|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER FOURTEEN:

THE LOYALTY CRISIS AT MANZANAR — REGISTRATION, SEGREGATION, AND PARTICIPATION IN THE ARMED FORCES

One of the most significant chapters in the history of evacuation and relocation was the registration, leave-clearance, and segregation programs carried out at all relocation centers during 1943-44. These programs, "one of the most exacting experiences" that the War Relocation Authority would undergo during the war, represented "a fork in the road for the evacuated people — a testing of fundamental loyalties and democratic faiths in an atmosphere of high emotional tension." The program "brought to the surface grievances that had accumulated over a period of months and laid bare basic attitudes that had previously been submerged and indistinct.' Its net results were, according to the WRA, "unquestionably beneficial both for WRA and for the great bulk of the evacuated people." The trauma and turmoil that the efforts to determine evacuee loyalty brought to the relocation centers by these programs, however, would raise serious doubts concerning the credibility of this conclusion. [1]

NATIONAL HISTORIC CONTEXT

Registration Program

Military Background of Program. The military background of the registration program dated to the early phases of evacuation when the U.S. Selective Service System was advised by the War Department to discontinue inducting registrants of Japanese ancestry until further notice. On March 30, 1942, the War Department issued an order, discontinuing the induction of Nisei into the U.S. armed services and placing them in a IV-F classification (unsuitable for military service). At the time there were about 5,000 Nisei from Hawaii and the mainland in the Army, the majority having been drafted. Enlisted Japanese Americans in the Army soon found themselves in a precarious situation. The personal attitude of their commanding officers was decisive; some Nisei stayed in the service, while others were discharged without explanation.

No clear-cut Selective Service policy was established to evaluate the status of draft-age Japanese Americans until June 17, 1942, when the War Department announced that it would not, aside from exceptional cases, "accept for service with the armed forces Japanese or persons of Japanese extraction, regardless of citizenship status or other factors." Later on September 14, the Selective Service adopted regulations, prohibiting Nisei induction and classifying registrants of Japanese ancestry IV-C (declarant and nondeclarant aliens), the same status as that for enemy aliens. [2]

Soon after his appointment as Director of the WRA on June 17, 1942, Dillon Myer came to the realization "that the most important key to the regaining of status" of Japanese Americans "was the opportunity for service with [the] armed forces." Myer believed that participation in the military service was important for two reasons. First, as American citizens, the Nisei should have the same rights and responsibilities as other American citizens, including the responsibility to fight for their country. Second, it was important to the future of the Nisei that they have the opportunity to prove their patriotism in a dramatic manner, and thus regain their rightful place in American society. Starting in July 1942, he began pressing this point home to the Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy and other officials of the War Department. [3]

Myer's efforts would later be reinforced by the Japanese American Citizens League, which in November 1942 petitioned President Roosevelt for reinstatement of the draft for citizens of Japanese descent. The JACL conducted a one-week conference in Salt Lake City in late November 1942, that was attended by representatives from each of the relocation centers. Manzanar's representatives to the conference were Fred Tayama, Joe Grant Masaoka, and Kiyoshi Higashi, all of whom would play important roles in the violence that broke out at the camp less than two weeks later. At the conference, the JACL adopted resolutions declaring that it "its stand on the principles of duty to country and to Americanism is unwavering and holds even greater significance in these times of stress." In addition to asking for reinstatement of Selective Service procedures for Japanese Americans, other resolutions passed included expressions of confidence in the WRA, greetings to Nisei soldiers, commendation to the President of the United States on his selection of liberal personnel in WRA, gratitude to religious bodies for their work on behalf of loyal Americans and residents of Japanese ancestry, and an appeal for funds for recreational purposes in the relocation centers. [4]

During the summer of 1942, the War Department began a program to recruit some American citizens of Japanese descent as 'exceptional cases" under the meaning of its June 17 directive. The Military Intelligence Service (MIS), the intelligence branch of the U.S. Army, realizing that men skilled in the Japanese language would be vitally needed in the Pacific Theater, had established a language school for this purpose at Camp Savage, (and later at Fort Snelling), Minnesota, under the leadership of Colonel Kai E. Rasmussen. During the autumn of 1942, recruiting officers were sent out to all WRA centers in an effort to enlist volunteers among the male citizens at the centers who had a working knowledge of the Japanese language and who demonstrated promise that they could be trained to become language 'experts' in a comparatively brief period of time. The men were recruited both as instructors and translators. Ironically, many of the evacuees at the centers who were able to meet these qualifications were Kibei. a group considered by military and WRA experts to be generally the most disaffected element within the Japanese American population, and the largest number of volunteers came from the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, where "disloyal' sentiments were greatest. By the end of 1942, a total of 167 male American citizens at the centers had met the necessary requirements and were either already enrolled or in the process of being enrolled in the language school at Camp Savage. [5]

Nisei soldiers in the MIS were attached to every major combat unit in the Pacific, including the Alaskan Defense, Southeast Asia Area, Central Pacific Ocean, Southwest Pacific Area, and South Pacific Area commands, as well as the European Command. The Nisei "intelligence" soldiers were attached as individuals to military units in these commands and given noncommissioned ranks, thus depriving them of "proper recognition, awards and promotions." Nevertheless, they made considerable contributions to the American war effort. Due primarily to the work of the MIS, General Douglas MacArthur stated, 'Never in military history did an army know so much about the enemy prior to actual engagement.' General Charles Willoughby, G-2 intelligence chief, said, "The Nisei saved countless Allied lives and shortened the war by two years. [6]

On January 28, 1943, the Secretary of War Stimson announced that the Army had decided to form a special Japanese American combat team and that recruits would be accepted from the relocation centers, the Hawaiian Islands, and elsewhere on the mainland of the United States. In the near future, the secretary added, a special enlistment program to recruit personnel for the team would be carried out simultaneously at all relocation centers. Four days later, President Roosevelt wrote to Stimson, approving the combat team plan and calling it a step toward restoration of the evacuated people to their normal status in American society. By February 6, ten recruitment teams were on their way from the War Department in Washington to the relocation centers, and the 21,000 male citizens of military age in the centers faced one of the most crucial decisions of their lives. [7]

WRA Administrative Background of Program. In early January 1943, when the WRA was first informed of the plans for a large-scale Army recruitment program at the relocation centers, the agency was developing its own plans and strategies to conduct a mass registration of all adults in the centers to speed up the leave-clearance process — the process of determining leave eligibility for evacuees based on national security considerations. Prior to this time, the WRA had attempted carry through its leave and/or relocation policies with little effect because of red-tape involved with the clearance program. Both the Army and the WRA needed much the same type of background information on the people in the centers to conduct their respective recruitment and leave-clearance programs. The Army needed information on male citizens of draft age for induction purposes, while the WRA needed it on all residents 17 years of age and older for leave-clearance purposes. Thus, the decision was made to combine Army recruitment and WRA leave-clearance registration in one massive operation to be carried out jointly by both entities. [8]

Program Implementation. Two basic questionnaires were developed to implement the Army recruitment and WRA leave-clearance programs. One form (DSS Form 304A), titled, "Statement of United States Citizens of Japanese Ancestry," was for male citizens of draft age, while the other (WRA Form 126 Rev.), titled 'War Relocation Authority Application for Leave Clearance," was for all female citizens as well as alien males and females. The questionnaires were complicated and lengthy, each including some 30 questions. The questionnaire titles, wording of questions, and the fact that the Army questionnaire was voluntary while the WRA's was compulsory would lead to considerable misunderstanding and turmoil in all ten relocation centers during the registration program. [9]

The ten Army recruitment teams, each headed by a commissioned officer and staffed by two non-commissioned Caucasian sergeants plus one sergeant of Japanese ancestry, were organized quickly. One representative from the WRA staff at each relocation center (Robert B. Throckmorton, project attorney, was the representative from Manzanar) was brought to the War Department in Washington to be attached to the teams. During January 29 to February 5, 1943, the combined Army teams and WRA personnel were given an intensive course of training at the War Department in the details of handling the registration program at the relocation centers.

During the training sessions, it was decided that the detailed planning and implementation of the registration program at each relocation center would be the joint responsibility of each project director and Army recruiting team captain The Army recruiting teams would administer the military's role in the registration program, while the WRA would be responsible for the registration of female citizens and alien men and women.

At the training sessions in Washington a check-sheet of possible evacuee questions to be asked during the registration program was formulated for the Army recruiting teams. The check-sheet was to be read by a member of the Army team to the evacuees at each relocation center. In the document the possible implications of voluntary enlistment from behind barbed wire were rebutted by such statements as:

The circumstances were not of your own choosing, though it is true that the majority of you and your families accepted the restrictions placed upon your life with little complaint and without deviating from loyalty to the United States. [10]

The WRA did not prepare a similar check-sheet to explain its part of the registration program — an omission that would contribute to the agency's mishandling of its responsibilities.

On February 3, President Roosevelt, who had been informed about the upcoming registration program, sent a letter to Secretary of War Stimson in support of the undertaking. Roosevelt informed Stimson that the program was "a logical step, and no loyal citizen should be denied the democratic right to exercise the responsibilities of his citizenship, regardless of his ancestry" This letter would also be used by the army and read to the evacuees at each center before the registration program began. [11]

The teams arrived at the centers during the first week of February 1943 and immediately arranged for a series of meetings to be held with evacuees in designated messhalls. At these meetings prepared statements were read to the assembly residents regarding the purpose and significance of the registration program, and some minimal efforts were undertaken to answer questions. Actual registration was commenced at most centers around February 10.

At the outset, there was confusion, resentment, and widespread reluctance to register at virtually all the relocation centers. At some centers, such as Minidoka, these initial difficulties were quickly overcome, while at others, such as Tule Lake, they persisted and were even intensified as time went on. Despite the turbulence and the emotional atmosphere that prevailed for varying lengths of time at the relocation centers, the registration program produced useful information to both the Army and the WRA.

The primary benefit in terms of the WRA's administrative needs and ultimate objectives was the accumulation of extensive background information on virtually all adult residents of the centers. For the first time, data required in connection with leave-clearance determinations was readily available on practically everyone who might conceivably apply for indefinite leave. The ground work had been laid for faster processing of leave applications and decentralization of leave procedures, and ultimately a thoroughgoing program to segregate those whose loyalties lay with Japan.

The chief benefit for the Army was the recruitment of 1,208 carefully selected volunteers from the centers by June 30, 1943, the number of volunteers ranging from a low of 40 at Rohwer to a high of 236 at Poston Although this number was a small proportion of the 10,000 eligible that the War Department had estimated and fell short of the 3,000 that it had expected to recruit, those who did volunteer represented from the standpoint of both loyalty and military fitness, "the cream of the draft-age group at the relocation centers." Combined with several thousand volunteers of Japanese ancestry simultaneously recruited from the Hawaiian Islands and enlistment of several hundred Nisei from the mainland outside relocation centers, the volunteers formed the nucleus of "a hard-hitting combat unit." By the end of June, the greater proportion of the volunteers from the centers had entered the Army and were in training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, in preparation for active duty overseas.

The most significant questions asked of the relocation center evacuees during the registration program were Questions 27 and 28 that appeared on both the Army and WRA questionnaires. The two questions on the Army form were to be answered only in front of a representative of the Army recruitment teams, while the other questions were to be filled out with the help of registrars or counselors at each of the centers. On the Army questionnaire, Question 27 asked draft-age males: "Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?" On the WRA form, Question 27 asked: "If the opportunity presents itself and you are found qualified, would you be willing to volunteer for the Army Nurse Corps or the WAAC?" On the Army questionnaire, Question 28, known as the "loyalty question," asked:

Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power or organization?

On the WRA questionnaire, Question 28 asked:

Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power or organization?

Before the registration program had progressed very far at most centers, however, large numbers of alien residents were protesting against the wording of Question 28. Since Japanese aliens were not eligible for naturalization as American citizens, they pointed out that they could not conscientiously answer "yes" to the question as it was worded without becoming virtually "men without a country." On the other hand, a "no" answer could result in deportation. Realizing the logic of this position, the WRA, on February 12, instructed all relocation centers to insert on WRA Form 126 Rev. — "for all aliens but not for female citizens" — the following substitute for the original Question 28.

Will you swear to abide by the laws of the United States and to take no action which would in any way interfere with the war effort of the United States?

Although this change in Question 28 was made to meet the objections of many aliens, other questionnaire problems were never addressed. For instance, the obvious absurdity of asking aliens, especially males, whether they would be willing to enlist in the Army Nurse Corps or the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps was never clarified. [12]

There were a total of 77,957 residents eligible to register at the ten relocation centers. Of this number, 65,078, or 87.4 percent, answered Question 28 with an unqualified "yes," while 5,376 answered "no," 1,041 qualified their answers, and 3,254 failed to register. Including the 234 who did not answer the question, 9,905 Japanese Americans did not answer the loyalty question with a "yes." Thus, approximately 12.6 percent of the total possible reacted negatively to the "loyalty" question The great bulk of the non-affirmative answers came from the citizen group. Approximately 26.3 percent of the male citizens and about 15 percent of the female citizens failed to provide unqualified affirmative answers. Only 3.6 of the male aliens, and 3.5 percent of the female aliens failed to provide unqualified affirmative answers. [13]

Aside from Questions 27 and 28, most of the other questions on the two forms were less controversial. The questions asked for information on topics such as education, previous employment, knowledge of the Japanese language, number of relatives in Japan, foreign investments and travel, religious and organizational affiliations, sports interests, hobbies, magazines and newspapers customarily read, and possession of dual citizenship. As the registration program was completed at the various centers and as the younger residents were subsequently registered upon reaching the age of 17, the completed questionnaires were transferred to WRA headquarters in Washington for cross checking against the records of federal investigative agencies. Under an agreement between the WRA and FBI, the latter took the principal responsibility for this record check and provided the WRA with information on each registrant that was available in its files as well as those of the Office of Naval Intelligence and the Military Intelligence Service. By July 1, some 73,900 cases had been submitted to the FBI, and approximately 61,200 had been returned with available intelligence information. [14]

Evacuee Reactions to the Registration Program. According to the WRA, the underlying factors explaining resistance to the registration program at most centers was "an extremely intricate pattern of influences dating back to the time of evacuation." Two of the most significant factors were "evacuee resentment against the government resulting from evacuation and detention in relocation centers," and "administrative miscalculations and errors of judgment both in the explanation and the execution of the registration program.

At the outset of the registration and enlistment program, most WRA personnel believed that it was "a distinctly forward step for the evacuated people." The War Department's decision to accept Army volunteers from the evacuee population at the centers was regarded as an opportunity for the evacuees to provide the American public with proof of their patriotism and loyalty The registration program was understood to be a practical administrative step taken to speed the return of qualified evacuees back to private life.

To many evacuees, however, both the recruitment and registration programs were understood "in a vastly different light." After undergoing the trying experiences of evacuation and the perplexities of several months' detention in a relocation center, "a considerable minority — particularly among the citizen group — was deeply resentful against the Federal government and highly suspicious of any action it might take affecting their future status." This point of view was reflected, according to the WRA, in some of the "milder" qualified answers to Question 28, such as "Yes, if my civil rights are fully restored" or "Yes, if I can return immediately to my former home. Furthermore, a "yes" answer to Question 28 proved offensive to many Nisei, because it implied that they once had an allegiance to Japan and its emperor. According to the WRA, some of the "most thoroughly embittered citizens tended to regard the whole enlistment and registration as 'just another government trick,' and nearly 3,000 "went to the point of requesting expatriation to Japan."

In hindsight, the WRA recognized that it had handled the program poorly At the time the agency "was so absorbed in the mechanics of an enormous operation that it failed to appreciate the advantages that might have been gained from early consultation with key evacuee residents." There was insufficient time for "adequate advance planning or for the formulation of wholly clear-cut instructions covering every phase of the operation." The confusion that arose about the original wording of Question 28 for aliens was one result of the haste in which the program was formulated.

The linkage of WRA registration and Army recruitment was also understood by the former agency's officials to be "unfortunate." The WRA stated:

. . . . From the very beginning, the recruitment phase of the operation, because of its more dramatic character, tended to obscure the real significance of registration not only in the minds of the evacuees but even in the eyes of many WRA staff members at the centers. And at some of the centers, this initial confusion was never entirely eliminated. It is probably literally true that hundreds of the evacuees went through the registration without any real understanding of the significance of Question 28 or even any adequate appreciation of the reasons why they were being asked to fill out the questionnaires. [15]

Other observers looked behind the responses for reasons to explain the evacuees' reaction to the registration program. These analysts argued that the registration program demanded a personal expression of position from each evacuee, a choice between faith in the future in America and outrage at present injustices. The registration raised the central question underlying exclusion policy, the loyalty issue which had dominated the political personal lives of the Nisei for the past year. Questions 27 and 28 forced evacuees to confront the conflicting emotions aroused by their relation to the government. To illustrate this point, one evacuee later noted:

Well, I am one of those that said 'no, no' on them, one of the 'no, no' boys, and it is not that I was proud about it, it was just that our legal rights were violated and I wanted to fight back. However, I didn't want to take this sitting down. I was really angry. It just got me so damned mad. Whatever we do, there was no help from outside, and it seems to me that we are a race that doesn't count. So, therefore, this was one of the reasons for the 'no, no' answer. [16]

Personal responses to the questionnaire inescapably became public acts open to community debate and scrutiny within the closed world of the relocation centers, thus making the difficult choices excruciating. One young evacuee, for instance, later related:

After I volunteered for the service, some people that I knew refused to speak to me. Some older people later questioned my father for letting me volunteer, but he told them that I was old enough to make up my own mind. [17]

Another evacuee later described his anguish in answering the questionnaire:

Because of the incarcerations, here I was, a 19-year-old, having to make a decision that would affect the welfare of the whole family If I sign, 'no, no,' I would throw away my citizenship and force my sisters and brother to do the same. Being the oldest son and being brought up in the Japanese tradition, it was up to me to take care of my parents, sisters, and brother. It was about a mile to the administration building. I can still remember vividly. Every step I took, I questioned myself, shall I sign it 'no, no,' or 'no, yes?' The walk seemed like it took hours and then when I got there a colonel asked me the first question and I cursed him and answered, 'no.' To me, he represented the powers that put me in this predicament. I answered 'yes' to the second question. In my 57 years, I have never had to make such a difficult decision as that. [18]

Loyalty Review. With the ambiguous results of the registration program in hand, the WRA began to decide who should leave the camps. The WRA's initial leave policies had been in effect for several months. With the results of the registration program, it was now ready to modify these policies. The War Department, however, was not content to leave this matter to the WRA. Despite the continuing protestations that evacuees were a matter for the civilian WRA, the War Department plan of January 20, 1943, called for the formation of a Japanese American Joint Board (JAJB), which would also have a hand in deciding whom to release from the centers. While the WRA would retain ultimate authority over leave clearance, the JAJB would recommend individual releases. [19]

Composed of one representative each from the WRA, Office of Naval Intelligence, Military Intelligence Service, and the Provost Marshal General's office, the board was established to assist in determining the loyalty of American citizens of Japanese ancestry, determine eligibility of applicants for war plant employment, and assist in the selection of volunteers for the Army Early in 1943 the board decided to consider the cases of all evacuee American citizens 17 years of age and older and make recommendations to the WRA on the granting of indefinite leave. [20]

The board floundered in its efforts to determine the "dangerousness" of each evacuee. Finally, an ever-changing system was adopted that would bring an adverse recommendation if any one of a number of "factors" were present. The "factors" included whether the person was Kibei; whether he refused to register; whether he was a leader in any organization controlled or dominated by aliens; and whether he had substantial fixed deposits in Japan. By adopting this approach, the board was spared having to find an illegal or even disloyal act as the basis of recommending continued confinement. Instead, individual characteristics and legal acts became cause for a finding of "dangerousness."

After about a year of making such determinations, as well as performing its other work such as clearing laborers for vital war plants, the board was terminated. It had handled nearly 39,000 cases and made over 25,000 recommendations for leave clearance. Of 12,600 recommendations against release, the Western Defense Command reported that the WRA ignored half of them and released the evacuees anyway. [21]

Participation in U.S. Armed Forces

Selective Service Milestones. Counting draftees, volunteers, and pre-Pearl Harbor enlistees, more than 33,000 Nisei served in World War II, 6,000 of them in the Pacific Theater. During 1943-45, some branches of the military, in addition to the regular Army, were opened to persons of Japanese ancestry On July 22, 1943, for instance, the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps began accepting Japanese Americans. On December 13, the first evacuee girl to be inducted into this organization, Miss Iris Watanabe of the Granada War Relocation Center, was sworn into service in the office of the Governor of Colorado in Denver. [22] Some branches of the military, however, remained closed to Japanese Americans for the duration of the war. The Navy, for instance, did not announce its acceptance of Nisei until November 14, 1945, several months after the war ended. At least one Japanese American served in the U.S. Marines, and several hundred served in the U.S. Merchant Marine. [23]

On January 20, 1944, the Army announced that Selective Service inductions of Nisei would be resumed. As a result, 3,377 men were called before July 1, 1944. Of this number, 1,430 were accepted, 460 were inducted into the Enlisted Reserve Corps, and 194 entered on active duty. Of those called, 188 refused induction, and 106 of them were arrested by officials of the Department of Justice by June 30, 1944. The "great majority answered the call willingly," however, and "the departure of most of the boys" who were "summoned to active duty" were occasions "marked by patriotic demonstrations in the centers."

The principal resistance to the Selective Service developed at the Heart Mountain War Relocation Center where 76 men refused to be inducted, "owing largely to the influence of a group in the community which called itself the 'Fair Play Committee."' The head of this committee argued that it was unjust to draft Nisei until all discrimination against Japanese Americans was eliminated, and the Nisei were admitted to all branches of the Army and Navy on an equal footing with other Americans. These arguments "were cautiously phrased, however, in an effort to avoid statements that might incriminate the committee members." The committee chairman, a U.S. citizen born in Hawaii who had never been to Japan and had no record of disloyalty, was segregated to Tule Lake on April 1, 1944, together with several of his principal supporters. At Tule Lake, he was later taken into custody by the FBI on charges of violating federal sedition and conspiracy laws. [24]

On June 12, 1944, a mass trial for 63 defendants from Heart Mountain began at the federal district court in Cheyenne. Wyoming. Each of the men was charged with violation of the Selective Service Act through failure to submit to a pre-induction physical examination. While acknowledging that the defendants "were loyal citizens of the United States" and that they desired "to fight for their country if they were restored their rights as citizens," the court sentenced all of the men to three years in a federal penitentiary on June 26. About half of the men went to Fort Leavenworth, while the remainder were sent to McNeil Island in Washington. The 63 men remained in prison until receiving conditional releases on an individual basis in 1946.

Meanwhile, on November 2, 1944, seven leaders of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, who had played a leading role in resisting the Selective Service at that relocation center, were convicted of counseling others to resist the draft, but this conviction was overturned by the 10th District Court of Appeals on December 14. Later on December 12, 1947, President Harry S Truman officially pardoned all of the men, and their full citizenship rights were formally restored. Ultimately, 267 persons from all ten relocation centers would be convicted of draft resistance. [25]

On November 18, 1944, the Selective Service established procedures permitting voluntary induction of Issei. Several months later, on March 21, 1945, Kazuo Ono, an evacuee in the Minidoka War Relocation Center, was the first Japanese alien evacuee to volunteer for service in the Army Before being accepted by the Army, he made two unsuccessful attempts to enlist. [26]

On May 28, 1945, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review the decision of a lower court that Americans of Japanese ancestry residing in relocation centers may not refuse draft summons. Less than one week later, on June 1, the U.S. Army ruled that drafted Japanese American soldiers would no longer be placed in the Enlisted Reserve Corps while awaiting call to active service. Henceforth they would be processed in military reception centers on the same basis as other drafted men. [27]

100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team. While Nisei evacuees in war relocation centers were officially prohibited from serving in the U.S. Army on June 17, 1942, an all-Nisei infantry battalion was activated in Hawaii on June 10. Ironically, no mass evacuation or confinement of Nisei in government-operated relocation centers had been undertaken in Hawaii in the wake of Pearl Harbor. [28]

The 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team, which would ultimately develop from this activation, was noteworthy because it was the only Japanese American unit to be established in the U. S. Army. In addition, it was the most highly decorated unit in the Army. The unit also had the honor to be reviewed by President Harry S Truman in July 1945 upon its return to the United States. On July 15, 1946, President Truman would honor the unit with a Presidential Unit Citation. The combined 100th and 442nd suffered 9,486 casualties and won 18,143 individual decorations for valor in battle, including a Congressional Medal of Honor and almost 10,000 Purple Hearts. The casualty rate for the unit was more than 300 percent of its authorized strength of 4,000 men.

The 100th/442nd had an unusual organizational history. One of its units, the Anti-Tank Company, was assigned to a glider assault. The 100th Battalion was also credited for the capture of a German submersible in October 1944. In addition, by rescuing the "Lost Battalion" of the 36th Infantry Division, 442nd members became "honorary Texans." Two of the 442nd members would later become members of the U.S. Senate representing Hawaii during the postwar period — Masayuhi "Spark" Matsunaga and Daniel Inouye.The 100th Infantry Battalion was activated as a six rifle company Separate Battalion on June 10, 1942. The troops consisted of Japanese American members of the Hawaiian Territorial Guard. Because of doubts about its loyalty, the battalion was transferred to the mainland at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, for training, and then was given only wooden guns with which to train. Correspondence of the soldiers was read by military authorities before being mailed. The battalion was transferred to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, in January 1943 to complete its training. The 100th arrived in Oran, North Africa, on September 2, 1943, and was attached to the 34th Infantry. It landed at Salerno on September 26 and participated in the Italian Campaign, fighting as part of the 34th at Cassino. As a result of its accomplishments during the Italian campaign, it became known at the "Purple Heart Battalion." On November 25, Secretary of War Stimson gave the battalion special recognition for its accomplishments during the Italian Campaign, announcing its casualty list, listing decorations, and mentioning high praise accorded the men by their officers.

Meanwhile, in January 1943, the War Department announced formation of the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), and the new unit was activated on February 1, 1943. Upon announcement of the RCT, some 10,000 Nisei in Hawaii volunteered immediately On March 28, the Honolulu Chamber of Commerce held a farewell ceremony in front of Iolani Palace for 2,686 Nisei volunteers for the RCT. The RCT, composed of both Hawaiians and volunteers from the ten relocation centers, began military training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, in May 1943. Later in January 1944 the Selective Service draft was reinstated for Nisei, thus providing additional personnel for the RCT. Comprised of three rifle battalions, an anti-tank company, a cannon company a service company, and a medical detachment, plus the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion and the 232nd Engineer Company (Combat), the only unit to start with Nisei officers, and the 206th Army Band, the 442nd went overseas in May 1943. The main body of the RCT arrived in Naples, Italy, on June 2, and on June 10 it was joined with the 100th Battalion in attachment to the 34th Infantry. After the breakout from Anzio, the RCT soon saw action north of Rome, where the 100th earned a Distinguished Unit Citation for liberating Belvedere, a town south of Florence and the seemingly impregnable Gothic Line. The 442nd stayed in Italy as part of the 34th Infantry until September 1944, when it went to France, landing at Marseilles on September 30. There it was attached to the 36th Division, also known as the Texas Division. The 442nd's Anti-Tank Company was detached to make a glider assault with the 517th Airborne. Soon the RCT was attached to the 36th Infantry for the Rhineland Campaign.

The 442nd fought in the Vosage at Bruyeres in eastern France, and then rescued the Texas "Lost Battalion" (1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th Division). The 442nd's casualties resulting from the daring and highly-publicized relief effort for 211 men from October 15 to November 12 were heavy: 161 killed in action (13 were medics); 2,000 wounded (882 seriously); and 43 missing. Distinguished Unit Citations were awarded for actions at Belmont and Biffontaine prior to the rescue mission.

On November 28, 1944, the 442nd was posted to the French-Italian border with the 100th Battalion, near Monaco. This "Champagne Campaign" lasted until March 1945, when the regiment returned to Italy for the Po Valley Campaign. Attached to the 92nd Division, the RCT broke through the supposedly impregnable "Gothic Line" on April 5, less than one month before the war ended in Italy on May 2. In March the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion was detached from the RCT to participate with the 7th Army in the Central Europe Campaign, where it was among the first American units to liberate the German concentration camps at Dachau. [29]

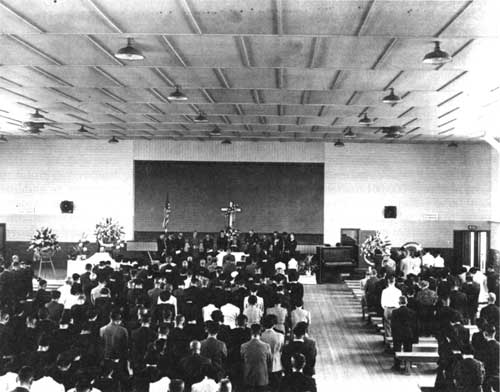

Impact of Military Participation on Relocation Center Life. The movement of young men out of the relocation centers into the armed forces, although numerically small, had a profound impact on life in the camps. By December 1944, for instance, 1,543 men, ranging in numbers from less than 100 to nearly 300 from each center, had been accepted for service and were on active duty. By late 1944 the servicemen had been coming and going from the relocation centers for more than a year, returning to the relocation centers on furlough for visits with their families and friends. They had come back in uniform, and portions of barracks in all centers were established as United Services Organization (USO) entertainment facilities. Thus, the USO facilities became a feature of life in the relocation centers that link them with communities throughout the United States. In the centers, women worked on 1000-stitch belts, in the Buddhist tradition, for the protection of the soldiers on the battlefields. Mothers spent time preparing food for parties, and their daughters arranged dances and other social affairs attended by young people who gathered to socialize with the soldiers. The senryu poets, beginning in 1944, began to write of the uniformed Nisei and the feelings of their parents about them.

At first the coming and going of soldiers affected only relatively few persons in each center, but, many of those affected were parents who had themselves accepted the centers as homes for the duration of the war. Most of the parents of soldiers were men and women who belonged to the core of Issei who had formulated community sentiment. With reopening of Selective Service procedures to the Nisei in January 1944, more and more evacuees began to be affected as sons whose parents had opposed volunteering were taken in the draft. The activities of the USOs were increasingly participated in by at least mothers and sisters of families who had kept their attention averted from resettlement and the outside world. Farewell parties for drafted young men increased. Sometimes these events were merely family affairs, but more and more entire blocks became interested in the young men who were leaving. The recurring farewells became an increasingly prominent feature of relocation center life, and to a greater extent than in outside towns of similar size the whole community began to be affected and to give some recognition to the departing young men.

Inevitably, casualty lists began to have meaning for people in the relocation centers. Sentiment among the evacuees developed that the centers as a whole should pay tribute to the men in uniform. At first there was resistance to such ideas. Gradually, as the WRA administrators encouraged the erection of honor roll tablets listing the men in the armed forces in each center, sentiment swung behind the idea of community ceremonies. Buddhist and Christian ministers and community council chairmen and other evacuee spokesmen arranged ceremonies in honor of Nisei who had been killed. Memorial services became more and more frequent, and interest in them became widespread.

By midsummer 1944 the effects of Nisei participation in the U.S. armed forces on the evacuees in the relocation centers had become marked. For instance, an Issei mother observed in July:

You know things are a lot different than they were a while ago. People really rebelled at the time of registration. They said awful things about the government, and they spoke of the boys who volunteered almost as if they were traitors to the Japanese for serving a country that had treated the Japanese so badly. When Selective Service was re-instituted all one heard was that the government had no right to draft men out of a camp like this. At first when the boys left, their mothers wept with bitterness and resentment. They didn't think their sons should go. This week five have gone from our block. I tell you I'm surprised at the difference. Wives and mothers are sorry and they weep a lot. But now they really feel it is a man's duty to serve his country. They wouldn't want him not to go when he is called. When they talk among themselves, they tell each other these things. They feel more as they did before evacuation. [30]

Congressional Investigations

Prior to January 1943, the War Relocation Authority had implemented its evacuee relocation program with only a limited amount of national publicity. During the first half of 1943, however, as relocating evacuees began to fan out across roughly 75 percent of the country, the program attracted increasing attention from the national news media and Congress.

One of the developments that contributed toward making the WRA evacuee relocation program a national issue was the investigation conducted during January - March, 1943, by a special subcommittee of the Senate Committee of Military Affairs. The seven-member subcommittee, chaired by Senator A. B. Chandler of Kentucky, was appointed to consider the advisability of S. 444, a bill introduced for the purpose of placing the WRA under the administrative control of the War Department. The subcommittee opened its investigation in late January with hearings in Washington, D.C. Following these hearings in the nation's capital, Chandler and a special investigator travelled to the field and continued the investigation at a number of the relocation centers. The last formal public hearing was conducted by Chandler at Phoenix, Arizona, on March 8.

From the public relations standpoint, the investigation took on special significance since it occurred simultaneously with the registration program in the relocation centers. Statements attributed to the subcommittee chairman and others regarding the percentage of negative answers at some of the centers to Question 28 were widely published "without any indication of the background of registration or the climate of human emotion in which it was taking place." The impression created in the minds of the American public by these comments was "that a heavy proportion of the people in relocation centers were actively disloyal to the United States and basically loyal to the Emperor of Japan." Thus, a significant portion of the nation's press and public "became increasingly critical of WRA's policies governing relocation of the evacuated people and operation of the relocation centers."

The subcommittee report itself, however, expressed "only moderate disapproval of WRA activities," and it did not recommend placement of the agency in the War Department. In its final report, approved by the full Committee on Military Affairs on May 7 but not released until July 16, the subcommittee made four basic recommendations were :

That the draft law be made to apply to all Japanese in the same manner as to all other citizens and residents of the United States.

That those who answered 'No" to the loyalty question and those otherwise determined to be disloyal to the United States be forthwith placed in an internment camp, and that such determination should be made at the earliest possible date; and that the cases of those asking for repatriation should be disposed of at the earliest possible date.

That the loyal able-bodied Japanese be allowed to go out to work under proper supervision at the earliest possible time, in the areas where they will be accepted, and where the Army and Navy authorities consider it safe for them to go. . . .

That the proper, necessary Executive and departmental orders be issued to immediately make effective the policies outlined under Recommendations Nos 1 and 3. [31]

On July 3 WRA Director Myer testified before the Chandler subcommittee in executive session and approved California Senator Sheridan Downey's resolution for segregation of "disloyal" evacuees prior to its introduction in the U.S. Senate. Three days later, the Senate adopted Resolution No. 166, asking the President of the United States to order immediate segregation of "disloyal" persons of Japanese ancestry and calling for a public statement on conditions in relocation centers and plans for future WRA operations. [32]

During June 1943, the House Special Committee on Un-American Activities appointed a subcommittee to conduct an investigation of war relocation centers and WRA relocation and segregation policies, as well as evidence of subversion and disloyalty among the evacuee population. The subcommittee was composed of John M. Costello of California, chairman, Herman P. Eberharter of Pennsylvania, and Karl E. Mundt of South Dakota. Led by Congressman Costello who was determined to prove that the WRA was "coddling" disloyal evacuees in the relocation centers, the hearings began on June 8 with sensational anti-Japanese witnesses. Following its highly-publicized investigation during which it was critical of WRA policies, the committee recommended on September 30, 1943:

That the War Relocation Authority's belated announcement of its intention of segregating the disloyal from the loyal Japanese in the relocation centers be put into effect at the earliest possible moment.

That a board composed of representatives of War Relocation Authority and the various intelligence agencies of the Federal Government be constituted with full powers to investigate evacuees who apply for release from the centers and to pass finally upon their applications.

That the War Relocation Authority inaugurate a thorough-going program of Americanization for those Japanese who remain in the centers.The hearings of the Special Committee, as well as those of the Chandler committee, served as a catalyst to spur WRA efforts, already underway, to segregate the "disloyal" evacuees under its charge into a separate center. [33]

Segregation Program

The idea of separating the evacuated people into two groups on the basis of their "fundamental loyalties" stemmed back to the earliest days of the government's evacuation program. During the spring of 1942 Lieutenant Commander K. D. Ringle, Military Attache for the WRA from Naval Intelligence, prepared recommendations for segregation of those evacuees determined to be "disloyal." He urged the agency to conduct a segregation program based on the assumption that the overwhelming majority of "disloyal" evacuees would be found among the Kibei and their alien parents. Under his proposal, all Kibei should be questioned by administrative boards in the relocation centers and "called upon to declare and demonstrate where their natural sympathies lay." This early recommendation for the military's desire to divide persons of Japanese ancestry based on "loyalty," and especially singling out the Kibei for such segregation, would continue to be a theme that military authorities emphasized throughout 1942. [34]

In mid-December 1942 DeWitt proposed a more draconian plan for segregation. His plan envisioned a surprise move by military authorities in which designated evacuees would be gathered, placed aboard trains, and moved to the Poston relocation center, where evacuees not to be segregated would then be removed. The people to be segregated would include those who wished repatriation or expatriation; parolees from detention or internment camps to relocation centers; those with "evaluated" police records during their confinement in assembly or relocation centers; others whom the intelligence services identified as "potentially dangerous;" and immediate families of segregants or wished to join them. The plan, if implemented, would have affected approximately 60,000 persons, or more than half of the evacuee population in the relocation centers. [35]

The WRA, although itself considering segregation, objected to DeWitt's drastic proposals, because they suggested segregating by category and called for secrecy, military control, cancellation of normal relocation center activities, and raised the probability of rioting and bloodshed. Three steps already under way would, the WRA hoped, eliminate the need for segregation: the indefinite leave program; Justice Department custody for aliens whom the WRA believed should be interned; and an isolation center at Leupp for relocation center "troublemakers."

During the spring of 1943, however, pressures from the aforementioned Congressional investigations, War Department officials, and the Japanese American Citizens League, coupled with the larger-than-expected negative reaction to the registration program, provided the backdrop for a WRA-administered segregation program. From the beginning, however, the WRA took the position "that such a separation would have to be made with the utmost care and only after painstaking consideration of each individual case." Thus, once the registration program had been completed and the results had been tabulated, the WRA was "in position for the first time to undertake a really sound and equitable program of segregation."

Several developments indicated "the desirability of such a program" by May 1943. First, the disturbances at Manzanar and Poston in late 1942, together with the turmoil at Tule Lake and other relocation centers during the registration program in early 1943, demonstrated "that serious social tensions at the centers would doubtless continue and perhaps intensify as long as people of sharply diverging loyalties remained quartered close together." Second, many of the evacuees "whose loyalties lay with Japan — those, for example, who had requested repatriation — wanted nothing so much as to remain secluded for the duration of the war." Third, the "admixture of a disloyal minority in the population at relocation Centers was undoubtedly confusing the public mind about the loyalties of the entire group." Once "the patently disloyal had been weeded out," the WRA felt that the "problem of gaining public acceptance for relocation of the remainder would likely be greatly simplified." [36]

At a meeting of the project directors at WRA headquarters in Washington in late May 1943, the major point of discussion was a segregation program. Considerable attention was given to the fact that both "loyal" and "disloyal" elements in the centers were pressing for segregation as a way of alleviating the mounting tensions resulting from the turmoil in the aftermath of the registration program. When a final vote was taken at the end of this meeting, the overwhelming consensus of opinion was for segregation. By a vote of ten to one the final obstacle in the way of another forced movement of Japanese Americans had been cleared. All that remained was the development of procedures for the implementation of the program. The targeted groups and individuals to be segregated included repatriates and expatriates; those with records indicating subversive activities; those who answered "No" to Question 28 or provided seriously qualified answers to the question; and passive resisters. [37]

One of the initial problems faced by WRA administrators in connection with segregation was to find a place where the segregants might be quartered. As early as November 1942, the WRA attempted to find a suitable site for housing repatriates apart from other evacuees, but the search had been unsuccessful. By June 1943, however, the population of the ten relocation centers had dropped to the point where it was possible to designate one of them as a segregation center and to transfer the non-segregant evacuees residing in that center to several of the others. After further consideration, Tule Lake in northern California was selected on July 15 as the segregation center for four principal reasons:

It was one of the largest of the relocation centers with a capacity of approximately 16,000.

It contained extensive acreage readily available for agriculture and thus could provide the segregants with numerous work opportunities.

Its resident population contained a greater proportion of potential segregants than any other center.

It was one of the two centers lying in the evacuated zone and special restrictions imposed by the Western Defense Command made it less desirable than other centers for use as a relocation center. [38]

Whereas the registration program in the relocation centers had been implemented hastily amid confusion and turmoil, planning for the segregation program "was complete and practical." A "Manual of Evacuee Transfer Operations" was prepared by the WRA Solicitor's Office which set forth "a uniform conception of objectives and procedures, outlining a flexible plan of organization of the work entailed at the projects and providing the means of uniformity in essential detail while allowing latitude in project organization to accommodate special circumstances." The procedures "recognized the need of a well-informed staff and a well-informed resident population."

Director Myer and key members of the WRA's Washington staff met with the project directors and their principal staff members at a segregation conference held in Denver, Colorado, on July 26-27, 1943. The purpose of the conference was "to clarify by discussion and unify interpretation of the segregation policy."

At the conference, WRA Solicitor Philip Glick discussed the manner in which those to be segregated would be screened. Three separate types of 'hearings" would be used at each relocation center: segregation, welfare, and leave clearance. The function of the segregation hearings was

to determine that the man really said 'No" to question 28 and knew what it meant and intended to say "No" and still wants to say "No". Or that he refused to register, that he really wants to be Japanese, that the refusal to register was an evidence of his wanting to be Japanese, or that his failure to answer question 28 represents a desire to be Japanese.

The welfare hearings would

be held with the whole family. They will follow the segregation hearing and be held only with families of the segregants. The purpose of the welfare meetings will be to help the evacuees make a choice between centers, answer their travel questions, help them with arranging routine baggage check outs, etc.

The leave clearance hearings were

designed to be as complete an investigation as we can make to enable the director to determine whether a definite leave should be given or whether the person should be interned for the duration. This is a serious problem. Washington will send a docket if available. . . . the Leave Clearance Board will then hold exhaustive hearings, getting a written statement from the evacuee. The ideal way to do this would be to segregate no one until leave clearance hearings had been given, but we can't wait. We have to accomplish the mass segregation of those we are reasonably sure need to be segregated now. We are assuming that the repatriates and expatriates can be segregated now and the 'No's' can be segregated after a hearing to determine what the persons meant. For all others, we don't feel sure enough of our judgment to segregate and to deny indefinite leave unless we do complete elaborate leave clearance hearings. Hearings on them will be completed after segregation and we can determine then whether we have made a mistake. We are recognizing that mistakes will be made however careful we may be. [39]

An official pamphlet entitled, Segregation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry in Relocation Centers, was published by the WRA in August 1943 for distribution to all evacuees and WRA personnel in the ten relocation centers. According to the pamphlet, segregation was for

Those persons of Japanese ancestry now in relocation centers [who] have had the opportunity to state their individual choices and to back their statements by their actions. . . . one of the important sources of information which will be considered will be the answer given by each individual to Question 28 in the registration conducted in each relocation center during February and March, 1943.

The segregation manual outlined the groups of evacuees that would have to attend the segregation, welfare, and leave clearance hearings. Four groups were designated:

Group I. Persons who will be designated for segregation without further hearing. This group includes those persons who made formal application for repatriation or expatriation before July 1, 1943, and did not retract their applications before that date.

Group II. Those persons who, on the strength of their answers to Question 28 or their refusal to answer the question, would appear to be loyal to Japan rather than to the United States. Each of these persons will be asked to appear before a Board of Review for Segregation which will ascertain whether the evidence of pro-Japanese loyalty correctly represents the attitude of the individual. This group includes those who answered "No" to Question 28 and who did not change their answers to "Yes" before July 15, 1943; those who refused to register; those who registered but did not answer Question 28.

The hearings before the Board of Review will be comparatively brief. Those persons found by the Board to continue to hold to their pro-Japanese views will be designated for segregation. Those who sign a statement of loyalty to or sympathy with the United States at the hearings will reclassified to Group III for further hearings on eligibility for leave clearance.

Group III. Those persons who may have stated their loyalty to or sympathy with the United States, but whose loyalty or sympathy is in doubt because of previous statements or because of other evidence. This group includes:

a. Those reclassified from Group II.

b. Those who answered "No" to Question 28 at the time of registration but who changed their answers to "Yes" before July 15, 1943.

c. Those who qualified their affirmative answers to Question 28.

d. Those who requested repatriation or expatriation but retracted their requests before July 1, 1943.

e. Those about whom there is other information indicating lack of allegiance to the United States.

f. Those who have been denied leave by the Director.

Persons in Group III as outlined above will be given hearings by the Leave Section at the relocation center with sufficient thoroughness to enable the Leave Section to determine the true loyalty of each individual, and to decide whether or not he should be declared eligible for leave.

Group IV. Those who are eligible for leave. (Not to be segregated). [40]

In August 1943 a special review board composed of WRA appointed personnel members was established at each relocation center to conduct individual hearings for those persons who had answered the loyalty question in the negative or had failed or refused to answer it. Only those persons who filed applications for repatriation or expatriation to Japan and, as of July 1, 1943, had not retracted them were consigned to the segregation center at Tule Lake without an individual hearing. Each person who had given a negative answer (or none at all) to the loyalty question was asked if he wished to change his answer. If he said that he did not wish to change, the conversation was terminated. On the other hand, if he said that he wanted to change to an affirmative answer, he was questioned extensively as to his motives for changing, and at the close of the hearing the board made a recommendation to the project director for disposal of the case.

Despite the consequences, most evacuees stuck by their original statements and the rehearing process during the summer of 1943 at the relocation centers registered mostly grief, disappointment, and anger. Numerous Issei professed "disloyalty" as a way of getting back to California or of avoiding release. Many Kibei chose Tule Lake out of frustration with official distrust of their group. Others had no choice; they were family members — elderly, children, or handicapped — who could not leave their relatives. A number of evacuees already at Tule Lake embraced "disloyalty" to avoid moving again. [41]

On August 19, 1943, a WRA field station was established at Fort Douglas, Utah, to serve as liaison between the Ninth Service Command of the Army, which was handling the transportation for the segregation program, and WRA officials both in Washington and at the relocation centers. Prior to the first entrainment, a two-day conference was conducted at Fort Douglas, during which all military personnel, train commanders, mess and medical officers, and other staff members received detailed instruction regarding transportation operations.

Between September 13 and October 11, 1943, 33 train trips transported 15,148 evacuees, 6,289 from Tule Lake to other centers and 8,559 to Tule Lake. Each train trip of segregants was accompanied by a military detachment of 50 persons and a WRA staff member whose duty it was to be alert to safety measures, take necessary health and sanitary precautions, answer questions, and delegate to evacuee train monitors and coach captains responsibilities for getting volunteers to work en route and for keeping the railway cars in a sanitary condition. Evacuee volunteers served the regular meals prepared by army cooks, operated the auxiliary diners which furnished meals for the ill and infirm in sleeping cares, and maintained a high standard of sanitation and neatness in the coaches, kitchens, lavatories, and diners. Car mothers looked after children, and formula girls assisted the Army nurses in the preparation of formulas and infant diets. Arrangements for meals en route were made by the Army, with the WRA supplying perishables, fuel for gasoline stoves, and ice for refrigeration. In the course of these train movements, 129,846 meals were served. The Army, at the urging of the WRA, attempted to provide for the comfort and well-being of the aged, sick, expectant mothers, and mothers with small babies. Sickness en route was kept to a minimum, and no deaths or births took place on the trains. Six persons were removed from trains for hospitalization. No case of unrest, violence, disorderly conduct, or intentional resistance was observed by military personnel or WRA train riders on the trains. In view of wartime travel conditions, the service of the railroads was reportedly "excellent in respect to both equipment and schedules." While some trains were delayed in departure beyond their scheduled times, only two reached their destinations later than scheduled.

With one exception the program was conducted according to plan. It was found that housing at Tule Lake could not accommodate the total number of segregants. Consequently, the transfer of approximately 1,900 people from Manzanar was postponed until additional housing units could be constructed. When it became apparent that the movement of the Manzanar people would be delayed until early 1944, one trip was scheduled in early October to move 297 of the Manzanar segregants whose health required that they make the trip before the onslaught of severe winter weather.

During February 21-26, 1944, the second transfer movement of evacuees — 1,876 persons on four trains — from Manzanar to Tule Lake was accomplished. A third transfer movement of evacuees from Jerome, Rohwer, Granada, Heart Mountain, Minidoka, and Gila River to Tule Lake took place on May 4-25, 1944, when 1,654 persons were transferred via four special trains and two special cars on regular trains. [42]

Additional individual segregation hearings continued at the relocation centers, thus ensuring that small contingents of segregants were sent to Tule Lake from time to time. Others would be sent as they failed to convince Director Myer, or his authorized representatives, that they were "loyal" and should be granted leave clearance. All told, the later transfers moved 249 more residents out of Tule Lake, while 3,614 additional segregants transferred in. Altogether, some 6,000 evacuees remained at Tule Lake. Meanwhile, Tule Lake was being physically transformed into a segregation center. A double eight-foot barbed wire fence was erected, the military guard was increased to a battalion, and six tanks were lined up conspicuously on the center's perimeter. [43]

The Solicitor's Office was instrumental in establishing an Appeals Board at Tule Lake for handling cases in which persons denied leave clearance and transferred to Tule Lake might feel that "justice had miscarried." A panel of members for the Appeals Board, consisting of prominent citizens not connected with the WRA, was established, and hearings before the board were set for 1944. The Appeals Board, however, served only in an advisory capacity; the authority to grant or deny leave clearance rested in the final analysis solely with the Director of the WRA. Twenty-four appeals were made prior to June 30, 1944, and were scheduled to be heard by the Appeals Board in July. [44]

While embarking on the segregation program, the federal government also undertook measures to exchange nationals with the Japanese government. On September 2, 1943, the ship Gripsholm sailed from New York for Japan under an exchange of nationals arranged by the State Department, carrying 314 passengers from relocation centers, 149 of whom were American citizens. [45]

During fiscal year 1944, there were 8,981 requests by persons of Japanese ancestry for repatriation and expatriation to Japan, raising the total number of effective requests to 15,366. The WRA reported that a "marked increase in the number of requests for repatriation and expatriation "has followed every major change in government policy affecting evacuees." About 10,000 of the requests

on file were made during or immediately following crises brought about by the Army and leave clearance registration which was conducted in the spring of 1943, the segregation activities of the summer and fall, and the Army announcement on January 20, 1944, that Nisei were to be inducted under Selective Service procedures.

A large percentage of the requests appear to be based more on emotion than reason. The evacuation, the loss of economic security that went with it, and evidences of antagonism outside the centers have filled the evacuees with fear for the future, and any change of policy adds to their alarm. Few of them are motivated to request repatriation or expatriation because they have any real interest in Japan or expectation of going there. They are tired of moving and Tule Lake seems to them the one place where they may be allowed to stay for the duration of the war. They seek segregation to escape pressure to relocate under wartime conditions, to hold their families together, or to protest against the evacuation. Others who do look to a future in Japan have built up fantasies of life there with hardly any actual knowledge of the country they are choosing. [46]

Thus, the registration and segregation programs pushed evacuees in the relocation centers in opposite directions. Some were released and were heading toward a more normal, productive life in American society. To those who expressed their anger and frustration, however, the programs brought a more repressive, violent, and frustrating period at Tule Lake. The programs are appropriately remembered as one of the most divisive events in the camps. It broke apart the community of evacuees by forcing each to a declared choice — a choice that could be made only by guesswork about a very uncertain future. It was a choice that was hard to hedge, and it divided families and friends philosophically, emotionally, and finally, physically, as some went east to start new lives and others were taken off to the grimmer confinement of Tule Lake. [47]

MANZANAR HISTORIC CONTEXT

Registration Program

Program Implementation. The residents of Manzanar first learned of the forthcoming registration program when Assistant Project Director Robert Brown appeared before the Block Managers Assembly on January 29, 1943. Brown emphasized the Army's role in the registration, explaining "that just the Army would arrive and induct the members in this center." [48] Later on February 8, Brown informed the Block Managers that the Army was coming to implement the registration program and that the registration would apply to the entire center. Brown noted:

that they [the WRA] are working out a schedule by which everyone in every relocation center can register for this program. This program does make it easier to get clearance and leave permits for relocation purposes . Therefore, it serves a two-fold purpose. [49]

Lieutenant Eugene D. Bogard, Sergeant Irving V. Tierman, Sergeant James A. Hemphill, and Sergeant Kenneth M. Uni (the members of the Army team who were to supervise registration at Manzanar) were also introduced to the Block Managers on February 8. During the ensuing discussion, Throckmorton, Manzanar's project attorney who had attended the registration program training sessions at the War Department in Washington during the previous week, summarized the thrust of the registration process:

The Army plan is to form a combat unit composed entirely of Japanese-American soldiers, and those who volunteer will be given the opportunity to join this unit. He also mentioned the fact that it is under consideration as to the possibility of Japanese Americans eligible for other branches of the service, and even the AACS for the women. The citizens who are registered in this program will be given recommendation for any type of service if they qualify . . . The military officials are trying hard to get the Japanese back into normal channels. They figure that if the Japanese ate trustworthy enough to join the army, public opinion will favor the actions of the Japanese as a whole. The Army does not expect every loyal person to volunteer, but they will be given an opportunity to declare themselves loyal regardless of whether they are going to volunteer or not. This is the first step towards a solution to this whole evacuation program. [50]

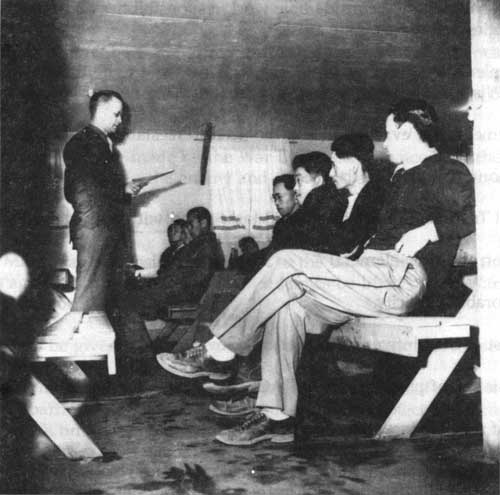

In conjunction with the meetings held for the Block Managers, other meetings were held with the evacuees on a block-by-block basis. At these meetings, the Army team presented the information on its check-sheet. Reiterating the various factors that contributed to the registration program, Lieutenant Bogard stated in the Manzanar Free Press on February 11:

It is the intention of the Army to begin both the reestablishment of the Japanese population as a constructive part of the war effort and also to utilize the registration as a means of demonstrating the loyalty of the Japanese people once and for all. [51]

The actual registration program at Manzanar began on February 12, 1943, with five blocks in the center used as registration areas: one block for the Army team registration, and the other four for the female citizens and the alien males and females. The registration for the latter group was finished in four days, while the former was not completed until February 22 because of the stipulated requirement of having Questions 27 and 28 answered in front of a member of the Army team.

During the registration, the impracticality of Question 28 on the WRA form was quickly realized by the Manzanar appointed personnel. Upon consultation with the Washington Office on February 12, the Manzanar staff was "authorized to change the question in any way [they] saw fit or omit it entirely for aliens." Throckmorton informed Merritt, who was not present at Manzanar during the registration because of an appendicitis attack, what happened next:

Relying upon this verbal authorization. . . . I contacted the Negotiating Committee, consisting of 2 citizens and 2 aliens, in order to obtain its advice as to how the question should be altered for aliens. . . . We immediately agreed the question should be so formed that an alien could answer it in the affirmative without renouncing his Japanese citizenship. . . . the question that was finally agreed upon was as follows: "Are you sympathetic to the United States of America and do you agree to faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces?" [52]

The question as revised by the Manzanar staff was not used until February 13, but because of quick action, the Issei who registered on February 12 were not required to answer Question 28. At the other camps, the reaction of the project directors and their staff was one of wait-and-see for official recommendations or revisions. This waiting policy was well advised, because on the evening of February 13, WRA Director Myer sent telegrams to each center detailing the reworded question as formulated by the WRA.

Myer placed emphasis on the latitude possible in the handling of the question for aliens. He stated in the telegrams that the "substitute Question 28 may also be answered by aliens in a qualified way if they so desire." [53] When Throckmorton received the Myer telegram, he felt that the question formulated by the Manzanar staff was preferable even though he later expressed the opinion that the Manzanar form of Question 28 for aliens was "a strongly worded question." At the time, however, he felt that the Manzanar wording of the question was the best available. [54]

Rather than re-start the registration for the Issei, the Manzanar staff decided to use the question they had devised and at a later date repoll the aliens asking the question utilized at the other relocation centers. This policy was responsible for considerable confusion and misunderstanding for both the WRA and the evacuee population at Manzanar. [55]

Although the Manzanar staff anticipated that the aliens at Manzanar would be able to have a chance to answer the question as formulated in Washington, Project Director Merritt had to request permission for such action. In making this request on March 24, Merritt asked that citizens also be permitted to answer the revised question:

I cannot conscientiously refrain from bringing out this point which will now adversely affect the lives and position of so many of our people, nor can I refrain from urging upon you that we have an opportunity to recanvass the alien groups who have answered 'No" or who have answered "Yes" with qualifications, putting before them another opportunity to cancel their previous reply and answer the revised question sent out by Washington. . . . If this recanvass is permitted by you, I feel certain that we should also then allow our citizens to revise their answer. . . . [56]

At a special meeting of the Block Managers Assembly on March 30, 1943, Merritt solicited the opinion of this group on whether or not the aliens should be re-polled. According to the minutes of the meeting, Merritt explained why Manzanar had used a differently-worded question:

Mr. Merritt said that if the alien residents of Manzanar who answered "No" to Question 28 or gave a qualified answer wish to answer the question as it was asked at the other centers, he would advise the Washington authorities accordingly, and do everything possible to extend them the privilege of doing so. He explained that the reason for the different wording of Question 28 at Manzanar was due to the fact that we completed our registration in four days, and used a wording for Question 28 which was hastily made under pressure of completing the registration, and although Washington approved by telephone, this change of wording from the original wording, which was sent out from Washington gave them an entirely new wording for Question 28. Mr. Merritt stated that this matter is already causing adverse comments between the centers, and they result in unfavorable reactions. He said that for this reason he was laying the whole matter before the Block Managers to obtain their reactions and for them to obtain expression of opinion from the residents of their blocks. [57]

After discussion of Merritt's comments, the Block Managers Assembly agreed that the aliens should be given the opportunity to re-answer Question 28 based on Washington's rewording.

Approval for the re-polling was also received from Washington, and from April 12 to April 24, the 3,500 Issei at Manzanar answered the reworded loyalty question. Of this number, 3,418 or 97.68 percent of the Issei were able to answer the revised question with a "Yes' — a sharp contrast to the responses elicited during the earlier questioning.

As aforementioned, the results of the registration in the relocation centers were well below the expectations of the Army and the WRA. Instead, the number of persons who responded in the negative were surprisingly high at Jerome, Gila River, and Manzanar, and at Tule Lake a large number did not even register. At Manzanar, there were 6,897 persons of 17 years of age or over who filled out one of the two questionnaires. Of that number, 4,269, or 61.89 percent of those questioned, answered Question 28 with a "No' or a qualified answer before the re-polling of the aliens. Those who answered an unqualified "no" numbered 2,645, or 38.35 percent; while those who definitively answered "Yes" were 2,628, or 38.1 percent.