|

Guadalupe Mountains

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter VIII:

DEVELOPMENT OF THE PARK

Development of the park proceeded by steps, with temporary facilities serving until permanent ones were planned, funded, and constructed. For the first decade of park operation, personnel utilized existing or temporary facilities for employee housing and maintenance activities at Signal Peak and Dog Canyon. They also made do with temporary facilities for visitor contact at Frijole, McKittrick Canyon, and Dog Canyon; with temporary campgrounds; and with the existing trails, boundary fence, and roads to McKittrick Canyon and Dog Canyon until permanent improvements were made.

Residential Area for Park Personnel

From 1962 through 1963, Ranger Peter Sanchez lived at the Ship on the Desert; Roger Reisch also lived there after he took over Sanchez's position in 1964. In 1966, after Congress authorized the park, Noel Kincaid, foreman for J. C. Hunter, Jr., continued to live at the ranch house at Frijole and kept an eye on that area of the yet-to-be established park. However, after the Kincaids moved from Frijole in 1969, Reisch believed he could supervise the entire park better from Frijole than from the isolation of the Ship on the Desert location, so he asked to move to the old ranch house, even though he knew the house was well below the housing standards of the Park Service. In 1972, when John Chapman became the Chief of Operations for Guadalupe Mountains, he and his family moved into the Ship on the Desert. The Ship served as housing for area managers until completion of the permanent residential area in 1982. Reisch lived at Frijole until he became ranger for the Dog Canyon district in 1980. [1]

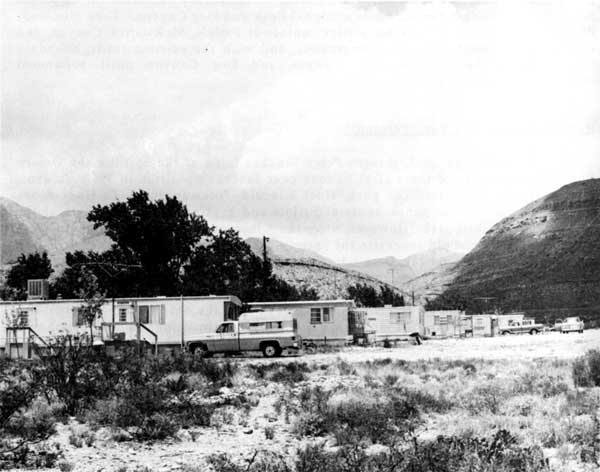

In 1972, in addition to Chapman, several other full-time employees were assigned to the park and needed housing nearby. The site of the Signal Peak Service Station, on one of the non-park sections of land acquired from J. C. Hunter, Jr., had electrical service and water could be piped to the area from Guadalupe Spring. Management selected this site, several miles west of the Pine Springs area, at the foot of Guadalupe Pass, for the temporary housing area. Three double-wide trailers and one single-wide trailer, all used, served as housing. During the next two years, the water and sewage systems at the site were upgraded. In 1976 contractors completed a new well; in 1977 it was connected to the water system, permitting abandonment of the unreliable line to Guadalupe Spring. As the staff of the park grew, management found more used trailers to add to the housing area (see Figure 22). The maintenance shops also were located at Signal Peak. By 1980, the Park Service had made a considerable investment in the site at Signal Peak. Management believed that although the site was outside the park boundaries, the well-developed water system at Signal Peak was a valuable asset which could be of future use to the park. [2]

|

| Figure 22. From 1973 to 1982, park personnel lived in this temporary housing area west of the park, below Signal Peak. As the staff grew, management added more used trailers. The maintenance shops for the park also were located in this area. (NPS Photo) |

The Master Plan approved in 1976 placed the permanent residential area near Pine Springs, south of U.S. Highway 62/180. During the master planning process, environmental groups opposed placing the housing and maintenance facilities on the north side of the highway where natural screening was available but the major resource was closer. They agreed to the location on the south side of the highway in spite of the fact that less natural screening was available there. Planners provided for screening of the residential area by earth berms and vegetation irrigated by sewage grey water. [3]

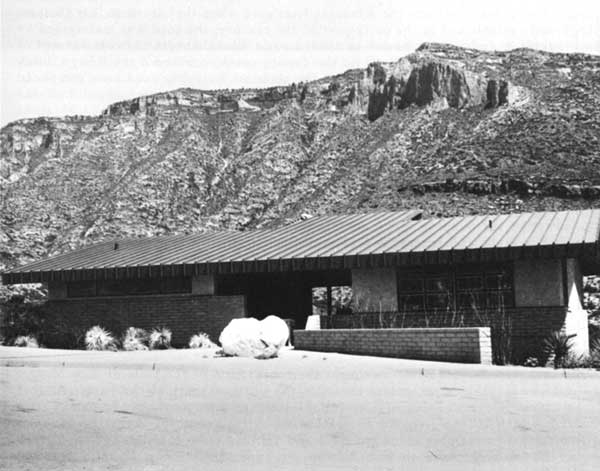

Even before approval of the Master Plan, however, park planners began seeking an adequate water source for all of the development anticipated for the Pine Springs area. In 1973, a well drilled north of the Frijole ranch house, near the mouth of Smith Canyon, failed the pump test. In 1974, Garland Moore, Hydrologist for the Southwest Region, selected a new well site at the mouth of Pine Canyon, near a former Texaco well site. Moore expected drilling to go to 5,000 feet. However, the drillers hit water at 2,673 feet and completed the well in 1976. [4]

After approval of the Master Plan, design work for the residential area progressed rapidly. The architects, a joint venture involving Pacheco and Graham of Albuquerque and Fred Buxton Associates of Houston, met with Park Service representatives in the fall of 1977 to establish design guidelines and concepts. They also met with the residents of the Signal Peak housing area to survey the desires and needs of the people who would live in the new residences. [5]

In December 1979, the initial phase of construction began. McCormick Construction Company, Inc. of El Paso won the contract for construction of roads and utilities in the Pine Springs area; the bid was $1,383,292. The contract included construction of an entrance road, picnic parking area, and restrooms in the campground area north of Highway 62/180, as well as the roads, utility system, water diversion and distribution facilities, and sewage collection and disposal facilities in the residential area south of the highway. Early in 1980, Kent Nicholl of Ramah, New Mexico, bidding $236,000, received the contract for construction of the sewage treatment plant. Nicholl completed the treatment plant in July 1980, but McCormick did not complete the roads and utilities contract until July 1981, considerably behind schedule. [6]

Federal law required all government agencies to negotiate a certain percentage of construction contracts through the U.S. Small Business Administration under the Minority Business Program. In government jargon these were called "8(a) contracts," referring to that section of the legislation that the contracts fulfilled. Under 8(a) contracts, the Small Business Administration was the contractor; a sub-contractor, the minority business, did the work. By early 1980 Superintendent Donald Dayton was frustrated by the 8(a) process. In a briefing document outlining the major issues affecting the park, he addressed the contracting problem: "Excessive delays in negotiating, and unreasonable cost estimates . . ., are causing large losses to the park in what it can expect to obtain from available funds, due to inflationary increases during the long delays. SBA has had letter contracts on three major park projects for 15 months and the projects are still not negotiated." [7]

In October 1980, Park Service officials announced the completion of negotiations with the Small Business Administration for the contract for construction of the housing and maintenance facilities at Pine Springs. The Small Business Administration designated El Paso Builders as the sub-contractor. Included in the contract, which amounted to $1,842,861, were ten three-bedroom and two two-bedroom family units for permanent employees, two two-bedroom apartments, two studio apartments, and three duplex apartments comprising six one-bedroom units. The contract also included a building for maintenance shops and offices. Because construction estimates submitted by the Small Business Administration were much higher than planners anticipated, Park Service negotiators were forced to cut costs for the project. They elected to eliminate the multi-purpose community building planned for the residential area as well as two buildings in the maintenance area, a parking garage for maintenance and ranger vehicles and a storage building for flammable materials. Cost-cutting also forced managers to eliminate the screening measures planned for the residential area. [8]

In February 1981 construction began on the housing and maintenance areas, with completion scheduled for October 1981. In his annual report for that year, William Dunmire, who replaced Dayton as Superintendent in February 1981, noted cryptically that there had been a number of problems associated with the project, problems he hoped would soon be resolved. Jay Bright, a planner from the Denver Service Center who managed the project, spoke less guardedly about some of the problems when he wrote to the Regional Director late in June 1981. He reported that three of the modular residences had been placed and a fourth was on the road. The positions of driveways made maneuvering the truck trailers difficult; Bright predicted continuing damage to road shoulders until all units had been placed. He also noted that the swamp coolers for the installed units had no water supply pipes, but he admitted that the plans had been vague on this matter and suggested that the contractor might justifiably submit a claim for increased costs. [9]

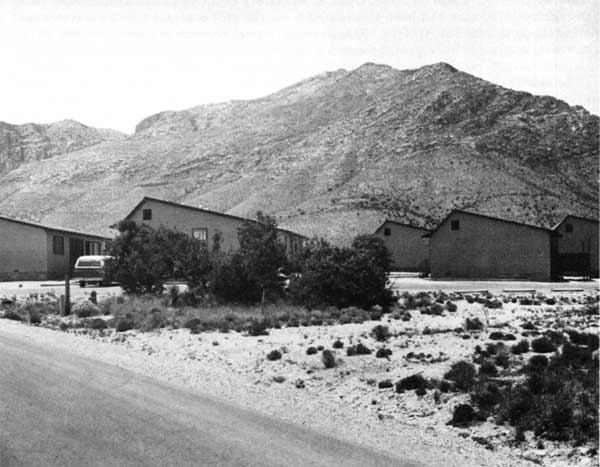

In March 1982 the builders re-roofed all of the new housing because of the inadequacy of the original roofing. This was the last major problem prior to final inspections and approval of both the housing and maintenance areas, which took place early in April 1982. Figure 23 shows part of the residential area, the duplex apartments for seasonal employees. After moving employees to new residences and offices, management sold as surplus all but three of the mobile homes which had been in use at Signal Peak, retaining two 12x60-foot trailers to reuse at Dog Canyon and the third, a double-wide, to serve as the community center for the new residential area. Later in 1982, O&A Contractors of El Paso constructed the paint storage building that had been eliminated from the 8(a) contract for the maintenance area; the cost was $16,997. In 1983, park personnel created a garage for the park's new fire engine from a prefabricated metal building obtained from Salt Flat. [10]

Another type of recycling took place in 1986. In February park personnel planted twenty-eight maple and five madrone trees in the housing area and the campground at Pine Springs. The plants came from a nursery in El Paso and were grown from seeds collected more than ten years earlier from trees in McKittrick Canyon. [11]

McKittrick Canyon

Prior to 1978, the only entrance to McKittrick Canyon was through a private ranch road. The road was closed by a locked gate, and visitors checked out a key through park headquarters at Frijole. Because the owner of the ranch limited the number of vehicles traveling the road each day, park managers instituted an alternative system, transporting visitors to and from the mouth of the canyon by Park Service van on a scheduled basis. The only facilities available to visitors to the canyon were restrooms and picnic tables. After the federal government acquired the right-of-way for a permanent access road, development of the area began. [12]

As at Pine Springs, development in McKittrick Canyon also began with a search for water. In 1976, drillers completed a 71-foot well that pump-tested at 10 gallons per minute, an adequate supply for the planned visitor contact station. Early in 1977, Borsberry Construction of El Paso began the first phase of construction of the new access road to the canyon. During that year the Texas highway department completed the intersection of the park access road and Highway 62/180. In July 1978, Armstrong and Armstrong of Roswell completed the second phase of the road construction. The total cost for road construction was $922,900, with an additional $78,000 for guard rails. To handle the anticipated increase in visitors to McKittrick Canyon, park managers moved a small camping-type trailer to the mouth of the canyon to serve as a contact station (see Figure 24). [13]

|

| Figure 23. View of the duplex apartments, which are part of the permanent residential area built near Pine Springs, south of Highway 62/180. The residential area includes ten three-bedroom and two two-bedroom family units, two two-bedroom apartments, two studio apartments, and three duplex apartments. (NPS Photo) |

In 1979 officials of the Park Service negotiated an 8(a) contract for the construction of the contact station at McKittrick Canyon. The Small Business Administration designated Designs by Oliver of El Paso as the sub-contractor; the amount of the contract was $383,630. Construction began in February 1980 and was scheduled for completion by December 4. In July, already frustrated by delays, the plumbing contractor walked off the job. By the end of the year construction was still incomplete. In his annual report a year later, Dunmire's comments relating to the construction project in McKittrick Canyon were less cryptic than those relating to construction at the residential area. Noting that the scheduled completion date was more than a year past, he reported that the project had been turned over to the bonding company. The most serious problem was the roof, which, because of improper installation, was deteriorating under wind vibration. Inspectors also found rock debris in the water lines, as well as other lesser problems. Six months later negotiations by the Park Service with the bonding company and Designs by Oliver remained deadlocked. Finally, in October the bonding company took over the project and brought in another contractor, who began repairs to the building and roof. The contractor finished in time for the contact station to open on November 6, 1982, the date of the park's 10th anniversary celebration. The new contact station, designed to be operated with or without a staff person, included office and information space, restrooms, a patio area with exhibits, and an automatic audio-visual program with recorded narration by Wallace Pratt (see Figure 25). [14]

Approximately ten days after the opening ceremonies, management closed the McKittrick contact station because of problems with the water system. Consultants from the Denver Service Center came to the park to decide how to repair the system. The water system remained out of operation until May 1983, when it finally was repaired and judged safe for use. [15]

Dog Canyon

From the time of the establishment of the park, road access to Upper Dog Canyon was a problem for park managers and for the rangers assigned to duty at the Dog Canyon station. Although Dog Canyon is only some 15 miles north of Pine Springs, by road the distance from Pine Springs to Dog Canyon is approximately 120 miles. In 1972, persons traveling by vehicle to Dog Canyon followed New Mexico State Road 137 to El Paso Gap, then took Eddy County Road 414 to the Hughes Ranch, about one and one-half miles north of the park boundary. Until 1975, the Hughes permitted vehicles to travel the one and one-half miles to the park on a ranch road, the condition of which often required a four-wheel-drive vehicle to negotiate.In 1975, because increased traffic to the park infringed upon the Hughes's privacy and the safety of their livestock, they closed the ranch road to all but park personnel.

|

| Figure 24. In 1978, after completion of the new access road to McKittrick Canyon, park managers moved a camping trailer to the Canyon to be used as a visitor contact station until a permanent facility was constructed. (NPS Photo) |

|

| Figure 25. The permanent visitor contact station in McKittrick Canyon, completed late in 1982. Numerous problems plagued construction of this facility and delayed its completion by nearly two years. The contact station includes office and information space, restrooms, a patio area with exhibits, and an automatic audio-visual program with recorded narration by Wallace E. Pratt, donor of much of the land in McKittrick Canyon. (NPS Photo) |

Historically, another road, generally parallel to but about half a mile east of the one through the Hughes ranch, provided access to Dog Canyon. This road, across the Magby ranch, was the route the Kincaids first used when they lived at Dog Canyon. Apparently established in the early part of the century, the road was maintained by the county on an irregular basis. In 1964, Laurie Kincaid, with the oral consent of the elderly Lee Magby, who lived on the family ranch, convinced the Eddy County commissioners to improve the county road to the state line. The road crew completed upgrading the road to the Magby ranch house. When they were about half the distance from the house to the state line, one of Magby's sons, who had obtained power of attorney for his father, obstructed any further improvement of the road. The Magbys refused to allow the Kincaids to use the road any longer, so the Kincaids resorted to traveling across the Hughes ranch instead. [16]

While it was necessary to obtain passage of federal legislation to acquire the right-of-way for an access road to McKittrick Canyon, Park Service officials believed the situation surrounding access to Dog Canyon was quite different and could be resolved without the federal government acquiring more land. As early as 1972 officials of the Park Service began negotiating with Eddy County and with the Hughes and Magbys for an access road to the park. Although county officials indicated a willingness to construct a high-standard road to the state line, the estimated cost to acquire the right-of-way, to meet the demands of the ranchers regarding fencing and underpasses, and to construct the road was approximately $100,000, an amount the county officials considered excessive. [17]

In 1973 Park Service officials sought the cooperation of the State of New Mexico to resolve the problem of public access to the northern part of the park. At that time, David King, planning officer for the state, said he would try to obtain state assistance to fence the five and one-half miles of road north of the park boundary. His efforts, however, were unsuccessful and in 1974 state officials indicated they could do nothing more to remedy the situation until Eddy County acquired right-of-way for a road. [18]

Negotiations in 1975 accomplished nothing. Hughes demanded a financial consideration in addition to fencing and underpasses, and Magby increased his price for the right-of-way. At this point Hughes closed the road across his ranch to all but Park Service vehicles. In 1976 Superintendent Dayton sought the help and advice of the field solicitor, Gayle Manges, in reaching a solution to the problem of a road to Dog Canyon. He asked Manges to investigate reopening the Magby road, based on historical evidence that the road was a public road, or, alternatively, reopening the Hughes road, based on the fact that it became a public road after 1964. Soon after receiving Dayton's request, Manges asked the U.S. Attorney General for the District of New Mexico to initiate action to reopen the road through the Magby ranch. No immediate action resulted, but in February 1977 Dayton consulted with Mike McCormick, the district attorney in Carlsbad, and obtained help that ultimately resolved the situation. [19]

For reasons that are not clear, but which may have been related to the adverse publicity generated by the condemnation proceedings undertaken by the government to acquire the Glover property for the park, Eddy County commissioners resisted the idea of bringing suit against the Magbys and Hughes. However, when Tom Rutledge, assistant to McCormick, approached the commissioners and recommended pressing suit to reopen both roads, they agreed to negotiate again with the two families.

As a result of the negotiations, Rutledge and attorney Harvey Fort, who represented Hughes and Magby, achieved a compromise acceptable to county officials, the ranchers, and park officials. Each rancher received $12,000 for a right-of-way three miles long and 60 feet wide, which ran along the fence line separating the two ranches. The county agreed to install sheep fence on both sides of the right-of-way, to install a cattle guard at the beginning of the new road, and to build two underpasses large enough for a horse and rider to pass through. The road would follow the fence line to the southwest corner of the Magby property, then veer southwest to the state line. The agreement included abandonment of the existing road to the Magby house and the construction, by Magby, of a new road to connect with the county-maintained road. The ranchers retained the mineral rights to the right-of-way. [20]

Although the legal problems had been resolved, construction did not begin immediately. Costs for construction of the road were to be shared equally by the state and the county. Since the state eventually would be responsible for maintaining the road, it had to meet their design standards. Problems related to design delayed construction for more than 18 months. At one point, in an effort to eliminate costly elevated crossings at washes, the county went back to the ranchers to seek a different route for the right-of-way. After meeting stout refusals to renegotiate, state highway officials agreed to allow several low-water crossings in the road. By that time, late 1978, park managers wanted to begin drilling a well at Dog Canyon, but no road existed over which a drilling rig could be moved. Dayton devised a creative solution to the problem. He engaged a U.S. Army Reserve engineering unit scheduled for a training session to use their equipment to bulldoze a one-lane route, 10 feet wide, over the county's right-of-way. The county agreed to provide a grader and crew to "finish" the primitive road, which would be used by administrative and contractor vehicles. Eighteen months later, in May 1980, the county completed construction of the permanent access road. Further improvement of the road to Dog Canyon occurred in 1984 and in 1986. In 1987 the state accepted transfer of the Eddy County portion of the road and redesignated the route as part of New Mexico State Road 137. Only four miles of the road, between the western boundary of the Lincoln National Forest and El Paso Gap, New Mexico, remained unpaved. [21]

In 1979, day laborers, using rented equipment, built the road from the park boundary to the ranger station in Dog Canyon. At the same time, park personnel built the permanent campground at Dog Canyon, which was ready for use when the county road opened. The campground, built on the same site as the temporary campground, contained chemical toilets, five parking spaces for recreational vehicles, and 15 walk-in tent sites equipped with tables, charcoal fire grills, and trash receptacles. Until 1982, campers arriving at the park by vehicle had to bring their own water, but the ranger provided water for backpackers hiking into the campground from Pine Springs or McKittrick Canyon. In 1982 contractors built a modern comfort station and brought water lines to the campground. In 1985 the graveled parking area for recreational vehicles was extended 60 feet, and in 1986 park personnel installed a sink and light behind the comfort station for the convenience of campers. [22]

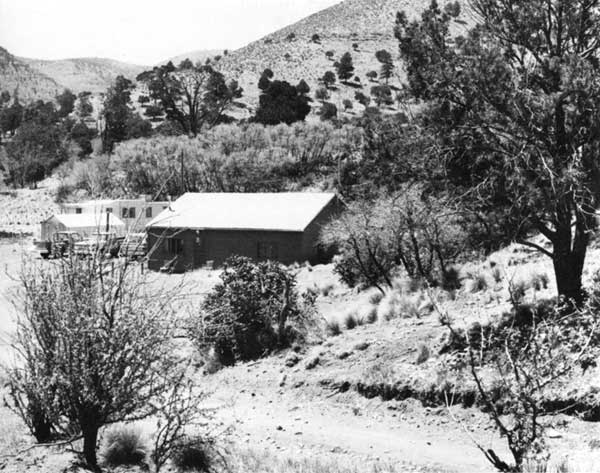

While working to find a resolution to the problem of access to Dog Canyon, park managers also began searching for a water source for a permanent ranger station and residence in Upper Dog Canyon. The rangers who lived in the old Kincaid house (see Figure 26) from 1971 to 1975 hauled water for domestic use from a well 15 miles away. Drilling efforts in 1973, 1974, and 1975 all failed to produce a good well. In 1975 workers cleaned out the spring above the ranch house to provide a temporary on-site water source for the ranger. The next year a mile-long pipeline was laid between the spring and the house and two water storage tanks were installed. In 1977, a chlorinator and cover for the spring were added to the water system. [23]

Management refused, however, to give up the idea of a well. The spring system was less than satisfactory for the development of a residential area meeting Park Service standards provided only emergency water for visitors. In 1978 Congress funded the construction of the new facilities for Dog Canyon, and Garland Moore, the hydrologist who successfully located the well at Pine Springs, took on the job of trying one more time to locate a well site at Dog Canyon. Roger Reisch, remembering Moore's work in the park, recalled that "he got us water everywhere he looked!" In 1979 park managers awarded a contract for $129,546 to Perry Brothers Drilling Company of Flagstaff, Arizona, and Dell City, Texas, to drill the well at Dog Canyon. By the end of 1980, after innumerable problems, creating delays that extended the work over more than a year, and increasing the cost of the project by $30,000, a well, drilled to 3,000 feet, pumped water of acceptable quality at a rate of 12 gallons per minute. Late in 1981 the pumphouse was constructed and plumbing work was completed. A 10,000-gallon reconditioned water storage tank, another salvage item from the former FAA station at Salt Flat, was the reservoir for the new water system. In 1985 park personnel removed the spring box and returned Upper Dog Canyon Spring to its natural state. [24]

|

| Figure 26. An existing ranch house and a trailer moved to the site by the Park Service served as ranger housing at Dog Canyon during the first decade of park operation. (NPS Photo) |

The contract for construction at Dog Canyon was one of three tied up in negotiations with the Small Business Administration during 1979 and 1980. In October 1980 the Small Business Administration designated J. T. Construction Company from El Paso to receive the $334,213 contract. The contract included construction of the ranger station, residence, barn, corral, comfort station, and utilities at Dog Canyon. [25]

The Environmental Assessment for the Dog Canyon Development Concept Plan offered four alternative arrangements for the campground and residential area. Management adopted the alternative in which the ranger's residence and a separate contact station were nearest the entrance to the park, west of the entrance road (see Figures 27 and 28). The barn and corrals for Park Service livestock and the corrals for visitors' horses were farther south on the entrance road, near the trailhead on the west side of the road. Existing stock sheds and corrals were removed and an earthen stock tank was filled and graded to match the natural contour of the land. A ribbon-cutting for the new facilities and a barbecue to celebrate their opening took place in May 1982. [26]

Funding granted in 1978 only allowed for construction of one house. After 1979 a trailer, moved from Signal Peak, served as a patrol bunkhouse and quarters for seasonal workers; in 1983 two additional mobile homes were moved from Signal Peak to Dog Canyon to be used as housing for seasonal rangers and workers. Located near the old ranch house, the mobile homes were out of sight of the campground and trailhead but were still located in a flood plain. In 1983 a new sewage disposal system was added to serve the ranch house and the two mobile homes. One of the mobile homes was later relocated out of the flood plain and near the new ranger residence. Managers disposed of the other mobile home, which was no longer safe for use. In 1987, park managers agreed that besides the visitor center at Pine Springs, an additional residence at Dog Canyon was the only planned residential facility that the park still needed. [27]

|

| Figure 27. The new residence for the Dog Canyon ranger, completed in 1982. Planners located the house near the park entrance, on the west side of the road, a short distance from the campground area. (NPS Photo) |

|

| Figure 28. The visitor contact station at Dog Canyon, completed in 1982. The contact station is near the ranger residence, which is visible at far right in the photograph. The contact station is across the entrance road from the campground. (NPS Photo) |

Backcountry

Trail Construction

The unobtrusive backcountry trails in Guadalupe Mountains National Park belie the amount of money and work-hours expended by the Park Service to plan and build those simple paths. By 1987, the Park Service had spent more than 1.6 million dollars to complete the first three phases of trail construction at Guadalupe Mountains. Phase IV was estimated to cost an additional $500,000.

In mid-1979 Jack Dollan and Robert Steinholtz, park planners from the Denver Service Center, finished construction plans for the first three phases of trail construction and established the priorities for the trail projects.

Phase I: Construction and reconstruction of Pine Canyon, Bear Canyon, and Foothills trails.

Phase II: Construction of Guadalupe Peak, El Capitan, and McKittrick Canyon trails.

Phase III: Construction and reconstruction of Marcus Cabin, Lost Peak, Williams Ranch, McKittrick (interpretive and geology), McKittrick Ridge, and Mescalero Ridge trails; hardening of McKittrick, Mescalero, and Upper Tejas campsites. [28]

Throughout the trail construction program, management faced a continuing problem of finding qualified contractors to perform the work. Because of the limited demand for their services, only a few professional trail-building companies existed. The requirement to utilize 8(a) contractors for the first phase of trail construction compounded the problem. Although the Pine Canyon, Bear Canyon, and Foothills trails were the planners' first priorities, negotiations with the Small Business Administration delayed the beginning of those projects for nearly a year. [29]

While negotiations with the Small Business Administration continued, Dayton worried that the Denver Service Center would pull Dollan and Steinholtz off the Guadalupe project just as construction was scheduled to begin. His letter of August 1979 to the Regional Director emphasized the critical nature of the supervisory role the two planners ultimately played during trail construction. ". . . [I]t is essential that close supervision of these projects be provided for the complete period of time that contractors are on the site. Because of the delicate ecological conditions at Guadalupe, irreparable damage to the resources could be done by the contractors if they do not have daily inspection by experienced trail project supervisors. . . . With the lack of trail experience of the 8(a) contractor, DSC personnel will probably have to act as on-the-job supervisors." Apparently, the Regional Director agreed with the Superintendent's assessment of the situation. In 1987 Dayton recalled the close supervision Dollan and Steinholtz provided and the care that contractors were required to take so they did not damage land and vegetation along the trails. [30]

Although contract negotiations stymied Phase I construction, work began on the second phase of trail construction. Between October 1979 and January 1980, Trio Construction, a professional trail-building organization from Priest River, Idaho, constructed the Guadalupe Peak Trail. The McKittrick Canyon Trail, built by D.D.W. Construction of San Antonio, Texas, was completed in March 1980; in May 1980 Raymond E. Walker, of Alamogordo, New Mexico, completed construction of the El Capitan Trail. The total cost for Phase II projects was $659,000. [31]

From March to June 1980 another professional trail-building company, High Trails, from Wilbur, Washington, constructed the geology and interpretive trails in McKittrick Canyon. High Trails and Trio Construction proved to be the best contractors employed on the trail construction projects. Elmo Warren, owner of High Trails, was a partner with Ralph Larson in Trio Construction before forming his own company. In August 1980, when the sub-contractor designated by the Small Business Administration, ITL Company of Denver, Colorado, finally began work on the trails in Phase I, Warren served as their consultant. Phase I was completed early in November 1980 at a cost of $445,000. While ITL finished Phase I, Warren began work on the contract for the Williams Ranch Trail, completing the project in February 1981. [32]

During the winter of 1981-82, Melvin C. Adams, of Cloudcroft, New Mexico, worked to construct and reconstruct the trails from Dog Canyon to Lost Peak and Marcus Cabin. From June to September 1982, Wilderness Construction Company, from San Manuel, Arizona, built the trails around the Pine Springs and Frijole areas and renovated the visitors' horse corral there. The bid submitted by Wilderness Construction Company began an unusual trend that continued throughout the remainder of Phase III construction. Their bid, $24,999, was about half as much as the highest bid, and much less than half of the engineering estimate of $62,917. In late 1982, the amount of the contract awarded to Trio Construction for the final portion of Phase III was $58,575, again less than half of the highest bid. The bottom had dropped out of the trail-building business and contractors were willing to work for a much smaller margin of profit than only a year earlier. In 1987, Ralph Harris, Area Manager of Guadalupe Mountains, reported that trail-building costs had dropped even lower since 1983, to perhaps as little as one-third of the cost in 1980. [33]

The work completed by Trio Construction in May 1983, included constructing trails on McKittrick Ridge and Mescalero Ridge and hardening three backcountry campgrounds: McKittrick, Mescalero, and Upper Tejas. The actual cost for completion of the work was about $3,000 more than the bid price. Completion of Phase III brought the total of constructed and re-constructed trails to some 52 miles, making the trail density in the park about one mile for every 950 acres. [34]

In 1984 Pete Domenici, senior Senator from New Mexico, unsuccessfully sought funding of the $500,000 needed to complete Phase IV of the trail-building program. By 1986, the trail-building program at Guadalupe Mountains National Park was fiftieth among priorities in the Region, and four hundredth Servicewide. The fourth phase included rehabilitation of 34 backcountry campsites, installation of two pit toilets, and construction of some 28 miles of connecting trails to complete the trail system. [35]

Pine Springs Campground

The Pine Springs campground opened in 1972, when the park was established. It was intended to be a temporary facility, serving only until private enterprise developed a campground near the park. However, the expected privately owned campground did not materialize. In 1974 park personnel installed charcoal cooking grates at the campsites and a vault toilet. The number of campers staying at the campground increased rapidly, from 4,506 in 1972 to nearly 17,000 in 1979. In 1980 the location of the campground was moved a short distance to allow construction of the water reservoir and utility lines for the Pine Springs development, and construction of the permanent restrooms and parking area for the campground. [36]

In July 1981 park managers opened the new facilities at the Pine Springs campground: 19 tent sites and paved parking space for 20 recreational vehicles. The campground had a restroom, but no utility hook-ups. While grills had been removed because of continuing concern about fire danger and environmental concern about the use of native fuels, campers were permitted to use containerized fuel for camp stoves. An error in the design of the sewage disposal system for the campground created problems that were not resolved until 1983. Before the reconstructed sewer and water systems were activated in March 1984, park personnel extended the water lines to four locations in the campground, building pedestals with a spigot and a fountain for the convenience of campers. During 1983 park personnel built a 6x6-foot kiosk for visitor registration and fee collection and constructed new benches for the campfire circle, creating seating for 75 persons. In 1984 camping space was increased to 24 tent sites and two group sites were added, each of which would accommodate 10 to 20 persons. The campground fee of $4 per vehicle per night was first enforced from March to November 1984. Managers later changed the fee collection period to May 15 through September 15 and after April 1987 began collecting fees throughout the year. In 1988 campground fees increased to $5 per vehicle per night or $10 for groups. [37]

Administrative Facilities

While wilderness designation precluded development in the backcountry, two administrative facilities were maintained there: a patrol cabin and an antenna and radio repeater. When the park opened, a log cabin in the Bowl served as patrol headquarters and equipment cache. In 1974 park personnel erected a prefabricated cabin west of the Bowl, permitting abandonment of the log cabin. In 1975, a radio repeater, solar batteries, and antenna were installed on Bush Mountain; in 1981 new equipment upgraded the installation. In 1985, after storm damage, the antenna was replaced. [38]

Fencing

As late as 1987, fifteen years after the establishment of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, park managers regularly dealt with the problems of trespass grazing, illegal trapping of predators and poaching of other wildlife in the park, caused by the non-existence or inadequacy of fencing on the park's perimeter. Until 1982, any fences that protected the park were remnants of the ranching era; some were as much as 50 years old, some were simply drift fences, either outside of or well inside the park boundary, that served the purpose of diverting livestock from the area. According to federal law, landowners were required to prevent livestock from trespassing on park land. In the interest of maintaining good relations with local landowners, managers of Guadalupe Mountains chose to deal with trespass problems unofficially, looking forward to the day when the park would be enclosed by a proper fence, constructed by the Park Service. When rangers found livestock in the park, they herded the animals back across the boundary and notified the owners of the problem. Trespass grazing by exotic wildlife, such as Barbary sheep, was a less-easily controlled problem. [39]

In 1982 the park received its first funding allotment for boundary fencing work. Because a new landowner had recently begun running cattle on several sections adjacent to the west boundary of the park, the most pressing need for fencing was on the west side. In a ten-week program, under the auspices of the Youth Conservation Corps, Area Manager Ralph Harris employed nine youths from the Dell City area. The workers removed old sections of fence, some of which were as much as a half-mile inside the boundary, and put up new sections along the surveyed boundary line. The following year workers from the Youth Conservation Corps took down much of the old fencing in the backcountry and replaced some of the existing fence on the southeast side of the park, near Choza Spring, another area of frequent trespass. [40]

In 1984, based on "environmental and 'political'" concerns, members of the park staff agreed that the next areas to be fenced should be the boundary areas near Guadalupe Springs and Dog Canyon. At Guadalupe Springs, trespass grazing was a frequent problem. Around Dog Canyon, the ill-defined boundary made it easy for hunters in "hot pursuit" of mountain lions to enter park lands. During the spring and summer of 1984 a newly hired fence crew of three men erected one and one-half miles of fence near Guadalupe Springs and two miles of fence along the northern boundary of the park. The projects also served an experimental purpose, allowing management to learn how many miles of fence a three-person crew could construct in rough terrain. During a helicopter training session for the park, fencing materials were sling-loaded and placed at strategic locations along the fence line at Dog Canyon. The total cost of the summer project was $30,000. [41]

Closure of the area around Guadalupe Springs to trespass grazing caused some controversy with the leaseholder on the adjoining land, whose stock had used the water source. The leaseholder, J. C. Estes, appealed to the landowner, Mary Hinson, who in turn contacted her lawyer, Duane Juvrud, and staff persons from the Roswell office of New Mexico Congressman Joe Skeen. After a meeting with all concerned, the Park Service agreed to help Estes haul water for several months until he could sell his livestock at a reasonable price. [42]

In 1985, the Park Service awarded park neighbor Milton (Marion) Hughes a fencing contract in the amount of $24,816. He constructed four miles of fence along the northern boundary of the park, west of Dog Canyon. In 1987, resource managers estimated that only 21 of 69 miles of the boundary had adequate fencing and completion of the boundary fence was the park's first resource priority. [43]

Williams Ranch Access Road

Until 1985, park personnel and visitors traveled the initial three and one-half miles of the 10-mile distance from Highway 62/180 to Williams Ranch over private property. While the access situation was similar to the situation at Dog Canyon, that is, traffic to the park could be obstructed by the landowner, the government owned an unimproved right-of-way nearby on which a road to the park boundary could be constructed. [44] However, given the low level of traffic to Williams Ranch, and the willingness of the private landowner to allow traffic to use an already established ranch road, management did not feel an immediate need to build a road on the legal right-of-way.

Although only high-clearance or four-wheel-drive vehicles could use the ranch road under normal conditions, during the rainy season portions of the road often washed out where it crossed several natural drainages and became impassable for vehicles of any sort. On those occasions, the park manager was forced to close the road to visitor use and to expend money and work-hours to reopen the road. In 1985 park personnel engineered and built a new road within the legal right-of-way. The new road met the old road inside the park boundary, 2.6 miles from Highway 62/180, and shortened the route to Williams Ranch by nearly a mile. [45]

Since the road was intended to be for four-wheel-drive vehicles, the methods used for construction were simple. A road grader scraped vegetation from and levelled a 10-foot wide path, following the centerline established by survey. Between Highway 62/180 and the park boundary the new route crossed only one major drainage. In that area the five-foot high banks were excavated to provide more gradual access to the streambed. The road crossed the wash in an area where natural dams would catch and hold gravel above the road crossing. Two other areas along the route with steeper slopes required cutting and filling to a depth of several feet. The abandoned section of road within the park was blocked with boulders and a gate. Total cost for the new road was less than $5,000. Although washouts continued to occur periodically along portions of the road, they were less frequent than before. [46]

Information and Operational Headquarters

In 1987 the information center and operational headquarters for Guadalupe Mountains National Park still occupied temporary facilities (see Figure 29). In 1976, preliminary planning for the combined visitor center and operational headquarters was complete, and, during that year Congress considered a request for $3,089,000 to complete planning and construction of the facility. In the House Appropriations Subcommittee meeting in 1976, committee members recognized the need for a visitor center and personnel housing at Guadalupe, but they also expressed strong opinions against the tramway concept in the Master Plan for the park. Ultimately, however, circumstances beyond the control of park managers caused the Appropriations Subcommittee members to delete funding for the visitor center for Guadalupe Mountains along with funding for eleven other visitor centers Servicewide. The deletions took place after controversy erupted concerning high cost overruns on the National Visitor Center in Washington, D.C. [47]

|

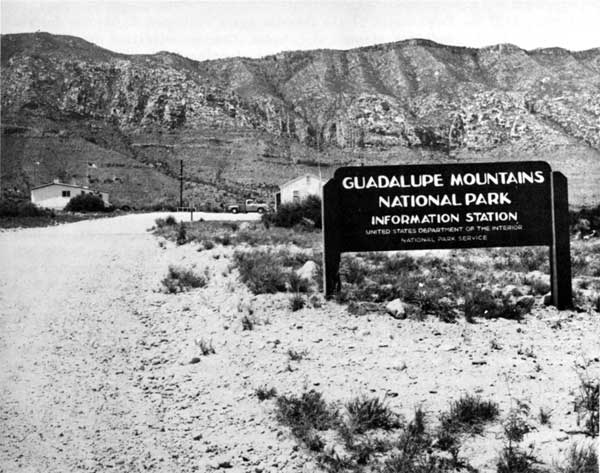

| Figure 29. Temporary facilities. near Frijole: visitor contact station (left) and operational headquarters (right). The visitor contact station, a new double-wide trailer, was installed in July 1979, permitting separation of visitor services and operational headquarters. Previously, the house on right, in combination with a used trailer, had served both functions. In 1983 park personnel added a second small movable house to the operational headquarters, removed the old trailer, and remodeled the newly-created building to better fit administrative needs. (NPS Photo) |

During 1977 the Department of the Interior again requested $3,089,000 for the visitor center at Guadalupe Mountains. Again, Congress deferred funding. A supplemental appropriations bill requesting only planning funds also was deferred. In the latter part of 1977 planners reduced the size of the proposed facility from 9,100 square feet to 8,600 square feet. In 1978 Congress deferred a request for $2,580,000, the revised cost estimate for the building. Subsequently, planners made more changes in the design of the visitor center and reduced the cost estimates by another $700,000. Although in 1979 the Southwest Region listed construction of the visitor center for Guadalupe Mountains as its first priority, the Department of the Interior requested no funds for the construction of the visitor center in its appropriation for 1980. The approved appropriation did, however, include $298,000 for planning and design work for the facility. [48]

The construction design completed by the Denver Service Center in March 1981 contained some surprises. The new estimated cost for construction was $4,658,000, some two million dollars more than preliminary estimates. Even more surprising to the personnel at the park, however, was the design of the building. They thought the high-profile, triangular, sleekly modern building the architects had created was inappropriate for the wilderness character of the park. By June, Jay Bright, Assistant Manager of the planning team at the Denver Service Center, notified the Regional Director that he would hold a "design-in" with staff members from the park, Harpers Ferry Center, and the regional office in order to revise the plans at minimal cost. [49]

In the Park Service, the decision to redesign any facility usually added considerable time to the length of the project and often delayed its completion for years. That was the choice park managers made in 1981 when they rejected the costly triangular design for the visitor center. Between the time of the "design-in" in December 1981 and October 1985, the staff of the park reviewed five designs. In January 1986 the Regional Director approved the design concept that had been accepted by all other reviewers: a building of 7,613 square feet, constructed of stone and wood in a style characteristic of West Texas architecture, with parking for 50 cars, 10 recreational vehicles, and 3 buses. The estimated cost for the building and visitor parking was $2,572,000. [50]

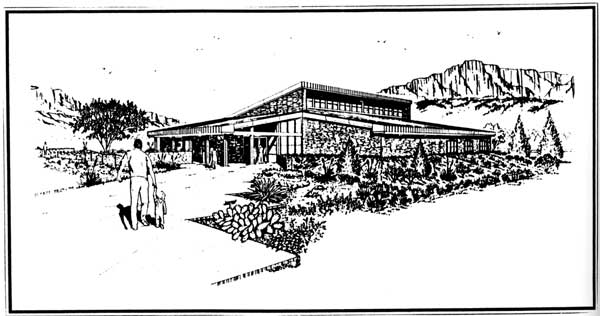

Although by mid-1987 plans for the visitor center and operations headquarters had been revised again, increasing the size of the building by approximately 3,000 square feet, in December 1987 Congress appropriated $3,650,000 for construction of the building. Park managers scheduled the ground breaking for the new facility for May 21, 1988 (see Figure 30). [51]

During an interview in 1987, John Cook, Regional Director of the Southwest Region, reflected on the problems encountered in designing and funding the facility for Guadalupe Mountains. He admitted the design had been a major problem since 1981, but attributed the funding problems to timing, politics, and personalities. Congressman Richard White had been unsuccessful in his attempts to convince the appropriations subcommittee of the park's need for a visitor facility. However, the current Congressman for the district, Ronald Coleman, served on the appropriations subcommittee and apparently had the ear of Chairman Sidney Yates, who had been chairman since the first request for funding for the visitor center. In 1986, working in what Cook called a "forthright way," Coleman succeeded in obtaining the $250,000 needed to complete construction drawings for the visitor center. Early in 1987 Coleman correctly predicted that construction funding would be approved for 1988 if the construction drawings were ready by October 1987. Area Manager Ralph Harris acknowledged the advantages of Coleman's advocacy for the park, but recalled that Coleman did not come into office with a strong personal interest in the park, such as White had. Superintendent Rick Smith and Harris waged an active campaign to cultivate Coleman's interest in the park by keeping him posted on activities and developments taking place there. [52]

While hopes and plans for permanent facilities materialized and disappeared with discouraging regularity during the park's first fifteen years, the staff patiently developed their temporary facilities to maximize efficiency and create an acceptable public image. In 1972, management moved one of the houses from the former FAA station at Salt Flat to a location on the road to the Frijole Spring ranch house, just off Highway 62/180 near Pine Springs. The house served as both information center and operational headquarters for the park until 1978, when a used trailer, installed next to the house, became the office of the area manager. A second trailer, installed near the Frijole ranch house, was the headquarters for the building and utilities foreman until 1982, when maintenance facilities were completed. Although these additions took some of the pressure of administrative personnel off the little house, it still was undesirable as a contact station for a national park. [53]

|

| Figure 30. Artist's rendering of visitor center and operations headquarters which was under construction in 1988, the culmination of more than a decade of planning. (Courtesy of NPS) |

In July 1979, a new double-wide trailer, installed across the road from the headquarters, became the visitor contact station, information center, and reference library for the park. In the new facility, the interpretive staff for the park had room to present an audio-visual program to a small audience and provide a few exhibits for visitors. The new facility also allowed for a sales area for interpretive literature, as well as drinking water, restrooms, and a "rest space," out of the weather. [54]

Once Harris realized that a permanent operational headquarters for the park was years away, he set about making the temporary facility as efficient as possible. In 1983 another movable house from Salt Flat was joined to the existing headquarters building, replacing two trailers. Harris supervised the remodelling of the two buildings, creating offices for the area manager, the chief ranger, and the chief of interpretation and visitor services, as well as space for clerical staff, a workroom, kitchen, and restroom. At the same time, adaptive restoration at the Frijole ranch house made work and office space available there for the district ranger and resource manager. Another house, moved from Salt Flat in 1983, was relocated in the maintenance area to provide much-needed curatorial and storage space for the park's museum collection. [55]

Donald Dayton, William Dunmire, and Ralph Harris shared the headaches of design, contracting, and construction during the period of active development at Guadalupe Mountains National Park, which stretched from 1979 through late 1982. The shifting national economic situation made funding for all park projects more difficult to obtain. Only facilities deemed absolutely necessary or unquestionable, such as housing for employees, utilities, small contact stations, and maintenance facilities were funded. After funding was obtained, prompt construction of the facilities was hindered by the 8(a) contracting process. Most of the construction at Guadalupe Mountains took place at a time when little other construction was going on in the Southwest Region. The bulk of the region's 8(a) contracting obligations fell to Guadalupe Mountains, thereby complicating the normal contracting process. [56] While inexperienced or under qualified contractors contributed to construction delays, other delays resulted from failures or inadequacies in designs. Then, intra-agency disagreements about the design of the visitor center and operations headquarters added at least five years to development of the park's most visible facility. In spite of the delays, however, actual construction of most of the planned facilities took place in a relatively short five-year time period, from 1977 to late 1982. With construction of the visitor center and operations headquarters underway in 1988, the only development projects remaining to be completed were the boundary fence, Phase IV of the trail system, an additional residence at Dog Canyon, a community center for the Pine Springs residential area, and a garage for the maintenance area.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

gumo/adhi/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 05-May-2001