|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER THIRTEEN:

THE ROLE OF THE MILITARY POLICE IN PROVIDING EXTERNAL SECURITY FOR THE MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION CENTER

In early May 1942, the first persons of Japanese ancestry began to arrive at the relocation centers operated by the War Relocation Authority from the assembly centers administered by the Wartime Civil Control Administration. By June 5, when the movement of evacuees from their homes in Military Area No. 1 into assembly centers was completed, the transfer of evacuees to relocation centers was well underway There were, however, two exceptions to this phase of the government's evacuation program — Manzanar and Poston. Both camps had been established initially by the Army as "reception centers" to serve not only as assembly centers but also as permanent relocation centers. The former, which is the focus of this study, had been opened as the first assembly center by the WCCA on March 21 but was transferred to the WRA on June 1 to become an officially-designated relocation center. As the government's evacuation program continued, provision for the external security of both the assembly and relocation centers by military police units was developed by the Western Defense Command.

DEVELOPMENT OF POLICIES TO PROVIDE FOR EXTERNAL SECURITY AT ASSEMBLY AND WAR RELOCATION CENTERS WITHIN THE JURISDICTION OF THE WESTERN DEFENSE COMMAND: 1942

First Order Governing Function of Military Police at Evacuation Centers, April 15, 1942

On April 15, 1942, the first order governing the functioning of military police units at evacuation centers (a term covering both the assembly and "reception" centers then being administered by the WCCA) and the relationship of those units with the centers' civilian managers or directors was issued by Lieutenant General DeWitt, Commanding General of the Western Defense Command. The order included a brief statement outlining the purpose of the centers:

They [the evacuees] have been moved from their homes and placed in camps under guard as a matter of military necessity. The camps are not 'concentration camps' and the use of this term is considered objectionable. Evacuation Centers are not internment camps. Internment camps are established for another purpose and are not related to the evacuation program.

According to DeWitt's order, the centers were "operated by civilian management under the Wartime Civilian Control Administration." Civilian 'police available will be on duty to maintain order within the camp." Responsibilities of the civilian police would include "search of individual evacuees and their possessions for contraband" and 'escort of visitors and evacuees throughout the camp." The camp director was responsible 'for all means of communication within the camp.

The order described the functions of the military police at the evacuation centers. These included:

The military police are assigned to the Center for the purpose of preventing ingress or egress of unauthorized persons and preventing evacuees from leaving the Center without proper authority. The Assembly Centers in the combat area are generally located in grounds surrounded by fences clearly defining the limits for the evacuees. In such places the perimeter of the camp will be guarded to prevent unauthorized departure of evacuees. The Relocation Centers are generally large areas of which the evacuee quarters form only a part of the Center. These Centers may have no fences and the boundaries may only be marked by signs. At such Centers the military will control the roads leading into the Center and may have sentry towers placed to observe the evacuee barracks. The balance of the area may be covered by motor patrols. The camp director will determine those persons authorized to enter the area and will transmit his instructions to the commanding officer of the military police. The camp director will determine those persons authorized to enter the area and will transmit his instructions to the commanding officer of the military police. The camp director is authorized to issue permits to such evacuees as may be allowed to leave the Center.

In case of disorder, such as fire or riot, the camp director or interior police are authorized to call upon the military police for assistance within the camp. When the military police are called into the camp area on such occasions the commander of the military police will assume full charge until the emergency ends. The question of the disposition of unmanageable evacuees is not a responsibility of the military police.

The commanding officer of the military police is responsible for the black-out of the Evacuation Center. A switch will be so located to permit the prompt cut-off by the military police of all electric current in the camp. He will notify the camp director of his instructions relative to black-outs.

The commanding officer of the military police is responsible for the protection of merchandise at the post exchanges furnished for the use of the military personnel.

Enlisted men will be permitted within the areas occupied by the evacuees only when in the performance of prescribed duties.

All military personnel will be impressed with the importance of the duties to which their unit has been assigned, the performance of which demands the highest standards of duty, deportment and military appearance.

A firm but courteous attitude will be maintained toward the evacuees. There will be no fraternizing. Should an evacuee attempt to leave camp without permission he will be halted, arrested and delivered to the camp police.

Commanding officers of military police units will be furnished copies of operating instructions issued to the camp director. They are required to maintain such close personal contacts with the camp director and his assistants as will assure the efficient and orderly conduct of the camp, and the proper performance of the duties of each. [1]

Establishment of Organizational Responsibility for Implementation of External Security Provisions

DeWitt outlined the organizational arrangements of the Western Defense Command to implement the aforementioned order in the U.S. War Department's Final Report, published in 1943. The Commanding Generals of each Sector of the Western Defense Command were responsible to DeWitt for the external security at each of the centers located in their respective Sectors. One or more military police companies were assigned to each center as required by the area and evacuee population.

The Sector Provost Marshal was responsible for the actual supervision of the military police at all centers in his Sector. The Provost Marshal, Western Defense Command, advised the Commanding General, Western Defense Command, in matters pertaining to external security at the centers, and prepared the policies and orders of the Commanding General for transmittal to the Commanding Generals of the various Sectors. The Provost Marshal, Western Defense Command, as well as other officers from that headquarters, periodically inspected the manner in which announced functions and policies were carried out by the military police companies at each of the centers. [2]

External Security Provisions in Memorandum of Agreement between the War Department and the War Relocation Authority, April 17, 1942

On April 17, 1942, War Department and the War Relocation Authority officials signed a Memorandum of Agreement delineating the responsibilities of each in the implementation of the government's program to evacuate persons of Japanese descent from the west coast to assembly centers and ultimately to relocation centers, the latter to be administered by the WRA. Section 9 of the Memorandum of Understanding provided for external security measures at the relocation centers by the military:

In the interest of the security of the evacuees relocation sites will be designated by the appropriate Military Commander or by the Secretary of War, as the case may be, as prohibited zones and military areas, and appropriate restrictions with respect to the rights of evacuees and others to enter, remain, or leave such areas will be promulgated so that ingress and egress of all persons, including evacuees, will be subject to the control of the responsible Military Commander. Each relocation site will be under Military Police patrol and protection as determined by the War Department. Relocation Centers (Reception Centers) will have a minimum capacity of 5,000 evacuees (until otherwise agreed to) in order that the number of Military Police required for patrol and protection will be kept at a minimum. [3]

Civilian Restrictive Orders and Public Proclamation No. 8

Subsequent to the aforementioned Memorandum of Agreement, the Western Defense Command issued a series of Civilian Restrictive Orders and Public Proclamation No. 8 in compliance with its terms. On May 19, 1942, Civilian Restrictive Order No. 1 established all assembly and relocation centers in the eight far western states under its jurisdiction as military areas from which evacuees were forbidden to leave without express written approval by the Western Defense Command. Succeeding Civilian Restrictive Orders Nos. 18, 19, 20, 23, and 24 described the boundaries of the various centers.

Public Proclamation No. 8, issued by the Western Defense Command on June 27, 1942, further assured the external security of the relocation centers. Under its terms all center residents were required to obtain a permit before leaving the designated center boundaries The proclamation specifically controlled ingress and egress of persons other than center residents. Violations were made subject to the penalties provided under Public Law 503, 77th Congress.

Four of the ten war relocation centers were established outside of the Western Defense Command and hence outside the jurisdiction of the Commanding General, Western Defense Command. To secure uniformity of control, the War Department published Public Proclamation WD:1 on August 13, 1942. This proclamation designated the Heart Mountain, Granada, Jerome, and Rohwer relocation centers as military areas and as War Relocation Project areas. In addition, it contained provisions similar to those of Public Proclamation No. 8 relative to the ingress to and egress from relocation centers. [4]

Memorandum of Understanding as to Functions of Military Police Units at the Relocation Centers and Areas Administered by the War Relocation Authority, July 8, 1942

In July 1942 a "Memorandum of Understanding As to Functions of Military Police Units at the Relocation Centers and Areas Administered by the War Relocation Authority" was developed to prescribe the functions of military police units at relocation centers within the jurisdiction of the Western Defense Command. It was signed by E.R. Fryer, Regional Director, WRA, on July 3, and by Karl R. Bendetsen, Colonel, G.S.C., Assistant Chief of Staff, Civil Affairs Division, for the Western Defense Command on behalf of DeWitt. The memorandum defined a "center" or "relocation center" as "a community administered by the War Relocation Authority pursuant to the provisions of Executive Order No. 9102, issued March 18, 1942." The term "area" or "relocation area" meant "the entire area which surrounds and includes a relocation center, which is under the general administrative jurisdiction of the War Relocation Authority, and which has been designated a military area pursuant to Executive Order No. 9066, issued February 19, 1942." The lengthy memorandum, which incorporated much of DeWitt's first order issued on April 15, contained sections dealing with: (1) the purpose of relocation areas; (2) freedom of movement of evacuees; (3) functions of the project directors; (4) functions of civilian and military police units; (6) conduct of enlisted men; and (7) cooperation between commanding officers of military police units and the WRA:

Purpose of Relocation Areas — Relocation areas have been established for the purpose of caring for Japanese who have been moved from certain military areas. They have been moved from their homes and placed in relocation areas as a matter of military necessity. . . .

Freedom of Movement of Evacuees — Japanese evacuees in the relocation centers should be allowed as great a degree of freedom within the relocation areas as is consistent with military security and the protection of the evacuees. In general, the evacuees will have complete freedom of movement within the relocation areas from sunrise to sunset. From sunset to sunrise the evacuees will not be allowed beyond the center limits without the special permission of the project director. The boundaries of the relocation centers and areas shall be marked, respectively, by signs in both the English and Japanese languages indicating their limits.

Functions of the Project Directors — Relocation centers are operated by civilian management under the War Relocation Authority. A project director is in charge of each center. The project director will determine those persons authorized to enter the area and will transmit his instructions to the commanding officer of the military police. The project director is authorized to issue permits to such evacuees as may be allowed to leave the center or area.

Functions of the Civilian Police — Civilian police will be on duty to maintain order within the area; to apprehend and guard against subversive activities, or undercover crimes and misdemeanors; to make such search of the person and property of the Japanese evacuees as may be necessary to guard against the introduction or use of articles heretofore or hereafter declared contraband; to control traffic within the center; and to enforce camp rules and regulations.

Functions of the Military Police — The military police on duty at relocation centers and areas shall perform the following functions:

a. They shall control the traffic on and the passage of all persons at the arteries leading into the area;

b. They shall allow no person to pass the center gates without proper authority from the project director;

c. They will maintain periodic motor patrols around the boundaries of the center or area in order to guard against attempts by evacuees to leave the center without permission. The perimeter of the relocation area shall be patrolled from sunrise until sunset and during such other times as the commanding officer of the military police units deems advisable. The perimeter of the relocation center shall be patrolled only from sunset to sunrise;

d. They shall apprehend and arrest evacuees who do leave the center or area without authority, using such force as is necessary to make the arrest;

e. They shall not be called upon for service in apprehending evacuees who have effected a departure unobserved;

f. They shall be available, upon call by the project director or by the project police, in case of emergencies such as fire or riot. When called upon in such instances, the commanding officer of the military police unit shall assume full charge until the emergency ends.

g. Conduct of Enlisted Men — Enlisted men will be permitted within the areas occupied by the evacuees only when in the performance of prescribed duties. A firm but courteous attitude will be maintained toward the evacuees. There will be no fraternizing.

h. Cooperation between Commanding Officers and the War Relocation Authority — Commanding officers of military police units will be furnished copies of operating instructions issued to Project Directors. The Project Directors and their assistants and the commanding officers will maintain such close personal contacts with each other, as will assure the efficient and orderly operation of the area, and the proper performance of the duties of all. [5]

Circular No. 19, Policies Pertaining to Use of Military Police at War Relocation Centers, September 17, 1942

On September 17, 1942, Circular No. 19, "Policies Pertaining To Use of Military Police At War Relocation Centers," was promulgated by the Headquarters, Western Defense Command and Fourth Army Reiterating many of the aforementioned provisions for external security at the war relocation centers, the circular formalized and amplified the earlier policy statements. Section 3 of the circular stated that the "boundaries" of the "War Relocation Project Areas" within the territorial jurisdiction of the Western Defense Command, including Manzanar, "shall be marked with appropriate signs in both [the] English and Japanese language." The circular stated that the provisions of Public Proclamation No. 8 "require that those Japanese persons evacuated to a War Relocation Project Area shall remain in that area, except as movement is authorized in writing by this headquarters, transmitted through the War Relocation Authority." Violations of these provisions were "subject to prosecution as provided by Public Law No. 503, 77th Congress."

Section 4 of the circular noted that a War Relocation Project Area comprised the "entire area" of a relocation center, including "the populated area and the administrative and industrial area." Relocation centers were not concentration camps" or "internment camps. While the relocation program "up to the present time has related particularly to the Japanese, the same program may be extended to other civilians as military necessity may dictate."

Section 5 of the circular stated that the project director of each relocation center "will determine those persons authorized to enter the center or the area, other than evacuees being transferred by War Department authority." The project director was "authorized to issue permits to such evacuees as may be allowed to leave the center or the area." He "will transmit his instructions regarding passes and permits to the commanding officer of the military police unit."

Section 6 of the circular stated that "Civilian police, operating under the Project Director, will be on duty to maintain order within the area; to apprehend and guard against subversive activities; or undercover crimes and misdemeanors; to make such search of the person and property of the evacuees as may be necessary to guard against the introduction or use of articles heretofore or hereafter declared contraband."

Public Proclamation No. 3, which had been issued by the Western Defense Command on March 24, 1942, designated "certain articles of contraband which are denied to all persons of Japanese ancestry within the limits of this command."

Section 7 of the circular stated that each relocation center "will be under military police patrol and protection as determined by the War Department." Military police escort guard companies had been assigned to duty at each of the relocation centers in the Western Defense Command.

Section 8 of the circular listed seven functions that the military police units were to perform at the relocation centers. These were:

a. They shall control the traffic on and the passage of all persons at the arteries leading into the area;

b. They shall allow no person to pass the center gates without proper authority from the project directors;

c. They will maintain periodic motor patrols around the boundaries of the center or area in order to guard against attempts by evacuees to leave the center without permission. The perimeter of the relocation area shall be patrolled from sunrise until sunset and during such other times as the commanding officer of the military police units deems advisable. The perimeter of the relocation center shall be patrolled only from sunset to sunrise;

d. They shall apprehend and arrest evacuees who do leave the center or area without authority, using such force as is necessary to make the arrest;

e. They shall not be called upon for service in apprehending evacuees who have effected a departure unobserved;

f. They shall be available, upon call by the project director or by the project police, in case of emergencies such as fire or riot. When called upon in such instances, the commanding officer of the military police unit shall assume full charge until the emergency ends;

g. They shall inspect parcels and packages consigned to evacuees at those centers where the inspection is directed by the Commanding General, Western Defense Command. Special instructions for such inspections and for the confiscation of designated items of contraband will be issued by the Commanding General, Western Defense Command.

Section 9 of the circular stated that evacuees "in the relocation centers should be allowed as great a degree of freedom within the relocation area as is consistent with military security and the protection of the evacuees" In general, the evacuees "will have complete freedom of movement within the relocation area from sunrise to sunset," "From sunset to sunrise, the evacuees will not be allowed beyond the center limits without special permission of the project director." "Sentry towers, with flood lights, may be placed outside of the boundaries of the center to assist the military police in maintaining proper control." [6]

Delegation of Responsibility for External Security of War Relocation Centers from Western Defense Command to Ninth Service Command, November 22, 1942

On November 22, 1942, DeWitt issued a memorandum delegating responsibility for all external security of the war relocation centers within the jurisdiction of the Western Defense Command to the Commanding General, Ninth Service Command, with headquarters at Fort Douglas, Utah. The memorandum stated that "all persons of Japanese ancestry" had been transferred "from Assembly Centers operated by the Wartime Civil Control Administration under the control of this headquarters, to War Relocation projects, operated by the War Relocation Authority." Effective immediately, war relocation centers outside of the Western Defense Command were "of no further concern of this headquarters." The memorandum stated that the Commanding General, Ninth Service Command was designated "as the agent responsible for the enforcement of all security measures in connection with these projects, and for the enforcement of such parts of Public Proclamations 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 11 as apply." Thereafter, the Ninth Service Command and the WRA were "to deal directly" with each other "on all matters pertaining to these projects without further reference to Western Defense Command." Escort guard companies "presently on duty at these projects" were "assigned to the Ninth Service Command." All matters "concerning the operation of these projects for which the War Department is responsible under the Memorandum of Agreement dated April 17, 1942," would "be handled directly between the War Relocation Authority and such agencies as the War Department may designate." The Commanding General, Western Defense Command, however, would be "kept informed as to instructions issued and agreements entered into, under this directive." The war relocation centers at Manzanar, Tule Lake, Poston, and Gila River "are within the evacuated area of the Western Defense Command and, therefore, have a special status and are of particular concern to this headquarters." Accordingly, the Commanding General, Ninth Service Command, was directed to "provide for immediate reports to this headquarters of any incidents occurring within these centers involving disaffection or riot on the part of center residents in order that appropriate instructions may be issued to provide for the security of the evacuated area whenever such action appears necessary.

The memorandum indicated that the policies outlined in Circular No. 19 issued on September 17, 1942, would govern the military police unit activities under this delegation of authority Policies regarding (1) authorization to issue permits for ingress or egress from war relocation centers, (2) emergency employment of Japanese evacuees outside of the centers within evacuated areas of the Western Defense Command, and (3) parcel inspection at the centers issued by the Western Defense Command on August 11 and 24, September 13 and 21, and October 29, were attached to the memorandum as "statements of policy."

Authorization to Issue Permits for Ingress to and Egress from War Relocation Project Areas, August 11, 1942. On July 8, 1942, the Assistant Chief of Staff, Civil Affairs Division, on behalf of the Commanding General, wrote a letter to the Regional Director and Executive Assistant and all WRA Project Directors and Assistant Project Directors governing policies for authorization to issue permits for ingress to and egress from WRA areas. This authorization letter was superseded by a memorandum to the WRA director from the Western Defense Command on August 11, 1942. Pursuant to sections 3 and 4 of Public Proclamation No. 8, issued by DeWitt on June 27, 1942, this memorandum delegated to the WRA director, and "to each person whom such Director may designate in writing, to grant written authorization to persons to leave and to enter War Relocation Project Areas." Each "authorization shall set forth the effective period thereof and the terms and conditions upon and purposes for which it is granted." The Commanding General, however, retained "the jurisdiction to and this grant of authority shall not authorize the Director, War Relocation to permit" (1) release "of persons of Japanese ancestry from any relocation center or project area for the purpose of private employment within, resettlement within, or permanent or semi-permanent residence within Military Area No. 1 or the California portion of Military Area No. 2," or (2) travel "of persons of Japanese ancestry within Military Area No. 1 or the California portion of Military Area No. 2." Release or travel "shall be by authority of the Commanding General under permits issued by or under authority" of the Civil Affairs Division of the Western Command.

Delegation of Authority to Issue Permits for Ingress to and Egress from Relocation Areas, August 24, 1942. On August 24, 1942, WRA Director Dillon S. Myer issued a directive designating and authorizing 'the Regional Director of the Pacific Coast Region of the War Relocation Authority, and all Project Directors and Assistant Project Directors" to "grant written authorizations to persons to leave and to enter the particular relocation area or areas over which they have, respectively been authorized to exercise jurisdiction." No authorization to enter a relocation area "shall be for a period in excess of 30 days."

Parcel Inspection at Certain War Relocation Authority Projects, September 13, 1942. On September 13, 1942, DeWitt issued a memorandum to the Commanding General, Communications Zone, concerning "Parcel Inspection" at the Tule Lake, Manzanar, Poston, and Gila River war relocation centers. Each of these relocation centers was located "within areas evacuated of persons of Japanese ancestry," thus necessitating "establishment and maintenance" of "security measures not currently requisite at other relocation centers."

Section 2 of the memorandum provided "for contraband inspection of all packages destined for delivery to any center resident (any person of Japanese ancestry or the non Japanese spouse of any such person who is a center resident)" at the four relocation centers. Inspection was to be accomplished by the military police stationed at each of the centers. Inspection was "applicable to all such packages irrespective of the method of delivery and will be inclusive of parcel post and express." In all cases it would "precede delivery to the addressee."

Section 3 provided that inspection would be conducted "in a manner which will insure the detection and removal from all such packages of contraband." The following basic requirements were to be observed:

a. Each package will be opened in the presence of the addressee.

b. item of contraband discovered and removed from a package will be labeled and plainly marked. Such label will show the addressee's name and the sender (if the latter is known). Each item of contraband discovered will be appropriately numbered by an identifying serial number.

c. A receipt will be issued the addressee for each item of contraband discovered and removed. Such receipt will bear the identifying serial number previously assigned the item covered.

d. By arrangement with the project director inspection will be conducted in a building at or near the center. The building should be chosen with a view to facilitating the presence of the addressee, the inspection procedure and the delivery of packages.

e. A contraband register will be maintained. Each item of contraband seized will be entered in the register. The descriptive entry may be limited to the assigned serial number. Periodically, contraband so seized will be delivered to the custody of the project director for safe keeping. A covering receipt reflecting the serial numbers of the items delivered will be obtained from the project director.

f. No item of contraband will thereafter be delivered to a center resident without the express permission of this headquarters.

Section 4 of the memorandum delineated a lengthy list of "articles, commodities or things" that were considered contraband. The list included those items "the use, possession or operation of which are prohibited by paragraph 6, Proclamation No. 3, of this headquarters." Among these items were "firearms, weapons or implements of war or component parts thereof, ammunition, bombs, explosives or the component parts thereof, short-wave radio receiving sets having a frequency of 1,750 kilocycles or greater or of 540 kilocycles or less, radio transmitting sets, signal devices, codes or ciphers, cameras.

Also listed as contraband were "articles, commodities or things" the "use, possession or operation of which are prohibited by Public Proclamation No. 2525, promulgated by the President of the United States on December 7, 1941." These items included 'papers, documents or books in which there may be invisible writings; photographs, sketches, pictures, drawings, maps, or graphical representation of any military or naval installations or equipment or of any arms, ammunition, implements of war, device or thing used or intended to be used in the combat equipment of the land or naval forces of the United States or of any military or naval post, camp, or station." The provisions of this category of contraband were subject to the following exceptions:

. . . . (1) First class mail will not be inspected; (2) Magazines, periodicals, newspapers and books printed in the English language by publishers in the United States and transmitted as second class mail by the original publisher to such person of Japanese ancestry will not be confiscated or withheld as contraband. . . . If, however, such magazines, periodicals, newspapers and books have been mailed by a person other than the original publisher to such person of Japanese ancestry then the same shall be searched for contraband which may be secreted between the pages or covers thereof and in the event any such contraband is found, the same together with the container thereof, shall be confiscated and disposed of. . . .

Section 5 of the order stated that the "tools and implements of an artisan or of a professional person of Japanese ancestry" were "not absolute contraband," and thus were "not subject to confiscation." These items included "wood-working tools, agricultural implements, dressmakers or tailors trade tools, and mechanics tools." The memorandum observed that it was "not intended to prevent the development of skills, crafts, trades and professional endeavors within relocation centers."

Section 6 of the directive noted that the WRA "has concurred in this order and has agreed to provide for the issuance of appropriate instructions to each project director affected." The instructions would "direct the discontinuance of current postal, express, or other parcel delivery service and in lieu thereof the delivery of all packages to military police for inspection."

Emergency Employment of Japanese Evacuees Outside of War Relocation Authority Projects Located within Evacuated Areas of Western Defense Command, September 21, 1942. The Western Defense Command issued a directive to the Commanding General, Ninth Service Command and Communications Zone, on September 21, 1942, concerning emergency employment of Japanese evacuees outside of the four relocation centers located within the evacuated areas under its jurisdiction. The directive stipulated that the Western Defense Command did not object to such employment of evacuee labor provided "the points outlined" were "understood and observed." Accordingly the following information was to be furnished to each commander of military police units stationed at the four centers:

. . . . Evacuee labor may be used by project directors at locations not within the boundaries of the Relocation Project under the following conditions:

That the work to be done is essential to the operation of the project and involves meeting a current emergency.

That payment therefor is not to be received from private individuals or private firms — that is, that it is not 'private employment'.

3. That military guards are to be furnished to prevent the unauthorized absence of evacuees from the area in which the work is to be performed. This is not to be construed as indicating that the military personnel is to act as guards in connection with the work party. Military personnel is to be provided solely for the purpose of controlling exits from the particular area involved in order that unauthorized departure of evacuees may be prevented.

4. In the event an evacuee laborer does escape or does effect an unauthorized absence from the area, the military personnel assigned to secure the area are not to take action for the apprehension of the individual. The Military Commander is, however, to immediately notify local county and state civilian law enforcement officials and the nearest office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In addition, thereto, an immediate report of the occurrence is to be made to this headquarters.

Authorization to Issue Permits for Ingress to and Egress from War Relocation Project Areas for Purposes of Emergency Hospitalization and Incarceration, October 29, 1942. On October 29, 1942, the Western Defense Command issued a directive to Dillon S. Myer, the WRA Director, supplementing the authority granted in the aforementioned memorandum of August 11, 1942. Under the October 29 memorandum, authority was delegated "to the Director, War Relocation Authority and to each person not of Japanese ancestry" that he designated "in writing, to grant written authorization for persons to leave and to enter War Relocation Project Areas for purposes of emergency hospitalization, institutional detention and incarceration." Each authorization was to "set forth the effective period thereof, if this can be determined, and the terms and conditions upon and the purposes for which it is granted." Complete records were to be kept by the WRA and submitted to Western Defense Command headquarters as well as the commanding officer of the military police company on duty at the individual project in question. [7]

MILITARY POLICE UNIT OPERATIONS AT MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION CENTER: 1942-45

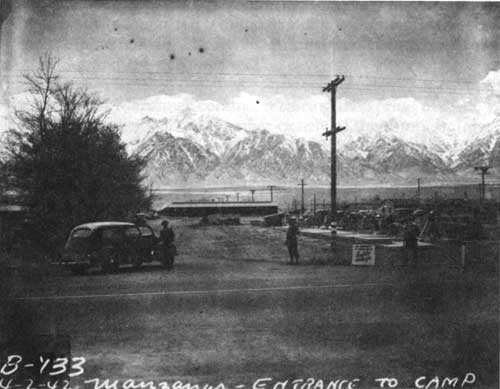

Camp Manzanar

As aforementioned in Chapter Eight of this study, a group of buildings, referred to as the "Military Police Group" and generally known as the "military camp" or "Camp Manzanar, was constructed "south and immediately adjacent to the Relocation Center, separated by a five-strand barbed-wire fence." The military encampment was separated from the relocation center "by an unoccupied open space of level ground about 200 yards from the southerly boundary" of the latter. The facilities were "adequate for one Escort Guard Company of Military Police." [8]

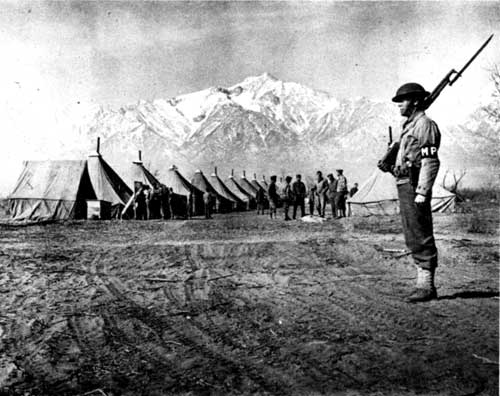

First Military Police Unit at Manzanar: 747th Military Police Escort Guard Company. In a report prepared in early April 1942, Melton E. Silverman, feature writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, discussed the first military police unit to be assigned to external guard duty at Manzanar. Silverman noted that "Lieutenant Harvey Severson and his company of the 747th Battalion of Military Police" had arrived at Manzanar from Fort Ord, a military base located near Monterey, on March 19, two days before the first evacuees arrived at the center. Silverman quoted Severson as claiming that the "men don't like this job." The lieutenant reportedly observed that he could not "blame them very much" "They've been trained and educated to kill Japs, and here they're supposed to protect them."

Silverman went on to describe his perception of the military police during the first several weeks of the camp's operation. He stated:

Many of the military police had never seen Japanese before. They had come from Texas, Montana, South Dakota, Iowa, North Carolina, and New England. The Japanese were strange to them, and so were California, the deserts, the Indians from the reservation farther north, the huge snowy Sierra.

At first, during the early days of the camp, they had a chance to meet some of the Japanese — particularly the Japanese girls, but when the evacuees arrived in large numbers, the soldiers were ordered not to talk to their charges.

They were limited almost entirely to guard duties, guarding the entrance to the camp, patrolling its border [In compliance with their general orders, the military police guarded only the exterior boundary of the relocation center, maintaining only one sentry inside the center at the main gate [9] ], standing by when each trainload of Japanese arrived and assisting in the first registration and induction. Even when relieved of their duties each day, they were not permitted to visit at Manzanar. To them, more than the Japanese, Manzanar was a concentration camp.

Silverman also noted that residents in nearby Owens Valley towns were irritated by the behavior of some of the military police. One of the military police had 'accidentally" killed a fellow soldier at Manzanar, necessitating an investigation by the county coroner at the taxpayers' expense. [10]

Investigation of Military Police, May 1942

In late May 1942, J. A. Strickland, Assistant Chief, Interior Security Section, conducted an investigation of the military police at Manzanar for the Western Defense Command. After his investigation, he reported on his findings which were passed along to his superiors and to WRA officials in Washington.

During the investigation Strickland contacted law enforcement officials in Independence, Lone Pine, and Bishop, as well as District Attorney George Francis. Assistant District Attorney John McMurray, and Superior Judge William D. Dehy in Independence. The "consensus of opinion" of these men, according to Strickland, was that "the Military Police [enlisted personnel] at Manzanar are misfits." The men he talked to had "no love for the evacuees, but they did not "think it proper nor becoming to the Army to have a man going around the county bragging about having shot" an evacuee who had strayed outside the fence at Manzanar. Private Edward Phillips, the military policeman who shot the evacuee, was "guilty of this in his talks" with individuals. Private Beckmeyer, "who seems to be subject to St. Vitus dance or some disease that causes a continuous jerking of the muscles," made local law enforcement officials nervous," and they were "all afraid of this man being trusted with a gun." The law enforcement officials did "not ask for the best that the Army has to guard the evacuees," but they believed "that we should have at least average Army men entrusted with this duty." Discipline between the officers and the enlisted personnel of the military police company was "not at par with Army regulations." The enlisted men, 'while on duty at the center, as well as while visiting the towns, are oftentimes untidy, dirty and slovenly in appearance.

Strickland commented on the relationship between the military police authorities and the interior police at Manzanar. He found this relationship to be "satisfactory," "close cooperation being maintained by both groups." The relationship between "the Center Manager and the military authorities," however, seemed "to be strained from the Center Management side." According to Strickland, Roy Nash, the first WRA Project Director, left "the burden of discipline completely to the Army," while he was "desirous of allowing total freedom to the evacuees.

Concerning the relationship between the military police and the evacuees, Strickland noted that since "the shooting of the evacuee by the Military Police, the evacuees have enclosed their feelings in a shell." The evacuees were "resigned to the fact that the military authorities are in charge and that they will be punished or shot if they venture across the sentry lines." However, there was the feeling that although "the evacuee who was shot was wrong in being beyond the sentry line, even though given permission by the sentry, after he had been shot and no punishment directed toward the patrolman, at least the patrolman should not be allowed the freedom of the county in which to brag about the shooting." This information "came from an evacuee in the center who had not been outside and his information must have been open to the evacuees in the center." [11]

Construction of Guard Towers (also referred to as Observation or Watch Towers)

On May 7, 1942, War Relocation Authority officials visited Manzanar as negotiations were underway for transfer of the center from the Wartime Civil Control Administration to the WRA to become effective on June 1. Following the visit, John H. Provinse, chief of the WRA Community Services Section reported to WRA Director Militon Eisenhower that it was proposed

to install during the coming week 8 observation and guard towers on the project in order to facilitate the military patrol work. Inasmuch as our direction of effort should be away from surveillance of these people as enemies or as anything else than participant American citizens, it seems extremely undesirable to establish such guard towers. Mr. Fryer [who accompanied Proinse] said that he would do everything he could to prevent their erection. In case they are erected while the project is still in Army control, they could be removed after the War Relocation Authority takes over, or they could be allowed to remain without being used. The military contingent at the present time consists of one company of 99 men and patrols are established around the external confines of the project. . . . [12]

By early June the towers were under construction despite WRA objections. The Manzanar Free Press carried a somewhat disingenuous article on June 6 reporting on the progress of the construction:

Have you noticed those towers going up around this center and wondered whether those incipient skyscrapers were the prelude to a carnival or a fair?

Upon being interviewed, Lt. C. L. Durbin, of the 747 Military Police explained that they were watch towers and that six to eight are now under construction.

Following the arrangements at other centers, these towers will be modelled after them in providing improved visibility to the watchmen and providing further security to the residents.

Lt. Durbin also declared that a wire fence will be put up in front of the center. However, along the border of the other three sides, red pennants are to mark the limits of this community. [13]

On July 31, Project Director Nash delivered a speech to the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco during which he outlined the responsibilities of the military police at the camp as well as the measures that had been taken to ensure its external security. Among other things, he noted:

The Relocation Center is that district, approximately a mile square, in which all the buildings of Manzanar are located. It is fenced with an ordinary three-strand barbed-wire fence across the front and far enough back from the road on either side to control all automobile traffic. Four towers with flood lights overlook the Center; the Relocation area is the whole 6,000 acre tract of which the Center is but a part.

. . . . There is a company of Military Police stationed just south of the Center, whose function it is to maintain a patrol about the entire area during the day; and to man the towers and patrol the Center at night. A telephone is being installed in each tower so that if a fire breaks out, it can immediately be reported. The whole camp is under the eyes of those sentries. While evacuees are required to be within the camp itself, there is no curfew. [14]

322nd Military Police Escort Guard Company, June 1942

During June 1942, the 322nd Military Police Escort Guard Company, was transferred to Manzanar, replacing the 747th which had provided external security at the camp since March 19. Most members of the military unit were recruits from New York and New Jersey. Like the members of the 747th, most of the recruits in this company had no prior experience with Japanese, and for many it was their first glimpse of Japanese. [15]

On July 8 Sergeant George Reed of the 322nd suffered severe burns on his right arm and leg as a result of a gas tank explosion at the military compound at Manzanar. He was taken to the Manzanar hospital and placed under the personal care of Dr. James Goto. It was anticipated that he would be a patient in the hospital for several weeks. [16]

Investigation of Military Police, August 31 — September 1, 1942

After June 1, 1942, when the WRA took over administration of Manzanar, there were an increasing number of complaints about "laxity" in enforcement of camp security regulations under Project Director Roy Nash. Throughout the summer, the military units at Manzanar complained that the WRA was permitting the evacuees to violate orders of the Army. According to a memorandum from DeWitt to Bendetsen on June 19, there seemed to be a distinct attitude of camaraderie and brothership between the camp management and the Japanese. In other words, there seems to be an overly friendly attitude — in the opinion of the officers on duty with the Military Police Company. [17]

Among the accusations of the military police officers were that Nash had issued picnic passes for large groups to leave the center, sent groups out of the center without passes and Caucasian guards, and allowed movement across the center's boundaries after curfew Captain Hall, the commanding officer, attended the camp director's daily conference two or three times a week "as observer, not as a participant." Although guard trucks passed "through camp every four hours posting guard," three "guard towers" were "needed in [the] back" or west side of the center. The guards "in [the] rear" walked "through brush" and were "unable to see much of their area." One "man alone" had "no protection against attack." They were not "able to get replacement bulbs for searchlights" in the observation towers when bulbs burned out. The military police did "not inspect vehicles for contraband." The vehicles were "stopped by [a] gate guard and directed on into camp to [the] Interior Police Station for information as to how to obtain pass." All roads "entering [the] camp have now been closed except [the] main gate." Local residents had informed military police that "when location of [the] camp was announced all local sporting goods houses experienced a sell out of guns and ammunition." Thus, the entire "neighborhood" was a self appointed police force to see that evacuees stay within limits." [18]

As a result of the complaints of laxity by the Army which were submitted to the War Relocation Administration on August 27, the WRA assigned P. J. Webster, Chief, Lands Division, in its San Francisco regional office, to investigate the matter. Webster conducted his investigation during August 31 to September 2 "in order that a report could be furnished the Wartime Civil Control Administration, which would serve as the basis for a communication to the Commanding General." During his investigation, Webster interviewed 36 individuals, 12 of whom were connected with Manzanar. He "drove approximately 100 miles in and around the Relocation Center and as far south as Keeler and as far north as Independence," including "a trip through the agricultural area and west of the Relocation Area where it is claimed that Japanese have been fishing and swimming." He inspected "the military police guard system in operation during daylight hours and at night" and "personally inspected the knives and hatchets."

In his report, submitted to E. R. Fryer, Regional Director, on September 7, Webster listed eight specific claims of WRA laxity" at Manzanar that the Army had sent to the WRA. These included:

That 'there is potential danger to the security of property and materials adjacent to subject alien camp because of laxity in the adequate policing and guarding under the new administration by civilian authority.'

Particular stress is laid on 'vital material supplies and processing equipment' in connection with mining operations near Manzanar and 'potential danger to life and property because of inadequate policing and guarding at subject alien concentration camp. . . .

That 15 to 20 Japanese aliens on many occasions have been seen by 12 persons 'riding in Army trucks driven by a Japanese driver, seldom with a white civilian escort, driving all over the district surrounding the alien camp, in many instances over 30 miles from subject camp.'

That Japanese have been seen fishing and swimming in streams 'at distances of from 3 to 9 miles from the concentration camp with no escort or guards.'

That Mr. Horton, Civilian Chief of Police at the War Relocation Area, had 'collected several large boxes of short handled axes and hatchets, and also large quantities of long bladed knives from male Japanese internees, all of which the new civilian administration had ordered him to return to their owners as their personal property' and that Mr. Horton had refused to do this.

That on Saturday, May 10, 1942, a Japanese, Isami Noguchi, driving a Ford V-S - 1940 Station Wagon with no license plates, parked his car alongside of Military Prohibited Zone sign, which he read, and then walked into the Sierra Talc Ore mill at Keeler and asked why talc ore was considered vital to the war effort. [Noguchi was a world-renowned Japanese American sculptor who was a voluntary relocatee at Poston for a time.]

That Dr. James Goto, — 'now located at the Manzanar Evacuation Center, leaves this Center almost weekly in order to come to Los Angeles to work in the Los Angeles County General Hospital.'

That on August 8, 'six Japs were up here in Bishop wandering about our streets and buying fruits and vegetables in the Safeway Store. — As far as they know' (referring to two white women residents of Bishop who saw these Japanese 'there seemed to be no guard with them.'

Webster's investigation resulted in a number of conclusions. Regarding the above mentioned Claims Nos. 1, 2, and 3, he observed:

While the impression is widespread in Owens Valley, that Japanese evacuees have been riding around in motor vehicles and have been in Lone Pine and Independence unescorted by Caucasian guards, no one could be found who would state positively that he had seen a Japanese under these circumstances. There are a number of instances where Japanese have been, and are being, allowed to leave the Center under guard and permit which could be easily construed by a casual observer as a case of Japanese being out of the Center unescorted.

Webster elaborated that of the 24 persons he interviewed who had no connection to the center, a "number.., started out by saying that it was common knowledge that Japanese were traveling around in trucks and shopping in Lone Pine and Independence without escort." However, "in no case" could he find "anyone who would state positively that they themselves had seen a Japanese under these circumstances."

Webster also related the substance of an interview with Captain Archer and Lieutenant Buckner" who had been transferred to the 322nd Military Police Escort Guard Company at Manzanar in late June. He noted that their joint statement

indicates that actual cases of Japanese either driving cars or visiting Lone Pine or Independence unattended by a white are few or non-existent. These two officers stated that there is no way that a motor vehicle can leave the Center and get to the highway without either passing through the main entrance of the Center or through the Military Police encampment, and that no motor vehicle is allowed to leave or return to the Center without a written pass. Military Police guards are requested to carefully check every pass without fail, and it was my experience that this procedure was rigidly adhered to even to the extent of requiring Mr. Nash himself to present his pass.

These officers further stated that they had received numerous complaints that Japanese were riding around outside of the Center or were visiting Lone Pine or Independence without guard. On such occasions these officers told the person making the complaint that all they had to do under these circumstances was to call them on the 'phone and that they would come immediately and take such Japanese into custody However, there has not been one single instance in which anyone has made such a report.

These two officers stated that before they were assigned to Manzanar, at the end of June, they believed that the Japanese had more freedom to go to and from the Center. They stated that they were rigidly enforcing their instructions regarding permits for anyone to leave and return to the Center. Without exception the number of Japanese who have been checked out of the Center checks out exactly with the number that have returned to the Center. In other words, there are no Japanese unaccounted for.

Concerning Claim No. 4, Webster noted:

There is little doubt that Japanese have done considerable fishing and some swimming outside of the Relocation Area and, in all probability, some fishing is being done at the present time.

Webster observed that each "of the twenty-four persons interviewed, who are not connected with Manzanar, were asked if they had any first-hand knowledge of fishing or swimming by Japanese evacuees." Most of the interviewees said "that they believed that fishing and swimming were being done by the Japanese; but there were only two cases where anyone said they had first-hand knowledge of fishing; and no one had personally seen any Japanese swimming."

In one case, E. B. Austin, an employee of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, reported that on August 22 he caught an evacuee fishing along Shepherd Creek, two miles west of the relocation center. This evacuee had told Austin that he often fished in the creek and that "many of the Japanese" fished in the stream. The evacuee told him a friend of his was fishing one-half mile west because the fish were larger there. The evacuee had a "bag" that Austin "estimated held from 35 to 50 fish." Austin had reported the incident to the military police and the local game warden, but both men had done little, the guard stating that "he frequently heard that the Japanese got out of the Center with a permit on detail and then sneaked away and went fishing."

Chief of Internal Police Horton told Webster that "he had no doubt that Japanese working on the garbage crew had been fishing in the Owens River in connection with their trips east of camp to dump garbage." This "practice of fishing on return trips was so well known that working on the garbage crew was a very popular job and there were many applicants." Although fishing in the Owens River had been halted for about a month, Horton related that "a party of 9 or 10 Japanese were found by the Military Police and Mr. Baxter, County Health Officer, sometime ago fishing 3 or 4 miles west from the Center on Georges Creek." The party had a truck and was supposed to be getting native plants for gardening purposes. They had a permit which allowed them to get past the military police guard and "this was simply a case of their taking advantage of the situation."

Although none of the people interviewed by Webster had seen any Japanese swimming outside the center perimeter, he investigated "places where Japanese could have gone swimming."

Small Dam at Southwest Corner of Center — In late June a small dam about two feet high had been built across Bairs Creek at the picnic ground located at the southwest corner of the center. The pool behind the dam had been used by children "for wading and paddling around." When it was realized that the water from Bairs Creek flowed directly into the Los Angeles Aqueduct, Project Director Nash had issued Project Director's Bulletin No. 7 on July 3, stopping all swimming in any streams that were tributary to the aqueduct. [19] Webster inspected the site "and found that the little two-foot rock dam had been torn down in the middle so that it impounded no water."

Settling Basin — Manzanar Water System — Completed in July, the concrete settling basin, located about one-half mile to the north and west of the center, made "an ideal swimming pool." In Nash's absence, Assistant Project Director Ned Campbell announced in the July 7 issue of the Manzanar Free Press that the entire area west of the center would be open to the evacuees. The news article stated:

Extension of the boundaries to embrace the fields and creeks surrounding the former center confines was announced by Ned Cambell. . .today. The new limits run in parallel lines straight west from the watch towers located on the southeast and the northeast corners of the center, and extend four miles into the foothills. Picnics and outings can now be held at any time although the residents are cautioned to use their own discretion in keeping the grounds clean and observing reasonable hours. Swimming in the creeks, however, is strictly prohibited since they are the source of the Center's water supply Neither will fishing be allowed until permits are received. Strict adherence of the rules must be observed . . . . or the extended boundaries may be revoked. [20]

After this announcement, a group of Japanese went swimming in the settling basin on July 8. The following day the Manzanar Free Press reported that "Permission for camp residents to go beyond the west boundary line up toward the hills was cancelled . . . after complaints were received that people were swimming in the community water reservoir and also in the aqueduct streams." [21]

Shepherd and Bairs Creeks — Webster noted that reports "have been circulating in the Manzanar area that Japanese have built several crude stone and brush dams "in Shepherd and Bairs Creeks "to dam up enough water for swimming." A survey of the creeks on September 2 revealed "a dam approximately 1-1/2 miles west of the settling basin but it does not appear that this was built by the Japanese." On Bairs Creek there were "three small dams which might be used for swimming but which apparently were built before the Japanese came to Manzanar." Six dams, "two of them quite large, which may have been made by the Japanese" were also found on the latter creek. The two larger dams impounded "enough water to permit swimming of a very modest type while the other dams are too small to permit anything but wading."

Los Angeles Aqueduct — Although there was no definite evidence that the Japanese had done any swimming in the Los Angeles Aqueduct, Webster observed that it "would be much more difficult for them to swim here than west of the Center, because of the difficulty of getting to the aqueduct and because the chances of being apprehended are considerable." The aqueduct was "well patrolled by the City of Los Angeles."

Webster reported that he had conferred with Nash regarding fishing and swimming outside the relocation center boundaries. Although not having any first-hand knowledge, Nash "had no doubt that this had been taking place." He thought such activities would "continue unless more guards were assigned by the Military Police to patrol the west boundary of the Center."

Webster also noted that he had discussed the issue with the military police. Captain Archer and Lieutenant Buckner

thought it was possible for the Japanese to leave the Relocation Center and fish or swim. They said they had heard that the Japanese were doing some fishing and swimming west of the Center, but if this were true they were doing it at a very great risk to their personal safety. They said that there were about 120 soldiers in their unit, and this made it difficult to post an adequate guard on the west side, twenty-four hours a day. At the present time. there are 11 guard posts being maintained on a 24 hour basis. Besides this guarding service this unit is expected to carry on a heavy training program.

After speaking with the military police, Webster had personally reconnoitered the west boundary of the center. He reported:

I inspected the guarding service along the west line, which is approximately 7/10 of a mile in length. This area is patrolled, but so lightly that a person could go over the line without being noticed. This is particularly true because there is a trash-burning dump a little distance from the west boundary of the Center. In connection with this dump, a long trench has been excavated and the dirt therefrom forms a long barrier about five feet high. If a person gets over this barrier he can proceed a considerable distance to the west, out of sight of anyone patrolling the west boundary. Furthermore, at night there are no search lights along the west boundary.

Webster elaborated further on his investigation of security measures on the west side of the center. He stated:

On the other hand, the guards have been instructed to shoot anyone who attempts to leave the Center without a permit, and who refuses to halt when ordered to do so. The guards are armed with guns that are effective at a range of up to 500 yards. I asked Lt. Buckner if a guard ordered a Japanese who was out of bounds to halt and the Japanese did not do so would the guard actually shoot him. Lt. Buckner's reply was that he only hoped the guard would bother to ask him to halt. He explained that the guards were finding guard service very monotonous, and that nothing would suit them better than to have a little excitement, such as shooting a Jap.

Another statement which Lt. Buckner made emphasizes the attitude of the Military Police and also that they take the patrol service with the utmost seriousness. He said that he, personally, would not be willing to attempt to cross through the beam of light thrown by one of the four search lights now installed for a thousand dollars, even though he had on his soldier's uniform.

Sometime ago [in May] a Japanese was shot for being outside of the Center. The evidence as to just what happened is conflicting. The guard said that he ordered the Japanese to halt — that the Japanese started to run away from him, so he shot him. The Japanese was seriously injured, but recovered. He said that he was collecting scrap lumber to make shelves in his house, and that he did not hear the guard say halt. The guard's story does not appear to be accurate, inasmuch as the Japanese was wounded in the front and not in the back. This incident is recorded as an indication that, if the Japanese are leaving the Center on the west side to fish and swim, they are doing so at great peril to themselves; and that, if they continue this practice, in all probability one of them will get shot.

Realizing that the patrolling of the west side was not satisfactory, Captain Archer, over a considerable period of time, has been trying to get additional watch towers and search lights. His request has just been approved and plans are now under way for the installation of four more towers, which will make a total of eight. When this installation is completed (the additional four towers would be completed by early November) there will be a tower at each corner, and at the middle point of each of the four sides of the Center. Twelve powerful search lights will be installed which will throw a broad beam of bright light around the entire Center. When this is completed it appears very unlikely than any Japanese will leave the Center without permits during hours of darkness.

As to Claim No. 5, Webster felt that it was "relatively unimportant." "About 50 of the knives and 11 of the hatchets referred to have already been returned to [the] Japanese." The policy has been "to return these articles when it could be shown that they were needed by the Japanese in connections with their regular employment."

In support of this conclusion, Webster summarized the substance of an interview with Chief of Internal Police Horton. According to Webster, the chief related:

When the Japanese began arriving at Manzanar at the end of March, all baggage was carefully searched for contraband. This was in accordance with Army instructions and was carried out jointly by the Army and WCCA. During May and up until [the] WRA took over the project about June 1, the Internal Police were under the direction of Major Ashworth, Internal Securities Section of WCCA. Major Ashworth not only continued this practice of searching the baggage of the Japanese, but he added several items to the list of contraband, including all sharp instruments and flashlights. Prior to Major Ashworth's taking charge no receipts were given to Japanese for any articles collected. This was deemed unnecessary because the Army had no intention of returning these articles. Capt. McCushion gave these instructions. Mr. Horton estimates that the number of articles taken, with no record of the owner, is somewhere between 100 and 150. From May on, receipts have been given by the Internal Securities Section for articles taken and the practice of confiscating such articles is continuing at the present time.

Throughout the entire period a Japanese was allowed to keep any article, such as knives and hatchets, provided that he could show a 'work slip' or 'order' from some properly constituted authority that these articles were needed in the work which he was to perform on the project. For example, a cook with knives necessary for cooking could keep these knives if he could show that he was definitely going to be employed as a cook at the project. Such knives would have to be kept at the place of his job and not at his home. If a Japanese cook was not given a job as a cook when he first came to the project and therefore had to give up his knives but later became a cook, he could reclaim his knives and use them on the job. Mr. Horton estimates that at least 50 knives have been returned on this basis.

Also, about six hatchets have been returned to Japanese working as farmhands and recently about five hatchets have been given out to be used in connection with stone masonry. Mr. Horton explained that his understanding of the policy back of this procedure was that it was an unnecessary risk to have dangerous weapons, which were not necessary to the performance of actual jobs, lying around the homes of Japanese which, in case of a disturbance, might be used to commit personnel injury or damage to property.

Regarding Claim No. 6, Webster could find no record "that a person named Isami Noguchi ever has been registered at the Manzanar Relocation Area." Webster expanded on this conclusion by summarizing the results of a conversation with Nash. The Project Director observed that personnel records at Manzanar indicated that no one by that name had ever been "an inmate" at the camp. However, he stated:

. . . . I recall distinctly Mr. Triggs, who was the Camp Manager under [the] WCCA telling me that before my arrival there had appeared at Manzanar an artist named Mr. Noguchi. I do not recall his first name. He said that this gentleman came voluntarily with introduction from someone on the White House staff, and wanted to teach art in Manzanar and other Assembly and Relocation Centers. Mr. Triggs, for reasons best known to himself, refused admission to Mr. Noguchi, who is at present located in Poston. Whether or not this is the same man, I cannot say.

Concerning Claim No. 7, Webster found no evidence "that Dr. James Goto has left the Relocation Center except on two occasions when he went to Lone Pine attended by a Caucasian." Webster observed that he conferred with both Nash and Goto about these allegations. Nash informed, and Goto confirmed to, him that Goto had left Manzanar "on only two occasions since he entered as an internee." The

first occasion was on Sunday, June 7th, when he and Mrs. Goto were my guests at dinner in Lone Pine in company with Colonel Cress, Assistant Director of the War Relocation Authority. The second occasion was on Monday, July 20th at 2:00 A.M. when the police wakened me to say that the Dow Hotel at Lone Pine made an urgent request that Dr. Goto be permitted to come in to attend a man who was one of their guests who was in extreme pain, no doctors being available in Lone Pine at the moment. I consulted the Commanding Officer of the Military Police and personally drove Dr. Goto to attend the patient. We returned together to Manzanar at 4:00 A.M. Dr. Goto has not stepped outside the Manzanar Center on any other occasion.

In regard to Claim No. 8, Webster noted that in "all probability Japanese were seen in the Safeway store in Bishop on August 8, unattended by a Caucasian, inasmuch as there were 26 Japanese who stopped in Bishop on that date enroute from the Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, Internment Camp to the Manzanar Relocation Area." In response to questioning, Nash had informed Webster:

We have constantly received Japanese both from Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, and from Fort Missoula, Montana (which are Concentration Camps). These people have been coming in from one or the other of these points about every week since I have been here. Our records show that under date of August 8th, 26 Japanese were inducted at Manzanar who arrived here at 3:43 P.M. by Inland Stage, having come from Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, by Union Pacific to Ogden, Southern Pacific to Reno, and thence by stage from Reno to Manzanar. The stage from Reno necessarily comes through Bishop and stops there for nearly an hour. The Japanese who are transported on the stage are under no obligation to stay in the stage during this stop. They are perfectly free to enter any shops they like and I have no doubt that under this date Japanese were seen in the Safeway Store and other stores in Bishop.

The Webster report was submitted by the WRA to the War Department. On October 2, John J. McCloy, Assistant Secretary of War, wrote to Myer, commenting that the "complaints received by Wartime Civil Control Administration are typical examples of how rumors spread." McCloy had sent the report to Bendetsen who had written in response: "The report is comprehensive and indicates that all alleged incidents were thoroughly investigated; it tends to disprove the verity and accurateness of the complaints." [22]

Despite the efforts of the military police and WRA authorities, evacuees would continue to leave Manzanar without required passes throughout the history of the center. In the "Internal Security Section" of the Final Report, Manzanar, John W. Gilkey, Chief Internal Security Officer of the camp from September 13, 1942, until March 1, 1946, observed:

The Project regulation, hardest to prevent, was that of 'going out of bounds,' or, in other words, the act of leaving the Center without a proper pass. The attraction of the mountains for hiking and climbing, the nearby creeks for fishing — not to mention the satisfaction gained from going outside of the Center for a while — were all great temptations to many of the residents. This was true even when the Military Police were stationed in towers guarding the Center with guns and searchlights. The punishment prescribed by the Project court was generally to be put on probation. Much attention was given to publicity against this form of conduct but in spite of all that could be done to prevent it, the 'out of bounds' violation never completely stopped. It is doubtful if even a long jail sentence would have eliminated it entirely. [23]

Reinforcement of 322nd Military Police Escort Guard Company After Violence on December 6, 1942

As discussed in Chapter 11 of this study, the 322nd Military Police Escort Guard Company was reinforced by 50 officers and men from a detachment of the California State National Guard stationed at Bishop during the night following the riot on December 6, 1942. The next day, the national guardsmen were withdrawn after members of A Company, 753rd Military Police Battalion, and D Company. 751st Military Police Battalion, arrived to reinforce and cooperate with the 322nd in patrolling and guarding the camp. Several days after Christmas, the reinforcement units were withdrawn, leaving the 322nd as the sole military police unit at the camp. The activities of the 322nd, as well as of the reinforcement units, are discussed in that chapter.

319th Military Police Escort Guard Company: June 1, 1943

On June 1, 1943, the 319th Military Police Escort Guard Company was assigned to duty at Manzanar, replacing the 322nd that had been stationed at the camp for almost a year. Prior to its assignment to Manzanar, the 319th, commanded by Captain Donald R. Nail, had provided guard service at a nearby "Prisoner of War Camp." [24]

Captain Nail quickly made his presence felt at Manzanar. Since WRA appointed personnel at Manzanar were required to store their guns and ammunition at the military compound, one of Nail's first actions as commanding officer of the military police at the camp was to request all such persons to "call at his office immediately to identify the guns so that he" could "properly tag and record them." [25]

Within two weeks of taking command at Manzanar, Nail requested the WRA to undertake maintenance of the buildings in the military camp, noting that the "former command at this station" had been severely criticized "for not obtaining satisfactory maintenance" of the facilities. He "hoped that the accumulated defects" could be "cured without undue delay," reminding WRA officials of their responsibility under agreements between the Army and the previous year. [26] The problem of appropriate maintenance of the the WRA established buildings in the military camp at Manzanar would continue to be an issue of contention between the military police and WRA officials until the center closed. [27]

Nail also attempted to impress the evacuees at Manzanar with the importance of staying within the center's boundary fences. On July 3, 1943, the Manzanar Free Press published an article in which Nail instructed "residents not to go under the fence to go after baseballs, golf balls, or for any other purpose." When evacuees found it necessary to go outside the fence, they "must use the gates and secure permission from the M.P. on duty." The article noted that Nail had "received orders to enforce this rule." [28]

Changes in Military Police Patrol Procedures, December 1943

Several changes in military police patrol procedures were announced at Manzanar during December 1943. As a result of negotiations between WRA officials and Captain Nail, the military police agreed to withdraw sentries from the gates located above Block 12 and the Manzanar Hospital, thus opening "the gates on the west side of camp for the benefit of the residents to travel to and from the Manzanar cemetery without the complications of the Military Police." The gates would be locked at night, but they would be open between 9:00 A.M. and 5:00 P.M. During the daytime hours, an internal security officer would be stationed at the gate "to inspect the red passes and to allow work crews out." The red passes would be distributed by the block managers.

Manzanar residents, however, were warned "that all persons who go out through those gates must remain within the Manzanar area." The "center area" was "designated by white signs." Any person "found outside of the area" would be "severely dealt with by the project director and the Military Police." If an evacuee violated these regulations, the military police could revoke the "privilege." [29]

On December 25, 1943, approximately one year after the violence at the camp, Project Director Merritt received what he called a "Christmas present" from Captain Nail. Starting on Christmas Day, the military police would no longer patrol the perimeter of the camp or man the gates and guard towers from 8:00 A.M. to 6 P.M. The only exception would be a soldier stationed at the rock sentry house to control traffic at the main gate of the center. This change in procedure was, according to Merritt, a sign of drastic changes in the attitude of the military police toward the evacuees at Manzanar. [30]

Reduction of Military Personnel and Modification of Military Mission at War Relocation Centers, March 28, 1944

On March 28, 1944, War Department officials in Washington submitted to the Western Defense Command proposals for reduction of military personnel at relocation centers within its jurisdiction. The recommendations, which had the concurrence of WRA Director Myer, proposed that henceforth Manzanar, as well as Gila River and Poston, would each have only two officers and one-half of a military police escort guard company assigned to them, whereas Minidoka and Central Utah would each have only one officer and 12 guards. Tule Lake would continue to have one full military police escort guard company to provide for its external security.

Because of the proposed reduction in military personnel at the relocation centers, the War Department recommended changes in the "mission assigned these units" under Section 8 of Circular No. 19, issued on September 17, 1942. The proposed changes included:

The military police would only control the traffic on and the passage of all persons at the arteries leading into the centers rather than the area itself.

Rather than preventing persons from passing through the centers' gates without authority from the project directors, the military police would merely assist WRA authorities in accomplishing this task.

The military police would reduce motor patrols around the boundaries of the relocation areas, but they would maintain at least one motor patrol around the boundaries of the areas each day.

The military police would no longer apprehend and arrest evacuees who left the centers or areas unobserved without proper authorization.