![]()

MENU

|

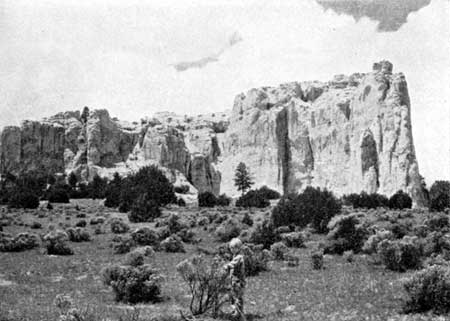

Glimpses of Our National Monuments EL MORRO NATIONAL MONUMENT |

El Morro.

Photo by Grant.

The El Morro National Monument, in west central New Mexico, contains an enormous varicolored sandstone rock rising about 300 feet out of a lava-strewn valley and eroded in such fantastic forms as to give it the appearance of a great castle. On its smooth sides are the inscriptions of five of the early Spanish governors of New Mexico, as well as of many intrepid padres and soldiers who were among the first Europeans to visit this part of the world. Lying as it did on the first highway in New Mexico, the Zuni-Acoma Trail, this rock sheltered as a true fortress many parties whose course took them this way. The shape of the giant monolith is such that an expedition of soldiers could find protection within the cove on the south side, in which was located the water so necessary to the traveler in those days. Here, with a few outguards on the one exposed side, no successful surprise attack could have been made by hostile Indians.

The earliest inscription on the rock is that of Don Juan de Oñate, governor and colonizer of New Mexico, and founder of tIme city of Santa Fe, who in 1606, on his return from a trip to the head of the Gulf of California, passed by El Morro and carved a record of his visit. The inscription of Gov. Manuel de Silva Nieto, who succeeded Oñate, and who took the first missionaries to Hawiku, where a mission was established, reads: "I am the captain-general of the provinces of New Mexico for the King our Lord. Passed by here on return from the towns of Zuni on the 29 of July of the year 1620 and he put them in peace upon their petition, asking him his favor as vassals of his Majesty, and anew they gave their obedience all of which he did with clemency, zeal, and prudence as such most Christian (not plain here) most extraordinary and gallant soldier of unending and praised memory."

The party accompanying Silva Nieto was made up of 400 cavalry and 10 wagons.

"They passed on the 23 of March of 1632 year to the avenging of the death of Father Letrado."—Lujan. Lujan, who signed this inscription, had reference to his trip with other soldiers from the garrison in Santa Fe to Hawiku, where the padre was scalped and murdered by Zuni Indians February 22, 1632, just 100 years before George Washington was born.

The De Vargas inscription of 1692 is of historical importance. Translated it reads, "Here was the General Don Diego de Vargas who conquered for our Holy Faith and Royal Crown all of New Mexico at his own expense year 1692." De Vargas reconquered the Pueblo Indians after their bloody rebellion in 1680 and succeeded in bringing many colonists from Spain to take up homes in this country. He lies buried under the altar of the parish church in Santa Fe.

Lieut. J. H. Simpson, afterwards General Simpson, and the artist, R. H. Kern, were the first Americans to see these inscriptions and bring them to the attention of the public. They visited El Morro and copied the inscriptions in 1849, leaving a record of their own visit on the rock.

The last Spanish inscription, of which there are over 50, was dated 1774. Thus for 168 years El Morro was a regular camping place for parties engaged in maintaining Spanish rule over the Pueblo Indians of this section. Carving of names by present visitors is strictly prohibited, with a heavy fine and imprisonment provided by law for violations, in order that the historic and prehistoric records may be preserved.

Although to Governor Oñate belongs the credit of placing the first Spanish inscriptions on the walls of El Morro, it contains hundreds of Indian glyphs, which were carved many years before the Castilians first camped here. In fact Oñate's inscription was placed over the work of a prehistoric scribe. While these pictographs appear on both sides of the cliff, the best work of the Indians appears on the south side, some of the carvings being so high that it is believed ladders must have been used in making them. These pictographs have never been deciphered, and there is some doubt as to whether they really were intended to tell a story or were merely symbols representing various clans of the Pueblo Indians.

Apparently these pictographs were made by the Indians who lived long ago on top of the mesa and whose ruined terraced homes can be seen there to-day. An ancient carved hand and foot trail used centuries ago by these early inhabitants of New Mexico leads up the side of El Morro from near the water cove. Two other trails, one from the east side of the rock and the other from the west, lead up to the south rim. The trails have been plainly marked, so that travelers to-day may reach the top of the mesa. without difficulty. Some of the old village walls still stand from 4 to 6 feet high.

The lands surrounding inscription Rock were reserved from settlement or entry by order of the Secretary of the Interior June 14, 1901, and on December 8, 1906, shortly after the passage of the antiquities act, the El Morro National Monument was created. June 18, 1917, the monument was enlarged to its present area (240 acres) by the addition of 80 acres containing ruins of archeological interest.

The monument is easily reached from Gallup over a well-posted road which is usually in good condition. Westbound tourists, if they wish, can leave the Santa Fe Railway and National Old Trails Highway at Grants and motor through San Rafael (a strictly Spanish-American settlement of farmers and sheepmen), then on along the foothills of the Zuni Mountains over a road which is posted with signs. Thirty miles from Grants, in a beautiful pine forest, is located the Perpetual Ice Cave. A sign on a pine tree marks the spot of departure for the cave. From here a 400-yard walk takes the visitor to one of the utmost puzzling spectacles in America. Twenty miles farther on one enters El Morro National Monument, where there are inviting places to camp, with a shelter house in case of storm.

From El Morro the road leads to Ramah, 11 miles away. The custodian of the monument is Evon Z. Vogt, who lives at his ranch, 1 mile south of Ramah. From Ramah the traveler can go direct to Gallup, 38 miles, or by an additional 23-mile drive he may visit the famous pueblo of Zuni before going to Gallup over an equally good road.

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs, Oct 19 2000 10:00:00 pm PDT

glimpses2/glimpses10.htm

Top

Top