|

Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve Louisiana |

|

NPS photo | |

Louisiana's Mississippi River Delta conjures images of a spirited culture and places of haunting beauty. It is a world shaped by a dynamic, centuries-old relationship between humans and a still-evolving land. Here a succession of peoples has both altered and adapted to the environment as they interacted with other cultures—changing and being changed. Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve tells the story of this land and its culture that together show one of the most interesting faces of the American experience.

Cajun Mardi Gras—Costumed horseback riders begging farmers for a chicken destined for the communal gumbo; egrets floating over the marshes of the Barataria estuary, its expanse broken by scattered fishing camps on stilts; the rampart at Chalmette Battlefield, where it is easy to imagine 5,000 British soldiers charging into a withering barrage of shot and shell; New Orleans, where a stroll feeds the senses—the keen aromas of gumbo or hot beignets drifting from French Quarter cafes, staccato tap dancing in the street, the endless trove of goods at the French Market, the glittering Mississippi seen from atop the levee. And the music—one is borne through the day on music, from jazz clubs on Bourbon Street to a Cajun two-step at the Liberty Theatre in Eunice; from accordion-driven zydeco to street-corner blues. How did such an endlessly fascinating place come to be?

First there Was the land, the creation of the Mississippi River. At the end of its journey, the river deposits sediment scoured from 40 percent of the continental United States. The delta is a restless interplay of land and water: treeless marshes, distributary channels, slow-moving bayous, forested natural levees, freshwater swamps, and barrier islands. A small swath of the delta within the Barataria Preserve encompasses some of these natural features and a history of human activity. American Indians settled this land as it formed some 2,500 years ago. Beginning in the 1720s European settlers and enslaved Africans took their place among the Indians, inscribing on the face of the delta—alongside ritual earthen mounds and ancient shell middens—plantation fields, artificial levees, logging canals, trappers' ditches, and oil pipelines.

Just as soil washed from a huge watershed shapes the delta, people from all over the world shaped the remarkable delta culture. After founding the Louisiana colony in 1699, France laid down the basic cultural rhythms. Religion, language, law, architecture, music, food—all echo their French origins. Other groups contributed different rhythms, different overtones: Chitimacha, Houma, and other tribes; Canadian French; German settlers. Enslaved people from West Africa contributed their labor, agricultural practices, and culture. During the Spanish rule of Louisiana from 1763 to 1800, Spanish-speaking Isleños (Canary Islanders) and French-speaking free people of color from the Caribbean began arriving in the delta. French Acadians, driven from Nova Scotia by the British, settled the bayous and prairies.

Facing an influx of Americans and immigrants after the Louisiana Purchase, French-speaking, mostly Catholic, residents called themselves "Creoles" to distinguish native from newcomer. At the Battle of New Orleans, diverse groups found common cause under Gen. Andrew Jackson, driving back the British in the last battle of the War of 1812. The victory secured the Louisiana Territory for westward expansion, bolstered national pride, and gained the United States respect abroad.

Before the Battle of New Orleans, Jean Lafitte commanded a large confederation of smugglers and privateers based in Barataria Bay. Though long hounded by American authorities for smuggling slaves and goods, he joined forces with Jackson in the battle, providing men, artillery, and information. Pardoned for his service, he slipped from the pages of history and lingers only in delta legend.

Creole and Cajun: People of the Delta

Creoles and Cajuns—names romanticized, stereotyped, and misunderstood. Visitors are deluged with the words, all too often used to sell something rather than convey meaning about a people and their culture. Who are Creoles and Cajuns, and what do the names mean? Today various groups in Louisiana describe themselves as Creole—often claiming exclusive rights to the term. All have legitimate ties to that heritage. The distinction dates to the early 1800s, when Louisiana ceased to be a European colony and became a possession of the United States. Creole originally meant "born in the New World." For many natives, whether of French, Spanish, African, or German heritage, it meant "us"—French-speaking, native born. "They" were Americans or European immigrants arriving in droves at the port of New Orleans, speaking not French but English or their native tongues. They were outsiders, bent on changing the Creole way of life.

Times change, meanings blur, and people's sense of themselves evolves. But "Creole" retains its old meaning as an adjective describing the food, music, and customs of those areas of Louisiana settled during French colonial times. In a sense, despite the overwhelming Americanization of Louisiana, the original Creoles won. Visitors come to experience Creole, to experience what sets this place apart: Mardi Gras and red beans, jazz and joie de vivre. Whoever came here—English, African, Irish, Italian, Chinese, Filipino, Croatian, Honduran, or Vietnamese—contributed to Creole culture and in turn were shaped by it.

From their arrival in the late 1700s the Acadians, or "Cajuns," were a people apart. Mostly small farmers and craftspeople, they settled in the bayou country, where their isolation was compounded by their distinctive dialect and their fierce loyalty to family and place. Urbane New Orleanians saw them as quaint and rustic, subjects of humor. Driven by hard times to seek other livelihoods, Cajuns pioneered new ways to live off the bounty of the delta landscape. In this they were joined by other groups who helped shape the culture we now know as Cajun. No longer isolated, their culture is admired worldwide—even in New Orleans.

Shaping a New Land

The Mississippi River delta is some of the youngest land in North America. The deltaic sediments that underlie the New Orleans region are less than 4,000 years old. Natural processes—deposition of new sediment, erosion, subsidence (settling of sediment)—maintained a healthy equilibrium between land and water at delta's edge. Human engineering has upset the balance, blocking sedimentation and increasing coastal erosion. Rising sea levels due to climate change are accelerating the loss—a football field's worth of land every 45 minutes.

Before artificial levees and jetties, the Mississippi and its distributary branches built land in two ways. Spring floods overflowed river banks. The heaviest particles of the waterborne sediment settled on the bank; the rest spread out gradually. This process created natural levees along the flanks of the waterways. The land. highest near the river, sloped gradually down the back of the levee to freshwater swamps and finally marshes. The soils got wetter as the levee sloped downward. Oaks and other hardwoods dominated the highest ground; maple, ash, and palmetto the backslope; baldcypress and water tupelo the swamp; with grasses, sedges, and rushes in the marsh.

The second process of delta-building occurs at the mouth of the river, where great plumes of sediment are deposited in the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico as the current slows. The deposits build up into mud flats, eventually colonized by wetland vegetation. The river tends to wander and change course over this flat area, always seeking the shortest route to the sea. It often forks into two or more distributary channels within one delta. The new distributary forks sometimes capture the main flow from the old channel. In this way new deltas are built. As old deltas wash away, their sediments are reworked by Gulf waves and storms into barrier islands and beaches. Over the last 3,500 years the Mississippi has created five major deltas, the newest only 500 years old.

The Six Sites of Jean Lafitte

Exploring Acadiana

Eunice

Prairie Acadian Cultural Center utilizes exhibits, Cajun music and

dancing, cooking demonstrations, and live radio programs at the Liberty Theater

to interpret the culture of the Acadians who settled the southwest Louisiana

prairies.

250 W. Park Ave.

Eunice, LA 70535

www.nps.gov/jela/Prairieacadianculturalcenter.htm

Lafayette

Acadian Cultural Center presents exhibits, films, programs, and boat

tours of Bayou Vermilion to share the history, customs, language, and

contemporary culture of the Acadians who settled Louisiana.

501 Fisher Rd.

Lafayette, LA 70508

www.nps.gov/jela/Acadianculturalcenter.htm

Thibodaux

Wetlands Acadian Cultural Center interprets the bayou Acadian culture

with music, exhibits, art, boat tours of Bayou Lafourche, craft demonstrations,

and other activities.

314 St. Mary St.

Thibodaux, LA 70301

www.nps.gov/jela/Wetlandsacadianculturalcenter.htm

The New Orleans Area

French Quarter

French Quarter After founding New Orleans on a bend of the Mississippi

River in 1718, French colonists laid it out in a neat grid. The distinctive look

of the 66-block Vieux Carre (old square) is due to its architectural styles,

developed in New Orleans in the 1700s and 1800s. The St. Louis Cathedral, the

heart of the district, is flanked by grand Spanish colonial public

buildings.

In 1856 the city erected the statue of Andrew Jackson, hero of the Battle of New Orleans and namesake of the public square. The Vieux Carre retains much of its character today because it is among the nation's oldest protected historic districts.

Visitor center exhibits, walking tours, films, music

performances, folklife and cooking demonstrations, and ranger talks highlight

the history and culture of New Orleans and the Mississippi River delta.

419 Decatur St.

New Orleans, LA 70130

www.nps.gov/jela/Frenchquarter.htm

Directions to Barataria Preserve from French

Quarter

Take Magazine St. to Calliope St. Turn right onto ramp for "Mississippi River

Bridge" (Business Hwy 90). Take exit 4B. Turn left at second light onto

Barataria Blvd. Stay on it for nine miles until you reach the preserve.

Barataria

Barataria Preserve is made up of 24,000 acres of marsh, swamp, and

hardwood forest. The preserve offers a visitor center, environmental education

center, ranger programs, walking trails, waterways, and picnic areas.

6588 Barataria Blvd.

Marrero, LA 70072

www.nps.gov/jela/Baratariapreserve.htm

Chalmette

Chalmette Battlefield and National Cemetery offers living history

programs, ranger talks, and visitor center exhibits and films. The battlefield

is the site of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans; the Civil War-era national

cemetery holds more than 15,000 graves of American troops from the War of 1812

to the Vietnam War.

8606 West St. Bernard Hwy.

Chalmette, LA 70043

www.nps.gov/jela/Chalmettebattlefield.htm

About Your Visit

(click for larger map) |

Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

419 Decatur St., New Orleans, LA 70130

www.nps.gov/jela

Contact park headquarters or individual park sites for information on days and hours, programs, drive time between sites, and volunteering. There are no camping facilities, food, or lodging in the park; these can be found in nearby communities. Public transportation is very limited; contact the park or see the park website. See the park website for information on firearms regulations and other special uses.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to a visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check the park website.

For Your Safety In summer drink plenty of fluids and avoid exposure to sunlight for long periods and at midday. Avoid small mounds of dirt; biting fire ants may live there. In Barataria Preserve, stay on trails; be alert for venomous snakes; don't approach or feed wildlife (especially alligators); use insect repellent.

Source: NPS Brochure (2017)

CHALMETTE BATTLEFIELD

Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson's stunning victory over experienced British troops in the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, was the greatest American land victory of the War of 1812. Although the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war, was signed in Belgium on December 24, 1814, it was not ratified by the United States until February 1815, so fighting continued. This battle preserved America's claim to the Louisiana Territory, prompted migration and settlement along the Mississippi River, and renewed American pride and unity. It also made Jackson a national hero.

The War of 1812 was fought to secure US maritime rights, reduce British influence over American Indians on the western frontier, and pave the way for the US annexation of Canada. Neither side had much success in the early days of the war.

Great Britain, battling Napoleon's armies in Europe, could spare few troops to fight in the US; most were sent to defend Canada. America had few victories, most of which were at sea. When Napoleon was defeated in the spring of 1814, the War of 1812 changed dramatically. Thousands of battle-tested British troops sailed for the United States for a three-pronged attack that included a full-scale invasion from Montreal; skirmishes and raids on Washington, DC, and Baltimore; and an attack on New Orleans.

The first advance ended when the British lost the Battle of Lake Champlain in September 1814. During the second, the British invaded Washington and burned the White House and the Capitol, but Fort McHenry in Baltimore held off British ships, ending this attack. The third began in late December when British Maj. Gen. Sir Edward M. Pakenham led a 10,000-man army overland from Lake Borgne to attack New Orleans. The capture of this important port was Britain's main hope for exacting a favorable peace settlement from the Americans. By controlling the mouth of the Mississippi River, England could seriously threaten the economic well-being of the entire Mississippi Valley and hamper US westward expansion.

Defending New Orleans were about 5,000 regular US troops, state militiamen, and volunteer soldiers, including Jean Lafitte's Baratarian pirates. On December 23, when British troops landed nine miles downriver from New Orleans, Jackson halted their advance in a fierce night attack. The Americans then withdrew behind the banks of the Rodriguez Canal.

The Rodriguez Canal bordered one side of the Chalmet plantation, running between the Mississippi River and a cypress swamp. Jackson's plan was to force the British to march through the stubble of harvested sugarcane fields toward his troops. The Americans enlarged the canal and filled it with water, built a shoulder-high mud rampart thick enough to withstand cannon fire, and waited for the British to attack.

Pakenham tested the Americans' nerve and firepower with a reconnaissance on December 28 and again on January 1. When these efforts failed, he knew he must either withdraw, risking an American attack from the rear, or assault Jackson's rampart. Relying on good leadership and his experienced soldiers, he chose to attack.

On January 8, 1815, Pakenham sent 7,000 soldiers head on against the American position. The British concentrated their attack on the rampart's ends, assuming those were the weakest points, but the fire from Jackson's artillery and small arms tore through their ranks with devastating effect.

As the British assault against the American rampart near the swamp begin to falter, the 93rd Highlanders were ordered to march diagonally across the battlefield from their position near the Mississippi River. The regiment was exposed to raking fire and suffered heavy casualties. Pakenham rode forward to rally his men and was mortally wounded. Many other high-ranking officers, including Maj. Gen. Samuel Gibbs and Maj. Gen. John Keane, were killed or wounded. Although a small force continued a brave advance. Gen. John Lambert, the surviving British commander, ordered a retreat.

The Battle of New Orleans lasted less than two hours, with the major fighting confined to about 30 minutes. More than 2,000 British troops were dead, wounded, or taken prisoner; American casualties numbered fewer than 20. Within days the British withdrew, ending the Louisiana campaign.

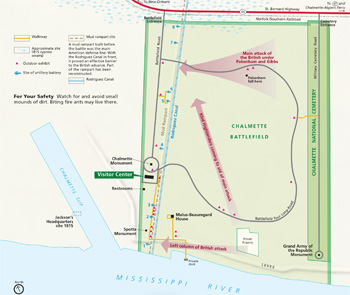

Touring Chalmette Battlefield

(click for larger map) |

The Battlefield Tour

Start at the visitor center

to see displays, maps, interactive exhibits and films that explain the

importance of Louisiana and the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812.

Outside exhibits, along the walkways to the batteries, the Malus-Beauregard

House, and the 1.5-mile Battlefield Tour Loop Road, tell more stories about the

people and the land before, during, and after the battle. Check at the visitor

center for tours and program schedules. Special programs for groups can be

arranged in advance.

American Line of Defense On January 8, 1815, eight artillery batteries, a mud rampart, and Rodriguez Canal provided the main line of defense for American troops defending New Orleans from British invasion. The Battle of New Orleans pitted Americans, who were outnumbered and less experienced, against war-hardened British veterans. Outdoor exhibits along the rampart and Rodriguez Canal describe American troops, their weapons, the 1815 landscape, and the last major battle of the War of 1812.

British Strategy Maj. Gen. Sir Edward M. Pakenham's goal was to capture the port of New Orleans and gain control of the Mississippi River. Outdoor exhibits along the Battlefield Tour Loop Road explain the British battle plan that called for attacks along the river, against the American rampart near the swamp, and on the west bank. Other exhibits explain the British artillery batteries, the roads and ditches used for the assault, and the ill-fated march of the 93rd Highlanders across the battlefield.

Chalmette Monument The cornerstone of this shaft honoring the American victory at New Orleans was laid in January 1840, within days after Andrew Jackson visited the field on the 25th anniversary of the battle. The State of Louisiana began construction in 1855, and the monument was completed in 1908.

Malus-Beauregard House Built nearly 20 years after the Battle of New Orleans, the house is named for its first and last owners, Madeleine Pannetier Malus and Judge René Beauregard. Today's restoration reflects the Greek Revival style of a mid-1800s home.

After the Battle Outdoor exhibits near Chalmette Monument, between the Malus-Beauregard House and the river, and along the Battlefield Tour Loop Road tell stories of the land and the people who lived here following the battle, including the development of a thriving free African American community.

Chalmette National Cemetery Drive in from St. Bernard Highway or use the walkway that connects the Battlefield Tour Loop Road to the cemetery (a parking area is located along the Battlefield Tour Loop Road).

Established in May 1864 as a final resting place for Union soldiers who died in Louisiana during the Civil War, the cemetery also contains the remains of veterans of the Spanish-American War, World Wars I and II, and Vietnam. Four Americans who fought in the War of 1812 are buried here, but only one of them fought in the Battle of New Orleans.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to a visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our website.

Regulations Pets are prohibited in Chalmette National Cemetery. • Relic hunting and the possession of metal detectors on park property are forbidden. • Organized games and recreation activities not consistent with the park's historical character are not permitted. • For firearms regulations check the park website.

For Your Safety Watch for and avoid small mounds of dirt. Biting ants may live there.

Source: NPS Brochure (2014)

Documents

2018 Annual Report for Amphibian Monitoring at Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (Jane Carlson, March 28, 2019)

A Study of the Military Topography and Sites Associated with the 1814-15 New Orleans Campaign Draft (Betsy Swanson, June 1985)

A Summary of Biological Inventory Data Collected at Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve: Barataria Preserve, Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/GULN/NRTR-2010/399 (November 2010)

Administrative History of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (Robert S. Blythe, 2012)

Amendment to the General Management Plan, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Louisiana (April 1995)

An Archeological Survey of the Chalmette Battlefield at Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (John E. Cornelison, Jr. and Tammy D. Coooper, 2002)

Archaeological Assessment of the Barataria Unit, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 10 (John Stuart Speaker, Joanna Chase, Carol Poplin, Herschel Franks and R. Christopher Goodwin, December 12, 1986)

Archeological Investigations of Six Spanish Colonial Period Sites: Barataria Unit, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Louisiana Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 25 (Jill-Karen Yakubik, Herschel A. Franks and Marco J. Giardino, 1989)

Archaeological Survey on 65 Acres of Land Adjacent to Bayou Des Familles: Barataria Unit, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Louisiana Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 26 (Herschel A. Franks, Jill-Karen Yakubik and Marco J. Giardino, 1990)

Canal Reclamation at Barataria Preserve Environmental Assessment, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Louisiana (December 2009)

Coastal Hazards & Climate Change Asset Vulnerability Assessment for Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve NPS 467/154051 (K. Peek, B. Tormey, H. Thompson, R. Young, S. Norton, J. McNamee and R. Scavo, March 2017)

Condition Assessment Report: Malus-Beauregard House, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (Joseph K. Oppermann-Architect, 2018)

Cultural Landscape Report: Chalmette Battlefield and Chalmette Cemetery (Kevin Risk, August 1996)

Cultural Landscape Report: Chalmette Unit, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve 95% Draft (WLA Studio, May 2022)

Cultural Landscap Report: Percy-Lobdell Building, Wetlands Acadian Cultural Center, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (WLA Studio, July 2023)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Chalmette Battlefield, Jean Lafitte NHP and Preserve - Chalmette Unit (1998)

Ecological Characterization of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park, Louisiana: Basis for a Management Plan (Nancy C. Taylor, John W. Day, Jr. and George E. Neusaenger, 1988)

Fish and Aquatic Invertebrate Communities in Waterways, and Contaminants in Fish, at the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Louisiana, 1999-2000 USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5065 (Christopher M. Swarzenski, Scott V. Mize, Bruce A. Thompson and Gary W. Peterson, 2004)

Foundation Document, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Louisiana (April 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Louisiana (January 2015)

General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park, Louisiana (July 1982)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2019/2019 (Courtney A. Schupp and Katie KellerLynn, September 2019)

Historic Handbook #29: Chalmette National Historical Park, Louisiana (HTML edition) (J. Fred Roush, 1954)

Historic Land Use Study of a Portion of the Barataria Unit of The Jean Lafitte National Historical Park, Part I (Betsy Swanson, January 15, 1988)

Historic Land Use Study of a Portion of the Barataria Unit of The Jean Lafitte National Historical Park, Part II (Betsy Swanson, January 15, 1988)

Historic Resources Study: The Barataria Unit of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers. No. 5 (Barbara Holmes, 1986)

Historic Resource Study: Chalmette Unit, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (Jerome A. Greene, September 1985)

Historic Structure Report: 417-419 Decatur Street, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (Quinn Evans and VHB, May 2024)

Historic Structure Report: Malus-Beauregard House, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (Joseph K. Oppermann-Architect, April 2021)

Historic Structure Report: Part I & II: The Rene Beauregard House (Francis F. Wilshin, December 31, 1952)

Historic Structure Report: Percy-Lobdell Building, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (WLA Studio, RATIO Architects, Palmer Engineering and Building Conservation Associates, March 2019)

In the Haunts of Jean Lafitte (Frank E. Schoonover, Harper's Monthly Magazine, Vol. 124, December 1911)

Inventory of the Mammals of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve: Barataria Preserve and Chalmette Battlefield Final Report (Craig S. Hood, July 25, 2012)

Junior Rangers — Barataria Preserve, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Legislative History: The Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (1978)

Lower Mississippi Delta Initiative Administrative History (Eppley Institute for Parks & Public Lands, January 2021)

Monitoring Amphibians in Gulf Coast Network Parks, Data Quality Standards NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/GULN/NRR-2018/1745 (Jane E. Carlson and Whitney Granger, September 2018)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Barataria Unit Historic District (Barbara Holmes, July 19, 1988)

Chalmette Unit Historic District (Jerome A. Greene, May 30, 1985)

Natural Areas Significance Study: Mississippi River Delta Region, Louisiana (August 1980)

Natural Resource Summary for Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (JELA) Final Report (Robert J. Cooper, Sandra B. Cedarbaum and Jill J. Gannon, February 2005)

Notes on the Establishment and Development of Chalmette Historical Park (Edward S. Bres, August 1964)

Plant Checklist: Barataria Preserve (July 2006)

Plant Checklist: Chalmette Battlefield (July 2006)

Pore-water and substrate quality of the peat marshes at the Barataria Preserve, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, and comparison with Perchant Basin peat marshes, south Louisiana, 2000-2002 USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2005-5121 (Christopher M. Swarzenski, Thomas W. Doyle and Thomas G. Hargis, 2006)

Preliminary Report On Cannon and Carriages at Chalmette, 1815 (J. Fred Roush, June 1955)

Reptile & Amphibian Monitoring at Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Barataria Preserve: Data Summary, Monitoring Year 2012 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/GULN/NRDS-2013/553 (Robert L. Woodman, September 2013)

Reptile & Amphibian Monitoring at Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Barataria Preserve: Data Summary, Monitoring Year 2013 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/GULN/NRDS-2014/652 (Robert L. Woodman and William Finney, April 2014)

Resource Management Plan, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Draft (December 1, 1997)

Re-survey and Inventory of the Mammals of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve: Barataria Preserve Final Report (Craig S. Hood, June 15, 2006)

Resurvey of quality of surface water and bottom material of the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Louisiana, 1999-2000 USGS Water-Resources Investigations Report 2003-4038 (Christopher M. Swarzenski, 2003)

Special History Study: The Defense of New Orleans 1718-1900 (Jerome A. Greene, February 1982)

Suitability/Feasibility Study, Proposed Jean Lafitte National Cultural Park (1974)

Supplementary Materials for Report on Amphibian Monitoring at Barataria Preserve January 2018-March 2020 Resource Brief (Jane Carlson, Fabiane Spyrer, William Finney and Whitney Granger, June 2020)

Terre Haute de Barataria: An Historic Upland on an Old River Distributary Overtaken by Forest in the Barataria Unit of the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve Monograph XI (©Betsy Swanson, 1991)

The Ecology of Barataria Basin, Louisiana: An Estuarine Profile U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Report 85(7.13) (William H. Conner and John W. Day, Jr., eds., July 1987)

The Road to Recognition, A Study of Louisiana Indians 1880-Present, The Jean Lafitte National Historical Park (Hiram F. Gregory, 1981)

The Search for the Lost Riverfront: Historical and Archeological Investigations at the Chalmette Battlefield, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Parts I, II and II (Ted Birkedal, ed., 2009)

Traditional Use Study: Barataria Preserve, Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve Final Report (Impact Assessment, Inc., August 31, 1998)

Trail Improvements at the Barataria Preserve (August 2023)

Trail Improvements at Barataria Preserve Environmental Assessment (March 2024)

Two-Year Report for Amphibian Monitoring at Barataria Preserve 2018-2020 Resource Brief (Jane Carlson, Fabiane Spyrer, William Finney and Whitney Granger, June 2020)

Vascular Plant Inventories of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, Barataria Preserve and Chalmette Battlefield (Lowell E. Urbatsch, Diane M. Ferguson and Stephanie M. Gunn-Zumo, September 2007 revised 2009)

Water quality of the Barataria Unit; Jean Lafitte National Historical Park, Louisiana USGS Open-File Report 82-691 (Charles R. Garrison, 1982)

"We Know Who We Are": An Ethnographic Overview of the Creole Traditions & Community of Isle Brevelle & Cane River, Louisiana (H.F. Gregory and Joseph Moran, December 1996)

jela/index.htm

Last Updated: 12-Feb-2025