|

OREGON'S HIGHWAY PARK SYSTEM: 1921-1989 An Administrative History |

|

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW (continued)

BUILDING THE LAND BANK: THE S. H. BOARDMAN ERA

The Boardman era of State Parks administration was characterized by rapid growth in numbers of parks with a gradual buildup of staff. Much emphasis was placed on protection of park lands rather than development. The operation was largely orchestrated by Sam Boardman himself, a single-minded leader with minimal staff.

A hard-working and dedicated person, Mr. Boardman, who became State Parks engineer at the age of 55, traveled constantly over the state contacting people about the acquisition of new lands. At first he followed the charge to obtain forest lands along state highways. But he soon expanded to the acquisition of state park units, particularly along the Oregon coast. As early as 1929, an effort was made to acquire lands along the Curry County coastline, between Pistol River and Brookings, which today are a part of Samuel H. Boardman State Park.

Boardman recognized the unusual relationship of the Oregon coast with respect to the nearby highway, and while staying within a reasonable distance of the shoreline, he sought to control as much of the coastline as possible. This served the needs of the Highway Commission while providing for easier public access to the ocean. Though he had a broad vision for large area protection such as at Humbug Mountain, Umpqua Lighthouse, Honeyman, Cape Lookout, Short Sand Beach (now Oswald West) and Ecola parks, in many of the areas such as at Devil's Elbow and numerous coastal waysides only a major access or feature was acquired. The coming expansion of coastal travel and range of requirements for public use were not entirely foreseen in the 1930s. The staff was not increased to plan future development.

There were a number of reasons for the conservative approach to development of the park system at the time. The Great Depression was just beginning as Boardman took over, and expenditures and programs were curtailed. His own salary was reduced in 1932 and 1933. Since the state parks had not been made a public issue but were under Highway Commission control, the development of a state park system had few champions. The prevailing view was that land should be acquired before it was lost to the public and betterment would take place later.

The Parks engineer's method of operation was geared to constant travel and personal contact with prospective grantors, highway commissioners and other key people helpful to the parks program. He had a remarkable ability to influence people toward gifts or sale of land. He spent limited time on personnel or other administrative concerns, preferring to leave such matters in the hands of the Salem office staff. In the 1940s, it was Gertrude M. Chamberlin, his capable secretary, who managed the office, and Miss Chamberlin continued her important role in administrative support under Boardman's successors.

Boardman's interest, of course, covered all of Oregon, though the coast contains the largest number of his land acquisitions. Along the Columbia River, he early recognized the need for protection of park land on both sides of the river. Some 35 miles east of Vancouver on the Washington side of the Columbia is Beacon Rock, a large monolith named by Lewis and Clark in 1805 and long a guide to travelers on the river. The rock was privately owned, and though there was occasional consideration of its use for quarrying, the owners preferred to see it protected as a park. It had been offered to the state of Washington, but the opportunity for public acquisition was declined.

Learning of the matter, Boardman contacted key people in Vancouver as well as the owner and found that Beacon Rock could be offered to the State of Oregon if the state agreed to maintain it as a park. Although Highway Commission Chairman H. B. Van Duzer had his doubts about the matter, he agreed to allow information on the proposed gift to be given to the Portland papers. The Oregonian reported editorially that Beacon Rock in the Columbia River Gorge had been acquired by its owner to save it from being quarried. The owner built a trail to the top, making it worth preservation as a scenic wonder. A gift offer having been made to the state of Washington and refused, it was now to be offered to the state of Oregon as a state park.

The response in Washington was quick and critical of Oregon for overstepping its boundaries. After some negotiating, Beacon Rock became a Washington State Park, as Mr. Boardman had hoped it might all along. [1] The objective had been protection, and the incident illustrates Boardman's skill in making things happen.

Rather than making a general survey of potential parks in Oregon as a whole, Sam Boardman concentrated his effort on the Oregon coast, the Columbia Gorge, roadside forest strips and other areas of special interest. Parks were only modestly developed in order to retain their natural beauty as much as possible. [2]

While most of the park areas were situated along or in close proximity to the state highways, a number of areas extended well beyond the highways or required special access roads. Saddle Mountain State Park (2,911 acres) near Seaside, for several years the largest Oregon state park, is located eight miles off the Sunset Highway.

The Cove Palisades State Park in Jefferson County (4,129 acres), an outstanding geologic area now containing a large reservoir at the confluence of the Crooked, Deschutes and Metolius rivers, is situated on secondary roads 15 miles southwest of Madras. In 1937, the Resettlement Administration in the U. S. Department of Agriculture purchased land on the Crooked River, part of which was developed as a picnic area. For lack of maintenance funds, it was offered to the state of Oregon as a park. Boardman was impressed with the scenic and geologic splendor of the area. Obtaining commission approval, the State Parks staff acquired lands from the federal government, Jefferson County, State Land Board and various public owners, expanding the tract to 4,533 acres by 1947. [3] Minimal day use improvement was made in the park up to 1951.

Acquisition of Golden and Silver Falls State Park, located on a state secondary road 24 miles east of Coos Bay, was more complex. The park contains two spectacular waterfalls in a fine forest of Douglas fir. The Waterford Lumber Company offered it to the state in exchange for road improvements. At first the park's acquisition was opposed by highway engineers because of its distance from the regular highway system and the cost involved in improving the road. Parks should be on the road system. That was the policy. Ultimately, the state made the road a secondary highway and the Highway Commission provided funds ($10,000) to make the road suitable for logging trucks. The area acquired by gift from the Waterford Lumber Company in 1936 was enlarged by acquisitions from Coos County in 1938 and 1955.

During the Depression years (1929-1941) money was in short supply for parks, especially for development. At this time the federal government undertook many relief programs to put people to work. Some of these were most helpful to park conservation and development. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), under the technical supervision of the National Park Service, carried on State Park Emergency Conservation Work (ECW). In Oregon the first two camps were established in October, 1933, near Gold Beach in Curry County and at Benson Park east of Portland on the Columbia River. [4] Over the years, until the close-down in 1942 with the entry of the United States into the Second World War, improvements were carried out in 45 state parks.

Though Sam Boardman initially welcomed the help, and obtained the added title of "Oregon Procurement Officer" from the National Park Service, he was uneasy about the number of technicians and the planning procedures. In a letter to his superior, State Highway Engineer R. H. Baldock, he stated, "steadfastly should we stand in the retention of the nativeness of our State Parks. Development should be held to the very minimum. There is nothing more beautiful in all the world than the verdure of our State Parks as the Great Architect designed them. When man's hand at its best touches them, desecration takes place. Pressure will be brought to bear to open them up for overnight camping -- when that is done grass will turn to the dust of earth, bush and foliage will wither and stunted stumps will remain..." [5]

Pressure for overnight camping was to build to the end of Boardman's tenure in 1950, but in the meantime he constantly complained to the National Park Service regional office in San Francisco about the plethora of plans and the number of landscape architects needed to design basic park facilities. [6] He also concerned himself with the consistency of road design and hoped to retain roadside beauty. [7]

The contribution of the Depression era work relief programs was valuable. Under President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, adequate public use facilities were provided for many state parks which otherwise would have remained undeveloped or underdeveloped. The Civilian Conservation Corps improvements at Jessie M. Honeyman Memorial State Park, south of Florence on the Oregon Coast Highway, remain today substantially as designed, a nationally recognized example of public park development pleasingly integrated with the natural setting.

There were other federal programs which benefitted the state parks. At Silver Falls State Park in the foothills of the Cascades east of Salem, in addition to major improvements by the CCC, work was done by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). This included design and construction of myrtlewood furniture at the Silver Falls Lodge, as well as landscaping in the parking area. [8] The major federal project at Silver Falls involved the Recreation Demonstration Area that was set up in 1934 under the direction of the Emergency Relief Administration, the National Park Service and WPA. The project area adjoined the original Silver Creek Falls State Park. Its purpose was to develop youth camps for city children on logged-over tracts and marginal agricultural land. The camps were developed after the government purchased the land. In 1948 and 1949, 5,989 acres were transferred to the state of Oregon for park purposes.

As a part of the ECW effort in Oregon, the National Park Service prepared development plans for outstanding coastal parks such as Ecola, Short Sand Beach (now Oswald West) and Cape Lookout. For the latter area, an extensive study was made of the cape by National Park Service biologist Lowell Sumner. [9] Boardman had long desired to keep this park as an undeveloped natural area, and it so remained until 1951.

Another special interest area was the John Day Fossil Beds region of central Oregon located in the basin of the John Day River. Here, Thomas Condon and other early paleontologists had made important discoveries of prehistoric life forms, and there was much interest in protecting the locality under State Parks jurisdiction. The area was comprised of several widely dispersed tracts, including the spectacular Painted Hills. Park areas were designated, but development and use were limited. Though he seemed to favor the John Day Fossil Beds park project as proposed by J. C. Merriam and others, Boardman was concerned about the costs involved in acquisition, development and management of such as area. [10]

Public use of state parks was limited generally at first by the condition of roads, but park visits grew steadily with the improvement of the highway system, especially on the Oregon coast. Figures on the number of persons who made use of the state parks system in the years before the Second World War were reported as follows: [11]

| Total | Coast Parks | |

| 1938 | 1,407,429 | 942,345 |

| 1939 | 1,715,357 | 1,215,846 |

| 1940 | 2,070,238 | 1,521,003 |

The coastal parks accounted for 70 percent or more of state park use.

The early link between highways and state parks frequently was advantageous to the Highway Commission. State Park lands provided convenient gravel stock pile sites and quarry sites for road building and rights-of-way for locating alignments. By the same token, Parks Engineer Samuel Boardman used the administrative connection to achieve his own goals of scenic conservation and roadside beautification. For example, he is known to have negotiated with State Highway Engineer R. H. Baldock for a change in alignment of the Oregon Coast Highway (U. S. 101) south of Arch Cape to conserve the forested area in Oswald West State Park. [12]

Because of the prolonged economic depression of the 1930s, the state was fortunate that its Parks head possessed the ability to attract gifts of funds and park land. Among those whose support was enlisted were: Rodney Glisan, Florence Minott, Caroline and Louise Flanders at Ecola State Park; Louis W. Hill Family Foundation at Cape Lookout State Park; L. J. Simpson family at Cape Arago State Park; Menasha Woodenware Company at Umpqua Lighthouse State Park; Borax Consolidated, Ltd. of London, England, at S. H. Boardman State Park; and the E. S. Collins family at Oswald West State Park. [13] In most cases, the early gifts provided a nucleus to which land acquisitions and gifts from county, state and federal agencies were added over the years to round out park holdings.

Organizations also aided the early park efforts. The Oregon Roadside Council, particularly in the person of the president, Jessie M. Honeyman, was supportive of the protection of roadside trees and the elimination of highway billboards. Save-the-Myrtlewoods was helpful in obtaining groves of Oregon myrtle (Umbellularia californica) and related park lands in southwest Oregon. The Recreational and Natural Resources Committee of the Portland Chamber of Commerce was sympathetic with Boardman's efforts and was instrumental in publishing as a separate booklet the articles on parks that, following his death, initially appeared in the Oregon Historical Society's quarterly journal under the title "Oregon State Park System: A Brief History."

While there were some state level groups formed to promote state park programs, none seems to have had the necessary support of the State Highway Commission. One of these was Governor Julius Meier's State Parks Advisory Commission, appointed May 17, 1933. The Parks Advisory Commission outlined its views on parks and roadside forest strips to the Highway Commission on June 27, 1933, after which there is no record of further meetings. [14] Another was the Oregon State Board of Higher Education Advisory Committee on State Parks, created in 1942. While this committee was concerned with many projects, an initial item was the creation of a parkway in the John Day region to be maintained by the Oregon State Highway Commission. The Education Advisory Committee was interested also in generating public information about the Columbia River Gorge and the Oregon coast as well as Crater Lake National Park. [15] Ideas on the John Day country were communicated to the Highway Commission, but were not taken seriously. Apparently, with the death of some of its organizers and post-war changes, the committee ceased to exist.

A federally sponsored commission, the Pacific Northwest Regional Planning Commission was composed of government representatives and planning leaders from northwest states. In 1934, it initiated a study of the recreational values in the Columbia River Gorge. Its report, published in 1937, made recommendations concerning roads, parks, and scenic resources. This study was far-seeing in its concept of freeway development and roadside parks. It provided guidelines and a base for later work of the Columbia River Gorge Commission. [16]

In 1936, a large area, some 30,000 acres along the Curry County coast, was proposed as a National Recreation Area. The general vicinity of this tract was between Pistol River and Brookings and was to include land from the ocean shore to the old Coast Highway at Carpenterville. The National Park Service made a study of the locality. Sam Boardman took visitors to see it and wrote enthusiastic letters to the Secretary of the Interior and others on its behalf. In May 1940, Senator Charles L. McNary introduced a bill in Congress for its creation, but the Bureau of the Budget eliminated federal acquisition funds. Although there was local support for the recreation area initially, opposition grew when federal funds were negated and use of highway monies for acquisition was not approved. Moreover, area stockmen did not want to lose their grazing land. The National Recreation Area project died in 1940. [17] Today, much of Samuel H. Boardman State Park includes coastal frontage of the proposed National Recreation Area. Primarily, this was acquired with right-of-way between 1947 and 1950 for the relocation of the Oregon Coast Highway.

The State Parks organization in Oregon was very small in the Boardman years, with all policy matters emanating from the Parks superintendent. In the 1930s there were three people in the Salem office and some six caretakers in charge of field areas. After the Second World War, the staff grew substantially. In 1949, there were 16 in the central office, 43 park caretakers and 21 laborers. Boardman issued generalized instructions to the caretakers on park management, stressing in order of priority: cleanliness, maintenance of latrines, friendly relations with park patrons, preservation of wildlife, restriction of dogs, maintenance of naturalness in preference to development, maintenance of all buildings and facilities, keeping park signs erect and painted, and taking proper safety precautions. [18]

The post-war era saw a great increase in the number of park visitors and in the complexity of park administration. In 1949, the state was divided into five park districts, each the responsibility of a supervisor. The landscape activities of the Oregon State Highway system were for a time the responsibility of the State Parks superintendent. With the rise in park use there was a demand for more facilities, especially camping areas. Though Boardman did not approve of camping, he finally allowed the planning of camping areas at Silver Falls and Wallowa Lake. As he approached retirement, he expressed his park philosophy to the caretakers:

A personal note is interjected to you as individuals. It will soon be 20 years that I have been gathering parks and waysides for the State of Oregon. Time has about run thru [sic] my course, and another 20 years will not be for me to fulfill. Thru [sic] the years, I have gathered unto the state, creations of the great Architect. Guardedly, I have kept these creations as they were designed. When man enters the field of naturalness, the artificial enters. Remember you never can improve on the design of your Maker in the creation of His pattern. Your hand can conserve what I have builded thru the years. In this preservation you will fulfill a creative tenet of the individual ordained by your Maker. In so doing, you will be director in keeping the recreational kingdom that has been a part of me thru the years. The dignity of man is formulated thru the unseen teachings of a creative world about him. Keep these teachings that you may not grow less in stature. [19]

Park visitation was estimated at 2,856,949 persons in 1949. As of January 1, 1950, there were 161 units in the Oregon State Parks system, making a total of approximately 60,000 acres. [20]

In the 21 years of his tenure, Mr. Boardman had expanded the park system, which had but 4,070 acres in 46 units in 1927. Oregon State Parks benefitted from his ability, devotion and personal enthusiasm for park preservation. Now it was time to expand park development for public use. To do this, Chester H. Armstrong, assistant State Parks superintendent, took over in the summer of 1950.

1. Samuel H. Boardman. 1958. Oregon State Park System. Oregon Historical Society. Portland, Oregon. p. 23-28. Reprint from the Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 3. September 1954.

2. Samuel H. Boardman. 1936. "State Parks in Oregon," The Oregon Blue Book 1935-1936. Salem: State Printing Department. 131-2.

3. Boardman. 1956. op. cit., p. 49-54.

4. Chester H. Armstrong. 1965. History of the Oregon State Parks 1917-1963. Salem: Oregon State Highway Department, 24.

5. Boardman to R. H. Baldock, June 10, 1937. OSPF.

6. Boardman to Lawrence C. Merriam. December 30, 1934. OSPF.

7. Boardman to Mark H. Astrup. December 21, 1936. OSPF.

8. Armstrong, op. cit., p. 27-28.

9. B. Lowell Sumner. 1941. Special Report on Cape Lookout State Park and Netarts Bay. Oregon. 41-page ms, OSPF.

10. Boardman to H. F. Cabell. October 21, 1942. OSPF.

11. Oregon Blue Book 1941-1942. Salem: State Printing Department, 176.

12. Boardman to Baldock. June 10, 1933. OSPF.

14. Armstrong. op. cit., p. 34.

15. Ibid., p. 34-36; John C. Merriam to Lawrence C. Merriam, June 19, 1942. Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

16. Pacific Northwest Regional Planning Commission. Columbia Gorge Committee. 1937. Columbia Gorge Conservation.

17. Armstrong, op. cit., p. 32-33; Boardman to Harold L. Ickes. April 4, 1939. Oregon State Archives. Salem.

18. Boardman to all caretakers. February 15, 1949. OSPF.

20. Narrative Report, Oregon State Parks for 1949, to U. S. National Park Service. OSPF.

|

| Fig. 3. Louis Boes was one of many Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees from Ohio in Company 572 assigned to the camp at Humbug Mountain on the southern Oregon coast, south of Port Orford. SP6 was one of 17 CCC camps established in Oregon state parks to carry out federally-sponsored emergency relief work during the Depression era. The site of SP6 eventually was absorbed in a new alignment of the Coast Highway. |

|

| Fig. 4. Left: Bunkhouse interior. Right: SP6 camp buildings as viewed from the west flank of Humbug Mountain. 1936. Courtesy of Louis Boes, Tiffin, Ohio. |

|

| Fig. 5. Civilian Conservation Corps units and State Parks employees worked from spike camps to complete work in large undeveloped parks. Here, workers encamped at Jackson Creek in Cape Lookout State Park, on the northern Oregon coast, were engaged in constructing a five-mile hiking path through rain forest to the tip of Cape Lookout. 1939. Glen O. Stevenson Photo, Oregon State Parks. |

|

| Fig. 6. Picnickers enjoy day-use facilities at Devil's Punchbowl State Park on the central Oregon coast. Fence rails and picnic table assemblies of peeled logs were crafted by CCC workers to harmonize with the surroundings in accordance with National Park Service guidelines. 1940s. Ralph Gifford Photo #490, Oregon State Highway Department |

|

| Fig. 7. One of the outstanding collaborative developments involving Oregon State Parks, the National Park Service and Civilian Conservation Corps was the Bathhouse on Cleawox Lake in Jessie M. Honeyman Memorial State Park on the central Oregon coast. Seen behind the swimming dock, the stone terrace and rustic bathhouse-concession building represent the National Park ideal of integrating recreational features with the natural setting through the use of native materials and low, ground-hugging building mass. Such construction projects required intensive hand labor and resulted in high quality, enduring facilities. 1940s. Ralph Gifford Photo #1291, Oregon State Highway Department |

|

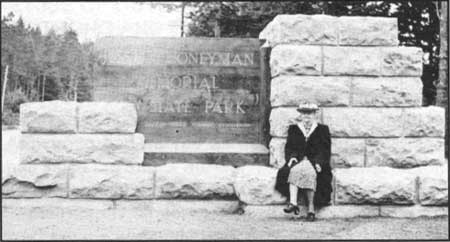

| Fig. 8. Seated on the rock-faced pylon that was located on the Oregon Coast Highway south of Florence to mark the entrance to the park named in her honor, Jessie Millar Honeyman participates in dedication-day observances in 1941 at the age of 89. Mrs. Honeyman, then current president of the Oregon Roadside Council, was for many years a leading advocate of roadside beautification, parks and scenic conservation. Jessie M. Honeyman Memorial State Park illustrated the importance of good roads to opening new areas to recreation. Tracts making up the popular coastal park surrounding two fresh-water lakes were under development by the CCC for a period of five years. July 12, 1941. Oregon Journal Photo, Oregon Historical Society, #cn 011424. |

|

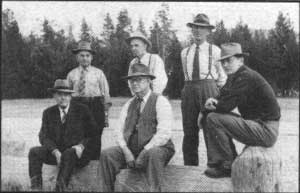

| Fig. 9. Locating distinctive areas for addition to the growing State Parks system required constant travel and conferring with park advocates, prospective donors and government officials. Here, State Parks Superintendent Samuel Boardman (seated center) pauses at Diamond Lake in the early 1940s during a tour with John C. Merriam, president emeritus OT the Carnegie Institution of Washington (seated left). Dr. Merriam, whose academic discipline was paleontology, was a member of the short-lived Oregon State Board of Higher Education Advisory Committee on State Parks, which urged consideration of educational values in building the parks framework. Standing, left to right, are Douglas County Commissioners, D. N. Busenbark, judge; J. Ross Hutchinson (see Hutchinson State Wayside) and H. B. Roadman. The driver is unidentified. c. 1943. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Lawrence C. Merriam, Jr, Corvallis, Oregon. |

|

| Fig. 10. The Oregon State Highway Commission assessed highways and parks during periodic inspection trips. On August 24, 1943, the commission and its traveling party was photographed at Vista House scenic overlook atop Crown Point on the old Columbia River Highway. From left: H. B. Glaisyer, commission secretary; Arthur W. Schaupp, Highway commissioner; H. G. Smith, construction engineer; Alex Cornett; R. H. Baldock, Highway engineer; Merle R. Chessman, Highway commissioner; Samuel Boardman, Parks superintendent; Thomas H. Banfield, Highway Commission chairman; and Mr. Kelly. 1943. Ralph Gifford Photo, Oregon State Highway Department. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

overview1.htm

Last Updated: 06-Aug-2008