|

OREGON'S HIGHWAY PARK SYSTEM: 1921-1989 An Administrative History |

|

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW (continued)

THE RISE OF OUTDOOR RECREATION: C. H. ARMSTRONG AND THE POST-WAR DECADE

With the appointment of Chester H. Armstrong as State Parks superintendent commencing July 1, 1950, the administrative emphasis shifted from acquisition of new park units to development for public use. Armstrong had served as assistant superintendent under Boardman since the end of the war, and before that he had supervised park betterment work while stationed at Pendleton as district maintenance superintendent for the State Highway Department. A native of Oregon, he had attended Willamette University and Oregon State College. He had worked briefly for the Oregon State Highway Department before enlisting in the Armed Services. Mr. Armstrong returned to the Highway Department following the First World War in 1919, and through the years to 1948 had risen in the hierarchy to assistant maintenance engineer and engineer for county and city relations.

After 1950, the State Parks organization took on a more traditional character in which the parks superintendent became the executive officer for a group of specialized staff and park managers. The Armstrong period marked the transition from the dominance of the founding superintendent to broader, more equal participation by management specialists. It took many years for the park managers to be designated as managers rather than caretakers, but in the 1950s, field personnel were engaged in more than caretaking. They were providing developments to make the parks useful to the public. In fact, Chet Armstrong was directed by the Highway Commission to emphasize park development in lieu of acquisition. He entitled his tenure (1950-1960) as the Construction Period. [1]

Work began on the overnight camps at Silver Falls and Wallowa Lake parks in 1951. Early in that year, a complete survey was made of all Oregon state park units to ascertain the attractions and development potential, particularly for overnight camping. As a result, unimproved camps were developed in 27 parks in 1952. Initially, the camps had four to 15 sites with a table, fire grate and community restrooms.

The camps were very popular with the 44,112 campers who used the facilities when they were opened in the first year. [2] Ultimately, complete developments were made at minimally improved parks, as for example at Cape Lookout. There, an access road was built to Jackson Creek, where parking and picnic facilities and beach access were provided. A large camping area was constructed south and east of the sand dunes at the foot of Netarts Bay marsh, on land given in trade by the Louis W. Hill Family Foundation. The park, previously accessible only by trail, became popular overnight. For years, the campground has been filled to capacity in the summer.

As might be expected, the new road also provided access for adjoining land owners to log their timber. Tillamook County pressed to have a road built over the cape to Sandlake. The resulting development in and around Cape Lookout was typical of much of the improvement in the 1950s, in that roads were the key to make areas accessible for outdoor recreation.

Large seashore camps were built at Honeyman State Park, Umpqua Lighthouse, Humbug Mountain, and Harris Beach. A different approach was followed at Oswald West State Park, south of Cannon Beach. This park had an extensive trail system constructed in the 1930s. Rather than extend the road from the Coast Highway to Short Sand Beach, the trail was used and a walk-in primitive camp development was made in the old-growth spruce-hemlock forest between the highway and the ocean.

Other campsites were developed along the Columbia River and at parks in central and eastern Oregon. Among these developments were Viento State Park, west of Hood River; Tumalo State Park near Bend; the Cove Palisades near Madras, and Emigrant Springs and Hilgard Junction state parks between Pendleton and LaGrande. In the Willamette Valley, besides Silver Falls State Park, camping areas were established at Champoeg, Maud Williamson, Detroit Lake, Cascadia, and Armitage state parks. East of Roseburg, a camp area was created at Susan Creek State Park on the North Umpqua River.

In the first two years of Mr. Armstrong's tenure, the State Parks staff was expanded to 119 permanent employees, including 19 office staff. [3] The addition of planning and engineering personnel accounted for a large part of the increase. Technical assistance also was received from other branches of the Highway Department for such purposes as construction, design and land acquisition. In the period 1950-1960, a new management style was established in which more responsibility was delegated to field managers working in coordination with the Salem office. Though there had been some steps in this direction during the Boardman years, delegated authority did not come to the fore until the post-war era. At this time also, outside organizations and citizen groups more directly affected park system expansion.

One of the citizen groups to have a strong impact on the State Parks organization was the "Save the Gorge" committee of the Portland Women's Forum. It was organized primarily by Gertrude Glutsch Jensen, who was concerned with the effects of logging in the Columbia River Gorge. With the help of others, the committee encouraged the 1953 Oregon Legislature to pass an act establishing a Columbia River Gorge Commission. [4] Funding for the commission came slowly at first. However, in 1955, the Highway Commission set aside a sum of $50,000 to acquire park lands in the gorge between Wygant State Park and the Sandy River. Additional funds were provided later. The State Parks organization cooperated in the effort to secure property. Land exchanges were effected with the U. S. Bureau of Land Management, the U. S. Forest Service and Hood River County. The state of Oregon continued to purchase and receive gifts of land to enlarge its holdings in the gorge.

In addition to promoting the protection and management of areas in the gorge of historic, recreational and scenic interest as publicly-held lands, the Columbia River Gorge Commission sought cooperative agreements, zoning ordinances and other measures to protect natural scenic conditions on private land. As a result, Multnomah County zoned its portion of the gorge against indiscriminate commercial and industrial development, and the state designated as "scenic areas" the new interstate highway from Celilo west to the Sandy River, and the old Columbia River Highway (Scenic Route) from Dodson west to Dabney State Park. Certain private land owners declared interest in protecting the scenic quality of their lands. [5]

For some years, there had been an interest in a separate parks department unassociated with the Highway Commission. Sam Boardman wrote about the problems associated with parks operations governed by the Highway Commission. While he considered the possibility of a separate organization, he never openly sought it. [6] In 1955, Governor Paul Patterson requested the Highway Commission's Advisory Committee on Travel Information to study the question of whether the administration of State Parks should continue under Oregon State Highway Commission direction or under an entirely new agency. [7] The inspiration for this action appears to have come from Thornton Munger, then active with the Portland Chamber of Commerce, and it had the endorsement of the Legislative Interim Committee on Highways. [8] The advisory group embarked on the study using a six-point plan. The plan included field trips to ascertain how the neighboring states of Washington and California were operating state park systems and compilation of an inventory of Oregon state parks, their facilities and past and current expenditures. The State Park Study and Advisory Committee advocated such measures as publicizing state parks to increase their use and scheduling hearings to learn public desires concerning state parks. Its report of findings, including recommendations for the future administration and management of Oregon State Parks, was submitted to Patterson's successor, Governor Elmo Smith, in July 1956. [9]

Not surprisingly, the committee's conclusion was that "so long as parks are financed solely from highway revenue, jurisdiction should remain with the Highway Commission." [10] Furthermore, the committee suggested the creation of an advisory board of citizens, nominated by the Highway Commission and appointed by the governor, representing broad public interests, to function as an agency of the Highway Commission. The board would relieve the Highway Commission of much of its detailed work concerning proposed new areas and programs. It would advise on policy matters and budgets, conduct legislative studies and recommend needed park law changes to the legislature. The new advisory board would undertake additional studies for future park programs, development of county park and recreation departments and coordination and cooperation among federal, state and local park agencies. [11] In August 1957, a Parks Advisory Committee was appointed by Governor Smith. Commencing in 1958, the Parks Advisory Committee met regularly with staff to review park matters. Its members enhanced their capability as advisors to the Highway Commission by means of annual park inspection tours. The advisory body continued to guide and shape state park and recreation policies and programs for 31 years.

In 1956, the State Parks organization had produced "A 20 Year Program for Oregon State Parks." [12] It is interesting to note park visitor use 20 years in the future was estimated at far below the actual use in 1976. Maximum attendance was projected at 15,000,000 in 1956; actual figures for 1976 were 30,852,000. [13] Clearly, promoting visitor use was not a primary need of the Oregon State Parks system. The challenge came in providing adequate service area and facilities in parks while at the same time adequately protecting natural areas, particularly on the coast.

The first formal statement of administrative policy was developed for Oregon State Parks in 1957 by Richard C. Dunlap, Parks planner. Criteria for the acquisition of park areas were specified as follows: accessibility to the public, recreation attractions, natural features and geographical balance. Oregon's parks were to be developed to meet public recreational needs. They were to be maintained in a neat and sanitary fashion with roads maintained by the Oregon Highway Department. Oregon's state parks were free to public entry with fees charged only for special services, such as overnight camping, electrical hook-ups for trailers and so on. River, stream and lake access was to be provided where possible in park areas. Non-conforming uses, such as grazing and salvage logging, could be allowed if not detrimental to park interests. Hunting was generally prohibited in state parks.

In 1957, the decision was made to have park field employees wear uniforms so as to be easily identified by the public seeking information and assistance. The original uniforms were gray with green shoulder patches. The uniform proved popular with park visitors. [14] Although some windthrown spruce-hemlock had been salvaged in 1943 from Joaquin Miller Forest Wayside, south of Florence, most downed or dead park trees had remained untouched in the Boardman years. After very heavy winds damaged large sections of forest on the Oregon coast in the winter of 1951-1952, the policy with regard to park forests was updated. Numerous salvage sales were carried out along the coast and on the Salmon River and Sunset highways. Dead and downed timber was sold if removal did not impair park values. [15] In the 1950s, there was a very active market for all sawlogs, and trespass removal of green timber was a problem in the state parks. Much tree planting was carried out in areas cut in trespass or burned by forest fires.

In accordance with the report of the State Park Study and Advisory Committee, best known today as the Tugman Report (for the committee chairman), the 1959 Oregon Legislative Assembly amended existing statutes concerning state parks and renamed the organization State Parks and Recreation Division. A position of recreation director was created to aid the establishment of recreation programs by small communities and counties in Oregon. [16]

In 1959, it seemed advisable to reiterate the economic benefits of keeping the State Parks and Recreation Division under the wing of the Oregon Highway Department. A division report stated: "The economical operation of state park areas can be attributed to the relationship of the park organization to the Highway Department, including the close cooperation that exists. For example, in 1958 Oregon ranked 3rd lowest in the nation in operation and maintenance costs per park visitor, meanwhile serving 10,528,675 visitors, which ranked 6th highest. Our cost per visitor was 7.8 cents, while the national average was 23.2 cents." [17]

The statement enumerated the various cooperative arrangements forged with units of the Highway Department. The list was substantial. In June of 1960, the Highway Commission moved to improve administrative operation and effect economy of talent. Mark H. Astrup, Highway Department landscape engineer, became deputy State Parks superintendent under C. H. Armstrong and was assigned as a part of his duties the responsibility of directing a special study of needs, objectives and costs of state parks, roadsides and recreational facilities. [18]

The special study provision was consistent with a nationwide effort underway to study the outdoor recreation needs and resources of the United States. Created by act of Congress in 1958, the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC), chaired by Laurence Rockefeller, instituted and supported studies in all facets of outdoor recreation, using 1960 as the base year. The ORRRC report, Outdoor Recreation for America (1962), set a pattern for diversification and development in state park activities, including new matching federal funding for statewide comprehensive outdoor recreation planning.

When Chester Armstrong completed his tenure as State Parks superintendent in December of 1960, park personnel had increased to some 150 year-round staff, plus about 65 seasonal field employees. Taking into account various land exchanges, the number of state park units stood at 176, located on 60,139 acres. [19] He had opened the parks to public use by development and made the maximum use of Highway Department resources for the betterment of state parks.

1. Chester H. Armstrong. 1965. History of the Oregon State Parks 1917-1963. Salem: Oregon State Highway Department, 75.

2. USDI, National Park Service. 1953. State Parks Statistics, 1952. Washington. D. C.

4. Gertrude G. Jensen. 1955. "A List of Major Accomplishments in the Preservation of the Columbia Riser Gorge during the Past Four Years." OSPF.

5. Armstrong, op. cit., p. 38-40.

6. S. H. Boardman. 1944. "Facts and Figures Why the State Park Commission Should be Divorced from the State Highway Commission." OSPF.

7. Governor's State Park Advisory Committee. 1956. Report and Recommendations on Oregon State Parks.

8. Thornton T. Munger to S. H. Boardman. June 14, 1952. OSPF.

9. Governor's State Park Advisory Committee. op. cit., p. 7-23.

12. Oregon State Parks Division. 1956. A 20-Year Program for Oregon State Parks. OSPF.

13. Oregon Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 1975-1976. OSPF.

14. Armstrong, op cit., p. 68-75.

17. Oregon State Parks and Recreation Division. 1959. "Economic Benefits of the State Parks and Recreation Division's Relationship with the Highway Department." OSPF.

18. Oregon State Highway Commission to W. C. Williams and C. H. Armstrong. June 8, 1960. OSPF.

19. Oregon State Parks and Recreation Division. 1961. 1960 Progress Report. p. 4. OSPF.

|

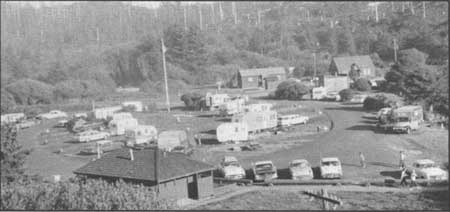

| Fig. 11. Public visitation at Cape Lookout State Park rose sharply following construction of access roads, parking, picnicking and overnight camping facilities. The park had been envisioned by the founding superintendent chiefly as a natural area preserve with an outstanding trail. Here, as elsewhere in the system, Superintendent Chester Armstrong carried out the developments encouraged by the State Highway Commission after the Second World War. A crowded parking lot signified the immediate attraction of new facilities adjacent to the rugged coastal headland and was a forecast of future demand. 1954. Photographer unknown. Oregon State Parks. |

|

| Fig. 12. Chester H. Armstrong, superintendent of Oregon State Parks through the post-war decade, is pictured on the occasion of his retirement banquet in 1960. Mr. Armstrong directed the first intensive development of the state park system. In retirement, he compiled a history of the Oregon state parks that was published by the State Highway Department in 1965. Photographer unknown. Oregon State Parks. |

|

| Fig. 13. Gertrude M. Chamberlin, photographed at the same occasion, served as secretary and office manager under superintendents Boardman and Armstrong and their successors. 1960. Photographer unknown. Oregon State Parks. |

|

| Fig. 14. One of the earliest and most heavily used overnight campgrounds constructed in the post-war era was at Beverly Beach State Park on the central Oregon coast north of Newport. Bottom land along Spencer Creek was easily accessible from the Coast Highway and afforded level ground for development. The logged area in the background now supports a good growth of new forest. 1961. Travel Information Photo. Oregon State Highway Department |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

overview2.htm

Last Updated: 06-Aug-2008