|

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

Administrative History |

|

|

Administrative History Bob Moore |

CHAPTER EIGHT:

The Role of the Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association

A key to the success of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial throughout its years of operation has been the assistance it has received from the Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association (JNEHA). Many of the park's programs were made possible through the money JNEHA raised from the sale of educational materials in its museum shops.

Through a memorandum of agreement with the National Park Service, the Jefferson National Expansion Historical Association was founded on January 13, 1961, with the close cooperation of leading members of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association. Articles of incorporation were filed in Jefferson City, Missouri, establishing the organization, and operations began in April 1961. The first JNEHA staff members were hired in 1968 when the Gateway Arch opened to the public. Only three employees were necessary at that time to manage the operation. Postcards and various publications were the primary sales items, and all profits were put into the memorial's interpretive programs. The Park Service supervised the activities of the museum shop directly, but gave a great deal of latitude to the business manager. When the Museum of Westward Expansion opened in 1976, the staff was enlarged and the association began to play a more active role in the park's interpretive effort, with the beginning of such activities as museum education programs. [1]

Raymond A. Breun was selected as Education Director of JNEHA in 1977. Breun recalled:

I [was selected] on March 14th, 1977 . . . I used to work at the art museum here in St. Louis, and [I] started a thing there called the . . . teacher's resource center. . . . The then assistant superintendent, Norm Messenger, used to come to the meetings of a group that I had started in 1974, . . . the Museum Educator's Round Table of Metropolitan St. Louis. . . [W]hen the Bicentennial came along it was clear that [the local museums] would need to do workshops for school teachers and work with school districts, . . . because it was just getting out of hand for each institution [individually]. So in 1974 we formed this round table, and included libraries and other agencies.

The opening of the museum under the Arch was in August 1976, and the Park Service wanted it to be part of their Bicentennial package for the nation. So the Park Service folks began to take more of an interest in museum education [and] in the educational process. And Norm got the idea of using the Association [JNEHA] as a mechanism to install education in the Park Service. . . Well that's the stuff I had done at the Art Museum . . . In addition, Norm was moving toward getting the Museum [of Westward Expansion] accredited by the American Association of Museums. We had just gone through accreditation at the Saint Louis Art Museum and the two areas of the art museum's program which received special commendation were in the handling of objects and in education.

So Norm wanted to buy some of [my] skills if you will, use the association as a mechanism. The other part that was handy, we did most of those programs at the Art Museum as outside funded programs. We did them through various means that did not include tax money, and he liked that notion as well. We had a series of grants. . . . So, when the position opened here in the association [Norm] asked me to apply, and I got the job. . . . My title was Educational Specialist and it was thought to be analogical to interpretive specialist, but was to be a non-Federal position to allow for the types of things that non-Federal folks can do, but have them done in house . . . He had done some [think]ing over it, and had talked with the then Superintendent Bob Chandler. . . And so the two of them together had [thought] over the need for other ways of doing the kind of business that the Park Service does in an urban environment such as St. Louis. And with the association they had a ready-made vehicle.

When I came I had nothing to do with the sales division at all. All I would do was spend the money. Up 'til 1977 all of the Association positions had been involved with sales, but beginning in 1977 they not only hired me but they also hired the folks that were dealing with what became known as the folklife program . . . [2]

[On the sales side, Norm] was moving the association into a publications program which it had never had. He changed the mixture of items sold. Prior to Norm there were very few books sold, I don't think there were more than a dozen. . . Probably the first items that the association sold going back to 1964 were medallions. . . The first book that the association was involved with . . . appeared in 1965, and has been redone several times, . . . on the construction of the Arch . . . By 1977, that's about all that was in the store, in addition to the American Indian [items]. . .

Norm's motivation therefore was complex. He was able to [see] into the future, he had spent a good deal of time in the museum curatorial side of the house, and was indeed quite interested in that, and also was quite impressed with what the museums did in this town, especially in the educational area. [3]

Superintendent Jerry Schober said of the relationship between JEFF and JNEHA: "I mentioned to Ray that if we were going to have a relationship we . . . don't have to refer to each other as 'them' and 'us.' And as he reformed the sales and the response to the community and all, [the store's] income increased. And I felt we should support those moves, just as long as he didn't go commercial." [4]

Enlargement and Modernization of the JNEHA Museum Shop

By the 1980s, the association had become a vital part of the total park program. As JNEHA grew it took on more responsibilities. In 1985 the museum shop at the Gateway Arch was redesigned and the inventory selectively reduced. This resulted in more efficient operations and an increase in profits by 30%. Breun recalled:

In 1983, after the Charles Russell exhibit, [5] the board treasurer came to me and said, "Have you looked at the . . . profit and loss sheets? And in March of '83 the Historical Association was for all practical purposes in the toilet. The only reason we had any money to pay the staff was that . . . the then business manager and bookkeeper were not paying the bills that were due on the inventory. So we were basically borrowing internally. Then Jack Green [6] came to me and said it's time to look at this . . . I went down to the business office and got copies of all the profit and loss sheets back to 1977, and took them all home [to look at them]. . . So I came back to Jack in May, and I told him that we just didn't have any management on the sales side, and our inventory had grown to be [too] large. . . We had over half a million dollars in books at a time when our sales were under a million dollars. In contrast, our 1991 sales were over three million, and our inventory was only around a $400,000 level. In essence, what was happening was the business manager was taking money which could be used as liquid assets for assisting the park and other purposes, and putting most of it back into inventory, that is, buying stock to sell in the museum shop . . . and in that way trying to keep things going.

So, I basically said you need one head for these two operations, donations and sales. Somebody needs to take a look at the whole thing. And it can't just be the board — you need staff there. And you cannot simply rely on the Park Service. The Park Service management is not going to understand the sales and the accounting that goes into it. . . If we can keep money we can earn interest, then there's more money next year. . . The business manager went away, we didn't have one anymore, the bookkeeper was replaced by a computer . . . and staff turned over. So everything was going on at the same time.

[When] Rick Wilt came here [as Chief of Interpretation from] Carlsbad [Caverns National Park], he said "Let's go spend a couple of days at the Smithsonian to see how they work." I said "That's a heck of a good idea." So he and I took off to Washington for two days. . . and we went from store to store. We talked to people in catalog sales, in accounting, in membership, the whole business. . . I had seen that our sales per square foot were around $1000. And the guys at Smithsonian were already used to using those kinds of numbers. And they said "Well, we do about $800 a square foot." And I looked at them and I said "Oh, well we're already doing more than that." And they said, "Well you shouldn't be here, we should be there." So that insight alone made me stop and think that maybe we were doing some things right, but we needed to take more conscious control over it.

The other thing from our own staff, we never kept the numbers that came out of the cash register that show transaction rates, the amount per transaction. None of that was computed or compared to volume. So, [we could not] look at what other museum shops were doing, and what we were doing, just on a pure statistical basis. . . To me it seemed that the only way you could increase your business was to increase the number of transactions, and the amount per transaction. . . So here I come along as a non-accountant type and I told the accounting staff, "OK, get those numbers." And they didn't have them. And I said "You will go back for all the previous part of this fiscal year, and the year before, and take them right off the cash register tapes. . . And so I gave them a sheet, and I said write them down, and I entered them into my computer at home. So [this is how] I worked out how we could increase our sales.

The original JNEHA museum shop in the Gateway Arch complex, September 1978. NPS photo. So in '83 and '84, when we put this kind of a direction to it, we did two things. First of all, we changed the store design. It was the last store in the world where if you wanted something you had to ask. Non-self-service, in other words . . . It was dark, and dank. It was designed by the same guy who did the museum. [7] No lights. It had a very small little strip sign in front, which half the time you couldn't read because the lights were out, and it was too hard to change the bulbs. . . . It was great at Halloween. But it wasn't any good to make any [money]. And yet despite that, we were still doing almost a million dollars [per year] in sales. So with all that stuff in the way I kept scratching my head and saying, "We can at least triple sales." What people did was go in, buy a postcard and leave. So our transaction rate was under $3 then, and it was $8 in 1991. So even if you do the same number of transactions, you've tripled your money right there.

Jack Green got me in touch with the President of the Board of Famous-Barr [8] who got me to his store design people, and they came down free of charge. We decided that if we re-did the store we could increase the square footage for sales and make the whole store more operational. We went to Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum, Inc. (HOK), and for $12,000 we got our current store design. I spent a quarter of a million dollars to re-do the store, and our first three months' excess profit was equal to that.

While the store was under construction, through the help of the designer at HOK, and with the approval of the Park Service, we bought a 19th century buckboard, and sold [merchandise] off the buckboard outside the theater. . . I brought in some old shelving from home and some old wood and we bought candy jars, and put stuff in them; books and postcards, all kinds of stuff. And we did almost as much business off that silly buckboard as we typically did in January and February anyhow. Plus, the staff found out that people are fun, and if you go self-service they'll talk to you.

Then we computerized the thing so that we used scanners. 'Cause one of the complaints we had gotten in the store was that the store staff was not very friendly. Well, they had two reasons. First of all, they weren't used to talking to people, and the other thing was . . . they had to look at the price and enter it in, and enter the right number, . . . and couldn't talk to anybody. . . Well, I said we'll have the computer look up the number, and a price, and add it up. And then I want you folks to talk to the visitor. All of a sudden we began to get complimentary letters, for the very simple reason that [they] could act as people and let the machine do what the machine does. [We had some initial] arguments with a vendor, [who] didn't want to put bar code on [his] book, and I said "Fine, we won't handle it." And [Superintendent] Jerry [Schober] and [Assistant Superintendent] Gary [Easton] backed me. Well, by God he apologized, and he put the bar code on. . . We were the first store [in the NPS] to have bar code, and now everybody has copied us on that, because it's just a better way of doing business, because you can talk to people. [9]

In 1968, a museum shop was opened in the Old Courthouse, and in April 1987 a full-time person was hired to operate it and assist with basic visitor services and information. [10] Through a redesign of existing space and an increase in the variety of St. Louis-related publications and other sales items, the 1987 gross sales for the Old Courthouse doubled over the previous year's figures. [11]

|

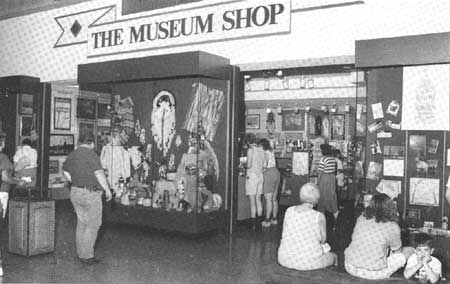

| New JNEHA museum shop in the Gateway Arch complex, 1984. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Donation Expense: Funding Provided to the NPS by JNEHA

In 1982, JNEHA provided $260,040 in funding for park interpretation and educational programs. By 1989, that figure had risen to $447,040, [12] and by 1991, to $994,770. A high percentage of these funds were turned directly back to JEFF by JNEHA. In 1991, for instance, out of gross sales of $2,731,417, 36%, or $994,770, was given in aid to the JEFF. [13]

The number and variety of projects JNEHA money has made possible have been large and diverse. Many of them have been mentioned throughout this administrative history. There were special exhibits such as the Charles Russell art exhibition and numerous others arranged through the traveling exhibit program. The museum education program was financed since its inception by JNEHA. The Folklife Program and festivals were organized by the association. In 1983, the agreement with the NPS was modified as JNEHA assumed the responsibility for operating the Tucker Theater at the Gateway Arch, and subsequently used the funds generated from the admission price to provide association interpreters to keep the Old Courthouse open. [14] In 1985, JNEHA interpreters began working in the Museum of Westward Expansion. [15] Special emphasis programs such as the Victorian Christmas and Black Heritage Month were possible because of association support, as was the production of such publications as the park newspaper Gateway Today and the Museum Gazette series. Because of these growing responsibilities, the JNEHA Board of Directors appointed Ray Breun as its first executive director in 1984, to provide the necessary management for the operation of both education and sales programs. [16]

Specific plans for funding and support for Park Service programs were discussed after the renovation of the store beneath the Gateway Arch in 1985, when sales began to skyrocket. Executive Director Ray Breun remembered:

At the same time we began to talk at the board level of the rate of return to the Park Service and how to manage that. And I said "Based on my analysis . . . if we do it right, our cost of doing business should be no more than around 50% . . . , the cost of supplies, bags, paper, postage, all of the rest of that." And it typically goes between 52 and 48%.

Now, in order to do that you have to have an active product line, where you get much more return, and thus we got into the videotapes, because the return is so substantial, and yet our cost to the visitor is less than in any other store in town. When you pay $29.95 for a tape, the cost to make that tape is less than five bucks. And so we charge basically twenty bucks — $19.95. We also needed an ability to throw away books that weren't selling, so we began to get the inventory cleaned up.

We used the approval process that had been installed in 1980 . . . Where before it had been kind of an adversarial process, it began to be more, "How can we make this work better?" for the good of the visitor. I mean everybody talks that way now. It wasn't that way at one time, believe me.

We established a goal of no more than 50% [for operating expenses]. Selling and office staff, non-donation expenses staff should not exceed 20%. So therefore you're talking about keeping 30%, which is going to be available for product development and donation expense [money given to the NPS]. Donation expense is viewed as an expense item. Donation expense we'd like to keep at about a fourth. So if you do a million dollars in business, $250,000 [goes to the Park Service].

. . . [A]nytime the Park Service doesn't use a buck, I can turn that dollar into a dollar ten. A dollar fifteen. There are various instruments that we have. In August, there's a lot of cash coming in, and not as much going out . . . So when we get into August, then we do some guaranteed investments that are very short-term. A week, three, four-day investments, that give good return. We just basically view the money as a commodity, and you can make it grow. So we did that, and that's what pays for our accounting division. 'Cause I told our controller when I hired her, "Your task is to pay for yourself and your staff on interest." [17]

|

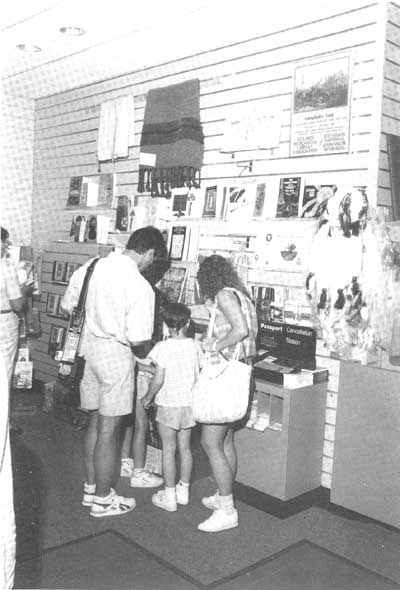

| Visitors browse in the JNEHA museum shop at the Gateway Arch. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

In addition to its direct support, which has amounted to more than $3 million since 1968, the association has also raised funds of nearly $2 million for exhibitions, movies, and educational publications. [18]

Sales Items Controversy

Despite the benefits to the park from JNEHA's activities, there were challenges made by NPS officials from outside the park regarding the items being sold by the association. Ray Breun elaborated:

We had handled T-shirts, and they were constructed to be in line with the postcard program. They were basically walking postcards, as far as we were concerned. And that's an interpretive device that's always been for sale in museum shops. We also had postcards and other sorts of stuff. There are playing cards in the museum, in the cowboy exhibit, and so one of the first things that was added was a deck of cards, that's one of the things that was used by all sorts of folks in the West . . . Well, [our store was] commonly used as an example of what not to do by [the NPS]. [19]

A 1982 memorandum detailed many of the concerns of the Washington office:

The subject of . . . sales [items] at JEFF is not new. Jewelry sales date to the opening of the museum and, despite reviews and critical comments from both the Servicewide and Regional Coordinators, no retractions have ever been made by the association. Such action was in violation of the activity standards and guidelines prior to the Memorandum of Agreement, dated 1977, and are now in violation of NPS-32. [20]

Discussions (at the Servicewide coordinator level) on removing souvenir items date to 1974; lengthy conversations took place in the 1976 association conference when [JEFF] Superintendent Bob Chandler appeared on a theme-related sales item panel discussion. Some items were removed, most notably a glass mug with an "arch" decal. Unfortunately, that mug was replaced with a "higher quality" mug with the "arch" etched into the glass.

The most recent discussion occurred at the park in December during the planning of the 1982 Association Conference. The park and association staffs were adamant that there would be no changes in souvenir sales, "otherwise, a large part of the interpretive program would go down the tubes." [21]

Despite this negative assessment, a 1982 operations evaluation by the Midwest Regional Office praised the role of JNEHA and the items they sold:

A review of sale items carried at the Cooperating Associations Museum outlet indicated that virtually all met NPS criteria for type and purpose. It should be recognized that the Arch Association has long filled a dual role of not only interpretive assistance but quality [sales items] which, in and of themselves, serve as an interpretive remembrance of one of the world's greatest engineering wonders. Recognizing that the Expansion Memorial (the Arch) exists as much for its engineering/architectural marvel as for its commemoration of western expansion, the sale of jewelry and T-shirts that recognize that marvel appear appropriate. There is, without doubt, as much of an interpretive message in a question about "How high is that arch on your T-shirt and how was it built?", as there is in "When did Thomas Jefferson effect the Louisiana Purchase?" . . . As a result, the evaluation team feels that the sale of such items as T-shirts and jewelry depicting the Arch, as long as it is done in a quality manner, is appropriate to the interpretive message of the historic site. It is unfortunate that NPS policy statements identify all T-shirts and jewelry as "unacceptable" items. Perhaps this policy needs some refinement. [22]

In August 1984, Jim Murfin, NPS Cooperating Association Coordinator in Washington, contended that a number of the items that JNEHA sold were not properly theme related — in fact were nothing more than souvenirs — and as such were in violation of NPS guidelines. In defense of JNEHA, Superintendent Schober wrote:

Mr. Murfin contends [that several sales items] are souvenirs, not theme related, and therefore in violation of NPS-32. Mr. Murfin, of course, authored NPS-32. It is now, and has been, the position of previous superintendents that the items contribute to the educational and interpretive theme of the park and, as approved by the Superintendent, are appropriate. [23]

In a 1992 interview, Superintendent Schober elaborated:

They started to press us on certain issues, and they started writing to me saying, "We think you guys are commercializing down there. We don't like it. We want to talk about problems." Well, here's my theory: I don't have problems until I agree to them along with you. And my response was, "I'm not talking about it because I don't have any problems." And so finally I find out that Stan Albright and . . . the head of cooperative affairs, Jim Murfin at that time, was coming out. They never told me. I called Region. I said I didn't think that that was the policy of the service, to come out to a park unannounced. [24]

Murfin proposed that the items in question either be dropped from the inventory, or that the association apply for a concession permit. Neither of these alternatives were attractive to park management. In his 1984 memo, Schober continued:

Were we to agree to the first alternative, and had it been applicable in FY 83, it would have meant a loss to the Association of $580,000.00 in gross sales and $325,000.00 in profits, and ultimately $300,000.00 in donations to the National Park Service for the benefiting public. As regards the second proposed solution, were a concession permit to be applied for, there is no guarantee the Association could be the sole source or retain the permit when it came up for renewal after five years. [25]

In his 1992 interview, Superintendent Schober explained:

There were some things that Ray [Breun] had inherited some years back, when they probably did buy some trinkets. They didn't sell, and we tried to clear our inventory. I said, "Give it away, put it on cut rate." But, I sent it to the Regional Director, and said here's what we're going to do with it, and all of this will be disposed of, we're not doing anything with our T-shirts. A grandparent that comes in, they want something for their grandkids, and they don't want a $70 book. But if it's something that says it's the Arch, and this is a [monument] to a great happening, I don't see a thing wrong with it. There's no concession here, we're not taking from anyone. And it turns into money that puts something even better back; and all of it goes here. This is non-profit; everything they make is turned right back to us. . . . [26]

JEFF counter-proposed "grandfathering" into the agreement with JNEHA the right to sell those items approved by the Superintendent, and the Regional Director agreed:

It is our belief that the Arch represents a unique situation from an interpretive standpoint, and to interpret NPS-32 in regard to the Arch is a difficult task. It is our intention to bring the association into conformance with NPS-32, but we have to do this by taking into consideration the past history of the association and the decisions made by the past and present Superintendents. [27]

As a compromise, an agreement was reached that no new items contrary to NPS-32 would be added to the inventory. This strategy maintained sales and support and provided time to develop new sales items. The issue was finally resolved when the Director of the National Park Service agreed with JEFF and the Regional Office, and approved the arrangement. [28] Superintendent Schober remembered:

I called up [Director of the National Park Service Russ Dickenson] and I said "Hey, I'm going to send you a memo that was sent to [Midwest Regional Director] Chuck Odegaard, and we're going to just put down under there, 'I agree with the procedure,' and you just sign it if think you can." And he said, "Alright." He came in and looked at how the things are taken care of. And he said, "I concur with this," signed "the Director," sent it to Chuck, and sent it to me. Five months later [the Washington Office] said, "We'll be coming down to really get into your problem. This time it's coming from the deputy." . . . When I saw that I just contacted them and said, "Gee, don't you keep up with your correspondence and everything?" And they said, "What? . . . " And I said, "Well, the deputy and the associate for operations are coming down here to work on a problem that the Director of the Park Service says [doesn't exist]. If you refer back to correspondence so and so." [29]

This was the last time that sales items were challenged at JEFF. In the late 1980s and 90s, sales items were carefully screened and evaluated for interpretive value and historical accuracy. A committee consisting of the chief of museum services and interpretation, the historian, and the assistant superintendent of JEFF, reviewed each item sold according to an item selection guidelines memorandum. [30] The process was rigorous, and insured that only items of the highest quality and interpretive value were carried in the JNEHA stores. [31]

Union Station

One of the most unique experiments tried by JNEHA was the creation of an off-site store which would cater to the needs of general visitors and tourists who had an interest in national parks, but was designed to be seen in an environment away from the parks themselves. The store was eventually located in St. Louis' historic Union Station, a railroad terminal completed in 1894 which had been abandoned in the 1970s. Refurbished as a multi-purpose facility by Oppenheimer Properties through their developer, the Rouse Company, Union Station contained a shopping mall with more than 100 stores and restaurants, a Hyatt Regency Hotel, outdoor recreation facilities, railroad memorabilia, commercial office space, and a modern transportation terminal. Union Station was a National Historic Landmark located one mile west of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, patronized by 5 to 6 million visitors annually. [32]

JNEHA Executive Director Ray Breun recalled the thought process which resulted in the Union Station store:

When we were talking about how to reorganize this association to make it more of a benefit to the Park Service in '83, we were toying with the notion of having outlets at off-site locations. We had a request from Famous-Barr at St. Louis Center, and also one at Union Station with the Rouse Company. . . I was interested because it was quite clear to me that we have a corner on the visitor market, but on the local market we don't make any impact.

We were the first to do this sort of thing as far as park sites. Now, museums have been doing this for ages; the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Smithsonian, they've always had huge operations. But we wanted to get "off campus" as well. [33]

Superintendent Jerry Schober continued:

When we first got into it . . . there was a commercial building that came up over here [near the Park]. And they talked about the possible presence of some of the things at the Arch and [maybe] we could sell a few items. But it was something strictly that we did on our own. And the Director of the Park Service [Bill Mott] kept saying "You know, . . . I want evidence of the Park Service in places other than in the parks themselves." He didn't feel that we had the exposure. And you know he was right [about that], . . . we don't market ourselves at all.

We told him, if that's what you want, it could be done here. And so we had a meeting one rainy day at the Clarion Hotel, [myself] and the executive director of Eastern National Park and Monument Association [George Minnucci], which is the largest [cooperating association] in the system. And George said "You know, we need to get some things together, do things for the Park Service and sell things." And . . . I said "I want you to meet Ray Breun," . . . And oh, I'm telling you, these two fellows, all I had to do was get out of their way, and they began to talk about the possibility of Union Station. [34]

Breun continued:

I'd just been hit by a car, so I was still on crutches. . . George was in town and we began to talk about it, and we decided to do it as a partnership. Because Eastern has access to the eastern parks, and because we had to deal with the westward movement, we could sell all kinds of park stuff. . . . We liked the idea of doing it here in St. Louis, because . . . it's in the middle of the country, a [crossroads for visitors]. [35]

|

| America's National Parks Store at St. Louis Union Station. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Superintendent Schober added:

And so their final agreement was, that we operate it, and [Eastern National will] put the produce in, and we'll take care of the staff, and the rent, and all of this, and work their agreements out. We did not go into it to make big bucks. We went into it for the visibility. . . [36]

Breun recalled the planning stages of the store:

When this thing started, George [Minnucci] sent a number of his staff out to be helpful in terms of organizing it, . . . including the sales manager at Chattanooga-Chickamauga; Bill Cole, the manager at Gettysburg, and Shelley Napier from Colonial. [37]

Schober continued:

So we said, hey, [visitors] don't get to see all of the parks, but what if we could get them the information? Now here's where we wanted to carry the idea. We thought it would be good to go to the concessions association and say, "Why don't you put one of those big computers up so we can get information out to the public on the parks?" If you're to visit Grand Canyon, who'll you stay with? The Park Service? No. If you're to visit Yosemite, who'll you stay with? The Park Service? No, it's the concession every time. [So we wanted a computer with National Park information, including accommodations and camping, to be put into the Union Station Store, paid for with various concessionaire's money]. . . . We even went and got an FTS line into the store. For who? The concessioner, so that the public could pick up the phone and make reservations . . . We could've given them all this information, and the biggest benefactor would have absolutely been the concessioner. [38]

Although the Union Station store was an excellent idea which brought millions of people into contact with National Park concepts and management objectives, concessions information and computerized data on the National Parks were not added during the 1980s. In fact, the Union Station store failed to turn a profit. The idea of an off-site store spread, however, to two other areas, in San Francisco and Salt Lake City. Ray Breun elaborated:

In San Francisco it's [run by the] the Park Association at Golden Gate, and in Utah it's Zion's association. In each case they got a better deal from the landlord than we did, but they're just basically following the same pattern. Eastern National has been talking about doing something in Washington, but there's so many associations that they're getting in each other's hair, so I don't know how that will all come out. [39]

|

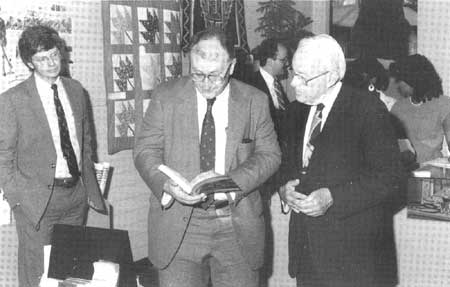

| JNEHA Executive Director Raymond A. Breun with Director of the NPS William Penn Mott, Jr., in the America's National Parks store, 1988. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Interpretation at Union Station

In 1987, a special nationwide interpretive program, called the Union Station Urban Initiative pilot project, was developed at Union Station as another method of bringing the national park concept to St. Louis visitors. A three-month trial period confirmed the great potential for reaching a major metropolitan audience with information on the NPS. Although visitor statistics were difficult to keep given the crowded circumstances in the shopping mall, the project made more than 9,000 significant contacts through either formal or informal programs. Superintendent Schober recalled:

We hit upon the idea of [representing] every region; we went to the Regional Directors, and said "We're going to put on demonstrations that represent other regions of the Park Service, and you have the opportunity, if you want to participate, to say, 'Ah, well, I'll just send anybody,' or, if you want your region to come off looking really good, you'd better send some sharp suckers down here." Because we found out they'd had 10 million visits at Union Station in an 18-month period.

Representatives of eight regions and twelve individual parks took part in the program between June and September 1987. A total of fifteen rangers came to St. Louis with a wide range of experience, interpretive methods and styles which significantly contributed to their success. Their work was characterized by enthusiasm and flexibility, qualities that proved extremely beneficial. [40]

Under the direction of the JEFF staff, programs varied from living history, to formal interpretive programs, to skills demonstrations. After gaining the attention of visitors, each of the interpreters effectively conveyed their message on the scope and diversity of the National Park System. [41] Living history programs included presentations about one of Abraham Lincoln's neighbors; two Civil War soldiers from opposing sides, and a U.S. Dragoon from the 1840s. Formal programs covered such topics as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the legacy of Carl Sandburg, and NPS areas in the West. Park Rangers from Carlsbad Caverns National Park presented one of the most effective programs of the project, rapelling from the rafters of Union Station in a demonstration of climbing skills. These demonstrations gathered large crowds for a talk on ground water quality and other resource management concerns in cave areas. [42]

|

| Park Rangers Gary Candalaria and Karen Gustin tell visitors to St. Louis' Union Station about the National Park System. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Superintendent Schober recalled:

Bill Mott said, "To do those ranger shows and all of that, I'll put up one half, Jerry. You and the Region put up the other half." Because this hadn't been something we'd programmed for, that sounded reasonable. He got back to Washington, and they were sitting in with the then head of concessions . . . and they said "Oh boy, having that store as the focal point, man, the concessionaires are going to take you apart," and they really worked on the Director. And the Director never sent us any funding. But they did send one directive: Don't do those ranger programs anywhere around . . . your association store. Now what was worrying them was that it looked like you were making a profit in that store. . . . Concessions who would never sell an association book because it didn't have enough mark-up, now were becoming jealous of associations. The concessions figured the associations were making money and that they ought to have those opportunities. . . . And you know what was funny? The visitors that were looking at it always said "Why didn't you put [your programs] on next to your store down there? That would sort of compliment it." [43]

Following the demise of the Urban Initiative Project on a national scale, JEFF continued with a program staffed with its own interpreters, working on a daily basis during the summer months, June 24 through September 2. This intense off-site program, coordinated with Union Station management, JNEHA and Eastern National Park and Monument Association, highlighted various areas within the National Park system through the use of special interpretive themes, such as wildland firefighting, hats of a park ranger, predators (including humans) in the national parks, and biodiversity. Rangers also assisted the public with questions concerning the NPS, including vacationing and camping in and near NPS sites. [44]

The program was expanded on several occasions for special events. On August 25-26, 1990, JEFF sponsored a special event at Union Station commemorating the 74th anniversary of the National Park Service. Programs included canoe demonstrations by park rangers from Ozark National Scenic Riverways, living history by a volunteer group of African-Americans recreating the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, and a display of birds of prey by a local raptor research center. This project enhanced the role of the America's National Parks store as a source of information about the National Park System. [45]

|

| Park Rangers from Carlsbad Caverns National Park demonstrate rapelling from the rafters of Union Station in 1987. NPS photo by Al Bilger. |

Beginning in late spring of 1991, and running through the end of the year, JEFF rangers expanded the program of informal interpretation at the America's National Parks Store to seven days a week. Programs were also conducted on weekends (when staffing allowed) during the off-season, and special Black History Month programs were conducted during February. Through these special details, rangers were able to increase public awareness and appreciation of the National Park Service and its mission. This aspect of the operation received greater emphasis when the 75th anniversary of the NPS was celebrated by rangers from the Grand Canyon and Ozarks. Joining the JEFF staff, these guest rangers were stationed at three different locations within Union Station on August 25, 1991. Nearly 28,000 public contacts were made during 1991. [46] The intensive program at Union Station was the fulfillment of the original interpretive purpose of the off-site store as outlined by Director William Penn Mott, and the dissemination of national park information to non-traditional park visitors realized the original concept of Ray Breun and Jerry Schober.

The Future

Superintendent Jerry Schober summarized:

[JNEHA] has set a number of precedents within the service. They do all sorts of good services, and to me, these are partnerships. You talk about partnerships with the outside, [these are] partnerships with our association. And they should be tools where we can use each other in a way. You might say, well, how does the association get anything from you? Their mere existence means they've got all these jobs. And all of us have some mission in life, and theirs is to raise the funds, so that other things can go on, and so that you can pay salaries. So there's a complementary thing with all of us, and yet we share that biggest mission, which is why there's a spark here. So I don't think we've touched the potential of what could be there and I don't think the Park Service knows what that potential is. [47]

During the 1980s, JNEHA expanded their sales operations within Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, opened an off-site store, funded important projects within the park and became heavily involved in support for educational and interpretive programs. The decade was a period of transition, growth and change for the organization, which became an essential part of the Memorial's operation. The symbiotic relationship between the park and JNEHA included many unique aspects rarely seen within the National Park System, and promised great innovation and continued experimentation during the 1990s.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

jeff/adhi/chap8-2.htm

Last Updated: 15-Jan-2004