|

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

Administrative History |

|

|

Administrative History Bob Moore |

CHAPTER NINE:

Museum Services and Interpretation

|

| A young visitor touches history in the person of a life-sized statue of Thomas Jefferson at the entrance to the Museum of Westward Expansion. Visitors were originally encouraged to touch the statue as an interpretive experience; this was later discouraged as a conservation measure. NPS photo by Joseph Matthews, April 1978. |

The number and complexity of the interpretive themes at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (JEFF) have posed a challenge to managers, historians, and interpretive rangers since the creation of the park. The Memorial is dedicated to the entire sweep of western history during the 19th century, and also focuses on life in St. Louis, the slavery issue at the Old Courthouse, as well as a rich history of its own involving the establishment of the Memorial and the building of the Gateway Arch. Throughout the years, the park staff has responded admirably to these challenges, and the result has been the development of a diverse and exciting interpretive program.

Shortly after the establishment of JEFF in 1935, proposals were made for two museums to interpret the country's westward expansion and the historic architecture of St. Louis. In the 1940s, historians at the Old Courthouse began conducting tours of the building and presenting talks on St. Louis and western history. A key component of the 1947 architectural competition was concerned with providing a means of interpreting the history of the American West, which the memorial was intended to commemorate. Eero Saarinen, in his winning design, included an outdoor arcade containing sculpture and paintings which would help tell the story of westward expansion; a campfire theater and a pioneer village for historical/interpretive purposes; and two above-ground museums. None of these aspects of the Memorial were realized due to lack of funding, but efforts to provide some sort of interpretation continued. Temporary exhibits, consisting primarily of dioramas produced by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), were opened in the Old Courthouse in the 1940s. [1]

As plans for the Memorial's development were altered and revised, it was decided to build a visitor center under the Gateway Arch which would include space for a single large museum dedicated to westward expansion. In the late 1950s, historians began working on research and exhibit plans for this underground museum, and by 1967, an interim exhibit gallery was opened in the visitor center lobby. Finally, in 1976, the long-awaited Museum of Westward Expansion was opened and became the primary interpretive feature of the park. [2]

Due to funding and support from the Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association (JNEHA), JEFF's interpretive division was supplemented by a staff of JNEHA park rangers. Dressed in brown uniforms similar in style to those of the National Park Service (NPS), this alternate "ranger corps" gradually took on a role which put JNEHA employees and NPS employees side by side, performing identical functions. In addition, JNEHA employees performed specialized duties, managing the park's audio-visual operations and the museum education program, under NPS supervision. This aspect of the interpretive division at JEFF was but one of many which made it a complex and unique operation within the NPS.

Interpretive Planning at JEFF

Interpretation at the Memorial received guidance from a variety of planning documents. The story of America's westward expansion was established as the primary interpretive theme, and with the addition of the Old Courthouse in 1940, St. Louis history and the building's involvement in the historic Dred Scott case were also emphasized. Park master plans in 1959 and 1962 identified appropriate interpretive activities, and the 1960 interpretive prospectus defined the objectives of the Memorial's projected interpretive features. In 1971, an interpretive prospectus for the Old Courthouse was completed. [3]

|

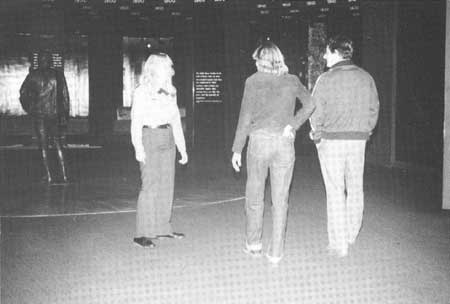

| Interpreter Lisa Hanfgarn greets visitors to the Museum of Westward Expansion, 1978. NPS photo. |

In 1981, the National Park Service mandated a new management document called the Annual Statement for Interpretation (SFI). The SFI was created to adequately address changes in individual interpretive programs, as well as record activities and accomplishments in each national park area's interpretive division. The initial Statements for Interpretation prepared at JEFF listed four specific interpretive themes: the vision of the United States as seen by Thomas Jefferson and other Americans in the early 19th century, which resulted in the territorial expansion of the U.S.; the settling of the West, made up of the daily life, experiences, and adventures of frontiersmen and pioneers who explored and populated the American West; the role of St. Louis as a base of operations and emporium for the trans-Mississippi West; and the architectural significance of the Gateway Arch and the Old Courthouse. [4] By 1987 two more sub-themes were added, which involved the history of St. Louis and the heritage of African-Americans, using the Dred Scott trials as a focus. [5]

Basic personal services described in the SFI during the 1980s included staffing the Museum of Westward Expansion through the use of both fixed stations and roving assignments; general public programs; museum education programs; staffing the visitor center information desk and the top of the Gateway Arch; orientation to and tours of the Old Courthouse; and special programs such as Storytelling and Black History Month. Among the non-personal services were publications such as the park newspaper Gateway Today, and orientation brochures for the Arch and Old Courthouse. The curatorial staff and a temporary exhibit staff were managed by the interpretive division chief as well. As the program grew, more services were added, including Victorian Christmas at the Old Courthouse; Boy and Girl Scout Days; the Union Station Urban Initiative; and the production of the informational handout, the Museum Gazette, primarily for in-house use. With the development of the Statement for Interpretation, the park gained a valuable tool for managing its interpretive program. [6]

Museum of Westward Expansion

From its inception, the Museum of Westward Expansion (MWE) was intended to take an approach which contrasted with that of traditional museums. The objective was to create a museum that would " . . . impress upon the visitor the drama of the West as a personal experience, to depict in powerful and compelling fashion just what it meant to be one of the Americans who went west in the years between 1803 and 1890." To achieve this goal it was decided that the interpretive story should focus on the ordinary people involved in westward expansion. "Events" or "famous figures" were introduced only to provide the necessary historical context. [7]

In 1960, as the construction of the Gateway Arch became a reality, Superintendent George B. Hartzog, Jr., began to focus on the requirements for a Museum of Westward Expansion. Without a specific plan, but with a vision for the future, Hartzog asked Saarinen Associates to design a huge, empty underground space into the Arch construction plans. Ten years later, Hartzog, then serving as Director of the National Park Service, selected Aram Mardirosian and the Potomac Group of Washington, D.C. to design a museum to fit within that space. Mardirosian was an architect, not a museum planner, and therefore "was not hindered by tradition and preconception." [8]

The challenges were considerable, since an exhibit plan had to be devised for a pre-existing space which was complicated by a uniform grid of pillars, necessary to support the roof and earth above. The problems of designing the museum included telling the entire story of westward expansion while omitting less important elements and avoiding the creation of a typical display of artifacts, graphics and labels. [9]

|

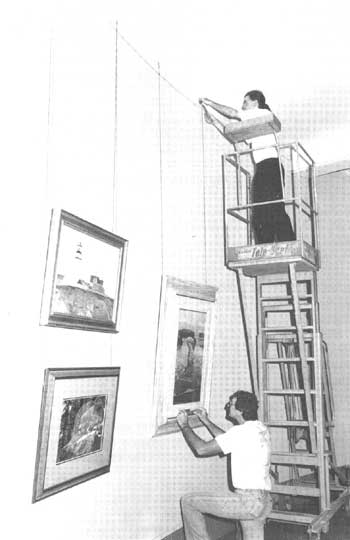

| Temporary exhibits on the American West were displayed in the Gateway Arch visitor center in the early 1970s. NPS photo. |

Funding for museum construction was provided in 1974 from several sources, including Federal appropriations from Congress; revenue generated by the Bi-State Development Agency's operation of the Gateway Arch transportation system; the City of St. Louis, which shared one-fourth of the development costs of the Memorial; the Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association; and the Memorial Parking Lot, operated for the National Park Service by the City of St. Louis.

Museum Contract Manager Frank Phillips, a 30-year veteran of the National Park Service, was chosen to oversee construction and installation of the exhibits. Phillips, along with a committee of museum and media experts, visited potential contractors who were interested in the project, selecting the most qualified and negotiating a favorable contract with each. The Museum of Westward Expansion crowned Phillips' National Park Service museum building career, and he retired as planned on July 30, 1976, two years after starting the job and just days before completion.

The Museum of Westward Expansion was completed on August 10, 1976, with a dedication ceremony on August 23. The total cost of the museum was $3,178,000, [10] and when completed it was the largest museum in the NPS. [11] In a space nearly the size of a football field, twenty major themes relating to 19th-century American history were presented. Two hundred historic artifacts were used to illustrate the material culture of American Indians, soldiers, explorers, mountain men, miners, farmers, overlanders, and cowboys. None of the objects were labeled or explained with words. Artifacts were to be understood by association with hundreds of historic photographs and quotations from the people who made history. The museum featured huge black-and-white and color photomurals, giving visitors an immediate reference to the people, the environment, and the time period being discussed in a given area. [12]

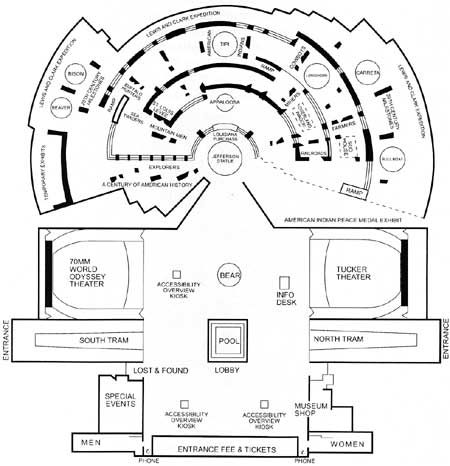

Visitors entering the Museum of Westward Expansion were literally funneled down a short, narrowing corridor to stand beside a life-size bronze statue of Thomas Jefferson, which was at the center point, "ground zero," of the museum. From Jefferson, concentric half circles, each representing a decade of the 19th-century, fell away toward the distant photomurals on the back walls. Wedges within this huge half-circle carried the 20 major themes of the museum outward from Jefferson like the spokes of a wheel.

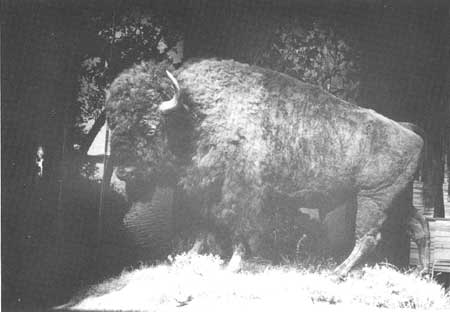

Visitors were given many options for viewing the exhibits through this museum design. They could choose a theme of personal interest and follow a wedge from Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase in 1803 to the dawn of the 20th-century. They might also choose a decade such as the 1840s, and follow the half circle around the museum to consider the interactions of various peoples during that time. Visitors might be attracted to the color photomurals, 15 feet high and 600 feet in total length, finding themselves suddenly immersed in the Lewis and Clark expedition, month by month, camp by camp. Still another visitor option was to start out along the history wall, a potpourri of 19th century facts arranged in the fashion of a huge time-line. Visitors enjoyed mounted animal specimens scattered throughout the museum, suddenly coming face to face with a huge bison bull, a longhorn steer, or beavers busily building a dam. The well-mounted skins of these and other animals gave the illusion of life, and portrayed some of the non-human contributors to Western history. A 21 screen audio-visual wall, 110 feet long with rear-projection screens 20 feet high, was built along the north side of the MWE. Approximately 750 slides were shown in a 13-minute program which gave an overview of Western history. [13]

|

| Map of the Museum of Westward Expansion. |

|

| Mounted bison specimen, Museum of Westward Expansion, 1976. NPS photo. |

Interpreting the Museum

The major management problem with this unique museum design was at the point where its strength became a weakness, as described in the original 1976 museum literature: "Visitors are not isolated from the exhibits by glass, walls or barriers. In this way it is hoped that they will become a part of their heritage. Risks are involved in this concept; too much touching can destroy objects. Park rangers are on duty in the museum to help remind visitors of this fact. Rangers also act as interpreters, providing information about individual objects as well as concepts and overviews of Western history." [14] This major duty was assumed by the interpretive division from 1976 onward. An average shift in the MWE for an interpretive ranger involved an unusual mix of dispensing historical information and protecting the resource through verbal reminders. "Roving the museum defines a fine line between interpretation and resource protection," said Chief of Museum Services and Interpretation Mark Engler. [15]

I believe our staff has struggled with this issue in the sense of wondering if we are interpreters or guards. This function is essential to the protection of the museum. I believe that good interpretation can incorporate a balance between the two. We have tried to stress the creative approaches to accomplishing this goal. We use things like puppets, and try to get the kids to "police their parents" in the respect of not touching items in the museum.

I am very comfortable with the wide-open concept of the museum, and would hate to see anything happen to it. The museum leaves room for us to expand upon sub-themes, as we have done with the Indian Peace Medal Exhibit. We will, I believe, be able to branch out in other directions. As we perform rehabs on the museum, we will constantly look for opportunities to tell more of the story. We will enhance our exhibits by preserving the artifacts in them, and expand on the themes to eventually include all the cultural groups involved in the settlement of the West. [16]

Visitor Center Rehabilitation

With visitor use patterns established in the Gateway Arch Visitor Center by the late 1980s, and new features such as the 70mm theater and American Indian Peace Medal Exhibit in progress, the superintendent and chief of interpretation began to discuss a more cohesive and unified design for this area. Mark Engler explained:

One of the major concerns of the people working at the Arch was the immediate disorientation of visitors as they enter the complex, and ways that we might be able to improve that situation. They felt it was important that the visitor feel a sense of security and orientation upon entering the building, and that the design should address visitor flow. We brought in Dan Quan Associates of San Francisco to look at the facility and create an interpretive lobby plan. The plan will look at general design issues, and lend an air of consistency to the entire visitor center. Some of the other projects discussed included the installation of a closed-circuit television camera at the top of the Arch, with a direct link to other gateway parks such as the Statue of Liberty and Golden Gate. A sign plan for the grounds will also be looked at, as well as new treatments for the theater entrances, executed in brick. The tram load zones will also receive new treatments, exhibits that tie humans and their environment directly together. This is another way of looking at management objectives, but on a much broader scale. We can represent them graphically in the design and layout of the Visitor Center. [17]

By 1991, this project was underway, with a master plan being written by Dan Quan. [18]

Old Courthouse Exhibit Galleries

Exhibits in the Old Courthouse which were created in the 1940s were revamped and expanded in the 1970s. A "living history fur trade room," "loom room," "pioneer cabin room," and an environmental education workshop-library were opened in August 1972. A reproduction of a 19th-century doctor/dentist's office was opened in the east wing of the first floor by the St. Louis Medical Society on February 5, 1975, and on June 8, 1976, the dedication and opening of a "St. Louis Room exhibit" took place, created with funds donated by the First National Bank of St. Louis. [19]

Despite these varied efforts at interpreting life in early St. Louis through exhibits, a unified group of displays with a common theme and design was needed for the Old Courthouse. The development of an Old Courthouse exhibit project began in the late 1970s, and JEFF and Regional Office staff members examined 12 different proposals by the end of 1978. Three of the firms who submitted proposals were chosen to develop preliminary plans. Of these, Aram Mardirosian's Potomac Group developed a design which best reflected the use of the Old Courthouse by making the building itself the main exhibit. In 1979 Mardirosian revised the plan after a staff review. [20] The 1970s era displays were removed by August 1980, leaving the Old Courthouse with virtually no exhibits for nearly six years. [21] As a stop-gap measure, Park Technician Nancy Hoppe designed a temporary display of historic photos of the Old Courthouse, which was installed in a room on the first floor. This display remained in place until the completion of the Mardirosian exhibits. [22]

|

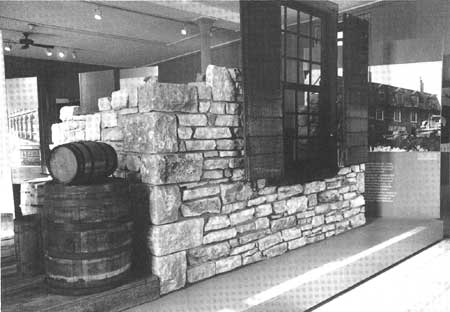

| Map of the Old Courthouse Exhibit Galleries. |

The Old Courthouse exhibit project was completed in May 1986, when four new St. Louis history galleries opened. [23] In the old courtrooms of the south wing, displays with the themes "St. Louis: The Early Years (1764-1850)" and "St. Louis: Becoming a City (1850-1900)" were installed. The north wing galleries presented "St. Louis: Entering the 20th Century (1900-1930)" and "St. Louis Revisited (1930-Present)." Photo exhibits in the rotunda featured the history of the Old Courthouse and close-up views of the murals in the dome. Exhibits concerning the Dred Scott decision were installed in the west wing on the first floor, where the original courtroom in which the case was heard had been located. A room was dedicated to the display of the top five drawings from the 1947 architectural competition, from which the design for the Gateway Arch was selected. The new exhibits for the Old Courthouse were considered to be modern and fresh in concept. They featured reproduction artifacts and an open design similar to that of the MWE, which allowed the exhibits to be viewed free from the burden and obstruction of exhibit cases and glass barriers. The "Prologue" or "Mississippian Gallery," which described the lifestyle of the St. Louis area's pre-Columbian civilizations, was opened in September 1987, completing the new permanent exhibit plan. Air conditioning systems were installed by May 1988, to create a suitable environment for the new exhibits and a comfortable working situation for employees and volunteers, who due to the new open exhibit design had to be stationed in the galleries. Primary funding for the exhibits came from the park's development fund from Bi-State Development Agency. As a whole, the galleries presented a panoramic overview of the city's history, and helped make the Old Courthouse a cultural attraction. [24]

|

| One of the new exhibits in the Old Courthouse, "St. Louis Revisited," featured portions of the historic Old Rock House, built in 1818. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

To complement the new exhibits, the information/orientation room on the East side of the building underwent major changes in 1985, with the addition of a large wooden information desk and an oval display rack to accommodate the growing number of sales items. A 1/4" transparent scale model of the Old Courthouse was installed, allowing interpreters and volunteers, through the use of fiber optics, to explain the changes in the building and its expansion over the years. [25] Gradually, the orientation room was usurped by sales space as the museum shop inventory grew. Eventually, orientation programs and visitor reception shifted to the rotunda. [26]

The Museum Education Program

Beginnings: 1977-1980

For many years, interpretation at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial was accomplished through non-personal services. With the exception of talks given at the Old Courthouse, exhibits were the primary interpretive medium employed. With the opening of the Museum of Westward Expansion in 1976, however, personal interpretation began to play a much larger role.

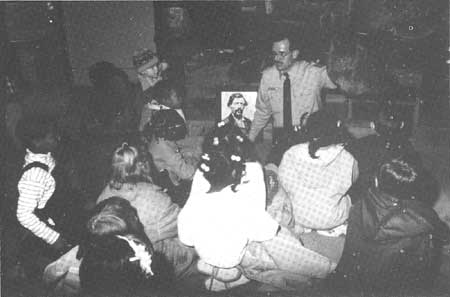

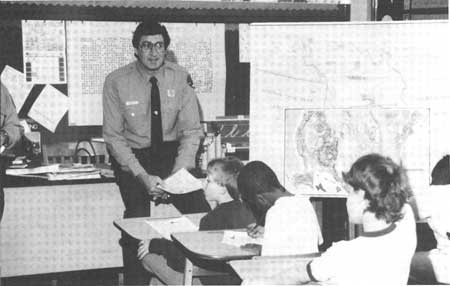

In 1977, attempts to expand the Memorial's interpretive efforts beyond the site and into the community resulted in the creation of a museum education program within the Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association and the hiring of Ray Breun as a museum education specialist. [27] The program was designed to create a learning atmosphere for both school children and adult groups who came to the MWE and Old Courthouse. Services ranged from general museum tours to specialized presentations on St. Louis history and architecture. [28] Ray Breun recalled:

When I [was hired] I had nothing to do with the sales division at all. . . . In June of 1977, Norm [Messinger] walked into my office and said I would have to start a museum education program, and he would oversee it and sign off on whatever was decided. . . After the museum opened, the word got out to schools real fast, and the very first year after it opened, they had 36,000 school kids. It was just amazing, and they were quite surprised at how many people came. . . By the spring of 1977, the Park Service interpretive staff said "We cannot handle any more kids." But they knew full well that they were going to get more than 36,000 the coming year. So in June of 1977, . . . I went to the various universities and picked up [three] intern volunteers in Masters Degree programs. . . We worked out the type of basic program to have in this museum, and how to relate it to the Old Courthouse. . .

So we came up with an opening tour, and Norm wanted to know how many school kids I thought we would have. Now, I said based on what the other museums do, and the fact that we are open on Mondays, when all the other museums are closed, I would expect the visitation to at least triple, if not quadruple in one year. And it did. We ended up handling as many people in April and May of 1978 as we had the entire previous school year, '76-'77. . .

We worked out a basic structure that we wanted all interpreters to have [regarding] interpretation in general, and school folks and various audiences in particular. Out of that came what we called the pre-test. We had a test for the entire interpretive staff, those that were here and any new ones who came on duty. They could "test out" of training [if an employee passed the test they did not have to attend the training session]. . . We gave the test to the existing interpretive staff, and it took each person a little over three hours to complete . . . In August we did the pre-test, in between time we had been writing our heads off, trying to get all those packages done, get the interpretive materials finished. In September we did the training for the staff, and we had two 80-hour classes; by the end of September, we were giving tours.

[In 1978] we handled about [92,000] school kids, so we went from 36,000 to about [92,000]. We also began the process of writing information sheets on various objects in the collection. We put together the first 19 slide packages and put those out by mail [to the schools who requested them as pre-visit kits] . . . [29]

By 1978 JEFF interpretive programs included classes, workshops for teachers, a publications program, and accredited intern and research programs with area colleges. During that year, more than 2000 groups utilized the Museum of Westward Expansion's resources. [30] However, the program lacked a synthesis with the curricula in the local school systems. Each interpreter developed his or her own themes and outlines based more on the title given to the individual program than on specific educational objectives. [31]

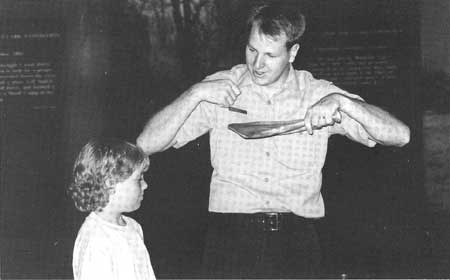

Folklife Program

After the opening of the Museum of Westward Expansion in 1976, Assistant Superintendent Norman Messinger realized the potential for arts programs in the new museum setting. Using leftover Bicentennial funds, Messinger sought the expertise of the Missouri Friends of the Folk Arts in the development of a museum concert series. Fifteen concerts of traditional music were held over a period of seven months, and were very successful. In February 1977, a temporary position was funded by JNEHA to coordinate folk arts activities, including music and crafts demonstrations, in the museum. Later in 1977 the position became permanent, with the program coordinator raising funds from corporations and arts endowments, organizing public programs, festivals and conferences, and serving as a resource person for the community and NPS staff. Through public programs, seminars, community contacts and exhibits, the Folklife Program sought to instill in visitors an appreciation and understanding of traditional arts. [32] Demonstrations of crafts and music such as saddle making, cowboy songs, quilting, storytelling, American Indian button and ribbon work, old-time fiddling, and basketmaking made aspects of the past come to life for visitors. [33]

Education Program, 1981-1985

In 1981 a brochure describing the museum education program's various services was prepared and sent out to area schools. For pre-school and kindergarten there were storytelling and sketching at the Old Courthouse, and exploring tours in the Museum of Westward Expansion. First grade programs focused on family roles and relationships. Grades 2 and 3 explored natural and man-made communities in the West. At the 4th and 5th grade level, students were introduced to such topics as transportation and geography in the Museum of Westward Expansion, and the role of the Old Courthouse as a legal institution. Programs for grades 6-8 included the role of various ethnic groups in the West, an in-depth look at the Old Courthouse and its role in St. Louis' social history, and an introduction to the National Park System. For high schoolers, topics included women in the West; Thomas Jefferson and westward expansion; the effect of expansion on American Indians; an architectural tour of the Old Courthouse; a tour of the Old Courthouse and Luther Ely Smith Square to discuss parks and the urban environment; and walking tours of the downtown area. [34]

In 1981 the program was broadened further to involve the St. Louis Public Schools' Partnership Program. This special school program was previously directed toward introducing students to business sites. Jefferson National Expansion Memorial created the pilot program for the participation of cultural sites in Partnership Programs. The success of this program led to its expansion to all the cultural museums in the St. Louis area. The Partnership Program was managed by three employees, hired by JNEHA, who also carried the park's Folklife Program into the schools. [35]

With financial assistance from the Missouri Committee for the Humanities, the JEFF Museum Education Office prepared a number of learning packages, consisting of slides and accompanying handbooks. Topics included architecture, St. Louis and Missouri history, women of the West, and U.S. Presidents who affected westward expansion. Yet another aspect of the program was the Traveling Exhibit Program, funded by the Missouri Arts Council, in which reproductions of paintings and photographs on a number of topics were offered for display in museums, galleries, schools, libraries, and other public facilities throughout the state. [36]

In the early 1980s, however, the Museum Education Office was, according to the park's annual report, "largely an outreach program for schools, small museums, scouts and nursing homes who can use our resources but cannot often come to the Memorial. . . . Maintaining this program is a bare minimum of what can be done in outreach." Most of the focus was on the Frontier Folklife Program and the craftspeople who were brought into the park to provide concerts and demonstrations. [37]

Education Program Revisions

JEFF school programs were revised in 1985 due to two factors. The first was the boost in support received through NPS Director William Mott's 12-point plan on the role of urban parks in education. The second was the passage by the Missouri State Legislature of the "Excellence in Education Act," which encouraged schools to justify field trips based on Missouri Core Competencies and Key Skills. During the summer of 1985, a Museum Education Program (MEP) committee, which included front-line interpreters from the Gateway Arch and Old Courthouse, began considering ways to strengthen the education program at JEFF. The committee produced several suggestions. Program requests were tracked to better understand the needs of area teachers, and how the park might integrate themes and objectives into local curricula. Work was started on producing a booklet or guide for MEPs to expand and revise the shorter MEP brochure. [38]

Another change which affected the Museum Education Program was the demise of the Folklife Program. [39] Craftspeople from the program were responsible for presenting Partnership Programs in the schools, demonstrating frontier skills with music and handicrafts. When funding for the Folklife Program ended, a 180-day seasonal employee was hired by JNEHA to continue the off-site portion of the Partnership Program. "The interesting thing," remarked Breun, "is how [the Partnership] funding comes from the Arts and Education Council, which solicits the money from various corporations and individuals. They give it to the school board, and then the school board pays us." [40]

In 1985, 60 classes took part in the four-session Partnership Programs. Pre- and post-site sessions conducted at the schools, as well as programs at both the Old Courthouse and the Museum of Westward Expansion, gave 1,800 students an in-depth look at the park and its resources. Both students and teachers concurred that the benefits of the four sessions were far greater than a program based on a one-time visit. Many front-line interpreters, however, felt that the program lacked coordination and cohesion; whether folklife people or the Partnership Program's seasonal employee went out to the schools, their programs were essentially different and often at odds with what the interpretive staff presented when the same classes visited the museum. [41]

|

| Park Rangers Cathy Pellarin (near the pillar on the left) and Eleanor Hall (in the dress and apron, foreground) conduct an overlander program for a group of 4th graders in the Museum of Westward Expansion. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Consequently, Park Ranger Rick Ziino drafted a proposal to use the contract money from the St. Louis City Schools to fund a year-round program rather than a 180-day seasonal employee, and pay the salary of a full-time education program specialist at JEFF. On June 1, 1986, a non-NPS education program specialist position was created, funded by the St. Louis City School System, with additional funds from JNEHA. During the summer the new education specialist, Sue Siller, was able to coordinate a complete revision of the Partnership Program in which St. Louis school classes took part, with the incorporation of new themes and coordination between the on- and off-site portions of the program. As a result, the program increased in size by 25% in 1986 over the previous year. [42]

|

| JNEHA Ranger Tim Butler conducts an educational program on the fur trade in the Old Courthouse, May 1990. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Education programs, previously conducted only during the traditional nine-month school year, were expanded to a year-round format under the direction of Siller. This began with the Summer Education Experiences (SEE) program, a summer school session for inner-city students in need of remedial attention. JEFF's education programs, with their "hands-on" approach, proved to be very effective in this context, and led to participation by other schools, day camps, and scout groups during the summer months. [43]

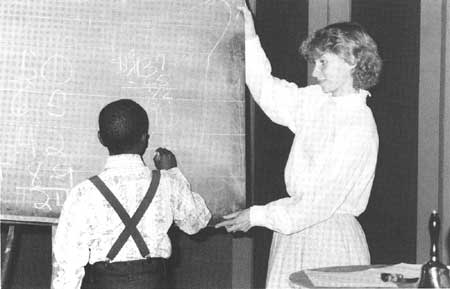

The education and interpretive staff developed programs which were broader in scope, curriculum-based, keyed to the necessary competencies and skills, and more easily adapted for use with all age groups. For pre-school through 12th grade general tours of the Museum of Westward Expansion and programs about Native Americans and the lifestyles of the pioneers were developed. In addition, programs about Lewis and Clark and the fur trappers were created for 4th through 12th grades. At the Old Courthouse, programs on transportation and St. Louis lifestyles were available for all grade levels. For 4th to 12th graders, there were also Old Courthouse tours, a "fur trading post," and mock trials in the historic courtrooms. Two special programs were designed to emphasize the historical contributions of African-Americans and European immigrants to life in the United States. Costumes and a recreated naturalization ceremony helped to acquaint students with the immigration and naturalization process in St. Louis. [44]

JEFF also began working with local "magnet" schools on in-depth programs similar to the Partnership Programs. Magnet schools had narrowly focused curricula centered around such subjects as mathematics, performing arts, or ROTC. Even when such special resource schools emphasized non-social studies subjects, however, they were still required to cover a social studies core curriculum for their generally more talented students. [45] In 1986, a program was developed by JEFF with the Stix Investigative Learning Center, a magnet school for gifted students. Sessions were highly interactive and project-oriented. The majority of the programs were originally targeted for the 4th to 6th grade level, but in 1990 a high school and a pre-school program were introduced.

The high school program was performed in conjunction with the "World of Difference," a nationally recognized campaign aimed at reducing prejudice and discrimination. Park Ranger Eleanor Hall worked with the Theodore Roosevelt High School, a large inner-city school in St. Louis with a racially mixed student body. In keeping with the westward expansion theme, her program centered around minority groups in the West, including black and Hispanic cowboys, Chinese gold miners, and black homesteaders, and focused on how they overcame obstacles. [46] In the course of the program, Hall made visits to the school and the students visited the museum twice. Written assignments were required of each student about one of the racial or ethnic groups studied. They responded with poems, songs (including rap music), diary entries, and letters. A spin-off program involved a two-part presentation by another ranger, Jim Jackson, on early surveying techniques for math classes. The success of the presentation resulted in a High School Intern Program, in which three GS-1 seasonals were hired at JEFF and received on-going training throughout the summer and on weekends during the school year. [47]

A national initiative emphasizing early childhood education provided the impetus for the Partnership Program for preschool and kindergarten groups. Two programs were developed, one during the fall semester centering on holidays and one during the spring semester focusing on lifestyles in St. Louis during the 19th century. Students were very responsive, producing ornaments to decorate a tumbleweed Christmas tree and paper bonnets and stovepipe hats as a role-playing activity to recreate life in St. Louis at the turn of the century. [48] The popularity and success of such special school programs continued to grow into the 1990s.

|

| Park Ranger David Uhler conducts the off-site portion of a partnership program, 1991. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

New Directions

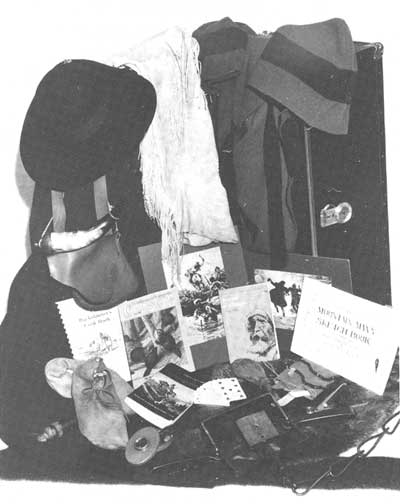

As the museum education program evolved in the 1980s, changes were made. Traveling exhibits were dropped, the slide packets were retained, and a new feature, "the traveling trunk program," was developed by JEFF Historian Jon James and Education Specialist Sue Siller in 1987. Originally called "Traveling Suitcases," the program began with containers of various sizes which could be mailed to those area classrooms which, due to fiscal or time constraints, could not make site visits. The suitcases, which were later expanded to footlocker-style trunks, contained "hands-on" objects such as reproduction objects and clothing, mounted photographs, and teacher handbooks in the form of scripts which linked the objects together and told a story. The trunks became extremely popular among schools, scout camps, nursing homes, and libraries. Videotapes were later added to the list of resources available in each trunk. [49]

|

| The contents of a traveling trunk on the mountainmen reveal the educational potential of this unique program. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

During the 1980s, the museum education program became less dependent on outside funding and staffing. In September 1987, a reorganization, prompted by the program's success and expansion, resulted in the addition of five "education interpreters" who worked under the direction of Education Specialist Sue Siller. The education staff was funded entirely by JNEHA [50] and presented educational programs in the MWE, as well as researching and producing many educational resources such as traveling trunks, slide packets, video programs, and computer activities for the classroom. [51]

By 1988, the demand for school programs, partnership programs, traveling trunks and other educational services reached a level at which a receptionist was needed, along with a computerized reservation system. This increased the efficiency of making reservations for museum education programs, as well as pre-visit educational materials. A new position was also established for a museum education assistant. [52]

Greater teacher involvement and improved quality of programs and services marked the direction of the museum education program in the 1990s. By 1991, 100,000 children participated annually in JEFF's museum education programs. The completion of a traveling trunk about wolves and the enhancement of several existing trunks expanded the scope of the program. Pre-visit material for the Old Courthouse education program and the Dred Scott program was developed, and the education staff implemented a selection of special programs for scouts based on their handbooks and badge requirements. The programs proved quite popular, with 1,400 scouts participating in the first three months alone. [53] An interpreter from Saguaro National Monument (Arizona), was invited to work with JEFF staff on conducting teacher workshops in 1991. In addition, JEFF was accepted into the Educator Career Internship Program for the summer of 1991. This program, sponsored by the St. Louis Schools, provided a teacher to work on-site for five weeks to produce teacher guides, provide staff training, and to evaluate the entire education program. [54]

The Pacific Northwest Regional Office, in cooperation with The Oregon National Historic Trail, requested that JEFF produce a K-12 curriculum celebrating the Oregon Trail Sesquicentennial. The Oregon Trail: Yesterday and Today, a product of exceptional quality, was produced; a second curriculum on the Columbus Quincentennial was in production at the end of 1991. [55]

|

| The highlight of many educational visits to the Old Courthouse in the 1980s was the opportunity to act out the Dred Scott Trial in one of the building's historic courtrooms. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

|

| Schoolchildren took on the roles of the judge, lawyers, Dred Scott and the jury. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Interpretive Programs in the Late 1980s

Interpretive talks in the Museum of Westward Expansion were offered nearly every half hour of the day by 1986. These programs enabled all visitors to attend a personal interpretive service if they chose. As a result, a 69% increase in program attendance over the previous year was noted. A full-sized reproduction tipi was added to the permanent museum exhibits in 1986, and a puppet stage added variety to both public and education programs. [56]

Several changes in visitor services took place during the summer of 1988. In May JEFF began an entrance fee program based on the honor system and the use of special fee collection machines. In support of the program, interpretive park rangers furnished information and assistance in operating the machines, as well as help for visitors in planning their activities. The crush of the crowds was so hectic, however, that this added interpretive function lasted only through the summer of 1988. Simultaneously, a program was instituted consisting of a 5-to-7 minute introductory talk in Tucker Theater before the start of the film Monument to the Dream. It was quickly discovered that these talks were far more effective in informing visitors about park programs than trying to make contact in the lobby at the fee collection machines. The theater talks were continued after Bi-Sate assumed control of collecting the entrance fee. [57]

The duties of JNEHA employees were expanded to include public programs and all duty stations in the Gateway Arch. As a result, their productivity increased, and the complexity of daily scheduling was eased by fully integrating JNEHA interpreters into daily operations. [58]

In 1989, a plan was developed to convert the interpretive offices in the Museum of Westward Expansion into a more efficient workspace for up to 25 employees. Charles "Corky" Mayo, Chief of the Division of Museum Services and Interpretation at the time, recalled that when he arrived in the park, "the interpreters sat on the concrete floors back there with books on their laps." [59] Computer equipment was purchased and modular office space designed to serve the needs of the interpreters. [60] The new interpretive workspace was an important change, boosting employee morale and providing desktop areas, book and note storage, and a "personal space" for each interpreter. [61]

"When I got to the park," recalled Mayo, "morale was low. I thought, what can I do to help this situation? First, I had to empower people to have a say in what they do. I sought input from the staff on decisions such as the construction of the information desk. I told people, don't worry about what we can do, we can do whatever we want. We have to choose the right idea!" [62]

In May 1990, Corky Mayo transferred to the Pacific Northwest Regional Office, and Mark Engler of Saguaro National Monument was selected to replace him. [63] "On my arrival, I looked first at the personal side," said Engler.

I wanted to inspire a new level of self-confidence in the interpretive staff, giving them opportunities to participate in programs and activities to enhance the division's operation, but also to help build a solid base for their individual careers. I wanted to emphasize communication, developing an efficient team; I wanted to look at individual programs and their structure. [64]

New programs for park visitors included expanded services for the disabled. Substantial work in improving the park's library, the removal of architectural fragments from the 1939-42 demolition of riverfront buildings to an off-site location, and improvements in the existing temporary exhibits program characterized Engler's tenure. A shift was made in the discussion of the major interpretive themes, moving away from an emphasis on "manifest destiny" and the "conquest" of the West by predominantly Anglo-Saxon Euro-Americans, toward a more subtle and all-embracing multi-cultural interpretation of the story. Mark Engler explained:

We try to be objective in our story lines — telling the story accurately, but portraying all groups of people, not just Euro-Americans. This memorial was, from the beginning, created to commemorate the ordinary people who settled the West. No one said that meant only the descendants of the Jamestown and Mayflower settlers. Ordinary people who settled the west included African-American, Chinese and Japanese immigrants. Spanish settlers lived in the Southwestern United States before the colony of Jamestown was even founded. The West was settled by men and women from nearly every part of the globe. This memorial was also meant to include, I believe, the first settlers of the West, the American Indians. So we incorporate all of these groups into our interpretive programs, and it isn't a stretch at all. I think we present the story of the West in a more positive and accurate light now than if we were still talking about manifest destiny and accentuating only one group of people.

I think that we are lucky to have such a wide range of themes. Because of this, interpreters here have an opportunity to grow, to share different segments of the history of the West, St. Louis, and the Old Courthouse. . . . We try to include management objectives along with these themes in our presentations. I believe that our programs should do more than entertain. In this way, we can actively demonstrate the power of the role of interpretation. It would be hard to cut a program that would save $100,000 a year by simply discussing the conservation of objects in the museum or litter control on the grounds. So through the use of management objectives we can make an immediate and positive contribution to the public's appreciation for the park and for the goals of the NPS as a whole. [65]

|

| Assistant Education Specialist Diane James conducts a Frontier Classroom program. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

JNEHA and Interpretation

In the Operations Evaluation of May 1982, it was noted that:

The budget of the interpretive division increased $92,000 from 1979 to 1982 to a total of $547,600. Despite the increase, and the fact that the cooperating association funds almost all supplies and materials and personal service costs for five employees of the division, there has been a steady decrease in available personal services. . . . Interpretive programs as a whole are going downhill. There is now a $150,000 deficit between the purchasing power in 1980 FY and the 1982 FY allocations. Programs have been reduced or eliminated in order to compensate. Judgment at the park is that something else has to close in 1983 in order to balance operations with allocations. Alternatives seriously considered have been to close the programs at the Courthouse, reduce the hours of operation, [or] reduce maintenance programs especially on turf and grounds. [66]

JNEHA Executive Director Ray Breun remembered that there "were a variety of things that happened in the last days of the Carter and the early days of the Reagan administrations, all of which basically meant that the Park Service staff was being reduced. . ." [67] Since the Gateway Arch and its Museum of Westward Expansion had become the premiere attractions of the park, when the money crunch came in the 1980s the first alternative considered for the reduction in the program was the closure of the Old Courthouse. Superintendent Jerry Schober recalled:

I mentioned to [the Midwest Regional Office] that if my budget kept coming out at what it was, I could not operate the Old Courthouse, and the Old Courthouse had become an intricate part of the operation. Apparently they weren't receiving those memos. I got my [FY '83] budget . . . and it wasn't enough to run [the Old Courthouse]. I mentioned [this] in the squad meeting, which I know Ray [Breun] was always sitting in [on]. And I said, "Well, we're going to have to close the Old Courthouse." And that appeared in the newspaper. [68]

I presume Ray [mentioned it to the press], which I did not tell him not to do, but the idea was, I didn't ask for it to be put in there. I know it's not kosher for a manager to do it, but everybody figured I probably did it. But my heavens, you know the press, the Post-Dispatch was in here, "Well, what are you going to do?"

"The only thing I know to do, I have already sent out a letter requesting additional FTE and funds so that I can operate this [park]." And . . . the thing came back like lightning before it got up to the Region. Weekly I'd be called up by the Post-Dispatch saying, "Well, have they responded?"

I went to the Superintendent's conference; and the director of the Park Service [Russell Dickenson] was there. By then this thing had hit the Washington Post, that the Old Courthouse in St. Louis was going to close down because we didn't have enough money. And he [the Director] said, "Hey, good shooting, Jerry, really putting the pressure on us, aren't you?" But he smiled.

And so, I got back and I got a letter, or a memo [from the Regional Office], and it said "This is in response to your memo to us. Number one, you're not going to get any additional FTE; number two, you're not going to get any additional money; number three, you're not going to close down any visitor use areas. And I thought, well, I could understand that memo real well. And the press wanted to know what did it say; and I told them. And they said "What are you going to do?" And I said "Well, you know, I was like you, I was thinking about that same thing, but then I thought, well maybe that's why they call me a manager. I'm going to have to come up with something so that I can do what my superiors told me to do." And they said "Alright."

So I got Ray Breun over, and he sat down, and I said "Ray, I want to keep this courthouse going; this is where a lot of history took place . . . with the Dred Scott [decision]. This is something earth-shaking. So I said, how about this: let's do an addendum to your [cooperative] agreement, and you run the theater down there [at the Gateway Arch], (it had always been free), and let's charge 50 cents a ticket. [Ray] felt that he could pay people who were going to do the same thing [rangers do] in gray and green only they're going to have a different color uniform. And we've already agreed that it's not "us" and "them." They'll come in, they are making the same money, we want to give them the same training, we want them to have the same commitment. There's one thing we shared: and that was a mission.

I had already done an agreement once before with the association at Gettysburg, where they did certain services for me. They did all the [custodial work], and they paid for it. In fact, I didn't realize it at the time, but that was the only written agreement an association had ever had. I didn't know it was going to come back to haunt me. Before long they decided hey, everybody ought to have one of those. So we ended up having one here [in 1982] . . . [69]

In 1985, with JNEHA-funded rangers in place at the Old Courthouse, budget cuts again began to affect the park with possible cutbacks in hours, this time at the Gateway Arch. Superintendent Schober amplified:

[In 1985] we were short money again, and we were short people. Now I had to go to the Region [again]. Regional Director Chuck Odegaard was there, and I had to sell him on the idea that I could dedicate four people during the day down under the Arch to provide information and make sure the artifacts were not harmed or removed or anything like that. "Why couldn't this be a job the Association could do?" He said "Well . . . humph . . . " He couldn't argue with that because it wasn't taking more money from them. [70]

Superintendent Schober ordered this major change in staffing for the Museum of Westward Expansion in the fall of 1985. The responsibility for roving, interpretation/ protection duties in the museum switched from NPS interpreters to interpreters funded by JNEHA. National Park Rangers were assigned to duties at the entrance to the MWE, the information desk, the top of the Gateway Arch, and an occasional program. The JNEHA staff became the "guards" roving the museum. Park Service employees could not present school programs, JNEHA employees could not put on public programs. This division of duties caused dissention on the part of the staff, with each group wanting to perform duties delegated to the other, and an expressed wish to serve on a co-equal basis. [71]

|

| JNEHA Ranger Kurt Hosna speaks with visitors in the Museum of Westward Expansion, May 1988. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Superintendent Schober continued:

To make this a short story, [JNEHA employees] began to say "Hey Jerry, we stand down here, we listen to the story, we study it to be able to give information; we're doing the same thing the [NPS] interpreters do." And, you know, I'd love to tell them no, but they were. And by now, we've convinced Civil Service that when an opening comes, these people have been performing that job, why can't they be entitled to apply for it? Now . . . I have to go back to the Region this time and say, "They've done a great job down there, can you see a reason why they couldn't be interpreters?" And it would mean their grade, also, went up a little. . . . And you know, you've got to give it to the Region, they were supportive. Sometimes, I'm sure they held their breath. But they were supportive. [72]

In 1988, the Regional Office granted permission for JNEHA and NPS rangers to perform the same interpretive functions in the Museum of Westward Expansion, under NPS supervision. The unique situation of funds provided by JNEHA for programs and personnel eased the strain on the JEFF budget caused by Federal budget cuts and cost-of-living salary increases during the 1980s. [73] Mark Engler summarized the park's point of view regarding the JNEHA rangers and their place in the operation:

They are essential. Without the rangers, librarian, archivist, exhibit staff, and projectionists we would be dead in the water. We look at these people as being the equals of the NPS staff and hold them to the same standards and expectations that we do the people wearing gray and green. The only difference is in where the money comes from to pay them, and the color of their uniforms. The ideal would be that the staff would be entirely paid by the NPS, that they would all be NPS rangers. This, unfortunately, is not possible because of the budget, nor is it likely to be possible in the future. But it shows how strongly we feel about the staff, and that the JNEHA people are not "auxiliaries," but considered to be full-fledged rangers. [74]

Special Interpretive Activities

Frontier Folklife Festival

In addition to the regular interpretive and museum education activities at JEFF, there have been a number of special interpretive programs developed over the years. Some, like the Frontier Folklife Festival, began in the late 1970s and ended in the 1980s. The first folklife festival at JEFF took place over the Labor Day weekend of 1977, an expansion of one held the previous year at Washington University in St. Louis. The Mississippi Valley Folk Festival featured American folk culture through American Indian, ethnic, Afro-American, and Anglo-American traditions using music, dance, and crafts. The National Park Service cooperated in the venture with JNEHA, the Missouri Friends of the Folk Arts, the National Council for Traditional Arts, and the Missouri Arts Council. In 1978, the event became known as the Frontier Folklife Festival to tie it more strongly to the primary interpretive theme of the Memorial. The 1983 festival drew 60,000 people and featured 70 artists. [75]

|

|

| Basket weaver at the Frontier Folklife Festival. Photo by Norman Messinger. | Sheep shearing at the Frontier Folklife Festival. Photo by Norman Messinger. |

For seven years, the Folklife Festival was an annual summer event at the Memorial, but after 1983 funding for the program was needed elsewhere, specifically to pay the salaries of employees hired by JNEHA to staff the Old Courthouse. JNEHA sources were also depleted after sponsoring a major exhibit of Charles M. Russell paintings in 1982. [76] Then-superintendent Jerry Schober commented: "I'd had a folk festival in California [at Golden Gate], but I felt like folk festivals didn't have to be totally paid for by the Park Service. If there was that much of a following, then you ought to be able to go out and get support. . . Their outlay [all JNEHA funds] was about $70,000 a year, and they didn't bring anything in." [77] As a result of park-wide budget cuts, Schober discontinued funding, telling supporters of the program that it could continue if outside money could be found to pay for it. The cancellation of the festival caused a great deal of hard feelings on the part of supporters. Despite an effort on the part of the performers and folk enthusiasts to save the festival, alternative funding was never found for its continuance at the Arch. [78]

Storytelling

Another special cooperative interpretive event hosted by the Memorial was the annual Storytelling Festival. This program, jointly sponsored by JEFF and the University of Missouri-St. Louis, was started in 1980. The four day event was traditionally held on the first weekend in May, and featured 25-30 nationally and locally known storytellers each year, presenting public performances at the Museum of Westward Expansion and the Old Courthouse. Attendance at the festival ranged between 10,000-15,000 people throughout the 1980s, peaking at 20,000 in 1986. Beginning in 1987, JEFF Chief of Museum Services and Interpretation Corky Mayo insisted upon interpretive themes for each festival, the first being "Star Spangled Stories." [79] Although themes in accordance with the NPS, St. Louis history, or the history of the West were insisted upon, it was often difficult to make the storytellers understand the importance of fully tying their event to the programs at JEFF. "We have had an ongoing discussion with the Storytelling people about themes here at the Memorial," Mark Engler said. "Since our theme base is so large, we felt they could help us by telling stories which fit in with our themes. This has been a real battle at times, and we threatened to cancel the 1991 festival because of a lack of cooperation on this." [80]

|

| Storyteller Bobby Norfolk at the 1985 festival. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Black Heritage Month

The Memorial's observance of Black Heritage Month made its debut in February 1980. During the early 1980s, Black History Month featured movies and programs in music, dance and storytelling, more entertaining than interpretive in structure and delivery. [81] In 1984, however, an original dramatic reenactment of the Dred Scott trial presented by the interpretive staff and local residents became the culminating event of a schedule called by the Washington Office "one of the most ambitious in the NPS," and pointed the way for the future of the program. [82] In 1986, the Dred Scott trial ran for one full week, and was presented in the Tucker Theater and at the Old Courthouse. [83] By 1987, entertainment activities were replaced with interpretive programs on the African-American role in westward expansion, attracting 7,146 visitors. [84] These programs were offered to both the general public and school groups, and led, by the conclusion of the decade, to a year-round program of school and public presentations on the African-American experience. [85] In 1988, to accommodate the overwhelming popularity of the Dred Scott trial program, its location was moved from a courtroom to the rotunda. An exhibit was created on African-Americans in the fur trade, accompanied by a sound track containing music by black composers. [86]

|

| John Toomer portrayed York, the only African-American member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, for Black Heritage Month in 1990 and 1991. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Further change was noted in 1989, when in addition to presentations by park interpreters, outside groups were invited to participate in the January 15 through March 4 celebration. Company A of the 10th U.S. Cavalry, re-enactors from Fort Concho, Texas who portrayed the "Buffalo Soldiers" of the 1860s-90s West, were a highlight of the program. Storyteller Opalanga Pugh recreated such historical figures as Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. At the Old Courthouse, the "Freedom School" program was developed to teach school groups how free black children were forced to obtain their education in secret in ante-bellum St. Louis. The month culminated in a week of dramatic re-enactments of the Dred Scott trial at the Old Courthouse, and drew 9,000 visitors. [87]

The 1990 celebration was held January 14 through March 3, and was attended by 24,000 visitors. Programs included special presentations by Robert Tabscott, a St. Louis historian and writer; Opalanga Pugh; and John Toomer, who recreated the thoughts and experiences of York, the only black member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Company A of the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers were again featured, and the Dred Scott Trial was performed by a community acting group and area choirs. Ranger-led presentations included a special week of "Freedom School" programs at the Old Courthouse, and "Blacks of the West" programs at the Museum of Westward Expansion. [88]

A new addition for the 1991 Black Heritage Month, held February 3 through March 2, included a series of concerts and a lunchtime lecture series with such noted authors as Dr. Walter Ehrlich, author of They Have No Rights: Dred Scott's Struggle for Freedom and Dr. John Wright, author of No Crystal Stair and The St. Louis Black Heritage Trail. [89] The Black Heritage Month Program continued to grow in the early 1990s, but more importantly evolved into a program of year-round presentations on African-American heritage in St. Louis and the West.

Christmas Programs

During the 1970s small Christmas programs began at the Old Courthouse, and beginning in 1981 Christmas noontime concerts were offered. "A World of Christmas" began as part of the folklife program in the early 1980s, and included a display of 16 different international Christmas trees in the Old Courthouse, with performances by children in ethnic costumes. [90] At the Gateway Arch, holiday frontier folklore presentations were given, with choirs and evening tram rides to the top of the Arch. [91]

A Victorian-era Christmas celebration was launched at the Old Courthouse in 1988, with a more ambitious program of special concerts. By 1989 "Victorian Christmas at the Old Courthouse" grew to include special children's programs, noontime concerts and participation in evening candlelight tours involving three downtown historic homes. Extensive decorations, including a 25-foot tree in the rotunda, drew 13,600 people. Beginning in 1989, a display of international Christmas trees similar to that once held in the Old Courthouse, entitled "A World of Christmas" was held at the Arch Visitor Center, representing the trees and customs of 10 different countries. [92]

In 1990 the Christmas program was expanded to include the entire month of December and included a variety of special holiday programs for both school groups and the general public, as well as continuing the noontime concerts and an evening candlelight tour. Once again, the Old Courthouse was festively decorated with an artificial 25-foot tree in the rotunda and garlands, greenery, and bows on the lights, columns, and balconies. There were also period Christmas decorations and trees in three of the St. Louis history exhibit galleries to reflect different eras in the celebration of the holiday in St. Louis. Fourteen concerts were attended by nearly 2,000 people, and 67 "Christmas in St. Louis" programs attracted nearly 1,500 visitors. [93] The program continued to grow in scope and attendance in 1991. [94]

|

| A 25-foot tall Christmas tree adorns the rotunda of the Old Courthouse for the Victorian Christmas celebration, 1988. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Scout Programs

In 1987, "Scout Day" was added to the interpretive programming at JEFF. Organized for area Boy Scout troops, the event featured eight different programs and activities in the Museum of Westward Expansion, the Old Courthouse, and on the Memorial grounds. By participating, scouts earned special badges; 1,200 scouts and leaders attended. [95] In 1988, a similar "Girl Scout Day" was developed. Scout days continued until 1991, the Boy Scouts meeting in the autumn and the Girl Scouts in the spring.

|

| Park Rangers Jim Jackson and Andy Kling present a program on mountainmen to boy scouts on the grounds of the Gateway Arch. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

The practice of relating school curriculum requirements to scouting programs was instituted in 1991, and the concepts for Scout Days were revised. A series of multi-session scout programs were developed dealing with park themes and fulfilling Scout handbook badge requirements. A special Gateway Arch scouting patch was designed and awarded for successful completion of badge requirements in 1989. The success of these programs was overwhelming. In 1987, nearly 2,000 scouts participated in less than three months. Attendance at Scout Days tapered off with the advent of regularly offered scout programs, and Scout Days were discontinued in 1991. [96] In addition to the high quality and success of the year-round scout program, JEFF participated in the annual encampment at nearby Beaumont Scout Camp in 1991. Interpreters attended stations at the camp, allowing scouts to participate in a variety of activities related to westward expansion. Approximately 2,500 scouts enjoyed the two-day event. [97]

Union Station Urban Initiative Project

Another unique program, begun in 1987, was the park's Union Station Urban Initiative pilot project which was developed as a way to bring the National Park system to St. Louis residents and visitors at the new Union Station shopping mall. Nearly 30,000 public contacts per year were made at the Union Station store by 1991, a significant projection of the Park Service message outside JEFF. The project matured into a seven-day-per-week summer program, and continued on weekends throughout the winter months through 1991. [98] Mark Engler noted:

Union Station gives us the chance to inject themes outside of our immediate themes, such as Presidential Parks, biological diversity, and firefighting. It is a place to experiment, to learn new methods, and to communicate a variety of ideas and management objectives. Here is the perfect place to tell the public about the Park Service as an agency. We can tell people how their parks and recreation areas are being managed, and ways in which they can help preserve and improve their national heritage as embodied in the national parks. [99]

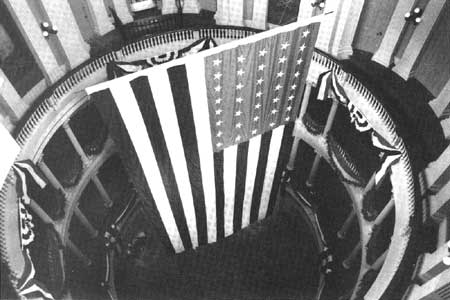

Victorian Fourth of July

In 1991, a new program was initiated at the Old Courthouse for the Fourth of July. Historically authentic decorations adorned the rotunda; handouts regarding historic Fourth of July celebrations in St. Louis were made available to the public; and a local band played popular patriotic music of the mid-19th century. Interpreters in period costume lent a special flair to the occasion, reading the Declaration of Independence and recreating a Frederick Douglass speech. The decorations were capped with a 36' by 20' United States flag of the pre-Civil War era, on loan from Fort Smith National Historic Site. [100]

Other Programs

Interpreters included interpretation of the U.S. Constitution in appropriate programs during the summer months of 1987. The traveling play "Four Little Pages" visited Tucker Theater for nine performances in the first part of July. A Mark Twain impersonator gave free programs during the locally proclaimed "Mark Twain Week" in December. [101]

|

| A 37-star American flag hangs in the rotunda of the Old Courthouse for the Victorian Fourth of July Celebration, 1991. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

A Fur Trade Symposium (sponsored by JNEHA) was held in November of 1989, which included outdoor living history activities and was attended by 20,000 people. [102]

Throughout the summer months, beginning in 1980, rangers periodically presented puppet shows based on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. With the acquisition of a new puppet stage in 1986, occasional performances were held in the Explorers Room in the Gateway Arch visitor center, and during an average summer day drew 2,000 visitors. They were an excellent way to bring the history of the park and the Park Service message to a young audience. [103] Regularly scheduled puppet shows began in 1990.

Women's History Week (March 11-17) was commemorated in 1990 with two special performances by a local theatrical troupe, the Holy Roman Repertory Company, entitled "Taking Heart: Women on the Frontier." Special exhibits and programs with an accent on women's history were employed during the early 1990s, organized by the park's federal women's program coordinator. [104]

Special Events

Ceremonies were held in May 1985 honoring former JEFF Superintendent and NPS Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., with the formal dedication and naming of the Gateway Arch visitor center in his honor. The dedication was attended by many of Mr. Hartzog's friends as well as his family. The morning of the dedication, Mr. Hartzog suffered what was believed to have been a heart attack and was unable to attend. William Penn Mott, who was sworn in as NPS director within a couple of days of the event, was present for the ceremony. [105]

25th Anniversary of the Gateway Arch

October 28, 1990 marked the 25th anniversary of the completion of the Gateway Arch. This milestone was celebrated with a variety of events and activities throughout the year. In February, Southwestern Bell distributed 2.5 million phone directories which featured a front cover dedicated to the Arch's silver anniversary. A student essay contest with the theme "Gateway Arch — Symbol of the American Pioneering Spirit" was sponsored by the Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association in honor of the 25th anniversary. A two-day symposium, "The River and the City: Riverfront Development in American Cities," was featured in October, and examined how the building of the Gateway Arch sparked the redevelopment of downtown St. Louis.

In addition, three special exhibits dedicated to the Arch's silver anniversary were presented. "Gateway Art" was conceived and built by the park's interpretive, exhibit, and maintenance staffs. It featured an eclectic assortment of items borrowed from local businesses and collectors which presented the Arch as symbol and icon for the people and city of St. Louis. The exhibit demonstrated the ways in which the Arch image became a pervasive part of the area's popular culture. The "Gateway Art" exhibit was moved from the special exhibit gallery at the Gateway Arch and re-assembled for display at the Old Courthouse through October 1991.

The local affiliates of the three major television networks, ABC, NBC, and CBS, featured 30-minute to one-hour specials about the Arch on the anniversary date. National programs such as Charles Kuralt's CBS Sunday Morning and the ABC Evening News with Peter Jennings featured Arch anniversary segments. Also, Good Morning America broadcast from the riverfront as part of its salute to the Arch's 25th anniversary.

|

| Logo used for the silver anniversary of the Gateway Arch, 1990 |

The 25th anniversary celebration culminated on October 28 with a public celebration which featured a "March to the Arch" ending on the riverfront. There, visitors enjoyed music provided by the Military Airlift Command Band from Scott Air Force base in Illinois, and a local band which featured music from 1965, the year the Arch was completed. National Park Service Director James Ridenour and local dignitaries spoke briefly about the significance of the occasion, silver anniversary commemorative medallions were distributed to visitors and participants, and the festivities ended with a brilliant fireworks display at dusk. [106]

The 75th Anniversary of the National Park Service

Great attention was given to the celebration of the 75th anniversary of the National Park Service at JEFF. Nine regions contributed more than 40 interpreters, and the National Capitol Region sent two U.S. Park Police officers to participate in this program, which coincided with the 1991 Veiled Prophet Fair. [107] Mark Engler recalled:

The NPS was looking for a place to showcase the National Park System for the anniversary. The VP Fair Foundation made an offer to NPS Deputy Director Herb Cables to host the anniversary showcase, which he accepted. The interpretive division was given the task of insuring that the NPS showcase was a success. We had every region except the North Atlantic Region participating, along with the U.S. Park Police, and Harpers Ferry Center. Almost every park in the country provided information, exhibits, or staff. Over 70,000 people participated in one of the NPS programs during the three day event. In addition, a new educational trunk on the NPS was developed, along with a new Partnership Program. [108]

Aided by large crowds who attended the fair, visitors enjoyed three days of interpretive vignettes representing the diversity found in parks as far away as Alaska and as close as the Ozarks. Four large tents housed exhibits, talks, travel information, brochures, costumed performances and demonstrations. [109]

The park staff conceived, designed, and built a special exhibit for the occasion entitled "The National Park Service: 75 Years in the Making." The exhibit featured a brief history of the National Park Service and emphasized its changing role and responsibilities since its inception in 1916. "The exhibit was opened on June 15 by Jim Fowler of TV's Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom, and received much media attention," continued Mark Engler. "This was a perfect opportunity to showcase the system and the people of the NPS." [110]

As additional parts of JEFF's observance, special interpretive programs were presented at St. Louis' Union Station on August 24 and 25. Rangers from parks across the country were invited to participate. Mark Engler recalled that "The actual anniversary of the NPS, August 25, was showcased at Union Station. Stew Fritts from the Grand Canyon was here, and several people from Ozarks National Scenic Riverway." [111]

The NPS 75th Anniversary Symposium was held at Vail, Colorado, in 1991. Four JEFF interpreters were invited to attend this event, and presented costumed interpretive programs highlighting westward expansion topics. Their 45-minute presentation provided a glimpse of U.S. expansion set in the same geographic location, but at different times in history. Changes in the landscape were reflected through the eyes of a mountainman, frontier artist, soldier, and an overlander's wife. Many of the changes discussed in the program were those which historically prompted the creation of national parks. [112]

Volunteers-In-Parks Program

Volunteers have become an integral part of National Park operations nationwide, due partially to budget cuts, but also in large measure due to the unique background and experiences they bring to their duties with the NPS. Jefferson National Expansion Memorial functioned in large measure because of its hard-working and dedicated volunteer corps, who assisted with all areas of the interpretive operation.

A relatively small volunteer program existed in the Museum of Westward Expansion up until 1984. In that year, Dan Hand, volunteer coordinator for the park, was able to bring in 68 new volunteers in one day. This was made possible because the St. Louis Visitor Center, a city visitor contact site, was moved from its location aboard the Sergeant Floyd, a riverboat on the levee, to an office in the Mansion House on Broadway. The obscure location of this office brought about an alarming drop in the one million visitors per year the organization had claimed. The Visitor Center asked Superintendent Schober if a facility could be built on the Arch grounds for their operation. Since this was not possible, options were explored through which most of the volunteer corps of the Visitor Center would also work at the Arch for part of their volunteer hours. JNEHA Executive Director Ray Breun commented: ". . . So we brought in 68 volunteers in one day. Our volunteer program went from maybe fifteen or twenty or so to almost 100." [113] Dan Hand commented that he conducted intensive training sessions to orient the new volunteers to the park and the NPS. It was an "equally beneficial marriage right off the bat," and within a year of the acquisition of this large core group, 75% of information desk operations were run by volunteers. [114]

The Volunteers-in-Parks (VIP) program continued to expand as the need for volunteers increased. In the beginning stage of a docent program, one volunteer provided interpretive programs twice a week at the Museum of Westward Expansion. [115] However, even a dedicated volunteer program did not guarantee complete coverage at a site. At the Old Courthouse, volunteers were used to interpret and protect the new exhibits during 1986, especially the artifacts in two high-security galleries which featured such items as the 1904 St. Louis automobile and Victorian era furnishings. Many VIPs complained of the extreme humidity and heat in the as-yet non-air conditioned galleries during the height of the St. Louis summer. By summer's end, absenteeism proved that complete volunteer staffing was not a reliable alternative to paid staffing. [116]

|

| Volunteer Mary Reilly staffs the Arch information desk. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

By 1987, 133 VIPs provided 9,800 hours of service to the park, saving the NPS $57,225 in salary costs. This represented a 25% increase in volunteer hours over 1986. A VIP banquet and awards ceremony was held in the Gateway Arch visitor center lobby during National Volunteer Week in April, and an annual VIP Christmas party was introduced in December. A new VIP orientation manual was completed and issued during summer of 1987. [117]