|

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

Administrative History |

|

|

Administrative History Bob Moore |

CHAPTER TWO:

The 70mm World Odyssey Theatre

Original plans for the development of the visitor center at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial called for the construction of two theaters. The 325-seat North Theater was opened on May 13, 1972, for the premiere showing of Charles Guggenheim's prize-winning film "Monument to the Dream," detailing the construction of the Gateway Arch. A second film, "Gateway to the West," 30 minutes in length, was first shown to the public in the North Theater on August 12, 1975. The North Theater was officially renamed the Tucker Theater, in memory of former St. Louis Mayor Raymond R. Tucker, on April 13, 1976. [1]

Due to a lack of available funds, construction of a second or "South Theater" was postponed, although the location was excavated for future use. The concept for this theater, to be named in honor of former St. Louis Mayor Bernard F. Dickmann, grew from the plans of Superintendent Jerry Schober to involve the community in park programs. Schober recalled:

|

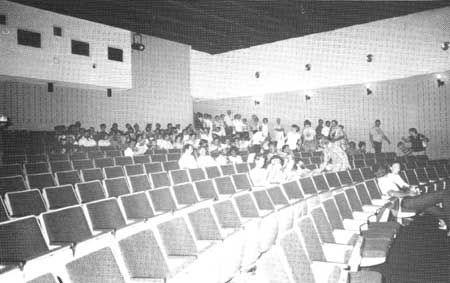

| Tucker Theater, August 1980. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

We felt that since this was public domain . . . the public here in St. Louis would be able to utilize some of the facility to carry out programs that are of interest to them. All we would ask . . . would be that they would at least pick up the expense. It was not to be a money maker for the Park Service. So we began to contact local arts groups that might be interested. The Repertory Theater, the MUNY, the Fox; . . . all together I think thirteen groups showed up. We took them around and showed them the facilities and asked what kind of design [they would want for a community theater], what kind of lighting and all would suffice. Then we would all go to lunch and see if there were any possibilities that we might be able to provide this facility for them.

It was rather interesting. Every time you talked to the ones with the ballet the stage was not right, you talked to some other classical [group] the lighting was wrong, and it looked like it would take thirteen different ways of trying to design this theater to conform to all of them. At about that time the chairman of the MUNY, which is the largest outdoor theater in the country, [Edwin R.] Culver, turned to me and said, "You know what you need is an IMAX." [2] I had never heard that word in my life. . . . But I found out it was a type of motion picture that you became a part of and you couldn't get away from it without closing your eyes and almost stopping up your ears. . . . I later contacted the IMAX company, at which time [we] changed the whole design and thought for this theater. [3]

Bi-State Development Agency, at the request of Superintendent Schober, expressed an interest in financing the new theater, now planned as a wide-screen facility capable of presenting a movie in the 70mm IMAX format. Preliminary concept plans and cost estimates were completed during 1987. Technical and legal questions were researched, and discussions held within the Midwest Region of the National Park Service (NPS) and Denver Service Center (DSC) regarding the scheduling of studies and monitoring of construction activities. JEFF would be the first park in the system with such a facility. Funding was tentatively selected, in agreement with the Bi-State Development Agency, as the sale of Series E General Revenue Bonds with debt retirement secured by the Arch tram revenue. As with past projects such as the parking garage, there were no federal funds involved. [4]

Rock Removal

Construction of the new theater required the removal of additional rock from the area of the earlier excavation to accommodate the huge screen. To determine whether this would be feasible, engineers from the Denver Service Center visited the site in May 1987. They concluded that the work could be done without any detrimental effect to the Gateway Arch complex. In meetings between Bi-State and NPS officials, it was decided that DSC would provide project supervision services. An independent A/E consultant would determine the effect of the construction on the Arch, the subterranean structure, and the surrounding grounds and utility systems. Bi-State agreed to finance this study, and in August 1988 Woodward-Clyde consultants began a geotechnical analysis. [5]

The study indicated that with proper precautions, approximately 1,200 cubic yards of Mississippi limestone could be excavated with no impact on adjacent structures. Once this determination was made, the next decision involved the method to be used. Conventional means, such as blasting, were not possible, for the obvious reasons regarding visitor safety and the structural integrity of the Gateway Arch. In September 1988, park officials forwarded a proposal to the Midwest Regional Office from the University of Missouri-Rolla (UM/Rolla), for a demonstration project to remove approximately 2,000 cubic yards of limestone using a high-pressure water jet. In February 1989, NPS architects attended a demonstration of the method in Rolla, Missouri, and concluded that it would be effective for the Arch project. Among the advantages of the water jet which influenced this decision were that it produced no loud noises, dust or fumes; no large equipment was required; it fragmented the rock into manageable pieces; and it did not damage the existing walls. A contract was drawn up between Bi-State and UM/Rolla, with the Park Service serving as reviewer and evaluator. [6] "We wanted to go to the wide screen dimensions," recalled Superintendent Schober, "and to accomplish this we only had this one small space."

|

| Excavation on the site of JEFF's second theater project, 1990. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

It would encompass going fifteen feet down below the Arch into bedrock, and also working on a structure that was already completed, and we would have to utilize the back halls of this structure to carry out all the stone and clay and dirt, and move in any equipment. . . . And these are the same hallways [in which] my people had to carry on business as usual. It would be a tremendous undertaking and a real imposition on the staff. But when we looked at what the benefits might be, we felt that it could be worthwhile. [7]

|

| High-pressure water jet used in the excavation of the second theater, 1990. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

In September 1989, UM/Rolla and the NPS concluded a Memorandum of Agreement that identified and described the duties of both. The University would design, fabricate, install, and maintain the cutting and splitting (CUSP) equipment, and provide the necessary training and technical assistance to students, hired as temporary NPS employees, who would perform the work. At the same time, University personnel continued their research and development to improve the CUSP process. [8]

Unexpected delays were encountered due to a Department of Labor determination regarding insurance and liability, which negatively impacted the proposed cooperative agreement between UM/Rolla and the NPS. The agreement had already been approved by the federal solicitor, but the Department of Labor problem was only overcome when it was decided that UM/Rolla employees would be paid under a grant. Non-federal funding was available, in the amount of approximately $750,000, to complete the fiscal year 1990 work schedule. [9]

The architectural firm of Cox/Croslin and Associates, of Austin, Texas was engaged by DSC on a $200,000 contract to design the South Theater in 1990. This firm had an indefinite quantities contract with DSC, and was "on retainer" for architectural work in the Midwest Region. The preliminary design was completed in March 1991. Excavation of the theater space was begun under a $377,867 demonstration program arrangement with the Rock Mechanics Department of UM/Rolla. Seven engineering technician students were rotated into employment on the project as temporary park employees under the administrative supervision of the JEFF Heating and Air Conditioning (HVAC) crew foreman, John Patterson. They operated the equipment and performed rock removal, using a monorail system to carry the debris across the theater space and out of the building. At first there were problems with the water jet technology. The system worked inefficiently on-site, according to John Patterson. "The way it performed in the lab and the way it performed on the job were totally different worlds. First of all, they had clean water in the lab. The plan was to catch the water in a sump, and reuse it, but the contaminants in the water prevented this. Secondly, the guidance from the professors was fragmented and poor, and the HVAC crew found themselves helping more than supervising. Finally, we got the bugs worked out of the system." [10]

Foundation design and consulting services were provided by Woodward-Clyde Consultants, St. Louis, under contract to the Bi-State Development Agency. [11] A $66,000 contract with Woodward-Clyde for rock-bolting and dewatering as well as a contract for rock hauling were also awarded; by the end of 1990, approximately $628,000 of non-federal funding had been provided toward the planning and initial construction of the theater. [12]

Work continued into 1991, as park management entered into negotiations with World Odyssey to construct the first American-made 70 mm — 15 perforation wide screen projection system in the United States for the South Theater. None of the estimated $3 million was federally funded. [13]

Work began on interior features of the theater in April 1992. Back hallways between the theater site and the shipping-receiving area became very busy places during this phase of the construction. Contractor Kozeny-Wagner erected a partition wall to isolate the work area from the lobby of the visitor center. Park employees designed and supervised the painting of the partition wall with a poster announcing the new theater. This work was performed by a group of enthusiastic fifth grade students from the St. Louis school system, who filled in the design sketched on the wall with bright strokes of color, creating a very handsome interpretive display. [14]

|

| The excavation phase of construction nears completion, 1991. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Projection System

While rock removal proceeded, plans were made for the film to be shown in the new theater. The project was once again financed by Bi-State Development Agency. The initial proposal, the creation of an IMAX film, led Superintendent Schober to open negotiations with that Canadian company in 1987. Schober remembered:

IMAX thought if they could get into the national parks it would be a feather in their caps. . . . We found out that secretly one of the vice presidents had been here in St. Louis, because Union Station was thinking about possibly putting in the same type of IMAX presentation. And so I called this young man in Canada . . . and he said he would come by and talk to us. Meanwhile, they had written another letter to Park Service [Director William] Mott. And when he looked at it, he instructed Stan Albright to contact the Arch. He said, "I figure if we can do that anywhere they can do it down at the Arch." And he said, "Tell Jerry to look into it, and if he feels it's feasible, for the Park Service to go into it." And of course we liked this because of the perfect timing. We had already made a contact with them, and so it relieved the Washington Office of having to do any further correspondence with IMAX. . . . For some reason [Director Mott] thought where it was money — raising it or spending it — we got called. He would always say, "Go to St. Louis."

Carpeting the tiered seating area, 1992. NPS photo, courtesy Dave Caselli. And so we started serious negotiations. Oddly enough, it took IMAX a long time to get back with us. We told them that we were interested in buying a projector. . . . At the same time they were looking at us, they were also scouring across the whole park system to see how many parks were large enough and had enough . . . all-season visitation . . . to accommodate an IMAX. And what happened to our relationship was, by the time they scrutinized the Arch real closely, they were also going to put one in the [St. Louis] Science Center, which was yet to be built. It was going to be about a thirteen million dollar complex. . . . But now you've got to remember this Science Center had no established clientele. It was a little shaky for them, too. . . . [The Director of the Science Center], Dr. Dennis Wendt, thought it was very important that we didn't show the film that they were going to show. Because we told him until we could have a film made . . . we would probably show The Dream is Alive. And he almost passed out. And I said, "Why?" And he said, "That's what we were going to show." And I said, "We are not a competitor. We are going to have a clientele that comes here all the time. Maybe some of them will go to your place, but we don't have to lock in on The Dream is Alive." I really thought that Grand Canyon might even fit better. So we thought along those lines. But still, in the back of our minds we wanted to make our own film. That way we could maintain all the funds, and not have to pay anyone else for rentals, which are quite costly. [15]

By July 1987, it was decided that the government would hold title to the theater; that Bi-State would be responsible for financing, construction and operation; and that IMAX would provide technical assistance during the design, construction and operation of the theater. IMAX would also produce a film for JEFF on westward expansion, and equip the theater with a screen, sound system, projection system, and other related equipment. [16]

In July 1988, a letter of intent from the NPS specified that the name IMAX would be allowed in the theater name, and that the movie could be leased to other IMAX theaters after two years. The NPS made plans to advertise for a treatment, production plan, and cost breakdown for a film on westward expansion. Harpers Ferry Center would serve as executive producer, at an estimated cost of $300,000, which would be paid by Bi-State. [17]

With the project well on its way, a disagreement developed between IMAX and the Park Service regarding the arrangements for the projection equipment. IMAX proposed leasing it to the park for $1.6 million up front plus a percentage of the gross ticket sales, while warranty maintenance and service of the projectors, screens, and the sound system would be available for an additional $50,000 per year. This was unacceptable to Superintendent Schober, since JEFF wanted to buy the equipment outright. In a letter to the IMAX company in July 1989, Schober explained that neither the NPS nor Bi-State could enter such a long-term lease agreement. He said that IMAX had implied in earlier negotiations that the projection equipment would be sold outright. In reply, the company stated that it had never been its practice to sell equipment. [18] Superintendent Schober recalled:

We were working under the assumption that IMAX would sell a projector to us. IMAX at the same time found out that there are times when we can get up to five thousand people an hour under the Arch, and that the wait at many times is up to four hours to go up in the trams to look out of the observation deck at the top of the Arch. . . . And just like that [the IMAX representative] said, "Oh, by the way, there is just one little catch to what we've been talking about." And I said, "What is that?" And he said, "We won't be able to sell you our projector. Way back we had a company policy change . . . and we have to lease, we can't sell." I said, "Well, Uncle Sam will buy. We are not going to lease. And he said, "Wait, wait, wait, let me tell you, this is a great relationship. Jerry, you are going to get so many benefits from this."

Installation of the marble facing, exterior of the projection booth. NPS photo courtesy Dave Caselli. Now, by that time he's never given us a price, but we knew what other people were paying, and IMAX was getting pretty close to a million and a half dollars for the projector. And [this man] said, "Here's what we'll do; I think you'll really like this . . . " A million five down, and 25% of the gate at every showing. And boy, they would get us the best up-to-date film, they would distribute it everywhere — of course fifty-five thousand dollars for maintenance of their system, "but what you get Jerry, is our guaranty that every time there is a technological improvement to the system it's going to be installed in your system. You get the latest in everything, you have the ability of IMAX which is world-known to do advertisements, you'll be known everywhere, we'll increase your visitation." I'm still thinking about, what did you do with my million five with which I was going to buy a projector and not have to share [anything] with you, and how are you getting into my pocket for 25% of the gate? Quickly, and I only work in simple terms, I put ten years times what we had estimated he would make at twenty-five percent and I figured they'd walk away with eight million dollars. At that time I showed him how to get out of my establishment so he could catch a plane back to Canada.

We can tell you, we were courted and threatened and everything else by IMAX because we abruptly left them. But we found out that the copyrights [and] patents were slowly falling off of their machinery. [19]

After the talks with IMAX fell through, the NPS began considering other possibilities. In July 1989, Omni Films of Sarasota, Florida, met with Superintendent Schober and Jennifer Nixon of Bi-State to discuss their "Magnavision" system. In September, Schober, Nixon, Assistant Superintendent Gary Easton, and Jerry Ward of Harpers Ferry Center traveled to Florida to see a demonstration.

In October 1989, the Iwerks Company made a proposal to JEFF to set up their "Iwerks 870" system. For $395,000 they would provide the projection and audio equipment, as well as technical consultation and support for film production.

In 1991, after considering many possibilities, JEFF decided to purchase the "World Odyssey" 70mm system from NJ Engineering of Los Altos, California. A sophisticated sound system was licensed from THX®, a division of Lucasfilms, in San Rafael, California, and a completion date for the theater set for January 1993. [20]

Film Production

In 1988, JEFF began to consider options regarding the creation of a 70mm wide-screen film, designed to be shown in the park, telling the story of westward expansion. In Superintendent Schober's words:

To do this we talked with Jerry Ward, the head of the motion picture division [at] Harpers Ferry. And Jerry came out and said, "I think it would be great if you made your own film." And he gave us some good suggestions. We could [invite people] to come in and give us their scenarios, . . . how much it would cost, and how long it would be, . . . [but] he said you will be jurying people forever. [Ward suggested that specific filmmakers should be selected and offered the option of competing for the 70mm film commission]. . . . Well, we knew that Charles Guggenheim had made Monument to the Dream which has been very, very successful. We knew Greg MacGillivray had made To Fly, at that time the most viewed [IMAX film] ever because it was at the Smithsonian. We knew Keith Merrill, and they told us he would be out of the ballpark fee-wise, because he was so well-known and [in] such great demand . . .

Jerry Ward said, "What would you think of George Lucas? . . . Why don't you see if he is interested?" Now see, a smart person would say, oh, you're kidding, he's not going to fool with us. So, the dumb one got on the phone and called up and said "I'd like to speak to George Lucas."

They said, "You would?"

I said "Uh-huh."

"Sorry, he's not available, would you like to speak to the senior vice president of Lucas Productions?"

And so I spoke to this gentleman, telling him that I understood that George Lucas was interested in making [a 70mm film]. And he said, "Why would he be interested in that? We've already done that."

And I said, "You never made a full length 70mm film on your own."

"Well, we do . . . the illustrations, and the sound, the light, and all the new technologies that you need for them, and we've done some filming for them." And he basically told me that George Lucas was interested in doing what George Lucas thinks of. And I think when you get to his status in the world you ought to do it that way. But he said, "Since you called — you say it's going to be in the Arch and be viewed by millions every year?"

"Yup."

"There's a young man here, who has made quite a reputation, and he's been wanting to make a film; . . . Why don't you talk to Ben Burtt?"

So I got his number and called Ben up. And Ben said, "I'd like very much to do a scenario, we'll do a lot with sound and lights, but we'll do the westward expansion using the scenes they went over, the Indians, the covered wagons, and let all that speak for itself. We won't have a central character, it's not going to have a narration. It's going to be an experience." . . . I found out that he had won four Oscars by that time. [21]

In November 1988, Bi-State agreed to pay $8000 each to Ben Burtt of Sprocket Systems, a division of Lucasfilms, independent filmmaker Charles Guggenheim, and Greg MacGillivray of MacGillivray-Freeman Films, to develop proposals for a treatment, production plan, and cost breakdown for the production of a 70mm, large-format motion picture on the westward expansion of the United States, to be no longer than 25 minutes running time. [22] Schober continued:

Now, why we did it this way is that we now owned the finished product. Even if [a contender] didn't win, [we owned their] thoughts. If we wanted to . . . use a good point here, a good point there, we could put them together. And then we sat down and juried them out. . . . The jury consisted of Jerry Ward of HFC, Jennifer Nixon of Bi-State, Chief of Interpretation of the Midwest Region Warren Bielenberg, Gary Easton, and myself. . . . Everybody sent us one. I want to tell you, some of them were great. Guggenheim's would have made a great mini-series. There wasn't anything wrong with Keith Merrill's. But the most exciting one was still Ben Burtt's. And one of the key ingredients to that was he even went and got John Williams, four-time Oscar winner, to do the music; conductor of the Boston Pops, the great arranger. Can you believe, John Williams agreed to score the whole film, [and] that he wanted to use the St. Louis Symphony. . . . I thought that would be a great coup. And as we judged them out it was difficult, but we selected Burtt's. I think before we could even get in there and tell him that he was the winner of this whole thing and send him his check, he had already won his fifth Oscar. [23]

In December 1989, a contract was signed with Lucasfilms for the development of a script for a movie to be titled "Gateway America." Ben Burtt and Laurel Ladevich, film editor for Sprocket Systems, were set to direct the film. They were also to research and define all locations and to prepare a detailed budget and schedule for production. All proceeds from ticket sales were to go to JEFF. [24]

Once this contract was in place, there still remained the matter of raising the estimated $4 million necessary to produce the movie. Schober hoped to line up a corporate sponsor, but by June 1990 no one had volunteered to finance the project and the deal with Lucasfilms was canceled. It had been hoped that the fame of the California company would attract investors, but several problems arose. Costs escalated to $4.5 million, and LucasArts wanted distribution rights to the movie, interactive video rights and other rights and reservations which JEFF was not ready to resign. [25] "I still think people don't realize what a good thing [corporate sponsorships are]," Superintendent Schober reflected.

The Smithsonian has never paid for a film. It's Johnson and Johnson, or Lockheed, or Conoco, or someone like that. And the companies have found out that they put the money down to make these [films] which are up in the millions, and at the end of a year or year and a half, they've been paid back. Once you make it, every time it's shown somewhere other than, say, the Smithsonian, every gate you get thirty-five percent of sixty-five percent of what comes back in through that gate. And that represents sizeable money. Some people charge as much as $7.50 a person. And you figure some of those, like the Smithsonian . . . only charge two dollars or two and a half. But look what they did in volume, too.

We just felt that it would be tremendous. And I think it may still come to fruition. I can hardly wait to see that theater open up. . . . [26]

|

| Completed interior, World Odyssey Theatre, 1992. NPS photo courtesy Dave Caselli. |

Park officials decided that once the theater was finished, other large format 70mm films such as To Fly and Grand Canyon: The Hidden Secrets could be shown until a westward expansion film was produced. [27] It was anticipated that the wide-screen theater would provide a tremendous educational and interpretive opportunity to an estimated 900,000 annual visitors, who during the busy season might wait as long as three to four hours for a tram ride to the top of the Gateway Arch. In addition to the Museum of Westward Expansion, ranger-led tours and the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association museum shop, the film would provide a further interpretive opportunity for a ready-made audience. [28]

|

| Completed entrance to World Odyssey Theatre, 1993. NPS photo by Kris Illenberger. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

jeff/adhi/chap2-2.htm

Last Updated: 15-Jan-2004