|

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

Administrative History |

|

|

Administrative History Bob Moore |

CHAPTER THREE:

The Veiled Prophet Fair

History of the Event

The annual Veiled Prophet Fair (VP Fair) is an event which contributes to the unique character of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. It is also one of the most controversial and unusual aspects of the memorial's recent history. Billed as the nation's largest Fourth of July celebration, with attendance figures in excess of 2.5 million people annually, [1] the VP Fair is held on the grounds of a national park, with most of the necessary costs and repairs paid for by the local Veiled Prophet Fair Foundation. Air shows, live music, nationally known celebrities, educational and family attractions, food, and fantastic evening fireworks displays attract visitors from across the country and around the world.

The VP Fair has its roots in the agricultural and mechanical fairs held in St. Louis beginning in 1856. These fairs had lost their momentum by March 20, 1878, when Charles Slayback, an influential grain broker, invited St. Louis businessmen to a meeting at the Lindell Hotel. At the meeting, Slayback proposed an annual event similar to the New Orleans Mardi Gras, hoping that such a festival would spark public interest and boost attendance at the October harvest fairs. [2]

To stimulate curiosity in the proposed event, Slayback's brother Alonzo drew upon a mythical character created by Irish poet Thomas Moore in 1817, the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan. Changing Moore's legend to suit the needs of promoting the fair, Alonzo Slayback's Veiled Prophet was no longer a "war-mongering trickster," but an entrepreneur who wanted to share his personal happiness with another part of the world. In Slayback's version of the legend, the Veiled Prophet traveled over the globe, finally stopping in St. Louis, which he made his adopted city. He believed the citizens of St. Louis to be much like the people of Khorassan, contented and hard-working. He informed city officials that he would return in one year to share his happiness with them, telling them that they must prepare for his arrival. [3]

Such a "hook" for the enticement of the public appealed to the businessmen, who formed a secretive, elite society called "The Mysterious Order of The Veiled Prophet."

Plans were made for an evening parade and a grand ball, the first of which were held on October 8, 1878. The event was enormously popular, with more than 50,000 people lining the parade route that first year. The Veiled Prophet parade and ball became annual events, as well as a traditional part of life in St. Louis. [4]

In the early 1980s, it seemed logical to expand the Veiled Prophet event beyond a parade, changing its scope from a city-wide celebration to one worthy of national attention. Robert R. Hermann, a St. Louis businessman and civic promoter, also wanted to elaborate on the July Fourth "Freedom Festival" riverfront fireworks show, traditionally sponsored by St. Louis' Famous-Barr Stores and KMOX-AM Radio. While very popular, the Freedom Festival offered little food or entertainment. [5]

Superintendent Jerry Schober recalled the beginning of JEFF's involvement with the fair, which began soon after his arrival in the park:

Within probably five weeks after I got aboard, the mayor of the town asked if he could come visit me. And it was set for nine o'clock, but by nine o'clock there was no sight of him. I finally found out that he thought my office was down under the Arch. And so he had actually waded through the mud [the grounds were torn up due to extensive landscaping at the time] to get there with these big open trenches. And when he came in we made a little small talk. And all of a sudden he said, "We want to put on one of the largest events in the United States." A guy by the name of Robert Hermann had been doing a lot of research on this in different places. They did not know exactly how they wanted it, but they wanted it in the largest open area next to the river. And of course that was the Arch grounds. . . I said, "Mr. Mayor, I think it is lucky you did not fall in one of those trenches coming over here. . . I don't see how we can do it. The landscaping won't be done . . . "

The only way I could put him off was by talking to him in his office. . . . The mayor was still rather insistent. So I said, "Well, Mr. Mayor, like I told you on the last visit, I certainly did not want to come here to start telling you no. So I offer you another suggestion rather then tell you no. As soon as you send me a letter saying that you will assume all the liability for such an event, if anybody is injured, hurt or anything else, that the City of St. Louis will take care of it, and if it satisfies our solicitor, I will certainly give you a permit for this big outing."

He said, "Well, I've never been asked anything like that."

"Well, that makes two of us because I have never been asked to put on an event like you are talking about either."

So we finally agreed that we wouldn't have it that year. And so it was the following year that we had it, which was still, I think, a year too soon. [6]

In 1981, Robert R. Hermann recruited 100 community leaders to organize the first Veiled Prophet Fair to be held on the Mississippi riverfront. The NPS issued a special use permit to the City of St. Louis, which, in turn, issued the permit to the VP Fair Foundation. The fair opened on Saturday, July 4, 1981, following the previous evening's VP Parade. Fifteen community and charitable organizations staffed food and beverage booths, and approximately 3,000 volunteers managed entertainment activities around JEFF's grounds. Nearly a million people attended the fair. The money that was raised was used to organize and stage the second fair in 1982. [7] Superintendent Schober recalled:

[The] Fourth of July celebration . . . ran sometimes for two days, three days, and eventually we even had some that were four-day affairs. But we did things totally different than I had done when I was working in Washington D.C., when I had the monuments and memorials. Here, I required the VP Fair and the City of St. Louis to accept the liability and also to accept property damage. They had to have insurance and I had to have proof of such insurance in my hands . . . ninety days before the fair started, or we would not have it. [8]

Over the next several years the fair continued to grow in size. In 1982 approximately 3 million people attended; by 1983 "America's Biggest Birthday Party," as it was being billed, was attracting nearly 4 million. It also received national attention with coverage from the NBC television network in 1984, and was the location for major television specials on ABC in 1987 and 1988. The Veiled Prophet Fair experienced a metamorphosis during the 1980s, from a rather rowdy celebration with a sometimes unruly crowd to a family-focused event with an emphasis on particular themes such as "Education" and "Parks USA." [9]

Minimizing the Damage

Due to the evolving nature of the fair, the early years were trial and error ones for park officials. As time went on they began to learn how best to manage such a major event. A primary area of concern for the NPS was the protection of the grounds and natural resources of the site. Strict limitations were developed over time that minimized the adverse effects of the early fairs, when the grounds and trees sustained heavy damage from the use of vehicles and equipment to set up and take down booths and stages, and the presence of large concentrations of people.

In order to use the JEFF grounds, the VP Fair Foundation applied to the NPS, through the City of St. Louis, for a special use permit. Typical provisions included the installation by the VP Fair Foundation of fences around all areas with shrubs and ground cover; the prohibition of motorized vehicles on the grounds between 9:00 AM and 10:00 PM, in the interest of safety; proof of adequate insurance coverage, with the NPS named as coinsured; and the agreement on the part of the foundation to replace all damaged trees and shrubs, as well as responsibility for re-sodding and reseeding of grassy areas. The NPS, through the superintendent, reserved full veto power over any activity deemed inappropriate. [10]

The administration of these regulations was largely successful. Although the memorial grounds were heavily impacted during particular years, such as 1982 and 1987, when the 3-day event was marked by almost continuous torrential rains, the VP Fair Foundation has usually honored its promise to repair the annual damage. Superintendent Schober lamented:

|

| Clean-up from the 1982 VP Fair. Courtesy John Weddle. |

[The] first year we started the repair of the grounds, but we thought it would be an insignificant amount. I never really asked how much it cost them. . . . We finally agreed on a contractor who laid the landscaping out. And then we found a landscape architect who we both respected, they paid for him, and he came out to assess what had to be repaired. . . I know one year [1982] it had to be a quarter of a million dollars worth of repairs. . . . We even had to redo the irrigation lines underneath. [11]

|

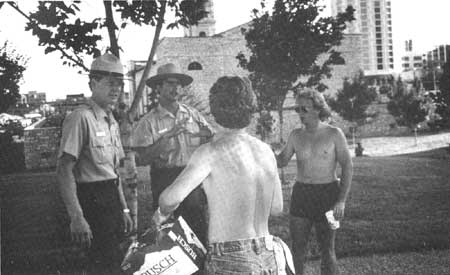

| Patrons of the 1982 VP Fair with liquor they brought onto the grounds. NPS photo. |

In addition to protecting the grounds and natural resources, visitor safety was a major concern, both for the VP Fair Foundation and the NPS. Some fairgoers opted to bring their own liquor with them onto the grounds rather than patronize the beer vendors onsite. Problems resulted from the excessive consumption of alcohol and shards of glass which littered the park where bottles had been carelessly discarded. In response to the problems caused by alcohol brought onto the grounds and smashed glass containers, the city passed an ordinance prohibiting both in 1985. [12] This law resulted in an elimination of some of the rowdy element in the crowds.

Vehicle use on the grounds during the fair was restricted, also out of concern for visitor safety. Motorized vehicles were always prohibited during peak hours of visitation, with the major exception of golf carts and emergency vehicles. The golf carts were used by fair "marshals," the volunteer workers, for transport from one area to another. But as the size of the crowds increased over the years, even the golf carts became potential safety hazards. In 1989 the NPS decided to prohibit their use at future fairs by any but Emergency Medical Services personnel. [13]

By 1990 experience and advance planning resulted in effective management of the VP Fair. Workable systems were in place to assure safe and smooth running operations. An average of 20,000 volunteers staffed the booths each year. [14] The NPS maintenance crew perfected the repair of the grounds to an almost scientific efficiency. [15]

Visitor Protection

A major concern for the NPS regarding the VP Fair was the additional costs incurred due to the need for increased law enforcement personnel. The large crowds of fairgoers made it necessary for the NPS to bring in special event teams from other park areas. This meant paying travel and overtime expenses above and beyond normal budgets. In 1982 the estimated cost to the NPS for these expenses was $50,000; by 1984, with the growth of the fair, costs had risen to $106,000. To meet this need, special appeals were initially made to the Emergency Law and Order Fund. [16] In 1985, however, the decision was made in the NPS Washington Office that such funds would no longer be available to cover the costs of the fair. After 1985 all necessary funds would have to be budgeted or provided for by the city or the VP Fair Foundation. [17] This decision led to the development of a stipulation in special use permits issued for the fair, requiring the payment of all the NPS' extra expenses. [18]

Costs formerly covered by federal money amounted to $90,000 in 1987, and to receive its permit the VP Fair Foundation was required by the NPS to pay in advance. [19] The foundation was also charged for all subsequent expenses beyond the original estimates. In 1988 this amounted to more than $25,000. Despite some difficulties in collecting these additional charges, in each instance the foundation eventually paid in full. "We felt that we had to have an increased number of rangers out there to protect the grounds, even though we had up to five hundred St. Louis city police," recalled Superintendent Schober.

|

| Law enforcement rangers at the VP Fair, 1982. NPS photo. |

These [city police] did not recognize their duty as protecting trees and visitors. And I think I can see it. They received compensatory time, not overtime pay, for working the fair. If tomorrow morning I wanted the rangers to be down at city hall and they said "Why are we down here?," and we said, "Well, they are going to have a Strassenfest and I want you to protect city hall." They'd say what the devil are the city police doing? So, you had a little bit of this. The police were good for a deterrent. You always had the potential, the possibility, of a riot breaking out or something. So, we brought in . . . twenty five or thirty rangers, which we paid out of emergency funds. . . . [We had] to bring [people in] from everywhere, [because] a lot of parks had things going on around the Fourth of July. Some people didn't want to let them go. So quite often we had to pay for people to fill in behind them. The air fare got expensive. I suggested to the VP Fair that they go to TWA and see about getting some passes, and actually at times they gave them as much as $25,000 worth of freebies. I didn't realize how complicated it was until we got into it because TWA does not have a reciprocating agreement between every airline. And we'd be bringing some [rangers] out of Washington state or somewhere, and they'd have to catch a little hop, and then catch another line. . . . Almost consistently Don Morrison, one of the vice presidents of TWA, took it upon himself to sit down and oversee these arrangements.

It was an interesting learning situation for the rangers that came in. I remember going to Isle Royale and running into one of the wilderness rangers and we recognized each other because he had been [at the VP Fair] just a few months before. And I asked him what the experience was like. He said at first he just couldn't picture it, but he said now he wouldn't take anything for the experience he got. . . . You know, you had an opportunity to interact with just mobs of people. I would say maybe three to four hundred thousand sometimes at one time in a given area, when the big performances were going on. And our first two years, we had too many performances on the main stage. Something was going on the main stage every hour, from eleven in the morning until nine at night when the fireworks would start up. Those were tough times. But during the years we have sophisticated it. . . [20]

"A Gift or a Desecration?"

Although the park was praised for its handling of the VP Fair in a 1982 operations evaluation by the Midwest Regional Office, it was noted that within the park staff there was "a definite dichotomy or cleavage regarding the VP Fair. There are significant numbers of personnel who oppose this type of activity on either philosophical grounds or because of the impact that the activity has on operations and operating problems." It was suggested that park management solicit a grassroots staff input and response regarding the 1982 VP Fair. [21]

The orderly, carefully planned and managed fairs of the late 1980s and early 1990s give little indication of the troubled early years of the VP Fair event. A closer look at one of the earlier fairs, that of 1982, stands as a good indication of some of the massive problems presented by such a large event, and of the destructive impact of the early fairs to the resource, which disturbed the staff of the memorial as well as the general public.

The 1982 VP Fair was fraught with problems from the start. It was only the second year of the fair, and the first time that it had been conducted as a large-scale event. The fair was extended from the grounds of the Gateway Arch to the Old Courthouse, where cultural organizations set up exhibits. Attractions were located at Laclede's Landing, north of the park grounds, and beyond, to a field where athletic events were staged.

"We hope we will be able to spread the people out," said the fair's administrator, Charles H. Wallace. "With the number of events we'll have going on, we hope people will feel they can wander around the grounds and not have to park themselves just in front of the main stage like they did last year." There were eight satellite stages to help discourage visitors from clumping in one area. The 1982 VP Fair had an operating budget of $3 million. [22]

|

| Enormous crowds at the 1982 VP Fair brought their own liquor and waded illegally in the park's reflecting ponds. Photo courtesy John Weddle. |

William E. Maritz of the VP Fair Foundation Inc., quipped in February, "We have decided that there will be no rain. . . . Therefore, there will be no need for contingency plans in the event of rain." [23] However, rain fell intermittently throughout the event, and combined with another weather problem, extreme heat, to afflict several fairgoers with heat exhaustion.

Immediately after the fair, which drew an estimated 3.75 million people, hundreds of workers from the National Cleaning Company began fanning out over the grounds, picking up trash. City fathers were pleased by the huge turnout, [24] but the grounds were a mess, which upset JEFF Facility Manager Bob Kelly. Tom Adams, Vice President of National Cleaning, was quoted as saying that "the place is going to look like it used to." Bob Kelly felt otherwise, and told the newspaper that it would take at least a year for the site to return to normal. "And there is some damage that may not show up for several years. . . . I saw the lights shaking, day after day, in the visitors center under the Arch. It wasn't built to take that kind of pressure. I don't know what the long-range result will be." In 1981, the VP Fair Foundation was charged only $18,000 for repairs, with the Park Service performing two-thirds of the work themselves. Although the VP officials pledged to return the park to "the way it was," concerns among members of the park staff ran deep.

All the goldfish in the reflecting ponds on the grounds were killed over the weekend of the fair. The grounds were trampled to the point of killing all the vegetation over large areas. Bob Kelly continued, "The main thing is that they are trying to make a fairgrounds out of a place designed as a people park. . . . Sure, some of the parks in Washington are used that way, but they have access roads on either side and they were designed for that sort of pressure.

"There is only one service road for trucks in the whole Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. And what we have seen is 40-foot over-the-road semis being driven over what are sidewalks, pedestrian passageways. We told the VP people not to bring in these big trucks, but they didn't listen." Over 50 of the new Rosehill Ash trees were severely damaged by the big trucks, and deep ruts edged many of the walks. A pool of mud marked the area in front of the main stage. "The area is very delicately graded, sort of corrugated with drainage tile under the lower areas. That is going to have to be completely regraded, and it is going to be a lot harder than it was in the beginning because there is an irrigation system 14 inches underground," said Kelly. [25]

Executive Director Charles Wallace of the VP Fair Foundation responded by hiring a consulting engineer to assist the Park Service in restoring the grounds. Plans were made to further spread out activities for the 1983 fair, even to the extent of considering nearby Busch Stadium for some of the more popular music events. "Take the Elton John concert," Wallace said. "I'm not a bit sorry we did it. We had to experiment with things like that. But the people who came to see Elton John brought their own food and beverages, kept other people away and created a big mess." [26]

JEFF Superintendent Jerry Schober expressed doubts about the future of the fair on the Gateway Arch grounds. "I don't think by any fashion could this be an annual event," he told the media. Schober suggested shortening the event, or scattering the activities throughout the city and county to take the burden off the park. Concerns were voiced especially over the national character of the site; that the event was fine for St. Louisans, but that other Americans who came to see the site a few weeks after the event would view an eyesore, not a national park. [27]

The destruction to the grounds was not the only concern. Fights broke out in scattered places on the grounds, and two people were killed in a shooting incident near the wharfside McDonald's restaurant east of the park. [28]

St. Louis citizens suggested, in letters to the editors of the local newspapers and to Superintendent Schober, that the venue of the VP Fair be switched to St. Louis' enormous Forest Park. Especially galling to senior citizens was the lack of shade trees on the Arch grounds in the early 1980s. One letter noted that "people hoisted makeshift tents" on the grounds. [29]

"The reflecting pools were not meant to be used as swimming pools."

"A beautiful green lawn is a quagmire of mud, trees are dead, an expensive irrigation system is ruined — so the VP Fair can rival Mardi Gras. Is all of this damage to a national park acceptable because the VP Fair Committee is willing to pay for it? Do we allow our children to vandalize or destroy property as long as their parents are willing to pay for it? What a waste of time and money — and what a horrible lesson in values!"

"Is the death of two young men and the need for police to remove a bridge walker success? Would the fair have been a lesser success had four died and the bridge walker drowned?" [30]

"It seems totally inconsistent to me to spend literally years of work landscaping the Arch grounds and then destroy it in three days!" [31]

"Realistically it would not be to St. Louis' advantage to use the Arch area for an annual binge at the expense of ruining it as a tourist attraction for the rest of the year." [32]

|

| The Arch grounds, 1982 VP Fair. NPS photo. |

Perhaps the most effective letter came from a woman who worked as a volunteer on the grounds:

There are things disturbing to my soul. One is a question of whether creating the largest 4th of July celebration in the nation was a gift or a desecration. For three days the VP organization gave St. Louisans what they wanted; but they were all so young or young at heart. Did they know what was good for them?

I was helping a church that was on the brink of financial disaster that was given an opportunity to earn a 15 percent commission selling VP Beer. The second day I sold beer all day. The crowd grew until it was a sea of humanity, flowing past not knowing where it was going or why.

Millions came to see Bob Hope. They saw him but they didn't laugh. They were preoccupied with themselves and their beer. By nightfall I was terrified to leave the sanctuary of our booth; so I stayed until the people were gone. I walked out over a sea of trash at midnight.

On the third day I had to go back. I couldn't leave my friends alone with Elton John and the heat. It was a rare opportunity to have a cold beer concession in Hell and live to tell about it. It was beyond description: The trash, the heat, the mud, the broken glass, the broken trees, the constant press of exhausted humans.

After Elton John the crowd dissipated and we could see the desecration of our national park. [33]

|

| Arch grounds, 1982 VP Fair. NPS photo. |

The overall impression on the part of the VP Fair's backers, however, was one of success. The fair made a profit of $150,000, even after reimbursing the Park Service with $120,000 for damage to the grounds. It was felt that the fair was experiencing growing pains, but that problems could be brought under control with some adjustments. Committee members even began to look toward 2004, and a repeat of the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, to be held in Forest Park, site of the original fair. The annual VP Fairs could serve as "test runs" for a world's fair. [34]

After the passage of years and some distance from the 1982 Fair, especially considering the subsequent success of fairs on the park grounds, it is difficult to assess the tough management decision which faced Superintendent Schober in the latter part of 1982.

|

| Aftermath of the 1982 VP Fair; foot of the Gateway Arch. NPS photo, Midwest Regional Office. |

Although he decided to issue another two-year special use permit to the VP Fair Foundation, he forbade the use of trucks on the grounds, and requested that alternatives be considered to the set-up of the main stage directly under the Gateway Arch. He also forced the arts and crafts booths off the grounds and onto the city streets on three sides of the memorial. Busch Stadium was used for the big-name music acts in 1983. Security was beefed up, to prevent the violent incidents of the year before. A better system of trash storage, pickup and recycling was worked out, to handle the huge amounts of refuse; more than sixty tons of bottles, cans, napkins, popped balloons and other trash were recovered from the site in 1982. [35]

In 1983, Superintendent Schober said, "We want the park this year to be a backdrop for the fair, not the postage stamp everybody has to stand on." VP President Charles Wallace said, "We want to get back to 1.5 million [people]. We want to spread the fair out, and on the Arch grounds themselves have more umbrella tables and picnic tables for families to sit down and relax." [36] The evolution of the fair from a Woodstock-type rock concert to a family educational outing had begun.

The Importance of the VP Fair

The VP Fair has helped to promote commercial development and investment throughout metropolitan St. Louis, estimated at $2 billion between 1981 and 1990. During that same decade, the fair generated more than $2 million for 93 non-profit organizations, which averaged $220,000 per year raised at food and beverage booths run by local charities. The fair generated worldwide publicity for St. Louis which one source estimated conservatively at $5 million per year, focusing attention on the city as a travel destination and healthy economic center. A study released in June 1990 claimed that the VP Fair generated a regional economic impact of about $26 million annually. This included money spent for hotels, restaurants, parking, entertainment, fairgrounds activities and taxes. The VP Fair became the big annual event for the St. Louis community, an integral part of life in the city. [37]

Originally, the VP Fair Foundation donated a portion of the profit from each year's fair to the community, in the form of a gift to be enjoyed by all. The first gift, a result of the 1981 fair, was the lighting for the historic Eads Bridge. Donations also created the Mississippi River Overlook (1982) and the mile-long Riverfront Promenade, constructed between 1983 and 1985, and co-sponsored by the City of St. Louis. The value of VP Fair donations to the city and people of St. Louis totaled more than $1 million during the early 1980s. [38]

Hosting the fair was not without its problems, however. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the VP Fair Foundation fell into debt by as much as $800,000, which curtailed its benevolent activities and gifts to the city. Because of financial difficulties, the fair was sometimes slow to fulfil its obligation to restore the grounds to their pre-fair appearance. In one instance (1987), the committee reneged on its obligation in this regard altogether. The VP Fair Foundation remained hopeful that profits from fairs which were successful from the standpoint of attendance and good weather would reduce their deficit. By 1990, the VP Fair Foundation's debt reached an apogee of $875,000. By 1992, the debt was reduced to $172,510. [39]

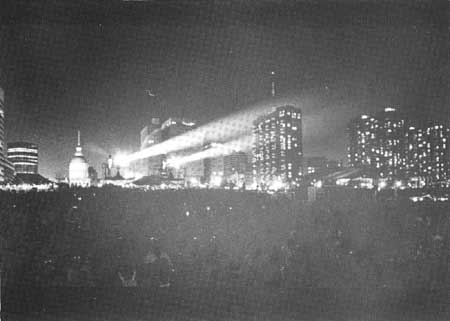

|

| Crowd watching fireworks in the evening, with the Old Courthouse and the St. Louis skyline in the background. NPS photo. |

The Fairs

1981

The first VP Fair was a three-day event, held July 3-5, 1981. With just six months planning time and a tiny budget, [40] it was a miniature version of what would be presented during the rest of the 1980s. Country singer Loretta Lynn was scheduled as the fair's major entertainment, but in a precursor of things to come, was rained out that evening. The rain also swamped the river barge loaded with fireworks, but Sunday night's fireworks, still dry, were substituted and enjoyed by all on the 4th.

The first fair was attended by an estimated 800,000 people, and brought in $113,000, "almost exactly the amount earned at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, according to Price Waterhouse, VP Fair volunteer accountants since 1981." These profits were used as seed money for the 1982 fair, and as the first of the annual gifts given to the community by the VP organization. [41]

|

| Food and craft booth, VP Fair, July 4, 1981. NPS photo. |

1982

The down side of the 1982 VP Fair is detailed above. The official theme of the fair was "The Heritage of St. Louis." Big-name entertainers crowded the stage during the three- day event, including Chuck Berry, Bob Hope, Dionne Warwick, Roy Clark, the Beach Boys, and Elton John, who was spirited onto the grounds disguised as a St. Louis police officer. The fair was attended by about three million people; 3,000,001 counting the baby born on the steps of the Old Cathedral. [42]

1983

More than four million people, the VP Fair's largest crowd of the decade, attended the 1983 fair. Several new attractions were added, including ten satellite music stages scattered about the grounds, a hot air balloon race, an air show, the VP Fair Criterium bicycle races at Busch Stadium and the first annual VP Fair Run. The theme of the fair was "St. Louis . . . Great Moments in Fantasy."

Karen Baldwin, the reigning Miss Universe, led the VP Fair Parade, along with eighty-five 1983 contestants scattered throughout the floats. Performers included Harry Belafonte, the Charlie Daniels Band, the Osmond Family and Linda Ronstadt, as well as 100 additional acts running the gamut of musical styles from Dixieland to rock, jazz, blues, and country. Problems created during the 1982 Fair with musical acts on the Arch grounds were eased by putting the more raucous, big-name acts in Busch Stadium during the day, and acts like the Osmonds on the grounds in the evening. [43]

A steamboat race was held the morning of July 4, when the Mississippi Queen raced the Delta Queen. The race became an annual event. Opera star William Warfield sang "Ol' Man River," backed by the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, on the Mississippi River Overlook. The fair ended with a spectacular 40-minute fireworks display. [44]

The fair had not shed its wild and wooly past, as unfortunate incidents, again along the waterfront area during the fireworks display, marred the occasion. Two stabbings and a shooting resulted in wounds, but luckily no deaths, on July 4. [45]

The VP Fair was a tremendous success, drawing an estimated 4.66 million people, bringing in a gross income of $3.1 million, and turning a profit for the VP Fair Foundation of $275,000. Superintendent Schober was favorably impressed with the small amount of damage to the grounds, and decided to give the green light to a fair in 1984. [46]

1984

Banker Clarence C. Barksdale was general chairman of the three-day 1984 VP Fair, which was highlighted by the participation of the restored Laclede's Landing district just north of the park. Laclede's Landing sponsored a "Fabulous Fifties Fair," which was attended by costumed revelers. A concerted effort was made to spread the activities of the fair over a larger area, and not concentrate them in the park. Charles H. Wallace, president of the VP Fair committee, said that sheer numbers of visitors were not the goal of the fair. "That's not really the purpose of the fair. Keeping it free and accessible to as many as possible is absolutely critical." [47]

A tightrope artist walked a wire between the Clarion Hotel and the KMOX Radio building, at a height of 300 feet, for a distance of three blocks. This, of course, was off park property. Perhaps the most unusual event of the fair was a wedding held in Luther Ely Smith Square, between the Arch Grounds and the Old Courthouse. A VP Fair band entertained an expectant crowd who waited for the bride, 30 minutes late in arriving. Booth vendors from the fair supplied ice cream and cake for the wedding party, including the 90-year-old justice of the peace.

Since the 4th of July fell on a Wednesday, the fair was held on a split schedule, beginning with the VP Parade on Friday, June 29, continuing on Saturday and Sunday with fair activities, and concluding, after a two-day break, with a final fair day on Wednesday the 4th. President Ronald Reagan was invited, but in an election year opted to spend the 4th campaigning in the state of Florida, where the polls did not favor him so highly. [48]

On Monday, July 2, NBC's Today Show broadcast live from the Gateway Arch grounds, and a "mini fair" was staged for the benefit of a nationwide audience. The two-hour show highlighted the city of St. Louis, calling it "a city on the rebound." Mayor Vincent Schoemehl was interviewed, as were other city officials. Chuck Berry and John Denver performed "Roll Over Beethoven" on the river overlook especially for the show. Joe Garagiola took cameras to his boyhood home on Elizabeth Avenue in The Hill section of St. Louis. Gospel music pioneer Willie Mae Ford Smith stood on the steps of the Old Courthouse, and spoke of an ancestor who had been sold as a slave on the same spot in the 19th century. The national attention was a first for the VP Fair, which had unsuccessfully tried to lure the networks to St. Louis since the first fair in 1981. The importance of this coup must be seen in light of the fact that in 1984, the Today Show went on the road just twice each year. [49]

Despite this publicity coup, many St. Louisans remained skeptical about the fair. St. Louis' alternative newspaper, the Riverfront Times, carried an article which refuted the idea that the message about the VP Fair was getting out to the American people. The article stated that the St. Louis media were playing up the event beyond its relative importance on the national scene. "Only one fact is beyond debate: St. Louis received a big zero in national news coverage of July Fourth celebrations. That's a fact, a truism, a statement documented, sadly, by the black ink on white paper that a score of other cities received while St. Louis wasn't even mentioned. All the civic boosterism in the world, all the good intentions, all the overkill daily newspaper coverage can't change this fact: St. Louis' great party was ignored nationally." [50]

|

| Emergency carts on the Gateway Arch grounds, for use during the VP Fair. Courtesy John Weddle. |

Attendance of 3.8 million people unfortunately included unruly motorcycle gangs. The large number of fairgoers who brought alcoholic beverages in glass bottles prompted a city ordinance prohibiting this behavior for future fairs. The fair experienced a good deal of drunken, rowdy behavior from teens, and complaints appeared in the newspapers about the ease with which underage kids could obtain alcohol. Tighter restrictions were placed on beer vendors following the 1984 fair. [51]

Food and beverage sales were up 50% over 1983, with a resulting increase in trash. A major cleanup effort was inaugurated on Sunday night to prepare for the Today Show broadcast on Monday. A group of 200 contract workers, 35 city employees, and 100 summer workers with St. Louis' "Operation Brightside" collected and hauled away 33 tons of trash, working through the night. "Operation Brightside" collected 13,000 pounds of aluminum cans from the weekend, and another 9,000 pounds from Wednesday's activities, netting $4,000 for the citywide clean-up program. Crews recovered a total of 130 tons of trash from the week of activities. [52]

Featured performers included Glen Campbell, Helen Reddy, John Denver, Nancy Wilson, Buddy Rich and Tom T. Hall. NBC weatherman Willard Scott also attended, and served as grand marshal of the VP Parade. [53] The crime rate was low, and the fair was marred by only one tragedy, the suicide of a man from Indiana who jumped off the Eads Bridge. [54] Best of all, the fair showed a profit due to increased food and beverage sales. [55]

A St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorial summed up the change in the VP Fair:

The fourth annual VP Fair had it all — alas, including a long bout of rain that held the attendance down somewhat on the final day, Wednesday, but did little to dampen the spirits of the huge crowd that made its way to the riverfront for the festivities and fireworks. The smooth, professional management of the event was solid evidence that the promoters have developed it from a spectacular if occasionally chaotic attraction to a spectacular show with a minimum of problems. That evolution is the soundest assurance that the fair is here to stay as high quality annual entertainment. [56]

1985

Visits totalling 3.95 million were made during the 1985 VP Fair, which was extended to a four-day extravaganza. This was made possible because the 4th of July fell on a Thursday. The fair's featured entertainment was purposely steered away from rock music and toward more family-oriented attractions. These included Ray Charles, Doc Severinsen with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, Liza Minnelli, and Up With People. Other family features included a "Fun Fair Village," a "Country Western Fair" and a historic look at baseball sponsored by Famous-Barr, KMOX Radio, and Schnuck's Markets. Stunt pilot Art Scholl was a hit during McDonnell-Douglas' daily air show. The 1985 Fair was also able to attract out-of-town corporate sponsors such as Chrysler Corporation, which hosted an Auto Fair.

To promote ecology and recycling, "Operation Brightside" collected empty aluminum beverage cans at vendor booths on each day of the event. It was estimated that 98% of all cans sold were recycled. "A cooperative citizenry obeyed the city ordinance and didn't bring glass bottles or alcoholic beverages to the fair." Few arrests were made, and those only for disturbance of the peace. [57]

|

| Crowds watch the McDonnell-Douglas Air Show, 1985 VP Fair. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

The park was honored to have Secretary of the Interior Donald Hodel attend the last day of the fair with his wife. The secretary introduced Up With People, preceding the Grand Finale, a spectacular fireworks show which closed the fair. [58]

Executive Director Charles Wallace estimated a profit of $300,000 for the 1985 fair, "almost equal to its total profit during the first four years.

"The reason, he said, is the families.

"'Not only are the people not bringing their own alcohol, but they have their kids — and you know how kids are tugging on your leg wanting things,' Wallace said. 'We used to sell three beers for every soda, and this year it's 1 to 1. And the beer sales aren't down.'

"Wallace said the $300,000 profit would allow the VP Fair Foundation to reduce its debt of about $400,000 for commitments to the city for riverfront improvements. . . The foundation's surpluses must be spent on community projects or on future fairs." [59]

Superintendent Schober agreed to sign a special use permit for four more VP Fairs, with the understanding that the fair would be cut from four days to three, and that the Park Service would no longer fund the extra rangers on the special event teams.

SCHOBER SAID he asked Congress this year for the roughly $130,000 needed to pay for the 40 extra rangers, who help local police and fair security guards control the huge crowds. The money was classified as an emergency expenditure for law enforcement, he said.

"I've been able to justify it by saying that the fair is something we don't put on and something that might not be here in a given year," Schober said. "We used the emergency [law enforcement] funds on that basis. And I put it in my budget request again this year, but Congress didn't grant it. That means we must find alternative funding." [60]

This funding was covered by the VP Fair Foundation in subsequent years.

1986

As more than 200,000 expectant fans awaited the arrival of Dolly Parton on the main stage Saturday, July 5, they paid little attention to a security truck slowly motoring through the reluctantly parting masses. As the truck entered the maintenance tunnel, Ms. Parton, crouching in the back of the vehicle, was able to come out of her uncomfortable position. Moments later, after being successfully spirited onto the grounds, she appeared on the main stage to a tremendous ovation.

The 1986 fair, attended by more than three million people, broke all previous records for food and beverage sales. Hundreds of attractions on the grounds included Disney characters, charity fund-raising concerts by Ben Vereen and Lola Falana, a "Caribbean Carnival" sponsored by the Urban League of Metropolitan St. Louis, performing arts sponsored by the St. Louis Arts & Education Council, and a fun-filled "Children's Village." Trans World Airlines sponsored an "International Village," featuring dozens of ethnic groups and exotic foods. Every event, theme area and entertainment program was subsidized by a major corporation. [61]

|

| Crowds wait for a featured performer on the main stage at the VP Fair. Photo by John Weddle. |

The fair was once again planned as a family event, and minimal damage was inflicted on the Arch grounds. Well-coordinated cleanup crews handled 316 tons of trash, completing their task between 1 a.m. Monday morning and sunset of that same day. A park visitor from New Jersey was amazed at the swift pace of the cleanup crew. [62]

The fair was marred only by roving gangs of teenagers who preyed upon people as they returned to their cars after each evening's fireworks display. "The majority of the crimes were strong-arm robberies of individuals with gold chains or purses. . . A report Sunday night said a group of 100 youths had randomly assaulted fairgoers along Leonor K. Sullivan Boulevard and had been broken up by three club-swinging police officers." [63]

A police officer shot and wounded a youth about 10:50 p.m. Saturday when the youth pulled a tear-gas gun from his pants and pointed it at [the] officer. . . . Police were trying to break up a fight at the time, and most of those who were involved fled when the shots were fired. . . .

On Friday night, a bystander was shot in the leg during another scuffle. Another man also was reported to have been shot, but police said they had not found him. . . They said groups of young people ranging in age from 12 to their early 20s and ranging in size from five people to 40 people, had moved through the crowds, stealing gold chains, purses and other valuables from fairgoers.

"It's nauseating," said an officer . . . "We're not able to protect these people, that's the bottom line."

Another officer said, "It's going to kill this fair." [64]

Spokespersons for the fair minimized the effect of the crime, and when seen in a larger perspective, the success of the 1986 fair far outweighed these incidents. Based on the fact that the majority of these crimes were perpetrated by black youths from East St. Louis, the St. Louis Police Department asked the State Legislature to pass a bill permitting the addition of police officers from other departments in Missouri and Illinois to the VP Fair security force. They also asked that Eads Bridge, the only pedestrian access to the fair from East St. Louis, be closed between the hours of 3 p.m. and 4 a.m. [65]

1987

The closing of Eads Bridge in an effort to discourage gangs from crossing the Mississippi to repeat the harassment of the 1986 VP Fair was roundly criticized by the overwhelmingly African-American population of East St. Louis. Facing a charge of racism in a suit filed by the East St. Louis chapter of the NAACP, U.S. District Judge John F. Nangle ordered the bridge reopened after just one day. It was alleged that the bridge closing violated the right of people to travel and discriminated against them on the basis of race. [66]

Advance planning for the 1987 VP Fair culminated in the donation of $90,000 to cover special event team participation, and hotel accommodations and air travel were donated at no cost to the park. Plans and budgets were prepared requesting $25,000 in assistance under the Emergency Law and Order Fund to provide an advance special event team to complement JEFF staff for the setup and hosting of a three-hour ABC nationwide television special, in addition to ABC-TV's Good Morning America program, both featuring Barbara Bush, then the wife of the Vice President. Planning guidelines were prepared by the park and given to the City of St. Louis and the VP Fair Foundation six months before the event. [67]

The 1987 VP Fair was a three-day event with the theme "We, The People," honoring the bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution. Former Chief Justice of the United States Warren E. Burger served as honorary chairman. A special "Constitutional Village," sponsored by the Bar Association of Metropolitan St. Louis and St. Louis County, was established within the fairgrounds.

The fair opened with the conclusion of the first-ever U.S. National Senior Olympics, a week-long event which included 2,500 athletes aged 55 and older. Bob Hope hosted the closing ceremonies of the Senior Olympics and the opening ceremonies of the VP Fair. Hope and his wife Dolores also served as grand marshals of the VP Parade.

The ABC-TV special, "A Star-Spangled Celebration," brought national recognition to St. Louis, the VP Fair, the Gateway Arch, and the National Park Service. The three-hour "show of stars" was videotaped Friday evening, July 3, and telecast July 4 to millions of TV viewers. This prime-time special also promoted literacy in America. Project Literacy's national spokesperson, Barbara Bush, appeared. Entertainers included Tony Bennett, Suzanne Somers, Bernadette Peters, Chubby Checker, Natalie Cole, Peter Allen and the Rockettes. [68] Robert Urich and Oprah Winfrey co-hosted the show. Good Morning America broadcast live from the Arch on July 3. Despite the positive publicity represented by the ABC special, the VP Fair Foundation ended up paying for the major portion of the costs. This special, more than any other single factor, threw them into debt. [69]

Wind and torrential rains throughout the three-day fair dampened everything but the spirits of all involved, from the park staff (including seven regional special event teams and a contingent from the U.S. Park Police), to the estimated 2.5 million people who attended. In addition to their other woes, the VP Fair Foundation carried no rain insurance. [70]

Damage to the grounds was extensive, and an estimated $60,000 in lost revenue was suffered each day of the event due to the rain. Another $120,000 was spent in merely keeping the fair going, putting tents back up, covering muddy areas with plywood, and pumping out water. Complaints from the public were numerous. [71] Serious consideration was again given to an alternative site for the fair, and a VP Fair Foundation committee investigated the possibilities. They concluded that the fair "was now so grandiose that it could only be produced at the Gateway Arch." [72] Superintendent Schober noted, however, that the permit for the VP Fair expired after 1988, and said that "it was time to review the impact on the national park and whether anything could be done to ameliorate it." [73]

1988

"Parks U.S.A." was the theme of the 1988 fair, which provided a perfect opportunity for the National Park Service to erect, for the first time, an exhibit of its own. The three tents in the NPS area were staffed by park rangers from JEFF and from other parks across the country. Harpers Ferry Center provided an exhibit on the National Park System. Visitors also encountered an information tent about NPS areas, and the presentation of a continuous schedule of interpretive programs. Approximately 38,000 visitors were contacted at the booth. [74]

Advance planning for the 1988 VP Fair culminated in the donation of $85,000 to cover National Park Service participation. Hotel accommodations and air travel were donated.

For the second consecutive year, ABC-TV produced a two-hour nationally televised, prime-time special, hosted by Patrick Duffy and Joanna Kerns, and featuring Glen Campbell, John Hartford, Kool and the Gang, Leroy Reems, Restless Heart, Judy Tenuta, Michael Winslow and Pia Zadora. Good Morning America once again broadcast live from the grounds of the Gateway Arch. [75] Both presentations featured Barbara Bush. Then Vice-President George Bush attended the celebration as well, hosting a reception for citizens naturalized at the fair, and speaking to the crowd. Security was increased for Bush as friction with Iran had been growing since the downing of an Iranian airliner by a U.S. Navy ship in the Persian Gulf. [76]

Director of the National Park Service William Penn Mott was the honorary chairman of the fair and rode in the opening parade, which featured an NPS float with all types of uniformed Arch employees and volunteers represented. [77] Mott said that he was not distressed by the damage to the grounds caused by the crowds. "'Parks are for people,' he said. 'We are not dealing with a natural resource here. We've got the technicians and the knowledge to put it back together again. I don't think it's a problem for us.'" [78]

Performers were set up on the Overlook Stage, at the foot of the Grand Staircase on the east side of Leonor K. Sullivan Boulevard. By holding the main events on this riverside stage rather than under the Arch, the grounds were spared a great deal of wear and tear. A 20-by-30-foot video screen was set up near the north leg of the Arch so that fairgoers could watch the entertainment live. The one drawback to this plan was that fewer people could attend events. While 200,000 could assemble in front of the stage on the Arch grounds, only 25,000 could be comfortably seated on the steps to the levee. [79]

Monsanto Corporation sponsored the VP Fair's popular "Family Village" and Kodak sponsored an "All-American Balloonfest." The former Presidential yacht Sequoia sailed to St. Louis for the event, and was toured by more than 26,000 people. Two events which continued beyond 1988 were introduced, "Senior's Day" and the "Pioneer Craft Village," sponsored by Pet, Incorporated, which included a pioneer log cabin replete with woodworkers, weavers, and other artisans. [80] "Fairgoers were delighted with the fair's new look. More education exhibits were added . . . " Crowds were well-behaved due to the cooler weather. Families were impressed with the change. "'It seems like more of a family thing than just a grown-up thing'" said one fairgoer. Puppet shows, diaper-changing services and fingerprinting for child identification were also cited as evidence of the changed nature of the fair. [81] In addition, the fair was singled out for its sensitivity to the needs of disabled visitors. [82]

An estimated 2.68 million people attended the event, which produced some interesting statistics. More than 120,000 bratwurst and hot dogs, 300,000 soft drinks and 300,000 cups of beer were sold at the 1988 VP Fair. In addition, 1.7 million pounds of ice, 30,000 pounds of charcoal and 850 gallons of barbecue sauce were consumed. The tally also included 50,000 rolls of toilet paper used in the hundreds of portable toilets. The event produced more than 150 tons of trash. [83]

An awareness of the possibly prejudicial practices of past fairs was brought to the surface when the Eads Bridge was closed in 1987. As a result, fifteen black community and business leaders were appointed to the board and various committees of the VP Fair Foundation in 1988. Chris Mullen, "a black woman who has experience booking entertainment . . . [was appointed] to a three-year term on the fair's entertainment task force. The Rev. Samuel Hylton, president of the St. Louis Clergy Coalition, was one of seven prominent African-Americans appointed to the board of directors, which totaled 62 members. These were the first black members in the 110-year history of the Veiled Prophet." [84]

"'I feel my appointment and the other appointments really represent a beginning,' Hylton said. 'You have to make certain that the black community is represented in the structure of the VP Fair on all levels.

"'I think the black community is a rich resource. We are ready to pull our load if we are convinced the efforts are sincere and authentic.'" [85]

An editorial in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch summarized the African-American point of view:

The VP Foundation's promise to remedy the absence of blacks from its executive body and from many fair activities marks a good first step toward improving the image of its Independence Day event. The foundation has pledged to begin an ad campaign to boost black attendance at the fair and set up a permanent committee to help assure black participation.

The proposed changes are welcome, even if they are overdue. It's no exaggeration to say the lily-white legacy out of which the fair grew has remained disturbing to many blacks. The onus for bridging this racial chasm had to be on fair organizers, and they have made a good start by abandoning the outdated notion that all they needed to attract blacks was to give them some stage time for gospel music.

A wider range of entertainment would help, but this by itself wouldn't generate exceptional black interest. The VP Foundation now realizes the first thing it has to do is make clear that black attendance is encouraged. That, presumably, is also what has been behind suggestions over the years of giving the VP Fair a different name. This change would make a symbolic break with the past and would show even more that the organizers are truly concerned about broadening the event's appeal. [86]

The foundation's agreement to reach out to blacks should help ease the memory of last year's sneak closing of the Eads Bridge to East St. Louis pedestrian traffic. More than any other incident, that action conveyed a feeling of hostility toward blacks — an attitude unfortunately furthered by paternalistic comments from some VP officials. Now, the proposed efforts to boost black participation show that the foundation realizes that everyone benefits from making the fair a genuine communitywide celebration. [87]

1989

The 1989 VP Fair, attended by an estimated 3 million people, lasted for four days and was based around the theme "Education is America's Future." The NPS sponsored an exhibit tent, information tent, and shared a program tent with the St. Louis County Parks. Interpretive programs were given to an estimated 20,000 people. Three special event teams were brought in from National Park Service areas across the country, and 25 off-duty St. Louis police officers provided security for the event. The VP Foundation provided $85,000 to cover NPS maintenance and law enforcement costs, and the City of St. Louis provided an additional 600 police and fire personnel. Financial difficulties facing the VP Fair Foundation necessitated the requirement of more stringent financial and programmatic control for 1989 than for any of the eight previous fairs. The VP Fair Foundation paid the remainder of the costs for 1988, totaling $24,000 plus $700 interest, and all of the expected costs for 1989 prior to the permit being issued. A signed contract was required for replacing trees, and providing for an immediate 3,000 yards of sod, with an option on an additional 3,000 yards if needed. [88]

The 1989 fair was the first to be broadcast to audiences worldwide over the Voice of America Radio Network. Twelve Voice of America reporters, fluent in eight languages, interviewed fairgoers and described the events.

July 3 was "Education Day," which featured seven themed "study halls" in what was billed as "America's Largest Classroom." Each of the study halls challenged fairgoers with games, puzzles and other lessons which made learning fun. Counseling was provided for high school students. A "Living History Village," a logging camp, a giant globe and an education stage also highlighted the event. [89]

A massive naturalization ceremony was conducted on July 3, as 150 people gathered at the South Overlook. These immigrants, representing 54 countries, simultaneously took the oath of allegiance and generated international publicity for the park and the event.

1990

Advance planning for the 1990 Veiled Prophet Fair resulted in a safe and well-attended event with an estimated 2 million people over four days. Four special event teams provided visitor and resource protection. The Veiled Prophet organization covered NPS maintenance and law enforcement costs, and the City of St. Louis provided an additional 600 police and fire personnel. The fair was held on Saturday and Sunday, shut down on Monday, and resumed on Tuesday and Wednesday the 4th. [90]

The theme of the fair was "Education and Freedom Make America Strong," and features included a 19th-century logging camp, two actors from television's Sesame Street, a 900-pound, ten foot globe (used to teach geography), a one-room schoolhouse complete with quill pens, and "We Are the World," where visitors could sample crafts, activities and clothing from other cultures. Activities included making fortune cookies, trying out Adinkra printing from Ghana, performing radio plays, and obtaining passports. Reading was encouraged in an exhibit sponsored by the St. Louis Public Library and Pet, Inc. [91]

The international flavor of the fair was enhanced by fourteen students from South Africa and former "Iron Curtain" countries, who attended a discussion on the U.S. Constitution at the Old Courthouse, saw a Cardinals baseball game, and participated in a two-hour discussion on the fair's overlook stage about the changes in their homelands. The students were impressed by the beauty of the United States, and by the little things which Americans take for granted. A young woman from Estonia was touched by the nametag she was given. "It's so personal . . . I feel like a queen," she said. [92] A Japanese video crew shot scenes of the fair for a documentary on "the unique culture of America." [93] Dustin Nguyen, who fled Vietnam in a small boat in 1975, came to the fair as a well-known television actor from the program 21 Jump Street. Nguyen spoke of the impact which America's freedoms and educational opportunities have made on his life. [94]

Further international effects were provided by fireworks from fourteen countries which were presented over the four successive nights of the fair. One of the Japanese rockets, called the "chrysanthemum," was able to change colors four times. The fireworks were accompanied by music over the local radio stations, and preceded by a night air show on two of the evenings. [95]

|

| National Park Service information tent at the VP Fair, 1990; Chief of Museum Services and Interpretation Mark Engler speaks to the press. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Entertainment included Fairchild, Larry Gatlin and the Gatlin Brothers, Natalie Cole, Juice Newton, the Temptations and the Four Tops, the Grass Roots, Johnny Rivers and the New Riders of the Purple Sage. Corporate displays by Budweiser showcased racing cars and promoted sober driving, while the TWA exhibit included a Pratt and Whitney engine and airline food. [96]

Soaring temperatures kept numbers low, but family attendance highlighted an exceptionally well-behaved crowd. [97] Despite the success and changed nature of the fair, protest letters continued to appear in the local papers. Whenever crowds of two million people gather for four days in a limited area, there are bound to be problems; however, by 1990, positive feedback began to outweigh negative. [98]

|

| NPS cannon crew at the 1990 VP Fair. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

1991

The 1991 Veiled Prophet Fair was moved to the Labor Day weekend. Aside from enabling fairgoers to enjoy milder temperatures, it was thought that the Labor Day date would allow the completion of roof repairs to the underground visitor center complex, then in progress. [99]

During 1991, needed changes were initiated in conjunction with the City of St. Louis, and the VP Fair Foundation, to reduce the negative impact on natural and cultural resources and enhance protection for the estimated 2-3 million visitors to the Arch grounds. The 75th anniversary of the National Park Service was one of the highlights of the 1991 VP Fair. A servicewide 75th anniversary interpretive program was planned, coordinated and directed by JEFF. The success of this coordinated effort was insured by eight NPS regions, Harpers Ferry Center, and the United States Park Police, working together to bring the best NPS interpretive programs to St. Louis for the event. Deputy Director of the NPS Herbert Cables rode in the VP Parade, and lavish media attention highlighted the role of the National Park Service across the United States. Diverse programs featuring 40 interpreters representing 25 NPS sites, were well-received by the 26,000 visitors who stopped by the four NPS tents at the fair. [100]

The route of the VP Parade was altered due to the large amount of construction on downtown streets for "Metrolink," St. Louis' new mass transit subway system. The parade included three Macy's-style balloons. [101]

Entertainment included some of the biggest names in show business, with Mary Wilson (formerly of the Supremes), Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Huey Lewis and the News, Styx, Bill Cosby, Smokey Robinson and Kenny Rogers performing. [102]

A full range of services were available for the disabled. An article highlighted the experience of a St. Louis man at the 1990 VP Fair:

Duane Gruis went to the VP Fair last year and had no trouble getting around or seeing everything he wanted to see. He had such a good time, he's going back this year.

Gruis uses a wheelchair, and he is urging other would-be fairgoers who use wheelchairs to attend the fair, which begins Friday and runs through Monday on the grounds of the Gateway Arch.

"They'll have a good time," said Gruis, who is an independent-living specialist with Paraquad, Inc.

Gruis said that he did not attend the fair until last year.

"It wasn't hard to do. I knew where the reserved parking spaces were, and I got to the fairgrounds without any trouble. And I saw just about everything I wanted to see."

He said that the large number of concrete walkways had made it easy to get around in a wheelchair and that accessible restrooms had been in the disabled services tent.

The director of services for the disabled at the VP Fair was Bill Sheldon, who also worked for Paraquad. Sheldon held this post for every fair beginning with the first, in 1981. [103]

|

| Kenny Rogers was rained out at the 1991 VP Fair, but performed in 1992. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

The "Family Village" featured a "burning house" to teach kids how to exit a building during a fire, a "Safety Town" where children on tricycles were taught the rules of the road by real policemen, "Living in Other Lands," where children could talk with former Peace Corps volunteers, and "Mathorama," with a variety of math games. [104]

Sunday was declared "Senior's Day," dedicated to an awareness for the needs of seniors. Many appreciative letters appeared in the local press: [105]

All last week we read about controversy surrounding the VP Fair, but not much was said about the day provided for the elderly.

The ballroom of the Clarion Hotel was made available along with coffee, cookies, popcorn, punch . . . and a full day of entertainment.

All this was free. So, too, was the transportation to and from the Clarion Hotel via mini-buses, with very courteous and thoughtful drivers. [106]

Sudden, violent thunderstorms forced the early closing of the fair at 2:40 p.m. on Monday, the final day of the festivities. The fireworks finale and the performance of Kenny Rogers were canceled.

A controversial new system required that fairgoers buy scrip tickets to exchange for food, drinks and rides. Confusion was caused, since many vendors of crafts, products and services accepted cash and not scrip. Many fairgoers were angered by the fact that scrip sales were not refundable. Many bought scrip tickets just before the cancellation of the event on the final day. Some complained that the ticket system forced them to wait in line twice; once to buy a ticket, and again to use the ticket to obtain drinks or food. Nevertheless, VP Fair Executive Director Mel Loewenstein defended the scrip system, and said that it would continue to be used, with refinements, for future fairs. [107]

"Like the cartoon character whose problems hovered overhead wherever he went, the VP Fair can't escape its twin nemeses, controversy and bad weather. Though the fair moved to Labor Day this year from its traditional July 4th spot, the equally traditional heat and humidity followed along . . . " [108] It was decided to return the fair to its original July Fourth weekend in 1992, because JEFF's division chiefs agreed that there was virtually no difference in the results, and that the July date was actually better for the repair of the landscape. [109]

By 1991, even the skeptical Riverfront Times editorialized: "You have to hand it to the people running the VP Fair. Not only have they answered their critics (finally) by no longer accepting public monies to fund their activities, they've also taken seriously the plea to get minorities involved, and added legitimate attractions, including amusement rides, participation games and significant exhibitions." [110]

The VP Fair and Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

Every division of JEFF must put their best efforts into each year's VP Fair. A lot of hard work and time go into the planning, implementation, protection, and cleanup for each of these events. [111]

Superintendent Jerry Schober, reviewing a decade's worth of VP Fairs, reflected:

|

| Bill Cosby performed at the 1991 VP Fair. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

[The VP Fair] put us in connection with some of the largest corporate heads in this town. You got there first, you let them see how you manage and they could acquire respect for you. One time it came down the pipeline that one corporate president said, "I had not had anybody tell me no in fifteen years. And that sucker [Schober], I was not with him for an hour before he told me no three times . . . [But] I think I know where he is coming from and, damn it, he's working for me and so I can take it." I think we earned a lot of respect for the job that we do, for the entire Park Service. And it has enhanced us.

For instance, we got a half million dollar Indian Peace Medal collection that we would never have received if we hadn't struck up a relationship with one of those individuals. [112] We can get support from them from time to time. But it's involving them and working with them, not just working by ourselves.

It has been very costly. . . . If we had all the money in the world, we probably would not put on the VP Fair here. But, since we are putting one on, and if they are going to do it right, we're not going to backstab them or short-circuit [it]. We want it to be the best VP Fair ever put on. So that's how we look at it each time. We don't work counterproductively. [113]

|

| The grounds of the Gateway Arch during the 1990 VP Fair. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Hosting the VP Fair had many drawbacks during the 1980s. It took time for the park and the VP Fair Foundation to work out problems involving destructive use of the grounds, prompt payment for repairs, the improved representation of African-Americans, and their own financial difficulties.

But the fair had many benefits as well. It served as a showcase for local business, and a contact between the park and corporate heads. The gifts bestowed upon the city from its profits were important, as was the international publicity and goodwill it generated for the city. The VP Fair was also important because it became a part of the warp and woof of life in St. Louis. Since Jefferson National Expansion Memorial was partially created with funds obtained from the city of St. Louis, the park remained a place which belonged to the people of the city as well as the people of the entire United States. The annual VP Fair was a time when the people of St. Louis could enjoy their park in a unique fashion. Few National Park Service areas could claim such a close identification with their community, both as a regional symbol and sight-seeing attraction, and as an integral component in their city's largest annual celebration.

|

| Crowds line the riverfront at the 1989 VP Fair. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

jeff/adhi/chap3-2.htm

Last Updated: 15-Jan-2004