|

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

Administrative History |

|

|

Administrative History Bob Moore |

CHAPTER THIRTEEN:

Unusual Events and Occurrences at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

As the facts and figures in this administrative history have shown, the Gateway Arch is a unique place. Because it is different, unusual, and looms so large as both structure and symbol, the urge to challenge, "conquer" or use it for the personal exhilaration and/or aggrandizement of individuals has been strong since it was built. The Arch receives a tremendous amount of attention on its own, and, it is reasoned, has the potential to draw attention to an individual or a group in the same way. The administration of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, aware of the symbolic nature of the Gateway Arch and the potential for misrepresentation of bureau, department, and governmental aims and goals through its use/misuse, have been extraordinarily careful about permissions granted to individuals, groups, and corporations.

Some uses of the Gateway Arch have been impossible to control, for example, the unfortunate temptation of aircraft pilots to fly between the legs of the structure. The completed Arch was less than a year old when the first plane flew through on June 22, 1966. Two planes did it in December 1969, on the 12th and 17th. Other flights were made on April 16 and October 8, 1971, November 2, 1977, January 30 and February 5, 1981, and February 26, 1982. By far the most dangerous, the 1977 flight was detailed by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. The pilot flew at night, without lights, proceeding up Market Street at an altitude of 50 feet, "just above the street lights," through the Arch and on across the river. The danger to people in the Arch, on the grounds, on the streets and in other buildings was very great. A helicopter flew through on April 6, 1984; the pilot was identified and brought to justice by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). This flight made a total of eleven confirmed fly-throughs prior to 1991. [1]

The other major way in which people tried to "conquer" the Gateway Arch was by scaling it and/or parachuting from it. The first instance of this behavior ended in tragedy. On Saturday, November 22, 1980, at approximately 8:55 a.m., Kenneth Swyers of Overland, Missouri, "was seen parachuting above the Gateway Arch. It appeared that Swyers landed on top of the Arch and that he was thrown off balance when the wind caught his parachute. Swyers' parachute deflated and [he] fell down the North Leg of the Arch. Approximately [half-way] down Swyers attempted to deploy his auxiliary parachute, however it failed to open and Swyers landed on his head on the concrete terrazzo. Swyers was pronounced dead at the St. Louis City Hospital at 0950 hours." [2]

The 33-year-old Swyers requested permission to make a parachute jump in the vicinity of the Arch on August 21, 1980, which was denied by Charles Ross, special assistant to the superintendent. Swyers watched a television program the night before his death which showed daredevil acts of parachute jumping. Swyers was himself a parachute enthusiast who had made more than 1,600 jumps, and on the morning of his death, he left a note for his wife to come to the Arch to photograph his jump. Few park employees or visitors were on the grounds before 9:00 a.m. in late November when Swyers made his jump. Park Technician Lisa Hanfgarn, hurrying to get to work on time, thought she saw an object fall down the North Leg of the Arch as she entered the doors to the complex. She reported this to Seasonal Park Technician Liz Schmidt (of the law enforcement division), who was monitoring the north entrance doors. Schmidt went outside to discover the body of Swyers lying in the midst of his parachutes, and immediately radioed to law enforcement rangers requesting assistance, an ambulance and the city police. Two St. Louis city policemen, who witnessed the jump from Wharf Street, arrived on the scene and documented the fatal injury to Swyers. An ambulance was on the scene by 8:59 a.m. Mr. Swyers' wife was on the grounds at the time of the accident and saw her husband fall to his death. She came forward at the accident scene, viewing her husband's body and eventually covering his face with his parachute. A large crowd gathered, composed of visitors, police and medical personnel. Park Technician Schmidt later testified that the weather was blustery, cold and windy, and that it was not a good day for a jump, near the Arch or elsewhere. The FAA was immediately notified, and an investigation eventually turned up the pilot who ferried Swyers over the Arch to make his fatal jump. As a result, Richard Skurat of Overland, Missouri had his pilot's license suspended for 90 days by the FAA in December 1980. [3]

Other requests or attempts at similar stunts, despite the tacit warning of Mr. Swyers' tragic death, continued throughout the decade. At 7:15 a.m. on October 29, 1983, Ranger Roger Cleven noticed a man trying to climb the north leg of the Gateway Arch, wearing suction cups on his hands and feet. The man had ascended about 20 feet, but Cleven was able to talk him out of continuing. The following day, this same man, 21-year-old David Adcock of Houston, Texas, scaled the Equitable Building in downtown St. Louis dressed in a blue suit and blue fright wig. Adcock intended to parachute from the building, but attracted such a crowd, including St. Louis police and fire companies, that after scaling the building he rapelled to the ground instead. Adcock used the alias "Skip Stanley, the Blue Bandit." He was apparently quite serious about climbing the Arch; he had given a batch of T-shirts to vendors outside Busch Stadium (there was a football game on the Sunday of his climb) which read "1983 Arch Climb." [4]

In February 1986, Hollywood stuntman Dan Koko requested permission to make a free-fall jump from the top of the Gateway Arch on the 4th of July, during the Veiled Prophet Fair. Koko held the world record for successfully jumping free-fall (into large cushions without a parachute); he jumped from a height of 326 feet off a Las Vegas hotel roof in 1984. Permission for the jump was denied by the park. [5]

In addition to stunts, the Gateway Arch has been a magnet for the famous. Due to the security considerations posed by its enclosed space, however, visiting U.S. Presidents have so far not been allowed by the Secret Service to travel to the top. On August 24, 1979, President Jimmy Carter made a speech on the St. Louis riverfront, immediately after disembarking from the Delta Queen riverboat. In his speech, the President recognized the 10-millionth paid visitor to ride the tram to the top of the Gateway Arch. [6] Presidents Gerald R. Ford and Richard M. Nixon arrived on the grounds by helicopter, to keep appointments in other parts of town. Then-Vice President George Bush visited the park for the VP Fair in 1988. President Reagan spoke at a rally on the Arch grounds on November 4, 1984. None of these Presidents entered the visitor center complex or rode to the top of the Arch, however. [7]

The only President or former President to ride to the top of the Arch was Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. Since it was Eisenhower who authorized construction of the memorial on May 17, 1954, his visit was fitting in many ways. [8] On November 13, 1967, Gen. Eisenhower was scheduled to speak in St. Louis at a fundraising dinner for Congressman Tom Curtis. Eisenhower was returning home to his Gettysburg, Pennsylvania farm, and had a rigid itinerary for his St. Louis visit. Before the dinner, a trip to the new Gateway Arch was planned. This involved a brief 15-minute stop, during which the general could look up at the monument and chat with a reception committee from the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association. The committee presented Gen. Eisenhower with several mementoes (still in the collection of the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas), including a replica of the Arch, a JEFF medallion, and a brochure. [9] Eisenhower was also greeted by Superintendent LeRoy Brown and Assistant Superintendent Dr. Harry Pfanz, who had met the general during the time Pfanz was historian at Gettysburg National Military Park. [10]

Gen. Eisenhower arrived an hour ahead of schedule, and at some point decided to take a ride to the top. [11] It was after closing time, and no visitors were in the complex. Eisenhower was taken into the Arch visitor center by LeRoy Brown and Dr. Pfanz, who accompanied him to the top. Dick Bowser, the designer of the Arch tram system, was also tapped to help with the trip, as special arrangements had to be made for the general. Because of Eisenhower's heart condition (he was 77 years old at the time), he did not walk down the stairs to the load zone, but a tram was brought to the upper level, and Eisenhower entered the first capsule through the maintenance access door. [12] The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that Eisenhower "called it a 'remarkable experience,' but said he was sorry he was unable to see the entire city because of cloudy weather." The general enjoyed his visit tremendously. Curious and intrigued by technology, he stayed much longer than his itinerary allowed. Dick Bowser pronounced the general a "very nice man, not like some

|

| Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. Courtesy Eisenhower National Historic Site, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. |

VIPs who have come through the Arch. He kept saying something like 'this is very unusual' or 'this is very unique.'" [13] As a postscript to the story, Eisenhower's military aide, Col. Robert Schultz, remarked in a letter of November 24, 1967, that the visit to the Gateway Arch "had loused up the whole schedule" of the general's visit to St. Louis. [14]

Many famous people, politicians and celebrities have visited the Gateway Arch. In addition to those covered in the chapter on the VP Fair in this administrative history, the Arch has also played host to the Vienna Boy's Choir, [15] entertainer Johnny Carson, and His Royal Highness Charles, the Prince of Wales, who not only toured the Arch complex and rode to the top, but also attended a reception in his honor at the Old Courthouse. Prince Charles' visit, on October 21, 1977, was sponsored by the St. Louis Chapter of the English Speaking Union and the Council on World Affairs. [16]

|

| H.R.H. Prince Charles of Great Britain in the Museum of Westward Expansion, October 1977. NPS photo. |

Marine environmentalist Jacques-Ives Cousteau docked his famous vessel, the Calypso, on the Mississippi below the Gateway Arch in 1983. Cousteau stayed in St. Louis for three days, promoting an awareness of river ecology. [17] Of interest to the Park Service and the site were the visits of Conrad Wirth, 85-year old former director of the NPS, [18] and Susan Saarinen, daughter of architect Eero Saarinen. [19]

The JEFF Public Affairs Office received several unusual requests each year. Brief examples of these included a children's author who wanted to take the hero of his books, "Josh the Wonder Dog," to the top of the Arch; [20] an offer to clean and polish the entire stainless steel surface of the Arch with a product called Primo Polish; [21] the suggestion that the Bulgarian-born artist Christo "wrap" the Arch with cloth as he had other landmarks; [22] and a request that the American flag be placed atop the Arch, proposed by one American Legionnaire and rejected by the American Legion Central Executive Committee. [23] All of these requests were denied. Throughout its history, it has been the goal of the Park Service and its managers to maintain a dignified image for the Gateway Arch, as a symbol of the country's westward expansion.

|

| A rally for President Gerald Ford was held on the Arch grounds, October 29, 1976. NPS photo. |

Many symbolic events were allowed to take place on the grounds. The Gateway Arch was the St. Louis area centerpiece for the "Hands Across America" celebration on May 25, 1986. At 2 p.m. local time, people across the United States linked hands in a dramatic gesture to fight hunger and homelessness. [24] Another unforgettable scene took place as the Olympic Torch arrived in St. Louis and was carried past the Arch by gold medal winner Wilma Rudolph on June 6, 1984. The torch was on a 9,000 mile journey from New York to Los Angeles for the 1984 summer games. [25] Two religious zealots, an Englishman named John Buckner and American Robert Spelman, trekked across the United States carrying a 140-pound cross in 1984. They were photographed on the Arch grounds on September 19, 1984. [26]

Rallies of all kinds have taken place on the grounds, from a pro-defense rally featuring a speech by the Rev. Jerry Falwell in 1984, to a group participating in a world-wide event protesting "nuclear insanity" in 1983. [27] "Owners and sellers of satellite dishes, frustrated by what they say is a growing prejudice against them," rallied under the Gateway Arch on March 4, 1986, "in preparation for a protest march on Washington, D.C." St. Louis was the rendezvous point for satellite dish owners and distributors from throughout the Western United States. [28] In a more sobering political rally, Koreans demonstrated against the Soviet Union after the downing of a South Korean passenger plane in 1983. [29] These rallies illustrated the fact that, less than ten years after its completion, the Arch was accepted as a national symbol and adopted as a place where people from St. Louis and the nation felt they could make a statement about national and international issues.

The Arch trams were used in a special offer made by the Monsanto Corporation to fight the infant disease "crib death," or sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). During October 1986, Monsanto donated 20 cents for every person who rode the Arch tram to SIDS Resources, Inc. This fund-raiser provided for 40% of the SIDS resources education programs for 1987. [30]

In an unusual educational application of the Gateway Arch, Ken Smith, a civil engineering teacher at Florissant Community College, led an annual walk up the 1,076 steps of the Arch with his students, who learned at first hand about the construction and mathematics of the structure. Smith led his first trip up in 1971, and continued an unbroken annual pilgrimage to the interior of the Arch for 13 years, with the exception of 1983, when budget problems on the part of the NPS canceled the trip. [31]

|

| An anti-ERA rally on the Arch grounds, 1983. Photo courtesy John Weddle. |

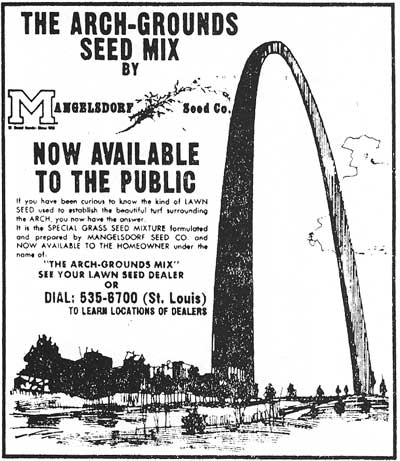

The Gateway Arch has been used repeatedly in advertising. Even before its completion in 1965, the Arch appeared on all manner of objects and business logos in the St. Louis area. [32] The "Arch-Grounds Seed Mix," distributed by the Mangelsdorf Seed Company, sported an image of the Arch on the package and proved very popular, especially in the St. Louis area, where the carefully-kept Arch grounds were much admired. [33] The Arch was featured in many local television commercials, most notably by the appliance-selling Slyman Brothers. Through the use of a chroma key and blue background, the brothers were made to look as though they were perched atop the Arch. A carpet discount house in Illinois named "Queen O' Tiles" featured its spokespersons on a "flying carpet" done in much the same manner. But the Gateway Arch has not been featured in local commercials alone. In 1990, a request from a Japanese company, Asahi Glass, involved placing a lightweight replica of the statue "The Thinker" by Rodin atop the Arch for a television commercial. The request was denied, although the company used shots of the Arch in their ad. [34]

|

| Advertisement for "Arch Grounds Seed Mix." |

As the landscaping was completed and the trees began to mature, the grounds of the Gateway Arch became important as a lunchtime walker's and runner's haven to those who worked downtown, an escape from the pressures of the office and the claustrophobic encirclement of downtown buildings. Recreationists even created and photocopied homemade maps of the Arch grounds, which plotted the distances of each path and showed ideal runner's routes. "Around the Arch, we regulars walk resolutely," reported one of them. "By now, we know each other's first names, employers, marital status and opinions. . . . Awhile ago, I stopped one of the rangers and gave him the diagram so he could tell people how far as well as how high. 'Well, thanks. If anyone asks, I'll know now,' he said. [The ranger] stared up the great, glinting sculpture. 'One lady just stopped me the other day and told me she thought it looked like a giant striding into the future.' The woman concluded her article by stating: "Nice job, Eero, nice job. You captured us perfectly." [35]

These words seem to summarize the feeling a human being has when visiting the Gateway Arch. It is bigger than life. It changes its appearance with the weather, time of day, and the seasons. It is a unique symbol, seen in different ways by different people, and used — most of all used. The Arch is at once local, national, and international. Jefferson National Expansion Memorial provides a stage for so much of the pageant of humanity within St. Louis' urban grid, whether it be daily life, annual events, or the interpretation of the history of St. Louis, the West or America. Jefferson National Expansion Memorial is more than a park, a historic site, or a monument. It is an experience.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

jeff/adhi/chap13-2.htm

Last Updated: 15-Jan-2004