proclaims friendship and holds a peace medal that President Lincoln presented to him. Indian attacks and US Army retaliation increase.

Detachments of the 1st and 3rd Regiments, Colorado Volunteer Cavalry, massacre 230 Cheyennes and Arapahos who believe them·selves under US protection at Sand Creek, Colorado Territory.

1865 Civil War ends. Gen. Robert E. Lee surrenders to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox.

1865 Little Arkansas Treaties with Southern Cheyennes, Southern Arapahos, Plains Apaches. Kiowas, and Comanches assign the tribes to reservations in present-day Oklahoma. The Indians keep the right to hunt north of the Arkansas River so long as bison are there.

1866-68 Civilian contractors construct Fort Larned's permanent stone barracks, officers quarters, blockhouse, storehouse, shops, and commissaries.

1867 Kiowa chief Satanta issues warning to Indian Agent Edward Wynkoop's interpreter: "The white man must build no more houses, must burn no more of their wood, must drink no more of their water, must not drive their buffaloes off, and the Santa Fe Line must be stopped."

Peace Commission fails.

The US Army takes charge. Fort Larned provides support for the

resulting campaign against the Indians and hosts key military

officers.

1867 Gen. Winfield Hancock arrives at Fort Larned with 1,400 men. He summons several chiefs from a nearby village to a council at the fort. Fearing an attack, the Indians abandon their village. Hancock sends Lt. Col. George Custer in pursuit and burns the village, setting off Hancock's War. In response, Cheyennes and Lakota attack stage stations, wagon trains, telegraph lines, and railroad camps.

Congress appoints four civilian and three military commissioners, including Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, to a Peace Commission. The aim is to "concentrate" the Plains Indians onto reservations.

Medicine Lodge Treaties. Hundreds of Kiowas, Arapahos, Cheyennes, Plains Apaches, and Comanches meet with the Peace Commission at Medicine Lodge Creek, Kansas. The resulting treaties fail to achieve peace.

1868 Peace Commission is dissolved. Department of War enacts policy of "peace within, war without [the reservations]."

Gen. Philip Sheridan meets with Indian leaders at Fort Larned. Soon after, he launches a new strategy intended "to make [the Plains] tribes poor by the destruction of their stock, and then settle them on lands allotted to them." As part of this campaign, Custer leads an attack on a peaceful Cheyenne village on the Washita River. Peace chief Black Kettle and his wife, Medicine Woman Later, are among those killed.

1871 All treaty making ends.

1872 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad reaches Fort Larned and the western border of Kansas.

1878 Fort Larned is decommissioned.

Touring the Fort

Although Fort Larned is one of the best-preserved western forts, its appearance today belies that of the late 1860s. The many wood and adobe buildings outside the central parade ground (hospital, laundry, stables, mail station, bowling alley, teamsters' quarters, and others) quickly deteriorated and do not survive.

From 1865 to 1868 over 200 civilians labored to complete ten sandstone buildings, boosting the local economy. Nine of these buildings still stand. Construction and the freighting of supplies among the western forts were welcome sources for civilian contracts.

Santa Fe Trail Spanning 900 miles of the Great Plains, the trail offered riches and adventure for some—at the risk of hardship and peril. Many westbound wagons carried military supplies, metal tools, cloth, and alcohol. Other goods included hardware like fish hooks, trade items like cut glass beads, home goods like cookware, and staples like brown Havana sugar and coffee. Some Plains Indians viewed travelers on the trail as trespassers. As clashes grew more frequent, the US government expanded the string of forts along the trail to protect American interests and promote peace.

First Mail Station US Postmaster General Joseph Holt asked the War Department to protect the Pawnee Fork mail station from Indian raids in 1859. The US Army soon arrived and by 1860 began constructing a permanent fort. In 1861 the garrison expanded from 60 to 292 men, but throughout Fort Larned's lifetime its numbers rose and fell. Factors included the US Army's need for troops to fight back east in the Civil War, the intermittent nature of Indian hostilities, and evolving US government policy toward the tribes.

Indian Agency By 1855 two Indian agents had set up offices at Fort Larned—Edward W. Wynkoop for the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes and Jesse Leavenworth for the Kiowa, Plains Apache, and Comanche. In 1868, two days after Lt. Col. George Custer led an attack on a peaceful Cheyenne camp on the Washita River, Wynkoop resigned.

Tribes Tribes visited the Indian agency to collect annuities—including guns, blankets, tools, clothing, coffee, and flour—promised them in the Little Arkansas and Medicine Lodge treaties of 1865 and 1867 in exchange for their lands. Congress intended the annuities to placate the tribes, help them adopt European American ways, and help them adapt to life on the reservations.

Buffalo Soldiers One of the first African American cavalry units of the post-Civil War US Army, Company A, 10th Cavalry, arrived at Fort Larned in April 1867. In late December 1868 after a fight over a billiards game, the cavalry stables burned. Arson was suspected but no witnesses came forward. On the night of the fire, commanding officer Major John Yard had ordered Company A to guard a distant wood pile. Soon after, Yard transferred the unit to Fort Zarah rather than deal with the racial tensions.

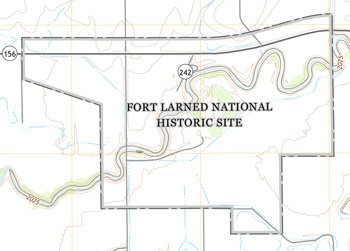

(click for larger maps) |

Visiting Fort Larned

Fort Larned National Historic Site is six miles west of Larned, Kansas, on KS 156. The fort is open daily 8:30 am to 4:30 pm; closed Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1.

Call or check our website for programs and special events throughout the year. You must schedule guided group tours in advance.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to a visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our website.

For Your Safety For a safe visit, use caution and common sense. Please observe all hard hat and other warning signs around buildings undergoing restoration or stabilization. Be alert for uneven ground and non-standard steps. Please keep children a safe distance from the Pawnee River.

For a complete list of regulations including firearms, check the park website.

Emergencies call 911

Help Us Protect the Park

The National Park Service works to stabilize the fort's buildings and

prevent deterioration. We need your help to ensure that future

generations can see the fort as you see it today. Do not disfigure the

fort by scratching, carving, or marking names and initials on walls or

sandstone blocks. Federal laws protect all natural and cultural features

in the park.

Source: NPS Brochure (2017)

|

Establishment Fort Larned National Historic Site — August 31, 1964 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Conflict and Commerce on the Santa Fe Trail: Fort Riley - Fort Larned Road, 1860-1867 (David K. Clapsaddle, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 16 No. 2, Summer 1993)

Cultural Landscape Report: Fort Larned National Historic Site, Kansas (Quinn Evans/Architects & Land and Community Associates, May 1999)

Excavations Inside Historic Structure 4, The New Commissary, at Fort Larned National Historic Site, Kansas Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report No. 6 (Kristin L. Griffin, 1991)

Fort Larned: Garrison on the Central Great Plains (©Timothy Ashley Zwink, PhD Thesis Oklahoma State University, December 1980)

Foundation Document, Fort Larned National Historic Site, Kansas (July 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Fort Larned National Historic Site, Kansas (January 2017)

Geologic Map of Fort Larned National Historic Site (May 2024)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Fort Larned National Historic Site NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2024/125 (Michael Barthelmes, May 2024)

Geophysical Investigations and Archeological Monitoring of the Underground Electric Line Installation Project Area at the Fort Larned National Historic Site, 14PA305, Pawnee County, Kansas Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report No. 136 (Steven L. De Vore and Melissa A. Baier, 2014)

Geophysical Prospection and Archeological Investigations of the Proposed Bridge Replacement, Entrance Road Realignment, and New Visitor Parking Lot Project at the Fort Larned National Historic Site, 14PA305, Pawnee County, Kansas Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report Series No. 132 (Steven L. De Vore and Albert M. LeBeau III, 2012)

Historic American Buildings Survey

Barracks (West) - Fort Larned HABS No. KANS-21

Barracks (East) - Fort Larned HABS No. KANS-22

Blacksmith & Wheelright Shop - Fort Larned HABS No. KANS-23

Bakery & Mess Hall - Fort Larned HABS No. KANS-24

Commissary Storehouse & Stables - Fort Larned HABS No. KANS-25

Quartermaster Storehouse - Fort Larned HABS No. KANS-26

Officer Quarters (South) - Fort Larned HABS No. KANS-27

Commanding Officer Quarters - Fort Larned HABS No. KANS-28

Officer Quarters (North) - Fort Larned HABS No. KANS-29

Historic Furnishing Study, Historical and Archeological Data, Fort Larned National Historic Site, Kansas (John Albright and Douglas D. Scott, August 1974)

Historic Furnishings Report: Commanding Officer's Quarters, HS-8, Fort Larned National Historic Site, Kansas (Mary K. Grassick, 1996)

Historic Furnishings Report: Infantry Barracks HS-2 — Fort Larned National Historic Site (William L. Brown III, 1986)

Historic Furnishings Report: Post Hospital, HS-2, New Commissary, HS-4, Old Commissary Storehouse, HS-5, Quartermaster Storehouse, HS-6, Officers' Quarters, HS-7 — Fort Larned National Historic Site (L. Clifford Soubier and William L. Brown III, 1989)

Historic Structure Report / Historic Furnishing Study: Fort Larned Commanding Officer's Quarters (HS-8) (A. Berle Clemensen, May 1980)

Historic Structure Report: Blockhouse (HS-10), Fort Larned National Historic Site (Ron Cockrell, Alan W. O'Bright and Janis L. Dial, 1991)

Historic Structures Report (Part I), Fort Larned National Historic Site, Kansas (Don Rickey, Jr. and Thomas N. Crellin, April 1967)

Historic Structures Report (Part II), Historical Data Section, Fort Larned National Historic Site (HTML edition) (James W. Sheire, February 1969)

Historic Structure Report (Part II): Barracks Building, HB-1 (Visitor Center), Fort Larned National Historic Site, Pawnee County, Kansas (A. Lewis Koue, December 1971)

Historic Structures Report (Part II): Enlisted Barracks, HB #2, Fort Larned National Historic Site (James Sheire and Charles S. Pope, March 1969)

History of Fort Larned (William Errol Unrau, c1957)

Junior Ranger Program, Fort Larned National Historic Site (2020; for reference purposes only)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Fort Larned National Historic Site (April 2009)

Master Plan: Fort Larned National Historic Site (November 1978)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Fort Larned (c1957)

Fort Larned National Historic Site (David A. Clary, March 18, 1976)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Fort Larned National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SOPN/NRR-2014/866 (Kimberly Struthers, Robert E. Bennetts, Nina Chambers, Patricia Valentine-Darby and Tomye Folts-Zettner, October 2014)

Newsletter: Fort Larned Outpost (Santa Fe Trail Research Site, 1991-2021)

Riparian Condition Assessment for the Pawnee River (Version 2.0), Fort Larned National Historic Site, Kansas NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/WRD/NRR-2016/1246 (Michael Martin and Joel Wagner, July 2016)

The Story of Fort Larned (William E. Unrau, extract from The Kansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 23 No. 3, Autumn 1957, ©Kansas State Historical Society)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Fort Larned National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SOPN/NRTR-2007/072 (Dan Cogan, Lisa M. Castle Walker,, Hillary Loring, Suneeti Jog and Jennifer Delisle, May 2007)

Volunteer Handbook, Fort Larned National Historic Site (2018)

fols/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025