|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER TWELVE:

OPERATION OF MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION CENTER, JANUARY 1943 - NOVEMBER 1945

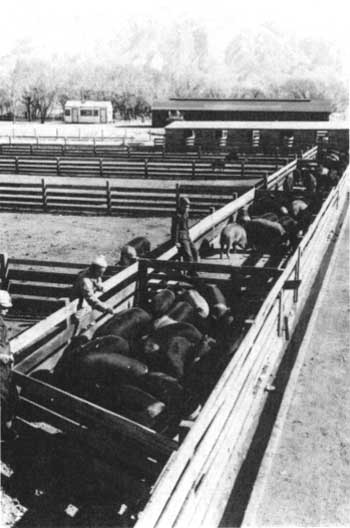

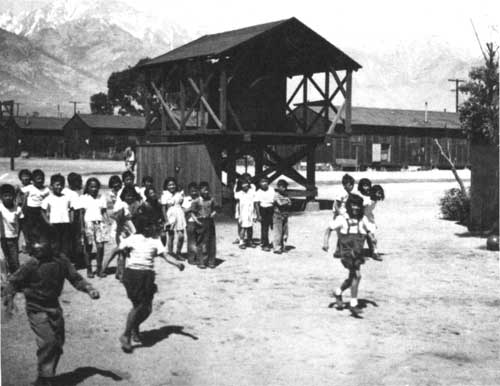

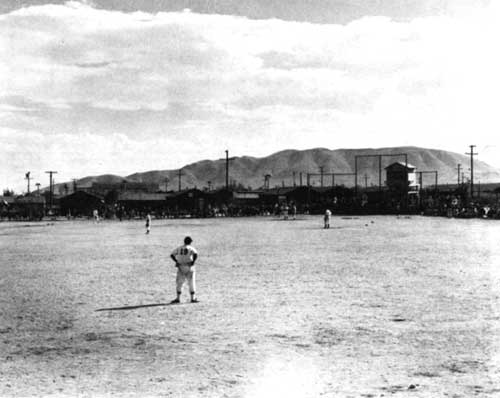

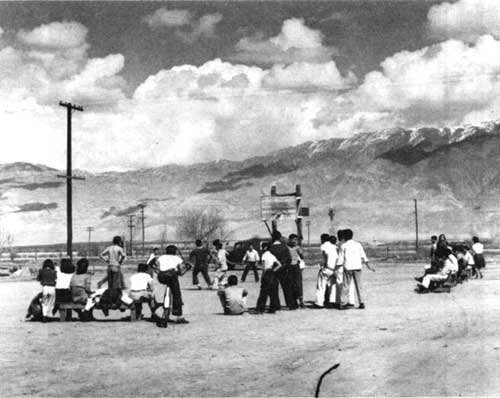

With establishment of the "Peace of Manzanar" following the violence that erupted at the center on December 6, 1942, Project Director Merritt optimistically observed that throughout "1943 and into 1944. . . .the life of the Center crystallized into a pleasant and unexcited mood where normal human relations developed at their best." In spite of the "conflicting emotional decisions that had to be made by Center residents on loyalty, segregation, and relocation," schools "were in full swing," "health services" were "organized to a high state of efficiency," and "industrial operations in the manufacture of clothing, furniture, and many types of food stuffs, occupied and trained many people for later usefulness." Religious "organizations developed strength and large followings." The center agricultural pursuits "began to harvest a crop remarkable in variety and volume for the use of the residents." Recreational and social life "in the American pattern was at high tide and filled with enthusiasm and fine spirit." The "whole community moved outwardly and, in growing degree, inwardly, toward an understanding of the ideals of a high order of simple, peaceful, happy living." This movement was "due, in part, to the fact that the administration secured the cooperation of the evacuees in constructing living quarters on the Center to accommodate all members of the staff." Thus, "every employed staff member was able to live on the Center and work in the spirit of understanding and harmony." It was "due also to the leadership in Town Hall by the Block Managers and their Chairman (Kiyoharu Anzai), and the leadership throughout the Center, by all groups and points of view among the evacuees who found that the tragedy of evacuation and the restrictions of war could be forgotten in the common interest of mutual help in a sound community program.

According to Merritt, Manzanar "reached its highest level of accomplishment" during the autumn of 1944. Stressing the positive attributes of life in the relocation center, he continued:

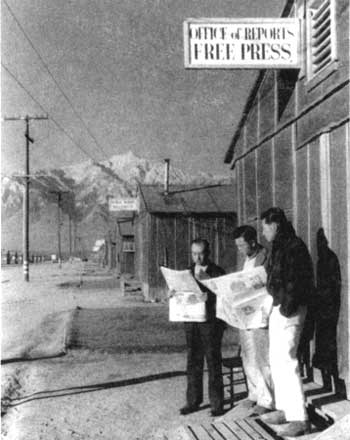

. . . . There was no crime, people were busy and happy, and there was a general understanding and acceptance of the policies of the Washington staff and full cooperation with the Project Director and his staff. The residents of Manzanar were never coddled. Life was severly [sic] simple and as economical as a sixteen-dollar-a-month-wage scale would indicate. Mess hall meals cost an average of 12-1/2 cents; movies and the newspaper were free services from the Co-op; health services without cash gave security to the aged and ill; and the excellent schools prepared children for the eventual return to normal living in America.

On July 12, 1945, WRA Director Myer announced that all relocation centers would be closed by the end of the year, thus initiating the "final phase of feverish relocation activity" at Manzanar. Schools closed on June 1, and week by week other administrative sections in the center completed their responsibilities and closed their doors. The last evacuee left Manzanar on November 21, 1945, and Merritt reported with optimism and pride that the "spirit of the last day was the same as the spirit of the three years previous." The evacuees "were courteous and cooperative," and the staff "remained at its post until the job was complete." [1]

ADMINISTRATIVE ORGANIZATION

On December 15, 1942, shortly after the outbreak of violence at Manzanar, Ralph P. Merritt, who had assumed his position as project director at the camp on November 24, reorganized the entire WRA administrative staff at Manzanar. The streamlined organization, which provided for more efficient operation of the center, consisted of three divisions, each led by an assistant project director, directly supervised by the project director — operations, administrative, and community management. The operations division was placed under the supervision of Robert L. Brown, who had functioned as the center's reports officer, while the administrative division was placed under Edwin H. Hooper, an experienced federal government administrator who had been supervising officer of administration under the old organization. The community management division was placed under the supervision of Lucy W. Adams. Although this organization was not approved at the Washington level until May 13, 1943, it functioned at Manzanar from the date it was established.

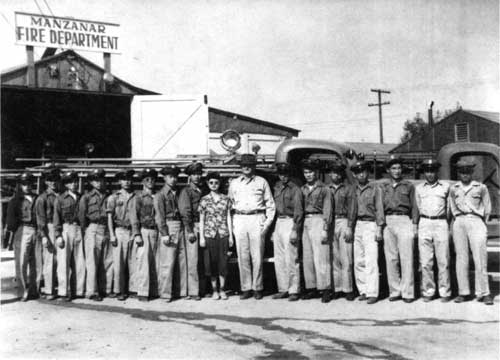

In the new organization, the office of the project director supervised the reports and legal divisions, while the administrative management division was comprised of the supply, finance, office services, personnel records, and statistics sections. The supply section supervised mess management, procurement, and the postal service units. The finance section consisted of the budget and accounts and cost accounting and property control units, the latter unit including warehousing. The statistics section included the former employment and housing division, known as the occupational coding and records section. The balance of the former employment and housing division was placed under the direct supervision of the project director. The community management division supervised the health, education, community enterprise, and welfare sections. The operations division oversaw the internal security agriculture, fire protection, manufacturing, public works, and transportation sections. [2]

As part of the staff reorganization in early 1943, a list of job classifications, definitions, and ratings was prepared by Arthur H. Miller, employment officer at Manzanar, to establish uniformity in job titles for project work for both appointed personnel and evacuee personnel. The U.S. Department of Labor's Dictionary of Occupational Titles was used as a basis for the job titles and descriptions. [3]

Although some minor staff realignments would be implemented periodically, this organizational framework would remain until a final reorganization of the WRA staff at Manzanar on October 1, 1944. Under this new organizational set-up, which would remain in effect until the center closed on November 21, 1945, the office of the project director (Ralph P. Merritt) supervised the legal, reports, and relocation divisions. The administrative management division, under the direction of Assistant Project Director Edwin H. Hooper, supervised the supply, finance, mess operations, statistics, evacuee property, personnel management, and office services sections. The community management division, under the direction of Assistant Project Director Lucy W. Adams, was charged with planning, direction, and coordination of the activities of sections dealing with the total program of the center — internal security, health, education, community activities, welfare, housing, community analysis, community government, and business enterprise sections. When Robert Brown, assistant project director of the operations division, left Manzanar on July 18, 1944, to work for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, Merritt decided that his vacated position would not be filled. Rather, the various sections of the former operations division, consisting of the engineering, motor transport and maintenance, agriculture, and fire protection sections, were parceled out to the administrative and community management divisions for overall direction, while the section chiefs operated somewhat independently. [4] The salary structure for the WRA administrators at Manzanar during late 1944 and 1945 was: Merritt $6,500; assistant project directors and principal medical officer, $5,600; and divisional chiefs and sectional chiefs, $3,800 - $4,600. Several chiefs of smaller sections, such as statistics and office services, were paid $2,000 to $3,200. [5]

Appointed Personnel

During 1943-45, one of the chief problems facing WRA administrators at Manzanar, according to the Final Report, Manzanar, was the "education of the appointed personnel staff and the evacuees in the methods used by the government in its business operations." Most of the appointed staff at Manzanar had never worked for the government before and only a few of the evacuees had. Consequently, both WRA staff members, as well as evacuee employees, repeatedly suggested operational procedures and occasionally conducted policies that violated "either government regulations or law."

At the time of appointment, new WRA employees were provided a considerable amount of information on the purpose, organization, and policies of the WRA. Despite this effort to orient the new employees, however, there was never time to arrange for more than one such conference with each new employee because of inadequate staff personnel.

Recruitment of appointed personnel continued to be a problem throughout the 1943-45 period, since recruitment had to be approved by the 12th Civil Service District which covered the entire Pacific coast from its headquarters in San Francisco. Aside from an acute manpower shortage on the west coast during the war, other factors that contributed to difficulties in recruiting appointed personnel to Manzanar were: (1) high rates of pay, plus overtime and double-time, in west coast war-related industries; (2) isolation of the relocation center; (3) the adverse climate of Owens Valley with its hot dry summers, cold winters, and numerous sand and dust storms; (4) the temporary nature of the employment as many felt that the project would close long before it did; and (5) the fact that a significant portion of the nation's population did not wish to work with persons of Japanese ancestry.

Manzanar was from two to three days by mail service from the San Francisco office of the Civil Service Commission, which made it virtually impossible to obtain approval on an assignment in less than one week. High paying jobs were so plentiful on the west coast that a number of applicants stated that they did not care to wait a week to learn if they were to be approved for employment and accepted other jobs instead. Although the Civil Service Commission offered the project "its wholehearted cooperation,' it was never able to recruit a sufficient number of well-qualified or even reasonably well-qualified applicants interested in working at Manzanar. Thus, the burden of recruitment was left largely to WRA project administrators and personnel. Recruitment was primarily conducted by the assistant project directors through their personal contacts, by the personnel officer through contacts principally in Los Angeles, and by soliciting the cooperation of project staff members who referred to the personnel management section any persons they could interest in employment at the center.

The project staff was credited with securing a high percentage of the 224 persons who were hired after August 1, 1944. Between that date and closure of the project on November 21, 1945, the average number of appointed personnel at Manzanar per month was 155. Some 69 promotions were awarded, almost all of which were for personnel assigned as "War Service Indefinite" employees. The policy of the WRA at Manzanar was to promote wherever possible, thus enhancing the morale of the staff and enabling it to retain the expertise of as many experienced employees as possible.

Inadequate housing initially posed an impediment to employment of appointed personnel. On August 1, 1942, the housing quarters for WRA personnel at Manzanar consisted of nine apartments and 17 bachelor quarters. These units proved insufficient for the growing staff, and in order to obtain as well as retain employees, it became necessary until July 1943 to use evacuee barracks in the camp to house them and their families while additional new quarters were constructed. Beginning that month, as new housing units were completed they were made available to the staff living in the barracks.

By January 1944, all appointed personnel housing units were completed. Families of three or more were assigned to two-bedroom apartments, while families of two received one bedroom apartments. [6] Single women were housed in dormitories, and single men in bachelor quarters, two to an apartment. Single section chiefs or above received one bedroom apartments, as did single employees who secured medical certificates from the principal medical officer showing that they required diets different from those served in the administrative mess, provided that they agreed to share the apartment with another single person.

Lack of recreational facilities also contributed to low WRA employee morale at the isolated relocation center. Until the fall of 1944, there were no staff recreation facilities at the camp. Staff members with automobiles were able to go to nearby towns for limited entertainment, but many staffers had no access to transportation. In late 1944, an Appointed Personnel Recreation Club was organized to provide a clubhouse and recreational facilities for staff members and their families. By Christmas, a clubhouse was ready for occupancy. All employees of the WRA and the post office and their family members over 14 years of age were eligible for membership. Dues were set at one dollar per person per month. The WRA furnished dishes, silverware, chairs, and a refrigerator for the use of the club. A piano, lamp, shuffle board and badminton sets, electric and coffee grills, and card tables were purchased by club members at a cost of approximately $150. The clubhouse featured a snack bar that served coffee, hamburgers, and other snacks. The club was organized into sections of special interest, such as music, bridge, and sports. Special occasions were observed with picnics, parties, or dances. Surplus funds from the club were to be presented to Hillcrest Sanitarium for use by evacuees when discharged from the hospital.

The staff at Manzanar averaged slightly less than 200 during the entire operation of the center. Between May 1 and December 1942, 209 new employees were hired by the WRA and 20 additional personnel were transferred from other government agencies to the camp, thus providing the center with an average staff of slightly over 200 persons for that period. In 1943, 234 new appointments were made, and nine employees were transferred from other government agencies. The following year, 86 new appointments and six transferees were added to the staff. In 1945, 223 new appointments and 11 transferees were made. From May 1,1942, to December 31, 1945, 788 personnel were hired or transferred to maintain an average center staff of slightly less than 200. [7]

At the request of Project Director Merritt, Arch W. Davis, who had become reports officer at Manzanar in September 1944, initiated the Manzanar Magpie, a small mimeographed paper designed to boost staff morale and increase communication among appointed personnel. The paper, which was printed on a monthly basis from November 20, 1944, to April 1945, carried information of interest to appointed personnel, as well as amusing articles concerning employees and poems, rhymes, and other articles composed by personnel. [8]

Evacuee Personnel

During 1943-45, evacuee personnel constituted the majority of the work force at Manzanar. Throughout these years, they continued to be paid $12, $16, and $19 per month, depending on skills classification of their work. Employment procedures that were developed during 1942 became more formalized, and on-the-job training programs and efforts to provide for a more disciplined and efficient work force were implemented.

As of February 28, 1943, a total of 4,789 evacuees were employed at Manzanar. This number included:

Project administration 119 Mess operations 1,638 Warehousing 178 Transportation Operations 87 Health and sanitation 386 Education 211 Internal Security 66 Housing 86 Other Community Services 435 Building Construction 224 Buildings and Grounds Maintenance 655 Fire Protection 46 Land Clearing 140 Employment 59 Agriculture 131 Industry 127 Community Enterprises 201

Of this total, 146 males and 19 females were making $12; 2,989 males and 1,186 females were making $16; and 355 males and 94 females were making $19. [9]

As the relocation of evacuees out of Manzanar accelerated during early 1943, evacuee transfers from one job to another became frequent, thus causing instability in the center's workforce. To correct this problem, the administration took steps to "freeze" many of the employees in their jobs. This freeze, however, was subject to many qualifications as indicated in a memorandum on May 20, 1943:

No worker may transfer from a more essential job to a less essential job, but he may transfer from the less essential job to a more essential one. Transfers may be made between less essential jobs, provided the transferee is not qualified for a more essential job vacancy Thus far, the Employment Office has been able to meet practically all the requirements of the various departments so that no work has really suffered through the shrinkage of population, but this is rapidly becoming more difficult.

Department heads and section heads are encouraged to come to the Employment Office for a frank discussion of any work problems so that every effort may be made to make the necessary adjustments, particularly in key jobs, in order to keep all the work rolling.

The Project Director has designated the following jobs as more essential because they concern the care of the sick, internal security, fire protection, the feeding of the people, the payment of allowances, the planting and harvesting of crops, and the maintenance of utility services:

Hospital professional and technical workers, orderlies, and nurses' aides

Internal Security policemen

Fire Department firemen

Finance Department bookkeepers, clerks, accountants, and typists

Mess Division cooks and workers in food warehouses and storage, food transportation

Agriculture farm workers for planting and harvesting crops Public Works workers necessary for the maintenance and upkeep of utility services and care of government property

Although the WRA relocation program resulted in a declining population at Manzanar during 1943 and 1944, approximately 42 to 51 percent of the employable evacuee population in the camp continued to be employed during those years. Of the 9,170 residents in April 1943, 4,267 or 46.5 percent were employed. By December 1944, 2,448 of the 5,549 remaining residents (44.1 percent) were employed. In March 1945, increasing relocation resulted in a "sporadic job termination movement," and a sharp decline in evacuee personnel began to have a significant impact on center operations during subsequent months, resulting in WRA efforts to recruit every available evacuee still in the center. [10]

CENTER PHOTOGRAPHY

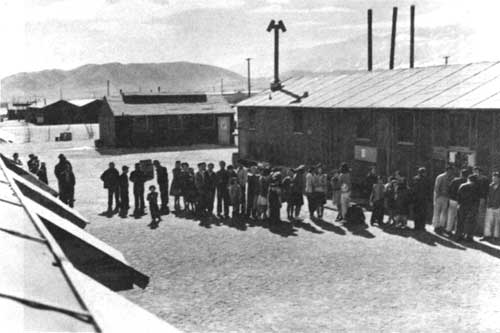

Although the WRA had not formalized a policy governing the photographing of its relocation program, three of its official agency photographers visited Manzanar to take photos of its operations during 1942. Clem Albers visited in the camp in early April, just after the first large groups of evacuees began arriving and almost two months before the WRA took over administration of the camp from the WCCA. Francis Stewart visited the center in late May and early June 1942 and was at the site when the WRA took over administration of the camp on June 1. Later in February 1943, he would return to the center to take more photographs. In late June-early July 1942, Dorothea Lange traveled to the center to take photos. Selected photographs taken by Albers, Stewart, and Lange were published in Stone S. Ishimaru, War Relocation Authority, Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California: 1942-1945 (Los Angeles, TecCom Productions, 1987). The entire collection of their photographs may be found in Record Group 210 of the Still Picture Branch at Archives II of the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland. [11]

Of the three official photographers, Lange was the most noted, having achieved professional recognition for her documentation of migrant labor conditions during the Depression while working for the Farm Security Administration. Because of her reputation as a social activist with liberal political leanings, her WRA photographs were scrutinized closely by military authorities and many were impounded. Working from an "antagonist" position, Lange took photographs that were intended to reveal the injustice of evacuation and relocation. In April 1942 she began her WRA work in northern California by photographing the "normal life" of Japanese American families who had been in America for several generations, emphasizing their contributions to American society. Lange wanted her photographs to reveal the "pattern of mass blame" and its physical, psychological, and social effects on the evacuees during evacuation, as well as the process of transforming the assembly and relocation centers from spartan barracks into livable dwellings. From Lange's perspective, the environment of Manzanar, with its climatic challenges posed by heat, dust, and extreme cold, epitomized the oppression of its residents. Although few of her photographs were published during the war because they were seen as advocating an "unacceptable view" of evacuation and relocation, they were reinterpreted during the late 1960s and 1970s as providing a "true" picture of those events. In 1972, for instance, many of her photos were selected by Maisie and Richard Conrat for an exhibit and book of pictures, entitled Executive Order 9066: The Internment of 110,000 Japanese Americans (Los Angeles, California Historical Society, 1972). The traveling exhibit was presented, under the joint sponsorship of the National Archives, the California Historical Society, and the Japanese American Citizens League, at the Whitney Museum in New York, the Corcoran in Washington, the De Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco, and a Tokyo department store. [12]

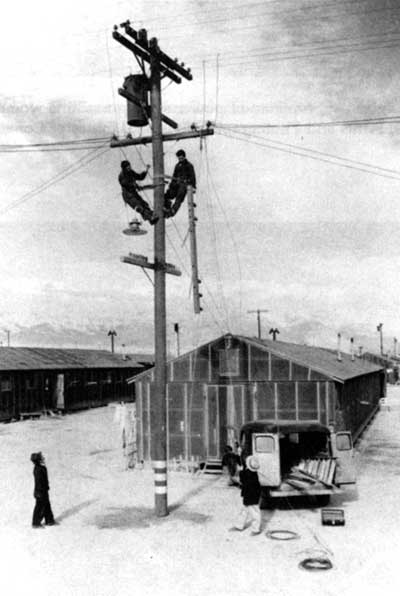

Although Albers, Stewart, and Lange visited Manzanar during 1942 to take photographs, it was not until January 2, 1943, that the WRA issued Administrative Instruction No. 74, describing regulations and procedures for photography in the relocation centers. The instruction provided that it was "the intention of the War Relocation Authority to document its program as fully as possible by means of photographs." The "major part of such documentation" would be "in black and white still photographs," but to "a lesser extent photographic documentation " would also "include color stills and movies." Photographs would be used "not only for documentary purposes, but also for information to be made available to the public and to the evacuees." Responsibility for the agency's photographic documentation program was assigned to the photographic section in Denver, Colorado, an office responsible to the chief of the reports division in the Washington office.

According to the instruction, WRA photographers would visit all relocation centers and will make photographic records of activities, "giving approximately equal attention to all" elements of the centers' operations. WRA photographers would "at all times observe the right of privacy of the individual." They would take photos of "industries within relocation centers making goods and articles for the armed forces, as a necessary part of documentation." However, such pictures would not be used for any "purpose other than documentation without approval of appropriate officials of the Army or Navy." WRA photographers were forbidden to take photographs "of personnel, equipment, or installations of military forces at relocation centers, unless special permission to do so is secured from appropriate officials of the Army."

Although the WRA placed "no restriction or prohibition on possession or use of cameras in relocation areas," it would observe "restrictions and prohibitions of other agencies of the government, such as the War Department and Department of Justice." Under regulations of the Western Defense Command, cameras were regarded as contraband for persons of Japanese ancestry within the areas of that command. Thus, photographs could "be taken in those centers only by official photographers of WRA, or by persons, not excluded by the applicable regulations, who are granted special permits by the Project Director or by the Director of WRA." Department of Justice regulations prohibited the possession or use of cameras by Japanese nationals anywhere in the United States.

Under the terms of the WRA instruction, evacuee-established cooperative associations in the relocation centers could establish photographic services. If such a service was established, however, "the prohibition against the use of cameras by alien evacuees, which is applicable to all relocation centers, or by any evacuee where the relocation center [such as Manzanar] is within the Western Defense Command, must be observed."

The reports officer in each relocation center would be provided with a camera "for taking photographs, with the objective of enabling him to photograph significant events and activities at the center when no official photographer is present, and also to render certain limited photographic service to the evacuees," such as family photographs at funerals.

Film of all official WRA photographs were to be sent undeveloped to the photographic section's laboratory in Denver. One file print of each exposure was to be sent to the chief of the division in Washington for clearance. Photographs not suitable for publication, because of subject matter, would be "designated for impounding, and negatives of such photographs" would "be forwarded to Washington." "All existing prints of such photographs" would "be destroyed." If approved, one file print would be made by the photo laboratory for its use, and one print would be sent to the relocation center in which it was taken. Photos would be released for publication by the reports officer at each center or by the chief of the reports division in Washington. [13]

During the fall of 1943, Ansel Adams, recognized as one of the finest landscape photographers and most exacting printers in the history of American photography, was requested by Project Director Merritt to travel to Manzanar to "interpret the situation as it had developed in time." Adams had wanted to contribute to the war effort, but he was too old for military service. Thus, he welcomed the opportunity to photographically document the relocation center. He had been upset by the disruptive effect the evacuation and relocation program was having on the lives of evacuee friends, but he "would not say the operation as a whole was unjustified." He noted that "the fact remains that we, as a nation, were in the most potentially precarious moment or our history — stunned, seriously hurt, unorganized for actual war." Adams did not consider the evacuation as a threat to democratic principles, he saw Manzanar as "only a wartime detour on the road of American citizenship, . . . a symbol of the whole pattern of relocation — a vast expression of a government working to find suitable haven for its war-dislocated minorities." Thus, he took some 200 photographs (at present the photographs are in the Ansel Adams Collection in the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress, although copies of some are also in the aforementioned Record Group 210) that would be organized in exhibit form by the Department of Photography of the Museum of Modern Art in New York in November 1944 and published in a book entitled Born Free and Equal (New York, U.S. Camera, 1944). The subtitle of the book, "Photographs of the Loyal Japanese Americans at Manzanar Relocation Center," emphasized his efforts "to record the influence of the tremendous landscape of Inyo on the life and spirit of thousands of people living by force of circumstance in the Relocation Center of Manzanar," While the "people and their activities" were his "chief concern," there was "much emphasis on the land" and the influence of the camp's natural environment throughout this book. Adams stated in the foreword:

This book in no way attempts a sociological analysis of the people and their problem. It is addressed to the average American citizen, and is conceived on a human, emotional basis, accenting the realities of the individual and his environment rather than considering the loyal Japanese-Americans as an abstract, amorphous, minority group. This impersonal grouping, while essential to the factual study of racial and sociological problems, frequently submerges the individual, who is of greatest importance. . . .

Adams wanted "the reader to feel he has been with me in Manzanar, has met some of the people, and has known the mood of the Center and its environment — thereby drawing his own conclusions — rather than impose upon him any doctrine or advocate any sociological action." He claimed that he "intentionally avoided the sponsorship of governmental or civil organizations, not because I have doubts of their sincerity and effectiveness, but because I wish to make this work a strictly personal concept and expression." Adams hoped that the "content and message of this book will suggest that the broad concepts of American citizenship, and of liberal, democratic life the world over, must be protected in the prosecution of the war, and sustained in the building of the peace to come." As an apologist for the evacuation, he thus used his photos to demonstrate the success of the evacuation and relocation program and to emphasize the successful adaptation of the evacuees to life in the camp. He hoped his photographs, including close portraits of evacuees, small business, industrial, and agricultural activities, family groupings, and social activities, would reassure Americans outside the camp that the people of Manzanar were now worthy of equal status, and could make valuable contributions to any American community. [14]

The best source of photographs for documentation of Manzanar is the Toyo Miyatake Collection. Miyatake, a 47-year-old photographer who had operated a photograph studio in Los Angeles since the 1920s, was evacuated, along with his family, to Manzanar in 1942. As a professional photographer, it was perhaps more his instinct than any historical motive that initially made him smuggle his lens and film holder into the camp along with the few personal belongings that he and his family were allowed to take. Although prohibited to take photos, Miyatake collected pieces of wood and various plumbing fixtures, and with the help of a carpenter friend, he secretly built a crude wooden box camera. Attached to the back was his one 4-inch x 5 -inch sheet film holder, while his lens, fitted to the front, was focused by rotating it on the end of a threaded drain pipe. Superficially, the camera looked like a lunch pail, enabling his clandestine photographic documentation to continue. Ordering film by mail from his supplier in Los Angeles, Miyatake began what he called his "historic duty." After some nine months, he was caught by the camp police in early 1943 and obliged to explain his conduct to Project Director Ralph P. Merritt. Notwithstanding Miyatake's violation of military regulations, the director concurred with the evacuee's explanation that his photographs represented a history he was compelled to record — his own. As a concession to the military rule forbidding Japanese Americans the right to take photographs, Merritt allowed Miyatake to set up pictures of his choice, but a Caucasian appointed staff member would trip the shutter. As camp life "normalized" in early 1943, this restriction was relaxed and Miyatake was allowed to send to Los Angeles for his studio and darkroom equipment. Later that year, he establish a fully equipped photo studio at Manzanar that was operated by Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises. Thus, he became the unofficially appointed camp photographer. Miyatake was also permitted to travel to the Poston and Gila River relocation centers to take photos, some of which were published in Allen H. Eaton's Beauty Behind Barbed Wire (New York, Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1952). Selected photographs from the Miyatake Collection were published in Graham Howe, Patrick Nagatani, and Scott Rankin, eds., Two Views of Manzanar: An Exhibition of Photographs by Ansel Adams, Toyo Miyatake (Los Angeles, Regents of the University of California, 1978) and in Atsufumi Miyatake, Taisuke Fujishima and Eikoh Hosee, eds., Toyo Miyatake Behind the Camera; 1923-1979, trans. by Paul Petite (Tokyo, Bungeishunju Co., Ltd., 1984). Miyatake's collection of more than 1,000 photographs of Manzanar (presently housed at the Toyo Miyatake Studio operated by his son, Archie Miyatake, in San Gabriel, California) depict the growth and quality of life in his community, showing agricultural growth, artistic involvement, professional acumen, and typical life scenes during the 1943-45 period. [15]

COMMUNITY GOVERNMENT

Reestablishment

On New Year's Day, 1943, Merritt sent a letter to WRA Director Dillon Myer, the substance of which became the charter on which community government would be reestablished in the center and upon which the "Peace of Manzanar" would ultimately rest. In the letter, Merritt stated that every effort had been exhausted to bring about the type of center government desired by Washington. However, he rejected the form of self-government as proposed by the Washington office:

Viewing the plan for creation of evacuee self-government, as an analyst and not as a critic, it now seems clear that the positions of the majority of the evacuees toward self-government deserves serious open-minded consideration by the Authority. Evacuees who approach the plan of self government without emotion and with the desire to be constructive divide themselves roughly into two classes: first, those who question the sincerity of a plan of self-government which prohibits a large percentage (and particularly the more mature people) from the holding of office and, secondly, the exercise of any plan of self-government prepared and limited by the authorities above, whose authority includes the maintenance of a barbed-wire fence as visual evidence of the actual complete lack of the fundamentals of self-government. Their view boils down to the conclusion that it is silly for mature men to spend time playing with dolls.

It was Merritt's belief that any form of government which was democratic and American in spirit must of necessity represent the will of the people. Democratic government could not be handed down to people by higher authority, but must be based on understanding acceptance of a charter representing the will of the governed.

Merritt continued:

The conclusions reached, after long discussion and thoughtful consideration of the Japanese leadership at Manzanar, appears to be that the majority of the evacuees will immediately accept a form of government comprising judicial committees, internal policing, the administration of blocks, and advisory action on the great range of problems touching the lives of all evacuees, provided the Project Director assumes the responsibility for proposing an acceptable form of government and supervises its general administration. Definite and overwhelming opposition has been growing and now must be accepted against attempting to involve the evacuees in responsibility for a type of apparent self-government purporting to originate from within their body, yet in fact designed to implicate them in a participation and acceptance of the fundamentals of evacuation, detention and control, and in the artificialities of a wartime experiment, by which citizens and Japanese Nationals are deprived of liberties accorded other citizens and other alien Nationals.

Opposition to the establishment of evacuee government as set forth in the purposed [sic] charter has come from all elements in the camp. The Issei believe that deprivation of their holding of office further accentuates discrimination. An active Kibei group is pro-Japanese in tendency and unwilling to participate in any form of American governmental procedure. Many of the Nisei base all their opposition on the fallacy of the offer of the opportunities of self-government which is to exist in form only.

The discussion to this point has had to do with the adoption or rejection of the proposed charter. All this, however, does not mean that there is no opportunity for the growth and development of phases of self-government based upon a slowly developing degree of confidence between the evacuees and the administration, and a clear recognition of the part of the evacuees for the need of certain forms of internal government operation. . . .

I am not discouraged on the development of sound and sincere principals [sic] of self-government at Manzanar, based upon the demonstration of need for the functions of government and the expressed desire of the evacuees to participate, in their own interests, and in suitable compliance with the policies of the Authority. I do not believe that any tailor-made program for self-government, operating on a time schedule, could be effective, acceptable, or even a reality. Self-government is a method of group procedure that arises from recognized needs and is developed from within, with the acceptance of the majority, to meet such needs. That such method of procedure must also be acceptable to the Authority is obvious. Self-governing is a process of growth from within, not the imposition of authority from without. It is a slow process based on bitter experience. Therefore, temporary measures, not labeled self-government, must be used as a bridge to the desired point. [16]

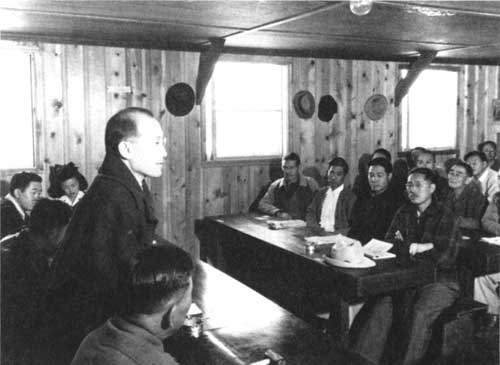

On January 6, 1943, one month after violence erupted in the camp, the block managers reconvened and began weekly meetings with Merritt "for a complete, full, and candid discussion of all matters which touched the administration of the Center." Gradually, "confidence between the Administration and the evacuees developed and an unwritten code of procedure and regulations was created through mutual understanding." [17]

Peace Committee

In addition to cooperation and consultation with the block managers, Merritt consolidated his policy of accommodation at Manzanar in early 1943 by acknowledging and working with a "Peace Committee," a spontaneous arbitration and control group of evacuees that emerged at Manzanar in the wake of the violence. Consisting of representatives from each block, the committee was led by Seigoro Murakami, who had been a judo instructor and Japanese language school teacher before evacuation and had organized a judo instruction program in the camp. [18]

Designations of "Mayor of Manzanar" and "Father of Manzanar"

In March 1943, Kiyoharu Anzai, an Issei who had studied at the University of California and the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley prior to evacuation and was the father of a Nisei military volunteer, became chairman of the block managers. Merritt, conscious of Japanese cultural patterns, deferred to those traditions by conferring the honorary title, "Mayor of Manzanar," on Anzai, who would remain as chairman of the block managers and discharge the duties of his honorary position until the close of the center in 1945.

After becoming chairman of the block managers and receiving his honorary title, Anzai, working together with Merritt, "found a way to bring the Administration and the evacuees into a more cordial relationship." Using "the accepted Japanese cultural approach," Anzai reciprocated Merritt's overtures of goodwill by designating the project director as the "Father of Manzanar." Realizing the delicacy "of the compliment and the possibilities of accord arising from the use of this title," Merritt "permitted and joined in the device by which it was possible for Japanese aliens to give complete loyalty to Caucasian leadership." The "device" was used by Merritt to encourage the alien evacuees who dominated the block managers assembly "to advocate the American way of living as a means of creating better public acceptance for their children."

"Peace of Manzanar"

Shortly thereafter, an alien, who had previously criticized the government and whose attitude had been described as pro-Japanese, became the "chief advocate of the school system," while another Issei "constituted himself as the public relations officer of the Project hospital." In response, Merritt proposed that "the common ground of agreement should be the 'Peace of Manzanar' which should be preserved at all costs by all persons." This theme, according to the Final Report, Manzanar, would form the framework for "all evacuee activities from January 1943 until the date of the closing of the Center." Regardless "of differences in nationalistic views, of the selfish interests of organizations or individuals, the 'Peace of Manzanar' was maintained and the result was community accord, peace and cooperation."

Block managers were elected "by the formal or informal vote of the residents of their blocks subject to veto" by Merritt. The project director only exercised the veto on two occasions, but in both instances the majority of the block managers agreed that the person "was unsuitable for the position."

The block managers assembly became "a vital and important force within the life of the Center." Its secretary had a staff who arranged for all evacuee meetings, assigned rooms for such meetings, and directed the "life of the Center in acceptable channels." According to the Final Report, Manzanar, few "important events took place in Manzanar without the support or approval of Town Hall, the little building from which the forces of the peaceful life of Manzanar flowed."

Thus, community government at Manzanar during 1943-45 "was not cut to the formal pattern followed in other centers." Instead, "it arose," according to the Final Report, Manzanar, "from the people and accomplished the purposes of the Authority by creating peace, good-will and renewed confidence in the American way of living." [19]

EDUCATION

Recommencement of School

Following the violence on Sunday, December 6, 1942, WRA education administrators attempted to hold school as usual the next day. Because of continuing unrest and disruptions, however, "it was considered unwise for the children to congregate in groups." The administrators then determined that the schools could not be reopened successfully until requested by the evacuees. In response, the Peace Committee sponsored a resolution, which was circulated in every block and signed by virtually all parents of school-aged children:

As parents of school-aged children in Manzanar we wish to endorse the present Manzanar school program. We will see that our children attend regularly and behave in an orderly, polite manner at school and toward the teachers. We wish to cooperate with the school department in carrying out the best possible education program in a peaceful, orderly fashion. We trust that the schools can reopen soon after the first of the year.

School authorities meanwhile took advantage of the "recess" to complete improvements in the classrooms and formalize school policies and procedures. Merritt established "lines of procedure" that "released materials and labor for work on the school barracks" and "facilitated the distribution of books, supplies, and other equipment."

The interim "recess" also provided time in which to improve "the organization and morale of the teaching staff." After the violence, teachers volunteered "to help carry on emergency services" in the center. Nine teachers resigned in December, but "for those who remained improved relations with other appointed personnel became evident." As the camp returned to normal, teachers' study groups formed to revise and improve curricula and plan a schoolwide testing program. Three new teachers arrived in addition to a nursery-school supervisor who established a preschool teachers training program. The nursery, elementary, secondary school, and adult education units, as well as the libraries and the visual aids museum, were reorganized to make them more "autonomous."

On January 6, 1943, the education office issued an announcement that elementary, secondary school, and adult education classes would be resumed on Monday, January 11. A new regulation, stating that no one over 16 years of age would be required to attend school, was implemented, thus providing for "smoother high-school functioning thereafter." Some 25 former pupils over 16 years of age withdrew from school. The bulletin announcing commencement of the school program stated:

The re-opening of school brings additional responsibility to students and parents. Teachers and administrators are determined that schools shall offer the same type of work and meet the standards of the public schools of California. Most students desire to do serious work, and they recognize the importance of an adequate education for successful living. Disturbances and misconduct will be dealt with firmly. Expelling from school and other disciplinary measures will be taken as necessary. Earnest and sincere students will be protected from such disturbances.

Although elementary and adult classes reopened on January 11, a shortage of material delayed construction in the secondary school block. Thus, high school classes did not reopen until January 18. Two weeks later on February 1, nursery school classes also resumed.

Students returning to school found "plasterboard lining their ceilings and walls, and linoleum on their floors." Stoves had been installed, so that the rooms were warm and fairly comfortable for the first time since cold weather had set in during the fall of 1942. The schoolrooms had "chairs for all the children, with tables for most, as well as supply cabinets, bookcases, blackboards, and shelves." The teachers attempted "to smooth over the break that had been caused by the riot and to turn their energies to educating the children." The Parent-Teachers Association conducted a series of back-to-school meetings which were attended by more than 2,000 parents and adults. [20]

School Standards

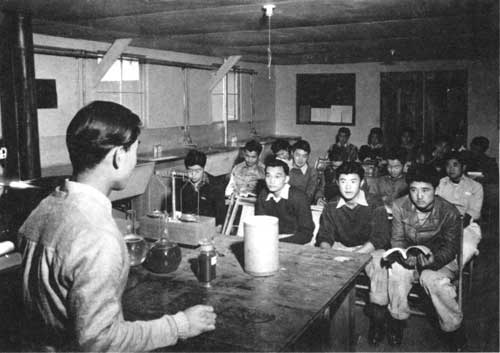

By the spring of 1943, the schools at Manzanar had become "fairly well organized."

On June 7-8, 1943, the chief of the Division of Secondary Education in the State Department of Education visited Manzanar to inspect the junior-senior high school program. On June 21, Walter F. Dexter, State Superintendent of Public Instruction, informed WRA Director Myer that the "junior-senior high school at Manzanar meets the standards contained in the School Code of California and the Rules and Regulations of the California State Board of Education." The teachers "hold appropriate California credentials with but few exceptions and in these instances the teachers are well trained." The "course of study has been carefully developed, appropriate school facilities and equipment have been provided, and instruction is well organized." [21]

The elementary school was examined by the Helen Heffernan, Chief, Division of Elementary Education of the State Department of Education on September 23-24, 1943, and on October 11 she wrote to Carter:

On the basis of the observation, may I take this opportunity to state that 1 believe the quality of education which I observed in the schools at Manzanar compares favorably with the educational program in the schools from which these children came.

It was particularly interesting to me to observe the development of your nursery school and kindergarten program. For children from homes in which a foreign language is frequently the spoken language, this early opportunity for contact with English-speaking people is of the utmost importance. Under the conditions which exist in the relocation settlement it is of tremendous value that young children of preschool age have the opportunities you provide for them for use of educative materials, undisturbed rest, and excellent guidance on the part of young women who were charged with this responsibility. The nursery school and kindergarten programs provide opportunity beyond that available to many children in the school districts from which the Manzanar school children were transferred.

It is a pleasure to comment specifically upon the excellent physical education and health education in progress. The individual records being kept for each child are the equivalent of those kept in efficient school systems.

It was a source of much satisfaction to me to examine the records on standardized tests which have been given at Manzanar during the past year, and to note that the children enrolled in your schools have reached or surpassed the national norms on such tests. In view of the dislocation they experienced in their educational program last year, the standards which they have attained is the best possible evidence of the effectiveness of your educational program and the devotion with which teachers have worked with these children. [22]

In addition to these evaluations, the Committee on School Relations from the University of California, Berkeley, the accrediting agency of the state, inspected the secondary school program and placed Manzanar High School on its accredited list. Thus, the University of California was willing to accept Manzanar high school graduates, although evacuees were prohibited from Military Areas Nos. 1 and 2. [23]

As they sought to provide a quality education to the evacuees at Manzanar during the 1943-45 period, the educators at Manzanar began "to reach several common agreements as to certain beliefs which were shaping our education program." These key tenets, according to superintendent Carter, included:

Japanese American citizens must be taught the same fundamental skills as any other American citizens, and special emphasis should be given to English and speech instruction.

There must be a conscious effort on the part of the classroom teacher to promote a better understanding of American ideals and loyalty to American institutions.

The schools must equip the child with better than average formal educational and vocational experience.

The teacher must provide the link "between the stagnant life with the center and the changing world beyond the barbed wire fence."

The teacher must not allow the Japanese American child to become too absorbed in his misfortunes and feelings of being the only object of prejudice in America.

Teachers in adult education programs must recognize that even greater skill must be "exercised in bringing American culture to the Issei and Kibei." [24]

Buildings/Facilities

According to the Final Report, Manzanar, "great ingenuity was required in setting up special rooms for the high-school classes." A high school study hall-library was "built in the large mess hall building" of Block 7. The kitchen-pantry section of the mess hall was developed into a two-room home economics unit. A model home apartment was set up in the high school block. This project was described in a mimeographed bulletin, entitled "A Barrack Becomes A Home," prepared by the Manzanar home economics supervisor. In the bulletin, the importance of the model home was explained:

It has been felt by many authorities that this lack of a normal home situation has had a more detrimental influence on the young people of the camp than any other phase of the evacuation. Under such circumstances, the need for training in all fields of home economics was far greater than in the average school. . . .

The high school clothing classes were taught in two ironing rooms in Block 7. Thus, they were equipped with electric outlets for irons and electric machines.

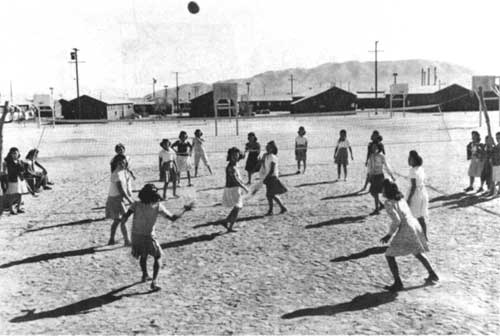

Prior to completion of the Auditorium during the late spring of 1944, physical education facilities were "inadequate." Nevertheless, the facilities, as described in a mimeographed bulletin, entitled "Health and Physical Education," prepared by the health and physical education supervisor, included a hazard course, health room, and outdoor play equipment.

The physics and chemistry laboratory was placed in a laundry building. The boiler room was converted into a storage and supply room, while every other laundry tub in the laundry room was covered by a work board, with a supply cabinet set in between each tub. Large work tables were spaced in the center of the room.

During the 1943-44 school year, classrooms were enlarged, with each barrack divided into three classrooms. Each classroom had sufficient arm chairs or students' tables to "give adequate service."

One barrack was set aside for music and "little-theater work." After the Auditorium, was completed, the "little-theater building" proved "more desirable for class work."

The education superintendent's, business, and high school offices were located in one barrack "well finished inside, with adequate office equipment." The elementary school office was located with the elementary school in Block 16, while the adult education office was in Block 7 near the library office, the visual aids room, and the cosmetology school. [25]

Preschool Program

The preschool program operated under the supervision of the Superintendent of Education until early 1943, when a trained nursery school worker arrived at Manzanar. After the nursery schools were well organized, the supervisor was made responsible for the kindergarten program. Thereafter, the preschool program was administered under the principal of the elementary school.

During 1942-43, Manzanar authorities organized 18 nursery school units and seven kindergartens. Of the nursery school units, six were afternoon sleep sessions. The preschool units were housed in "regular elementary-school buildings scattered throughout the community." An undated map in the "Education Section" of the Final Report, Manzanar shows that nursery schools were located in Blocks 1, 9, 11,17, 20, 23, 30, and 32, while kindergartens were located in Blocks 1, 11, 20, and 31. Almost 1,000 children between the ages of three and six participated "in an environment which emphasized health, safety social and emotional adjustment, and mental development through wisely selected play materials."

Continuous "in-service training of evacuee teachers through field supervision, demonstration, and staff meetings was offered as a requirement since no credentialed teachers trained in preschool techniques and methods were available." More than one-half of the preschool teaching; staff were young English-speaking mothers of nursery-school children. Training courses covered subjects such as child development, techniques and methods, music, rhythm, arts, handicrafts, play materials, play yard equipment, child records, and administrative reports.

The parents of all children enrolled in the preschool automatically became members of a parent club that functioned in connection with a nursery or kindergarten unit. A central board, consisting of the chairmen of the individual unite, the preschool parent-coordinator, preschool supervisor, and president of the board selected at large, coordinated all phases of the preschool parent activities. All parents held membership in the national Parent-Teachers Association.

Parents shared in financing the preschool program and contributed "many hours of service" in constructing, maintaining, and beautifying the preschool rooms and equipment. A bazaar and quilting bee netted funds sufficient to finance equipment needs for more than two years. A monthly fee of 10 cents per parent enabled the children to have periodic parties.

Because of the relocation of most of their evacuee teachers during 1944-45, the preschools "were streamlined almost out of existence." Two of these teachers went to college to major in preschool education, and a number of others began to teach in nursery schools and child care centers outside of California. Despite the decline of the preschool program, however, all children of kindergarten age completed their kindergarten year. The success of the preschool program at Manzanar was shown in the children's ability to meet first-grade school requirements. In 1942, 25 percent of the children entering the first grade were unable to speak English. The children of the classes of 1943 and 1944, on the other hand, had attended preschool, and all of these children, except for one child who had been transferred from Tule Lake, were able to speak English when entering the first grade. [26]

Elementary School Program

The elementary school program was difficult to administer until the 1944-45 school year, when the various grades (kindergarten — sixth grade) were consolidated in Block 16. During the first two school terms, it was necessary to scatter classrooms throughout 12 different blocks — Block 1, Building 14; Block 3, Building 15; Block 5, Building 15; Block 9, Building 15; Block II, Building 15; Block 17, Building 15; Block 20, Building 15; Block 21, Building 15; Block 23, Building 15; Block 30, Building 15; Block 31, Building 15; and Block 32, Building 15. [27]

During 1943-44, the Manzanar elementary school was directed by Principal Clyde L. Simpson, "whose enthusiastic leadership put the elementary schools on a standard California public school basis." When Simpson was transferred to the relocation section in January 1945, Eldredge Dykes, the head high school teacher and an experienced school administrator, assumed his position.

The elementary school staff reached its greatest number during the spring of 1943, when it had 35 teachers and a supervisor of teacher-training, principal, vice-principal, and music supervisor. On May 29, 1945, when the Manzanar schools closed, the elementary staff included 17 teachers and a principal.

Standardized achievement tests were administered to all elementary children each year. A large percentage of the children had Nisei parents, which gave them "a better advantage in English performance." The scores of the elementary children, at each testing, "reached or exceed the national norms on all the skill subjects." They were especially "high in spelling and arithmetic computation." According to the Final Report, Manzanar, the center's elementary school curriculum "was like that of any other progressive California school which emphasizes the social studies program." The report further stated that the " school newspaper, the softball league games, the assembly programs, the girls' glee club, the rhythm bands, flute bands, and well-organized playground work all indicated matured activities that are not usually found in a three-year-old school." [28]

Secondary School Program

Leon C. High served as the secondary school principal during the 1942-43 school term. After leaving the center to accept employment as a school principal in a nearby town, Rollin C. Fox served as principal during 1943-45, completing "the organization of the high-school program," which was similar to that "found in any public school." The secondary school took over all of the barracks in Block 7. In addition, some classes were conducted in Block I, Building 8, Block 1, Building 15, and the ironing room in Block 7. [29]

In general intelligence, Manzanar's secondary students "stood at about the same level" as "students in the public schools throughout the nation" despite "a reading and language handicap." In age, Manzanar's secondary students "were somewhat younger than were students in Los Angeles city and county, and even San Pedro, the places from which the students came." Attendance "was better than average," but in "social adjustment, Manzanar's students were in need of continued significant help." According to the Final Report, Manzanar, "industry was good but spotty; initiative, generally weak; classroom participation, poor." Manzanar students presented fewer disciplinary problems than students in outside high schools, and most high schoolers found "that the standard for making an 'A' was higher at Manzanar than it was in their 'back home' school."

Manzanar's secondary school curriculum and instructional courses were similar to that found in the public schools. Five types of diplomas were offered: general, college entrance, commercial, homemaking, and agriculture. Manzanar did not have organized outlines for all of its courses, however, and this proved to be "a real handicap."

The secondary teaching staff was composed of appointed personnel and evacuees, the former comprising the majority. The evacuee teachers generally did not hold teaching credentials, although most of them had some teacher training. Evacuee teachers decreased in number much more quickly than did the student population. Turnover was rapid, and replacements were difficult to find.

Appointed teachers, all of whom held teaching credentials, worked closely with the evacuee teachers. Approximately one-half of the Manzanar high school teachers were California-trained and credentialed, the majority receiving some or all of their education at the Berkeley and Los Angeles campuses of the University of California and the University of Southern California. The center experienced difficulty in retaining teachers because "of the year-'round period of service required (as contrasted with the 10-month or shorter period in most public schools)." The ratio of one teacher to 35 high school students was below "the accepted minimum standard" for secondary schools, a situation that presented administrative difficulties in scheduling work loads. The center's inability to employ substitute teachers was also "a serious and an unsolved problem."

The secondary school enrollment "ranged from a high of 1,400 to a final of less than 600." In the standardized testing program the following "facts were discovered." Manzanar students were about "one year retarded as late as a year and a half from the closing of the schools." By June 1945, however, they were "at least average in most subjects, and above grade in some." They continued to be "deficient" in English composition and the "practical use of the rules of grammar." In "spoken language," they made "significant progress but were still retarded in enunciation, pronunciation, stage presence, and the like." In mathematics, they "fared better, but were nevertheless weak in general mathematics achievement in the upper grades." They were "slightly below average" in "comprehension, reading rate, and related areas."

At the conclusion of the first school year (1942-43), commencement exercises for Manzanar High School took place outdoors during the early evening of July 3, 1943. The emphasis of the program was on relocation and Americanism. Miss Sakuma, the class secretary, spoke on the subject, "Our Next Step — Relocation," urging those who relocate to keep in mind that they are "ambassadors of good will." The class president spoke on "The Problems of Minority Groups," reminding the audience that evacuees should not be bitter, because the problems faced by Japanese Americans were largely those faced by other minority groups. He urged a realistic and brave approach to the entire problem and a sympathetic understanding of the plight of other minority groups rather than preoccupation with the difficulties of those faced by persons of Japanese ancestry alone. Entertainment featured the Manzanar High School Choir singing the "Ballad for Americans," a patriotic piece of music. Taking his theme from the ballad. Project Director Merritt delivered the commencement address, pleading with the audience to remember that "this country is young and strong" and that "its greatest songs are still unsung." To those who asked why the barbed wire, the towers, and the soldiers, he answered that the final word on American race relations has not yet been stated. He recalled the vision of an America composed of many peoples who have given of their talents and asked the graduates to believe in America. Turning to relocation, he asserted that the country needed and wanted the "God-given talents of those of Japanese ancestry for work, for family loyalty, for the creation of the beautiful." [30]

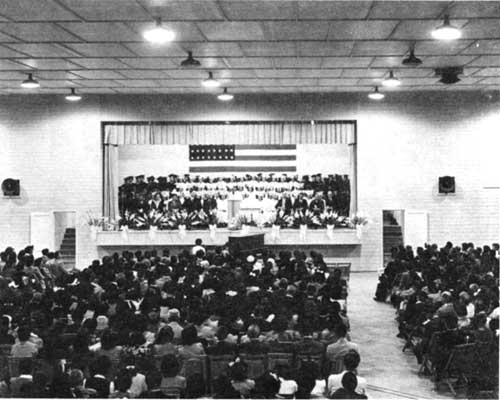

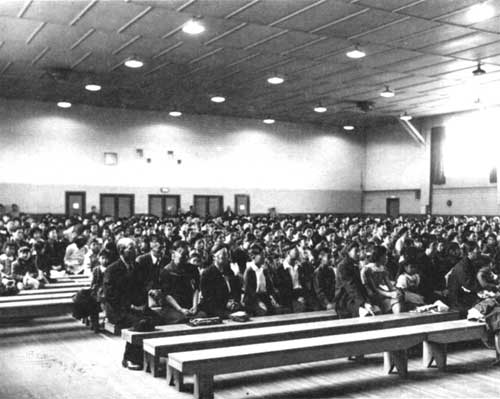

One of the first events to be held in the newly-completed auditorium was the graduation ceremony for 177 seniors on June 18, 1944, Approximately, 1,200 evacuees and appointed personnel attended the event. Clad in traditional caps and gowns, the graduates received their diplomas from Superintendent of Education Genevieve Carter. Assistant project director Lucy W. Adams greeted the class and introduced the commencement speaker. Dr. Cecil Dunn, professor of economics at Occidental College, who spoke on the topic of "Peace and Our Responsibilities." [31]

Of the approximately 500 high school graduates from Manzanar, "not one was rejected by a receiving school for credits earned" at the center. A "better-than-average success" was also achieved by high school graduates who entered college. [32]

Adult Education Program

Following the outbreak of violence at Manzanar on December 6, 1942, the adult education program was reorganized into three sections. These divisions included adult English for non-English-speaking groups; academic courses for those who wished to attend classes at the junior college level; and cultural courses for those who desired to study for personal development and improvement.

On January 11, 1943, adult education classes resumed with approximately 1,500 students enrolled in more than 30 courses. Attendance quickly dwindled, however, as a result of the registration, relocation, and seasonal furlough work programs. In January 1943, some 630 young people of college age were enrolled in 24 academic courses, but by the middle of March, some 320 students had dropped out and six courses had to be discontinued for lack of students. When the semester ended in June, less than 200 students, mostly female, were still attending classes.

During the summer of 1943, the adult education program, under the leadership of Dr. Melvin Strong who had replaced Charles K. Ferguson as director, introduced more commercial courses to help students better qualify for educational or employment opportunities outside the center in an effort to stimulate relocation and yet keep students sufficiently interested in attending classes. The courses, designed at the junior college level and accredited by the California State Department of Education, were offered especially for those contemplating relocation to outside schools. New classes were added to the adult English group, and vocational training in woodcarving, tailoring, librarianship, agriculture, and cosmetology were introduced.

During the remainder of 1943 and early 1944, the adult education program was affected by a shortage of teachers, as five evacuee instructors departed for Tule Lake and 11 relocated. Of the original group of evacuee teachers, only six remained. By recruiting evacuees and soliciting the aid of some appointed personnel teachers, the adult education program continued. Under the direction or Miss Dorothy Yamamoto, 15 young women were enrolled in apprenticeship training in a "cosmetology school."

In April 1944, Miss Kazuko Suzuki assumed temporary leadership of the adult education program after Strong resigned. Two months later, Dr. Kenneth L. Wentworth arrived at the camp to direct the program. In May, an auto mechanics course was introduced, and 24 students registered. By mid-June the course had become so popular that more than 60 students had registered for future classes. The department "saw the need for more vocational courses," but these plans never materialized because Wentworth left the center in late June after serving only a month, and the vocational training supervisor terminated in October.

During the summer of 1944, student relocation counseling became a part of the adult education program. Materials were collected for some 600 trade schools and institutions of higher education, and students and parents were encouraged to use them.

On September 1, 1944, Dr. Gladys C. Schwesinger arrived at Manzanar as Supervisor of Adult Education, and Henry W. Hough took over the work of Vocational Training Supervisor. Hough would stay at the center for only three weeks, however, thus continuing the rapid turnover in program leadership.

During late 1944, a shortage of instructors and "an attitude of indifference on the part of the residents" hindered development of the adult education program. An Adult English Activity Hall was opened, however, offering cooking demonstrations and craft activities conducted by both evacuees and Caucasians who used English "as the medium for exchanging ideas." Emphasis was placed "on enabling the evacuees to mingle informally with English-speaking Americans, to learn their language functionally, and to acquire American points of view and ways of doing things."

In February 1945, Dr. Schwesinger transferred to the community welfare section, and the adult education program "tapered off." The few remaining evacuee teachers were preparing to relocate, most of the evacuee college-age persons who had been evacuated to Manzanar had already relocated to attend schools or work on the outside or serve in the armed forces, and many parents were contemplating relocation at the end of the school term. During the summer of 1945, however, classes were offered in "brush-up commercial courses, adult English, cabinet-making, and tailoring." [33]

Libraries

The original Manzanar library, which was established in an evacuee's living quarters during April 1942 with a gift of 17 books and 80 magazines, expanded to include a collection of 24,000 volumes (20,000 volumes were donated by other libraries) and a periodical subscription of 157 magazines. Originally organized under the recreation section, the library was transferred to the education section in July 1942. By autumn the several branches of the library were consolidated into the main library in the center of the camp and a branch fiction library in the southwest corner of the center. Takako Saito served as director of the library from April to July 1942, and Ayame Ichiyasu served as director from July 1942 to January 1943.

In October 1942, the school libraries were organized. The high school library was established first, as books from the community library were transferred to the mess hall in Block 7 which was converted for use as a study hall. The supervisor of student teaching organized a small professional library of more than 200 books in her office for loan to student teachers and regular teaching staff in the elementary and secondary schools. In November 1942, children's books were ordered for an elementary school library and placed in the elementary teachers' study room for teachers to borrow for use in their classes.

In June 1943, following the arrival of Ruth Budd, a trained librarian on the appointed staff, the libraries were reorganized. A central library office was established in Block 7, and a centralized union catalog of the holdings in all libraries was commenced. The professional and elementary school libraries, originally independent units, were placed under the direction of the community librarian. The two book collections were moved into the same room, and two evacuee librarians were added to the staff to direct the new library.

A three-unit weekly staff training program in library science was commenced for evacuees, and when a student completed the entire course, he was classified as a trained assistant A total of 39 persons entered the course "at one time or another," but only 14 completed the three units, primarily as a result of the continuing relocation of evacuees.

The main library was located in one entire barrack in the center of camp. It was equipped with six mess hall tables, benches, and a camp-constructed charging desk and card catalog cabinet, and had a seating capacity for 50 readers. This library "was invariably crowded at night." It contained both fiction and non-fiction titles for adults and children until November 1944. That: month all "easy books" were transferred to the elementary school library. In January 1945, the juvenile non-fiction volumes were divided between the elementary and high school libraries. Fiction for junior and senior high school students, as well as adult fiction and non-fiction titles, remained in the central library, which also contained a Japanese language collection of 994 books. Mending of all library books was handled by an evacuee at the main library. The main library was never completely catalogued, in part because of the large number of volumes and the "problem of weeding out several thousand worthless books that were placed on the shelves at a time when hundreds of donated and discarded books were sent into the Center."

A branch fiction library, known as the hilltop library, was located in an ironing room in the southwest corner of the camp. It contained 1,453 catalogued fiction books, approximately one-half of which were for adults. Two mess hall tables for adults and two small painted tables for children provided a seating capacity for 18 persons. This library "was a favorite spot for young people to gather" on "cold winter evenings," because the "two librarians" made "it into a very attractive place."

In June 1944, approximately 350 volumes and several hundred pamphlets were moved from the teachers' study room to be housed with the newly-established professional-visual aids library. Located in "the visual aids room," this library "contained over 3,000 mounted pictures, maps, models, exhibits, films, charts, and phonograph records." The microphone and motion picture projectors were placed in this room. The library also subscribed to education periodicals, and the librarian supervised the visual education museum in Block 8, Building 15,

The high school library had a seating capacity of approximately 300 and a catalogued collection of about 3,000 titles. The preschool library, with 169 catalogued books, was handled by the preschool supervisor.

In June 1944, Block 16 was set aside for the elementary school. The elementary school library, consisting of 2,791 books, was moved from the teachers' study room in Block 1 to a room in one of the barracks in Block 16. The room, which was decorated by an evacuee mother, was opened to children on July 5, and 240 youngsters visited the facility on its first day of operation. The average daily attendance was about 200 children. A summer reading club was begun, with 197 children joining the club and 120 reading the ten books required to obtain a membership certificate. After school started in September 1944, each elementary class was scheduled for one library instruction period per week. Because many children had been unable to bring toys to the center when they were evacuated to Manzanar and many toys were unavailable because of wartime restrictions or evacuees' financial difficulties, a toy loan library was attached to the elementary school library in which toys could be borrowed for seven-day periods.

During the summers of 1943 and 1944, outdoor story hours for elementary school children were conducted twice a week during the evenings. During the school year, story hours were held on Saturday mornings, separate sessions being held for children aged three to six and for older children aged seven to eleven. [34]

Hospital Class

One full-time credentialed teacher, with experience in exceptional children's education, supervised classes for handicapped children at the Manzanar hospital. Conducted in cooperation with the medical section, the classes originated within the elementary school program. At one time, two credentialed evacuee teachers assisted the program, but both relocated to teach outside the center before the school program ended. [35]

Summer Programs

A primary purpose of the summer program in 1943 was to provide opportunities for make-up school work on both the secondary and elementary levels. Only the children whose grades and achievement test scores indicated a need for remedial work were scheduled for academic classes. All other children were enrolled for activities which "gave them a different type of group experience from any offered during the academic school year."

Another part of the 1943 summer program was "the offering of step-up subjects, a schedule of courses on the secondary level which enabled half-year students to complete work necessary to enter school the following fall on an annual basis." Some 470 students were enrolled in subjects, such as English, mathematics, and history. At the close of the high school summer session, members of the graduating class received their diplomas, thus making it possible to end mid-year graduation and have only one senior class the following year. Thus, all Manzanar high school students went on a regular annual school year basis when classes started in September 1943.

During the summer of 1943, a boys' sports program was organized in connection with the Boys' Club Center. Different hours of activity were scheduled for various age groups. The secondary school girls were offered a sports program two evenings a week, while other secondary school activities continued "in the form of clubs such as the Baton Twirlers' Club, the Arts and Crafts Class, the Choir Club."

Approximately 450 elementary school children attended a 6-week school program during the summer of 1943 "which stressed drill in school subjects." In addition, some 425 pupils were enrolled in one or more classes in the activities program — "in industrial arts, general arts, music, drama, rhythms, and dancing." Sewing and knitting classes, and "other applied arts activities" were also offered.

All nursery schools and kindergartens conducted summer activities until August 27, 1943 with programs that followed much the same schedule as that of the regular school year. Greater emphasis, however, was placed on "play activities at the kindergarten level."

The summer program for 1944 was supervised by the community activities supervisor who worked closely with the superintendent and principals of the education section. Approximately one-half of the center's high school students preferred to work during the summer rather than engage in daytime activities. For secondary school students, attendance in make-up classes was compulsory for students who had received a D or F in English. Other classes that were offered included mechanical drafting, typing, shorthand, speech, and woodshop.

During the summer of 1944, a reading program in connection with organized book clubs on the elementary level "was unusually effective." Stenciling, knitting, and sewing classes were offered, and Junior Red Cross clubs on the junior high and elementary levels were active.