|

Guadalupe Mountains

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter V:

MINERAL RIGHTS AND LAND ACQUISITION

Donation of Mineral Rights

During the debates over the Guadalupe Mountains park bill, Congressional committee members worried about the problems inherent in acquiring surface rights to the park lands before the mineral rights. The cost of land acquisition was a fairly firm figure, assuming the purchase took place within a few years. The cost of the mineral rights was an unknown. What if the value of the mineral rights increased unexpectedly? What if the cost to acquire the mineral rights was more than the surface rights? To circumvent these possibilities, the park bill had required that all mineral rights be donated.

More than two years before Congress authorized the park, officials of the Park Service began investigating the ownership of the mineral rights to the Hunter ranch. Their search revealed that J. C. Hunter, Jr., owned the rights to only 1,192.50 acres, the Texas Company (Texaco, Inc.) owned the rights to 25,296.83 acres, and the State of Texas owned the rights to 45,489.55 acres. [1] Hunter agreed to donate his mineral interests. By conveying his surface interests in the 45,489.55 acres to which the State owned the mineral rights, Hunter relinquished his right to act as agent for the State for oil and gas leasing. Under the terms of his agreement with the federal government, however, he retained the right to receive all royalties or rentals payable to him under leases which were in effect at the time of the sale.

In February 1964, Donald E. Lee, Chief of Land and Water Rights for the Park Service, visited Texas to investigate mineral rights for the proposed park. He learned that Texaco's mineral rights consisted of alternating sections in the upper two-thirds of the proposed park. The State of Texas owned the rights to the intervening sections. Most of the State's mineral rights in those sections were not leased. The remainder of the ranch land, in the southern portion of the proposed park, had been leased by Hunter in 1959, 1960, and 1961 (see Figure 13). All leases ran for 10 years and could continue in effect after that time if oil and/or gas were being produced in paying quantities.. [2] Lee estimated the cost to buy out the existing leases and investments to be approximately $450,000. Rather than incur that expense, he recommended that existing leases be allowed to run out if the owners agreed to donate their mineral rights. [3]

Although Lee's estimate of the value of the mineral rights was substantial, others believed it should be even more. As discussed in Chapter IV, during the Congressional hearings Texaco officials took exception to Lee's appraisal, saying it was too low, but they also were unable to provide a more realistic figure. Similarly, the Texas land commissioner argued that relinquishment of the State's mineral rights would deprive the school fund of important real and potential income. The crux of the problem was the speculative nature of the oil and gas industry, making objective evaluation of unexplored resources difficult.

|

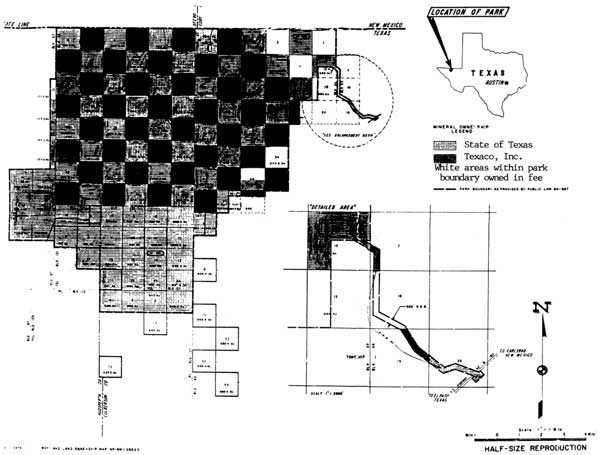

| Figure 13. Mineral rights ownership within Guadalupe Mountains National Park boundaries. The ownership of mineral rights on Hunter's land by the State of Texas and Texaco created a checkerboard pattern. On only a few sections of the designated park lands did the owner of the surface rights also own the mineral rights. Legislation authorizing the establishment of a park mandated that all mineral rights be donated rather than purchased. |

The amendment to the park bill that granted previous owners preferential rights to repurchase their mineral rights if oil and gas production was ever permitted within the park gave Texaco officials and the Texas legislators the security they desired to make donation of their mineral rights feasible. Both Texaco and the State of Texas conveyed their mineral rights to the federal government within a year after the park was authorized. In March 1967, Texas Governor Connally signed the bill approved by the Texas legislature that donated the State's mineral rights on the Hunter ranch. The legislature reimbursed the school fund $5 per acre (approximately $230,000) for the loss of income-producing rights. [4] In a formal ceremony on November 16, 1967, Connally gave the hand-lettered quitclaim deed to Interior Secretary Stewart Udall. On November 2, 1967, Texaco division manager Joe Markley transferred the company's subsurface rights to the federal government. [5]

Acquisition of the J. C. Hunter, Jr., Land

Once Texaco and the State of Texas had donated their mineral rights to the Government, acquisition of surface rights began. According to the Offer to Sell Real Property executed by J. C. and Mary Hunter on August 26, 1966, the federal government had an 18-month option, expiring February 26, 1968, to buy Hunter's 71,978 acres for $1,500,000. Hunter hoped to complete the sale by June 30, 1968, and was reluctant to hold his price any longer than that. [6]

The first Congressional appropriation for land acquisition for Guadalupe Mountains National Park was only $280,000, considerably less than Hunter's sale price. In October 1967, Thomas Kornelis, Chief of Land and Water Rights for the San Francisco Service Center, began negotiating with Hunter about buying his land in two or three parcels. Hoping to make the best possible use of the $280,000 appropriation, Kornelis and Howard Cameron, a Park Service Realty Specialist, proposed using the appropriation to purchase Hunter's tracts of land outside the park boundary, tracts that had been authorized by the park bill to be used as exchange property. These tracts would then be offered to the landowners who held smaller pieces of property within the park boundary. Assuming everyone was willing to accept an exchange, the federal government then would have only one landowner, J. C. Hunter, Jr. to tie to a firm price. [7]

Hunter realized nothing could be done to avert the piecemeal sale of his property, but he sought to protect his interests in some way. Refusing to sell any but the least desirable portions of his property first--the western and southernmost sections--he also asked that no negotiations be made with the smaller landowners until the government actually owned the lands that would be exchanged. [8] Hunter's requests were met. In February 1968, Hunter deeded 14,007.6 acres of his property to the federal government for $280,000. Except for two sections on the northern boundary of the park, which were adjacent to the Pratt donation, the land was all on the west side of the Guadalupes.

Appropriations for the fiscal year of 1969 were even less than before. The House Appropriations Committee vetoed any funding whatsoever, but Senator Yarborough managed to convince the Senate committee to appropriate $205,000, an amount with which the House eventually concurred. Kornelis again approached Hunter and once again Hunter refused to sell any land but sections on the west side, south of the previous tract. However, he agreed to sign a contract for the purchase of the remainder of the property contingent upon the availability of funds in 1970. In May 1969, for $205,000, Hunter conveyed to the federal government an additional 9,773.25 acres of the ranch. At the time of this transaction, Hunter gave immediate possession of the tract to the Park Service, but he reserved a six-month period of possession after the sale of the remaining tract in order to allow his long-time foreman and ranch resident, Noel Kincaid, to move his ranching business. [9]

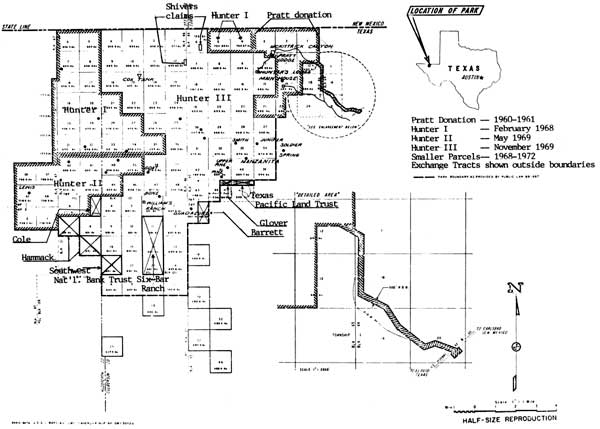

A special appropriation from the general fund of the Interior Department made possible the acquisition of the third tract of Hunter's land. Hunter deeded the final 48,290.55 acres of his ranch to the government on November 20, 1969, for $1,015,000. The sections of land outside the park boundary to be used for exchange with other landowners were a part of this transaction. On December 10, 1969, in a letter to Neal Guse, Superintendent of Carlsbad Caverns, Hunter acknowledged receipt of the final payment for his property and waived his six-month right of possession, stating that Kincaid was no longer in his employ. [10] The government acquired the Guadalupe Mountain Ranch, 72,071.40 acres comprising more than 90 percent of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, for a total of $1,500,000. Figure 14 summarizes the Hunter acquisitions and shows the other individual tracts in the park.

|

| Figure 14. Land ownership within the boundaries of Guadalupe Mountains National Park. When the first Congressional appropriations for land acquisition were small, J.C. Hunter, Jr., protected his interests by selling the least desirable portions of his property first. The map shows the sequence of purchases from Hunter as well as the parcels belonging to other landowners with whom the Park Service had to negotiate. |

Acquisition of Smaller Tracts within the Park Boundaries

After the Hunter acquisition was complete, eight landowners held a total of 4,574 acres within the park boundaries. The hopes of Kornelis and Cameron for a quick and easy exchange for equal amounts of land outside the park boundaries were not fulfilled. Although three landowners were offered a land exchange, only one accepted.

As early as January 1964, the Park Service had begun inquiring about the small landowners involved in the proposed park. In response to a request from Robert Barrel of the Southwest Regional Office, Glenn Biggs outlined the situation with six of the landowners, using information provided by Noel Kincaid:

1. The Ed Hammack property, Sections 7 and 17, Public School Land (PSL) Block 121, contained three wells, the only water source for Hammack's ranching operation. Biggs recommended that these sections not be included in the proposed park.

2. The F. G. Barrett property, the east half of Section 6, Block 65, Township 1, Culberson County was leased to Walter Glover. It contained a water source that provided water to other sections leased or owned by Glover.

3. The Walter Glover property, approximately 86 acres, located in the northeast corner of Section 44, Block 65, Township 1, Culberson County contained two wells, which provided water for domestic as well as livestock use. The property also contained parts of the Butterfield stage station, which once stood at Pine Springs; the Glovers' residence; and a combination country store and cafe that they had operated since 1928.

4. The Southwest National Bank Trust of El Paso owned Section 21, Block 121, PSL, Culberson County. Biggs suggested a trade might be made for land in either of two nearby sections that were adjacent to other property owned by the Trust.

5. The Six-Bar Ranch owned Sections 11, 14, and 23 in PSL Block 121. A contract existed between J. C. Hunter, Jr., and the Six-Bar Ranch stating that at the conclusion of existing oil and gas leases, the Six Bar would exchange its sections for Sections 32, 42, and 44, Block 65, Township 2, Culberson County, which Hunter owned.

6. Biggs reported that one other half-section remained in private hands, the east half of Section 5, PSL Block 121. He said J. F. Walcott and Misses Pearl and Joe Cole owned the land. Because the tract was unfenced and Hunter had used a large portion of it for many years, Biggs expected a trade would be acceptable. [11]

In May 1964, Norman B. Herkenham, Regional Chief of National Park Systems Studies, visited some of the landowners Biggs had identified. In a memorandum written after his visit, Herkenham stated: "For the record, although it hardly requires emphasis, this visit was much overdue, and there has been considerable time for misapprehension and suspicion to breed in the minds of the people concerned." [12]

Herkenham found the land situation to be as Biggs had represented it. He was so impressed with the adamancy of the Hammacks' and the Glovers' refusals to sell their property that he recommended those sections be deleted from the park proposal. He felt the landowners' response stemmed partly from a general attitude that "if it helps Hunter in any way, we are against it," but he also felt that contacts made by Biggs and Kincaid with the Hammacks and Glovers had exacerbated the situation. In his trip report Herkenham wrote, "The principal hostility of the local people seems to be directed chiefly toward Mr. Glenn Biggs. . . . Mr. Biggs has made himself extremely unpopular through his aggressive dealings and attempts to option the property of the smaller landowners, both in the past and now, in connection with the park proposal." Herkenham doubted whether Hunter was aware of all of the actions of his representatives. [13]

Herkenham did not meet with F. G. Barrett, but the Glovers told him that Barrett's attitude would be similar to theirs. Herkenham realized that the Glovers probably had more interest in Barrett's land than Barrett did, since they leased the property. Because the scenic value of Barrett's half-section was important, Herkenham was reluctant to suggest that it be excluded from the park. [14]

Joseph F. Irwin of the Southwest National Bank Trust in El Paso represented the individuals who owned Section 21, PSL Block 121. He told Herkenham that the investors were already aware of the effect of the proposed park on their property. Irwin indicated that he knew of no overt resistance to including the section of land in the park, but the owners clearly expected any transfer of property to be financially advantageous to them. He thought an exchange might be possible. [15]

Herkenham did not contact representatives of either the Walcott/Cole or the Six-Bar Ranch interests during his visit. He reported, however, that he expected no problem with the acquisition of either tract. The agreement between Hunter and the Six- Bar Ranch would accomplish what the Park Service needed, and Herkenham believed an exchange with the Walcott/Cole interest would be "no serious problem." [16]

In 1970, when officials of the Park Service began full negotiations with the small landowners, the exchanges that had been anticipated were, in most cases, refused. The Federal Government was forced to purchase the Cole tract ($6,404), the Southwest National Bank Trust tract ($12,000), and the Barrett tract ($10,206). The exchange with the Six-Bar Ranch took place as planned, but the federal government paid an additional $5,400 to the Six-Bar to equalize land values. A quarter-section tract (Section 45, Block 65, Township 1, Culberson County) belonging to the Texas Pacific Land Trust, which neither Biggs nor Herkenham had mentioned, was exchanged for three-eighths of Section 30, Township 2, Block 65, Culberson County, but the Texas Pacific Land Trust retained a 60-foot right-of-way easement across their original section. [17]

The Hammack Exclusion and Easement

Early in 1964, Ona and Ed Hammack learned from Biggs and Kincaid that two sections of their ranch had been included in the proposed park. Biggs and Kincaid agreed that the land had no scenic value and was essential to the Hammack's ranching operation because it contained their primary water source. Acting on the advice of Biggs, the Hammacks wrote to Senator Yarborough to ask that their land be excluded from the park. They said that depriving them of the use of Section 17 would destroy their ranching operation. [18]

After hearing from the Hammacks, Yarborough expressed to the Park Service his concern for his constituents. Herkenham met with the Hammacks during his trip to Texas in May 1964 and discussed possible alternatives with them, including acquisition by the Federal Government that left water rights and life tenancy with them, or exchange for sections outside the park. Since neither possibility appealed to the Hammacks, Herkenham and Daniel Beard, Regional Director of the Southwest Region, concurred in recommending to Park Service Director George Hartzog, Jr., that Sections 7 and 17 be excluded from the park proposal. [19]

In June 1964, the Acting Assistant Director of the Park Service, C. Gordon Fredine, wrote to Senator Yarborough, reiterating the field assessments that found the Hammack property not essential to the development of the park and assuring Yarborough that the Hammack's property would not be acquired without their permission. Fredine hoped that this promise would remove the Hammack's objections to the park. [20]

Nearly two years later, in spite of recommendations and promises, the question of how the Hammack land would be handled was still not settled. In February 1966 Senator Yarborough discussed the situation with Park Service Director Hartzog. In a letter to confirm the points made during their conversation, Hartzog listed the sequence of acquisition procedures which would be utilized for the park lands, including the Hammacks': (1) purchase based on fair market values; (2) less than fee interest, such as a scenic easement, if such an interest met the needs of the park; (3) purchase with reserved use and occupancy by the owner for a specified period; and (4) acquisition by right of eminent domain. Hartzog emphasized that condemnation would only be used as a last resort. [21]

Both the House and the Senate subcommittees amended the park legislation to allow for omission of the Hammack sections from the park. Instead of the federal government having a fee interest in the Hammack's land, the legislation allowed a scenic easement, committing the Hammacks and successive owners to obtaining Park Service approval for any construction on Sections 7 and 17. [22]

Late in November 1967, after the major mineral rights donations were complete, the Park Service began final negotiations with the Hammacks to acquire the scenic easement that park legislation allowed. On June 14, 1968, for the sum of one dollar, the Hammacks conveyed a perpetual scenic easement, following the language of the legislation, to the federal government. The final clause of the easement granted the Secretary of the Interior or his representative the authority to allow deviations from the covenant as long as the deviations did not interfere with the purposes of the easement. [23]

The Hammacks accepted the easement for a number of years, but in 1976 they asked for a concession to allow construction on one of the sections. The Park Service approved their plans. In 1978, aware of the fact that Ed Hammack had a terminal illness and that both of the Hammacks were concerned that the easement clouded the title to their property, Donald Dayton, the Superintendent of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains, asked the Regional Director to consider removing the easement restrictions entirely. Dayton recommended the removal for two reasons: 1) the easement had been unnecessary in the first place, and 2) it would be a good public relations move. [24] However, when the Solicitor General determined that legislation would be necessary to remove the restrictions, the subject was dropped. [25] Ona Hammack died on May 31, 1984, and Ed Hammack died March 26, 1985. Since the deaths of the Hammacks, the heirs have expressed no concern about the easement restrictions. [26]

Acquisition of the Glover Property

In July 1964, when Glenn Biggs reported the ownership of the small tracts of land within the proposed park to Robert Barrel, he mentioned water sources on the Glover property that made it particularly valuable to the owners. He also revealed that the Glovers had previously deeded a small portion of their property, a one-half-acre tract containing remnants of the old Butterfield stage station, to American Airlines. The airline company had planned to restore the stage station but when costs made the plans unfeasible, the property reverted to the Glovers. Biggs speculated that the Glovers might be convinced to make a similar agreement with the Park Service. [27]

The same day that he wrote to Barrel, Biggs also wrote to Noel Kincaid to thank him for helping provide the information for Barrel. Biggs told Kincaid that Barrel had indicated to him in a phone conversation that the Park Service did not find the Glover tract particularly significant. If the Glovers were willing to sell a small piece containing the Butterfield stage station, the Park Service would be interested in acquiring that portion of their property. Biggs ended his letter by saying, "I will be eternally grateful for all the help and kindness extended to me by you and I will assure you that I will do everything possible to see that you are not embarrassed over the acquisition of any of the aforementioned property." [28]

Noel Kincaid was a forthright man and a long-time friend and neighbor of the Glovers. In March 1964 he took matters into his own hands and told the elderly couple of the proposed park and how it affected their property. Then he notified officials at the Southwest Regional Office of what he had done and of the reaction of the Glovers. He said the Glovers had no previous knowledge of the proposed park and were extremely upset by the news that their property was included within the boundaries. Asking for more information to share with the Glovers, Kincaid learned that Barrel's earlier opinion about the Glover property no longer held true. Inclusion of the Glover property in the park proposal had become important for two reasons: to provide access to Pine Spring Canyon from Highway 62/180 and allow preservation of the Butterfield stage station ruins. Regional officials apparently had no reservations about allowing Kincaid to intercede with the Glovers on the part of the Park Service. They asked him to reassure the elderly couple that they would be treated fairly when the time came to acquire their land. [29]

Records are not clear about whether Glenn Biggs knew of Kincaid's visit to the Glovers. However, when Biggs stopped to see the couple a short time later, he was not well received. Finding that Biggs had brought them an option to sign, the Glovers literally ran him off their property. In a letter to the Glovers dated March 16, 1964, Biggs told them he would leave for Washington, D. C., the following day to talk with congressmen about deleting their property from the park proposal. He said, "This was what I wanted to discuss with you while visiting with you last week, but I never had a chance to finish. You won't believe this, but I had nothing to do with the Park Service including your [land] in the designated area. As a matter of fact, and it is on record, I tried to get them to not include any other property except that of J. C. Hunter, Jr." [30]

After his trip to Washington, Biggs again wrote to the Glovers. He had talked with Senator Yarborough and Representative Pool and reported both were sympathetic. Biggs tried to explain the position of the Federal Government regarding the Glover's property, saying a 50- to 99-year option to purchase their land would probably be sought. He also acknowledged the fact that the Glovers probably would not be interested in selling for as long as thirty years. Biggs advised the Glovers that the government would approach them "merely on the basis of finding out your interest--not on the basis of forcing you off your property." [31]

Soon after Kincaid and Biggs talked with the Glovers, a delegation of interested persons from West Texas and southeastern New Mexico met in Carlsbad to discuss testimony to be delivered at the upcoming Senate subcommittee hearings on the Guadalupe Mountains park bill. As a result of the March 24th meeting, Carlsbad Mayor Hampton Martin and New Mexico Governor Jack M. Campbell decided to speak against the acquisition of the Glover property during the hearings. They believed the cafe operated by the Glovers had become an institution in West Texas and that the Glovers should be permitted to retain their property. [32]

After his visit with the Glovers in May 1964, the report Norman Herkenham filed was not optimistic. He found them "openly hostile to the park proposal and to any suggestion of including any part of their property within it. . . . [T]here was absolutely no opportunity for compromise" as far as the Glovers were concerned. Herkenham determined that the only critical acquisition would be the small tract of the Glover's land containing the ruins of the Pinery Stage Station. He suggested that although the Glovers' attitude might soften, the only way to eliminate their opposition to the park was to delete their property from the proposed park boundaries. [33] Regional Director Daniel B. Beard passed Herkenham's recommendations on to Director Hartzog and suggested that the park bill be revised to say that the Glover property would be acquired only with concurrence of the owners. [34]

The recommendations of Park Service personnel regarding the Glover property brought about no bill revisions. The Glover tract remained a part of the park. In 1966, shortly after passage of the park legislation, Howard Cameron, Realty Specialist for the Park Service, wrote a memorandum to the files, describing the Glovers as very much opposed to the park, according to people in the area. He had spoken with Duane Juvrud, the Hammacks' attorney and a friend of the Glovers. Juvrud advised extreme caution when dealing with the Glovers. Having had no personal contact with the Glovers and even unaware of whether Glover was married, Cameron recommended trying to purchase the property with a life estate for Glover. [35]

Two years later, in December 1969, J. E. Williamson, a negotiator from the Office of Land Acquisition and Water Resources of the Western Service Center, visited the Glovers. He hoped to obtain their permission for an appraisal of their property. In his notes, he bluntly assessed the Glover property and situation:

This is a problem tract. Owners are old and very hostile to the park. Mr. Glover is 91, Mrs. is 77. They have lived on or near the tract for 55 years. . . . The improvements consist of several old unused tourist cabins and an old building along the hwy. which is used as living quarters, service station and a very dirty little lunch stand. From what I could see the improvements are of little value.

. . . [T]he purpose of my visit was to obtain permission for an appraisal. . . . I made several attempts to communicate with Mrs. Glover and go over the map with her. I failed. She would take-off on a verbal barrage against the park, about how I was trying to steal their land and that our appraisal would be just another trick by another crook. . . . She would talk only on their refusal to have anything to do with the park. She would not listen. [36]

Williamson also met with Bertha Glover's brother, T. C. Miller, a retired Park Service ranger who lived in Carlsbad. Miller was not surprised at the Glovers' response and told Williamson he doubted that there was an answer to the problem. He recommended waiting until both Glovers died, since he did not think the Park Service would condemn the property. Williamson advised Miller not to believe that condemnation would not be utilized. Miller agreed to try to reason with the Glovers. [37]

A month later Williamson met with the Glovers again. This time Mrs. Glover said they would not sell their property for less than a million dollars, but asked Williamson what the federal government would offer. He responded that until an appraisal had been made, he could not make an offer. Mrs. Glover again refused to allow an appraiser to look at the property. Williamson added a parenthetical note to his report, saying he thought an earlier estimated appraisal of $50,000 to $75,000 was too high. [38]

As a means of acquiring the Glover property, the new Regional Director of the Southwest Region, Frank Kowski, opposed condemnation. He suggested to Edward Hummel, Assistant Director of Park Management for the Park Service, an arrangement with the Glovers that would permit stabilization and preservation of the stage stop ruins. Hummel responded negatively to this idea, saying that federal funds could not be expended for historic preservation if the property were not under the jurisdiction of the federal government. Alternatively, Hummel suggested offering the Glovers a life estate in the property. However, if that offer was refused, he recommended filing a complaint reserving a life estate, believing such action would reduce "the sting of condemnation." [39] Carl O. Walker, Acting Director of the Park Service, instructed the land office of the Western Service Center to try negotiating with the Glovers one more time. If that effort failed, he recommended filing a complaint action. [40]

In April 1970, J.E. Williamson met with the Glovers again. To his relief, the Glovers had arranged for an attorney, Hudson Smart, of Abilene, Texas, to represent their interests. At Smart's suggestion, he and Williamson talked alone. Williamson offered $35,000 plus a life estate for the Glovers which allowed them the non-transferrable right to continue their business as long as they wished or lived. Because Smart was not familiar with local land values he preferred to wait to respond to the offer until the property had been appraised, telling Williamson he had made arrangements for an appraisal before he left Abilene. [41]

It is unclear whether Smart refused the offer of the government to the Glovers or if he simply failed to produce an appraisal. In any event, in June 1970 the government initiated condemnation proceedings against the Glovers. The Glovers submitted two appraisals in September 1970, one for $69,300 and the other for $115,000. In March and June 1971, two government appraisers evaluated the property at $35,000 and $30,024. [42]

The condemnation judgment, filed March 10, 1972, gave the Glovers $55,000 for their land. The presence of water wells on the land justified the increase over the government appraisals. The judgment also gave the Glovers the right to use and occupy the property as it was then improved until the death of the last surviving spouse. [43] The Glover property was the last piece of land to be acquired before official establishment of the park.

The Shivers Mining Claims

In November 1964, Bill Orr, a member of the regional staff for National Parks Systems Studies, asked Biggs and Hunter for information about mining claims in Sections 6 and 12, Block 66, Township 1, Culberson County, parts of the proposed park. Hunter informed Orr that former Texas Governor Allan Shivers owned in fee (surface and minerals) "The Valley Mining Claim," a 20.66-acre tract in Section 6. Hunter himself owned the surface rights to the remaining 725.82 acres in Section 6 and the State of Texas owned the mineral rights. In Section 12, Shivers owned 20.66 acres in fee, the "Hard Scrabble #1." He also owned all valuable mineral rights but oil, natural gas, coal, and lignite under three other 20.66-acre tracts in Section 12, the "Shary #1," the "Leon Brown," and the "Mary O'Brien" mining claims. Hunter owned all surface rights to Section 12, and the State of Texas owned all mineral rights to the entire section except for Shivers's claims. [44]

In his letter to Orr, Hunter summarized the unsuccessful core drilling done by the Eagle-Picher Company on one of the Shivers claims in 1962. He suggested that the willingness of the Eagle-Picher owners to relinquish their lease reflected the nominal value of Shivers's claims. [45]

When Kornelis and Cameron made their visit to Texas in October 1967, they approached Shivers's business manager, Blaine Holcomb, about the donation of the mineral rights. Holcomb was not receptive to their request and suggested that the tracts be excluded from the park. [46] Four months later, Glenn Biggs, a personal friend of Shivers, contacted Holcomb independently about the mineral donation. Holcomb said that Shivers would donate his claims if their appraised values totaled between $40,000 and $50,000. He wanted Biggs to find an engineering firm to conduct the appraisal. Biggs contacted Cameron to pass on the information and to inquire about who might make the appraisal. Cameron was unable, however, to suggest an engineering firm. [47]

Cameron waited six weeks. In April 1968 he called Holcomb again. Holcomb advised him that Biggs was handling the appraisal of the claims and suggested Cameron contact Biggs to learn the results of the appraisal. He said he thought John Kelly of Roswell (the same man who earlier had done the mineral report for Secretary Udall) was the mining consultant doing the work. Holcomb also informed Cameron that if the completed appraisal amounted to about $50,000 he would ask the Internal Revenue Service for a ruling about the Shivers donation. [48]

In November 1969, when the Hunter land acquisition was nearly complete, J.E. Williamson, the negotiator who was also working with the Glovers, contacted Biggs to determine the situation with Shivers. Biggs said he had exhausted his contacts and had been unable to find an appraiser. Recommending that he and Williamson visit Shivers in person, Biggs arranged a meeting in early December. [49]

Although other matters prevented Biggs from keeping the appointment, Williamson met with Shivers. At first Shivers professed no knowledge of the mining claims, but he later recalled the mining operation and began reminiscing. He claimed the mine had produced in the past and would again, given the right economic climate. When Williamson explained the provisions of the act that authorized the park, and asked whether Shivers would donate his mineral claims, Shivers responded negatively. Shivers ended the conversation by suggesting that Williamson arrange a meeting with Holcomb in a week or two. He promised to discuss the donation with his business manager before that time. [50]

A few weeks later, on December 18, 1969, A. W. Gray, Assistant Chief of Land Acquisition and Water Resources for the Western Service Center, visited Shivers in an effort to secure the mining claims. This time Shivers said he wanted a $25,000 valuation for the claims. He expected the Park Service to produce an appraisal for that amount and he also wanted the Park Service to get the Internal Revenue Service to agree to the deduction. In his trip report, Gray speculated about the tax benefits to Shivers of a sale rather than a donation, noting that a capital gain would be taxed at half the amount of a donation. Therefore, purchase of Shivers's claims would allow a lower appraisal. [51]

In July 1970, negotiator Williamson met with Holcomb again. He reviewed the previous meetings and explained that the establishment of the park was being blocked by the outstanding interests of Shivers. Holcomb "bristled" at the suggestion and maintained that it was the federal government that was holding up the park by not providing the $25,000 appraisal. Williamson explained once again that government appraisers could not arrive at that figure. [52]

After more discussion, Williamson succeeded in interesting Holcomb in the idea of a cash purchase of the two fee tracts, made with the understanding that the three mining claims would be donated. He said the federal government was prepared to offer $1,000 for each of the two fee tracts, 100 percent more that the appraised values. Holcomb refused to consider $1,000 per tract and suggested $5,000 as a more reasonable figure. Williamson expressed his view that $5,000 was out of line and far beyond the Department's authorization. Holcomb then telephoned Shivers in New York City and asked Williamson to leave the room while they talked. The result of the conversation was that Shivers was unwilling to accept $2,000, but was agreeable to $10,000. Williamson left an offer to sell form for Holcomb and Shivers to fill out with the sale price of their choice. Holcomb assured Williamson that it made no difference to Shivers whether the offer was accepted or not. [53]

When John Ritchie, Chief of Land Acquisition for the Western Service Center, received Williamson's report, he solicited the help and advice of Director Hartzog, stating that the $10,000 offer could not be supported by appraisals, but it was considerably lower than the earlier $25,000 offer. Ritchie felt his only alternative was to make a lower counter-offer. [54]

Frank Kowski, Regional Director of the Southwest Region, also intervened. He contacted Edward A. Hummel in the Washington office and suggested that Congressman White or Senator Yarborough might be able to talk with Shivers and overcome the impasse. He ended his letter by suggesting that some other means than raising the appraisal needed to be found to give Shivers his desired tax deduction. [55]

A week later, John Ritchie wrote a memorandum to the file, stating: "I am accepting the option on the properties owned by ex-Governor Allan Shivers within Guadalupe National Park, Texas. While I do not believe the acceptance can be justified on the basis of value there are other factors involved which justify such action." He said that he acted under the direction of Philip O. Stewart, Chief of the Land Acquisition Division of the Park Service. [56] On November 2, 1970, Allan Shivers signed one deed donating his three mineral interests within Guadalupe Mountains National Park and another deed conveying his two fee interests to the federal government for $10,000. [57]

The McKittrick Canyon Right-of-Way Exchange

Even before the official establishment of Guadalupe Mountains National Park on September 30, 1972, park personnel realized the existing access road to McKittrick Canyon presented a serious problem. When Wallace Pratt donated his land in McKittrick Canyon, he gave the government a choice of access routes. The route was chosen from a map, rather than from a survey of the terrain. The chosen right-of-way proved to be located in a canyon drainage where road construction would be extremely expensive. Instead of using this right-of-way, visitors to McKittrick Canyon used an existing ranch road, belonging to Wallace Pratt's daughter-in-law, Alice Pratt. In April 1973, the Carlsbad Chamber of Commerce indicated their displeasure to the Park Service when they learned that Alice Pratt had put a daily limit on the number of cars using her road: four on weekdays, ten on weekend days. Although Park Service officials already had begun negotiating for a land exchange with Alice Pratt, Congressional legislation authorizing the exchange would require considerable time. [58]

Three years passed before negotiations with Alice Pratt, Creighton L. Edwards, and Nancy Jane Tucker, the joint owners of the approximately 80 acres in question, were complete and legislation authorizing the exchange was passed. Donald Dayton, Superintendent of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks during this period, recalled that negotiations with Alice Pratt required extreme delicacy. The land exchange brought back hard feelings that had existed among the Pratt children at the time of their father's land donation. They felt they had already given enough. Wallace Pratt refused to intercede in the proceedings because he had deeded the property containing the desirable right-of-way to his daughter-in-law and no longer had control over the matter. [59]

In spite of her concerns about family feelings, Alice Pratt's primary concern was that Al Parker, the man who leased the ranch, was satisfied with the road and the exchange agreement. Before Pratt agreed to the Park Service proposal, surveyors for the government marked the route of the road so that she could see it on the land. [60] One of the first concessions required was construction of cattle underpasses to allow Parker's cattle access to grazing and water. [61] When the subject of transfer of mineral rights came up, Pratt was adamant that Nancy Jane Tucker not be required to relinquish her 2/9 mineral interest in the property. In a telephone conversation with Brewster Lindner, Chief of Land Acquisition in the Southwest Regional Office, Pratt said that "the mere mention of Nancy Jane Tucker's name" made her want "to drop the whole proposal." She feared that even though Lindner had assured her that Tucker's interest would not be required, someone later would demand that the interest be extinguished and then another "horrible" family feud would erupt. Within two weeks the regional office provided an Administration Certificate guaranteeing Tucker would not be approached for at least five years from the date of the property exchange. [62]

As negotiations continued, park personnel tried different ways to limit the number of cars crossing the Parker ranch. Initially, visitors obtained keys to the gate of the ranch road from the Frijole contact station and returned them on an honor system. Although this method limited access to McKittrick Canyon, it still did not guarantee that visitors would stay on the road and would not disturb Parker's land or cattle. In June 1973, in an effort to allow more persons to visit the canyon each day, a shuttle-van service was instituted. A ranger drove the 15-passenger van that departed hourly from the McKittrick Canyon turn-off on Highway 62/180 and returned on the half-hour. While this method created more traffic on the ranch road, it provided better visitor control on the private property. [63]

Alice Pratt recognized the care with which the Park Service personnel handled the exchange of the McKittrick Canyon right-of-way. Her letter of March 1976, transmitting the signed deed to Lindner said, "I hope that the end of these dealings will not be the end of our contact as it has been a pleasure to deal with representatives of the government with such kindness and consideration as yours." However, Al Parker had to contend with the Park Service and the public for two more years. The first phase of construction on the road to McKittrick Canyon was not finished until the summer of 1978. In May 1980, negotiators completed the exchange of mineral rights for the right-of-way. [64]

West Side Access Road Right-of-Way

Part of one section of the land acquired from Hunter outside of the park boundaries had been designated as an access route from Highway 62/180 to the west side of the park. Rather than retain the entire section when only a road right-of-way was needed, the government traded all but a 200-foot-wide strip through the section, plus half of another of the sections outside the park boundary, to the State of Texas for the same amount of land in Brewster County, Texas, to be used by Big Bend National Park. The exchange was completed on November 4, 1974. [65]

A scenic easement, 1,320 feet wide (660 feet on either side of the right-of-way), accompanying the right-of-way gave the Park Service the authority to approve or disapprove the construction of buildings within the area of the easement, to prohibit the removal of timber or shrubs within the area of the easement without written approval, to prohibit the placement of any offensive or unsightly material upon the easement land, and to prohibit signs or billboards except those no larger than 18 by 24 inches, advertising the sale of property or produce. [66]

Acquisition of the Texas Highway Department Maintenance Area

At the time Guadalupe Mountains National Park was authorized, the Texas highway department had a one-acre maintenance facility on the north side of Highway 62/180, across from the Glover cafe at Pine Springs, in an area of scenic value to the park. The highway department was unwilling to abandon the camp, claiming it was necessary for winter road maintenance. To facilitate removal of the maintenance facility, the Park Service agreed to provide the highway department with access right-of-way and water to a new site for their facility near the mountain pass. In 1982 the Park Service and the Texas Highway Department signed a cooperative agreement to allow the exchange of the maintenance camp property for a road easement through park property to a new highway department facility, to be constructed on the south side of the highway, just outside the park boundary. Under the terms of the agreement, the old maintenance camp site would be cleared of all buildings and structures within a "reasonable length of time" after the new facility was built. Deeds would be exchanged when the old site became surplus to the needs of the State. [67] The agreement also provided that the Park Service would provide water, on a cost basis, to the new maintenance camp.

The highway department occupied its new camp in March 1984 and completed clearing the old site in April 1986. As of January 1988, however, the State of Texas had not conveyed the old 0.99-acre camp site to the government. A complication in completing the exchange was the reserved right-of-way belonging to the Texas and Pacific Land Trust that overlapped the location of the road to the new highway camp. Although primarily a technical flaw and not a real problem, the existence of this prior right-of-way was overlooked when the cooperative agreement was prepared and signed. [68]

Excess Land Acquired Outside the Park Boundaries

In 1988, two and one-half sections remained of the land outside the park boundaries that was acquired for exchange purposes. Section 18, Township 2 South, Block 65, Culberson County, was used as a temporary residential area for park employees until 1982, when permanent housing was completed. Although the Park Service considered disposing of this section in 1978, Superintendent Dayton recommended it be retained for its valuable water source and to help preserve scenic views in Guadalupe Pass. [69]

When the federal government acquired Hunter's land, El Paso Natural Gas Company had a 99-year lease, terminating in 2046, on approximately 80 acres of Section 25, Block 120, PSL, Culberson County. The leased site contained company-owned residences. The remaining acreage in this half-section, however, was unencumbered.

In 1988, the third excess section, Section 13, Block 120, PSL, Culberson County had not been developed and was situated immediately south of the southern boundary of the park and north of Highway 62/180.

In most cases, acquisition of the mineral and surface rights to the park lands took place with little public controversy. After the concessions made during the Congressional hearings regarding reversionary mineral rights, the State of Texas and Texaco donated their mineral rights with little hesitation. While the government was not able to exchange as much land as had been anticipated, the small landowners, with the exception of the Hammacks and the Glovers, did not object to selling or exchanging their property. In the case of the Hammack tract, the park legislation provided for a scenic easement, which made fee acquisition unnecessary. The Glover property, however, had to be acquired through condemnation. Negotiations with the Glovers marked the beginning of a sensitive park issue that was still a management concern in 1988.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

gumo/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 05-May-2001