|

Guadalupe Mountains

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter CI:

PLANNING FOR THE PARK--THE 1970S

Planning in the National Park System

Decisions affecting the national parks are not made quickly. To ensure that each park is preserved, used, and developed in accordance with its specific purposes, planning takes place systematically, following agency guidelines. The most general planning document is the park's Statement for Management. The Statement for Management, prepared by the superintendent and staff of the park, describes the park's purpose, its current management and use. It identifies influences that affect the park, reports the status of research projects, and identifies major issues and management objectives. The Statement for Management does not suggest ways to handle issues or to meet objectives. Ideally, this document is updated every two years.

According to the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978, each park should have and regularly revise a General Management Plan, the next higher level of planning above the Statement for Management. The General Management Plan replaced the Master Plan, the planning document that was in use when Guadalupe Mountains National Park was authorized. Both the Master Plan and the General Management Plan set forth the plan for management of the park and for its use by the public. The primary difference is that in the draft stage the General Management Plan provides several alternatives and sets out the environmental impact of each alternative. Alternatives are compared and evaluated before adoption of one for the General Management Plan. The Master Plan required preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement, setting forth the environmental impacts of the plan to resources of the park and describing mitigating measures and unavoidable adverse effects. The Master Plan and the accompanying Environmental Impact Statement were subject to review by the public and other government agencies before acceptance.

Development Concept Plans are the most specific level of planning and are created to implement the strategies suggested in the General Management Plan or Master Plan. They also require Environmental Impact Assessments. Drafts of Development Concept Plans are circulated for review by the public and by other government agencies. Other planning documents at the same level as Development Concept Plans that have affected Guadalupe Mountains National Park include a Wilderness Recommendation, an Interpretive Prospectus, and Resource Management Plans, as well as studies undertaken to find solutions to specific questions.

The process of planning for Guadalupe Mountains National Park began in 1961, after the Pratt family donated their land in McKittrick Canyon. At first, park managers treated McKittrick Canyon as a detached unit of Carlsbad Caverns, but after Congressional authorization of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, the parks were managed as separate entities that shared common regional interests. Although all major planning documents were in place by 1978, the planning process was ongoing. During the 1980s park managers drafted new versions of a number of planning documents.

A discussion of planning for Guadalupe Mountains National Park cannot be organized neatly either by chronology or by topic because much of the early work was interrelated and accomplished concurrently. Therefore, the first section of this chapter discusses development of the Master Plan and documents related to it: the Wilderness Proposal, the Development Concept Plan for Pine Springs, and the tramway study. Subsequent sections are arranged in topical order.

Master Planning Process

In 1961, Oscar Carlson, Superintendent of Carlsbad Caverns, assumed the responsibility for administering McKittrick Canyon and drafted a development plan for the area. He proposed using the Ship on the Desert as a visitor center and headquarters, and establishing a campground at the mouth of the canyon. He envisioned a circular trail system in the canyon as well as two short nature trails near the visitor center. Carlson estimated that seven full-time personnel would be required to staff the McKittrick branch of Carlsbad Caverns and suggested that ten residences would be needed. He emphasized the importance of obtaining J.C. Hunter's property in McKittrick Canyon to eliminate automobile traffic in the canyon. [1]

Three members of the planning staff at the Southwest Regional Office reviewed Carlson's plan. While two of them found his plan too ambitious, the third thought the road in the canyon should be improved as far as the Pratt's stone cabin, saying visitors would object to walking over a road that was obviously used by vehicles going to Hunter's property. Ultimately, all three reviewers recommended moving slowly and waiting to see whether more land would be acquired. [2]

Carlson's plan never went beyond the proposal stage. By 1965 negotiations to acquire Hunter's ranch were well advanced and legislation to establish Guadalupe Mountains National Park was being considered. A Master Plan brief, compiled in October 1965, outlined the basic form that all subsequent planning for the park would follow: Guadalupe Mountains National Park would be managed as a natural park with emphasis on its unique geological and biological features. Historical and archeological features would be of secondary importance. [3]

The Master Plan brief also identified the park's major problem: how to provide visitor access to the small and ecologically fragile areas of McKittrick Canyon and the Bowl. A mechanical lift was proposed as the means of transport to the Bowl, while tours in an open-sided vehicle, guided by a concessioner, were suggested as a way to handle visitation in McKittrick Canyon. Hiking and horseback trails would provide access to other parts of the park. The ranch complex at Frijole Spring would contain the visitor center, a lodge, and a major campground. A facility providing meals, sleeping quarters, hiker supplies, and a horse corral would be located on Pine Ridge, at the top of the mechanical lift. Before further planning took place, surveys of plant and animal life within the park were needed, as well as an assessment of the possibility of getting water to facilities on the ridge. The writers of the brief expected that Guadalupe Mountains National Park would be a self-sufficient organization and would not utilize the existing facilities and staff of Carlsbad Caverns. [4]

President Lyndon Johnson signed the bill authorizing Guadalupe Mountains National Park in 1966, but the lengthy land acquisition process lay ahead. In the meantime, planning continued. In June 1969 work began on a Master Plan study for Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains. Members of the House committee investigating the establishment of a park in the Guadalupes had been concerned that McKittrick Canyon extended into land managed by the U.S. Forest Service. They had recommended that the Park Service and the Forest Service work together to manage the area. For that reason, managers from both agencies tried to work out a Regional Master Plan. [5]

By late 1969, the working version of the joint Master Plan included a road through the Lincoln National Forest from Carlsbad Caverns to Dog Canyon, where a road through Guadalupe Mountains National Park would connect with Pine Springs. Soon after this draft had been prepared, and, for reasons that the records do not make clear, the master planning team abandoned the idea of a regional or joint Master Plan for Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains.

Early the following spring the team completed drafts of separate Master Plans for the parks. The primary concern of the planners for the Guadalupe Mountains National Park area was to achieve the proper balance between preservation and use. In the draft completed in 1970, a tramway, rather than the previously proposed road, provided access to the high country. The planning team decided that McKittrick Canyon would be devoted primarily to scientific research with visitor use limited to that which would not have a significantly adverse effect on the ecology of the canyon. [6]

Outside forces, including changing cultural values, affected planning for Guadalupe Mountains National Park. During the late 1950s and early 1960s visitation to state and national parks increased rapidly. While MISSION 66, the decade-long (1956-66) effort by the Park Service to upgrade and develop existing facilities, seemed to provide what visitors to the parks needed, it was not in step with beliefs of the new breed of conservationists. Conservationists traditionally had been among the chief supporters of the Park Service. However, the environmentalists, who were the conservationists of the 1960s and 1970s, assumed a new role in park planning. Instead of providing consultative and usually supportive guidance, they became a force in active opposition to any park development that took place at the expense of nature. [7]

Within the Park Service, planning for Guadalupe Mountains began in the wake of the spirit of development that typified MISSION 66. George Hartzog, Jr., Director of the Park Service, and the officials who worked under him believed roads could have a negative impact on park lands. Therefore, they wanted planners to develop alternative methods of in-park transportation. Hartzog and his staff directed that the Master Plan for Guadalupe Mountains would include a tramway to make the beauties of the high country accessible to the largest number of visitors with the least impact on the park's resources. However, the Wilderness Act of 1964, and the environmentalists who supported the values embodied in the act, created major stumbling blocks for the tramway concept.

According to the Wilderness Act, any roadless areas of more than 5,000 acres within a national park must be considered for wilderness designation. Guadalupe Mountains National Park contained two such areas, one of which comprised 62,300 acres, a major portion of the park. A Congressionally designated wilderness is an undeveloped area of federal land of primeval character, without significant human developments or habitation and is protected and managed to maintain that character. Wilderness designation precluded developed campgrounds and paved trails. In the case of Guadalupe Mountains, it also meant that water resources could not be developed in the high country, thereby limiting how long campers and hikers might stay. Similarly, wilderness areas may not contain roads nor permit motorized vehicle use, except in rare emergencies. Rescues and fire-fighting must be accomplished on foot or horseback or by helicopter, limiting aid to stranded or injured visitors. Environmentalists sought this type of designation for much of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, believing that wilderness should be preserved intact for future generations. Wilderness designation for Guadalupe Mountains National Park meant that only visitors willing to enter the wilderness on its own terms would have the privilege of seeing much of the land that embodied the values of the park.

The battles for wilderness designation for the park and for the Master Plan were fought in the public arena, as law required. The tramway to the top of the escarpment that the Park Service proposed to build became the issue on which planning hinged, since its presence or absence ultimately determined the character of the park. Opinions expressed at the hearings in 1971 have been discussed earlier in this paper. [8] As a result of those hearings and as a compromise between development and wilderness protection, park planners adopted an alternative tramway plan proposed by a group called Americans Backing Better Park Development. The original plan set forth by the Park Service had proposed a tramway from near Frijole to a point on the east escarpment between Pine Top Mountain (later renamed Hunter Mountain) and McKittrick Canyon. This plan provided easy access from the upper terminus to the Bowl, the summit of Pine Top, and an overlook above McKittrick Canyon. The alternative plan shifted the proposed tramway to Pine Springs Canyon with a terminal below Guadalupe Peak, thus removing heavy visitor traffic from a fragile area while still providing a spectacular view.

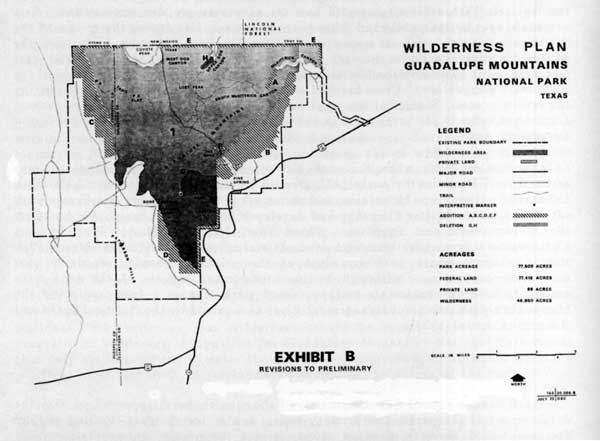

Environmental concern expressed during the public hearings also changed the planners' Wilderness Proposal. Relocating the tramway freed an additional 3,000 acres to be added to the wilderness proposal. Another 5,000 acres, primarily on the west side of the park, and including areas that had previously been excluded as "management" areas for fire control and rescue provisions also were added. As a result of input by the public and other government agencies during the review of the Wilderness Proposal and its accompanying Environmental Impact Statement, the proposed wilderness area in the park was increased from 39,000 acres to 46,850 acres (see Figure 15). The Environmental Impact Figure 15. The areas recommended for wilderness designation. Cross-hatched areas were added after public input during the review process. Statement was approved in August 1973. Wilderness designation for the proposed 46,850 acres came in 1978 under Title IV of the National Parks and Recreation Act. [9]

In September 1972, when the park was established, master planning still was incomplete. However, by early 1973, Donald Dayton, Superintendent of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains, and personnel at the Denver Service Center were satisfied with the Master Plan they had developed for the park, which was based on the revised Wilderness Proposal. Three years later the Master Plan and its Environmental Impact Statement received official approval. In 1988, the Master Plan that was approved in 1976 remained as the primary planning document for Guadalupe Mountains. Although by that time many aspects of the plan were outdated, funding constraints had prevented park managers from replacing the Master Plan with a General Management Plan, as required by the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978.

Master Planning Process (continued)

Master Plan

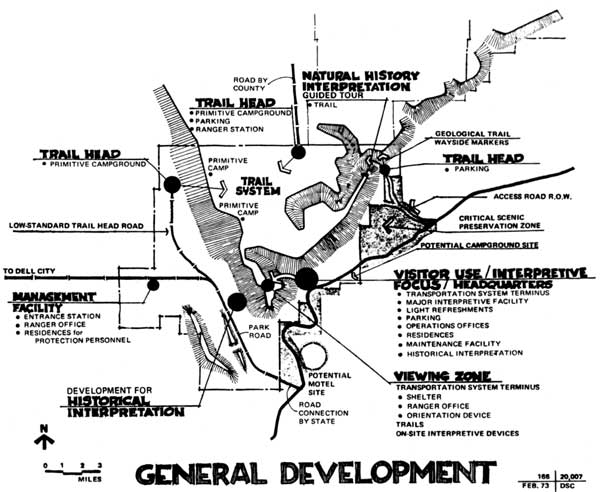

Figure 16 shows the major components of the plan that was approved in 1976 for development of the park. The primary visitor center for the park, located at Pine Springs, would provide parking, food service, restrooms, interpretation, and orientation. Pine Springs also would be the lower terminus for the tramway to Guadalupe Peak. The upper terminus, just below the summit, would have a shelter, orientation devices, and a staffed contact station. From Guadalupe Peak visitors would have spectacular views of the high country, the salt flats, and the desert. During the ride to the summit, visitors would learn of the geological significance of the fossil reef and the various biological life zones represented in the park. From Guadalupe Peak, visitors who wished to do so could enter the wilderness area. [10]

|

| Figure 15. The areas recommended for wilderness designation. Cross-hatched areas were added after public input during the review process. |

The west side of the park would be developed for low-density use. Cooperation with the Texas highway department would be necessary to provide an access road to this part of the park. Visitor access would be controlled, entrance fees collected, and information services provided from an entrance station on the west side. A park road, traversing part of the length of the west side of the park, would connect on the western boundary with a county road leading to Dell City. Near this junction, a primitive campground and parking area would be located. A spur road would lead from the park road to Williams Ranch. [11]

Access to the parking area at the mouth of McKittrick Canyon would be by road and private automobile. Guided foot trips into the canyon, lasting approximately three hours, would interpret geology and the riparian and aquatic communities. An interpretive center would provide information about the canyon for visitors who do not take the tour. [12]

The high country would be reserved for wilderness-type experiences. Hikers would have access to the high country from three main trailheads: the main trail, originating near Frijole and leading up Pine Springs Canyon; a secondary trail originating in the northwest corner of the park; and, another secondary trail beginning in Dog Canyon, with a primitive campground at the trailhead. The trail system would connect with a ridge trail following the McKittrick Canyon divide. Development of the Dog Canyon trail and campground would depend upon the county providing an access road to the area. [13]

The planners recognized the need for camping facilities for park visitors. While providing for a temporary campground at Pine Springs Canyon, the planners expected that private enterprise would develop permanent campgrounds near the park. The plan provided, however, that if such developments did not occur within five years after approval of the Master Plan, the Park Service would construct campgrounds within the park. [14]

The Master Plan proposed various forms of management for the resources of the park. Geologic features would be preserved by prohibiting destructive or obstructive development. Flora and fauna would be actively protected by neutralizing the influence of humans. Water for human use would be obtained only where its extraction would not be detrimental to the park. Visitation to McKittrick Canyon would be controlled and horse use prohibited in the lower canyon. Use of the Bowl would be concentrated on the edge of the relict forest, which would be interpreted for visitors as a "museum object" and for scientists as a "laboratory" for approved research. In the primitive areas, day use would predominate; overnight horse trips would be prohibited. The trail system would be designed to avoid fragile areas. Historic resources already identified, including Williams Ranch, Frijole Ranch, and the Pinery Stage Station would be preserved; other historic and archeological sites would be preserved until fully evaluated. The plan also classified the park lands into five categories to aid management decisions: developed areas, buffer areas, research (delicate) areas, primitive land, and historic and cultural sites. [15]

|

| Figure 16. The general plan for development of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, as set forth in the Master Plan approved in 1976. |

The Master Plan set forth the administrative facilities necessary for the operation of the park. It provided for residences and maintenance facilities at Pine Springs; a contact station, maintenance facility, and residence on the west side; and a ranger station at Dog Canyon. To provide access to McKittrick Canyon, an exchange of right-of-way would be required. [16]

Finally, the Master Plan outlined management objectives for visitor use and resource management. The planners desired that all visitors be able to see the park from the high country as well as from below and that the modes of access to these points be within the physical and financial capabilities of the majority of visitors. Interpretation would focus on geology, the unique ecosystems found in the park, and the historic resources. Development in fragile areas would not take place until research was completed showing there would be no adverse effects on the natural resources located there. The water needs of native plants and animals would be met before human uses were developed. Fire would be utilized as a management tool. [17]

Master Planning Process (continued)

Pine Springs Development Concept Plan and the Tramway Study

In 1973, planning began for the Pine Springs area. The area to be considered included Guadalupe Peak, El Capitan, the meadow below Guadalupe Peak, Pine Springs Canyon, the ranch house and associated buildings at Frijole Spring, the ruins of the Pinery, the temporary ranger and information station, a primitive campground, the trailhead for hiking and horse trails into the high country, several historic and prehistoric archeological sites, a number of springs, the Glover property, and the maintenance and residence areas for the Texas highway department.

Planning for Pine Springs took place simultaneously with the development of the Master Plan and a study of the proposed tramway. The tramway study, completed in 1974, recommended utilization of a mechanical system called Skytram (a registered trade name). Skytram was composed of individually powered cars that moved along a fixed cable. Each car had a capacity of 22 persons and would be driven by an operator. The lower terminus of the tram would be a part of the main visitor center at Pine Springs, where visitors would be introduced to the park's resources. The proposed route of Skytram closely followed the walls of Pine Springs Canyon, running north from the visitor center at Pine Springs, then west to a landing in a meadow at an elevation of 8,150 feet. From the meadow, a separate shuttle would carry passengers to the ledge about 500 feet below Guadalupe Peak, at an elevation of 8,675 feet. From there, the peak would be accessible by a foot trail (see Figure 17). Planners estimated that five Skytram cars could deliver 110 persons to the meadow each hour; the shuttle car could deliver 110 persons to the upper terminus each hour. Water would be delivered to the meadow area in specially designed tanks carried by the cars. Sewage would be removed from the meadow landing in a similar manner. Electrical power available at Pine Springs was sufficient to power Skytram and power for facilities at the meadow landing would be generated by solar units. The estimated price for Skytram was $5,400,000. [18]

By early 1975, changing attitudes and concern with reducing park costs caused the Department of the Interior to place an unofficial hold on the tramway project. As a result, park Superintendent Donald Dayton faced a thorny problem. In January, Dayton met with Texas Congressman Richard White, the park's chief advocate in Washington. White was interested in developing a park that could be enjoyed by many of his constituents. In 1975 he had two objectives for the park: one, that legislation for the right-of-way exchange for the McKittrick Canyon access road be pushed through the next session of Congress, and two, that the tramway be constructed. Dayton did not tell White of the unofficial hold on the tramway project, but he indicated the opposition of the Sierra Club to the idea. White told Dayton that he would not support wilderness designation for the park until the tramway was constructed. He refused to support the wilderness plan because he believed the public had been cheated when plans for a ridge road between Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns were abandoned. White argued that he had worked to get the park authorized for the public to enjoy. He asserted that others, who had not been involved in the initial park effort, now were trying to dictate how the park would be used. [19]

Dayton knew that support for wilderness designation by the district's Congressman was essential to its adoption. The planners for the park were caught between the powerful forces of Congressional support and the environmental lobby. In March 1975, Dayton spoke at the National Park Service Regional Advisory Committee meeting in Carlsbad. He told the group, "The tram is controversial; we expect to get considerable opposition. But we feel we don't have much choice if the public wants to see it." [20]

|

| Figure 17. The proposed tramway between Pine Springs and Guadalupe Peak (from Guadalupe Mountains National Park Tramway study, undated) |

In the summer of 1975 the Park Service adopted an innovative approach to put the question of the development at Pine Springs to the public: a survey of opinions of visitors to Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns. Visitors answered a questionnaire offering six alternatives to future development at Pine Springs. The alternatives included a choice of maintenance of existing temporary facilities and five other choices, all of which involved development of a visitor center, maintenance shop, and employee residences, but offered different forms of transportation into the interior of the park: (1) an aerial tramway, (2) phased development with eventual construction of a tramway, (3) a helicopter shuttle, (4) a shuttle-bus road, (5) horse and foot trails. Exhibits and relief models helped visitors understand and evaluate the alternatives. Park planners hoped that the public opinion survey would provide input from park users, a group not usually represented at public meetings and workshops. Between July 18 and August 17 approximately 7,200 visitors responded to the questionnaire. [21]

At a public meeting held in Carlsbad in November 1975 to discuss the Pine Springs development, park officials revealed the results of the visitor survey: 2,321 visitors chose the alternative offering only foot and horse trail access to the high country; 2,165 chose the tramway alternative; 1,069 chose the shuttle bus alternative; lesser numbers of visitors selected the other three alternatives, with the phased development and helicopter alternatives receiving the least support. At the Carlsbad meeting, 26 speakers were in favor of the tramway while 11 were opposed. [22]

The following day Park Service officials held another public meeting in El Paso. The majority of the 86 persons who attended were not in favor of the tramway. [23]

Apparently, expressions of public opinion at the park and in his district swayed the support of Congressman White for the wilderness designation. In January 1976, while touring his district, he told a group assembled in Van Horn that while he opposed designation of the entire Guadalupe Mountains park as wilderness, he did think delicate ecological parts of the park should be protected, while leaving other areas open to the public. He made no remarks for or against the tramway. [24]

In September 1975 park managers completed the Environmental Assessment for the Pine Springs Development Concept Plan and a year later the plan was approved by the Southwest Regional Office (see Figure 18). The plan for visitor development provided for the possibility of a tramway but did not focus on it, using terminology such as "if and when a tramway . . . is constructed." [25]

According to the Pine Springs Development Concept Plan, the visitor center complex at Pine Springs would cover some five acres. Developments included the visitor center, which would comprise approximately 9,100 square feet, a possible food and sales concession, visitor parking, the temporary primitive campground, a future walk-in campground, and a possible future tramway terminal. The Pinery stage station would be accessible by a trail from the visitor center and would be interpreted. Another trail, simulating the route of the Butterfield stage, would lead from the visitor center to the vicinity of the Frijole ranch house. The springs, military encampment, and Indian sites near the visitor center also would be interpreted [26].

The Frijole ranch house and outbuildings, the nearby springs, and the old schoolhouse would be interpreted as a typical early ranch development. The horse concession would be located between the Frijole site and Highway 62/180. All horse trails would originate there. The meadow, reached by hiking trail, would have a shelter and vault toilets. Horseback and foot trails would lead to Guadalupe Peak. The plan provided for a future drive-in campground of 15 acres if private enterprise did not construct one in the vicinity of Pine Springs. [27]

Development for management in the Pine Springs area included separate maintenance and residence areas for the park service and the highway department on the south side of Highway 62/180. In 1987, Donald Dayton recalled the problems involved in choosing sites for both the visitor center complex and the maintenance and residence buildings. Because park boundaries had been dictated by property ownership lines rather than by the lay of the land, only a small buffer zone existed between the valuable visual resources of the park and its boundaries. The small amount of land available between the park boundary and the escarpment in the vicinity of Pine Springs severely limited the locations available for development. Environmentalists, concerned with maintaining the impact of an unobstructed view of El Capitan and Guadalupe Peak from the highway, lobbied for locating the residence and maintenance areas south of the highway. [28]

The Development Concept Plan also provided for utilities. Water for the entire Pine Springs area would be supplied from a newly drilled well, which was completed in March 1976. Above-ground electrical lines to the Frijole ranch house would be maintained to preserve historical accuracy, but all other electrical and telephone service lines would be underground. A sewage treatment plant would be located east of the Park Service residential area. The total estimated cost for buildings and utilities for Pine Springs was $5,110,000. Planners estimated an additional $2,510,000 as the cost for roads and trails. [29]

|

| Figure 18. Developments approved in 1975 for the Pine Springs area. |

The Regional Director approved the Master Plan for Guadalupe Mountains a month after approving the Pine Springs Development Concept Plan. An errata sheet attached to the plan stated that the decision on the tramway had been deferred because of "grave concern on the part of many interested persons, uncertainties of visitor use and demand in the immediate future, much more pressing needs for other facilities, and the current national economic situation." [30] That cryptic sentence summarized all of the opposition to the tramway: the concern of the environmentalists with preserving pristine wilderness, the change of attitudes within the Park Service and the Department of the Interior about what experiences the nation's parks should provide, and Congressional concern with reducing expenditures in the parks.

Other Plans for Development

Environmental Assessment for McKittrick Canyon

In 1975, the government acquired the right-of-way for a new access road to McKittrick Canyon. Construction of a new road, which would make the canyon much more accessible to visitors, made the need for visitor facilities in the canyon more imperative. The Master Plan provided for the road, as well as a parking area, and information and ranger station with a shaded waiting area. During 1976, staff at the Denver Service Center completed the Environmental Assessment of the buildings and utilities for McKittrick Canyon. The Environmental Assessment was necessary to determine how the comfort station and utilities could be developed. Under existing conditions, an aerial power line served the Pratt cabin, but there was no comfort station, water, or telephone available for visitors. Besides no action, three alternatives were proposed for the utilities for the ranger station and comfort station. All of the alternatives included electrical and telephone systems; two also included sewage treatment and water systems, the primary difference between the two being the type of sewage treatment provided. [31] The Environmental Assessment merely described the alternatives and made no recommendation about which should be adopted. Planners subsequently adopted the alternative that utilized a septic tank and leach field.

Upper Dog Canyon Development Concept Plan and Environmental Assessment

After 1975, the only way visitors could reach Dog Canyon was by using the trail system from other parts of the park. Automobile access to Dog Canyon, in the northern part of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, had been closed by landowners who refused to allow park visitors to travel across their property. Negotiations between the landowners and numerous government agencies were prolonged until 1977 when Eddy County acquired the necessary right-of-way and agreed to cooperate with the State of New Mexico to build a road to the park boundary. Planning for development near the northern boundary of the park progressed rapidly after road access to the canyon had been assured. While the Master Plan had provided for a ranger residence, contact station, primitive campground, and corral for park stock in Upper Dog Canyon, development of the area hinged upon the location of a dependable source of water for the residential area and for Park Service livestock.

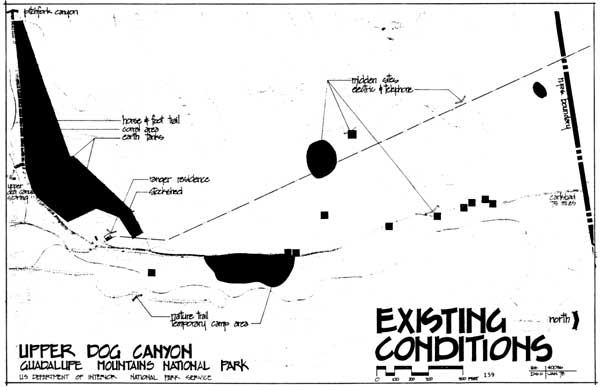

Before the federal government acquired the land from J.C. Hunter, Jr., the Laurie Kincaid family had lived at the Upper Dog Canyon site, in a house built a number of years earlier by Fred Cox. In 1976, the park ranger lived in the old house. Existing structures that dated from the 1930s included the house and a stockshed; more recent structures included two fiberglass water tanks and a metal storage shed (see Figure 19). Other facilities present in 1976 included a horse corral, a fenced pasture, a fire circle, a pit toilet associated with the temporary camping area, a weather station, and two earthen tanks that had been used for stock water storage prior to establishment of the park. Several midden sites, one deemed eligible for nomination to the National Register, were associated with the development area. The area also contained a one-mile nature trail and trailheads leading up Dog Canyon to Lost Peak and Pitchfork Canyon. Water for the ranger residence was obtained from Upper Dog Canyon Spring, which flowed weakly at 0.3 gallons per minute. A septic tank provided waste treatment for the residence. Electric power and telephone service, with frequent interruptions, were supplied from El Paso Gap, via Dell City. [32]

The Environmental Assessment for development of Upper Dog Canyon, completed in April 1978, expanded on the scheme that had been set forth in the Master Plan. The Environmental Assessment offered three alternatives besides no action. All three provided for the demolition of existing structures and replacement with residential and barn/storage units meeting park service standards. In each of the alternatives the residential area contained a three-bedroom residence with garage for the park ranger. The ranger's residence was combined with the contact station. The residential area also included two two-bedroom apartments for seasonal employees, with a garage for each residence. In each of the alternatives, the barn and corral complex was located at the south end of the developed area, in the vicinity of the existing stockshed. To provide water to the residences and for emergency visitor use, each alternative called for drilling a deep well and, if the flow justified development, construction of a 20,000-gallon storage tank, and purification and distribution systems. If the drilling effort failed to produce a sufficient supply of water, the existing water source, Upper Dog Canyon Spring, would be renovated and augmented with roof catchment and surface runoff collection. If necessary, supplemental water would be trucked to the area. [33]

|

| Figure 19. Conditions existing in the mid-1970s at the Dog Canyon development site. |

Each of the three alternatives involved 9.5 acres of land and varied only in the locations of the residential and campground areas. [34] One alternative placed the campground just inside the park boundary on the east side of the entrance road. The residential area was also on the east side of the road, between the campground and the barn area. A second alternative was similar to the first, but placed the campground on the west side of the road and nearer to the residential area. The third alternative placed the residential area west of the road, nearer the park boundary, with the campground on the site of the existing camping area. Each alternative had impacts on visitor use and experience, management, aesthetics, and the archeological resources present at the site. The estimated cost for the first and second alternatives was $613,000. The cost for the third alternative was $10,000 more because of an additional structure needed to cross the drainage channel to the residential area. The Environmental Assessment did not recommend any particular alternative but merely pointed out the advantages and disadvantages of each. Park managers ultimately selected the third alternative.

Statement for Management

In 1970, Neal Guse, Superintendent of Carlsbad Caverns, wrote the first Statement for Management for Guadalupe Mountains National Park. Guse defined the primary purpose of the park to be the preservation of geologic, scenic, and other natural values. Visitor use would be directed primarily to educational and inspirational experiences, while outdoor recreation values would be subordinate. Guse recognized the fragility of the Bowl and McKittrick Canyon. However, he also noted the importance of the view from Pine Top Mountain, a view that would enable visitors to understand the relationship of the park to its setting and, therefore, should be available to all. Development of the highly visible areas around Frijole and Pine Springs would need much care. Guse suggested that because the park contained no pre-existing tourist facilities planners had an unusual opportunity to develop facilities that would be most in line with the wilderness values of the park. [35]

Donald Dayton, the first Superintendent after establishment of the park, updated the Statement for Management during 1976, providing more information about the current situation in the park. Changes since the 1970 statement included the pending designation of 46,850 acres of the park as wilderness; acquisition of the right-of-way and scenic easements for an access road on the west side of the park; condemnation of the Glover property and Bertha Glover's continuing right to life-occupancy; the recommendation of areas in North McKittrick, South McKittrick, and Devil's Den canyons as research natural areas; and the adoption of a memorandum of understanding between the Park Service and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department requiring cooperation between the two agencies in wildlife management. [36]

Dayton's Statement for Management noted influences that had an impact on the park. Among the influences outside the park, he included hunting and predator control, especially control of mountain lions. Influences within the park included steady increases in visitation, with backcountry use being up 31 percent in 1975. Heavy backcountry use dictated the need for trail planning, with special consideration given to flash flooding during the summer, extreme wind conditions, and water sources. [37]

Dayton expanded the management objectives for the park. In addition to preserving the resources of the park and providing an educational and interesting experience for the visitor, he wanted to encourage continued research and to provide for development and maintenance of facilities. He also saw the need to promote harmonious interaction with neighboring landowners, federal and state agencies, and regional community organizations. [38]

Interpretive Plan

During 1976 a team of persons from the park and the Harpers Ferry Center developed the Interpretive Plan for the park that received Regional approval in February 1977. The plan identified the four themes to be interpreted--geological, biological, historical, and scenic--and the significant features of the park upon which interpretation would focus--the forest in the Bowl, McKittrick Canyon, El Capitan, and the Guadalupe escarpment. Development of the themes would be provided through interpretation at the visitor center, and with on-site programs, including self-guided tours of McKittrick Canyon, Williams Ranch, the Frijole Historic Site, and the Pinery Stage Station. With abandonment of the tramway proposal, planners estimated that 80 to 90 percent of the visitors to Guadalupe Mountains would never see the "island in the sky," the metaphor commonly applied to the Bowl area. As a result, the planning team recognized the heavy burden of interpretation that media presentations would have to bear. [39]

The Interpretive Plan described the interpretive center to be built at Pine Springs. The entrance area of the center would be a "visual gift" to the visitor, providing strong visual impressions of the parts of the park that most visitors would not see. Inside, the lobby area would provide a place for contact with park personnel and exhibits for orientation and information. Publication sales, restrooms, and a topographic relief map of the park would also be available in the lobby. In a separate audio-visual and auditorium area the primary media event of the center would take place, a 10- to 12-minute film designed to create the mood of the park and to present an impressionistic view of the ecological relationships found there. The exhibit room would contain exhibits relating to the geological, biological, and historical themes of the park, all of which would be unified by an emphasis on the importance of water to the park lands and to the people who had used them. Another separate area would be devoted to the backcountry registration and information center, where visitors could learn of the physical and logistical requirements of backcountry travel. Special publications related to the backcountry experience also would be sold in this area. From the interpretive center, visitors would be encouraged to walk to the Pinery along the trail, self-guided by a folder and wayside signs. [40]

The staffed contact station at McKittrick Canyon was also part of the interpretive plan. Exhibits and personnel there would provide information, orientation, and protection for the area. A sheltered, open-air space associated with the contact station would have six to eight wayside exhibits highlighting the unique biological and geological components of the canyon. A three-minute videotape would emphasize the fragile nature of the ecosystem of the canyon, while the ranger, through personal contact, would make apparent the ecological reasoning behind the rules to be observed while in the canyon. A single folder would explain the nature trail and geology trail which would originate at the contact station. A more detailed self-guide to a day-hike in the canyon would also be available. Trail markers keyed to the folder would mark points of special interest. [41]

Less formal interpretation would take place at the Frijole ranch site and Dog Canyon. At the Frijole site, a footpath marked with wayside units would lead to Manzanita and Smith springs. Interpretation would correlate settlement patterns with the water resources. The Dog Canyon ranger station would provide personal contact and orientation exhibits. A self-guided interpretive trail near the station would identify flora and natural features. [42]

Guadalupe Peak and the meadow below it would provide opportunities for the visitor to see the surrounding Chihuahuan desert and to identify distant landforms. All interpretive items would be located in the meadow shelter area, including a topographic orientation display panel as well as panels relating to the history of the park, geology, and flora and fauna. [43]

From the Pine Canyon primitive campground, a self-guided "discovery" trail with an accompanying publication would allow visitors to identify the sites of a military encampment, prehistoric middens, and the remains of an early dugout. Campground activities would include a self-guided nature walk, a campfire circle, and an outdoor amphitheater with a screen for evening audio-visual presentations. [44]

Along the road planned to traverse the west side of the park, wayside exhibits would mark points of interest. A roadside pull-off that provided an unobstructed view of Williams Ranch would contain an exhibit interpreting the transition in settlement patterns, from dugout to frame house construction. A wayside exhibit at another pull-off area would identify and locate the salt flats west of the park and interpret their historical significance for the region. Secondary wayside pull-offs would provide interpretation of the skyline of the western escarpment, a Butterfield stage crossing, the red sand dunes, the gypsum sand dunes, and the grave of Jose Maria Polancio. [45]

The Interpretive Plan also provided the Collection Management Statement for the park. Included in the Statement were policies for collection and storage of biological and geological specimens, collection and loan of archeological objects, collection of historical objects needed to furnish the ranch houses, collection of art and photographs relating to the interpretive themes of the park, and the storage and evaluation of "cultural debris" found in the park. [46]

The plan identified several new publications that were needed to aid in interpretation. One was a natural history handbook serving both Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns. A backcountry hiker's guide also would serve both parks. The third publication needed immediately was the self-guide folder for McKittrick Canyon. Self-guide folders for Dog Canyon, Pine Springs, and the Pinery were already available. The plan also set out research priorities related to interpretation, including a determination of the scope of collections for the archeological resources of the park, increased information about the native Indian cultures found in the park, and more detailed research to establish the contribution and significance of the historic resources of the park. [47]

Resource Management Plans

Throughout the 1970s a number of plans for resource management were initiated. Most were very general, providing little more than recognition of the variety of natural and cultural resources of the park, the imperative need for research to document and evaluate those resources, and reiteration of the commitment of management to preserve and maintain the existing situation until research could be completed. However, these plans provided a baseline for the extensive refinements that would take place in the next decade as well as management guidelines for the interim.

In 1973, under a contract with the Park Service, researchers from Texas Tech University began an ambitious program to collect basic resource data. The contract, which was in effect for some eight years, called for a multi-disciplinary approach to data collection, covering botanical, geological, historical, climatic, wildlife, and water resources.

Cave Management

The first official Resource Management Plan for the park related to cave management, reflecting the close relationship of Guadalupe Mountains to Carlsbad Caverns. The plan, adopted in 1972 and written to cover both Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains, set forth a method for identifying, describing, and classifying new caves, and noted that this system would also be utilized by the Forest Service for caves within the Lincoln National Forest and on adjoining lands under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management. Caves would be classified in two ways, one for hazard level and the other for significance of formations within the cave. On the ground, caves would be identified with a brass cap set at the cave entrance, giving the cave number and the name of the federal agency responsible for the cave. Cave locations would not be disclosed to the public except at the discretion of the park superintendent. Although management intended full cooperation with caving groups and researchers, no one could enter caves without prior written permission from the superintendent. [48]

Backcountry Management Plan

Guidelines for management and visitor use of the backcountry were among the most pressing administrative needs during the early years of operation of Guadalupe Mountains National Park. Late in 1973, some five years before the park obtained official wilderness designation, the first Backcountry Management Plan was approved. The primary objective of the plan was to provide maximum visitor enjoyment, but with three limitations, the first of which was most important: (1) activities that would not incur irreparable damage to the resource, (2) activities appropriate to a Park Service natural area, and (3) considerations of sociological factors associated with numbers of people using the backcountry. [49]

During the second year of operation, visitation at the park increased 44 percent and backcountry use increased 82 percent. According to observations by park personnel, most visitors entered the park from the Frijole and Pine Springs areas and use was concentrated in the southern half of the park. Because hikers had to carry their own water, most trips into the backcountry did not exceed two days. Sixty miles of trails existed in the high country and McKittrick Canyon, all of which had been established as ranch roads and stock trails. Except for the trails up the escarpment, which were rocky, narrow, of steep gradient, and subject to erosion, most trails were located in stable areas. Although 80 percent of the trails were open to horseback riders, few visitors used horses. The existing trails circumvented the 150 identified archeological sites in the high country, and since none of the sites was spectacular or contained formal structures, no active protection of them appeared to be necessary. A number of historic resources also existed in the backcountry, including portions of the Butterfield stage route, Williams Ranch, Marcus Cabin, and some old mine tunnels. Planners recognized that treasure-hunting might create a management problem in the backcountry. [50]

The Backcountry Management Plan outlined research needs. Planners gave first priority to determining the carrying capacity of the backcountry. Data obtained from ongoing research conducted by Texas Tech in the areas of biology, mammology, archeology, and aquatic life would be utilized, and a range-analysis survey was proposed. Transects would be established along trails and read regularly to observe the impact of visitor use on vegetation and erosion. Patrols would be instructed to observe and report on the accumulation of litter, sanitation conditions at campsites, the occurrence of illegal fire rings, and the impact of horse use in the backcountry. Records would be maintained of trail usage by day-hikers, overnight use, transect and patrol observations. Questionnaires and personal contact with local organizations would be utilized to solicit public opinion about facilities and visitor experiences. [51]

The management plan addressed five areas where improvement was needed in order to effectively handle or increase carrying capacity of the backcountry: trails, campsites, horse use, water guzzlers, and a patrol cabin. Staffing and funding increases would be needed so that a trail maintenance program could be begun. Three new campsites would be designated. Future identification of alternate campsites would allow the establishment of a rest-rotation system for campsites. Non-intrusive sanitation systems for backcountry use also would be investigated. During 1973 two changes had been made to accommodate horseback visits to the backcountry: a corral was established on the west side of the park to allow a trip longer than one day for visitors on horseback, and under the provisions of a special-use permit, a local rancher offered one-day trail rides to visitors. The plan suggested exploring the potential of water guzzlers (a mechanical system involving catchment and controlled release of water) as a water source for the backcountry. While a log cabin in the Bowl, predating establishment of the park, served as a patrol cabin and fire cache, planners recognized the need for a new site and cabin that could be serviced by park livestock, probably along the main trans-park trail. [52]

Another concern expressed in the Backcountry Management Plan was for the removal of human-made intrusions from the backcountry. An inventory of such structures was underway and priorities for their removal would be established. [53]

In the interest of improved public relations, the management plan proposed to use the media and printed handouts to inform the public of policy or backcountry problems. Additionally, public appearances by park staff at meetings of local organizations would provide better public understanding of the park's backcountry policies. Finally, the management plan listed funding and personnel necessary to carry out the programs outlined in the plan. [54]

Natural Resources Management Plan

In January 1975, a Natural Resources Management Plan, incorporating the earlier Cave and Backcountry Management Plans and a new Fire Management Plan, was approved. Management objectives for visitor use were the same as those presented in the Statement for Management written in 1970, generally, that all visitors should have convenient access to the top of the escarpment, the Bowl, and McKittick Canyon; that the geologic, biologic, and historic resources of the park would be interpreted; and that park resources would be available to students and researchers. Resource management objectives were also similar to those outlined in the early Statement for Management: designation of research natural areas in North and South McKittrick Canyons and the Bowl, protection of moisture-loving plants found within the park, cooperation with the Forest Service to manage North McKittrick Canyon, use of fire as a management tool in the Bowl area, protection of the open landscape from visual intrusions and destruction of vegetation, restoration of wildlife habitat, including reintroduction of the desert bighorn and Montezuma quail, and protection and evaluation of archeological and historical resources. The plan also repeated the land classifications set forth in the Master Plan. [55]

The Natural Resources Management Plan also enumerated actions necessary to meet management objectives. Several of the actions would continue existing research programs: monitoring the quantity and quality of the water sources in the park, maintaining and reading elk and deer transects, conducting big game browse surveys, and monitoring the forests for insects and disease. However, much new research also was needed, including inventories of vascular and non-vascular plants, fauna, micro-organisms, significant geological features and processes, soils, and hydrologic features. At the time of the publication of this plan, the tramway was still a possibility; therefore, another research priority was a climatological study of the entire park, but especially to learn of wind velocities in the canyon where the tramway would be located. Planners identified another much- needed management tool, a soils map, and proposed that one could be created after completion of the soils inventory and analysis. Fire management also was a major concern; the plan proposed research to determine the extent to which the forests of the Guadalupe Mountains depended upon fire to retain their natural state. Studies to determine the impact of large ungulates and other fauna on the environment also were needed. The planners realized, however, that accumulation of data was not enough; the data must be available to management in a usable form. Therefore, they recommended the use of a computerized data management system. [56]

Guidelines for fire management also were important to management of the park's resources. The Fire Management Policy established in 1975 revised the previous policy to suppress all fires. The new plan proposed to allow all naturally-occurring fires in the low desert country to run their course within the limits of designated burning units. However, within the designated burning units full control would be exercised over fires occurring near park boundaries and near the boundaries of the reef formation. All human-caused fires would be suppressed. The plan proposed to initiate research to investigate the potential effect of natural wildfire on the interior mountain and canyon country, specifically on the relict plant communities. After completion of the research, the designation of other areas as natural burning units would be considered. Until research was completed, however, comprehensive control would be exercised. Continuous observation would take place to detect fires and to monitor the progress of fires within natural burning units. Data would be maintained on all fires, including cause, weather, size, vegetation, and burning behavior and follow-up investigations would be conducted to determine the recovery rates of vegetation and the effects of fire on undesirable vegetation types. [57]

Although the Natural Resources Management Plan apparently was intended to be a comprehensive document that included recognition of the need to manage the cultural resources of the park, the plans for management of historic and archeological resources were cursory. The Archeological Management Plan referred to "An Inventory and Interpretation of Prehistoric Resources in Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Texas," by Susanna R. and Paul R. Katz, published in December 1974 under a Park Service contract, but identified it as "a documentation of archeological values, not a management plan." Similarly, the Historical Management Plan consisted of a reference to "A Survey of Historical Structures of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Texas," by Texas Tech University, College of Agricultural Science, Department of Park Administration and Horticulture, published in September 1973 under a National Park Service contract, also a "documentation of values." [58]

Trail Planning

The trail system at Guadalupe Mountains National Park was one of only a few in the park system completely designed and built by professionals. [59] Beginning in 1977, two consultants planned the permanent trail system for the park. Jack Dollan, a Wilderness Manager on loan to the Park Service from his Forest Service position in the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana, began the project. He spent weeks hiking the backcountry, determining how trails could be located or relocated to make the least impact on the land and provide a safe but exciting route for hikers. Originally, park planners intended that Robert Steinholtz, Landscape Architect with the Denver Service Center of the Park Service, would take over the trail planning when Dollan returned to his regular position. However, in 1978 Dollan transferred to the Denver Service Center and he and Steinholtz worked together to finish planning the trails for the park. Phil Koepp, who became Chief Ranger of the park in 1981, worked with the two men during the latter phases of construction of the trails. In 1987 he recalled how the viewpoints of the two men were complementary; while Steinholtz was an engineer, Dollan enjoyed the thrill of exploring wilderness areas. [60] The trails they designed reflected those interests. Roger Reisch, Park Ranger at Guadalupe Mountains since 1964, also remembered Dollan's work: he designed trails to keep hikers in suspense until they reached their destination, hiding magnificent views until the last breath-taking moment. Reisch also noted that Dollan and Steinholtz tried not to exceed a 10 to 11 percent grade on any trail. [61] By 1979 more than 80 miles of trail construction and reconstruction had been planned. The work was planned to be completed in four phases.

The Contribution of Donald Dayton

Donald Dayton played an important role in the administrative history of Guadalupe Mountains National Park. As Superintendent of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains from 1971 to 1981, he guided the parks through the difficult processes of master planning and wilderness evaluation. Dayton entered the Park Service in 1955; by 1964 he had become a park superintendent. His career had matured during the development-oriented time of MISSION 66. By the early 1970s, however, the precepts that had guided park managers during the 1950s and 1960s were eroding. As Dayton directed the planning process for Guadalupe Mountains, not only did he have to deal with public protest against Park Service plans, but he also had to adjust to new attitudes brought about by the change of administration in Washington. Further, Dayton had to achieve a workable balance between the opposing points of view of the park's principal advocate in Congress and the environmental lobby. Finally, Dayton faced the frustrations of a bureaucrat: the master planning process itself was in a state of flux. Legislation passed two years after the Master Plan for Guadalupe Mountains was finally approved made it obsolete.

In addition to planning for development, Dayton guided the formulation of the basic plans for wilderness backcountry use and resource management for the new park. While these skeletal plans recognized the need for research in many areas, they provided the premises on which all future planning would be based.

Dayton's work required patience, flexibility, and an enduring belief in the democratic process. Unlike a corporate manager, he could not make planning decisions based on his past professional experience. Instead, he and other Park Service officials had to seek public consensus about uses of the park, then plan for those uses within the parameters established by the Department of the Interior and Congress.

At the close of the 1970s, major development planning and the environmental reviews associated with the plans had been completed. Visitor facilities, housing for personnel, and the trail system were under construction. Park managers, with input from the public and other government agencies, had decided what kind of park Guadalupe Mountains would be. In his book, Mountains Without Handrails, Joseph Sax discussed the abandonment of the tramway at Guadalupe Mountains. His attitude represented the attitude of the environmentalists who had helped to defeat the tramway proposal. Sax said, "Peering at a wilderness from a tramway station. . . is not a wilderness experience; the sense of wilderness is not achieved by standing at its threshold, but by engaging it from within. Not everyone will seize the chance to experience wilderness, even in the modest dose that Guadalupe Park represents. The opportunity can and should be offered as a choice, to be accepted or rejected; but it should not be falsified or domesticated." [62] Environmental and financial concerns had determined that Guadalupe Mountains would be a wilderness park. It would appeal primarily to hikers, backpackers, and researchers who were willing to accept the land on its own terms.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

gumo/adhi/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 05-May-2001