|

Homestead National Historical Park Nebraska |

|

NPS photo | |

An Invitation to the World

For over a century the Homestead Act fed people's desire for land and a home of their own. It materialized an American dream.

Today's immigrants from Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Central and South America, and elsewhere share a dream with the homesteaders who came to America's interior in the post-Civil War era. Like today, it was a roiling, uncertain time of rapid social and economic change—migrants leaving northeastern factories; formerly enslaved people leaving Southern plantations; sharecroppers leaving worn-out fields. Many headed west. All acted on the promise of a dream: mobility and property for people who had none, or who wanted more.

Homesteaders Took Risks, Found America

Twenty-five thousand Europeans, most of them German, crossed the Atlantic in the first half of 1862. The precise number of immigrants who followed with the intention to homestead, or how many first lived and worked in the cities before they caught "land fever," is unknown.

By 1870 one-fourth the population of Nebraska was foreign-born. By the turn of the century over two million Anglo-Americans, Swedes, Italians, Danes, Finlanders, Hollanders, Icelanders, Hungarians, Russians, Bohemians, Poles, and Ukrainians had relocated to the Great Plains—homesteading's heart. "Free land," but also civil freedom, the perception of unlimited resources, independence, and a chance for free education drove the "briskness in immigration."

Territories and states coined names like "The Treasure State" (for Montana, which had rich mineral deposits), enhancing their appeal. The Exoduster movement, led by Benjamin Singleton, a carpenter and undertaker from Tennessee, promoted a near-Utopian vision of homesteading as a way for former slaves to get land and homes in Kansas. Many African Americans, including women, managed to file and "prove up" (fulfill legal requirements) on claims.

Homesteading states mounted booster campaigns to entice emigrants. Women from age 21, including those who had been deserted, could take "free" land. Many did. While homesteading, some worked as domestics to earn cash. Karolina Miller Krause, an Austrian immigrant, did field work—usually considered men's work—to help buy a farm.

Foreign-language advertisements and reports printed in the US and distributed in Eastern Europe, where crop failures led to famine in the 1870s, promoted the idea of an American land of plenty. One Polish-language article published in 187S described a rail tour through bountiful farmlands. The Bissie family, from Poland, found work on American farms.

Despite immigrants' practical skills and willingness to work, not everyone welcomed them. Today's Twitter feeds could be responding to an opinion the New York Times published in 1907: "The opposition to the present immigrant is uneconomic, illogical, and un-American."

1915 was a "miracle" year for homesteaders. Abundant rain, bumper wheat harvests, and high grain prices (owed to the Great War in Europe) caused Great Plains economies to boom. Government posters declared "Food Will Win the War!" But as the war ended, corn and wheat prices dropped. Economic depression settled in, as did severe drought. Many homesteaders abandoned suddenly unprofitable claims. Yet even in the 1930s—America's bitterest decade—homesteaders moved westward. Undeterred, or made desperate by the Great Depression, they filed new claims.

Cycles of boom and bust, soaring hope and deep despair, would temper but not wholly destroy homesteading's promise. Many failed to "prove up" their claims. Many more—across 30 states, from diverse national, cultural, and economic strata—faced drought, prairie fires, hailstorms, tornadoes, grasshopper plagues, and often crushing loneliness. They persevered.

In 1976, the US Congress repealed the Homestead Act. Over 123 years, homesteading gave hope to many. It offered immigrants a road map that took them from serfdom to citizen- and property-ownership. It offered the nation's own disenfranchised—the formerly enslaved, veterans of civil and world wars, emigrants from northeastern factory towns, and southern sharecroppers—men and women alike—a chance.

Wild Lands to Farmlands

Public Domain Lands Spur Debate

1785 Public Land Survey System (PLSS), first proposed by Thomas Jefferson, is established to divide public domain lands

1800 Land Act reduces the size of a unit of public land from 640 acres (one square mile) to 320 acres (half-parcel)

1803 Louisiana Purchase from France adds 800,000 square miles, doubling the public domain

1830 Indian Removal Act adds 40,000 square miles to public domain lands east of the Mississippi

1846 Oregon Treaty with Britain sets northern border of US; adds 28,000 square miles to public domain

1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo with Mexico adds 528,000 square miles to public domain (Texas excluded)

1848-52 Free Soilers support free homesteading and oppose slavery in new territories

1849 California gold rush

1850s The fight in the House and Senate over public lands builds to a crescendo. Many decisions turn on whether slavery will be extended to the western territories

1853 Gadsden Purchase of parts of Arizona and New Mexico from Mexico adds 123,000 square miles to public domain

1860 Abraham Lincoln elected President

1861 Civil War begins

1862 Homestead Act offers 160 acres of public land free to homesteaders; Pacific Railway and Morrill Land-Grant College acts

1863 Daniel Freeman and other homesteaders begin to file claims, mostly in the Great Plains states and Nebraska and Dakota territories

Populating the Land

1865 Civil War ends; Reconstruction in South begins

1866 Congress extends homesteading to the five public land states in the South—Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas

1877 Following Reconstruction's failure and Southern states' enactment of the notorious Black Codes and Pig Laws, African Americans migrate North and West. Many seek free lands and greater tolerance in Kansas, a Union stronghold during the Civil War. They become known as "Exodusters"

1889 Oklahoma Territory opens to homesteaders with a "land run." Thousands join the frenzied sprint to stake claims

ca. 1901 First 4-H club

1902 Land Reclamation Act, to provide water to arid and semiarid West and Southwest

Peaks and Valleys

1901-20 Homesteading peaks; Land Office issues over 800,000 patents

1913 Willa Cather publishes Prairie Trilogy

1914-18 World War I

1929 Stock Market crashes

1930-40 Land Office issues 40,000 homestead patents, many in the Southwest

1934-36 Dust Bowl

1936 Homestead National Monument of America established; Rural Electrification Act

Resurgence and Repeal

1939-45 World War II

1946 Department of Agriculture establishes Farmers Home Administration

1948 Center-pivot irrigation delivers water to crop fields

ca. 1950 Manufacture of most horse-drawn farm equipment ceases

1956 Congress passes Interstate Highway Act, allowing faster transport of farm goods to market

1960-86 Public lands in Alaska opened to homesteaders

1976 Congress repeals Homestead Act in lower 48 states

1986 Congress repeals Homestead Act in Alaska

1988 Last homestead patent issued

Tallgrass Prairie Reborn

Between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains are remnants of the grassy expanse once called the Great American Desert. Foot-high buffalo grass and blue grama grasses covered the dry area east of the Rockies. Needle-and-thread grass and little bluestem dominated the middle belt.

The easternmost lands of the lower Missouri valley, where rainfall is higher, are home to the tallgrass prairie. Its big bluestem, little bluestem, Indiangrass, and switchgrass rise 8 or 9 feet tall, with roots that reach 15 to 25 feet down into the soil. Plants native to the tallgrass prairie are tough. They survive grazing, fire, and mowing.

By the 1930s successive droughts and overgrazing had destroyed much of the tallgrass prairie in eastern Nebraska. Plants native to the more arid prairies (western wheatgrass, blue grama, and buffalo grass) invaded.

In 1939 the National Park Service began restoring the tallgrass prairie here by planting grass seed from a nearby farm. Restoration continues today with methods like controlled burning. Burning in spring, before non-native grasses begin to grow, incinerates dead plant debris. This allows sun and rain to penetrate and releases nutrients that promote growth and seed yields.

Not just tall grasses but also other plants and flowers (330 species) thrive here. The tallgrass prairie ecosystem includes trees, birds, mammals (60 species), insects, and microorganisms. Songbirds like the dickcissel and meadowlark often sway precariously atop grasses and shrubs. They winter in South America and Mexico, then migrate to North American tallgrass prairies to nest and raise their young.

Explore Homestead

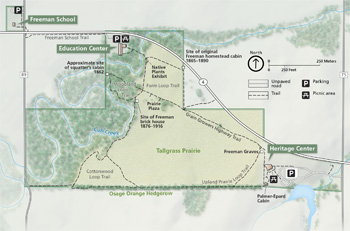

(click for larger map) |

Homestead National Monument preserves the T-shaped, 160-acre claim that Daniel Freeman filed on January 1, 1863. It includes the school that some of Freeman's children attended, a typical eastern Nebraska cabin, and 100 acres of restored tallgrass prairie.

The park is open daily except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. Hours vary seasonally; check our website.

Start at the Heritage Center, which offers information, exhibits, a bookstore, and a film. Visit the Palmer-Epard Cabin, see pioneer farm implements in the Education Center, and walk the trails through tallgrass prairie. Enjoy the Heritage and Education centers' picnic areas Check our website for special events and ranger-led talks. Call ahead for group tours.

FOR YOUR SAFETY

• Stay on trails. • Watch for poison ivy and nettles. • Check for

ticks. • Beware of steep dropoffs near Cub Creek. • Fires and smoking

are prohibited. • Pets must be leashed, and are not allowed in buildings or

on trails. • Bicycles and vehicles are prohibited on trails. • For

firearms regulations check the website.

Federal law prohibits removing natural or historic features.

Emergencies call 911

Accessibility

We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all; call

or check our website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2016)

Documents

A Herpetofaunal Inventory of Homestead National Monument of America NPS Technical Report NPS/HTLN/HOME/CA6000A0100 (Daniel D. Fogell, March 2004)

America's Invitation to the World: Was the Homestead Act the First Accommodating Immigration Legislation in the United States? (Blake Bell, Date Unknown)

An Archeological Survey of the Homestead National Monument of America (Christopher M. Schoen and Peter A. Bleed, February 1, 1986)

Analyzing Water Isotopes in Mesic Bur Oak Forest, Homestead National Monument, Nebraska (Rodney A. Chimner and Sigrid C. Resh, March 3, 2010)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America: 1996-2011 Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2012/612 (David E. Bowles and Myranda K. Clark, August 2012)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska: 2005-2007 Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2009/242 (David E. Bowles, September 2009)

Bat Acoustic Monitoring September 2016: Homestead National Monument of America NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HOME/NRR—2017/1401 (Daniel S. Licht, March 2017)

Bird Community Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska: 2009 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2010/046 (David G. Peitz, April 2010)

Bird Community Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska: Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2014/853 (David G. Peitz, March 2014)

Breaking New Ground: Administrative History of Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska (Bruce G. Harvey and Deborah Harvey, 2020)

Cultural Landscape Report: Homestead National Monument of America (June 2000)

Deer Census at Homestead National Monument of America Using Drive Method (Jesse Bolli, March 2004)

Excavations at the Freeman School (25GA90), Homestead National Monument of America (Christopher M. Schoen, May 15, 1986)

Fish Community Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America: 2004-2011 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2012/276 (Hope Dodd and J. Tyler Cribbs, April 2012)

Forest Inventory of Vascular Plants at Homestead National Monument of America and Annual Community Monitoring Results, 2002 (Karola E. Mlekush and Michael D. DeBacker, January 17, 2003)

Foundation Document, Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska (August 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska (January 2015)

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) Early Detection Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2010/259 (Mary F. Short, Craig C. Young, Chad S. Gross and Jesse M. Bolli, October 2010)

General Management Plan, Homestead National Monument of America Final (1999)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Homestead National Monument of America NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2011/452 (J. Graham, September 2011)

Historic Structures Report/Historical Data Section: The Palmer-Epard Cabin (Part II), Homestead National Monument of America, Beatrice, Nebraska (Lenard E. Brown, June 1968)

Homestead National Monument: Its Establishment and Administration (HTML edition) (Ray H. Mattison, reprinted from Nebraska History, Vol. 43 No. 1, March 1962; ©History Nebraska)

Homestead National Monument of America (H.C. Luckey, extract from Nebraska History Magazine, Vol. 16 No. 1, January-March 1935; ©History Nebraska)

Homestead National Monument of America: An Administrative History, 1962-1981 (Robert Tecklenberg, 1982)

How the West Was Settled (Greg Bradsher, extract from Prologue, Vol. 44 No. 4, Winter 2012)

Into the 21st century Homestead National Monument of America prairie management action plan 1993-2000 (John F. Batzer and Rebecca Dahle Lacome, March 1993)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America: Year 1 (2006) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2007/020 (Craig C. Young, J. Tyler Cribbs, Jennifer L. Haack and Holly J. Etheridge, March 2007)

Inventory of Distribution, Composition, and Relative Abundance of Mammals, including Bats (at) Homestead National Monument of America NPS Technical Report NPS/HTLN/HOME/J6370040013 (Lynn Robbins, July 2005)

Junior Ranger Program, Homestead National Monument of America (2008; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Program, Homestead National Historical Park (2021)

The Not-So Junior Ranger Program, Homestead National Historical Park (2021)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Freeman Homestead and Freeman School (David Arbogast, Thomas Busch and Richard Ortega, December 19, 1975)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Homestead National Monument of America NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HOME/NRR-2019/2049 (David S. Jones, Roy Cook, John Sovell, Christopher Herron, Jay Benner, Karin Decker, Andrew Beavers, Johannes Beebee and David Weinzimmer, December 2019)

Newsletter (News from the Homestead)

2022: January

2021: January • February • March • April • May • June • August • October • November

2020: January • February • March • April • May • June • July • August • September • October • November • December

2019: March • April • May • June • Homestead Days Special Edition • July • August • September • October • November • December

Overview of Digital Geologic Data for Homestead National Monument of America (September 2011)

Plant Community Monitoring Trend Report, Homestead National Monument of America NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2007/028 (Kevin James and Mike DeBacker, May 2007)

"Planted in the Soil": The Homestead Act, Women, Homesteaders, and the Nineteenth Amendment (Jonathan Fairchild, 2023)

Prescribed Fire Monitoring Report, Homestead National Monument of America, 2014 (NFPORS ID3325472) NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HOME/NRDS—2015/745 (Sherry A. Leis, January 2015)

Prescribed Fire Monitoring Report, Homestead National Monument of America, 2015 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2016/1004 (Sherry A. Leis and Cody Wienk, January 2016)

Resource Briefs

2010 Breeding Bird Survey Results for Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska (David G. Peitz, Kevin M. James and Chad S. Gross, undated)

2015 Monitoring Summary for Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska (David G. Peitz and Chad S. Gross, undated)

2016 Monitoring Summary for Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska (David G. Peitz, undated)

Aquatic Community Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America (2009)

Aquatic Invertebrate Community Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America (2012)

Fish Communities at Homestead National Monument of America (2012)

Fish Community Monitoring in Prairie Park Streams (2005)

Homestead National Monument: How might future warming alter visitation? (June 21, 2015)

Monitoring Problematic Plants in Homestead National Monument of America - 2013 (Craig C. Young and Jordan C. Bell, 2013)

Plant Community Trends at Homestead National Monument of America (2007)

Plant Community Trends at Homestead National Monument of America (2011)

Recent Climate Change Exposure of Homestead National Monument of America (July 31, 2014)

Results of the 2014 Birding Efforts at Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska (Robin D. Graham, undated)

Results of the 2015 Woody Thicket Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska (Jennifer L. Haack-Gaynor, undated)

Restoration of the Tall Grass Prairie at Homestead National Monument, Beatrice, Nebraska (David E. Hutchinson, extract from Rangelands, Vol. 14 No. 3, June 1992)

Soil Survey of Homestead National Monument of America, Nebraska (2013)

Thicket Monitoring at Homestead National Monument of America 2000-2010 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2012/270(Jennifer L. Haack, March 2012)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Homestead National Monument of America: Project Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR—2011/345 (Kelly Kindscher, Hayley Kilroy, Jennifer Delisle, Quinn Long, Hillary Loring, Kevin Dobbs and Jim Drake, April 2011)

Vegetation Mapping Project, Homestead National Monument (2011)

Unsung Treasures of the National Park System: The Homestead National Monument (Part One)

home/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025