|

Guadalupe Mountains

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter VII:

PLANNING IN THE 1980s

Planning continued in the 1980s. Park managers considered adding more land to the park, but in most cases, the plans that management adopted were revisions or more detailed versions of earlier plans rather than being totally new concepts. With planning for development nearly complete, planning for preservation of the natural and cultural resources of the park became the highest priority. Ralph Harris, the Area Manager of the park from 1981 to 1987, suggested that prior to 1984, when the first full-blown resource management plan was approved, management decisions often had to be made as individual problems occurred. Running a park that was in a reaction mode rather than an action mode made the job of the area manager hectic and frustrating. [1]

Economic Feasibility/Market Study

The Concessions Management Branch of the Professional Support Division at the Denver Service Center studied the feasibility of establishing a horse concession, a camper/hiker store, and a food service at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. A random sample survey of visitors, taken between January and August 1980, provided some input to the study, as well as comparison with similar concessions at Big Bend National Park. None of the surveys developed for the study showed that concessions would be economically viable at that time. [2]

Master Plan Supplement

In 1980 park planners initiated a study to investigate the possibilities of revising the boundaries of the park and to provide a Development Concept Plan for the west side of the park. In the House Committee Report accompanying P.L. 95-625, the law that gave wilderness designation to 46,850 acres in Guadalupe Mountains National Park, committee members asked that the park's west side land be re-evaluated for wilderness designation after development plans were complete. Therefore, in compliance with the House request, the Master Plan supplement also made recommendations regarding increasing the amount of land in the park that was designated as wilderness.

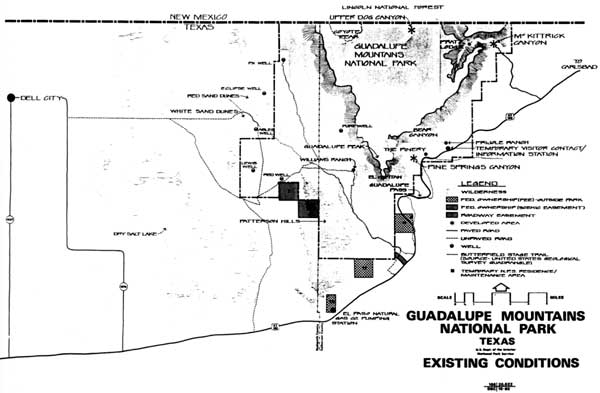

Planners considered three locations for boundary revisions. One, on the west side of the park, involved acquiring approximately 9,500 acres of red quartoze and white gypsum sand dunes immediately adjacent to the park's western boundary. The second location included several areas along U.S. Highway 62/180 that had been designated as part of a "critical scenic preservation zone" in the Master Plan approved in 1976. Since the plan did not provide any means of retaining the scenic qualities of the zone, the study undertaken in 1980 addressed whether any boundary expansion was needed in those areas and, if expansion were necessary, what type of ownership or control would be most appropriate. The third part of the boundary study included the disposition of two sections on the west side controlled by a scenic easement. [3] It also included consideration of two and one-half sections of land outside of the park boundary that had been acquired for trade purposes at the time of the purchase of J.C. Hunter, Jr.'s, property but had not been used and were still owned by the federal government. Figure 20 shows the conditions existing in 1980 and the areas affected by the proposed boundary revisions. [4]

Besides no action, the Environmental Assessment for the Master Plan supplement provided four alternatives for development on the west side of the park. The alternatives proposed varying levels of resource protection, facility development, wilderness designation, and different locations for the access road and facilities. The Environmental Assessment and Master Plan supplement were available for public comment from December 1980 to February 1981. During this period, park officials received 72 letters and a petition related to the plan. Three persons attended a public meeting about the plan held in Carlsbad on January 14, 1981. A similar meeting, held the next day at a location near the park, drew about 85 persons. Local citizens who expressed opinions generally were opposed to any form of land acquisition, either in fee or easement, unless the landowner was willing. However, many local people were in favor of an improved road connecting Dell City with the west side of the park. Park visitors and representatives of conservation organizations favored the alternative that proposed acquisition of the entire sand dune area in fee, as well as acquisition in fee of an area near Guadalupe Pass and a scenic easement near McKittrick Canyon. This alternative did not include a road between Dell City and the west side of the park and proposed the addition of 33,200 acres to wilderness designation. [5]

Congressman Richard White supported the suggested boundary revisions and the development of visitor and administrative facilities on the west side of the park; however, in a conversation with Donald Dayton in August 1980, he indicated strong opposition to additional wilderness. Reminding Dayton that he had gone along with what to him seemed to be more than adequate wilderness in the original legislation, he was unwilling to support an addition, especially in the vicinity of Pine Canyon. Although he realized the tramway was a "dead issue," he believed that the focal point of visitor interest should not be under the restrictions of wilderness designation. He also indicated his unwillingness to cooperate with environmental groups that "keep coming back for more" every time Congress approved wilderness legislation. [6]

|

| Figure 20. Existing boundaries and non-park sections as of 1980. |

West Side Boundary Study

In August 1981, because of changing policies and funding constraints, Interior Secretary James Watt indefinitely postponed the proposed park expansion. In 1985, however, the possibility of acquiring the red and white sand dunes was revived. The landowner who controlled the major portion of the sand dunes area contacted the Department of the Interior and offered to exchange his lands in the dune area for federal lands in another area or state. A new study was undertaken to update the work done in 1980.

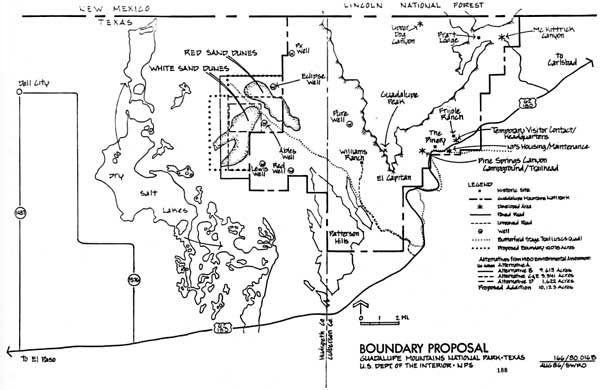

The area under consideration comprised 10,123 acres, somewhat more than proposed in the Master Plan supplement because it included the grasslands lying between the sand dunes and the access road. The area recommended as an addition to Guadalupe Mountains National Park included all of the red and white sand dunes, which have been identified as Texas Natural Landmarks (see Figure 21). Within the sand dune area were many unusual plant associations and rare species, one of which, scale broom (Lepidospartum burgessii), was eligible for federal endangered species status. The sand dunes also contained numerous archeological sites. The study pointed out that the west side of the park provided a good area for winter visitors. Temperatures were more moderate than in the Guadalupe Pass and high country areas, and in the spring, blooming wildflowers and less severe winds made the desert area especially appealing. A private landowner had donated the right-of-way for a road to be built by Hudspeth County connecting Dell City with the park boundary, south of the main dune field. The county consulted with park managers and officials from the regional office before selecting the route for the road. [7]

Resources Management Planning--1980s

During the 1980s park planners also refined and expanded the Resources Management Plan. The plan written in 1982 and approved in 1984 outlined a five-year program of actions; in 1987 the five-year plan was updated and new priorities were established. The plan written in 1982 included extensive refinements in planning for management of natural resources, as well as revised cave and backcountry plans and a Cultural Resources Management Plan. Management objectives set forth in the new plans remained virtually unchanged from those expressed in the Statement for Management written in 1976.

|

| Figure 21. Boundary expansion proposed for west side of park in 1987. |

Development of new monitoring programs received much emphasis in the plan of 1982. The plan recommended programs associated with fire management, backcountry use, cave protection and use, the preservation of McKittrick Canyon,utilization of vegetation by ungulates, and oil and gas development. Other programs included monitoring the surface water resources of the park, and monitoring threatened and endangered species found in the park, particularly the peregrine falcon. The encroachment of Barbary sheep on park lands and trespass grazing by livestock from nearby ranches were two other problems needing documentation. Along with documentation and monitoring of resources, the management plan reiterated the continuing need for an information retrieval system to make the accumulated research data useful. [8]

The Natural Resources Management Plan reflected new concerns for wildlife in the park and included plans for reintroducing two native species, the desert bighorn sheep and the Montezuma quail. Control of non-native species, particularly Rocky Mountain elk and Barbary sheep, was identified as a management objective. The plan also addressed the park's mountain lion population, an issue that required extensive attention from management during the 1980s. In conjunction with monitoring the mountain lion population, resource managers recommended monitoring the mule deer population; both populations had increased with park protection and were interdependent. The plan also reflected the continuing concern of management with the water resources of the park. Water resources limited the ungulate population of the park and were affected by visitor use, park development, and external influences. [9]

Park planners recognized that designation as a national park and federally protected wilderness did not erect an impermeable barrier around Guadalupe Mountains National Park. In fact, those designations laid a heavy burden on park managers to be constantly alert to obvious and insidious outside influences that might harm the resources they were mandated to protect. By 1982, managers were more aware of the extent of external influences on the park than they had been a decade earlier. Oil and gas development in the area, ranching and hunting activities, regional pesticide use, and industrial activity in El Paso, Texas, and Juarez, Mexico, all affected the resources of the park. Similarly, park planners were more aware of the need for cooperative efforts with other governmental agencies to manage such resources as the peregrine falcon, mule deer, and mountain lions; to cooperate in the reduction of Barbary sheep; to control harmful forest insects and diseases; to reintroduce native species; and to assure that oil and gas development did not adversely affect designated wilderness areas. [10]

The planning document listed priorities for management of the park's natural resources. The first five priorities, in order of importance, were to conduct studies of predator populations, to begin an affirmative management effort to improve communications with the neighbors of the park regarding predator populations, to rewrite the Backcountry Management Plan, to institute monitoring programs in the backcountry, and to revise the Fire Management Plan. [11]

Cave Management Plan

The Cave Management Plan, rewritten in 1981 and incorporated into the larger Resources Management Plan, contained objectives similar to the Cave Management Plan written a decade earlier: protection and perpetuation of the caves in the park, provision of recreational and educational experiences for visitors, provision of opportunities for scientific research, classification of caves into management categories, and the establishment of regulations and guidelines to ensure visitor safety and preservation of the resource. However, the new plan contained a major policy change: two wild caves in Guadalupe Mountains National Park would be opened, on a permit basis, to the public. An administrative system for reviewing permit applications would be established to ensure that visitors had the knowledge and experience necessary to handle the hazards and conditions of the cave they wished to visit. Another provision of the plan included monitoring of caves to document resource conditions under varying levels of use. In addition, park staff would receive more information about caving techniques, safety, first aid, speleology, and search and rescue. The public would be given more information about access routes, hazards, and permit requirements. New interpretive programs would be aimed at increasing public appreciation of caves. [12]

Backcountry Management Plan

By early in 1984 the much-needed revision of the backcountry management plan was in place. Because the first backcountry plan was written before the park acquired wilderness designation, policies relating to preservation of wilderness values were non- existent. The management objectives and policies of the new plan first addressed the needs of the wilderness resources, then the needs of visitors to the wilderness. Among the objectives outlined were restoring conditions conducive to the perpetuation of natural processes and native animal and plant life, particularly rare and endangered species. Land surfaces disturbed by humans would be returned to their natural appearances, but significant cultural values would be retained. [13]

Wilderness policies outlined in the plan were based on the premise that visitors must accept the risks of wilderness travel and the absence of modern conveniences. To protect the resource, campsites would be designated. At most, campgrounds would include a site marker, tent sites, and a pit toilet. Trail width would be limited to that required for single-file travel by foot or by horse. Research and data-gathering would be permitted as long as they did not modify the physical or biological processes and resources. Motorized or mechanical equipment would be used in the backcountry only in emergency situations. To protect the fragile water sources within the park, camping near springs and streams and wading and bathing in the streams would be prohibited. [14]

Plans for management of McKittrick Canyon included discontinuation of use of the Stone Cabin as a ranger residence. Power and water lines to the cabin would be removed but the restroom facilities for visitors would be retained. In the future, the cabin would serve as a cache for emergency equipment and as an administrative site. Although camping was not permitted in the part of McKittrick Canyon managed by the Park Service, camping permits for that part of North McKittrick Canyon lying within the Lincoln National Forest would be available at the McKittrick Canyon contact station. [15]

By 1984 the first three phases of trail construction in the park had been finished. As outlined in the backcountry management plan, Phase IV provided for rerouting and deleting some existing trails that were either unmaintainable or redundant; a total of 29.7 miles was affected. At the conclusion of Phase IV the park would have 66 miles of trails, a net decrease of 18 miles from the total in 1984. Forty-two miles of trails would be available for use with riding- and pack-livestock. Parties with livestock would be limited to 15 animals and to day-use only. Visitors using livestock would obtain a special permit from the park headquarters before entering the park. The Bowl would be closed to all livestock. [16]

Under the new Backcountry Management Plan, visitors needed permits to use campsites. The permits were free and issued on a first-come, first-served basis. At each campground, tent sites had been designated and planners intended that eventually all tent sites would be "hardened." No more than four persons, occupying one large or two small tents, would be permitted to camp at a tent site and for no longer than two consecutive nights at the same campground. Two backcountry campgrounds had pit toilets, installed on an experimental basis. In addition to the designated campsites, the management plan also established an "open" camping zone. Length of stay in the open zone also was limited to two consecutive nights and regulations required that the tent site be moved after the first night. Most campgrounds were approximately a half-day hike from backcountry entrance points. Open fires would not be allowed anywhere in the backcountry. Visitors would be expected to pack out all trash and would be advised of the regulations regarding disposal of human wastes before entering the backcountry. [17]

The management plan provided for some administrative facilities in the backcountry. A small patrol cabin near Pine Top had replaced the log cabin in the Bowl, which formerly had been used for administrative purposes. Caches of fire tools and water would be located strategically throughout the park. The radio repeater facility on Bush Mountain, consisting of an antenna and small shed would be retained. In the future a small helipad might be constructed to facilitate maintenance of the antenna. [18]

Wildlife management in the park favored the entire ecosystem rather than individual species. While no artificial facilities would be maintained for the benefit of specific wildlife types, the plan provided for affirmative management of two elements in the ecosystem: habitat for endangered species would be protected and enhanced and exotic species would be controlled. By 1984 three species known or believed to be endangered had been found in the park: the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum), Sneed's pincushion cactus (Coryphantha sneedii var. sneedii), and McKittrick pennyroyal (Hedeoma apiculatum). [19]

The planners also were concerned with the cultural resources that existed in the backcountry. In spite of the mandate that wilderness areas be free of substantial evidence of the presence of humans, other laws required that significant cultural resources existing on federal lands be preserved. Planners determined, therefore, that some of the human-made structures existing in the wilderness areas should be left as "discovery" sites, representative of the historic period of ranching, and allowed to molder away naturally. Generally, these structures included remnants of the intricate water system that had been established during the ranching era to maintain livestock and the elk population in areas where surface water did not occur. Among these structures were tanks and pipelines in Bear Canyon, the Bowl, and at Williams Ranch. Also, cabins near Lost Peak, in the Bowl, and at Cox Tank would be retained. Many other metal tanks and pipelines, fences, stock pens, and small buildings would be removed and earthen tanks breached. [20]

Signage in the backcountry was not standardized, was weathered, and sometimes inaccurate. The management plan proposed to replace all existing signs with anodized aluminum plates with standardized lettering, mounted on metal posts. Registers, topographic maps, and a place for posting weather conditions would be established at each trailhead. The number of interpretive signs in the backcountry would be minimal; instead, interpretation would be provided at the entrances to the wilderness area. [21]

Resources Management Planning--1980s (continued)

Cultural Resources Management Program

The Cultural Resources Management Plan also was a major addition to the Resources Management Plan approved in 1984. By that time, surveys of the archeological resources of most of the park were complete. The archeological surveys conducted in 1970, 1973, and 1976 identified seven periods of cultural history in the park, beginning around 8,000 B.C., but archeologists found no permanent prehistoric settlements. Researchers found archeological sites associated with every road and trail in the park, as well as in less-accessible locations. Twenty-nine of the 299 archeological sites that had been identified during the surveys were considered eligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. Artifacts most commonly found in the park included projectile points, stone tools, and pottery sherds. Although the surveys established a baseline for management of the archeological resources of the park, planners noted that site excavations were still needed. [22]

The inventory of historic resources of the park also had been completed and actions to protect the most significant structures had either been completed or were in process. The Pratt Stone Cabin and the Pinery Stage Station already had been accepted for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, but park managers still awaited decisions about listings of the Pratt "Ship on the Desert" Residence and the Emigrant Trail. A listing of classified structures within the park included those associated with the resources eligible for listing in the National Register as well as those associated with the Williams Ranch. Researchers classified other historic structures in the park as "discovery" sites that would be allowed to molder away naturally. [23]

The management plan contained a priority listing of projects related to the cultural resources of the park. The first five priorities were: compilation of cultural resource data, establishment of a professionally curated museum collection, archeological reassessments of high impact areas, preparation of Historic Structure Reports for the classified structures, and preparation of Historic Structure Preservation Guides for the classified structures. [24]

Fire Management Plan

Approval came in 1985 for the park's first comprehensive plan for fire management. Until approval of this plan all fires occurring in the park had been suppressed. Under the provisions of the management plan, naturally occurring fires would be allowed to burn without suppression unless they threatened park facilities, visitor safety, major resources, or park boundaries. Human-caused fires occurring during the natural fire season also would be permitted to burn within the above conditions. The plan proposed to continue research concerning prescribed burning as a management tool. [25]

Resources Management Plan Revisions, 1987

During 1987 park managers revised the Resources Management Plan. Priorities for management of cultural resources remained unchanged from those established in 1984. However, while some of the natural resource issues that were important in 1984 continued to be top priority items in 1987, some new issues dominated the list. In order of importance, the priorities established in 1987 were: fencing of the park boundary; implementing a prescribed burning program; funding of and equipment support for a new resource management position; implementing the earlier recommendations for backcountry management, such as hardening of campsites, removal of fences, and establishment of monitoring transects; and monitoring of predator populations in both Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns. [26]

Except for new priorities, the Resources Management Plan recommended in 1987 was little changed from the version written five years earlier. The list of endangered species found in the park contained a new addition: a hedgehog cactus found at lower elevations on the west side of the park, Echinocereus lloydii. A new emphasis of the plan was the need to construct or replace fences around the 63.25-mile boundary of the park. Only 18.25 miles of existing fence were adequate, 22.75 miles were unfenced, 8.0 miles of existing fence was in bad repair, and 14.5 miles of the boundary was fenced by old drift fences, which were not on park property. Trespass grazing by cattle and horses was a continuing problem between the Big Canyon and Bell Canyon drainages below the eastern escarpment as well as in the Guadalupe Canyon area, where boundary fencing in the area of Middle and Lower Guadalupe Springs was either nonexistent or in poor repair. [27]

Another new natural resource project recommended in the revised plan was monitoring and eradicating exotic plants growing within the park. While only a few plants of salt cedar (Tamarisk sp.) were found in the park, it was identified as an exotic species to be eradicated before it became well established. Salt cedar threatened the water resources of the park; plants growing near springs or in low places would dry up water sources with low flow rates. [28]

By 1987, completion of an extensive study of the mountain lion population in Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns National Parks allowed resource managers to revise some of the natural resource priorities established in 1982. In 1986 resource managers completed a plan for management of the mountain lion population in the two parks. The plan was based on the results of a three-year study, begun in 1982, to document the number, range, and feeding habits of mountain lions in the parks. The study included monitoring of a number of radio-collared lions to determine movement and dispersal of the animals, and scat analysis to determine food habits. The plan proposed four actions: (1) maintenance of existing protection of mountain lions within the two parks, (2) continuation of monitoring of mountain lion populations, (3) establishment of a program to monitor deer and elk populations, and (4) development of an inter-agency mountain lion task force. [29]

While the mountain lion issue was under better control, park planners recognized a new wildlife concern. Between July 1985 and June 1986, four black bears had been killed immediately outside the northern boundaries of the park, apparently the victims of the ongoing predator control program supervised by the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. In January 1987, the Texas Park and Wildlife Department placed the black bear on its state list of endangered and threatened species. Concerned that the black bear issue could become as sensitive as the mountain lion issue, park planners recommended the initiation of a monitoring program for the bears so that park officials could make well-informed responses to expressions of public concern. The planners also suggested positive action on the part of the park service that might foster better inter-agency cooperation in management of the bear population. [30]

Statement for Management

During 1987 planners at the park and at the Southwest Regional Office worked on a new Statement for Management, the first revision since 1976-78. The draft document available in June 1987 listed a number of changes in legislative and administrative requirements, including: (1) recognition of continued government ownership of the parcels of land outside the park boundaries; (2) designation in 1978 of 46,850 acres of park land as wilderness and re-evaluation of remaining park lands for wilderness designation in 1980; (3) recognition of the need to preserve natural research areas in unmodified states because of the rare, endangered, or endemic species existing there; (4) recognition of the existence of several special use permits, allowing park land to be used for utility and right-of-way easements; and (5) establishment of concurrent law enforcement jurisdiction with the State of Texas. [31]

The Statement for Management also provided the names of 25 plants and animals found within the park that were listed or were under review for listing as endangered or threatened species. Among cultural resources, the Emigrant Trail was added to the previous list of historic resources deemed eligible for nomination to the National Register. [32]

The Statement for Management provided an analysis of visitor use, noting that the number of visitors to the park increased "dramatically" until 1981, after which a slower upward trend began. Planners suggested that the only limitation to greater visitor use was the lack of an adequate visitor center at the park. The inadequacy of the visitor center and the campground at Pine Springs reappeared again in the Statement for Management when resource issues were outlined. Other resource management issues identified were: (1) accumulation of data on plant and animal populations and air quality, development of floodplain studies, and consolidation of geological data; (2) the use of prescribed fire as a management tool; (3) construction of a boundary fence to exclude trespass grazing and exotic species; (4) determination of carrying capacity for the backcountry; (5) the possible addition to the park of the sand dune areas on the west side; (6) the need for increased funding to reevaluate, maintain, and preserve cultural resources; and (7) the need to finish trail construction, which was only about 50 percent complete. [33]

The draft Statement for Management also outlined issues related to administration and maintenance. Offices and administrative work space were inadequate, no facilities were available for visitor protection functions, an additional residence was needed at Dog Canyon, and the Pine Springs Cafe was being operated outside normal contract and permit procedures. [34]

Although management objectives were not exactly the same as those presented in 1976, they represented the same issues and concerns. However, a new management objective appeared in the draft statement. Planners recognized the need to provide handicapped accessibility to visitor facilities. Also, the Statement for Management emphasized that important aspects of the park's resources, especially the less-accessible high country and canyons, must be communicated to visitors who would not experience those resources personally. [35]

During the 1980s park managers and planners refined and enlarged planning documents related to the management of the resources of the park. The great body of research completed in the late-1970s and early-1980s helped park planners establish priorities for resource management. In the five years from 1982 to 1987 park managers made considerable progress in meeting priorities established for natural resource management. However, cultural resources received much less attention. During the five-year period, no cultural resource priorities were removed or changed. Although in 1987 renewed efforts were underway to expand the boundary of the park on the west side, the dominant concern of park planners was that a new interpretive center and administrative facility be constructed at the park. While visitation had increased, the requirements of wilderness travel made the resources of the park unavailable to many visitors. Media presentations of the less-accessible resources would enhance the understanding and enjoyment of visitors, but the existing temporary facilities could not accommodate any increased levels of interpretation.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

gumo/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 05-May-2001