![]()

MENU

|

Glimpses of Our National Monuments MUIR WOODS NATIONAL MONUMENT |

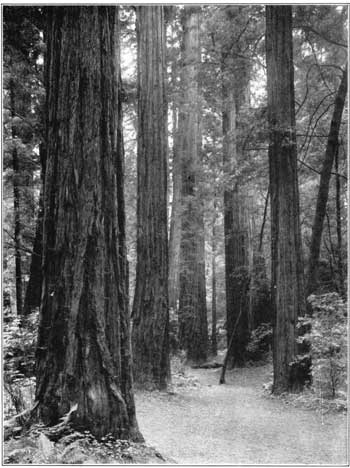

The Redwoods of Muir Woods.

Photo by H. C. Tibbetts.

The Muir Woods, Calif., named in honor of the late John Muir, explorer, naturalist, and writer, was established as a national monument by presidential proclamation of January 9, 1908. The monument was created to preserve a remarkable grove of Sequoia sempervirens, commonly known as redwood trees, on a tract of land containing about 295 acres presented to the Government for this purpose by the late William Kent, ex-member of Congress from California, and his wife, Elizabeth Thacher Kent, of Kentfield, Calif. On September 22, 1921, this acreage was increased by a further gift of 77.90 acres from Mr. Kent, with an additional tract of 50.24 acres donated at the same time by the Mount Tamalpais & Muir Woods Railroad, known the world over for more than a quarter of a century as "the crookedest railroad in the world."

Thus it was that this famous forest, containing trees centuries old, escaped destruction through condemnation proceedings contemplated in 1907 by private interests so that the canyon could be cleared of its priceless timber and the site be utilized for a reservoir for domestic water supply.

This groove of redwoods has grown more beautiful with the years. Thousands of visitors travel each year from far and near to look upon these great trees, which, with their cousins, the Sequoia gigantea, are the greatest and oldest of all living trees. While the latter, commonly called the sequoias, are the larger, the redwoods are unusually graceful and impressive.

The botanical name Sequoia was derived from "Sequoyah," the name of the Cherokee chief who gave the Indians their first alphabet.

Nestling in a sheltered canyon on the lower western slope of Mount Tamalpais, in Marin County, Muir Woods is ideally situated less than a score of miles in a northerly direction from the city of San Francisco, thus affording unusual and easy access for even the most hurried visitor to view these most amazing trees.

Imposing heights are attained by the trees in Muir Woods, many reaching a maximum height of 240 feet. A circumference of 46 feet is not at all rare, nor is a diameter of 15 feet the exception. They vary all the way from tiny sprouts and saplings to mature trees 10 and 15 centuries old.

Devastating fires have marred many of the older trees in the grove. These fires occurred in days long preceding the coming of the white man. Evidences of the ancient fires may be seen even to-day, especially where the older stumps remain standing and the newer generations of young trees have sprouted about the parent root.

The thick, spongy bark of the redwood is peculiarly resistant to flame. Apparently it is almost impossible to destroy totally a mature redwood by burning. A tree badly charred and hollowed by fire at its base is likely to be as green and luxuriant as to foliage and high, green crown as any unharmed sapling of a more fortunate era.

A most persistent quality of the genus is its habit of sprouting from the original root rather than from seed. Although the largest of all the world's trees, the sequoias, strangely enough, bear the smallest seed cone among conifers. In the redwoods, propagation from seed is negligible, the tiny seeds rarely finding conditions ideal enough on the thickly matted floor of a redwood forest to grow from seed. A badly charred stump will immediately lend its underground energy to the sprouting of new trees about the parent stump. This accounts for the circular grouping of individual redwoods usually so characteristic of the species wherever fires or other destructive agencies, such as sawmills, have occurred.

Plant life in Muir Woods is luxuriant—almost exotic. Bay trees grow in profusion, and some fantastic growths abound along the trails. The madrone is plentiful in the loftier, more sunny, boundaries of the canyon, with here and there an isolated California nutmeg tree. There are a number of Douglas firs, some of them formidable in size, the Douglas fir and the redwood being the only two conifers occurring in the park in numbers. In Fern Canyon a Douglas fir 8 feet in diameter has been dedicated to the memory of Mr. Kent.

Many wild flowers have their brief season, including pansies, violets, the strangely spotted deer-tongue, shooting stars, the trillium (coast wake-robin), and a variety of shy blossoms of the wood. Oxalis thrives, a green carpet, about the base of the redwood, pale-pink blossoms adding a bit of color to the spring greenery. Gigantic ferns of several varieties and a thick growth of huckleberry transform the canyon walls and the banks of Sequoia Creek. From May to July the forest is doubly fragrant when the azalea (great western honeysuckle) blooms in abundance. Sweet vernal, or vanilla grass, adds to the fragrance of the trails, especially in the spring and early summer months.

Animal life is plentiful, also. Deer wander freely into the canyon from the upper slopes at dusk and at dawn. They are very tame. Raccoons and wildcats are abundant, and the long blue-gray Douglas squirrels scamper everywhere gathering their winter stores of bay and hazel nuts.

The chatter of blue jays echoes up and down the canyon, their scoldings seldom silenced except at night, and the tiny hummingbird also is found here. There is a singular absence of other birds.

During the spawning season in the winter months salmon trout and steelhead run up Sequoia Canyon. Fishing, however, is strictly prohibited in the Muir Woods National Monument.

Outdoor fireplaces and picnic tables are provided for those who may bring or wish to prepare their lunch. Drinking water is piped throughout the woods. Overnight camping is prohibited, and all visitors must leave before dark. Fires may be built only during daylight hours in the fireplaces provided for such purpose.

Muir Woods may be reached from San Francisco via ferry boat and electric train to Mill Valley, thence by automobile over the Muir Woods Toll Road, a splendid scenic boulevard leading directly to the monument. Cars are not allowed inside the monument, but adequate parking space is provided outside its boundaries.

John B. Herschler is custodian of Muir Woods National Monument, with headquarters at Mill Valley, Calif.

Many people have evinced interest in the correspondence that took place between President Theodore Roosevelt and William Kent regarding the naming of the new monument. This correspondence, which is characteristic of the writers, is quoted below:

THE WHITE HOUSE, WASHINGTON.

MY DEAR MR. KENT: I thank you most heartily for this singularly generous and public-spirited action on your part. All Americans who prize the natural beauties of the country and wish to see them preserved and undamaged, and especially those who realize the literally unique value of the groves of giant trees, must feel that you have conferred a great and lasting benefit upon the whole country.

I have a very great admiration for John Muir; but after all, my dear sir, this is your gift. No other land than that which you give is included in this tract of nearly 300 acres, and I should greatly like to name the monument the Kent Monument, if you will permit it.

Sincerely yours,

THEODORE ROOSEVELT.

To the PRESIDENT,

Washington.MY DEAR MR. ROOSEVELT: I thank you from the bottom of my heart for your message of appreciation, and hope and believe it will strengthen me to go on in an attempt to save more of the precious and vanishing glories of nature for a people too slow of perception.

Your kind suggestion of a change in name is not one that I can accept. So many millions of better people have died forgotten that to stencil one's own name on a benefaction seems to carry with it an implication of mundane immortality as being something purchasable.

I have five good, husky boys that I am trying to bring up to a knowledge of democracy and to a realizing sense of the rights of the "other fellow," doctrines which you, sir, have taught with more vigor and effect than any man in my time. If these boys can not keep the name of Kent alive, I am willing it should be forgotten.

I have this day sent you by mail a few photographs of Muir Woods, and trust that you will believe, before you see the real thing (which I hope will be soon), that our Nation has acquired something worth while.

Yours truly,

WILLIAM KENT.

THE WHITE HOUSE,

Washington.MY DEAR MR. KENT: By George! you are right. It is enough to do the deed and not to desire, as you say, to "stencil one's own name on the benefaction."

Good for you, and for the five boys who are to keep the name of Kent alive! I have four who I hope will do the same thing by the name of Roosevelt. Those are awfully good photos.

Sincerely yours,

THEODORE ROOSEVELT.

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs, Oct 19 2000 10:00:00 pm PDT

glimpses2/glimpses19.htm

Top

Top