|

OREGON'S HIGHWAY PARK SYSTEM: 1921-1989 An Administrative History |

|

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW (continued)

THE ERA OF DIVERSIFICATION AND DEVELOPMENT

On January 1, 1961, Mark H. Astrup became State Parks superintendent. Educated as a landscape architect at what is now Oregon State University, Mark Astrup had been a candidate for the position in 1929, when Sam Boardman was appointed, and had served as assistant to the Parks superintendent in the period 1946-1948, before becoming landscape engineer for the Oregon State Highway Department. Prior to World War II, he worked with the National Park Service as a landscape architect designing betterment work carried out by the Civilian Conservation Corps at the height of the Depression in Washington, Oregon and California. While in Oregon, he had worked with Sam Boardman trying to develop a central state planning unit for improvement work in the Oregon State Parks.

Though Astrup's tenure as Parks Superintendent was brief, a number of advances occurred under his leadership. Lands for six new state parks were acquired in whole or in part. The statewide comprehensive outdoor recreation planning process was started with Oregon Outdoor Recreation, the study of non-urban park areas prepared under the direction, first, of Richard C. Dunlap and, finally, Richard I. McCosh, who headed the advanced planning unit consecutively. Published in the spring of 1962, the study concerned supply and demand for outdoor recreation in Oregon, as well as public agency responsibilities in this regard. Recommendations were made for the future of parks and recreation in Oregon, paying particular attention to the role of federal agencies, which control 52 percent of Oregon's landbase. [1]

In March, 1962, due to the accelerated highway construction program in Oregon, a landscape section was created in the Highway Department's construction division, and Mark Astrup was appointed its supervisor. [2]

Astrup's replacement as Parks superintendent was Harold Schick, who officially took charge July 1, 1962. Schick was a professional park manager educated at Michigan State University and the University of Michigan. He had been serving as the first superintendent of the newly-formed regional park and recreation agency for the city of Salem and Marion and Polk counties.

With the aid of federal and state funds, land acquisition for parks expanded, especially on the Oregon coast. After careful consideration of park values, the Highway Commission protected the Nehalem Sand Spit as a state park rather than allow its use for shorter route relocations of the Oregon Coast Highway. The assistant Highway engineer was the liaison, or intermediate position in the chain of command between the State Parks superintendent and the Highway engineer. His support on policy matters was crucial. Popular park programs advanced by professional staff and backed by the Highway Department's top management enhanced the public image of the Highway Commission and the Highway Department.

In the early 1950s, initial efforts in park interpretation were begun at Fort Stevens State Park near Astoria. The program included a nature trail, and talks were given by seasonal personnel, often students from college programs specializing in visitor interpretation. Though local people at times opposed the expenditure for such programs, a report on state park visitor use which pointed out visitor expenditures in communities adjacent to park areas won their support. [3] The State Park Visitor Survey carried out by questionnaire in 19 state parks during the summer of 1964 was repeated on a recurring basis in succeeding years. Much of park planning was based on visitor surveys. [4]

In December, 1964, Harold Schick moved on to become director of the Fairmount Park Commission in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. [5] He was succeeded by David G. Talbot, the present director of the Oregon State Parks and Recreation Department. Though a Californian by birth, Talbot was raised in Grants Pass, in southern Oregon. He received B.S. and M.S. degrees in parks and recreation administration from the University of Oregon. After an early appointment as director of parks for the city of Grants Pass, he had come to the State Parks and Recreation organization in 1962 as state recreation director.

One result of Oregon Outdoor Recreation, the statewide non-urban parks and recreation study of 1962, was the realization by the Highway Commission of the ever increasing demand for public recreational areas and facilities, particularly for camping. Accordingly, the Parks and Recreation budget was increased substantially in the 1963-1965 biennium to help with land acquisition and development. Further, in the 1965-1967 biennium an additional $2.5 million was provided for these purposes. Major efforts were made on the coast, with expansion in other parts of the state as opportunities arose. [6]

In the 1960s, State Parks land acquisition policy was to acquire key tracts of land, but to limit purchase of private land. The federal government was encouraged to transfer surplus lands to the state for park purposes. Oregon law in 1963 authorized the Highway Commission and, therefore, the Parks agency to acquire and develop scenic or historic places.

In 1966, Oregon's park costs per visitor were the lowest in the United States at some 10 cents per taxpayer as compared to an average nationwide operation and maintenance cost of 25 cents. [7] Following a recommendation of the National Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission, the United States Congress in 1964 passed the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act, which provided a fund to assist state and federal agencies in meeting public outdoor recreation needs. [8] In Oregon, the federal matching grants aided state recreation planning, development and acquisition. In addition, pass-through grants (45 percent of the allocation) were funneled to local governments for recreation development and acquisition. Coordination of this work was delegated to the state recreation director in the Parks and Recreation Division. Thus, the State Parks and Recreation Division became a focal point for coordinating federal, state, local and private efforts in outdoor recreation. The agency also acquired the responsibility for state-wide comprehensive outdoor recreation planning.

Use of the Oregon State Parks system rose to 16 million visitors in 1965, up over nine million from 1955 visitation and some four million over 10-year projections made in 1956. [9] Visitation intensified at coastal parks, and there was increasing interest in protection of the Oregon beaches. As was earlier described, in 1913 Governor Oswald West had asked the legislature to proclaim Oregon beaches a public highway. This was done by legislative act and included unsold tidelands from the Columbia River to the California state line. By the 1960s, it was apparent that open public access to ocean beaches was limited in some areas. [10]

Following recommendations in the 1962 study, Oregon Outdoor Recreation, and encouraged by the Highway Commission and Parks Advisory Committee, the Parks Division started a major beach access acquisition program. The objective was to encourage recreational use of ocean beaches and prevention of private access control. From the outset, the policy was to provide a public day-use beach access point at least every three miles the length of the coastline.

Despite legislative action to reclassify the tidelands as state recreation areas in 1965 and the shaping of outdoor recreation policy accordingly, problems arose with regard to private development intruding onto the beaches. It was determined that the state's legal jurisdiction was limited landward of the high tide line. [11] Legislation was necessary to protect public beach land from the high tide mark to the vegetation line and prevent exploitation for private gain.

Following a test of the public access rights to the shore at Cannon Beach and considerable furor reflected in the media and in the legislative proceedings, a beach protection bill was passed by the Oregon Legislature and signed by Governor Tom McCall on July 6, 1967. This vested ocean shore public rights in the state of Oregon. After the law was enacted, a survey was made to establish a permanent landward public beach zone line. [12] The survey points were approved by a legislative act signed into effect by Governor McCall in 1969.

Though the beach law was generally supported by the public, with the Oregon State Parks organization looking after its interests, two lawsuits over encroachments into the public zone were filed shortly after its passage. In both cases, the law was upheld. [13] In a later case (1987-1989) concerning a tide pool at Little Whale Cove in Lincoln County, the suit claiming a violation was lost, but the law was supported by a precise definition of beach boundaries.

A coastal feature of great recreational interest is the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area, which extends from the Siuslaw River south to the Coos River. Long a part of the Siuslaw National Forest, this area was proposed as a National Seashore by the National Park Service about 1959, and details of the recommendation were presented to the State Parks Advisory Committee. Originally, the bounds of the reserve proposed by the National Park Service included the privately-owned Sea Lion Caves north of Florence as well as Jessie M. Honeyman Memorial State Park. There was considerable opposition to the proposal locally. The U. S. Forest Service at first was not enthusiastic, and the State Parks Advisory Committee asked that Honeyman Park be excluded. After much public discussion and the introduction of several trial bills in the Congress, a bill creating an Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area (NRA) to be administered by the U. S. Forest Service was passed by Congress and was made law in 1972. Later, lands at Umpqua Lighthouse State Park were traded to the Forest Service National Recreation Area for equivalent parcels added to the State Parks system elsewhere.

The Oregon Dunes NRA now includes 32,185 acres and adjoins Honeyman and Umpqua Lighthouse State Parks. It is most popular, particularly with dune buggy recreationists, and its use both complements and complicates that of the state parks. [14]

Another federal area that originated as a series of state parks is the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, now administered by the National Park Service. As was mentioned earlier, the area was promoted in the period 1920-1945 by such figures as R. W. Sawyer, Sam Boardman, John C. Merriam and the State Board of Higher Education Advisory Board on State Parks. Three parks were created over a wide area in Grant and Wheeler counties: Thomas Condon-John Day Fossil Beds, Clarno and Painted Hills state parks. Adequate management and interpretation of the parks always was a problem. In 1967, at the request of Oregon Congress man Al Ullman, the National Park Service evaluated the natural, scientific and recreational resources of the John Day Basin. While Park Service officials found the geological and paleontological resources of national significance and suitable for National Monument status, other recreational and scientific features were said to be of state or local interest. [15]

The State Parks agency and its advisory committee encouraged further federal studies with a view to federal development and administration. [16] Ultimately, the land was transferred to the federal government, and the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument encompassing 4,345 acres was created in July, 1975.

During this period there was a growing concern for the protection and recreational use of the Willamette River corridor from Dexter Reservoir in Lane County north to the Columbia River, west of Portland. A key figure in generating concern for the Willamette River was Karl W. Onthank, conservationist and long-time faculty member and administrator at the University of Oregon in Eugene. [17] This interest was highlighted in the gubernatorial campaign of 1966 and addressed by both candidates. On February 2, 1967, early in his term of office, Governor Tom McCall issued an executive order creating a Governor's Willamette River Greenway Committee, which was to recommend boundaries of a Willamette River greenbelt and report on ways and means of securing state jurisdiction over lands adjacent to the river. The State Highway Commission, through its Parks and Recreation Branch, was given responsibility for implementing the order. The committee included six citizen members, affected county and city officials, and other representatives. [18] C. Howard Lane of Portland was the original chairman.

The legislature supported the concept in statute in 1967 but elicited a temporary name change to "Governor's Willamette River Park System Committee" to assuage the concerns of private land owners. As developed under the direction of George W. Churchill of the State Parks and Recreation Branch, the Willamette River Parks plan emphasized acquisition and development by local government with regulatory functions, grants and technical assistance provided by the State Parks agency. The monies passed through to local governments were obtained in part from the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund.

A number of local parks were created along the Willamette River, but there was considerable opposition from farm land owners. In 1973, the Oregon Legislature revised the law to protect farmers and to require the State Parks agency to develop and adopt a Greenway Plan, which also would be adopted by the new Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC). After much controversy, LCDC adopted the Greenway Plan and established boundaries in 1976. In the next three years, three new regional state parks and 43 recreation areas were developed along the Willamette. Although the Greenway planning concept continues, a shortage of funds in recent years has limited further acquisition of lands or development of facilities. [19]

Earlier, in 1970, the voters passed an initiative establishing an Oregon Scenic Waterways Act that designated six rivers to be preserved in their natural free-flowing condition. The rivers were the Minam and segments of the Deschutes, Illinois, John Day, Owyhee and Rogue Rivers.

The Oregon Transportation Commission, through the State Parks and Recreation agency, was given responsibility for managing programs under the Scenic Waterways Act. [20] The program managers are aided by the Governor's Scenic Waterways System Committee. The program protects the aesthetic and scenic values of the waterways by promoting compatible uses of adjoining lands. There also is a governor-appointed citizen advisory group, the Deschutes River Scenic Waterway Recreation Management Committee, which is assembling a recreational use and development plan for the lower Deschutes River. In 1988, Oregon passed Ballot Measure 7, which increased the system of protected waterways to 19 rivers and Waldo Lake, and the federal Oregon Omnibus Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1988 added a number of rivers under U. S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management administration. [21]

Where recreation use and conservation matters are in potential conflict, careful planning and control are necessary to protect quality recreation and scenic values. The first statewide management plan for scenic waterways was developed in 1971. [22]

In 1971, the Oregon Legislature passed the Oregon Recreation Trails System Act to provide for expanding recreation needs and protect public access to the outdoors, whether near urban areas or highly scenic wilderness locations. [23] The State Parks and Recreation agency was directed to coordinate an interconnected system of hiking, horseback, biking, and bicycle trails. The most notable of these are the Pacific Crest Trail, which is part of a national system and follows the length of the Cascade Range, and the Oregon Coast Trail, which links parks along the coast from Astoria to Brookings. A State Recreation Trails plan was completed in 1979 and a Recreation Trails Advisory Council helps to guide administrative policy. [24]

At the same time concern was being expressed about preservation of scenic and recreational assets, such as the Willamette River and other Oregon waterways and trails, there was a parallel interest in the preservation of historic sites and buildings. In 1966, Congress enacted the National Historic Preservation Act, which provided for a national program to inventory, register and protect places of historic interest. A program of federal matching grants-in-aid was created and, in Oregon, the Parks and Recreation agency administered it. Initially, the state Highway engineer acted in the capacity of state liaison officer for the historic preservation program, but the State Parks superintendent was designated state historic preservation officer in 1973. [25] In 1969, the first matching funds for development of the Statewide Inventory of Historic Properties were obtained from the U. S. Department of the Interior.

The State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), a special program unit of the Parks and Recreation agency, administers the details of the 50/50 match-fund program. Its duties under law and rule involve regulatory procedures with regard to federal undertakings; survey, inventory and planning functions; registration of properties; and grants management. [26] The office is advised by the Governor's State Advisory Committee on Historic Preservation.

Administratively, the most important change in the 1960s was creation of the State Department of Transportation by the Oregon Legislature in 1969. The new department (ODOT) consolidated the Highway Department and its Parks Branch with Motor Vehicles, Aeronautics, Ports and Mass Transit under the control of a State Transportation Commission. The State Parks and Recreation Branch continued as an administrative unit of the ODOT Highway Division until 1979, when, by action of the Oregon Legislature, it became a separate and co-equal division of the Department of Transportation. With this development, the title of State Parks superintendent was changed in conformance with the statute to State Parks administrator. [27]

Early in this period, after having consulted with the State Parks superintendent, the Metropolitan Parks Foundation of Portland sought approval of the city of Portland and the State Transportation Commission to become the Oregon Parks Foundation. As reorganized on a statewide basis in 1972, the foundation encouraged the growth of parks and recreational facilities in all parts of the state and by all units of government. Toward this end, it was set up to accept donations and hold prospective park property for the short term. The Oregon Parks Foundation has been directly responsible for adding significantly to open space in the public domain since it was incorporated.

1. Outdoor State Parks and Recreation Division. 1962. Oregon Outdoor Recreation: A Study of Non-urban Parks and Recreation. Salem: Oregon State Parks and Recreation Division.

2. Oregon State Highway Department. Division of Personnel and Public Relations release. March 22, 1962.

3. Interview with Harold Schick. Jefferson, Oregon, November 15.1989.

4. Oregon State Parks and Recreation Division. 1964. "The State Park visitor in Oregon." OSPF.

6. David G. Talbot. Remarks before the Legislative Interim Committee on Highways, Salem, February 17, 1966. p. 3.

8. Public Law 88-578, Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965.

10. Kathryn A. Straton. 1977. Oregon's Beaches: A Birthright Preserved. Salem: Oregon State Parks and Recreation Branch, p. 11, 18.

13. Straton. op. cit., p. 49-54.

14. Siuslaw National Forest. 1966. Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area general information.

15. Theodore R. Swum to Governor Tom McCall. January 22, 1968. OSPF.

16. David G. Talbot to State Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee. March 1, 1968. State Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee minutes.

17. Thomas R. Cox. 1988. The Park Builders: A History of State Parks in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 140ff.

18. Oregon State Governor's Office. Executive Order No. 67-2. February 2, 1967. OSPF.

19. Oregon State Parks and Recreation Division. 1987. Willamette River Greenway. Draft vision statement for the 20-year plan (2010 Plan).

20. ORS 390.805. to 390.940. Scenic Waterways.

21. Oregon State Parks and Recreation Division. 1988. Oregon State Parks 2010 Plan.

22. Oregon State Parks and Recreation Division. 1987. Scenic Waterways. Draft vision statement for the 20-year plan (2010 Plan).

23. ORS 390.950 to 390.990. Recreation Trails.

24. Oregon State Parks and Recreation Division. 1988. Oregon State Parks 2010 Plan.

25. Oregon State Historic Preservation Office. Statewide Comprehensive Historic Preservation Plan, 1989.

26. Oregon State Parks and Recreation Division. 1988. Oregon State Parks 2010 Plan.

27. L. L. Stewart. Chairman, State Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee. Committee minutes. April 18, 1980.

|

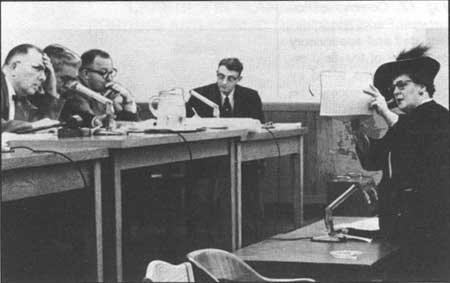

| Fig. 15. Gertrude Glutsch Jensen, long-time leader of the Portland Women's Forum and original chairman of the Columbia River Gorge Commission, devoted many years to crusading for scenic protection within the Columbia Gorge. She is pictured here in the statehouse, on March 2, 1955, presenting her case for an appropriation of funds for coordinating activities during a hearing before a subcommittee of the Senate committee on ways and means. Subcommittee chairman Francis W. Ziegler of Benton County is seated with his panel on the far left. Oregon Journal Photo, Oregon Historical Society, #OrHi 86990. |

|

| Fig. 16. Arthur M. Burt, supervisor of State Parks Region I from 1954 to 1967, is shown receiving from Parks Superintendent Harold Schick a lapel pin acknowledging combined service in Highway maintenance and Parks organizations of 35 years. A Parks employee awards program was founded on his exemplary record. The first annual Art Burt Award for outstanding performance among field personnel was presented in 1982. Under Superintendent Schick, some of the first professionals trained in the relatively new scholastic discipline of parks and recreation administration were brought to the staff. c. 1963. Photographer unknown. Oregon State Parks. |

|

| Fig. 17. Communication between Parks headquarters staff and supervisory personnel of the field organization was aided by periodic conferences in the State Highway building in Salem. This exchange was photographed during the tenure of Harold Schick, 1962-1964. At the head table, from left: L. V. Koons, deputy Parks superintendent; Warren Gaskill, field operations chief; Superintendent Schick; P. M. Stephenson, assistant Highway engineer; Cliff Lenz, Region I supervisor. Other Region supervisors present but not included in the camera view were: Art Burt, Region I; Otis Jensen, Region III; Al Zimmerman, Region IV; and Frank Stiles, Region V. c. 1963. Photographer unknown. Oregon State Parks. |

|

| Fig. 18. Among members of the field organization pictured are, left to right: Darald Walker, Cape Lookout; Ray Leavitt, Fort Stevens; O. J. Shaw, Champoeg; Ken Stenger, The Cove Palisades; Joe Davis, Fort Stevens; Leon Stumpff, Robert W. Sawyer; Owen Lucas, Coquille Wayside; Ion Herring, Jessie M. Honeyman; Gordon Grassick, Latourell Falls; Dale Hoeye, Harris Beach; Ken Lucas, Neptune; Joe Ficek, Devil's Lake; Gerry Lucas, Salem; Roland LeCompte, Silver Falls; Harry Luckett, Silver Falls; Wally Eldredge, Umpqua Lighthouse. Among others present but not included in the camera view were George Guthrie, Tou Velle State Park, and Don Pizer, Yaquina Bay. c. 1963. Photographer unknown. Oregon State Parks. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

overview3.htm

Last Updated: 06-Aug-2008