|

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

Administrative History |

|

|

Administrative History Bob Moore |

CHAPTER TEN:

Division of Law Enforcement and Safety

|

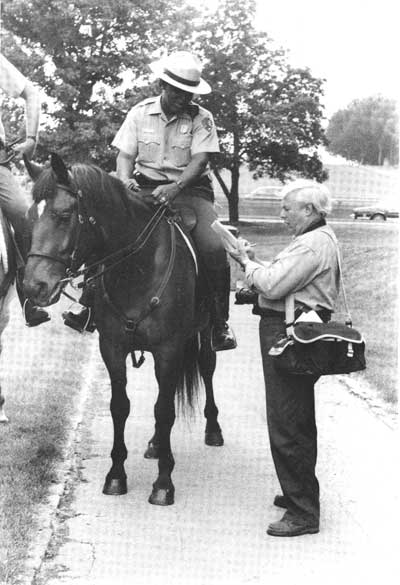

| Ranger Cortez Holloway speaks to a member of the press from horseback, 1991. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

The role of the Division of Law Enforcement and Safety at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (JEFF) evolved dramatically during the 1980s, expanding from a neglected and under-utilized function to a major component of park operations.

In the late 1970s, the "Protection Division" at JEFF was small and its duties were limited to the role of security guards. Ivan Tolley was brought to JEFF from Isle Royale as the Chief Ranger in 1979. "Jerry Schober created the position for me," recalled Tolley. "When I arrived there were five guards, GS-5s, unarmed, all working under the chief of interpretation. There was no funding of us as a protection division — all the money came from other divisions." [1] A report by the Regional law enforcement specialist in 1980 noted that of 150 employees at the park, only four were involved in protection, and they were usually kept busy with other duties. The report went on to say:

A review of criminal activity at JEFF indicates a need to improve our visitor protection program. The Superintendent and his staff realize that criminal activity is a problem that has to be dealt with, and have taken steps to reorganize the protection division. Although this step has been taken, the process will take some time before the program is in effect. In the meantime, criminal activity is increasingly taking its toll on visitors in the park. . . . [2]

|

| Chief Ranger Ivan Tolley, June 29, 1984. Photo courtesy John Weddle. |

The Arch is located in a downtown, highly-urbanized, metropolitan area. Its landscaping projects include shrubbery, trees, reflecting pools, etc. Criminal activity found in this type of urban setting will continue to be prevalent within the boundaries of the park unless we make a firm commitment to provide the quality of protection necessary to establish and control the activity that occurs in the park. Crime prevention will require higher visibility of protection personnel operating with professional guidance within a well-designed visitor protection program. . . .

The park is under proprietary jurisdiction and the St. Louis Police Department has the authority, but not the primary responsibility, to enforce laws within the park. . . .

Our rapport with the City Police is good; however, they are also restricted because of limited manpower and budget restraints. . . .

Our experience with contract protection (guards) left much to be desired. This is due mainly to the qualifications of personnel found on most guard forces. Usually personnel are given minimal training and the standards are expected to be low. In general, guards are not law enforcement officers and their response to criminal activity is usually limited to notifying the professional officer. The cost of this limited service is high and would not be appropriate for the needs at JEFF. [3]

The combination of large numbers of visitors and an urban environment resulted in a situation far beyond the capabilities of four protection rangers. Few of the rangers had law enforcement training. A ranger spent the night in the Old Courthouse, traveling from key station to key station with a security clock. Chief Ranger Deryl Stone [4] assessed the situation in a 1992 interview:

When anything [happened] other than a drunk or a derelict who had to be escorted out of the park — if they had any criminal activity, in other words — they notified the city police department, and they came down and handled it. The stolen cars were all handled through the city police. At a time in the early '80s, we had a significant number of stolen cars, and that was before the Arch parking garage [was built, when an open lot was located in the same area]. [5]

To deal with this situation, the protection division was reorganized, additional employees were hired and given expanded duties. Approximately 20 positions were filled in 1981 and 1982. By April 1982, 24-hour per day coverage was being provided by protection rangers, and modern surveillance techniques were being employed. [6] Funding for these changes often came at the expense of other park functions, but park management considered the need great enough to warrant a redistribution of monies. [7] A 1982 Operations Evaluation praised the direction in which law enforcement was moving at JEFF:

The Supervisory Park Ranger, Division of Protection and Safety [Ivan Tolley], is to be commended for his development of a highly professional organization that has, in the past year, grown to a 24-hour per day operation utilizing modern surveillance techniques to monitor the museum structure for illegal activity. This organizational development would not have been possible without the support of park management in general. [8]

Chief Ranger Deryl Stone said of Ivan Tolley:

Ivan was a very dynamic, aggressive person, and, by hook or crook, forced the changes to be made; he mandated it, demanded it. . . Ivan was the moving force who brought this park into the twentieth century. [9]

Concurrent jurisdiction was ceded to the United States Government for Jefferson National Expansion Memorial by Missouri House Bill 1768, signed into law on June 16, 1982 and accepted by the director of the National Park Service on February 3, 1983. [10] This meant that JEFF was given the primary responsibility for the protection of the grounds, buildings, and visitors to the Memorial. Chief Ranger Stone outlined the need for the Park Service, at JEFF, to maintain a professional law enforcement staff of their own:

First, our true park visitor . . . has the expectation of seeing, meeting and dealing with National Park Service employees, in this case rangers. The second reason is the mentality of the enforcement person. A city police officer is a city police officer. He's a cop, he thinks like a cop, he acts like a cop. We're not saying that is bad, however we do have somewhat of a different style, a different philosophy in dealing with people. No matter what we find them doing, within parameters, we treat them as a park visitor, with the "Yes, sirs" and No, sirs" and the "Yes, Ma'am" and "No, Ma'am." . . . So I think that it's important that we maintain the Park Ranger image, and that we do it by performing the law enforcement ourselves. If we had the city doing all of the law enforcement here we would have 95% reactive law enforcement. That means they would come when they were called, only when something went wrong. [11]

|

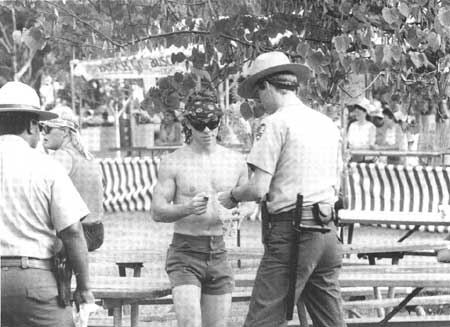

| Park Rangers issue a warning at the VP Fair. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Although the protection staff was expanded, criminal activity continued on the grounds of the Gateway Arch, especially after dark. Reports of these crimes in the local newspapers made the Arch seem like an unsafe place, and represented the highest form of negative publicity. [12] By 1985, the total division staff numbered 18, with five people working each of the three shifts. Two GS-6 Lead Park Rangers were chosen, and seven employees were certified as Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs). Ivan Tolley was again commended for his development of a highly professional team. [13]

A new law enforcement responsibility for the protection division began in May 1986 with the opening of the parking garage on the grounds. Coverage was provided on a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week basis. [14] It was not a task which the division was prepared to handle. "We were naive about the impact of the garage on our operation," recalled Criminal Investigator John Weddle. "We were in no way prepared, staff-wise or support facilities-wise, to handle what we got. Within the first 12 or 14 days of the opening, there were several major felonies committed. We had no training, and no computer tie with other law enforcement agencies." [15]

In addition to the new garage, the division handled approximately 200 special events that year, ranging in size from small press conferences to weddings, dinners, banquets, and the 1985 World Series Party sponsored by Anheuser-Busch, with approximately 1,500 people including sports and TV personalities. Missouri Governor John Ashcroft, U.S. Attorney General Edwin Meese, FBI Director William Webster, and foreign dignitaries attended events in the park, and were protected by the division. [16] Growing drug-related problems were noted on the grounds, and Ivan Tolley remarked that "drug-related crime has increased 10-12 fold this year." Additional staffing, over and above the 1986 increases, was requested to adequately patrol the grounds. [17] The division staff increased to 21 employees during 1986, including a division secretary; 10 employees were qualified EMTs. [18] A REJIS (Regional Justice Informational Service) computer terminal was installed in the fall of 1986, and the park's operations center was created. [19]

In 1987, the division was decimated by the coincidental transfers, resignations, and terminations of staff members, reducing the force to nine law enforcement officers and the chief. With no replacements forthcoming, JEFF experienced the worst criminal activity of the decade during calendar year 1987. [20]

In a move prompted by the Midwest Regional Office, designed to enhance JEFF's operation, the Division of Visitor and Resource Protection underwent a major reorganization in October 1987, which nearly doubled the number of commissioned law enforcement rangers. Twelve new employees were hired and four patrol teams were created. A major reason for this expansion was to more adequately cover the Arch Parking Garage on the Gateway Arch grounds. Supervisory positions were established for the operations center and for the two additional patrol teams, and the lead Park Ranger positions were abolished. With the increased staff and patrolling activity, a decrease in the number of larceny and robbery incidents was recorded, accompanied by a 300% increase in written warnings, citations, and arrests. This trend continued during the last three years of the 1980s. [21]

In 1988, for the second year in a row, crime statistics decreased, primarily because of the increased staff and revised patrol procedures. Arrests were up, as were citations. This was due in large part to an emphasis on larceny and robbery suspects coupled with the REJIS/NCIC terminal, which was the major factor enabling such arrests. [22] Chief Ranger Stone elaborated:

Give me a person's name, and I can start a background check on warrants. The more information you give to me on them, the more I can find out about them in almost no time flat. . . Anyone encountered in a law enforcement mode, we run a check for wants and warrants. Last year [1991] alone we arrested 98 people on outstanding warrants from other jurisdictions. So far this year, (we still have 2-1/2 months to go this year), we have arrested over 140 people on other people's, (other jurisdiction's) warrants. Probably 70% of them are insignificant, but we've so far arrested people on warrants for bank robbery, murder, rape, and narcotics. [23]

On June 2, 1989, Ivan Tolley retired as chief ranger of the Visitor and Resource Protection Division. Supervisory Park Ranger Deryl B. Stone transferred to JEFF from Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore on June 6, 1989, as division chief. [24] He recalled:

When I came here, in '89, [Jerry] Schober was Superintendent, [Gary] Easton was Assistant Superintendent. We sat down and they said, "It's your division, you do what you need to do, get it so it is your operation." . . .

The original name when I came here was the Division of Visitor and Resource Protection. I didn't feel that adequately identified what we were or who we were at that time, or what we were going to become. So I asked for the name change to the Division of Law Enforcement and Safety. Those are the two primary functions of my division . . .

Chief Ranger Deryl Stone (center, with glasses), flanked by St. Louis city police officers and Park Rangers Chuck Carlson, Keith Temple and Chris Cessna. NPS photo by Al Bilger, courtesy Division of Law Enforcement and Safety. One of the things that I felt was going to be needed here because of the size of the park and the number of the safety-related items we had and visitor injuries, was a safety officer. Also, we had a law enforcement specialist in the 025 series, and I thought that was inappropriate, that what we really needed was a criminal investigator in the 1811 series criminal investigation division, so we reorganized it. . . . [25]

Chief Stone changed the structure of the working shifts in his division:

When I came on we were on a two-team concept [in place from January 1989], a day shift and a night shift. Each shift is responsible for all their coverage, so you'll have people coming in early, people coming in mid-shift, etc . . . We may someday go over to the three-team concept, especially when we get East St. Louis, but right now the two-team concept works. Instead of having the supervisors in charge of a district, like you'd have in a traditional park, the supervisory rangers here are in charge of a time frame [day shift or night shift]. . . . The team that's on nights right now will be on nights for four months, and every four months they rotate between day shift and night shift, the entire team shifts over. We've done it that way, on a four month's time frame, so you're not always going to be at the same time of the year on the day shift or the night shift. . . Our transition is also set up to coincide with the semesters at the local colleges here, so if the person was on night shift and they wanted to take some day classes at college, they could, or [vice-versa], . . . and continue with their education without having to go through great contortions to manage their schedule around their school schedule. . . I think that's something that's originated here. I don't know of any other parks that have the same set-up as far as days and nights as we do, and I think this is the only park that has tried to set it up so that we could coordinate with the college system. They may do it [at other parks] on a one-person basis for special needs, but we've tried to do it here across the board for everybody. [26]

Safety

In 1990, a great deal of progress was made in the areas of safety and fire prevention due to the new fire/safety officer position. The position was created in response to the unique character of the Arch and its concentrated area of visitation, and as a result of NPS safety and OSHA regulations, which were becoming more complex. The park's Documented Safety Program was rewritten and a "Safety Awards Program" developed. To comply with OSHA standards, all 175 fire extinguishers in the park were replaced. Emergency exit maps were installed throughout the Old Courthouse to facilitate evacuations. [27]

Shortly after his arrival, Chief Stone identified the presence of hazardous asbestos material in the Gateway Arch complex. Prior to the removal of the asbestos-containing material from the ceiling at the Arch entrance and the tram load zones in 1990, extensive air quality monitoring was conducted. The testing showed that the park had not reached the maximum allowable limits of asbestos fiber in the air sampled. Samples were taken in both public and non-public areas of the Arch complex. [28]

All of the park's Emergency Operations Plans were rewritten during 1990. This was due, at least in part, to a heightened awareness of the potential for a major earthquake in the area, caused by predictions of such a disaster played up by the media. While the earthquake along the New Madrid Fault did not occur in November 1990, the Division of Law Enforcement and Safety took necessary precautions, such as purchasing and stockpiling emergency supplies and materials to provide for at least 50 people for three days. Two cellular phones were also acquired for emergency communications. Every member of the park's staff attended one of the four two-hour emergency earthquake preparedness training sessions. [29]

Chief Ranger Deryl Stone commented on the revamping of the Emergency Operations Plans (EOPs):

There had never been any EOPs done up until about '86, '87. They just kind of slogged along and dealt with things as they came up, and then of course the system started mandating emergency operations plans, emergency evacuation plans. . . We've taken the earlier ones and refined them even more, and of course now having a staff specialist, a safety officer, he's [made] those into a lot more useful tools, taking out the bureaucratic things and [making them] flexible for the future. [30]

Emergency Medical Services System

In 1986, the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) system was implemented at JEFF. A coordinating doctor was responsible for park activities, and Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) were on duty at all times. Half of the law enforcement staff were required to be qualified Emergency Medical Technicians; the other half were First Responders. The other divisions helped with the responsibility by training First Responders as well. The majority of the interpretive staff were CPR qualified, due to possible health emergencies at the top of the Arch. The division worked closely with the city EMS to coordinate emergency plans for such situations. [31]

Emergency preparedness proved invaluable on several occasions. At the 1990 VP Fair, for example, two rangers provided emergency CPR to a heat victim and were credited with saving her life. Each ranger was awarded the National Park Service's "Exemplary Act Award." [32]

Hazardous Duty

The duties of a law enforcement ranger were difficult and sometimes dangerous. This was especially true in an urban area such as St. Louis, where violent crimes continued to escalate during the 1980s. One of JEFF's law enforcement rangers was assaulted on the grounds during 1990 with a dangerous weapon, a Ninja Key Ring. The ranger received numerous cuts, puncture wounds, contusions and abrasions, which affected his ability to make the arrest. The weapon used was featured in the "Unusual Weapon" section of the FBI's monthly bulletin, from information submitted to them by JEFF. [33] The first protective vests were purchased for law enforcement personnel in 1986, and all law enforcement rangers had vests by 1990. [34] A request from Chief Ranger Stone to allow law enforcement personnel to carry their weapons off duty was denied by Superintendent Schober, although Stone himself retained this privilege. [35]

On July 1, 1991, three cars of a 77-car train derailed 100 feet above the ground on an overhead approach to the Mississippi River, just south of the park. Since the cars of this freight train contained potentially lethal chemicals, the St. Louis Fire Department requested that the Arch, museum, and grounds be evacuated. One of the derailed tank cars was empty, but contained 3% propane (an extremely explosive mixture), and the three cars just ahead of the derailed cars were each filled with 16,000 gallons of Nitric Acid, and were in danger of falling from the trestle. The Incident Command System was implemented, and an estimated 7,000 people (visitors and non-essential employees) were evacuated from the Gateway Arch, museum, and grounds in an orderly and efficient manner. The park and surrounding areas remained closed for 2-1/2 hours, until the hazard was mitigated, before visitors were allowed to return. [36]

Law Enforcement activities increased in 1991 over the previous year, with 95 persons arrested for outstanding warrants from other jurisdictions. A total of eight robberies occurred within the park, five with firearms, and one with a knife. Drug incidents doubled to 44 cases, with $10,546 in drugs seized. DUI arrests also nearly doubled from the previous year. Twenty-eight drunk driving arrests were made, and an increase was noted in the possession of weapons such as guns, knives, brass knuckles, and clubs. [37]

The VP Fair

A major responsibility of the Division of Law Enforcement and Safety during the decade was assuring visitor protection at the annual Veiled Prophet Fairs. Ivan Tolley was initially opposed to the idea. "I thought it was a travesty. It's not the kind of place for that kind of event. It was set up poorly, and very hard to get VIPs and support systems in and out. The traffic situation was very bad. It also led to friction among the staff." [38] Because of the size of the crowds, the JEFF staff was supplemented each year by Special Event Teams (SET) from other parks. In 1985, for instance, seven teams representing the Western Region, the Southwest Region, the Rocky Mountain Region, the Midwest Region, the Southeast Region, and the U.S. Park Police provided assistance. [39]

Chief Ranger Stone assessed the participation of the Law Enforcement Division in the VP Fairs in this manner:

They started professionalizing [the Regional SET teams] here with the onset of the VP Fairs on the grounds. They started bringing in commissioned rangers from other areas, and taking more of an active part in the law enforcement activities.

For the earliest fairs, I think for the first three fairs, they had no prohibition of bringing in alcohol. You could either buy it here, or you could bring it on. . . . Minor drinking ran rampant. Chaos led to pandemonium. . . . It was more like the meeting of the Friday night knife and gun club . . . because there were lots of fights. Each year the VP Fair was, I think through the efforts of the police department, the National Park Service, and the VP [Fair Foundation], organized in a more orderly fashion and became more of a family affair. . . .

Last year, on the end of the VP Fair critique, one of the special event team members said that the fair was not nearly as much fun as it was in the formative years, because [during] the last two fairs he had never pulled his nightstick out once, and had not broken up any fight larger than two people, where in the formative years, you would have thirty to thirty-five combatants going at it at one time. So, they said it's getting awfully dull, and awfully routine. Now, dull and routine is fine, but when you look at the number of people we have here during the VP Fair, there's always the potential for something, so we [must] maintain a high-level presence . . .

SET team rangers at the VP Fair. Courtesy John Weddle. We use four special events teams, with seven persons per team. Three midwest special events teams, plus one special event team from another region. . . . We bring them on before the fair, stagger them in, then have all four of them on during the fair, then stagger them back out, so we have people here during set-up and during take-down, plus we have the maximum available during the fair itself. My staff goes on two weeks of 12 hours on and 12 hours off. We have a team that covers from 11 a.m. until 11 p.m., and then the other team comes from 11 p.m. until 11 a.m. John Weddle acts as Deputy Incident Commander, and runs the park from 11 at night to 11 in the morning, while I get it from 11 in the morning until 11 at night.

The first year I was here [1989], we had some St. Louis Police Department people working on a secondary detail. They were off-duty, but were in uniform, and were being paid by the VP Foundation, instead of one of my SET teams. Again this year, we hired off-duty police officers, to replace one of the special events teams, ostensively because it's a little less expensive to hire them, even though their overtime rate's a little bit higher, but they don't have to pay travel and per diem for a team while they're in here. The rationale was that we could hire city policemen . . . [and] we would form some lasting friendships and build a camaraderie between the National Park Service patrol officers and the city police. In theory it sounds outstanding. In reality we had some problems with it. . . . They have a reactive mentality, and that is, stand off to the side, wait for something to happen, and then go up and get in the middle of it. Our way of doing it is, if it looks like something is going to occur, we go get in the middle of it before it occurs, and most times we can prevent it, instead of cleaning up after it. [40]

The dispatch center under the Gateway Arch. Courtesy John Weddle. People think that the VP [Fair Foundation] is getting quite a bargain, and I guess in some ways they are. They pay for the transportation of the special events teams, they pay for the per diem for the special event team members, they pay for all the overtime for my folks working above eight hours, and they pay for the command staff that stay downtown for the fair. The National Park Service, however, pays the basic eight hours of all of our employee's salaries; only overtime is paid for by the VP Fair.

The work of putting on a fair starts out the day after the fair is over, that's when the planning starts for the next year's fair. So we're never out of the fair mode . . . . It's a long, arduous grind, and of course it gets more and more chaotic the closer the fair gets. . . .

We escort, or assure the safety, of getting the entertainers onto and off the grounds. Once they're in the safety of the compound and the stage, there's city police and security in there . . . At times we get them in and out in vans, and other times on foot, because there was no way to get them on the grounds in a vehicle. So we had to walk them on, which gets your pulse rate going a little bit higher. When you're walking with . . . Willie Nelson and Waylon [Jennings], and they've got a bunch of rowdy fans that all want to come up and touch them and you're trying to keep the crowd back and keep these people moving, it gets kind of interesting . . . . [41]

Rank Identification at the VP Fair

At my first VP fair [1989], we had some problems with some of the city officers that did not know . . . who we were as far as our rank structure. I had a few of my senior staff being told off by patrolmen from the city. And so the next year I had my staff go out and buy [military] shoulder or collar insignias . . . I bought "bird colonel" insignias. I did not like that at all, and ended up buying insignias that simply say "chief" in gold on them that I wear on my collar. John Weddle, my criminal investigator, is the principal second-in-command, and I had him wear captain's bars. My shift supervisors wear lieutenant's bars, and the senior park rangers and SET team leaders wear sergeant's chevrons. When we started wearing rank insignia, attitudes changed and the police department's understanding of us changed, because now we had something that they could visually see that equated to their rank structure. This "everybody wears the same uniform" didn't make any sense to them.

So we thought that [wearing visible rank insignia] was important here, and we've done it. We still wear them on specific occasions; if it's going to be a meeting with outside agencies or anybody else, we go ahead and wear them. Or when we have something special on the grounds where we have other agencies coming on, we wear them. Now, there is some consideration [in the Park Service] . . . of starting to authorize officially the rank insignia, because they see the benefits of it. [42]

Arch Parking Garage

Chief Ranger Stone assessed the division's role in maintaining protection for and a Park Service presence in the Arch Parking Garage:

[When] the parking garage opened, [the Bi-State Development Agency] paid for part of the Law Enforcement and Safety Division's ranger's salaries. They pay for seven positions, plus part of our NCIC Law Enforcement computer system. Basically, it's on a donation basis; they reimburse us each quarter for that expenditure for that time. And it's done on a budget, so I know how much I can spend. [43]

From the outset, the Bi-State Development Agency and the National Park Service agreed that a law enforcement ranger would be on duty in the parking garage at all times. They especially wanted to avoid the problems that had occurred in the open parking lot on the north end of the grounds, which preceded the garage. These problems included a high rate of stolen cars. Constant surveillance of the garage reduced this number to zero, and decreased breaking and entering into cars dramatically. Chief Ranger Stone continued:

Although our agreement calls for one-person, 24-hour-per-day coverage, in reality we have more than that in the garage, because of the proximity of Laclede's Landing. [44] [The Garage] is a very popular parking place for people going to Laclede's Landing because it offers undercover, sheltered parking, and . . . protection for their vehicle and their property. . .

[In the beginning on] a Friday night they would have one, maybe two rangers in the parking garage. The next day it would take the Bi-State folks maybe half a day to clean up the broken glass, the beer cans and all the litter in there. We've taken a very aggressive stance on that sort of stuff. If you break a bottle, throw a beer can out the window, we will cite you for littering. If you drive in that garage drunk or impaired, we will stop you. . . . We have prosecuted people that we have found breaking into cars. We try to maximize law enforcement to make it a very safe family environment, and by and large the greatest majority of people that are repeat visitors on weekend nights are appreciative of seeing us out there.

We have had some identity problems doing law enforcement, especially in the Arch Parking Garage, because [local residents] perceive the only people who are going to do law enforcement in downtown St. Louis are blue-uniformed city policemen. When we come up and have to take an enforcement action, the first thing out of their mouth is, "You can't do anything to me, 'cause you're a security guard!" Well, we endeavor to explain to them that we are not security guards, and by the time we get them down to the city jail, which we use as a holding facility, and the sergeant down there explains that we are Federal Officers, then it starts dawning on them, but it takes quite a while.

The interesting thing about that parking garage is our single largest law enforcement problem is under the refuse and sanitation section of 36 CFR, and that is public urination. When they built the parking garage they purposely did not put any bathrooms in there, because it is my understanding that they felt bathrooms draw undesirables. I think what they were saying without saying it is that they did not want public bathrooms where they might have sexual activity going on. Our biggest single ticket is public urination, and we issue a dozen of them a week. They go over to the Landing, drink copious amounts of beer, walk back to the car, and by the time they get in the parking garage they have got to go to the bathroom. And so they just stand there and look around, and urinate right there. And 20% of the violation notices are issued to females. . . So that's our biggest single problem . . . We're not talking about bums, but people driving new Trans Ams and all, this is an upper middle-class, young group going over there.

Anyhow, the Parking Garage has been a real asset, it takes up less space and it's less visually obtrusive than the old parking lot up there, it has created some additional paid park ranger jobs here. . . We have the high visibility; we want to be seen, we want to prevent things from occurring vs. investigating them after they occur. [45]

The Staff

The Division of Law Enforcement and Safety has maintained an average staff size of 26 people by 1990, divided between the Chief Ranger's Office, Operations Center, and Patrol sections. [46] In a 1992 interview, Chief Ranger Deryl Stone discussed the evolution of the staff during the 1980s:

I don't think many people appreciate the number of rangers that come and go through this park. We are . . . one of the "back doors" into the [National Park Service]. We hire off the OPM register, we have a large number of [permanent] GS-5 rangers, and our job is year-round, so we don't have any seasonals. The vast majority [of people we bring into these jobs] have four-year college degrees, and have two to four years of Park Service experience elsewhere. So they come here, not because they are enamored with St. Louis or westward expansion, or the Arch itself, but because it's a way into the Park Service.

Initially when they started coming in, the first thing that was done was they were sent to FLETC, the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center . . . As soon as they got done with FLETC, that made them very desirable for other parks to hire, and they were coming and going at a too rapid a rate. What I've done now is, when we hire a person they must have their seasonal commission. We make them wait their full year probationary period, using only their seasonal commission, and then send them to FLETC, understanding once they come back from FLETC they're going to be here less than six months. So at least I've gotten one full year out of them before they go to a traditional National Park where they wanted to be in the first place.

Our constant turnover of personnel creates some problems; but also we do things right here. We instill some good things into the rangers so that when they leave here we hear good reports from the parks they go to. I've heard chief rangers say that the rest of the rangers in their park are mad at me because [a former JEFF] ranger came in and writes such good reports that that's going to be the new standard, and so that gives us a little pride here. . . We also give them enough experience in a year and a half or two years here in an urban area, that when they go to a smaller or more traditional park where there is less activity, what those small parks think is a major crisis was a day-to-day activity here, and it doesn't get the ranger flustered at all. He's dealt with the VP Fair. When Waylon and Willie were onstage and we had 250,000 people out in the audience, that's pretty intimidating. If you go to a traditional park and see what they consider hectic and crazy, that's nothing compared to what they've seen here. So they're better equipped to deal with whatever might come along in a career. The rangers here are sought after and almost every one of them has left here going to a GS-7 promotion. So that says a lot about our operation, I think. [47]

The Gulf War

In early 1991, the Division of Law Enforcement and Safety had to respond to a rather unique situation. When the United States went to war with Iraq in January, there was a reasonable potential for terrorist attacks against official federal government facilities. The national parks, as some of the most visible of these areas, were likely targets. In response, many national park areas began taking special precautions. At JEFF, these took the form of limiting access to the Old Courthouse and the Arch visitor center, and monitoring visitors as they came in. Pro- and anti-war activists were issued permits for small demonstrations on the grounds. Special "Law and Order Funding" was used to support the increase in security during the Gulf War. [48] Chief Ranger Stone recalled:

When the Gulf situation started warming up, shortly after Iraq invaded . . . Kuwait, we anticipated that there was going to be some kind of response by the U.S. or a coalition, and we started looking at security here at the Arch. I had a meeting with the SWAT team coordinator for the City of St. Louis, and we jointly looked over the Arch, the facilities, and the site. . .

Just prior to . . . Desert Shield going to Desert Storm, we had a meeting with the FBI, talking about a scenario of what could happen here. It was decided that sabotage by Middle Eastern covert operations was a minimal concern; however, one of the concerns was a takeover by either anti-war factions, similar to what we saw during Vietnam, or by Middle Eastern factions trying to make a political statement. It was determined that if someone ever got into the top of the Arch, and barricaded themselves in, that it would be almost impossible to get them out. High profile protests such as hanging banners from the Arch just made everybody shudder.

We had some basic contingency plans set up, and the minute the air war started over there, we applied for emergency law and order money, and ordered hand-held magnetometers, along with walk-through magnetometers. We got the hand-held magnetometers very quickly. We were back-ordered on the walk-through magnetometers, but got the U.S. Park Police to provide us with one, and a Park Police operator, and got him out here for the first three weeks of the Desert Storm operation. At that time they were removing asbestos from the ceiling of the Arch [Visitor Center], so we were able have one side of the Arch completely closed off, ramps and everything, so luckily we had . . . a controlled entrance at one point. Anybody that came into the Arch initially was magnetometered by hand, women's purses were checked. After about three weeks we got our shipment of walk-through magnetometers. . . . We had the cooperation of the interpretive division, who primarily did the screening of the purses, [49] and the commissioned law enforcement rangers did the walk-through magnetometer, the secondary checking, and the checking for weapons. Surprisingly, we had no visitor complaints about the security system. It seemed to be one of those things that they took in stride. The ones that never even asked why were the Europeans. Of course, the Europeans are very used to a higher level of security that we have here, going into anyplace. They didn't even realize that we had gone to a higher level of security. We had a number of people that started down the ramp, saw the magnetometers, and turned around and left. We did not follow them out of the building, that was their choice, we don't know why they turned around. However, we have a pretty good idea. We made some 20 narcotics cases during that time frame. People walked through the magnetometer with brass, one-hit bongs or pipes on them, or narcotics wrapped up in aluminum foil. We also ended up with several people walking through the magnetometer with guns, and knives, and brass knuckles. . . . One lady walked through with a six-shot .22 pistol, and she thought "Oh, it's a small gun so it won't register."

We continued on with the magnetometer operation for an extended period of time, until the ground war ended. . . . We spent around $60,000 on overtime. . . But it was all covered out of Washington on special law and order account money, because the FBI felt that here in the Midwest we were high profile. I did a lot of talking with my counterpart at the Statue of Liberty. They were looking at the same scenario there, and went to a much higher profile.

This was a situation that I looked at myself, thinking about my experience in the Park Service, about working special law enforcement details at Ellis Island, and at the Statue, at potential takeover times. I took my concerns to the Superintendent and Assistant Superintendent, laid out where we were at, what I thought we needed to do, and got 100% support from them. I took it to Region, . . . and they felt that we were the highest threat in the whole region. You know, taking over Perry's Victory to make a political statement didn't seem to be very high on anybody's list, but taking over the Arch did, so they concurred, and we went in for the special funding. [50]

These measures remained in effect until March 15, 1991, after the Gulf War had ended. On March 14, Chief Stone met with Bill Frances, agent-in-charge of the domestic section of the St. Louis Field Office of the FBI, and advised Superintendent Schober:

We discussed our continued operations of screening visitors by way of the magnetometers (metal detectors). Agent Frances advised that activities in the local Arab-American community are non-existent and no known threats exist at this time. He felt that there was "no compelling reason to continue the high level for security" which we implemented at the start of Operation Desert Storm.

It is also my recommendation that we discontinue the use of magnetometers at this time, however, all law enforcement personnel will continue to be extra observant for any unusual activities or suspicious persons. [51]

The magnetometers were taken out and the experience of visiting the Gateway Arch returned to normal. The lessons learned from this successful high-level security experience were ones which will hopefully never again have to be employed, but they were tested and seem to work. If high-security screening of visitors is again needed, the division would be able to implement proper measures quickly and efficiently. [52]

Dispatch

The dispatch operation grew and became more professionalized during the course of the 1980s. The dispatch center, located in the Gateway Arch complex, served as the information center for the park. It was a safety lifeline for the rangers. "If they have a problem dispatch can get help out to them right away, whether it be our own people or additional city police," Chief Stone elaborated. "They also are the emergency incoming line, that answer the telephone calls coming into the Arch. They monitor the closed-circuit television system that covers the inside of the Arch itself both day and night, as well as the intrusion and fire alarm systems for grounds maintenance, the Old Courthouse, and now for the Ulysses S. Grant site. The dispatch center is not a very glamorous job, fairly low paying at GS-4, and yet really at the heart of our operation. Without them, I'm sure the people would have a lot less enthusiasm to go out and do their job, knowing that they didn't have the backup." [53]

Horse Patrol

Planning began in 1991 to implement a horse-mounted law enforcement program at JEFF. The program was designed to reinforce the image of the National Park Service as horse-mounted rangers, and to increase visitor and resource protection. The ability to respond to law enforcement or emergency situations quickly was increased by the ability of the horse-mounted rangers to travel throughout the open area of the 91-acre Gateway Arch grounds, rather than being limited to the park's sidewalks and roads as in vehicle patrols of the same area. [54]

Three horses were transferred to JEFF by the U.S. Park Police in Washington, D.C., and the program was in place by July 2, 1992. "By removing some of our law enforcement rangers from the marked vehicle they traditionally use for patrol and putting them on a horse we make them more visible and more accessible to the public in general, and our visitors in particular," said Superintendent Gary Easton. The horses were stabled at the St. Louis Carriage Company, which ran horse and carriage tours of the downtown area, a convenient six blocks from the park. [55] Chief Ranger Stone described the program with obvious pride:

We developed the horse patrol here for several reasons. One is recognition and approachability. . . You put a ranger or a city policeman on a horse, the only thing you have to worry about is getting stepped on by all the people running over to pet the horse and talk to the ranger. And so, public relations was one of our goals, and that's been an overwhelming success. Number two is just visibility. We have bad guys. They can see our ranger. He sits tall in the saddle, he can be seen at a great distance. So this is a visual deterrent to crime. And mobility; the ranger is extremely mobile. So we've accomplished everything that we set out to do by having the horses, and they're extremely popular. [56]

|

| The horse patrol at JEFF, 1991; Keith Temple, Cortez Holloway, Todd Roeder. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

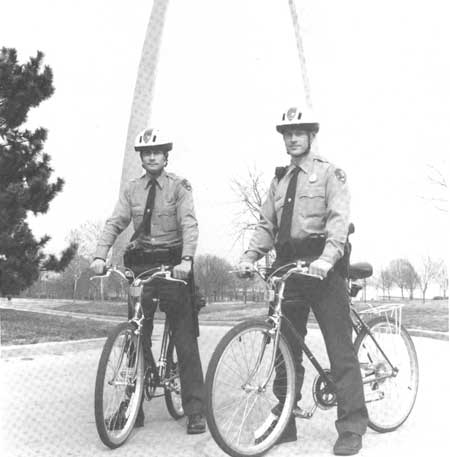

Bicycle Patrol

A "Bicycle Patrol Program" was initiated in 1991, using two mountain bikes found chained to park trees and never claimed. Patrolling on mountain bikes was not only fast, but an effective mode of transportation on the Gateway Arch grounds, and environmentally sound. The park received very positive reactions from the public regarding the bike patrol program. [57] Chief Stone commented:

[In the Fall of 1991] I had a couple of enthusiastic young rangers come up and suggest that we start a mountain bike patrol on the grounds, not as a total separate unit, but as part of the operation. Right now we have a patrol car that is primarily used for the transportation of prisoners. We have a four-wheel gas patrol Cushman, and we have an electric cart that's used in the garage itself for moving around in there. But they felt that so much of the grounds patrol is being done on foot, and that it takes so long to respond from any point, that they needed to have a little faster mode of transportation, and also one that was a little more environmentally conscious. So I said that I would be open to it. Immediately they found two mountain bikes that we had stored in our lost and stolen property section. They were unclaimed property, and so Ranger Jim Hjelmgren wrote an SOP, and we came up with a usable plan, using the Las Vegas and Seattle models. The only change in uniform was that you could wear a black athletic type shoe vs. our standard dress uniform shoe. You needed to wear the rest of the dress uniform, and a pants clip for your pant leg.

Instead of being on foot patrol, the ranger has the option of doing the same thing on a mountain bike. The visitors find the rangers much more approachable, have some common ground to start a conversation with, and seeing them on a bicycle makes them a little more human, a little more approachable. Not quite as approachable as a horse patrolman, because they can't pet the bicycle, but at least it does make them a little more approachable. Also it's a much quicker form of transportation for the ranger, and also very quiet compared to the gas Cushmans running around, polluting the air with gas fumes.

Violators are not attuned to seeing anybody in law enforcement approaching on a bike, and they never even give a bike a second glance. We've made quite a few narcotics cases with the bicycle. The patrolman rides right up onto a group using illegal substances and . . . takes appropriate action. So it's been well-received, it's done a good job here. . . . A couple of the other parks have used mountain bikes, but for more traditional uses, search and rescue on trails and that sort of stuff, where we've used them here in an urban setting. They've worked out very well for us.

I think that the mountain bike patrol and the horse patrol in an urban area sets the stage for our park being one of those that is willing to do whatever we need to do to get the job done in an urban setting, doing less-than-traditional things. The administration here has always been willing to accept changes very readily, to try new things to get the job done. And it's exciting to be in that kind of a park. [58]

During little more than a decade, the Division of Law Enforcement and Safety grew from a staff of four security guards to a "round the clock," professional law enforcement operation, deterring crime in an increasingly complex urban environment. It is a credit to Ivan Tolley, and the foresight of park management, that the division was expanded and revamped when change was needed. Deryl Stone continued this process, modernizing and streamlining the operation enlarged by Tolley. The division was transformed from a staff which was dependant on outside law enforcement agencies to one which was self-sufficient and capable of handling huge events, natural disasters, and heightened security situations.

|

| Mark Thompson and Jim Hjelmgren on bicycle patrol at JEFF, 1991. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

jeff/adhi/chap10-2.htm

Last Updated: 15-Jan-2004