|

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

Administrative History |

|

|

Administrative History Bob Moore |

CHAPTER FOUR:

Maintenance

Although most of the major development of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (JEFF) was complete by 1980, the business of maintaining the park was just beginning. Basic operations and approaches to the management of the site were implemented for the first time during the 1970s, and a number of projects during the 1980s were carried out to correct park problems and to improve operations in the maintenance division. Maintenance work tended to fall into one of four primary categories: building services, grounds, transportation system, and custodial. This chapter is divided into four sections in order to fully describe each facet of the JEFF maintenance division in detail.

Part I: Building Services and HVAC

Maintenance Management System

Computerization in the Maintenance Division grew during 1985. Considerable expansion was needed for the Vista Personal Computer in the Facility Manager's office to incorporate the new Maintenance Management System (MMS), a computerized information database which set up schedules of cyclic maintenance and kept records of work performed. [1]

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and Indiana Dunes served as pilot parks for the MMS in the Midwest Region, and implementation began in May 1987. The process was handled expediently by the reassignment of Building Services, Heating and Air Conditioning (HVAC) foreman John Patterson to the position of MMS coordinator. Because JEFF was one of the first National Park Service areas to implement MMS, the initial processes were sometimes crude, but the learning experience was invaluable. Enhancements to the system continued to make it a more useable tool, and an employee was soon needed to handle data entry and to maintain the system. [2]

With the arrival of Laura Rummle, hired as MMS coordinator in 1990, goals and objectives were set which were essential to the continuing success of the MMS System at JEFF and at other parks. Over a six-month period in 1990, JEFF maintenance supervisors received hands-on experience with computer hardware and software. This process was continued with work leaders and other staff members. Monthly MMS meetings were instituted with the MMS coordinator and supervisors, to exchange information and data and to review the overall program. The JEFF coordinator worked closely with the Regional MMS coordinator in assisting other parks, and on special projects. [3]

Heating and Air Conditioning

Maintaining the complex heating and air conditioning units at JEFF was the responsibility of the HVAC division. The HVAC system provided a comfortable environment for visitors and employees within the Gateway Arch complex, including the underground, 42,912-square-foot Museum of Westward Expansion; the observation deck at the top of the 630-foot-tall Gateway Arch; and throughout the facility's support rooms and tunnels. Air conditioning in the form of window units was also added to the Old Courthouse's exhibit galleries and second floor offices. The HVAC crew continually searched for methods to improve the efficiency of the operation, especially in the area of energy management and conservation. [4]

|

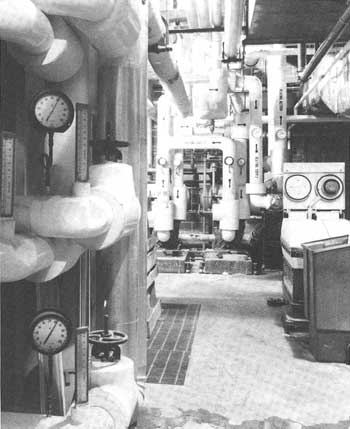

| Interior of the HVAC equipment room in the Gateway Arch complex. NPS photo by Kris Illenberger. |

Between 1979 and 1980, a 600-ton air conditioning unit in the Gateway Arch complex was replaced, at the suggestion of John Patterson, by two 300-pound units. Mr. Patterson based his decision on the fact that the enormous 600-pound unit was running on the "low end" of its capacity. [5]

With a view toward improving operations, the park let a contract for the installation of an Energy Management System (EMS) which monitored the use of energy at JEFF and provided information toward the development of more efficient ways of managing it. On October 6, 1983, Mack Electric Company's bid of $62,997 for the EMS was accepted. This included all of the computer software and hardware, operator input/output devices, field processing units, automation sensors and controls, wiring and piping. By February 1985, the system was in place and operating. [6] Improvements were immediately initiated which allowed automatic control of the chiller and some of the air handlers. [7]

As an additional phase of implementing the EMS, a 1985 contract was awarded to Akbar Electric Services Company to provide all tools, materials, staffing, and programming to convert the chiller control and monitoring system to full automation. By March 30, 1986, this project was completed for a total cost of $43,101. [8]

Improvements to and additional expansion of the Energy Management System continued in 1985, and while the significant cost reductions of the initial period of operation could not subsequently be matched, control and consistency were maintained. [9] Wiring was completed in 1986. While the EMS did not at first result in meeting the required NPS cost reductions, a working knowledge of the system increased steadily. [10]

Emergency funding from the Midwest Regional Office (MWR) was requested in 1986 when a breakdown in the Trane Air Conditioning chiller occurred. [11] The problem was corrected at a cost of $30,000, under a contract which represented a major effort by the MWR Procurement Division and the park staff. [12]

Chillwater steam controls for five air-handling units were installed in 1988, and the main supply shut-off valve for potable water at the Arch was replaced. The installation of wiring and valves, and the modification of the software program for EMS control of the cooling and heating valves for the top of the Gateway Arch were accomplished in 1989. Adjustments by the operating staff made the computerized control system more efficient, as an alarm system was installed to alert the operators to failures in critical cooling or condenser water circuits. [13]

Major routine and preventive maintenance was performed on the cooling tower and condenser pump systems in the Arch complex during 1989. The fan wheel sections and line bearings were replaced; water was re-routed through disbursing piping; eliminator sections were dismantled, cleaned and repaired, as were pumps; and check valves were rebuilt. An electronic water level control system was purchased and installed in the Arch cooling tower, which reduced the amount of water and chemical treatment used. [14]

The HVAC division rendered assistance to Hellmuth, Obata, & Kassabaum (HOK), an architectural firm located in St. Louis, in preparing a bidding package for installation of a new air handling unit to serve the expanded Gateway Arch Museum Shop. At the end of 1990, HOK performed a final check on the design, and analyzed chilled water system flow demands. Installation was made before the summer of 1991 by Quality Heating and Air Conditioning of St. Louis. [15] An annual inspection in 1990 revealed the need for an overhaul of Air Handler Unit #10 in the Gateway Arch complex, and HVAC rebuilt the motor, brackets, bearings and coils. [16]

The pneumatic control air supply was improved in 1991 by moving and installing two compressors in the south mechanical room to serve the south side of the Gateway Arch complex and museum. The back flow preventers for outside drinking fountains, the inside display fountain, and the chilled water make-up supply line were also rebuilt. Mixed-air dampers outside and pre-heaters on the north and south leg air handling units were replaced. These units supplied conditioned air to the observation deck at the top of the Arch. [17]

Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site

In addition to other tasks, the JEFF building services crew assisted the new NPS site in St. Louis County dedicated to Ulysses S. Grant by performing several maintenance tasks. Two new furnaces were installed in the historic house, which necessitated the modification of adjacent duct work. Several days of work were performed on the roof of the house, to stop major water leaks. Missing shingles were replaced to provide some measure of safety from water damage. A new electrical system was installed, with the most hazardous electrical problems removed and/or disconnected. [18]

Cyclic Maintenance

An extensive program of cyclic and preventative maintenance was performed by the HVAC staff to keep the Gateway Arch systems up and running. Every three years, pumps for the water circulation in the AC units were overhauled, and filters were changed regularly. Frequent pH tests performed on the water in the park's cooling towers kept rust and algae to a minimum. Steam traps and strainers for the heating system were taken apart every other year. Each morning, a two-hour walk-around inspection circuit was made of the entire AC system in the Arch complex. Ordinary items which deteriorated due to normal wear and tear, such as faucet valves, were replaced every four years. Doors in the Arch complex lasted an average of eight years before they needed replacement. [19]

|

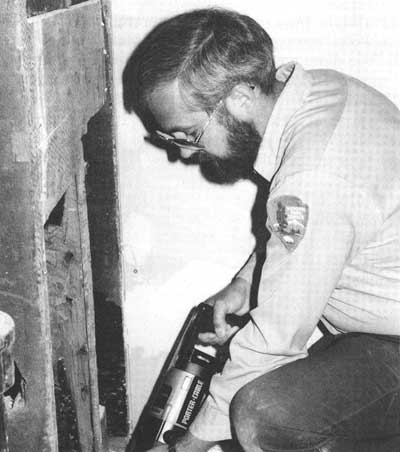

| Maintenance Mechanic Lonnie Collins assisting in the construction of an accessible restroom at Ulysses S. Grant, one of many maintenence tasks handled by the HVAC crew. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Old Courthouse Repairs

The building services division rewired the entire electrical system of the Old Courthouse during 1981, from the basement up to the 5th level, completing the project on June 8. Old wiring was stripped out and replaced, and new distribution panels were installed. [20]

Four new exhibit galleries were created on the first floor of the Old Courthouse in 1986. Offices and partitions were removed, walls were patched, replastered, and painted, and window frames were repaired. Exhibit bases were built for the new displays, and carpeting installed. The dioramas built under the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the 1930s were moved and rearranged. A projection booth and a bookstore for the Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association (JNEHA) were also constructed. All of these projects were accomplished by a crew of eight JEFF employees, in conjunction with their regular duties, in 1986. Window air conditioning units for the four new exhibit galleries on the first floor of the Old Courthouse were installed in 1987 and 1988. [21]

The administrative office space in the south wing of the Old Courthouse was remodeled during 1986, resulting in more efficient utilization of space. Lighting for the east and west stairways between the inner and outer dome of the rotunda was also installed. The first and second floors of the building were repainted in preparation for hanging the Arts in the Parks exhibit. [22]

The brick sidewalk around the Old Courthouse was re-tuckpointed in 1987 as part of a cyclic maintenance project. The job turned out to be much more time-consuming than expected, and Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) workers were used to supplement the maintenance staff. Considerable pressure was brought to bear on the park by local unions, who objected to the use of YCC workers on the project. Several inquiries were made by union locals, who made contacts with local congressmen on the issue. The unions relaxed their pressure when they realized that taking jobs away from youths on a special summer program would not improve their image. [23]

Emergency funding was received for $100,000 worth of storm damage caused in January 1991 by falling ice, which dented the Old Courthouse roof and shattered second floor skylights. A contract for repair and replacement of the skylights was completed with a minority architectural/engineering (A/E) firm, Kennedy and Associates of St. Louis. Construction was performed by another minority contractor, Innovative Systems, Inc., of Kansas City, Kansas, and completed by the end of May 1992, allowing for a return to normal visitor traffic patterns to the third and fourth levels of the Old Courthouse. [24]

Physical Improvements and Preventative Maintenance

Maintenance employees in building services contributed an incredible amount of miscellaneous construction and repair projects throughout the park between 1980 and 1991.

|

| Skylight damage, Old Courthouse, 1991. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

These projects included the installation of new stainless steel handrails to replace painted units in the upper load zones of the Gateway Arch; the installation of a new telephone system in 1987, which required the placement of considerable conduit ductwork; informational signs positioned on the Arch grounds; updating of accessible restroom facilities; and the repainting of the columns in the Museum of Westward Expansion. [25]

Major remodeling of the ticket area run by the Bi-State Development Agency at the Gateway Arch was completed in 1989, providing for more efficient park fee collection activities, which were implemented during that year. [26] The rehab included a fee collection facility, offices, storage, money counting stations, security, a new queuing system and signs. The space was enlarged to 1,800 square feet, and could not be serviced by the existing HVAC systems. This required the installation of a separate heating and cooling unit, both for the comfort of the staff and for the proper care of the computerized ticketing and reservation system. The remodeling was designed Hellmuth, Obata, & Kassabaum, and construction was jointly completed by a local contractor and the park building services staff. The park staff installed an overhead sprinkler system, all of the electrical wiring for lighting and power, computer wiring, a security system, and telephones. [27]

|

| Signs fabricated by the St. Louis Ornamental Stone Manufacturing Company, 1986. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

A mud jacking program was implemented in 1989 to correct the most serious stumbling hazards on the Arch grounds walkways. In the process of mud jacking, a hole is drilled into concrete or stone paving slabs which have become uneven through settling. Mortar is poured into the hole, which when dry firmly supports the slabs from below and evens them out in relation to neighboring slabs. When slabs become cracked they are broken up and replaced. Approximately 15 slabs were adjusted, and in conjunction with this project, 150' of redwood expansion strips (which separate the concrete slabs on the Arch grounds) were replaced. [28]

One half of the grating on the Gateway Arch entrance ramps and four fresh air intake grates were replaced during 1989. The grating over the cooling towers was sandblasted and repainted through the cyclic program.

In 1989, the park replaced the 13-year-old carpeting in the Museum of Westward Expansion. Problems with the contractor regarding material specifications and installation resulted in time-consuming administration and supervision of this project. More than 60,000 yards of carpet were installed, which developed a fuzzing and piling almost immediately. The contract was terminated and a settlement reached with the contractor. The next replacement contract specified that the color of the carpet be modified to allow for more competitive bidding. In 1990, new carpet and installation services were donated to JEFF by Allied Fibers, a division of Allied Signal Corporation, in celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Gateway Arch. [29]

A temporary 300-amp, 480-volt power supply for the 70mm theater site was designed and installed in 1990. Existing supply panels were modified to provide the necessary power to run excavation and construction equipment for the project.

Eighteen bollards (movable post-like barriers, similar to stanchions but wider and heavier) were installed at six locations along the walkways of the Gateway Arch grounds for traffic routing and control during large events such as the VP Fair. The bollards were fabricated by Westerheide Sheet Metal of East St. Louis, and installed by park staff in core-bored 18-inch diameter holes cut and formed by Concrete Cutting Services, Inc., of St. Louis. [30]

Plans were prepared by Denver Service Center to repair the badly deteriorated stairs of the south overlook. A ramp of steel-plate material salvaged from informational signs and square steel tubing was constructed on the stairs by the HVAC staff. In order to better utilize storage space inside the south overlook structure, a contract was made to cut a larger opening through the block wall and install a rolling steel overhead garage door with an electric motor. This modification allowed grounds vehicles to enter the storage space below the observation deck. Completion of this work, in 1991, included a gate at the top of the ramp and an exterior key switch to operate it. The deteriorated stairs to the overlook were overlaid with a two-inch topping of concrete by park staff, and the overlook was reopened to the public. It was anticipated that these repairs would provide an additional five to eight years of use before total replacement was required. [31]

These brief examples give an indication of the amount of time and money saved by JEFF through having talented employees on staff, able to complete or supervise the completion of a wide variety of complex maintenance tasks.

Entrance Ramps

By 1983, the north and south terrazzo entrance ramps to the underground visitor center were badly deteriorated. On November 17, the National Park Service advertised in the Commerce Business Daily for professional A/E services relating to the replacement of the ramps. Title I services included problem analysis and the presentation of alternative remedial solutions. Title II services consisted of the preparation of construction documents. Under Title III services the contractor provided assistance to the government during the contract bidding and construction phases of the project. [32]

On January 26, 1984, WVP Corporation and R.L. Praprotnik and Associates were selected to submit unpriced technical proposals for the described A/E services. WVP was selected for Title I and II services on April 30, 1984. As outlined in the Scope of Work, the contractor determined the causes of the deterioration and proposed solutions, complete with preliminary design drawings and cost estimates. A further component of the project was the investigation of the installation an ice/snow melt system utilizing either electricity or available waste heat. [33]

On September 26, 1984, a $516,220 contract for constructing the ramps was awarded to Ed Jefferson Contracting Company. The existing terrazzo surfaces were replaced with granite surface blocks, and the ramps were waterproofed. This last task proved to be troublesome, for soon after completion of the job water was discovered to be seeping under the stone. On June 25, 1985, JEFF Facility Manager Bob Kelly, the authorized contract representative, sent a letter to Ed Jefferson Contracting pointing out the water problems, noting that several of the granite stones were cracked, and that the caulking had failed to bond. He did not receive a response. Kelly then asked WVP Corporation, as the contractor with the responsibility for supervising the work, for an explanation. WVP contacted Ed Jefferson Contracting, who, in turn, looked to the stone work subcontractor, John Klaric and Milligan Stone Contracting. Klaric claimed that it had nothing to do with the stones or the manner in which they were installed. They claimed that the problem was unavoidable due to the large amounts of water that ran down the legs of the Arch during heavy rains. Rejecting this explanation, Kelly appealed to the NPS Midwest Regional Contracting Officer, who subsequently notified Ed Jefferson Contracting that, under the terms of the contract, they were responsible for correcting the problem. [34] The standard grout was replaced with urethane caulking, a project which fell to the building services staff. [35] A new gray granite surface was applied to the entrance ramps in December 1985. The appearance of the ramps was improved, and the new anti-icing heat mats functioned well. [36]

Water Intrusion

Water intrusion was an ongoing problem at the Gateway Arch visitor center from the time of its creation in the mid-1960s. Leaks in the ceiling were repaired in 1967. Major floods in 1981 overwhelmed the facility's pumping stations. [37] An underground structure with a flat roof, by 1987 the 20-year-old visitor center had begun to leak in several places, causing major concerns. Preliminary inspections by Michael Fees of the Midwest Regional Office, and Bob Whissen of the Denver Service Center, provided expertise and technical support for the project. [38] In 1987, a contract for A/E services was awarded to Zurheide-Hermann, Inc.. The project called for a field investigation to determine the source of the water intrusion and a technical report to examine, evaluate, and propose remedies. The results of this report formed the basis for construction documents, including complete and accurate drawings, specifications, and cost estimates for repair. [39]

|

| The roof of the underground visitor center/museum exposed for repair, 1990, as seen from the top of the Gateway Arch. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

While the A/E contractor was digging test wells in conjunction with the water intrusion study, their drill rig penetrated the main electrical underground service line to the Arch. This mistake cost the contractor in excess of $20,000 to repair. A claim was made by the contractor to the NPS Contracting Officer for reimbursement, which was denied. A new scope of work statement and task directive were issued to Zurheide-Hermann in 1988, which expanded the project to include correcting the run-off water problem around the Arch complex, as a result of flooding which took place in July 1987. [40]

One of the results of the water intrusion investigation was the discovery of several cracks in the ceiling support beams, and the possible lateral movement of some of the beams and roof slabs. This caused great concern and prompted further inspections. [41] For two summers (1989 and 1990), visitors, especially during the Veiled Prophet Fairs, were not allowed on the grounds area over the visitor center roof, which was fenced off. In 1990, the scope of the project was again expanded to include not only waterproofing the roof and removing asbestos, but erecting structural reinforcements which would allow loading the surface above the roof to its intended design capacity of 100 pounds per square foot. [42] Jerry Schober recalled:

The as-built . . . drawings, were not correct because we found that where there were supposed to be beams with stirrups, that they were not put in that way. We found . . . cracks in some of them that, I bet you, were there when they installed them. And we also found out our load limit was more restrictive than we had earlier thought. I thought at one time I would not have a VP Fair but two years because I called the Denver Service Center and asked them to tell me how much my roof would withstand under heavy rain and thousands of people. To my chagrin they said, "Schober, the only way you could overload that roof would be by stacking the people like a pyramid." Well, since we had to go back in and look at the water problem, we found out the roof would hold a lot less weight, and because of that we had to come back in and totally recover the roof with a new light-weight material. [43]

On site work began in July 1990 with Zurheide-Hermann serving as the designer and Kozeny-Wagner, Inc., of Arnold, Missouri, as the contractor. As a first step, all soil was removed from the roof of the visitor center and museum, a two-acre area. The soil was hauled from the site and recycled for use elsewhere. Such large amounts of soil could not be stored within the limited boundaries of the park, and the soil was of poor quality. [44] The next step was the installation of Pave-Prep, a waterproofing membrane. In an effort to lighten the structural load to less than 100 pounds per square foot, it was decided to use an Elastizell lightweight cement fill instead of replacing the earth backfill. Modifications to the contract resulted in an increase in price by 11%, to more than $1.5 million. [45]

Heavy rains soon revealed that the waterproofing material, "a sheet composite of a lower asphalt-impregnated fabric with a nylon mesh upper reinforcement, had been damaged by the small, skid-steer loader used to distribute materials to the installers." As a result, the roof leaked once more. [46] The manufacturer/installer agreed to replace the product, and the waterproofing was again removed down to the bare roof. The application was begun anew, this time without traffic. When complete, the roof was divided into six sections for a flood test of the new material. Each area was flooded with two inches of water, proving its integrity.

Attention now turned to the questionable strength of significant beams, running the length of the museum, east to west on both sides. All the various ceiling systems framed into these beams, and they had cracked due to relative movements between them. Structures need to allow for movement, for if it is restrained, concrete will crack. The cracks identified in the underground visitor center complex were a result of such stresses. To insure confidence in the resulting system, and to accommodate the intended design loading, ceiling/beam junctions were reinforced in such a way as to allow the necessary freedom of movement. Steel angles were fabricated of one-inch thick plate for bolting to holes bored through the side of the beams. The steel angles (about 300 pounds each) were jacked into place against the ceiling and grouted into firm contact. Using epoxy patching material under the angles, extensive repairs were performed in two places where strength had been doubtful.

Water Intrusion Repair, JEFF, 1990 A Sequence of NPS Photos, Courtesy Dave Caselli

|

|

| Earth removal, August 21, 1990. | Dave Caselli examines exposed pipe, October 5, 1990. |

|

|

| The exposed visitor center roof, October 24, 1990. | Installation of Pave-Prep, October 29, 1990. |

|

|

| Installation of Pave-Prep, November 2, 1990. | Removal of old waterproofing material, November 7, 1990. |

|

|

| The finished visitor center roof, November 17, 1990. | Testing for water-tight qualities, November 26, 1990. |

|

|

| The exposed visitor center roof, January 9, 1991. | New installation of waterproofing material, February 2, 1991. |

|

|

| Replacing soil, visitor center roof, April 1, 1991. | The re-covered visitor center roof, April 11, 1991. |

|

| Resodding, May 1991 |

|

|

| Asbestos removal, January 9, 1991. | Temporary wall erected during asbestos entrance ramps removal, January 9, 1991. |

When the soil was replaced on top, a lighter material was put in place to increase the live load capacity. Where there used to be two to three feet of soil, which had been reshaped several times for drainage, there were now only 14 inches of a lightweight, cement-based, closed-cell polymer material covering the roof. Fourteen inches was selected as the correct depth since that was the shallowest amount the soil consultant would recommend. Each cubic foot of polymer fill weighed just 35 pounds, almost 2/3 lighter than the same amount of soil. This reduced the overall load on the roof by approximately 5 1/2 million pounds.

A 1990 health and safety survey documented the presence of asbestos throughout the building, and removal was begun in conjunction with the waterproofing project, starting with the highest identified priority — the ceiling surfaces in public areas. Kozeny-Wagner experienced some difficulties in establishing plastic-sealed containment areas to keep asbestos particles from leaking out into public areas. The facility was kept open, with first the north leg and then the south leg closed to visitors. Air flow supplied to the visitor area at the top of the Gateway Arch through the operating leg was found to pressurize the space behind the poly plastic at the bottom of the opposite leg and tear it from the walls. If the containment area had been breached during removal operations, asbestos might have contaminated the entire facility. This potentially major problem was solved by closing and sealing the doors on the side where work was progressing with tape at the top and bottom, then installing a filtered opening through the plastic to allow it to "breathe." [47]

The failure of the first waterproofing material delayed the completion of the re-roofing project. The excavation was left exposed to furious ice storms in December 1990 and January 1991. During the spring, sod and irrigation systems were finally laid into place. The contractor left the site on August 16, 1991, just meeting the completion deadline. The following day, construction crews arrived to begin setting up for the VP Fair. Following the VP Fair in September, the contractor delivered an additional quantity of sod and herbicide for application by the NPS grounds crew. The total cost of the project was $1,772,775.56. [48]

Part II: Grounds Maintenance

The look of the Gateway Arch grounds has been a major priority at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial since the Arch was originally designed, and for good reason. The park has just under 91 acres on which to host more than 2.5 million visitors annually. Since the Arch serves as a symbol of westward expansion as well as the city of St. Louis, the grounds must look their best at all times.

The original grounds foreman was Louis Whitman, who served from the 1950s to 1981, and set up the initial grounds care program. Whitman's program was continued under foreman Keith Biermann, who transferred to another park area during November 1984 and was replaced by Jim Jacobs in September 1985. Jacobs came to the park from St. Louis University, where he was responsible for the landscape program; he had extensive background experience in nursery work and a degree in horticulture. [49] Caring for the unique, man-made environment on the Gateway Arch grounds involved an extensive knowledge not only of horticulture, but several other disciplines as well. [50] A 1982 operations evaluation by the Midwest Regional Office mentioned "a pressing need to establish more formalized activity standards and to rely upon a resources requirements data process within the Grounds Branch of the Maintenance Division. This branch is just now beginning to deal with the professional maintenance of the rather extensive landscape developments which have recently been completed. Consequently, we recommend that defined standards, resources requirements data, and a documented maintenance program be developed for this operation as soon as possible." [51] Programs such as those mentioned evolved over the course of the 1982-1991 period. [52]

Duties

In 1977, the grounds crew consisted of a foreman, two tractor operators and six seasonal laborers. JEFF Facility Manager Bob Kelly built the crew to its 1991 size of a gardener foreman, a gardener worker-leader, an automotive mechanic, two tractor operators, two landscape gardeners, one full-time laborer, and 3-7 temporary laborers. [53] Duties of grounds personnel included emptying litter containers, snow removal, turf maintenance, pest management, tree maintenance, irrigation, landscaping and equipment maintenance. [54] Although the park boundary encompassed approximately 91 acres, the area maintained by grounds maintenance was about 66.1 acres, with a total mowable area of 47.5 acres. The park had the largest in-ground irrigation system in the state of Missouri, covering 49.8 acres, with 8 systems, 43 zones, 1,420 heads, and 13.5 miles of pipe. The system was partially computer-based and partially manual in operation. The crew maintained 2,551 trees (28 species), 7,200 shrubs (4 species), one acre of wintercreeper euonymus, and 700 square yards of display flower beds. [55]

|

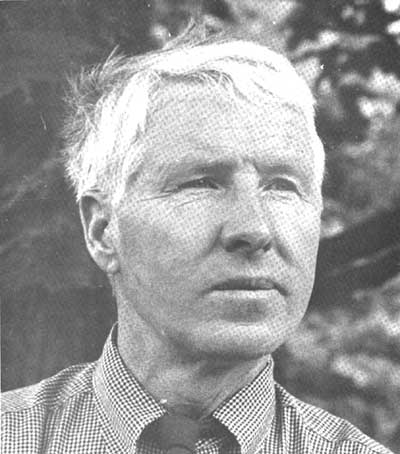

| Grounds Foreman Jim Jacobs |

Landscaping

In an article about the Arch grounds, James P. Jackson stated that "The most ambitious urban forestry project ever undertaken in the St. Louis area was the landscaping of the area surrounding the Gateway Arch." [56] The original landscape design for the park was created by Dan Kiley, one of the country's leading contemporary landscape architects, who worked with Eero Saarinen from the beginning of the memorial competition in 1947. Regional Landscape Architect Mary Hughes summarized the contributions of Dan Kiley to the Arch project in a 1991 memorandum:

In 1961, Saarinen wrote Kiley to say the Director of the National Park Service (NPS) Conrad Wirth wanted NPS landscape architects to take over the design of the Gateway Arch landscape, to which Saarinen objected. A compromise was worked out by which Kiley would continue to carry the project through the design development phase, after which the NPS would take over preparation of working drawings. [57]

In the early 1960s, there were numerous versions of the landscape plan discussed in meetings attended by Kiley, Saarinen (or other members of his staff), Park Superintendent George Hartzog and Conrad Wirth [Director of the NPS] . . . . In the course of these meetings, the final shape of the landscape evolved into the site plan we see today: curved, tree-lined walks, large expanses of open lawn, and lagoons. Although the first phase competition drawings show a heavily forested site, the second phase drawings . . . reveal a large opening at the center of the site to permit views of the Arch from Memorial Drive. By the early 1960's, the trend toward a more "open" site was even more pronounced. . . . Tree massing was limited to lining the walkways and defining the edges of the open meadow spaces. In early 1963, Conrad Wirth expressed concern [that] the tree plantings along the walks were too dense, blocking pedestrian views of the Arch. Kiley then adjusted the plan into the scheme which received NPS approval. [A] letter dated September 17, 1963, authoriz[ed] Kiley to prepare color-rendered presentation drawings based on a plan reviewed by NPS officials, including Conrad Wirth and George Hartzog, in July of 1963. [58]

|

| Dan Kiley was the original landscape architect for the grounds of the Gateway Arch. Courtesy of the Office of Dan Kiley. |

Eero Saarinen, the designer of the memorial, had been insistent that Kiley execute the landscape plan, but this was not to be, and Kiley's last association with the project was in 1964. [59]

The planting plan was redesigned in 1966, with the trees spread out more thinly than Kiley had advocated. There were three reasons for this alteration; first, to allow for open areas providing long views of the Arch and other groups of people, creating a safer pedestrian space; second, to allow for more natural, open-form trees; and third, to save money. [60] As NPS designers saw it, the goal of grounds development was to complement the Gateway Arch with ample open space, pleasantly contoured, and to enhance the generous approach views. [61] The park landscape plan was finalized by National Park Service personnel in Philadelphia, and included the preparation of master plans, development concept plans, preliminary drawings, construction drawings, and contract documents based on Kiley's original plans. [62]

The landscaping was complicated due to the unique nature of the Arch itself. Before the Arch was built, windtunnel studies were made to determine whether the structure could withstand high winds. The original grading plan and these studies were combined to obtain the proper elevation at each end of the north-south walkway. This elevation was pre-determined by the windtunnel studies and mathematics, and had to be 478' above sea level, making these the highest points of land on the Arch grounds. If this landscaping were changed, winds would eventually put too much stress on the Arch structure. The same studies also determined that a dominant tree species should be planted of the type which would reach a mature height of 100' to 200.' The dominant species of tree, in addition to aesthetic appearance, was meant to help deflect north-south winds in line with the Arch. The species selected had to live long enough in the St. Louis climate and urban environment to attain its full height. [63]

A great deal of pressure was exerted by the local community, through their representatives in Congress, for the project to begin. "The approach of planting time gives urgency to the question whether the Gateway Arch shall stand for another year amidst the weeds, or whether at least a modest start will be made toward giving the riverfront its intended park-like appearance," ran an editorial in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. "It can be left to Washington to decide when and if the museum beneath the site is to be completed. Meanwhile the space provided for it may be screened off, it will offend nobody. But there ought to be no further delay in landscaping, its basic phase ought to be undertaken this spring." [64] Superintendent LeRoy Brown answered the editorial in a letter to the editor, patiently explaining that underground utilities, including area lighting and an irrigation system, had to be installed before final landscaping could begin. Brown also emphasized that interior work in the visitor center complex would take priority over the landscaping. [65] An interim landscaping plan, "to beautify the memorial grounds for the probable dedication [of the Gateway Arch] this coming spring or summer," was approved in March 1968, with severe modifications which eliminated permanent plantings. [66]

In 1968 John Ronscavage, who then worked for the NPS's Eastern Office of Design and Construction, was assigned to the landscaping project on the Arch grounds. He was ordered to follow the modified Kiley plan without alteration. He met with Superintendents LeRoy Brown and Harry Pfanz, who discussed the project with him. [67] A tree planting plan was drawn up, which outlined four phases of implementation. [68] When the first contract for landscaping was advertised, however, local nurserymen criticized the NPS for their projected selections of tree species for the grounds, specifically the tulip poplar, which had been the first choice of landscape architect Kiley. An objection was made over the poplars due to the perceived problems of air pollution and potentially toxic riverfront dirt. It was felt that the trees would not thrive under the conditions presented by the Gateway Arch grounds. A press and television conference was held on March 11, 1970, which was attended by "a group of nurserymen from the Greater St. Louis Nurserymen's Association and from the Arborists Association" at Stouffer's Riverfront Inn, to protest the proposed plan on which bids were to open. Letters were sent to Congressperson Leonor Sullivan and Senator Thomas Eagleton. [69] Congressional inquiries were answered, saying that the "National Park Service retained the planting list of the Kiley plan; however, we did revise the plan as it pertained to plant composition and open space. . . . The Park Service has given considerable study to the design to ensure the success of the planting. . . . Regarding the selection of plant species, the city forestry department concurs in the plants proposed. . . we believe we are making every effort to create a landscape for the memorial site in keeping with [Kiley's] winning design concept, which will be a credit to St. Louis and the Service." [70]

Due to a barrage of criticism, however, John Ronscavage began an intensive period of research, along with Superintendent Harry Pfanz, into the best tree to use as the dominant species on the grounds. They met with soil conservation people, urban foresters, botanists, Wayne Sefer (a professor of soil conservation at the University of Illinois, Edwardsville), and the director of the Missouri Botanical Garden. [71]

A meeting was held in the Old Courthouse with Jim Holland, Ted Rennison and representatives of the City of St. Louis. In addition to expert objections to the ability of tulip poplar trees to survive the climate and the soil, they were not available in enough numbers for the initial plantings. The best regional source for poplars was in Tennessee, which fell within a different climactic zone than St. Louis. Ronscavage determined that tulip poplars would not be hardy enough for St. Louis, referencing climactic zone maps while formulating his decision, and proposed that the dominant species for the park be changed. [72] The group made a list of trees, tallying the pros and cons of each type. The first runner-up on this list was the pin oak (Quercus palustris). [73] This species lost out due to St. Louis' soil content, which has a high pH value (meaning it is alkaline); the pin oak prefers a low, somewhat acid pH. The final choice of the committee was the Rosehill Ash (Fraxinus americana). This species, a seedless male clone of the White Ash, was developed specifically at the Rosehill Gardens in Kansas City as an urban tree, meant to replace the American elm, which had been decimated by the Dutch elm disease in the 1950s and 60s. The Rosehill Ash had many advantages; it was hardy, and would thrive in the alkaline St. Louis soil; it was native to the midwest region, and had been bred for an urban environment. It would grow to an adult height of 60' to 70', shorter than Kiley's original species choice. The NPS was given a very reasonable price on these trees, and went sole source on the bidding. Ronscavage consulted the Soil and Plant Lab at Palo Alto, California, which confirmed the soundness of the choice of this tree.z [74] Kiley's grading plan was also revised by Ronscavage, and given to Harland Bartholomew & Associates for refinement. [75]

Once the design was completed, the first phase of the landscape project undertaken was the construction of walkways, plantings, and grading immediately around the Arch. In June 1970, [76] a contract began with Kozeny-Wagner Inc., for site work to the north and south of the Arch. The $474,064 contract included grading, seeding, drainage and roof repairs to the underground visitor center. [77]

Site grading was designed to direct surface and subsurface drainage to the two ponds, and catchbasins on the walkways by the Grand Staircase. In addition to providing an aesthetic feature, the ponds had a practical application as well. Water was drained from all exterior surfaces of the underground visitor center and ramps to protect the building interior, and then pumped to the ponds. [78]

Artificial hills created sight and sound barriers, alleviating the noise problem from the highways which surrounded the park. [79] Below these hills, the most extensive underground irrigation system in the State of Missouri was installed, with 9.5 miles of pipe and 900 sprinkler heads. [80] An excess quantity of excavated soil and rubble removed while building the ponds allowed for mound construction along Memorial Drive. Rubble materials were buried deep, while better soils and 8" of topsoil were provided to sustain trees, grass and ground cover. A considerable cost savings was realized by not transporting excess soil off site. Soil monitoring and evaluation were performed during construction to minimize the importation of topsoil. [81] A contract was awarded to Suburban Tree Service of Manchester, Missouri, on November 9, 1972, to perform the first phase of planting on the Memorial grounds, including furnishing 573 trees. [82]

Though designed primarily to accommodate the pedestrian visitor, grounds development helped to complement the Arch in aesthetics and function. The walks were designed to provide access to the Arch from all corners and sides of the memorial. To the north and south of the Arch, scenic overlooks were built on the river side of the property. The overlooks provided an aesthetic balance to the Arch when seen from the river, as well as constituting an extension of a flood wall system. Wharf Street (later re-named Leonor K. Sullivan Boulevard) provided access to the new riverfront, and was handsomely landscaped with trees and benches. The massive, curving grand center stairs, leading from Wharf Street to the Arch, were designed to sweep the eye upward to the crest of the hill. Landings provided rest areas and view points. The curvature of the walks was designed to complement and reflect the bold form of the Arch, and the integrated tree rows further reinforced that form. A walkway leading to the historic Old Courthouse from each leg of the Arch was also designed, and plans were made for two pedestrian overpasses over Memorial Drive. The pedestrian circulation system on the grounds provided an aesthetic unification of all the features of the memorial development. All areas of the grounds were accessible, except for the stairways down to Wharf Street, where extremely steep grades existed. [83]

From January 9, 1978, to April 20, 1980, Mike Hunter of the Denver Service Center worked as project manager on extended duty at JEFF. Hunter supervised the $2.89 million next phase of the landscaping project, contracted to Schuster Engineering of Webster Groves, Missouri. Concrete placement, construction of retaining walls, flat work, exposed aggregate walks, roads, completion of the ponds, and drop inlets were part of the package. The project involved earth movement, irrigation systems and backflow preventers to municipal water systems, walk lighting, seeding, sodding, fertilizing and mulching of grass areas, and the creation of storm sewer and discharge areas. [84]

The planting plan for the Gateway Arch grounds was a $1.03 million project. Phase I involved turf renovation on the 8-acre levee slope along the Mississippi River, and tree plantings to curb strong winds on the grounds. In 1979, Shelton and Sons Landscaping of Kansas City, Missouri, followed the Phase I plans designed by the Denver Service Center. The levee area required the elimination of temporary ground cover, which was replaced with a mixture of bluegrass, fescue and ryegrass. After removing several thousand Bulgarian ivy and wintercreeper euonymus plants in a 3-acre grass-infested plot, the crew sprayed the area with Roundup herbicide, waited for it to dry and then replanted. According to Mike Mayberry, crew chief for Shelton and Sons, the infested grass was eliminated in one day, less time than mechanical means would take. [85]

During 1978, trees were planted along the walks to the "teardrop" sections north and south of the Arch; by 1980, the concept of Rosehill Ash plantings was complete, with the walks finished up to the overlooks at the north and south ends of the grounds. [86] The park had more than 6,500 shrubs and 1,700 trees by 1980, including Rosehill Ash, Japanese black pine, oak, maple, bald cypress, redbud and flowering dogwood. [87]

The second phase of landscaping was begun during the summer of 1980, and completed by the fall of 1981. This $4 million project resulted in five miles of paved sidewalks, the completion of two reflecting ponds of 1.7 acres each, and an irrigation system which now totalled 12 1/2 miles of pipe (with 875 sprinkler heads), for a lawn area of 46 acres, as well as 2,495 trees, 6,500 shrubs and 5.5 acres of ground cover. [88] Mike Mayberry supervised completion of the irrigation system out into the smaller areas of the parking area and the planting beds between the railroad tracks and the Arch. The contract bid for this work went to Harland Bartholomew & Associates. Completion of this contract put the Arch grounds at optimum appearance. [89]

Superintendent Jerry Schober was not completely satisfied with the contractors on this phase of the landscaping, however.

[S]omething that bugged me there and I raised so much H-E-L-L over it that I got a contact person from the Denver Service Center. . . . I think I found to the tune of four hundred thousand dollars of boo-boos in the contract. . . I said [to the project supervisor]: "You know, look at this, here are a number of errors." For instance, there was $80,000 worth of black paint to put on the bottom of the reflection pools to mix with concrete. "Wait a minute [I said]; it's going to turn dark in nothing flat. You have dirt washing right down into the pond, and it will darken the bottom, you will get the same reflection. Why do you need to introduce it?" Then on top of that they had plans drawn up in 1972, that they did not look at from a safety standpoint. The first thing they said to me was: "Those reflection pools are too deep. If you bring the water level up to where it was originally designed to be you will have to put up cyclone fence all the way around." That would make a very attractive reflection pool! . . . Or signs every six feet that say this is a dangerous area and to stay clear. [They asked] "Well, what can we do?"

"If you can drop the water basin to twenty-seven inches . . . then we'll be able to live with it." So the next proposal I got was for a hundred and eighty thousand dollars to raise the concrete floor up to where the water would [only be 27" deep]! And I said, "Guess what? I got a better idea."

"What is that?"

"For about twenty-five dollars on each one I can get them to come in here and cut that drain stand pipe off at twenty-seven inches. No water can go higher if it keeps running over it." Well, they quickly said they knew that could be done. I don't know why they did not tell me that, but anyhow, they said this will keep people from seeing the part of the wall which won't be covered by water. Well, if I find that offensive I can let ivy run down the walls. As it was nobody ever complained that it looks ugly. . . .

Then I found out that the mix of the peat and soil was way off. Another multi-thousand dollar mistake. So when I came to the project supervisor I said, "Now, you did not get a chance to see this prior to being made project manager, did you? To read over it and all that. You just inherited this as an assigned job, didn't you?"

"Oh, heck no, I saw the project in advance."

"And you did not catch this?"

"Oh, guess I didn't."

See, I would make a recommendation that before contracts begin in the park that the engineer also has to come and explain it to a stupid superintendent like myself. Because you get frustrated. It is like the time my wife came out when I was working on the wiring on my car. It was in California and about a hundred degrees in the sun, and she said, "Why don't you tell me what you are doing so I can help you?" And I'm thinking she does not work on vehicles at all. Why would she come out here and say this? And I knew if I got angry it was going to be offensive to her. And so I said "O.K. . . . hold on. This is a battery, from that post the wire goes to here, and from here — Wait a minute! There is my problem!" You know what? I had looked at that same diagram half the morning. But when I had to explain it in a nice, simple way, the problem stood out.

I am saying, if the engineer says, I know this may be a little boring but here is what we are going to do. That allows me as a manager to say, why would you put black into the concrete mix?. . . . And then as we get to discussing it he'd say, wow, that mix isn't necessary. We'd take that one out. But instead we sent someone home with a big packet of plans and it probably put them to sleep to read this sucker anyhow. If they would take the time to explain it to the managers, I think it would work far more effectively. [90]

During the hot, dry summer, Mike Mayberry of Regency Landscape, again working for Shelton and Sons Landscaping, planted and pruned the new trees. Since the lawns had already been hydroseeded, planting the new trees the contract called for would almost certainly cause severe damage to completed landscape areas by trucks and heavy equipment. [91] Superintendent Jerry Schober suggested an alternative method of putting in these trees which would not damage the completed lawns. [92]

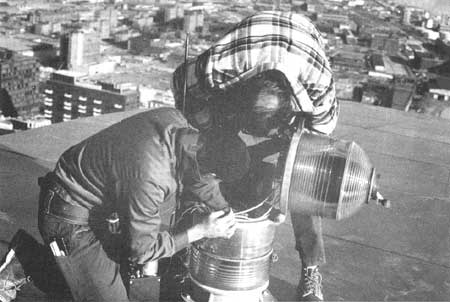

I mentioned to [the contractor], why don't you plant the things by helicopter? And the contractor said, "What? Do you know how much that would cost?" I said: "Well I see them haul trees in, take them off the truck, and put them down, and to do that, you'll have to drive across the grass. Then you'll have to come back in and reseed, and take all those ruts out. It's going to take you longer. You are in arrears now on time. I just thought . . . " We never said any more. Later I got a call, sitting up here in my office in the Old Courthouse, and it's Robin Smith. Tough, near perfect newsperson here at [Channel] 4. And she said, "I want you to come down here." And I hear bop-bop-bop. It's the helicopters. They are taking the trees straight off the trucks, that brought them here from Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and they're taking them right out, setting them down in the holes. Not disturbing anything. That might be the first time in a National Park that we ever planted trees by helicopter. Sure did work fast. [93]

|

| Balled trees are planted by helicopter on the Arch grounds, December 1980. NPS Photo. |

Helicopters were rented from Fostair Helicopters on the riverfront, and used to airlift trees from delivery trucks to their final locations on the grounds. This method was primarily used on the North end of the grounds, particularly around the reflecting pond. These trees included Japanese Black Pines, Mugo pines, and sumac. English Ivy and euonymus ground cover were used on the slopes toward the railroad tracks. In the open areas, burr oaks, Japanese pagoda trees, locusts, radiant crabs, dogwood, Bradford pears, red oaks, Washington hawthorns, greenspire lindens, and coffee trees were planted. The remainder of the walks were also installed on the grounds. [94]

Tree and Groundcover Replacement

The park walks were lined with a total of 965 Rosehill Ash trees. Urban areas such as the Arch grounds constitute a difficult environment for trees because of air pollution, "heat islands" caused by concrete construction, poor soil conditions, and lack of space. St. Louis' particularly difficult conditions were due to high levels of ozone and sulfur dioxide, and extremes in weather, most notably temperature and rainfall. [95] The park's trees remained in very good shape over the decade of the 1980s, considering these physical conditions. Several experts stated that based on their experience, the original trees recommended by landscape architect Dan Kiley would not have managed nearly as well as the Rosehill Ash in St. Louis. Due to urban environmental factors, however, replacement of trees and plants has been necessary at periodic intervals. [96]

On September 26, 1985, a contract was awarded to Treeland Nurseries to furnish all labor, tools, equipment and shrubs for replacing plants such as Mugo pine, "Lalandi" firethorn, and fragrant sumac on the Memorial grounds at the top of the levee slope, south of the central stairway; along the fence line and the open railroad cut, north and south of the stairway; on the slope around the south service entrance to the visitor center; and around the fenced area of the generator building and northwest service entrance. This project was completed on May 27, 1986, and a similar contract was awarded on September 23, 1986, again to Treeland Nurseries, to replace dead trees on the grounds. With the completion of this second replanting project on December 19, 1986, the park tree inventory was restored to within 92% of the original number planted. [97] The grounds crew planted 68 of these new trees, while Treeland Nurseries planted a total of 110 trees and 1,330 shrubs. [98] Another project called for transplanting twenty-eight 4-6" Rosehill Ash from less visible locations on the grounds into the tree pits that line the Arch walks. This contract was fulfilled by Davey Tree Service, and by the end of the growing season only one tree had been lost. [99] Hillside Gardens successfully completed a contract in November 1988 to replace 186 trees of 18 species. This project brought the tree inventory to within 96% of the total originally planted on the Memorial grounds. [100]

|

| The completed grounds as seen from the top of the Gateway Arch, 1990. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

The park supported the efforts of the national "Global Releaf" organization in 1989, when seven trees were planted on the Arch grounds, drawing significant media attention to the park. Additionally, the park participated in the American Forestry Association's Urban Tree Workshop, as co-host for a reception and as part of the teaching staff. [101] Work with Global Releaf continued as the park attended planning meetings and assisted in the nation's largest single tree planting event on Earth Day of 1990. Ten thousand bare root trees were planted in a single day on two sites in the greater St. Louis area. The park donated equipment, tools and radios for the event. Gardener Foreman Jim Jacobs supervised site transportation and communications while Tractor Operator Sharron Cudney assisted in the preparation and transportation of trees. [102] The grounds crew also supported the Girl Scout Council of Greater St. Louis in a service project on April 6, 1991, called "Earth Matters: Branching Out," during which Girl Scouts replaced 45 missing trees on the Arch grounds. The Grounds staff selected and transported the trees from Forrest-Keeling Nursery in Elsberry, Missouri, dug holes, mulched, watered, and staked them in place. [103]

Pruning

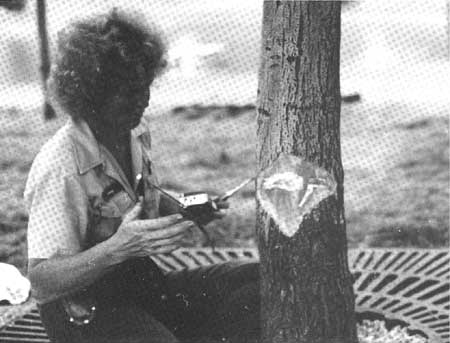

On February 25, 1987, a photo appeared in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of Gardener Carl Smith, with a simple caption stating that the "2,800 trees on [the] Arch grounds are pruned back each winter." [104] On March 2, a letter to the Editor of the Post-Dispatch criticized the practice of pruning, saying that "responsible people like the Missouri Department of Conservation have been trying to educate us for years to refrain from such nonsense. . . . It makes about as much sense as cutting back human limbs for the sake of appearance and health. The practice weakens the trees in weathering future storms, promotes disease, shortens the life of the trees and makes them look terrible." [105] In an unsolicited response, Skip Kincaid of the Missouri Department of Conservation replied, for publication, that the letter to the Editor made "a comment that the Missouri Department of Conservation encourages people to 'refrain' from tree pruning."

Nothing could be further from the truth. We strongly encourage management of our urban trees, which includes proper pruning techniques. . . . Pruning at the Arch grounds is done by a very well trained and knowledgeable staff. Foresters with the Missouri Department of Conservation have worked with the staff at the Arch grounds to keep them up to date on urban forest management. We are continually impressed with the quality of work that is performed.

St. Louisans can be proud to have a showpiece like the Arch, and a tremendous urban forest that is developing beneath it. I encourage residents and visitors to visit the grounds and see, first hand, what quality urban forest management . . . looks like." [106]

The division received Worker's Skill Training Funds for six crew members to attend an Arborist Skills Workshop which included tree climbing and maintenance techniques. The course, held in September 1987, was attended by members of the City of St. Louis and the University City Forestry Divisions. Pruning was originally performed using ladders and a self-propelled lift. During two training sessions, in September 1990 and March 1991, the grounds crew learned the proper way to climb trees, and how to prune using ropes and saddles. [107]

Pruning was performed on alternate years after fertilization. In 1991, the grounds crew used their newly-acquired climbing skills to remove several dead and hazardous trees at the new Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site (ULSG). [108] Improved pruning techniques have resulted in more professional and scientific care for the park's urban forest. [109]

The division received further funding for six crew members to attend a second Arborist Skills Workshop for training in advanced tree climbing, cabling and bracing techniques. The course was held at ULSG in March 1991 in conjunction with a one-day Hazardous Tree Program. Both seminars were attended by members of local arborist companies, municipal arborists, and NPS personnel from Herbert Hoover NHS and Lincoln Boyhood NHS. [110]

Integrated Pest Management and the Ash Borer

The completed grounds of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial had more in common with a golf course or an athletic field than with natural parks such as Yellowstone or Yosemite. All features of the landscape were designed, built and planted by man. Many of the trees, shrubs and lawn grasses were exotics. The main goal in managing these plants was to keep them as healthy as possible. Cultural practices such as pruning, mowing, watering, fertilizing, insect and weed control were all meant to give the desirable plant an advantage over the undesirable pest. On those occasions where pesticides were required, the decision to use them was made after considering many alternatives and consequences. Several factors led to the use of pesticides in JEFF's urban forest during the 1980s. Integrated Pest Management (IPM), a decision-making process that utilized the monitoring of pests to determine if and when treatments were needed, employed physical, mechanical, cultural, biological and educational tactics to keep pest numbers low enough to prevent intolerable damage or annoyance. Least-toxic chemical controls were used as a last resort; improving or managing plant health was considered to be the key. [111]

Not long after planting more than 900 Rosehill Ash trees on the Gateway Arch grounds, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial unwittingly became the foremost regional host for the Lilac or Ash Borer (Podesesia syringae). [112] Clearwing borers comprise one of the most damaging groups of insect pests which attack shade trees and shrubs. Included in this group are the dogwood borer, lilac/ash borer, rhododendron borer, oak borer, and peach tree borer. It is the larval stage of the borer, and not the adult moth, which causes the damage. The larvae burrow beneath the bark where they feed and tunnel, weakening trunks and destroying the tissues that transport food and water throughout the tree. As Superintendent Jerry Schober put it, "our trees began to look like they had been shot with automatic 22 rifles, there were so many holes . . . . Some of our first trees that were damaged, I think were due to the wind in '82. We woke up one morning and had about nine trees just snapped right in the middle. And part of it was because so much damage had been done by the borers." [113]

The clearwing moth spends the winter as a larva under the bark of the host plants or in the adjacent soil. Following pupation, the adult male clearwings begin emerging, followed shortly after by the females. The females immediately begin emitting a pheromone (sex attractant odor); males are capable of detecting the pheromone with their antennae, and fly upwind toward the female until they locate and mate with her. Females typically mate and begin laying eggs on the same day that they emerge. Approximately ten days elapse between egg deposition and larval hatch. Larvae bore into the bark of host trees soon after they hatch. [114]

Control of the clearwing borer became imperative at JEFF during the 1980s. No insecticide was sprayed during the late 1970s, and before 1983 the grounds crew used squirt bottles to spray the small holes on the trees where the borers emerged. Wires were also pushed into the holes to kill borers during the early 1980s. These methods were unscientific and not commensurate with the growing problem. Insecticide spraying began in earnest after 1983, when entire trees, rather than just the borer's holes, were sprayed. The Missouri Department of Conservation assisted in the efforts of the park staff to gain permission for spraying by writing letters, as did the USDA Forest Service. By that time the trees were badly infested and threatened by the ash borers. [115]

Accurate timing of insecticide applications was the critical factor in reducing clearwing borer damage. Larvae were only vulnerable to insecticide from the time they hatched until they burrowed beneath the bark, a period of one day or less. Insecticides with long residual effectiveness were generally unavailable. Monitoring the emergence of adult clearwing borer males with sticky traps laced with synthetic pheromone provided the needed information to accurately time insecticide applications. The traps were located by the male ash borers, [116] where they became caught on the sticky surface. The number of males caught in this manner indicated the presence and population of the borers in a given area. Traps were put out two weeks before the anticipated emergence of males, and if six or more clearwing borer moths were caught in an individual trap within a ten-day period, an insecticidal spray was applied. [117]

In 1985, four applications were made of Dursban 4E, a common insecticide proven to be effective against ash borers. By 1986, only three Dursban applications were made, and during pruning operations, the grounds crew found no significant infestation of borers in the ash trees. In 1987 this was reduced to two applications, and during 1988 and 89, just one. Traps revealed a five-year low of just 95 adult males in 1988, and no evidence of damage as of January 1989. [118]

Meanwhile, other untreated species of trees showed an increased infestation of borers (other than the Ash Borer). Monitoring of these species was increased in 1989, and for the first time, trees other than ash were treated. [119] Insect pest problems on the increase in 1989 included the eastern tent caterpillar on crab and hawthorn trees, scale on euonymus ground cover (a serious problem in isolated areas), and spider mite on cypress trees. [120] Eastern tent caterpillar infestation increased from none prior to 1987 to 45 nests in 1988 and more than 100 in 1989. Mechanical removal was followed by two applications of Dipel pesticide. All crabapple trees were inspected for egg masses during the winter months. Eastern tent caterpillars were far less of a problem by 1991, but hardwood borers of several species continued to infest trees in stress. [121]

Another major problem from 1985 through 1987 were white grubs (the larvae of beetles such as the Northern Masked Chafer). In 1986, after a second year of extensive damage caused by these grubs, a request was approved to apply Proxol 80sp to more than 20 acres of lawn area. Control was quick and efficient; however, the problem continued through 1987. Proxol was approved at levels of 5 grubs per square foot. No significant white grub damage was made to the turf in 1988, due largely to the successful control measures taken in the two previous years. Damage caused by Masked Chafer grubs to lawn areas required the treatment of eight acres in 1991, however. May Beetle and Bluegrass Billbug were also found, but not in significant numbers. [122]

The Japanese Beetle was rapidly moving west during the mid-1980s, but significant turf and ornamental damage were rarely found on the Memorial grounds. Milky spore to control Japanese Beetles was applied beginning in 1985. Despite this, the occurrence of Japanese Beetles rose dramatically during the late 1980s, with 844 beetles trapped at 15 sites in 1987, and 3,264 beetles trapped at 20 sites the following year. Other areas monitoring Japanese Beetles in Eastern Missouri experienced similar increases. Japanese Beetles were monitored in the park by the Missouri Department of Agriculture and the Missouri Department of Conservation. No Japanese Beetle grubs were found in 1991, but adult monitoring showed an increase of 92% over 1990 totals, and damage by adult feeding was found on canna plants. [123]

Indications in 1990 were that IPM control methods had limited clearwing borer damage. Monitored trap counts were approximately the same as the year before, and consequently, no Dursban applications were made for the first time since 1984. The program seemed incredibly successful. Gardeners Mike Dobsch and Carl Smith attended a 40-hour IPM course held in St. Louis, making a total of five staff members who held IPM licenses. Counts early in 1991 were lower than the past two years and delayed control measures. The grounds crew were concerned by the monitoring of borer activity, however, which indicated two to three borers in 75% of the trees sampled. These results were ominous, since borer infestations had been almost nonexistent since Dursban use was begun in 1985. [124]

Other problems also appeared. Slow leaf development, die back, along with canker and bark sloughing on the park's Rosehill Ash trees were a cause for concern starting in late April 1991. Monitoring by Gardener Mike Dobsch in June found at least twenty trees showing advanced signs of die back with many more showing lesser symptoms. Site visits by urban foresters from the Missouri Department of Conservation and the City of St. Louis in June confirmed symptoms associated with ash decline. Heavy infestations of Ash Plant Bug (Tropidosteptes amoenus), a possible vector of Ash Yellows and other mycoplasma-like organisms, led to the conclusion that control measures were required immediately. After foreman Jim Jacobs consulted Midwest Regional Office IPM Coordinator Steve Cinnamon, the grounds crew sprayed the most heavily infested area with Dursban 4E under pest project JEFF-91-08. [125] Soon afterward, a large number of dead birds were noticed on the grounds. Although Jacobs was unsure that there was a connection between the dead birds and Dursban applications, Chief Ranger Deryl Stone shut down IPM operations for the remainder of the year. [126]

In August, the national meeting of the American Phytopathological Society was held in St. Louis. Attending the conference were James L. Sherald, plant pathologist, National Capital Region, NPS, and Manfred E. Mielke, plant pathologist, USDA Forest Service. They had been made aware of the Rosehill Ash problem prior to their visit, and organized an informal walk with several of their colleagues. While there was no immediate diagnosis, the collective opinion of the group was that Ash Yellows was not a problem in the park. While symptoms of decline were certainly present, the canker was probably a secondary result of a greater problem, most likely limited root space, compaction, and the effects of the drought of 1988. Applications of Dursban were resumed in 1992 on a more limited basis, and research continued through the use of consultants into the most effective and non-destructive uses of pesticides on the grounds. [127]

In reference to this, Jerry Schober commented: "I think the Park Service is very concerned, and I don't blame them, in what chemicals we put out. [We have visitors] nearly around the clock except for six hours. So we have to be careful what we spray, in order to protect the environment." [128]

Bermuda Grass and Weed Control

Beginning in 1987, the grounds division began a project to eradicate Bermuda grass and other weeds. More than four acres of spot treatment with Roundup herbicide were followed by complete turf renovation in 1987, with additional treatments necessary during the spring and summer. This program was continued during 1988, when less than one acre of turf required spot applications. As a result, control and treatment were performed on an as-needed basis. In 1989, approximately 1/4 of an acre of slope was renovated in this manner, and later sodded by grounds personnel. [129]

Restrictions were placed on the use of pre-emergent weed control products in 1988, however, and weed problems in plant beds started to become significant. The lack of an appropriate selective post-emergent control also contributed to annual grasses and broadleaf weeds, which required intensive hand weeding, performed by Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) crews. The incidence of perennial weeds including thistle, bermuda grass, crab grass, clover, wild onion, and nutsedge increased significantly over previous years. [130]

To control these undesirable plants, YCC began installing weed barrier material under the trees in 1988. The park funded this project to test the effectiveness of geotextile turf covers in the protection of lawn areas from heavy foot traffic. The material protected the turf in most situations. [131] By 1989, YCC crews completed the installation of turf covers on 1,350 trees (80% of the trees in turf areas and 50% of the tree grates in the park). These non-woven geotextile fabrics were also a part of the IPM process, eliminating most of the need for weed-control pesticides once they were in place. The fabric was stapled and mulched to hold it in position. Roundup herbicide was approved for one application per year, only prior to placing the fabric. Safer's Sharpshooter was approved on an experimental basis as a post-emergent. [132]

Weed problems in plant beds, however, continued to be significant due to the restrictions on pre-emergent weed control and the lack of an appropriate selective post- emergent control. A sharp decrease in seasonal laborers and the cancellation of the YCC program in 1990 and 1991 greatly reduced the amount of time available for hand weeding, and perennial weeds increased significantly. The program to eradicate Bermuda grass from the park continued, as did the removal of scale on euonymus groundcover, found significantly at the Arch Parking Garage and in other isolated areas throughout the park. Complete plant removal and treatments of horticultural oil had not checked the spread of scale by 1992. [133]

Tree Inventory

During the 1980s, JEFF adopted a very efficient approach to monitoring the trees on its grounds. The Missouri Department of Conservation supplied a person to assist with tree assessment and inventory work in 1989. Each tree was tagged with a red plastic label with a code designating location, species and tree number. This information could be loaded into a computer at the Grounds Maintenance shop. A system was developed to assign point values to significant features of each tree, including the condition of the trunk, structure, vigor, and presence of pests. A cumulative point value was aligned with the MMS Feature Inventory Condition Assessment for condition levels of 1 (satisfactory), 2 (fair), and 3 (poor). A contractor was hired to produce a computer-generated map identifying all trees by zone, species, tag number, and relative size. A total of 2,551 trees were located and recorded on the map. Condition assessments were only made for trees other than Ash during 1989, however. Of the 1,558 non-ash trees, 56% rated as condition 1, 33% condition 2, and 11% as condition 3. Maintenance requirements, such as fertilizing and pruning, were noted. This information helped the grounds crew to treat each tree according to its needs, rather than work from orders for mass pruning or spraying, as some parks and golf courses are managed. Each year, two-thirds of the Arch grounds trees were inspected for pruning, with about half of them being pruned. [134]

The tree species performing best on the park grounds included burr oak, swamp white oak, thornless honey locust, bald cypress, red oak, the saucer magnolia, the Japanese pagoda tree and the Kentucky coffee tree. Many trees had slight problems. All Bradford pears that needed removal were replaced with Redspire pear trees, while Amur corktrees were used to replace dead lindens. Those trees with the most serious problems, which were not replanted, included flowering dogwood, greenspire linden, sugar maple, and white pine. [135]

Mowing

The Gateway Arch grounds were planted with grass seed known as "Arch Grounds Seed Mix." The Veiled Prophet Fair supplied 1 ton of this seed mix each year to the park. The mix consisted of 49% arboretum bluegrass, 15% regal ryegrass, 15% creeping red fescue, 10% glade bluegrass, and 10% Kentucky bluegrass, and was sold on the market. [136] From April through November, every weekday was mowing day somewhere on the Arch grounds, unless the grass was wet, when mowing was avoided due to the spread of plant disease. The crew mowed the grass high, with mowers set at 3" to 3 1/2", as long grass looks greener than grass that is cut too short. Each morning as the temperatures rose, laborer Gary Amstutz made the rounds of the 1,150 sprinkler heads, turning on those in selected zones so that the water ran through the 13.5 miles of underground irrigation pipe to keep the grass green. Sprinklers were turned off by 9 a.m. [137]

Snow Removal

During the winter, the grounds crew met the challenges presented by St. Louis' infrequent snow storms; with each snowfall, four sets of concrete steps and five miles of concrete sidewalks had to be cleared. [138] In January of 1991, a combination of sleet and snow kept walkways in hazardous condition for several weeks. The grounds crew performed three times the level of snow and ice control that had been planned for that winter. [139]

|

| Tractor Operator Bobbie Eakins aerating turf near Memorial Drive, 1991. NPS Photo. |

Reflecting Ponds

In 1986, a leak was discovered in the north end of the south reflecting pond at two inlets. Members of the grounds and HVAC crews repaired the leak after the pond was drained. The grounds crew and YCC cleaned the pond, which was then refilled. The following year, both the north and south reflecting ponds were drained and, after a thorough cleaning, the walls and floor of each were recaulked. Cyclic funding made available for this project, combined with other similar projects, resulted in a savings to the park of more than $40,000. A repair/rehabilitation project to modify the existing storm drainage system was also completed, with 530 feet of 18 inch PVC pipe and two manholes installed to divert storm water directly into the reflecting ponds on the grounds. [140]

Flooding

During October 1986, severe flooding of the Mississippi River resulted in damage to turf areas and cobblestone walks along Leonor K. Sullivan Boulevard. A request was made to the Midwest Regional Office for emergency funds to replace approximately 3,000 yards of sod and cobblestones. The resodding of one acre of turf along Sullivan Boulevard was completed the following autumn. Repair of the area was delayed so as not to be affected by the VP Fair. A major tuckpointing job of the cobblestones along Leonor K. Sullivan Boulevard completed the large project. [141]

Parking Garage