|

Nez Perce National Historical Park Idaho-Montana-Oregon-Washington |

|

NPS photo | |

The way we were taught is that we are part of Mother Earth. We're brothers and sisters to the animals, we're living in harmony with them. From the birds to the fish to the smallest insect.

—Herman Reuben

A Park About a People, for All People

Long before Meriwether Lewis and William Clark ventured west; before the English established a colony at Jamestown; before Christopher Columbus stumbled upon the "new world," the Nez Perce, who called themselves Nimiipuu, lived in the prairies and river valleys of north Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington. Despite the challenges of two centuries of threats and assaults on the Nez Perce homeland, their voices are still heard, strong and resilient. The thread of the past meets the future as the language, culture, and traditions of the Nez Perce move forward through the 21st century.

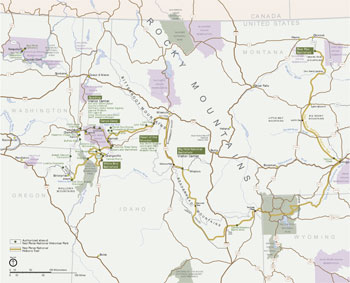

Nez Perce National Historical Park is a park about a people, for all people. It is not one place but many. It is not one story, but a multitude of them. The stories to be discovered are often emotional and sometimes controversial, but they bind us together in a common history and define us as a nation. Today 38 sites in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington commemorate the legends and the history of the Nez Perce and their interaction with others. This includes other Indian peoples as well as the explorers, fur traders, missionaries, soldiers, settlers, gold miners, loggers, and farmers who moved through and into the Nez Perce homeland. As you travel from site to site you will come to sense the rich and diverse cultural history they represent.

The culture and history of the Nez Perce are intertwined with the land they live in. Two sites, Ant and Yellowjacket near park headquarters in Spalding, Idaho, and Heart of the Monster in Kamiah, Idaho, preserve features on the landscape that form the basis of stories relating to the origins of the Nez ship with the land. At Buffalo Eddy along the Snake River outside Asotin, Washington, the ancestors of the Nez Perce left their mark on the landscape in the form of rock drawings or petroglyphs. Weis Rockshelter, close to the Salmon River, near the town of Cottonwood, Idaho, is a site inhabited by the Nez Perce for thousands of years.

Chief Joseph's band lived in the Wallowa Valley in northeast Oregon. The Old Chief Joseph Gravesite is located outside the town of Joseph at the edge of Wallowa Lake. Joseph Canyon Viewpoint, 30 miles north of Enterprise, Oregon, on OR 3, is an example of the canyon-bottomland environment in which the Nez Perce people lived in the winter.

The arrival of the Lewis and Clark expedition triggered an era of change that would have lasting consequences for the Nez Perce. In 1805, after an arduous journey across the Bitterroot Mountains via the Lolo Trail and Pass, the Corps of Discovery, as the group led by Lewis and Clark was known, arrived the historic route Lewis and Clark traveled. Those with a high-clearance vehicle can travel US Forest Road 500, the Lolo Motorway, a primitive dirt road that roughly follows the overland route taken by the expedition.

Lewis and Clark emerged from the mountains on the Weippe Prairie, and came upon the Nimiipuu at a site three miles outside the town of Weippe. Along the Clearwater River, at Canoe Camp, in Orofino, Idaho, Lewis and Clark built the canoes they needed to continue their journey to the Pacific Ocean.

Following in the footsteps of Lewis and Clark came fur trappers and Christian missionaries. Henry H. Spalding built the first Nez Perce mission on the site that is below the visitor center at Spalding, Idaho. The remains of his mission, the Indian Agency it evolved into, and the town of Spalding can be seen. Father Joseph Cataldo established Saint Joseph's Mission, the first Catholic mission in Nez Perce country. The church is still standing, 10 miles southeast of Lapwai.

The establishment of white settlements in the lands of the Nez Perce coincided with the treaties of 1855 and 1863. The treaties divided Nez Perce families and ushered in a period of tumultuous change. Growing resentment over loss of land and unpunished atrocities helped to bring on war in 1877 between the Nez Perce and the US government. The first battle of that war was fought in June 1877 in White Bird Canyon and resulted in a Nez Perce victory. White Bird Battlefield, north of the town of White Bird, can be seen from an overlook off US 95 and a self-guiding trail.

The pursuit of the Nez Perce by troops commanded by Gen. Oliver O. Howard led to the battle at Big Hole in western Montana. In August 1877 soldiers surprised the encampment, killing between 60 and 90 Nez Perce men. women, and children. The National Park Service has preserved the site as Big Hole National Battlefield west of Wisdom, Montana. In October 1877, after a 1,100 chase, the US Army besieged the Nez Perce at Bear Paw, 40 miles from the US-Canada border and brought an end to the war. Bear Paw Battlefield, south of the town of Chinook, Montana, appears much as it did more than a century ago during the last battle of the Nez Perce War.

These are only a few of the sites comprising Nez Perce National Historical Park. An auto tour of the entire park is more than 1,000 miles in length. Many of the 38 sites can be experienced in segments of one or two days travel. Sites associated with the war of 1877 are also part of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail. For information, check the trail's web site at www.fs.fed.us/npnht.

If you intend to stay in Nez Perce country while touring the park's sites, plan ahead. Food, gasoline, and accommodations are not available in the park. Many sites, however, are within easy driving distance of urban centers where services are available. Some al activities such as hiking, picnicking, and viewing wildlife. Opportunities for camping and backpacking, while plentiful in the region, are not available in the park. Inquire locally for information.

Remember: All natural and cultural features are protected by federal and state law.

Nimiipuu

We Have Always Been Here

The prairies and plateaus of north central Idaho, Oregon, and Washington have always been home to the Nimiipuu, as the Nez Perce call themselves. Here they fished the streams, hunted in the woodlands, and gathered the abundant roots and berries of the high plateaus. The Nez Perce traveled widely on the principal rivers of the region—the Snake, Clearwater, and Columbia—to trade with their neighbors. The acquisition of the horse in the 1700s increased mobility, allowing for more frequent travel in company with their Cayuse and Palouse relatives to the Montana bison grounds and Columbia River fishing sites.

During the 1800s the Nez Perce culture underwent profound changes as explorers, fur trappers, traders, missionaries, soldiers, settlers, gold miners, and farmers moved into or through the area. With the arrival of the newcomers looking for land, the Nez Perce, anxious to avoid conflict, met with officials of the US government and agreed to hold treaty negotiations. In 1855 the Nez Perce signed a treaty that created a large reservation that included most of their traditional homeland as their exclusive domain. In 1863, however, following the discovery of gold on the reservation, settlers and miners forced a new treaty that reduced the reservation to one-tenth of the land originally set aside. Some tribal leaders accepted the treaty, but those who stood to lose their land rejected it, giving rise to the "treaty" and "nontreaty" designations of the respective factions.

US government efforts to move nontreaty bands onto the new, smaller reservation led, in part, to the Nez Perce War of 1877. When the war ended, many of the nontreaty survivors were relocated to Indian Territory (in present-day Oklahoma). Eventually some Nez Perce were allowed to return to the reservation at Lapwai, Idaho, but others were exiled to the Colville Reservation. Some Nez Perce also made their homes on the Umatilla Reservation.

The last years of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th were difficult ones for the Nez Perce as white values and culture were forced upon them. The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 gave up to 160 acres of land to individual Nez Perce in the belief that ownership of land would more swiftly assimilate them into the mainstream of American life. The unallotted land was sold to the general public. Soon more than 90 percent of reservation lands was in white ownership.

Today there are Nez Perce living on the Nez Perce, Colville, and Umatilla reservations as well as in towns and cities across the United States. Regardless of where they live, it is the shared heritage of the Nez Perce that unites them as a people.

I never said the land was mine to do with as I choose. The one who has the right to dispose of it is the one who has created it.

—hnmató•wyalahtquit (Chief Joseph)

1877

The Nez Perce bands who refused to accept the 1863 treaty remained in their homeland for several years. In May 1877, however, with settlers clamoring for access to nontreaty lands, the US government told the nontreaty Nez Perce that the US Army would forcibly move them onto the new, smaller reservation if they did not move willingly by June 14.

The leaders of the nontreaty Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Palouse bands, including Young Joseph, Looking Glass, and Toohoolhoolzote, not wishing to leave their homes or to go to war, had hoped for a favorable solution, but to no avail. Before the nontreaty bands could comply with the government order, however, a group of young men, angered by the situation and the lack of justice in murders committed against the Nez Perce, attacked and killed several local settlers.

Fearing reprisal, the nontreaty bands and their allies headed south to a more defensible location near Chief White Bird's village. At White Bird Canyon on June 17, 1877, the Nez Perce inflicted heavy casualties on a superior force of pursuing cavalry. Skirmishes at Cottonwood in early July and a battle on the Clearwater River, July 11-12, proved inconclusive. At Weippe Prairie the nontreaties decided to cross Lolo Pass into Montana. The bands, totaling about 800 men. women, and children, hoped that their friends, the Crow people, would help them out.

More and more soldiers came after them, eventually totaling more than 2,000 infantry and cavalry by the time the war ended. At Big Hole, August 9-10, the Nez Perce lost between 60 and 90 people in a surprise attack under Col. John Gibbon. The relentless pursuit continued. The expected aid from the Crow people did not materialize. In October 1877, after a 1,100-mile chase, the US Army besieged the Nez Perce and their allies at Bear Paw in northern Montana. Many escaped to Canada or found their way back to the Umatilla and Nez Perce reservations. Others, exhausted from the ordeal, were forced to surrender.

The memory of the 1877 war lingered for many generations. The survivors mourned those who were lost and, as one Nez Perce historian puts it, "We mourn those lost, still. As time passes into the future, we slowly accept our great loss, strengthen our hearts, and continue with the living of today. Such is the teachings of our way. But we will never forget what happened here. To forgive... that is another matter."

The Land unites us with [our ancestors] across time, keeping our culture alive ... We live in the place our ancestors called home before the great pyramids of Egypt were built.

—Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee

Precious Homeland

You may feel that you know us because you have read our story already in the printed words of historians and other chroniclers of "life." You may see around you where the deep canyons of river and creek carvings created living spaces we no longer occupy. You may even taste and smell the air and feel the sun upon your face much as we had once done, so many years ago. Or perhaps you will enter a hall filled with dancers in their fine regalia and hear a prayer or two. Even so, you still may not truly understand us as a people.

The old people talked of these places. They talked of the beauty of "home" and of the abundance of food. They talked of landmarks and special places. They talked longingly of family and relatives of a misty past with whom they enjoyed living each day. And, finally, they talked of having to leave. They remembered starving and being cold. They remembered losing old ones and young ones ail along the way. And they remembered the deeper pain of loss—not simply of a precious homeland but of human beings they once knew and loved: "We left many of our people buried out there. We pray they will never more be disturbed."

Today, you may read and hear different forms of their expressions. In English. And you will miss the nuance of expression that comes from the heart of our ancient tongue. Our survivors and historians spoke "nimiputimpki," in the Nez Perce way. It is these stories that were handed down from generation to generation. It is the ancient tongue that truthfully relates out hearts and our truths.

One cannot truly say, in English, what we express in our language. There are many expressions that cannot be directly translated into the language of the "conquering peoples." No, you may not hear our truths as our people had once expressed them. And you may not understand our hearts as a consequence. Today, some are learning to speak that ancient tongue of our heart's expression: our ancestral language. Is it possible that we, too, might convey these histories in the old way, that our past may live in the consciousness of our young people's tomorrow, that they will not forget our origins so easily.

We, the descendents, live far apart from one another in today's world—not only in miles distant, but ideologically and spiritually. We live in a scattered way today. However, we are still the walwama of the Wallowa Valley. We are still the lamtama of the Salmon River country. We are still the kamnaha of the upper Clearwater country. We are still the palucpu and weyiletpu of the Snake River country. We are still the asotans of the lower Clearwater. We are still halalhutsut's pople of the treaty bands. And we are still the cupnitelu, "the ones who came out of the woods" (nun wisix ikuyn nimipu)

Though you can behold the wonder of this country, you will not fully embrace the great power and strength of a united Nez Perce people before that Treaty of 1855. However that may be. Mother Earth turns upon a newer day and time. Perhaps it will be the young ones who will create a healing place for all our people's future. As you travel through this beautiful country with an eye of wonder, remember us as we once were while greeting us as we are today. In some places we are also visitors, as are you. Remember this when you enter the Salmon and Snake River and the Wallowa Valley countries, that this was also our home . . . once.

—Albert Andrews Redstar

Chief Joseph band

Colville Confederated Tribes>

(click for larger map) |

Plan Your Visit

Nez Perce National Historical Park has visitor centers in Spalding, ID, and at Big Hole National Battlefield. Both offer information, films, exhibits, ranger-led programs, and bookstores.

Bear Paw Battlefield is 16 miles south of Chinook, MT. Information is available at t he Blaine County Museum in Chinook.

Accessibility

We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For

information, ask at a visitor center or check the park website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2018)

lilóynin nun ɂóykalo ɂetx heki'ca

Glad to see each and every one of you.

Far from our beautiful homeland, upon this quiet terrain of our Earth Mother, the spirits now forever bear silent witness to our people's painful and tragic encounter with "Manifest Destiny." This is a place of mourning, not just for memorializing a past, but as a place for letting go of what might have been. Nations consecrate other battlefields in memory of lives lost, so too, may each of us now consecrate this place on behalf of our ancestors' exhausted bid for freedom.

This is a sacred place of geographical memory in our hearts. We are taught to "turn ourselves around" in reverence and prayer upon entry into sacred space. This prayerful act keeps us ever mindful of the presence of our Creator as we reach out to the heart... to know that we are always truly "one". We pray that our blood and memory forever fuse our spiritual connection to our ancestry who once tread upon this ground. As you enter here, may you join us in our prayer by showing, in your own way, a respect for all those who have gone before us.

Bear Paw Battlefield is the site of the last battle of the four-month Nez Perce War of 1877. The battlefield is a part of Nez Perce National Historical Park and Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail.

You white people measure the Earth, and divide it. The Earth is part of my body, and I never gave up the Earth, I belong to the land out of which I came. The Earth is my mother.

—Chief Tulhuulhulsuit

Fort Lapwai, 1877We do not wish to interfere with your religion, but you must talk about practical things. Twenty times over you have repeated the Earth is your mother, and that chieftenship is from the Earth. Let us hear it no more, but come to business at once.

—General Oliver O. Howard

Fort Lapwai, 1877

Battle and Siege

It is September 29, 1877. The prairie skies hint of rain, snow and cold, hard wind. Our memories return to early summer at Tepahlewam near Tolo Lake, Idaho and the 800 men, women and children who began this journey. An ultimatum by the U.S. Government ordered us to move to a small reservation and give up our homeland. Five bands of Nez Perce, with some Cayuse, Palouse and other allies, reluctantly comply. After our young men retaliated for crimes against us, the army pursues us. To keep our freedom, we elude the military and leave our homeland. We feel the loss of nearly 100 relatives who died since June. Our camp is primitive, with crude lodges and lean-tos. It is a two-day ride to Canada, a place promising freedom.

In a surprise attack at dawn on September 30, the soldiers stampede our horses. Less than 100 warriors defend our families against the charge of Colonel Nelson A. Miles' 400 troops and 50 scouts. Our warriors stop the army attack with heavy loss to both sides. Fearing the loss of too many men, Miles changes tactics and lays siege to our camp. Our camp is exposed to enemy fire. We are forced to seek shelter in pits dug into the frozen ground. Soldiers and Indians lay dead all around. Snipers prevent us from retrieving and burying our dead. We have been surrounded for four days and bombarded with cannon shells. Thirty of our people died this week. Some have fled during the battle and others are considering attempts to escape into Canada. When asked by Miles to end the fighting, our remaining leaders are unsure if they should trust the army.

Choices

Choices are few and none are favorable. Can we continue the fight? The supply of soldiers is endless. Should we try to escape on foot under cover of darkness through the lands of traditional enemies? Not everyone can make this trip. Many are too weak. Who will care for the elders, children, and wounded? Will we be able to bury our dead? Will we be allowed to go home?

Chief Joseph

Chief Joseph explains: Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. [Tulhuulhulsuit] is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say, "Yes " or "No ". He who led the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are, perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead.

In late afternoon, we surrender our weapons. As to our destination, Miles tells Joseph: Which is the place that you love to stay in? I want you to tell me, as I have the power to remove these white people, and let you live there. Miles also promises: I will give half of them [weapons] back to you after awhile.

The Siege Ends

On October 5 Tom Hill, a Nez Perce warrior, describes the end of the siege: I said go back to the trenches, we will have to quit fighting. While I was talking... two Nez Perce Indian scouts [Capt. John & George Me-yop-kar-wit] ... had a white flag tied to their pole, they were coming across to see us. ... White Bull took up his gun and was going to kill both of these scouts. One Indian who is now dead told him to stop. I met these scouts and shook hands with them and told both of them not to be afraid; they would not be killed; and then they both shed tears and wept and of course we Indians came out of the trenches and shook hands with them. Joseph said "We will now quit fighting" ... Then they all came together and went across to Gen. Miles and Gen. Howard ... we all shook hands. Gen Howard said "Don't be afraid, you will not be hurt anymore". ... We stayed over with the troops, children and all. ... They thought we were a curiosity... he [Howard] did command the soldiers to keep away from them and they left us alone.

Escape to Canada

Nearly 150 of our people make their way to Canada. Among them is 12 year old Kulkulsta (Mark Arthur). As an adult he recalls: I ran with our horses... the bullets are everywhere; I cried to go to my mother in camp, but our people held me tight and wouldn't let me go. I went through bushes a long way; then I found some people and we went on together. Chief Joseph, our big men and my mother are not with us; we do not know if they are killed or prisoners; it was seven years before I saw my mother again.... We went to the Sioux camp in Canada. [They] were very good to us but it was very cold and there was very little food; sometimes there was just one rabbit for ten people.

Over several days, our people arrive in small groups at Sitting Bull's camp near Fort Walsh, Canada. The Sioux believe the battle rages far away on the Missouri River. More refugees arrive. Finally, the Sioux understand the battle is only two days south on a tributary of the Milk River. With our warriors beside them, a band of Sioux starts south. Just past the 'Medicine Line' (the Canadian border), they encounter 30 of our people led by Chief White Bird. Our people who remained on Snake Creek have surrendered their weapons to the U.S. Army. They will suffer if rescue is attempted. Most of the relief party returns north with the new refugees. A few continue on to the place of battle to properly bury the dead.

Living in Exile

With the promises broken by the military, 432 of our people are exiled to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) under the leadership of Joseph. Yellow Wolf remembers: We were not badly treated in captivity. We were free as long as we did not come towards Idaho and Wallowa. Only the climate killed many of us. All the newborn babies died, and many of the old people too. Everything so different from our old homes. No mountains, no springs, no clear running rivers... We called where we were held Eeikish Pah [Hot Place]. All the time, night and day, we suffered from the climate. For the first year, they kept us all where many got shaking sickness, chills, hot fever. We were always lonely for our old-time homes."

Wandering and Capture

Some of our people risk all to rejoin their families. Peo Peo Tholekt remembers: I felt very down-hearted as I drifted. The memory was strong — Wallowa — the home of my father. I shall now drift alone. Unfriended and without a home. No where to sleep in comfort, hungry every day, wandering as a chased coyote. Seeking for shelter and not found.... Naked, crying over my brothers and sisters when I left them corraled by the soldiers. They will all be killed! I did seek friends among tribes speaking a different language. I found the Sioux. I remembered the Sioux had always been an enemy to my tribe! But they proved friendly to me, keeping me for a year.

Tom Hill recounts: During the surrender we were ordered to go out in the prairie to look for Nez Perce. I obeyed the order and I left for good. After staying away for about one year I was recaptured. I was then taken to Indian Territory to [join] the Nez Perce there. I stayed seven years. Then I was returned with the Nez Perce to Idaho. Chief Joseph and a band with him elected to come to Nespelem [on] the Colville Reservation in Washington.

Today

Each generation of Nimiipuu descendants seeks healing for the grief, sorrow, and loss of family members and their homeland. The War of 1877 has far-reaching consequences. One result is the scattering of Nez Perce into Canada and across the United States (with principal enrollments on the Colville, Nez Perce, and Umatilla Indian Reservations). Schisms still exist, fractionalizing what was once a gentle balance among the many bands of Nimiipuu.

A young Nez Perce/Cayuse/Palouse boy takes off his coat, shoes, and socks on the battlefield. His puzzled mother asks what he is doing. He replies: To see how it feels. Those people who were here didn't have these things.

Make of this place and this history what you will. Convey to your children the sacred significance of this place for all time.

With humility, we pay homage to and echo our elders' prayer to return to our beautiful homeland far distant from this quiet place.

GUIDE TO NUMBERED STOPS ON TRAIL

C'aynnim 'Alikinwaaspa

Yellow Wolf remembers making camp on September 29, 1877: Next morning, not

early, the camp moved. We knew the distance to the Canadian line. But there was

no hurrying Looking Glass, leader since crossing the big river [Missouri]. About

noon the families came to where camp was to be made. The scouts knew and had

several buffalo killed at the campground. The name of the place is [C'Aynnim

'Alikinwaaspa — Place of the Manure Fire]. Only scarce brushwood, but

buffalo chips in plenty. With horses' feet sick [tender] and lots of

grass, the chiefs ordered, "We camp here until tomorrow forenoon."

1 Making Camp

Abundant game and fresh water offered by Snake Creek made this a good place to

camp and gather supplies before the final push to Canada. Lean Elk and Wottolen

expressed concern. Both experienced visions of attack. However, the fatigue of

the forced march and no sign of the military convinced the chiefs to order

camp.

The teepees destroyed at Big Hole left little else for protection. Huddled in crude lodges and wrapped in blankets the people camped, warmed by fire pits burning buffalo dung. The village was arranged in familiar patterns with families, bands and allies together.

2 Horses! Horses!

On the morning of September 30, Yellow Wolf recalls: Next morning, not too

early, while some were still eating breakfast, two [Nez Perce] scouts

came galloping from the south. As they drew near, they called loudly. Stampeding

buffaloes! Soldiers! Soldiers!

The young son of White Bird recalls the surprise: It was morning and we children were playing. We had hardwood sticks, throwing mud balls. I looked up and saw a spotted horse, a Cheyenne warrior, wearing a war bonnet, come to the bluff above me. He was closely followed by the troops. Some of the children ran back to the camps, some hurried to the gulch.

Horses were critical as Yellow Wolf recounts: Joseph's voice was above the noise as he called "Horses! Horses! Save the horses! Black Eagle recalls: I left going for the horses. I saw our horses not far away. The horses were wise to the shooting and all began to stampede. Within minutes hope faded as horses were scattered.

3 Nez Perce Camp Under Siege

Yellow Wolf reflects: Evening, and the battle grew less. Only occasional

shots. Soldiers guarding, sitting down, two and two. Soldiers all around the

camp so that none could escape. It was snowing. The wind was cold. About 450

men, women and children retreated to the north end of the camp. On the flats and

the sides of the coulees the ground became frozen as rain turned to snow and

temperatures dropped.

A Nez Perce woman recalls: We digged trenches with camas hooks and butcher knives. With pans we threw out the dirt. We could not do much cooking. Dried meat and some other grub would be handed around. It would be given to the children first. I was three days without food. Children cried with hunger and cold. In the small creek there was water, but we could get to it only at night.

Four more terrifying days remained. On October 4, according to Yellow Wolf: It was towards noon that a bursting shell struck and broke in a shelter pit, burying four women, a little boy, and a girl of about twelve snows. This girl and her grandmother were both killed. The other three women and the boy were rescued.

4 Point of Rocks

After scattering the horses, the Army and Cheyenne Scouts turned their attention

to fleeing Nez Perce and defenders at the north end of the camp. Among the

defenders were Tulhuulhulsuit and seven warriors. Caught between the 2nd Cavalry

and Scouts, the warriors became trapped at the base of the red, rocky outcrop.

In the open and unable to find a defensible position, Tulhuulhulsuit and five

others were killed. Eagle Necklace the Younger and Tamyahnin were wounded but

made it back to camp.

5 Rifle Pits

Ollikut, Lean Elk and other warriors met the soldiers as they advanced along

this bluff. The fighting was intense and made worse by low clouds and drizzle.

The Army was stopped, but the Nez Perce suffered serious losses as 26 died the

first day. On the west edge of the bluff, a marker identifies where Ollikut,

Joseph's brother, was killed. Across the coulee to the northeast Lean Elk was

mistaken for an enemy in the severe weather and killed by other Nez Perce. His

warning to Looking Glass had come true that neither would leave this place.

Nez Perce warriors prepared fortifications in the form of shallow rifle pits on the bluffs overlooking the camp and in the coulees leading into it. Yellow Wolf remembers October 2: It came morning, third sun of battle. The rifle shooting went on just like play. But soon Chief Looking Glass was killed. Some warriors in [this] pit with him saw at a distance a horseback Indian. One pointed and called to Looking Glass "Look! A Sioux!" Looking Glass stepped quickly from the pit. Stood on the bluff unprotected. A bullet struck his left forehead and he fell back dead. Looking Glass was hopeful help had come from the camp of Sitting Bull in Canada.

6 Negotiations or Deception?

Under a U.S. flag of truce on the morning of October 1, Miles and Joseph met.

The precise meeting location is unknown. At the end of the meeting, Joseph

turned to leave. He was called back by Miles and was placed in chains.

Shortly after Joseph's capture, Lieutenant Lovell Jerome was captured while on reconnaissance. By his account he was given food, blanket, shelter and allowed to move freely about the Nez Perce camp while retaining his pistol.

On October 2nd a prisioner exchange was arranged under the watchful gun sights of soldiers and warriors. The siege continued without negotiations until October 5.

7 Initial Assault

Company K of the 7th U.S. Cavalry charged and outpaced the remainder of Miles'

command along this bluff. They expected little resistance. Racing northward with

the 7th Captain Myles Moylan recalls: After crossing the divide which

separated us from the Indians village, the battalion formed a line about

1½ miles from the village, Company K on the right, Company D in the

center, and Company A on the left. During the movement to the front line,

Company K struck the Indians first and was repulsed [after being]

severely handled by the Indians. Somewhere near the trail as Lieutenant

Henry Romeyn explains: Captain [Owen] Hale and Lieutenant

[Jonathan] W. Biddle [of Comp. K] were killed at the first.

Numerous officers and enlisted men were wounded. The element of surprise was

lost.

8 Code of Honor

On the left coulee slope, Moylan recalls: Capt [Edward F.] Godfrey had

his horse killed from under him. The fall stunned him. Trumpter Thomas Herwood

rode between Godfrey and the Indians. In this gallant attempt to save his

officer, Trumpter Herwood was wounded.

Before you, in the gully draining to Snake Creek, soldiers lay dead or wounded as the evening fell. Romeyn remembers: Those who fell into the hands of the hostiles were not molested otherwise than to be stripped of arms and ammunition. They [Nez Perce] even gave some of the wounded water after nightfall when it could be done safely. Another account recalls a warrior giving a blanket to a wounded soldier.

9 The Army Regroups

Much of the initial fighting occurred along this narrow bluff overlooking the

Nez Perce Camp. Romeyn recounts: At the south end of the campground there was

a perpendicular bluff that afforded excellent cover. This was instantly occupied

by the Nez Perces who, withholding fire until the 7th [Company A & D]

were within two hundred yards, then delivered it with murderous effect.

Wherever the Indians heard a voice raised in command there they at once directed

their fire.

After retreating, Miles ordered the cavalry to dismount and reinforce Company K. Fire was directed toward the bluff on the west side of the coulee. The Nez Perce held their position of advantage. The 5th Infantry came up and was halted at the crest. Here it was met by a hot fire from the coulee and men and horses began to drop before they could dismount. The Hotchkiss gun was brought up [near this location] and was soon driven from the position with severe loss to its gunners. Only hand to hand combat with units of the U.S. 5th Infantry forced the Nez Perce to yield the high ground. Romeyn continued: By three o 'clock it was evident that the attack must become a siege.

10 Soldier Grave Site

A temporary field hospital and command post were located here as described by

Romeyn: A small piece of ground directly in the rear of the steep bluff

alluded to was sheltered from the enemy's fire, and the wounded who could walk

or crawl were gathered for attention by the Surgeons. Two fallen soldiers

were returned to their hometowns for burial. Twenty-one soldiers were buried in

a mass grave. From 1877 to 1903 local residents maintained the gravesite. The

remains of the soldiers were removed to Fort Assiniboine in 1903. Then, in 1912,

they were relocated to Custer National Cemetery at Little Bighorn Battlefield

National Monument. The long depression is the only evidence of the mass

grave.

11 Relinquishing the Rifle

On the morning of October 5, the two remaining hereditary leaders, White Bird

and Joseph, met two 'Treaty Nez Perce' to discuss terms of "quitting the fight".

White Bird mistrusts the Army's promises, refuses to surrender, and with 30

others escapes to Canada that night. Joseph declares to the Nez Perce Camp that

his decision to end the fighting is to save his people. At 2:00 PM, as he hands

over his rifle to Miles, he states briefly and simply, "From where the sun

now stands, I will fight no more, forever."

Visiting Bear Paw Battlefield

Bear Paw Battlefield is 16 miles south of Chinook, Montana on Route 240. A self-guided trail, picnic tables, and primitive toilets are available. The office in Chinook is on the SW corner of US 2 and Indiana Street in the Chamber of Commerce Visitor Center.

Bear Paw Battlefield

P O Box 26

Chinook, MT 59523

The Blaine County Museum, the interim visitor center, is a good place to begin your visit. The multimedia presentation "40 Miles From Freedom" describes the Battle of Bear Paw. The museum also has exhibits on local history and paleontology. Contact the museum for hours.

Blaine County Museum

501 Indiana Street

Chinook, MT 59523

Bear Paw Battlefield is the final stop on the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail. The 1,170 mile trail starts in Joseph, Oregon, following the path of non-treaty Nez Perce during the War of 1877. The trail passes through federal, tribal, state and private property.

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail

USDA-Forest Service

Region 1, WRHP

P O Box 7669

Missoula, MT 59807

Camping, hunting, trapping, collecting or digging are prohibited.

Any person who, without an official permit, injures, destroys, excavates or removes any historic or prehistoric ruin, artifact, object of antiquity, or other cultural or natural resource on public lands of the United States of America is subject to arrest and penalty of law.

Stay on the designated trail. Do not remove offerings or artifacts. The trail is designed for foot travel only. Please no pets, bicycles, or motorized vehicles on the trail.

This is sacred ground for all who fought here. It remains today a burial ground to the Nez Perce people who lost their lives while seeking freedom.

Source: NPS Brochure (undated)

|

Establishment Nez Perce National Historical Park — May 15, 1965 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A History, Nez Perce Campaign 1877: Part I (Merrill D. Beal, 1960)

A History, Nez Perce Campaign 1877: Part II (Merrill D. Beal, 1960)

Administrative History, Nez Perce National Historical Park (HTML edition) (Ted Catton, September 1996)

A Master Plan for Nez Perce National Historical Park (HTML edition) (June 1968)

And It Is Still That Way...Educational Programs at Nez Perce National Historical Park (undated)

And It Is Still That Way: An Educator's Guide (undated)

Bird Inventories of Big Hole National Battlefield, Nez Perce National Historical Park, and Whitman Mission National Historic Site 2005 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/UCBN/NRR-2009/125 (Rita Dixon and Lisa K. Garrett, August 2009)

Camas Monitoring at Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield

Camas Lily Monitoring Protocol Narrative NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/UCBN/NRR-2007/011 (Thomas J. Rodhouse, Mark V. Wilson, Kathryn M. Irvine, R. Kirk Steinhorst, Gordon H. Dicus, Lisa K. Garrett and Jason W. Lyon, version 1.0, October 2007)

Camas Monitoring at Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield: 2008 Annual Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/UCBN/NRTR-2008/133 (Thomas J. Rodhouse and Lisa K. Garrett, November 2008)

Camas Monitoring at Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield: 2009 Annual Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/UCBN/NRTR-2009/265 (Thomas J. Rodhouse and Jannis L. Jocius, October 2009)

Camas Monitoring at Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield: 2010 Annual Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/UCBN/NRTR-2011/430 (Thomas J. Rodhouse and Jannis L. Jocius, February 2011)

Camas Monitoring at Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield: 2011 Annual Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/UCBN/NRTR-2013/804 (Thomas J. Rodhouse and Devin S. Stucki, October 2013)

Camas Monitoring at Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield: 2012 Annual Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/UCBN/NRTR-2013/809 (Thomas J. Rodhouse and Devin S. Stucki, October 2013)

Camas Monitoring at Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield: 2013 Annual Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/UCBN/NRTR-2013/816 (Thomas J. Rodhouse and Devin S. Stucki, November 2013)

Camas Monitoring in Nez Perce National Historical Park's Weippe Prairie: 2014 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/UCBN/NRDS-2017/1079 (Devin Stucki and Thomas J. Rodhouse, January 2017)

Camas Monitoring in Nez Perce National Historical Park's Weippe Prairie: 2015 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/UCBN/NRDS-2017/1078 (Devin Stucki and Thomas J. Rodhouse, January 2017)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: East Kamiah/Heart of the Monster, Nez Perce National Historical Park (1994, rev. 2002)

Draft General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Nez Pere National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield Draft (October 1996)

Feasibility Report: Nez Perce Country National Historic Sites, Idaho (Daniel F. Burroughs, Alfred C. Kuehl, John A. Hussey and Erwin N. Thompson, October 1963, corrected June 1964)

Forlorn Hope: A Study of the Battle of White Bird Canyon Idaho and the Beginning of the Nez Perce Indian War (John Dishon McDermott, June 1, 1968)

Foundation Document, Nez Perce National Historical Park, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington (April 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Nez Perce National Historical Park, Idaho-Montana-Oregon-Washington (January 2017)

General Management Plan, Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield (September 1997)

Historic Resource Study: Fort Lapwai, Nez Perce National Historical Park, Idaho (Erwin N. Thompson, July 1973)

Historic Structure Report, Spalding Area: Nez Perce National Historical Park, Idaho Architectural Data (David G. Henderson, January 1974)

Historical Trauma: A Case Study on the Phenomenon Within the Nez Perce (Sarah Nichole Parker, Master's Thesis University of Montana, Summer 2007)

Land Protection Plan, Nez Perce National Historical Park and Big Hole National Battlefield (1999)

Long-Range Interpretative Plan, Nez Perce National Historical Park (undated)

Mammal and Herpetological Inventories, Nez Perce National Historical Park (Crystal Ann Stobl, Lisa K. Garrett and Tom Rodhouse, November 2003)

McLoughlin and Old Oregon: A Chronicle (Eva Emery Dye, 1913)

Museum Management Plan, Nez Perce National Historical Park (Robert Applegate, Lisbit Bailey, Kent Bush, Bob Chenoweth, H. Dale Durham, Diane Nicholson and Nakia Williamson, August 2005)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Lenore Site (Earl H. Swanson, 1974)

Lolo Trail (Merle W. Wells, September 13, 1988)

Pierce Courthouse (Merle Wells, February 24 1972)

Saint Joseph's Mission (Slickpoo) - Site 9 (Laurin C. Huffman and Jack Williams, November 1973)

Tolo Lake (Suzanne Julin and Suzi Pengilly, May 9, 2010)

Weippe Prairie (Blanche H. Schroer, William Everhart and Charles Snell, 1976)

White Bird Battlefield - Site 13 (Jack R. Williams and Laurin C. Huffman II, March 15, 1973)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Big Hole and Bear Paw National Battlefields of the Nez Perce National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/UCBN/NRR-2011/471 (Mark V. Corrao and John Erixson, December 2011)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Nez Perce National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/UCBN/NRR-2010/333 (John Erixson, Jack Bell and Dustin Hinson, March 2010)

Newsletter (Partners and Friends): Vol. 1 No. 1 • Vol. 1 No. 2 • Vol. 2 No. 1 • Vol. 2 No. 2 • Vol. 2 No. 3 • Summer 2005 • Fall 2005 • Summer 2006

Nez Perce Country: A Handbook for Nez Perce National Historical Park, Idaho (1983)

Nez Perce Cradleboards (2005)

Nez Perce Ethnobotany: A Synthetic Review (Joy Mastrogiuseppe, November 2000)

Nez Perce National Historical Park: Additions Study (1990)

Nez Perce National Historical Park Archaeological Excavations, 1979-1980 University of Idaho Anthropological Research Manuscript Series No. 70 (Part 1: Karl Gurcke, Part II: Caroline D. Carley, 1981)

Nez Perce Summer, 1877 - The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis (Jerome A. Greene, 2000, ©Montana Historical Society Press)

Paleontological Resource Inventory and Monitoring, Upper Columbia Basin Network NPS TIC# D-259 (Jason P. Kenworthy, Vincent L. Santucci, Michaleen McNerny and Kathryn Snell, August 2005)

Park Newspaper: 2003-4 • 2004 • 2005 • 2006 • 2007 • 2008 • 2009 • 2012

Reconnaissance Geohydrology of Proposed Park Sites in Nez Perce National Historical Park Area, Idaho (Ralph F. Norvitch, February 1967)

"Ruining" the Rivers in the Snake Country: The Hudson's Bay Company's Fur Desert Policy (Jennifer Ott, extract from Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 104 No. 2, 2003)

The Flight of the Nez Perce ...through the Bitterroot Valley — 1877 Auto Tour (U.S. Forest Service, 1995)

The Flight of the Nez Perce ...through the Big Hole, Horse Prairie and Lehmi Valleys — 1877 Auto Tour (U.S. Forest Service, 1997)

The Nez Perce Indians in Canada, 1877 and After (Jerome A. Greene, December 2007)

The Nez Perce War of 1877 (Richard A. Cook, extract from The Denver Westerners Roundup, Vol. 37 No. 3, March-April 1981; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

Upper Columbia Basin Network Integrated Water Quality Annual Report 2008: Nez Perce National Historical Park and Whitman Mission National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/UCBN/NRTR—2009/214 (Eric N. Starkey, May 2009)

Vegetation Inventory Project, Nez Perce National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/UCBN/NRR-2012/531 (John A. Erixson and Dan Cogan, June 2012)

Weippe Prairie Camas Lily Pilot Sampling Project: Summary of Findings (Tom Rodhouse, July 28, 2005)

Why Should We Have to Buy Our Own Things Back? The Struggler over the Spalding-Allen Collection (©Trevor James Bond, PhD Thesis Washington State University, May 2017)

nepe/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025