|

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

Administrative History |

|

|

Administrative History Bob Moore |

CHAPTER ONE:

The Gateway Arch Parking Garage

One element of the Memorial's development which remained uncompleted at the outset of the 1980s was the construction of a parking garage, to be used by both tourists and the downtown business community. As early as 1958, the creator of the Arch, Eero Saarinen, conducted a feasibility study for a parking facility as part of his plan for the overall development of the Memorial site. Despite favorable conclusions, a lack of funds prevented any work. [1]

The City of St. Louis and the National Park Service signed a cooperative agreement in March 1956 to construct an open-air parking lot on the north end of the Memorial grounds. The agreement provided for a section of land to be set aside in the northwest corner of the Gateway Arch grounds for the garage, which would be large enough for 1,020 vehicles. The completed facility was to be considered the joint contribution of the United States of America and the City of St. Louis to the completed memorial. [2] Despite delays of more than twenty years, the desire for a parking garage, especially on the part of the city, remained strong. In 1978, another feasibility study was approved by the Park Service, but funding continued to be a problem. [3] It was with the arrival of Superintendent Jerry Schober in 1979 that the project was put into motion again. Schober recalled:

I began to see agreements that were made by [former JEFF superintendent] George Hartzog. Now these agreements in the past had just sat there and let dust pile up on them. There was one made in 1956 between the City of St. Louis and the Park Service which was finally modified in '62. [4] We had a dinky little hole in the ground on the north end of the park which was supposed to hold up to 320 cars and they were going to have the city operate it. Totally inadequate. Particularly when you realize that the whole length and breadth of this area that the Arch is on now was a big parking lot for the city. And when we began to develop the memorial we took that many spaces from them with the promise that we were going to bring them more and more visitors. So as the visitation jumped up to around 2.5 - 2.7 [million] we were taking up all the parking everywhere, [especially] from those people who had to work downtown.

We made another agreement which enabled the Bi-State Development Agency to design . . . and construct the tram system that went to the top of the Arch. Bi-State became our partners. The agreement which allowed the design and construction of the trams had a clause that it would last until 1992 or until the bonds were paid off. Interestingly, the bonds were paid off in 1982. Many people thought in reading the agreement that this terminated our partnership. However, there was a clause in the agreement which stated whichever occurrence came last, either the 30 years (1992) or the paying off of the bonds (1982). [5]

In 1980, the city informed the National Park Service that it intended to build a parking garage on the site of the existing lot, at a cost of approximately $12 million. The money was to be raised by selling revenue bonds, but the plan fell through because the bonds were tax exempt and so carried no federal guarantee. [6] Superintendent Schober remembered the initial phase of the development of the parking garage project:

The agreement between the city of St. Louis and the National Park Service . . . said that we would allow the city to come in and develop a facility for parking cars which would take care of their needs and ours. But it would be built at their expense. The city certainly didn't have any money, they felt, to come in and develop [a garage] for the National Park Service. But when I got here I worked with the mayor who was in office at that time, Jim Conway, who . . . consented to consider building a facility at the north end of the park. I mentioned to him that I would give them a permit which allowed them to construct the facility, and as soon as it was completed it would become the Park Service's, or as soon as it was paid off.

Well, Mr. Conway, election time, was defeated, and Mayor Vince Schoemehl was elected. So I went over and I talked with him about the possibility of carrying out the approach that Mayor Conway and I had agreed upon. He went along with it too. This started something that was much too long in negotiations. We would meet about every month and we would talk about how we were going to raise the money. The City of St. Louis' bonding rating was very poor, about double B or something like that. . .

At every one of these meetings I brought with me an agent of Bi-State, who we felt should be the ones to go ahead and build [the garage], but our agreement said that the City would build it. I think we probably met over a period [of] about eighteen months. . . . What I was trying to get across to the city was we wouldn't tell them where they could find the money that they were to build with. We were not even going to ask them where they got it. We just wanted them to carry out their commitment. And so in trying to get this point across, one day I said to the city officials: "My old grandpappy said: If you're going to do your own barking you don't need a dog." . . . This is a strange thing, but that little homespun philosophy for some reason cleared the air.

I said: "Let me get my point across. You say, you don't have the money to construct. I am not asking you where you get the money. I've been bringing a gentleman to these meetings every time we've met [the Director of Development for Bi-State, John Booth], and Bi-State is willing to float the bonds and give you the money, and you can build the garage thereby fulfilling our agreement." And they said: "Oh, okay! We'll change the Park Service's [agreement]." And I said, "No, you leave our agreement alone. The City makes an agreement with Bi-State. You fund it, we build it, and we become then a three way partnership." Well, you'd be shocked.

From that point on we began to work. And it was a very short period before we had sold the bonds. [7]

|

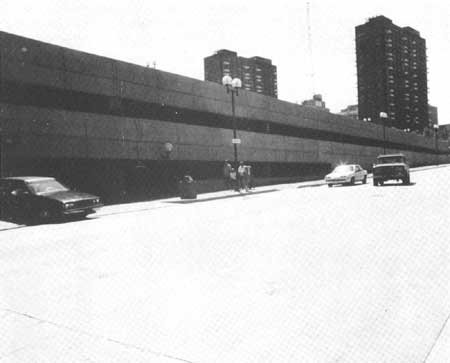

| The parking lot on the grounds of the Gateway Arch, May 1978. NPS photo. |

By 1983, the National Park Service and Bi-State Development Agency amended their formal agreement for the operation of the Arch trams to expedite the financing and construction of the Gateway Arch parking garage. The agreement with the city for the operation of a 1,208-car parking facility on the 4.7-acre site was not changed; the land was federally owned and subject to NPS control. Under a lease/construction/management/operating agreement, the city supervised construction, with Bi-State Development Agency the project director. Funding for construction was provided by Bi-State with the sale of $8,400,000 of Gateway Arch Parking Garage Revenue Bonds, Series 1983. [8] The bonds were to be repaid from garage revenue; however, more than $1.2 million of Arch tram funds were to be held in a separate account to assure the bonds. No taxpayer funds were involved in this innovative approach to providing badly needed parking for visitors to the Gateway Arch. [9]

The garage was planned as a three-story structure, with two levels below ground and the top deck built on a contour with the Arch grounds. Superintendent Schober told the press that the area would be more attractive once the garage was built, "Because most of the cars will be hidden from view." It was planned that the top deck of the garage could be used for special events as well. Fred Weber, Inc. of St. Louis came in as the low bidder, and was awarded the contract for $6,262,000 to build the garage. [10]

In March 1983, an environmental impact statement was approved by the State Department of Historic Preservation. The impact study was required since both the Eads Bridge and the Gateway Arch were on the National Register of Historic Places. Since the construction was to be implemented in an area of potentially significant archeological discoveries, the project was monitored. At first, neither the city, the park, nor Bi-State thought such monitoring would be necessary, since the entire project was to be constructed on disturbed earth and landfill brought in during the construction of the Arch and creation of its landscape design in the 1960s and 70s. When the Missouri state historic preservation officer raised the issue, recalled Jennifer Nixon, [11] "Bi-State telephoned several local institutions for bids on archeological monitoring. Southern Illinois University called first." [12] On February 2, 1984, at a meeting between representatives of Bi-State, the National Park Service, the City of St. Louis, and Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville (SIUE), an agreement was made with William I. Woods, staff archeologist at SIUE, to supervise on-site archeological monitoring. Artifacts recovered were retained by the park, and the circumstances of their discovery and location were recorded. [13] The selection of Woods caused some bureaucratic controversy, despite his excellent credentials and the fact that he had worked on "historic sites of comparable age to the riverfront in St. Louis . . . [as well as] a variety of 19th century sites." [14] The controversy involved the use of an archeologist not retained by the National Park Service's Midwest Archeological Center.

Monitoring began on February 3, 1984. The upper portions of fill dirt brought in during the construction of the Arch had already been excavated by that time, but it was felt that "the 6 feet of rubble that had been removed probably reflected the 3 feet that remained." [15] As Superintendent Schober remembered:

We didn't find anything. . . . We dug down to quite a big depth and ended up finding streets underneath it with stone walls. That much earth had been brought in as fill around the Arch. Even when we [excavated for] the irrigation system in 1980-81 we were uncovering tombstones and all that were not from the cemetery out here but that had been hauled in as fill and dumped. Many of the old warehouses that were where the garage sits probably had two sub-basements in them, and when they razed them they must have just pushed one floor into another and just dropped them. We really did not find any kind of major artifact whatsoever. In fact, probably if we had, you would have wondered if it was dug from somewhere else and brought out here as fill. [16]

A professional archaeologist monitored the excavation intermittently on-site between February 3, 1984 and January 4, 1985. "During that time, SIUE personnel defined, mapped, and photographed three stratigraphic profiles and six cultural features or portions of features. None of these features is considered to represent an intact cultural resource dating before 1849." The archeological report stated that "the site appears to have only occasional foundation remnants that have no dates or related material. The only material has been recovered from the rubble which consists of some burned debris and building materials. . . . This fill probably dates from the time the area was leveled for Arch construction. Materials associated with the rubble consist of building debris (bricks, limestone, granite blocks, and some wood and iron). In addition, the rubble contains glass and china dating from the early 1900's. The fill presumably extends to bedrock (434.0 ft - 420.0 ft) in this area." [17] Although the area was found to have been untouched by the 1849 fire, the conclusion of the archaeologists was that post-1849 urban renewal had completely destroyed any earlier structures, and the foundations and artifacts recovered were of little historical value. [18]

There were several problems with the construction. First, all the fill put in during several phases of construction and landscaping on the Arch project had to be removed, down to the limestone bedrock in some places. "We found all sorts of garbage in the fill, including large metal objects such as old boilers," recalled Jennifer Nixon, who served as the project supervisor for Bi-State.

The design for the garage used piers rather than pilings in the structure, which turned out to be a costly decision. A piling is a huge steel I-beam driven into the ground, on which the concrete could rest. Instead, Bi-State accepted concrete piers, which were poured in place, into constructed molds called casings. The area for the casings had to be drilled out of the fractured limestone bedrock, not an easy task. Fractured limestone has dolomite in it. We needed to use an industrial-strength diamond bit. As we drilled, we were hitting lots of stuff in the fill and struggling to get through the dolomite. Then the water had to be pumped out; we hit natural springs in two places. The casings needed to have a footing, so they had to flange outward at the bottom. What a job! When going into this type of limestone, it would have been much better and faster to use pilings. The construction was slowed to the extent that the project had to be re-financed on April 1, 1986. [19]

As the parking garage neared completion, Bi-State and the Park Service made arrangements for its operation. It was agreed that Bi-State would operate the facility and that the NPS would provide protection and maintenance on a reimbursable basis. [20] This was problematical with NPS officials in Washington, who maintained that the park would, in effect, be charging a fee for providing a service, which was not acceptable according to NPS policies. [21] "This was something entirely new," recalled Jerry Schober.

We felt like it's called the "Arch Garage." Everybody who comes there really thinks it's part of this facility, the Arch, and they think they're protected by rangers. So when I found out what Bi-State was going to have to pay for bringing private guns in, to get security from an outside group, I tried to say to Ms. [Jennifer] Nixon, for roughly $99,000 we'll give you twenty-four hour protection and we'll have a uniformed ranger on-site. [22] Well, what I found out from the Park Service was that you can't accept money that way. They would have to give that money to general receipts. So, the first thing I decided to do, I asked if they would donate that money. This is unheard of by a quasi-political group such as Bi-State. They are, by the way, legislatively charged to operate in Illinois and Missouri — anything in transportation. And [Midwest Regional Director Charles H. Odegaard] said "If it's donated, yeah, I guess you can go ahead and your people can operate it." So, [Bi-State] said they'd donate it. . . . All of a sudden the Washington Office got that information. . . . We had already hired the rangers, we had them in operation. And [Washington] came back and said "That [money] wasn't donated. That would [be] just like you requesting that money to be funded. And because of it we are not going to spend one nickel of it, we are going to return it to Bi-State." Meanwhile I've already hired rangers and everything is hot to trot. [23]

The situation remained unresolved even after the official opening and dedication of the garage on May 8, 1986. In the meantime, the park provided the services despite having no funding for them. Schober continued:

So, I felt like it was time for me to go to my congressman and my senator. When I was in California, I asked one of the most powerful representatives in the House, a guy named Phil Burton . . . why he wouldn't pass a bill that said all the funds that the Park Service generates stay within the parks, whatever park generated them. He said no, because Congress wants all the funds sent to them and they would allocate the money where they felt park needs required it. . . . So I asked that of Dick Gephardt when I came here. And he too smiled, and said no, for the same reasons as Burton. So then I thought, let's try — no park had tried this one . . . what about [our park, specifically: Jefferson National Expansion Memorial? Then I] . . . went to my Republican senator, Jack Danforth, and talked to him also. [24]

With the assistance of Senator John C. Danforth and Representative Richard Gephardt, the park was able to achieve passage of Public Law 99-591 in 1986, which granted reimbursable authority to JEFF. This meant that non-Federal funds generated within Jefferson National Expansion Memorial would stay in the park, and be used at the discretion of the superintendent. JEFF was the only park in the National Park System with such a provision in its legislation. [25] Subsequently, an agreement was negotiated with Bi-State Development Agency, whereby the costs of providing resource and visitor protection and certain maintenance activities for the Arch parking garage were paid out of funds generated at the garage, at no cost to the Service. [26] Superintendent Schober continued:

I was a little chagrined because I couldn't get anyone from the National Park Service to come and cut the ribbon at the dedication. I interpreted this as [meaning] this was so different and so unusual, they were not going to be a party to be around in case it didn't work. [27]

Finally, P. Daniel Smith, deputy assistant secretary of the interior, consented to speak for the Park Service at the opening on May 8, 1986. In a unique ribbon cutting ceremony, Norbert Groppe, president of the St. Louis Board of Public Service, and Carl Mathias, chairman of the Bi-State Development Agency, held opposite ends of a large ribbon which motorists were invited to break through with their cars, thus entering the new garage. [28] The postscript to the garage story was perhaps the most exciting facet of the entire project. Jerry Schober explained:

. . . Now, some of the creative, we might call it, management that took place, included the fact that people weren't ready to buy these bonds if they did not feel they had some security, since the structure was being built on government property. It's not like the bondholders could take it over and could take the business somewhere else. And so something had to sweeten the pot. And what I ended up doing was, from this money that Bi-State had been putting in a fund for the National Park Service, we said that we would secure the parking facility with the operation of the [Arch] tram. And I pledged, if my memory serves right, $1,274,000 to keep it at that level, in a sinking fund.

This fund was there for nothing but an emergency. . . . We've come very close but we've never been in the red. So, somewhere down the line, when all the bonds have been paid off, whoever is manager of this park is going to find it was like winning the Lotto. There will be $1,274,000 sitting in a fund. It's been nothing but the protection to the bond holder and a guarantee from the Park Service. But what we have here [with this parking garage] is an 8.5 million dollar gift from the outside, and no one feels like they have been a loser.

So, this park, maybe for the first time, tried to show that there are many ways that you can manage, and that you can manage within the structure of the Federal Government. Just because it's different doesn't mean it's illegal. And so, after a while, we did so many different things here, when Director Bill Mott was in, I tried to get him to designate this as a demonstration park for no other reason than if you have some unique things you want to try out, and since we are near enough to a city to get support, since we have some very strong friends that can help sometimes in bringing things about, let's try it here. If it works here we will know it will work somewhere else. [29]

|

| The completed Gateway Arch Parking Garage, from Washington Street on the north side of the Arch grounds, April 1987. NPS photo. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

jeff/adhi/chap1-2.htm

Last Updated: 15-Jan-2004