|

Fort McHenry National Monument & Historic Shrine Maryland |

|

NPS photo | |

Francis Scott Key and "The Star-Spangled Banner"

The Battle of Baltimore would be remembered only as one of a few American victories of consequence in the War of 1812 had not Francis Scott Key so effectively dramatized the bombardment, the flag, and much of the feeling of the day in verse.

A week before the battle, Key, an influential young Washington lawyer, set out with Col. John S. Skinner, U.S. Commissioner General of Prisoners, on a mission to the British fleet. They sought the release of a friend. Dr. William Beanes, arrested for allegedly violating a pledge of good conduct after the Battle of Bladensburg outside of Washington. Sailing from Baltimore on September 5, they reached the British fleet in the Chesapeake Bay on September 7, and in a few days of negotiation had arranged for Beanes to go free. But because they had learned of the British plan to attack Baltimore, they were detained until after the assault for fear they would alert the city's defenders.

Key, Colonel Skinner, and Dr. Beanes witnessed the long bombardment from the deck of a U.S. truce ship. Key later described how he felt when he saw McHenry's flag still waving at dawn on the 14th: "Through the clouds of the war the stars of that banner still shone in my view, and I saw the disconfitted host of its assailants driven back in ignominy to their ships. Then, in the hour of delverance, and joyful triumph, my heart spoke; and 'Does not such a country and such defenders of their country deserve a song?' was its question."

Key jotted down notes aboard the truce ship on September 14 and finished the poem upon his return to Baltimore the evening of the 16th. First titled "Defence of Fort McHenry," the poem was published the next day and was soon being sung to the tune of "To Anacreon in Heaven." Now known as "The Star-Spangled Banner," it became the National Anthem of the United States in 1931.

Maj. George Armistead wanted Fort McHenry's flag to be large enough "that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance." The flag he received measured 42 by 30 feet and was made by Mary Pickersgill. That flag is called the "Star-Spangled Banner" because of Francis Scott Key's poem. It is displayed in the Smithsonian Institution's Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

Fort McHenry

The repulse of a British naval attack against this fort in 1814 prevented the capture of Baltimore and inspired Francis Scott Key to write "The Star-Spangled Banner."

From 1793 to 1815 England and France were at war. Intent on crushing each other, both nations confiscated American merchant ships and cargoes in an attempt to prevent supplies from reaching enemy ports, acts many Americans viewed as violations of their rights as neutrals. The situation was made hotter by British impressment of American seamen and the demands of the "War Hawks," a group of southern and western Congressmen who wanted the United States to annex British Canada and Spanish Florida. The declaration of war against England on June 18, 1812, to preserve "Free Trade and Sailors' Rights," was carried by the War Hawks.

For two years the Americans were mostly an annoyance to the British, who could not devote much attention to them until after Napoleon's defeat in April 1814. Then in mid-August a British force of some 5,000 army and navy veterans under the joint command of Maj. Gen. Robert Ross and Vice Adm. Alexander Cochrane sailed up Chesapeake Bay, intent on giving the Americans "a complete drubbing." They did just that at the Battle of Bladensburg and went on to burn Washington. Then they turned their attention to Baltimore.

Baltimore was better prepared for the invaders than Washington had been. Under Maj. Gen. Samuel Smith, a U.S. Senator and veteran of the Revolution, defenses were erected, arms and equipment laid in, and troops trained. In all, Smith's command totaled about 15,000 men, mostly Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia militia, but also a few regular army units and several hundred sailors under Commodore John Rodgers. Fort McHenry, the key to the harbor, was defended by a thousand men. Its guns and those of two batteries along the river's edge dominated the channels leading to the city. A line of gunboats and sunken hulks across the mouth of Northwest Branch also obstructed entry.

On September 12, Ross's troops landed at North Point and marched toward Baltimore. Later that day, Ross was mortally wounded in the opening skirmish of the Battle of North Point. He was replaced by Col. Arthur Brooke, who completed the battle and compelled the Americans to withdraw. The next morning he marched his troops to within two miles of the city and awaited the results of a naval attack before assaulting the Baltimore defenses.

Admiral Cochrane knew that Fort McHenry must be captured or destroyed if the British campaign was to succeed. He attacked the fort at dawn on the 13th, about the time Brooke began his advance. The bombardment lasted for some 25 hours. Maj. George Armistead, Fort McHenry's commander, estimated later that from 1,500 to 1,800 shells and rockets were fired at the fort. At 2 p.m. two shells exploded on the southwest bastion, killing two officers and wounding several gun crew members.

About midnight on September 13, realizing that Fort McHenry would never fall to shelling alone, Cochrane launched a diversionary attack up the Ferry Branch hoping to distract the Americans long enough for Brooke's troops to storm Rodgers' Bastion guarding the east side of the city. In the dark, rainy night, the attack went awry: some of the landing party rowed up the wrong branch, while other barges were detected and driven back by the combined fire of Forts McHenry, Covington, Babcock, and Look-Out. The failure of this sortie dashed British hopes of capturing Baltimore.

The bombships continued the bombardment until 7 a.m. on September 14, then withdrew down the river. As the British sailed away the American soldiers fired the morning gun and hoisted the large flag that would later become known as the "Star-Spangled Banner" while the musicians played "Yankee Doodle." After rendezvousing in Jamaica with another British army, Cochrane's fleet sailed off to invade New Orleans. There on January 8, 1815, outside the city, a superb British army was soundly defeated by a frontier army led by Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson in the last important battle of the War of 1812.

Fort McHenry never again came under enemy fire, although it continued as an active military post for the next 100 years. During the Civil War it was used as a temporary prison for captured Confederate soldiers, southern sympathizers, and political prisoners. From 1917 until 1923, U.S. Army General Hospital No. 2 was located here to serve World War I veterans. In 1925 Congress made Fort McHenry a national park; 14 years later it was redesignated a national monument and historic shrine, the only park in the country to have this double distinction.

"Let the praise, then, if any be due, be given, not to me, who only did what I could not help doing, but to the inspirers of the song!"

—Francis Scott Key

The Defense of Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry's regular garrison in September 1814 was the U.S. Corps of Artillery under the command of Capt. Frederick Evans. On the eve of the battle, only 60 of the 103 "reputable young men" who made up the corps were available for duty. The rest were sick, had deserted, or were under military guard for discipline. During the bombardment, the corps and militia artillerymen manned the guns within Fort McHenry.

In addition to the regular army garrison, the fort was defended by detachments of the First Regiment of Maryland Militia Volunteer Artillery, three companies of citizen-soldiers consisting of the Baltimore Fencibles, commanded by Capt. Joseph H. Nicholson, the Baltimore Independent Artillerists, under the command of Lt. Charles Pennington, and the Washington Artillerists, commanded by Capt. John Berry. These men represented some of Baltimore's most prominent merchants and investors, defending their businesses, homes, and families. Each of them stood to lose a great deal should the British capture the city.

Maj. George Armistead (1780-1818) took command of Fort McHenry in June 1813. Soon after the battle, he was brevetted a lieutenant colonel by President James Madison. But weakened by the months of preparations to defend the city, he died within three years at the age of 38. He is buried in Old St. Paul's Cemetery in downtown Baltimore.

Vice Admiral Sir Alexander F. I. Cochrane (1758-1832) was appointed commander in chief of the North American Station in 1814. During the Chesapeake Campaign he commanded 50 warships.

The fort was primarily defended by cannon firing 18-, 24-, and 36- pound solid iron cannonballs. Fort McHenry's guns were primarily designed to fire in a horizontal arc and because of their limited range had difficulty in reaching the attacking vessels. On the other hand, six of the British ships carried mortars or rockets whose greater range and higher arc allowed projectiles to be dropped over and behind the walls of the fort. Fortunately, they proved to be extremely inaccurate.

The Congreve rocket was a relatively new instrument of war in 1814. HMS Erebus had been specially modified to fire this frightening but inaccurate weapon.

Mortars were used both on land and at sea. The largest ones fired 190 pound projectiles with wooden fuses to explode the charge.

During the battle, detachments from the 12th, 36th, and 38th U.S. Infantry were stationed in the fort's dry moat. These 600 men, under the command of Lt. Col. William Steuart and Maj. Samuel Lane, were ready to repulse any British landing attempts. The 38th U.S. Infantry had served at Forts McHenry and Covington periodically from May 1813 to May 1814. Some detachments served in the Patuxent River campaign during the summer of 1814. The 36th and 38th Regiments had taken part in the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24th, but were forced to retreat when the inexperienced militia they were to support fled "like sheep chased by dogs" when the British advanced and routed the Americans. After they arrived in Baltimore, they were requisitioned by Major Armistead and took post on September 10, 1814, camping on the grounds north of Fort McHenry.

Many of Fort McHenry's 18-, 24-, and 36-pounder cannon were of naval construction—the type used on ships—and manned in part by land-locked sailors from the U.S. Sea Fencibles, the U.S. Chesapeake Flotilla, and three companies of Baltimore militia artillery.

The U.S. Sea Fencibles were organized under the War Department in July 1813 to "be employed as well on land as on water, for the defense of the ports and harbors of the United States." Two companies of sea fencibles, each mustering 107 men, were stationed at Fort McHenry and commanded by Capts. Matthew S. Bunbury and William H. Addison. Trained in the use of artillery and muskets, their pay, uniforms, and rations were dictated by Navy and Army regulations.

The U.S. Chesapeake Flotilla was organized in July 1813 by Commodore Joshua Barney for the defense of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributary waters. A special unit of the Navy Department, these battle-experienced sailors were subject to the direct orders of the Secretary of the Navy only. A total of 500 men took part in Baltimore's defense. At Fort McHenry, a detachment of 60 men under Sailing Master Solomon Rodman helped man the shore batteries.

The Fort Today

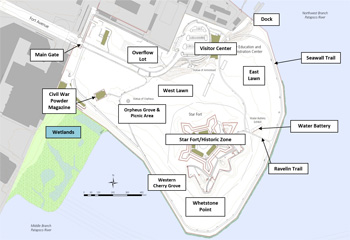

(click for larger map) |

For Your Safety Be alert to potential hazards as you tour the fort and grounds. Particularly hazardous, and therefore prohibited, are climbing on the cannons, statues, exhibits, trees, or the Civil War powder magazines outside the fort. Do not venture too close to the edge of the fort walls, or walk on the seawall. Children must have adult supervision at all times.

Accessibility We are working to make the park accessible to all visitors. Visitors who are mobility-impaired will find curbcuts, ramps, and accessible water fountains, telephones, and restrooms. Walkways in the fort are paved with brick and gravel. The film is captioned, and the theater has an induction loop for visitors who are hearing-impaired.

Printed scripts for the audio stations and electric map are available free in the visitor center. Soundsticks are available for visitors who are sight-impaired.

Activities Park rangers provide interpretive programs daily. Special programs are available for groups that make arrangements at least three weeks in advance. Arrangements are made on a first-come, first-served basis. Information on programs and activities is available at the visitor center.

Defenders' Day, the annual commemoration of the American victory over the British in the Battle of Baltimore on September 12-14, 1814, is celebrated at Fort McHenry every September. For information call the park or check our website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2013)

|

Establishment

Fort McHenry National Monument & Historic Shrine — August 11, 1939 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Master Plan for Fort McHenry National Monument & Historic Shrine (1969)

Administrative History: Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine (Patrick Sullivan, New South Associates, May 14, 2013)

Amendment to the 1968 Master Plan and Environmental Assessment: Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, Maryland (September 1988)

An Architectural Study of Fort McHenry Historic American Building Survey (Lee R. Nelson, January 1961)

Coastal Hazards & Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment for Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine: Summary of Results NPS 346/187361 (B.R. Tormey, K.M. Peek, H.L. Thompson and R.S Young, January 2023)

Cultural Landscape Report for Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine: Site History, Existing Conditions and Analysis Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation (Mark Davison and Eliot Foulds, August 2004)

Development Concept Plan/Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect, Fort McHenry National Monument & Historic Shrine (November 1, 2004)

Early fortifications in Baltimore Harbor (Louis Melchior, April 30, 1925)

Fort McHenry Military Structures: Historic Structures Report, Part I -- Historical Data Section (George J. Svejda, June 30, 1969)

Fort McHenry: Home of the Star-Spangled Banner (1987)

Foundation Document Overview, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, Maryland (January 2016)

Francis Scott Key's Other Verse (William Thomas Sherman)

Furnishings Plan: Star Fort Buildings (Anna Cunningham and Lionel F. Bienvenu, 1965)

Historic Furnishings Report, Historical Data: Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine Draft (John H. McGarry III, 1983)

Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine: Historic Handbook #5 (Harold I. Lessem and George C. Mackenzie, 1954)

Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine: Historic Handbook #5 (HTML edition) (Harold I. Lessem and George C. Mackenzie, 1954, reprint 1961)

Historic Structure Report (Erwin N. Thompson and Robert D. Newcomb, October 1974)

Historic Structure Report, Administrative, Historical and Architectural Data Sections: Seawall, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, Maryland (Sharon A. Brown and Susan Long, August 1986)

Historic Structures Report, Architectural Data Section: Restoration of Basement Kitchen Enlisted Mens' Barracks "E", Fort McHenry National Monument — Part II (Portion) (Norman M. Souder, July 1966)

Historic Structures Report, Historical Data Section: Fort McHenry Military Structures, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, Baltimore, Maryland — Part I (George J. Svejda, June 30, 1969)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine (2016; for reference purposes only)

Masonry Forts of the National Park Service: Special History Study (F. Ross Holland, Jr. and Russell Jones, August 1973)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Fort McHenry (Steven R. Whissen, July 1997)

Newsletter (The McHenry Register/Ramparts): Summer 2009 • Vol. 1 No. 2(1?), May 2011 • Vol. 1 No. 2, July 2011 • Vol. 1 No. 3, September 2011 • Vol. 1 No. 4, November 20111 • Vol. 2 No. 1, January 2012 • Vol. 2 No. 2, March 2012

"On the shore dimly seen...": an Archeological Overview, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, Baltimore, Maryland (Charles D. Cheek, Joseph Balicki and John Pousson, 2000)

Report on Fort McHenry: Statue of Orpheus (George C. Mackenzie, October 28, 1959)

Report on Research for Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine (John C. Moore, September 4, 1957)

Report on Research for Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine (W. Richard Walsh, September 3, 1957)

Research for HARP at The Library of Congress (George C. Mackenzie, May 1, 1958)

Research for HARP at the National Archives (Raymond Ciarrochhi, July 14, 1958)

Research for HARP at the William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Franklin R. Mullaly, April 17, 1958)

Research for HARP in Annapolis, Maryland (Franklin R. Mullaly, January 30, 1958)

The Comprehensive Plan: Fabric Analysis and Treatment Recommendations, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine (Grieves Worrall Wright & O'Hatnick, September 1, 1992)

The history and construction of Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor (Joseph H. Deckman, January 16, 1931)

The History of the Star Spangled Banner from 1814 to the Present (George J. Svejda, February 28, 1969)

The Outworks of Fort McHenry (S. Sydney Bradford, undated)

The Star Fort, September, 1814 (W. Richard Walsh, November 1958)

Uniforms at Fort McHenry, 1814 (George S.A. Carrera, July 1963)

fomc/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025