|

Rainbow Bridge

A Bridge Between Cultures: An Administrative History of Rainbow Bridge National Monument |

|

CHAPTER 3:

Searching for Rainbows: The Cummings/Douglass Expedition

The push to make Rainbow Bridge and its immediate environs a national monument began immediately after it was sighted by two men: William B. Douglass, Examiner of Surveys for the General Land Office (GLO), and Professor Byron Cummings, a part-time archeologist and professor of ancient languages from the University of Utah. This chapter details the story of how these two men came together and put Rainbow Bridge on the evolving map of Utah's canyon country. The story of Rainbow Bridge's first official sighting is a controversial tale. Supporters of Douglass and Cummings have leveled numerous accusations at each other over the years. Debates over who led whom to the bridge, which Native American guide had the most immediate knowledge of the trails, and who actually sighted the bridge first are all part of the dispute. More important than the truth of individual claims to glory is the fact that having located the bridge for both science and government, the first official expedition made preserving the bridge a national concern. In addition, the controversy over who discovered the bridge in 1909, while academic at best, was only the first of many disputes that focused on Rainbow Bridge.

In his camp at Grayson, Utah, William Boone Douglass contemplated the fate of a little known stone edifice. On October 7, 1908, Douglass wrote to the Commissioner of the GLO regarding new information about an enormous, white sandstone bridge that was "like a rainbow," and which had a span greater than the Augusta Bridge in the recently created Natural Bridges NM. [76] Douglass admitted in his letter that this information came to him in early September from a Paiute Indian named Mike's Boy, also known as Jim Mike. Mike's Boy had been in Douglass's employ as an axeman. At nearly the same time, a hundred miles away in Oljeto, Utah, the same information was being passed between two other people. Byron Cummings, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Utah and an amateur archeologist, was near Oljeto excavating sites at Tsegi Canyon in August 1908. Cummings learned of the possible existence of a massive arch from John and Louisa Wetherill, who owned and operated the trading post at Oljeto. [77] Wetherill and Cummings made plans for an expedition to the bridge for the summer of 1909. Eventually, Cummings and Douglass joined forces in August 1909 and completed the first successful expedition to Rainbow Bridge.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the American Southwest was a hotbed of archeological exploration and excavation. Richard Wetherill, John's brother, discovered Cliff Palace Ruin in 1888. The Wetherill family owned a cattle ranch near Mancos. Colorado. Richard Wetherill happened upon the immense ancestral Puebloan structures at Mesa Verde while chasing stray cattle with his brother-in-law, Charlie Mason. Of all the sites at Mesa Verde, Cliff Palace was the most spectacular. All the Wetherill brothers had cursory knowledge of abandoned dwellings in the Mancos area. In 1887, Al Wetherill stumbled upon the first of the Mesa Verde dwellings, Sandal House. After 1888, the Wetherills, especially Richard, developed more than a passing interest in prehistoric cultures. Richard Wetherill believed he had discovered a "lost civilization" and was consumed with the pursuit of discovering more sites. [78]

There were very few uniform standards for American archeologists in the late 19th century. In the Southwest, archeologists without any institutional affiliations were considered buffs at best and "pot hunters" at worst. Even the idea of valuing the past for its scientific or historical merit was not well established in the American Southwest. Preservation as a guiding principle was new to the federal bureaucracy that was just starting to manage America's public lands. But the ethos was forming. The federal government began to recognize the value of preserving scenic natural resources, translating that recognition into legislation with the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, as well as three more national parks in California in 1890 (Kings Canyon, Sequoia, and Yosemite). In 1892, President Benjamin Harrison signed an executive order that reserved the Casa Grande Ruin and 480 acres around it for permanent protection because of its archeological value. More and more federal agencies, as well as professional organizations like Edgar L. Hewett's Archeological Institute of America (AIA), realized that the vast federal estate needed management and rules. The evolving disciplines of anthropology and archeology were struggling to achieve legitimate scientific status in America during the late 1880s. Protection and preservation of America's past slowly became one of the goals of post-1890s society.

In this historical context, Richard Wetherill's practice of excavating for profit, even shipping artifacts overseas with men like Gustav Nordenskiold of Sweden, was much less controversial. The debate in the scientific community over how to preserve America's scientific and cultural past was still evolving. [79] It would be unfair to disparage Richard Wetherill from the vantage point of the early 21st century. Scientific preservation was in its infancy in the 1890s, and there was no reason for Richard Wetherill to feel an innate compulsion to save his discoveries for future generations of Americans. He was not alone in his desire to profit from past. But his practices were at odds with the evolving ethos of preservation. Wetherill represented the kind of "pot hunting" that American academics and scientists were trying to move away from. That Wetherill was so successful at finding abandoned dwellings and so undaunted by the criticisms of "professionals" made him an anathema to many. The fact is that many "archeologists" of the period engaged in the same practices as Wetherill. It would be hard to describe any of them as more than collectors of artifacts. Scientific processes such as dating sites, cataloging artifacts, preserving finds for future generations, or even publishing the results of excavations were not part of the regimen for most archeologists in the late 19th century Southwest. Ironically, these same "professional" organizations were trying to distance themselves from the amateurs they thought of as detrimental to their professional prestige. Regardless of the competing ethical interests, it was the professionals and academics who had the ear of Congress.

| |

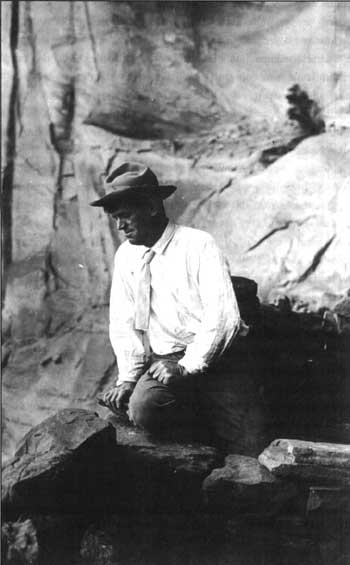

| Figure 9 John Wetherill (Stuart M. Young Collection, NAU.PH.643.4.13, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University) | |

The push to legislate scientific preservation began in earnest at the beginning of the 20th century. Various organizations, such as the American Anthropological Association and the AIA, sought protective legislation that would prevent further export of Southwest Indian artifacts. Edgar Hewett and the AIA found an able supporter in Representative, John F. Lacey of Iowa. Lacey was known for his belief in the preservationist ethic and more importantly for his ability to translate that ethic into legislation. In 1900, Lacey introduced legislation to create a federal administrative entity responsible for managing America's national parks. Though this bill was defeated, Lacey continued to fight for the protection of valuable scientific and natural resources. In 1901, he secured passage of the first comprehensive federal legislation designed to protect wildlife, the Lacey Act, which criminalized the interstate shipment of any wild animals or birds killed in violation of state laws.

After hearing about the high rate of artifact exportation in the Southwest, Lacey met with Edgar L. Hewett to discuss preservation of American archeological sites. At their meeting, Hewett presented a draft of legislation designed to prevent further unauthorized excavation of scientifically significant sites. The legislation also included language to authorize the President to protect such sites through executive order. With some modifications, Lacey introduced the bill to Congress. Other bills similar to Hewett's had been presented to Congress before. Western senators and congressmen had always killed these bills based on their dislike of any enlarged federal presence in the West. But Lacey managed to allay these fears with Hewett's bill. He assured western legislators that the bill's intent was to preserve significant but specific sites, such as Native American cliff dwellings, and would be applied selectively based on scientific rationales. In June 1906, Congress passed "An Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities." [80]

Known as the Antiquities Act, this legislation provided mechanisms to the President "to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments, and may reserve as a part thereof parcels of land, the limits of which in all cases shall be confined to the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected." [81] The act required permits to be approved before archeological investigations could be undertaken inside the boundaries of a national monument. The criteria for designation as a national monument varied from location to location, but was based primarily on a site's scientific or historic uniqueness. The authorizing mechanism was also different from national park legislation, putting the power to preserve in the hands of the President rather than Congress. Federal agencies, private groups, or individuals could lobby the chief executive on a cause and effectively bypass the legislative system that encumbered the process of national park designation.

The first national monument, Devils Tower in Wyoming, was proclaimed by Theodore Roosevelt on September 24, 1906. By the end of 1908, Roosevelt had declared another sixteen monuments, including Gila Cliff Dwellings, Grand Canyon, and Natural Bridges. National monuments customarily remained under the management and supervision of the land management agency that controlled the land at the time of a monument's designation (e.g., the Forest Service, the War Department, etc.). One of those sixteen, Chaco Canyon National Monument, was designated in direct response to Richard Wetherill's homestead claim at Pueblo Bonito. [82] This did not stop Wetherill and others from expanding the search for archeological sites in the region. The non-professionals were not easily stayed.

It was not archeology alone that brought whites to the Rainbow Bridge area. Trade and goodwill played their parts in addition to exploration. By 1908, the American Southwest was still largely unexplored by whites. The area surrounding present day Rainbow Bridge was all part of the Navajo Reservation. During this period of archeological exploration in the Southwest, the Navajo were beginning to prosper economically. Utilizing "seed stock" obtained from the United States military, Navajo herdsmen raised sheep in earnest between 1870 and 1907. Despite difficult winters in 1894 and 1899, reliable estimates placed the Navajo sheep population in 1907 at 640,000 animals. [83] But the Navajo were trapped in the cyclic dependency of sheep herding. As available grazing lands reached maximum capacity, expansion in the region was limited. More and more sheep were being eaten, and less raw wool was being traded despite enormous herd populations all over the reservation. The Navajo were compelled to find another way to convert wool into revenue.

The trading posts that popped up during this period were not popular at first with Navajo elders, nor with herdsmen that found them on the edges of their grazing lands. The Navajo were not tolerant of encroachment by whites so soon after confinement at Bosque Redondo. But trading posts offered a vector of economic exchange that was unavailable before. Navajo blankets and silver work, increasingly popular among Anglos, were sold at regional trading posts and made it possible for non-herding Navajos to improve economically. [84] Trading posts helped the Navajo economy to expand beyond agriculture and livestock. During this 20th century atmosphere of survival and expansion, John and Louisa Wetherill moved to Oljeto and set up a trading post on the Navajo reservation.

John and Louisa Wetherill were experienced traders. At their first outpost, known as Ojo Alamo and located near Pueblo Bonito, New Mexico, Louisa Wetherill befriended local Navajos and began learning the Navajo language. By 1906, Louisa was fairly fluent in Navajo and well acquainted with the culture and custom of local Navajos. [85]

| |

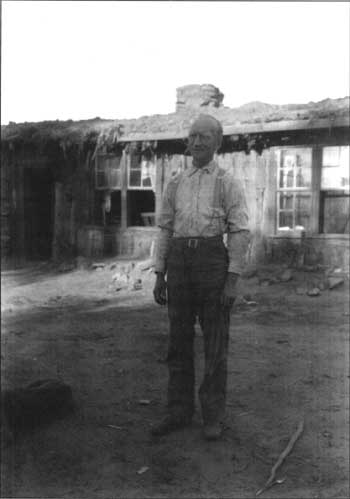

| Figure 10 Byron Cummings (Stuart M. Young Collection, NAU.PH.643.45, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University) | |

In addition to running the trading post, the Wetherills tried their hand at wheat farming. Neither endeavor proved immensely profitable. Trading in the area was limited by numerous factors, and the years between 1904 and 1906 gave the Wetherills three successive wheat crop failures. During this period their family responsibilities grew with the birth of two children, Benjamin Wade and Georgia Ida. Opportunities at Ojo Alamo had run out. What brought the Wetherills to Oljeto was a combination of adventure, frustration with farming, and the desire to run a profitable trading post. The trading post business at Oljeto was built on good will. In March 1906, the Wetherills and their partner Clyde Colville, who had been with them since Ojo Alamo, feasted with two of the most respected leaders of the Navajo Tribe, Old Hashkéniinii and his son Hashkéniinii-Begay. The combination of respect shown to Navajo custom and Louisa's linguistic fluency combined to endear the Wetherills to the local Navajo tribal members. In an area quickly attracting the attention of explorers and government officials, the Wetherills established a firm presence with the "keepers of the rainbow." [86]

Like his brother Richard, John Wetherill had a deep passion for archeology and the history of prehistoric cultures. Ever since the discovery of Mesa Verde, John Wetherill was fascinated by the past hidden in the sandstone of the Southwest. Over the years he collected an enormous amount of knowledge concerning regional ancestral Puebloan sites and developed an intimate relationship with local Indians regarding the whereabouts of unexplored sites. To support his financial needs as well as to satisfy his innate curiosity, John Wetherill hired himself out as guide and outfitter to individuals and institutions seeking artifacts of the southwestern past. It was in this capacity that Wetherill came into contact with both Byron Cummings and William B. Douglass.

Byron Cummings was a typical archeologist of the early 20th century. He came to the West from New York, accepting a position as professor of Ancient Languages at the University of Utah in 1893. By 1905 he was dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and a regular client of the Wetherills. Numerous trips in Utah's south-central desert intensified his love for archeology. He put together teams of students and semi-professionals every summer for romantic journeys into the canyons of Dinétah. Cummings was self-trained and extremely motivated toward exploring and excavating the various sites to which John Wetherill led him. These included Keet Seel, Inscription House, and Betat' akin, all on the Navajo Reservation. [87] In 1907, Cummings and his party generated a topographic map of White Canyon, Utah. The dominant features of the geography were three sandstone bridges, all larger than any previously mapped in the continental United States. After Cummings sent his map to the GLO in Washington, D.C., President William H. Taft declared Natural Bridges NM on April 16, 1908. [88] Cummings embodied the spirit of discovery still budding in American archeology. His concerns were with knowledge and the preservation of scientific data. He was little concerned with regulation or the government's place in the scope of "discovery."

William B. Douglass came to the Southwest as a representative of order and regulation, the twin themes of the Progressive Era. [89] Having worked his way up through the ranks of government service, Douglass was the epitome of the Progressive ideology. He was less concerned with the esoteric value of Native American sites or artifacts than with maintaining the integrity of the federal estate and enforcing the provisions of the Antiquities Act. Douglass believed that structures or artifacts located on federal land were federal property and were therefore subject to federal regulation. The Antiquities Act was a touchstone for Douglass: his reports to his superiors regarding the creation of national monuments at Natural Bridges, Navajo, and Rainbow Bridge were critical to their designations as protected space. Like many bureaucrats at the time working to preserve newly discovered Native American sites or unique geologic structures, Douglass still had a bad taste in his mouth regarding Richard Wetherill. The days of amateur excavation and collection were over and in the mind of a man like Douglass, any hint of their return demanded swift action. [90] Douglass knew that Cummings and Wetherill were in the Tsegi Canyon region and feared that without immediate protection, artifacts from the area would end up in various private museums or collections and the dwellings at places like Keet Seel would be permanently disturbed. In the spring of 1908, after the GLO received Cummings map of White Canyon, they sent Douglass to resurvey the area and define its boundaries more carefully. [91]

William Douglass learned of the possible existence of the great Rainbow Bridge from Mike's Boy, his Paiute axeman. If the bridge existed, Douglass's immediate concern was that site avoid despoliation by amateur explorers. Writing to his superiors, he said:

Mike's Boy [Jim Mike] says no white man has ever seen this bridge, and that only he and another Indian know of its whereabouts. This bridge is in, or near, the oil region; it will undoubtedly be discovered, and as surely located by some kind of claim. I have secured a promise that nothing be said of it until I have had time to learn the wishes of yourself on this subject. [92]

As a prudent government employee of the Progressive Era, Douglass's first concerns were focused on protection and regulation. Whatever his motivations after finding Rainbow Bridge, whatever his actions in the ensuing controversy, his initial consideration was to secure a place for the bridge within the federal estate where it could be managed and protected from all parties that could do it harm.

How Byron Cummings learned of the bridge is a more detailed story. In 1907, Louisa Wade Wetherill was on good terms with the local Navajo population at Oljeto. She had a reputation with her customers for fairness in trade and was considered a healer by many. Her fluency in the Diné language also improved her standing and her ability to gather information. Her maternal nature and stalwart demeanor endeared her to most of her acquaintances. In early 1907, a Navajo named One-Eyed Salt Clansman (Áshiihí bin áá' ádiní) had just returned to Oljeto from guiding a party of whites into the White Canyon natural bridges. [93] One-Eyed Salt Clansman knew of the Wetherills' passion for ancient places and people and inquired about this with Louisa. Author Frances Gillmor, in consultation with Louisa Wetherill, related the story of Louisa's knowledge of the bridge:

The One-Eyed Man of the Salt Clan came to Ashton Sosi [Louisa Wetherill, "Slim Woman"] with a question.

"Why do they want to go?" he demanded. "Why do they want to ride all that way over the clay hills to see—just rocks?"

"That is why they go," Ashton Sosi explained. "Just rocks in those strange forms, making bridges. There is nothing like them anywhere else in the world."

The One-Eyed Man of the Salt Clan considered the matter.

"They aren't the only bridges in the world," he objected. "We have a better one in this country."

"Where is there a bridge in this country?" asked Ashton Sosi.

"It is in the back of Navajo Mountain. It is called the Rock Rainbow that Spans the Canyon. Only a few go there. They do not know the prayers. They used to go for ceremonies, but the old men who knew the prayers are gone. I have horses in that country and I have seen the bridge." [94]

One-Eyed Salt Clansman died in the fall of 1907, before he could guide John Wetherill to the bridge. There are no sources that suggest why an expedition to the bridge was not mounted in the summer of 1907. Gillmor and Louisa Wetherill contend that in the early spring of 1908, Clyde Colville, partner to the Wetherills, employed Luka, Man of the Reed Clan, to guide Colville into the canyons north of Navajo Mountain. After crossing difficult creeks and canyons, Luka admitted he could not find the trail. Even after climbing the northwest slope of Navajo Mountain, Colville never managed to sight the bridge. [95] Rainbow Bridge remained hidden for a few more months.

In August 1908, the Wetherills informed Byron Cummings of One-Eyed Salt Clansman's story of the rock rainbow. Again, there is no explanation why the Wetherills waited until the end of Cummings' latest expedition to pass on this vital information. Nevertheless, Cummings and John Wetherill made definite plans for a summer 1909 expedition to find the bridge. But in the early winter of 1908, William Douglass appeared at Oljeto. That October, Douglass had received approval from the GLO to search for the bridge. He had arranged to meet Mike's Boy at Oljeto soon after breaking camp in Bluff, Utah. Douglass arrived at Oljeto on December 4, 1908. He intended to hire John Wetherill as an outfitter and use Mike's Boy as a guide. But poor supplies, bad weather, and the failure of Mike's Boy to arrive on time combined to cancel the trip. Wetherill also engaged in some slight subterfuge, trying to convince Douglass that Mike's Boy was either wrong about the existence of the bridge or misinformed about its location. [96] In the controversy which erupted after 1909 over who should receive credit for finding the bridge, Wetherill's ploy worked against him. Denying the bridge's existence to Douglass made it seem that any knowledge of the bridge flowed from Mike's Boy to Douglass to Wetherill. Wetherill vehemently denied this assertion in later years. Regardless, Douglass was undeterred by Wetherill's criticism of Mike's Boy and announced he would return the following year for another attempt. By extension, Wetherill knew in December 1908 that Douglass possessed knowledge of the bridge and would try to reach it as soon as the weather permitted. [97]

| |

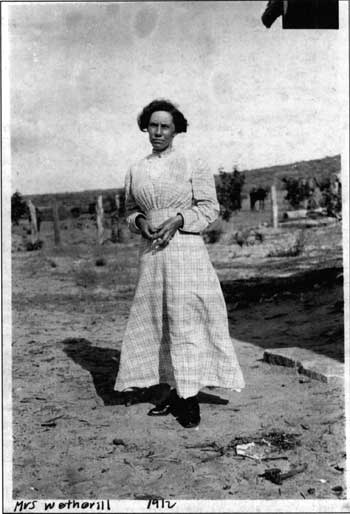

| Figure 11 Louisa Wetherill (Stuart M. Young Collection, NAU.PH.643.4.14, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University) | |

In the winter of 1909, Louisa Wetherill made numerous inquiries of her trading post customers about the location of the bridge and about Indians who might serve as guides. She received an unexpected response in the early spring of 1909. Nasja Begay and his father, both Paiutes, came to do business at Oljeto. They claimed to have seen the bridge only months earlier while searching for stray horses. They agreed to guide the Wetherills to the bridge in the coming summer. [98] It was to be a busy summer for Cummings, Wetherill, and Douglass.

One fact remains troubling in light of the controversy that began after the bridge was found. In July 1909, after Cummings was already in Tsegi Canyon exploring various ancestral Puebloan sites and planning an August expedition to find Rainbow Bridge, John Wetherill mentioned the bridge to an unlikely recipient. Herbert Gregory, a geologist for the U.S.G.S., was near Oljeto conducting a hydrographic reconnaissance of different areas. Gregory must have stopped at Oljeto for supplies and encountered Wetherill. Numerous sources confirm that John Wetherill informed Gregory of the certain existence of the great rock rainbow. [99]

| |

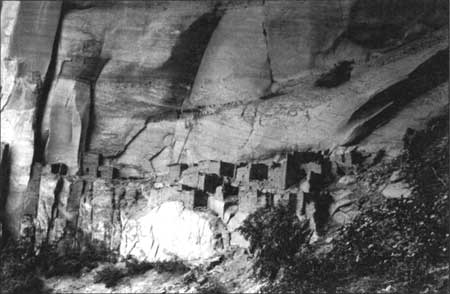

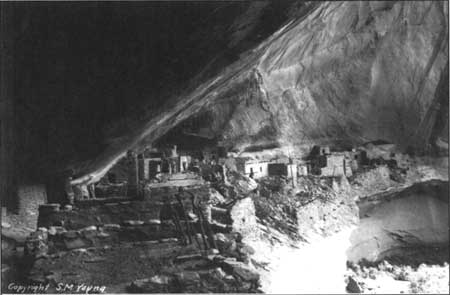

| Figure 12 Betat' akin in Navajo National Monument (Stuart M. Young Collection, NAU.PH.643.1.100, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University) | |

Gregory was forced to decline any excursion to the bridge in favor of his own work for the U.S.G.S. But one is left to wonder at Wetherill's motivations in tipping his hand to a government official six weeks prior to a planned expedition with Cummings. His antipathy toward Progressive Era bureaucrats was well documented by this time, but perhaps he was beginning to soften. Including a representative of the U.S.G.S. on the inevitable trip in August would have lent an air of official sanction to the endeavor. Wetherill knew the value of including the government and the costs of trying to exclude them. This conciliatory gesture to government authority goes a long way toward explaining Wetherill's later attempts to appease William Douglass and his eventual efforts to include Douglass in the expedition to the bridge.

| |

| Figure 13 Keet Seel in Navajo National Monument (Stuart M. Young Collection, NAU.PH.643.1.76, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University) | |

William Douglass was facing many issues related to Byron Cummings in August 1909. While in Utah to resurvey the newly created Navajo National Monument (NM). Douglass learned through others that Cummings and his party were excavating and collecting inside the boundaries of the new monument. Being the regulatory hawk that he was, Douglass was more than a little perturbed. He knew that Cummings was operating under a permit issued to Edgar L. Hewett, director of research for the Archeological Institute of America. The fact that Hewett was not present on the dig left Cummings in technical violation of the Antiquities Act. [100] Douglass's disposition was evident in his correspondence. Writing to Dr. Walter Hough of the National Museum, he said:

The expected has happened! I learn here that Prof. Hewett and Prof. Cummings went into the reserved ruins about six weeks ago . . . I fear they are excavating. If any permit was issued to them I feel certain it was done under a misunderstanding as to where they intended to work. I have just wired and written the General Land Office for authority to stop the work and prevent the removal of any archaeological remains.

P.S. Since writing the foregoing I have just seen Mr. Wetherill. He says that the GLO issued the permit to Prof. Hewett . . . He is not in the field now and Prof. Cummings is doing the work. He has obtained a very remarkable collection and unless stopped it will land in the museum of the University of Utah. [101]

| |

| Figure 14 Inscription House in Navajo National Monument (Stuart M. Young Collection, NAU.PH.643.1.59, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University) | |

Douglass informed Wetherill of his intention to stop Cummings' work at Navajo NM and to annul Hewett's permit. For Douglass, there was no room for pot-hunting in protected space. He saw little difference between pot-hunting and the work Cummings was engaged in. Wetherill rode back to Oljeto and then to Tsegi Canyon to give Cummings the bad news. [102] Before ever meeting one another, Cummings and Douglass were at odds. Cummings began to perceive Douglass as unreasonable and ill informed. Douglass already viewed Cummings as no better than Richard Wetherill.

John Wetherill tried to play the part of peacemaker. He knew that no good could come from a rivalry between federal bureaucracy and paying clients. Wetherill had a vested interest in the happiness of both parties and had more to lose than anyone if a war erupted over regulations. [103] When Wetherill arrived in Tsegi Canyon, he brought with him some mail for Cummings. A letter from friends in Bluff told that Douglass was attempting to cancel Hewett's permit and intended to confiscate any artifacts collected by Cummings. Douglass was also on his way to Oljeto to mount an expedition to the bridge. Wetherill was now in a difficult position. He had not informed Cummings of his meeting with Douglass the previous December or of his passing on knowledge of the bridge to Herbert Gregory. Wetherill knew that if they left for Navajo Mountain immediately they could beat Douglass to the trail and the bridge by four or five days. Wetherill kept his misgivings to himself and advised Cummings that they should strike out for the rock rainbow. Cummings decided that the party should return to Oljeto and wait for Douglass's party and attempt to iron out any difficulties with the GLO. Cummings had no reservations about joining forces with Douglass in an attempt to find Rainbow Bridge. After all, Cummings' primary concern was his excavation in Tsegi Canyon. Rainbow Bridge had waited all summer and could wait a few more days.

Byron Cummings' Utah Archeological Expedition consisted of Stuart Young, Neil M. Judd (Cummings' nephew), Donald Beauregard, and Cummings' youngest son Malcolm. That summer the group located two very important sites: Keet Seel and Inscription House. Wetherill already knew of Keet Seel from his brother Richard but no academic excavation or cataloguing took place before Cummings arrived. In July, Wetherill led Cummings to another set of dwellings forty miles west of Keet Seel, near Nitsin Canyon. After feasting with a Navajo named Pinieten (Hosteen Jones), Cummings was guided to a small dwelling nearby. The site was a cave pueblo of about thirty rooms that sat in a shallow cave on the southwest side of the canyon. The Wetherill's children, Ben and Ida, were with the party during this trip, as was Malcolm Cummings. Youthful curiosity led the children to explore the various rooms of the site. They removed some debris from one of the walls in a small room and discovered writing on the wall. The words appeared to the group as 1661 Anno Domini. Interpreted as the markings of some early, unrecorded Spanish expedition, Cummings named the site Inscription House. The group made a cursory survey of the area and returned to Keet Seel. [104] It was after this side journey that Wetherill returned to Oljeto and discovered that Douglass was making plans to shut down the Utah Archeological Expedition. Failing to make peace with Douglass in Bluff, Wetherill returned to Tsegi and tried to convince Cummings to head directly to the bridge. As mentioned previously, Cummings would have none of it and looked forward to confronting Douglass.

Soon after departing for Oljeto on August 7 or 8, Cummings and his group made one unscheduled stop. John Wetherill had heard from Navajos in the area of another dwelling, perhaps larger than Keet Seel. They stopped at the hogan of Nedi Cloey, whose wife addressed Louisa Wetherill. Cloey's wife learned through conversation that the group was searching for dwellings of the Old Ones. She told Louisa about a large dwelling up a side canyon that her children had found while herding sheep. Cummings gave Cloey's son-in-law, Clatsozen Benully, five dollars to guide them into the canyon. Two miles away, in a cave-like overhang at the end of an unnamed box canyon, stood Betat' akin (Hillside House). Betat' akin consisted of more than 150 rooms, with artifacts and pottery sherds scattered throughout. Because of their pressing commitments in Oljeto, Cummings and the group only stayed a little over an hour. Before leaving, however, Stuart Young took a memorable series of photographs that captured Betat' akin in an undisturbed state. [105] In this renewed framework of discovery and excitement, John Wetherill, Byron Cummings, and the Utah Archeological Expedition (UAE) returned to Oljeto and their appointment with William B. Douglass.

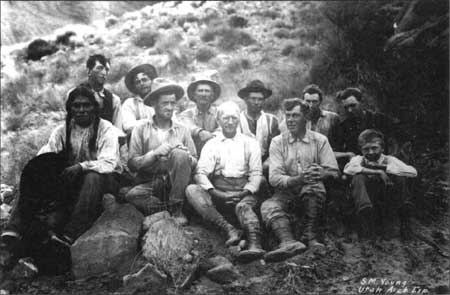

The party arrived at Oljeto on or about the evening of August 8 or August 9. William Douglass was nowhere to be found. Cummings insisted on waiting for Douglass to try and secure the UAE's claim in Tsegi Canyon. The collections they had made needed to be protected from confiscation. Two days later, in the late afternoon of August 10, Douglass arrived at the trading post. [106] His party consisted of John R. English, F. Jean Rogerson, Daniel Perkins, John Keenan, and Mike's Boy. Wetherill and Cummings had already spent most of the morning getting the party ready for an after-dinner departure. Inquiring about the controversy over their permits, Cummings later wrote:

Mr. Douglass was very noncommittal about what he had been doing or trying to do. He was very condescending toward our party, said he was going to find the big arch he had heard about, that his Pahute [sic] guide, Mike's Boy knew the country, had been to the bridge, and that we might go along if we wanted to. [107]

Regardless of the friction, the two groups joined forces and an overt confrontation never materialized. The combined expedition left within the hour and camped the first night on Hoskininni Mesa. Wetherill had already sent word to Nasja Begay, his Paiute guide, to meet the party at the Begay family farm. [108]

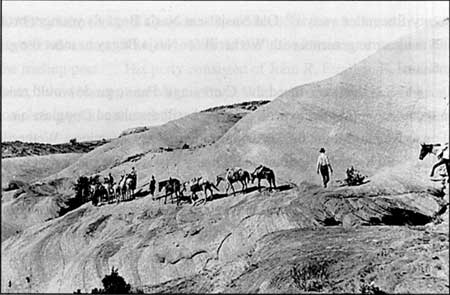

The morning of August 11 came early to everyone. The twelve-member team began traveling by dawn, heading north along Copper Canyon and toward the San Juan River. At the San Juan they turned briefly west and crossed Nokai Creek, where they made camp on the second night. On August 12, Wetherill led the tiring men up and onto Paiute Mesa. The trail was "long and dangerous" according to Neil M. Judd. [109] After crossing Paiute Mesa in the blistering heat, the trail led down Paiute Canyon and into the green river valley of Old Nasja's farm. As mentioned earlier, Cummings and Wetherill had arranged to meet Nasja Begay at his family's farm. Arriving at the farm, Begay's father, Old Nasja, informed the group that his son had tired of waiting for Wetherill and had gone to check on the family's sheep some twenty-five miles away. [110] Old Nasja sent Nasja Begay's younger brother to the sheep camp and made arrangements with Wetherill for Nasja Begay to meet the group north of Navajo Mountain.

Douglass was less than convinced that Cummings' Paiute guide would reach them in time or that he would even find the expedition. Wetherill dismissed Douglass's complaints and continued on to Navajo Mountain. Tensions mounted as Cummings, Wetherill, and Judd all noted that Mike's Boy seemed hesitant about many issues as the party progressed. He worried that untrained horses would not survive the journey, about the supply of food, and even the lack of a discernable trail. Douglass never mentioned any of these trepidations in correspondence related to finding the bridge. In any event, fearful or not, the group traveled up to the Rainbow Plateau, crossing Paiute and Desha Creek. They camped that night on the shores of Beaver Creek. [111]

Breaking camp on the fourth day the expedition made its way across vast slick rock, riding or walking up and down numerous precipices. The horses were tired, as were each of the riders. There was no obvious trail to follow and the journey was marked by men leading horses much of the way. The most daunting task of that day was locating a way around Bald Rock Canyon. Wetherill led the group down-canyon, not finding a route across until nearly the San Juan River. Once across, they had to traverse back up the west side of the canyon and resume the trail as best they could. After Bald Rock, Wetherill still had to locate a ford through Nasja Creek. Known today as the Hoskininni Steps, the expedition crossed along a set of divots pecked into the rock by some earlier travelers. The trail was so steep that one horse tumbled to the bottom of the grade. Though there were no critical injuries to any of the party, the psychological toll on every member was evident. The group finally pulled into camp in what is now called Surprise Valley. The area was well suited to their immediate needs, offering water, feed, and rest to men and horses alike. [112]

| |

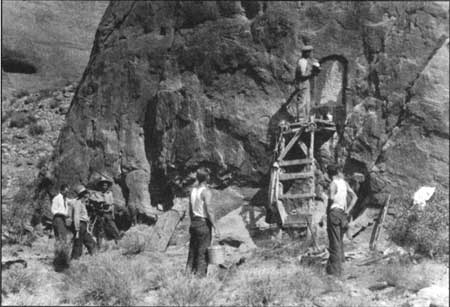

| Figure 15 Expedition party and horses west of Navajo Mountain, en route to Rainbow Bridge, August 13, 1909 (Courtesy of the National Archives, NWDNS-NJ-NJ-302. Photo by Neil Judd) | |

On that last night, most of the members of the expedition were exhausted and frustrated. Mike's Boy seemed more and more anxious about his ability to find the great rock rainbow. Judd, Cummings, and Wetherill all wrote later that Mike's Boy confided in them that he had never been to the bridge but only heard of it from other Paiutes. [113] This observation was later denied by members of Douglass's team. Many of the expedition members were not completely sure of what might happen next. Then came the unexpected. At approximately 10:00 p.m.. Nasja Begay rode into camp. It was "one of those unlikely but fortuitous miracles" that sometimes occur at key moments in history. [114] There was no telling how he managed to find the camp in the dark, especially given the secluded location of Surprise Valley. The entire team was elated at Begay's presence. He agreed to lead the group to the bridge the following day and lead them back to Oljeto for the sum of three silver dollars per day. [115]

The last day of exploring was short and sweet. Expedition members, bolstered by the arrival of Nasja Begay, moved lively over the trail. Spirits were high as the riders ascended Hellgate, a ravine that exited Surprise Valley. As the day progressed, Cummings and Douglass were certain they would reach the bridge. They followed the trail through the southern end of Oak Creek (near the base of Navajo Mountain) and then north along Bridge Creek. Nasja Begay indicated that the bridge was very close. At this point in the historical record, participant recollections of the journey took on a less professional tone. No doubt the rigors of the trek took their toll on everyone, including professionals like Wetherill, Cummings, and Judd. The UAE members recalled the day with gritted teeth. Judd later wrote:

Throughout the last day's travel, with the big bridge reported not far ahead, Mr. Douglass exhibited the uncontrolled enthusiasm of the amateur explorer and he was so disregardful of possible danger to the other members of the party as to arouse the disgust of all. Seemingly impelled by the hopes of the old conquistadores; apparently without consideration for his companions, he repeatedly crowded the other riders from the narrow trail as he forced his tired horse to the front. Douglass was the only member of the expedition engaged in this wild race; time and again he turned back from ledges he had unwisely followed, only to rush forward again at the first opportunity. [116]

Even Cummings contended that Douglass was in the midst of jockeying for position so as to ensure his claim to being the first white man to see Rainbow Bridge. Cummings later remembered:

After we negotiated the difficult Red Bud Pass [on the eastern side of Bridge Creek], Mr. Douglass, Mr. Wetherill, Noscha Begay [sic] and I halted in the shade of a cliff to let the packs catch up with us. Mr. Douglass turned to me and said, "I should think you would go back and look after that boy of yours. I have a boy a little older than yours, but I think too much of him to bring him into a country like this. If you thought anything of your boy, you'd stay with him and look after him." It was soon evident why Mr. Douglass was anxious that I fall behind with the packs. [117]

William Douglass recalled the day with less vitriol than his contemporaries. He wrote in his report to the GLO:

On the morning of the last day's travel, when we were told by the Indian guides that the bridge would be reached by noon, the excitement became intense. A spirit of rivalry developed between Prof. Cummings and myself as to who should first reach the bridge. The first three places of the single file line were of necessity conceded to the three guides. For three hours we rode an uncertain race, taking risks of horsemanship neither would ordinarily think of taking, the lead varying as one or the other secured the advantage over the tortuous and difficult trail. [118]

A description of the moments before rounding the bend that revealed Rainbow Bridge is gleaned from a general consensus of participant reports. It was true that Douglass was in the lead. Whether or not he saw the bridge before the others cannot be determined. Wetherill, Judd, and Cummings all remembered that when they rounded the last bend and sighted Rainbow Bridge, they stopped to admire the span. They yelled to Douglass to get him to return to their position. Yelling was necessary because William Douglass was extremely hard of hearing. [119] This does not indicate conclusively that Douglass failed to sight the bridge as he rounded the same corner at which Cummings and Wetherill chose to stop. What is certain is that Cummings, based on this observation, claimed the honor for himself as the first white man to see Rainbow Bridge. The date was August 14, 1909.

After pausing at the bend, Wetherill and Cummings dismounted and began to lead their horses toward the bridge. Douglass, on the other hand, remained mounted and spurred his horse toward the rock rainbow. Various participants wrote differing versions of what words passed between Wetherill and Cummings. Cummings contended he was satisfied with having seen the bridge first. [120] Wetherill claimed that Cummings thought it would be rude to race Douglass to the bridge and that he (Wetherill) replied, "Then I'll be rude." [121] At the sight of Douglass galloping away Wetherill remounted, spurred his horse, and raced past Douglass. Wetherill stood alone under the expanse of Rainbow Bridge for a brief moment before the other members of the expedition arrived. [122] The only reports that contradicted this version all came from William Douglass. In 1919, Douglass wrote to NPS Director Stephen Mather:

Instructions to visit the bridge were received from the General Land Office, dated Oct. 20, 1908. in compliance with which, an effort was made to reach it that year. It was then that Mr. Wetherill learned of the bridge and its approximate location. In 1909, he was employed by Prof. Cummings . . . and told Cummings of the bridge. They planned to beat me to it, but failed, as I reached it before Cummings. I made no effort to get in front of Wetherill any more than I did to get in front of the Indians. [123]

This version of the story conflicted with Douglass's original report from 1909 and the description of the race that developed between he and Cummings. More important than the issue of who saw Rainbow Bridge first, the 1919 letter revealed Douglass's belief that Wetherill learned of Rainbow Bridge from him. When Douglass went to Oljeto in the fall of 1908, Wetherill tried to convince him that the bridge did not exist. Wetherill disclaimed any knowledge of any colossal rock rainbow. Douglass went to his grave believing that he himself was the source of Wetherill's knowledge about Rainbow Bridge. Wetherill's subterfuge was certainly the root of Douglass's later conviction that Mike's Boy deserved all the credit for bringing Rainbow Bridge out of myth and into reality.

After the historic posturing concluded, the expedition made camp below the bridge. Horses were set loose to graze and various members of the party wandered below the bridge's span. Douglass and his team set about measuring Rainbow Bridge. Using two steel tapes they had carried with them, the height was measured at 309 feet and the span at 278 feet. This was by far the largest arch in the known world and the team was duly impressed. Cummings, Judd, and Donald Beauregard headed down Bridge Canyon to locate the creek's confluence. Cummings reported a slot canyon that was narrow enough to touch both walls with his fingertips. Cummings and the others returned near midnight. Meanwhile, Wetherill located a route to the top of the bridge by means of climbing above the bridge via the west buttress and then lowering himself onto the arch with a rope. [124]

After measuring the bridge, Douglass and his team stayed a few more days to survey the boundaries of what became Rainbow Bridge NM. Douglass laid out a 160-acre square centered on the bridge. Except for minor changes made later to the corner markers, Douglass's original boundaries remain intact to the present day. After the boundary survey, they returned across the southern mesas to Tsegi Canyon to survey Betat' akin and Keet Seel. Cummings began his return to Salt Lake City the day after finding Rainbow Bridge; he had to be back in time for Fall semester at the University of Utah.

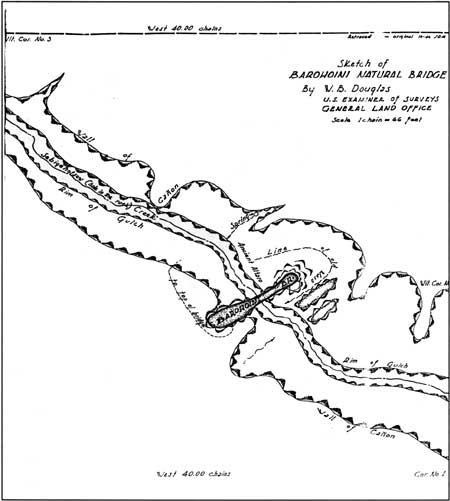

Douglass also conceived of a name for Rainbow Bridge. In his 1910 report to the GLO regarding the expedition, Douglass claimed that his guides spoke a Navajo word, nonnezoshi, meaning "hole in the rock." Seeking a fitting tribute to the Paiutes who brought knowledge of the bridge to the English speaking world, he claimed he asked one of the guides for the Paiute word for rainbow. Douglass claimed the reply they offered was barahoine. Douglass made a topographic sketch of the bridge that revealed his desire for the Paiute name. In fact, the Navajo word for Rainbow Bridge is tsé naa Na'ni'ahi, which translates as "rock arch." [125]

| |

| Figure 16 W.B. Douglass map of Rainbow Bridge, 1909 (Courtesy of Glen Canyon NRA, Interpretation Files) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) | |

Douglass left Bridge Canyon on August 17. Neil Judd and Dogeye Begay, Wetherill's wrangler, led Douglass and his team to Tsegi Canyon. Douglass was in Tsegi Canyon by August 21, completed his survey of Navajo NM by early September, and returned to the GLO office in Cortez by September 11. The excitement over Rainbow Bridge spread quickly. Various regional newspapers carried word of the "discovery" in editions as early as September 2. In October, Donald Beauregard wrote his version of the adventure for the Salt Lake City's Deseret News. The first major report of the expedition came in the February 1910 issue of National Geographic. It was authored by Byron Cummings and included photographs taken by Stuart Young. There was little argument over the natural and scientific importance came of Rainbow Bridge. The articles that after the bridge's "discovery" all pointed to its awe-inspiring physical beauty as well as its unique geologic significance. In his report to the GLO, William Douglass urged that the bridge be designated a national monument in order that it be protected from various threats. Douglass' efforts were bolstered by the attention the bridge received in the popular press. Based on the many considerations extant at the time, Rainbow Bridge became part of the national park system. On May 30, 1910, President William Howard Taft designated Rainbow Bridge National Monument. In his proclamation, President Taft declared that the bridge possessed great scientific interest and was an example of "eccentric stream erosion." Utilizing the boundaries surveyed by William Douglass, the proclamation set aside 160 acres around Rainbow Bridge. [126]

| |

| Figure 17 Rainbow Bridge, August 13, 1909 (Stuart M. Young Collection, NAU.PH.643.243 Cline Library, Northern Arizona University) | |

Over the course of the next forty years, participants of the first successful expedition to Rainbow Bridge jockeyed over the credit for finding the bridge, indicting each other's integrity in the process. For his part, William Douglass remained steadfast in his assertion that he sighted the bridge before Cummings, that Mike's Boy knew of the bridge before anyone else and shared that information with Douglass long before Wetherill or Cummings had knowledge, and that Mike's Boy led the joint expedition to its goal. For unknown reasons, Douglass even went so far as to claim credit for locating and naming Inscription House. In the same 1919 letter to Mather cited earlier, Douglass also wrote:

The Natural Bridges National Monument and the Navajo National Monument were both made on my recommendation and based on my surveys. The latter was first called to the attention of the Interior Department by me, and several of its ruins are of my discovery, including the discovery of the inscriptions, which resulted in my naming that ruin "Inscription House." [127]

The world may never know what inspired Douglass to claim credit for discoveries he clearly had no part in making. But in his official report to the GLO concerning Rainbow Bridge, Douglass mitigated Wetherill's role to nothing more than "packer" and took the position that Byron Cummings and his team had joined Douglass and the government party. Nasja Begay was never mentioned in Douglass's notes or his reports. Douglass noted that he and his assistants were the first human beings to walk atop the bridge. The members of the Utah Archeological Expedition rallied around Cummings and against Douglass's obvious disinformation.

| |

| Figure 18 Expedition party seated below Rainbow Bridge, August 13, 1909. Back row, left to right: John English, Dan Perkins, Jack Keenan, Francis Jean Rogerson, Neil M. Judd, Donald Beauregard. Front row, left to right: Jim Mike (Mike's Boy), John Wetherill, Byron Cummings, William Boone Douglass, Malcolm Cummings (Stuart M. Young Collection, NAU.PH.643.2.9 Cline Library, Northern Arizona University) | |

The official government history of the "discovery" of Rainbow Bridge was drawn from Douglass's report to the GLO and remained true to that version of the story for many years. Douglass refuted various deviations from his version that appeared sporadically in the government press. [128] For the most part, the members of the first expedition had individual versions of what happened and of who knew what and when. Cummings published his version in February 1910. It was totally innocuous in its description. Cummings mused that "not even Hoskininni seems to have penetrated as far as the Nonnezoshi [Rainbow Bridge]. The members of the Utah Archeological Expedition and of [the] surveying party of the U.S. General Land Office, who visited the bridge together August 14, 1909, are evidently the first white men to have seen this greatest of nature's stone bridges." [129] There was no doubt in this publication that Cummings had divorced himself from any controversy or disagreement over credit for finding the bridge. Though he did publish the bridge's measurements without crediting the GLO, there was nothing in his article that suggested he made the measurements himself. Douglass's contention that Cummings "stole" the measurements and published them as his own was drastically overstated. One obvious fact remained true: Cummings acknowledged the participation of the GLO in finding Rainbow Bridge while Douglass all but omitted the UAE from his own official report. There was nothing in Cummings' early publication of the Rainbow Bridge expedition which suggested any attempt to either credit himself with the discovery or to exclude Douglass from the story.

Eventually, Sterling Yard, director of the National Parks Association (NPA), solicited Neil Judd's version of the events. Yard was instrumental to the Park Service as a publicist during large scale advertising and public relations campaigns. The Park Service, through the NPA, was trying to structure its image and its history for the public. [130] The details of every monument's history were important to this pursuit. Fortunately for Judd, Yard did not subscribe to the official line penned by Douglass. Judd wrote his brief narrative on October 30, 1919. The report disparaged Mike's Boy as a liar and Douglass as an amateur. Judd ascribed the credit for finding the bridge to Nasja Begay and his father, Old Nasja. [131] Wetherill chimed into the debate in 1924. He decided that there should be a commemorative plaque erected at the bridge honoring Nasja Begay as the real discoverer of Rainbow Bridge. To this end he wrote numerous letters to the National Park Service. Wetherill, in the course of this correspondence, took his jabs at Douglass and Mike's Boy. He wrote, "it was very evident that Jim [Mike's Boy] did not know the trail. I do not feel that Jim is entitled to any of the credit." [132] Wetherill also excluded any information relating to Douglass's aborted attempt to find the bridge in the fall of 1908 or of the disinformation he passed on to Douglass. Wetherill was not seeking credit for himself but rather his friend and guide, Nasja Begay. Cummings also wrote to the Park Service on this issue, verifying most of Wetherill's claims and the singular importance of Nasja Begay to finding Rainbow Bridge. [133] For the most part, the members of the first expedition were honorable explorers or government servants. Despite their differences, they all agreed that no white man would have found the bridge without one or both of the Paiute guides. To that end they all lobbied for a commemorative plaque which acknowledged this most basic fact.

John Wetherill began his attempts to honor Nasja Begay in 1924. Unfortunately, Begay had contracted influenza in 1918 and died as a result. Wetherill felt compelled to secure his friend's place in history and bronze as "the Indian who guided the first party to the Bridge." The initial problem was that the Park Service assumed Wetherill was talking about Mike's Boy, the Indian guide the Park Service knew from Douglass's official reports. This was NPS Director Mather's assumption in his reply to Wetherill a year later. This naturally reignited the whole debate among the original participants over which Paiute guide did what and what each expedition member knew and when they knew it. John Wetherill, Byron Cummings, and Neil Judd all wrote to Director Mather regarding their individual participation in the expedition and the role of their guide in finding Rainbow Bridge. Their efforts to ensure that Nasja Begay be remembered as the Paiute who found the bridge were admirable. For its part, the Park Service was dealing with a great deal of mixed information. Given the numerous and inconsistent versions of the "discovery" story, the Park Service personnel assigned to verify the historic record were slightly confused. Even Director Mather, for example, was unsure of the Paiute guide's identity in early correspondence with Wetherill. Based on the intense interest in honoring the expedition's guide, Dan Hull, chief landscape engineer for the Park Service, made plans in March 1924 for a bronze plaque bearing the likeness of Nasja Begay and a brief narrative of the "discovery." The plaque was to be placed very near the base of the bridge itself, in plain view of any future visitors. [134]

Plans for the commemorative plaque continued through 1924 with design sketches and copy edits passing between various members of the Park Service. [135] But in July 1925, the official story still had not changed. A press release and information bulletin was in preparation to assist the growing number of visitors to Rainbow Bridge. That press circular identified Mike's Boy as the only Paiute guide on the expedition and described Cummings and Wetherill as ancillary to the whole event. By 1927 the "official" story was breaking down. Various public inquiries about who located Rainbow Bridge were answered by accounts that included Cummings, Wetherill, and Begay. Assistant Director A.E. Demaray, as well as Associate Director Arno B. Cammerer and Director Mather, were slowly but carefully gathering facts about the first expedition and relating those facts to other Park Service personnel. Based on the more complete story, Mather authorized mounting the commemorative plaque in September 1927. [136] The original plaque read "To Commemorate the Piute [sic] Nasjah Begay Who First Guided The White Man To Nonnezoshi August 1909. [137] The real irony came with the event's press coverage. In newspaper stories which followed the plaque hanging ceremony, columnists credited John Wetherill as the first white man to see Rainbow Bridge, giving only cursory mention to the other members of the party.

The other story of note in 1927 was Neil M. Judd's published account of the expedition in the National Parks Bulletin. [138] Judd correctly identified the caveat that marked the controversy over who first located Rainbow Bridge. He wrote:

Who actually discovered Nonnezoshe? Nobody knows. Some Indian way back in that pre-Colombian past when man romped and roamed widely over this continent of ours but left no written record to prove it. Some Indian was the real discoverer. But we whites have a conceit all our own which frequently tempts us to ignore the achievements of those of a different hue. A thing clothed in the traditions of a thousand years remains unknown until we ourselves have seen and recorded [it]. [139]

Rainbow Bridge was not discovered by Douglass, Cummings, Wetherill, or anyone else in 1909. It was located and mapped and then introduced to the English speaking world as a wonder to behold. It was exceptionally humble for Judd to couch his entire article in the framework of being last to the bridge. While Judd still clung to the belief that Cummings was the first white man to see the bridge, he did present a valuable statement about the biases of history and the way fortune favors the literate Eventually the whole story of August 1909 was told to the world. The plaque commemorating Nasja Begay's role in the first expedition hung silently on a rock near the bridge for fifty years. But in the fall of 1973, Empire Magazine, a weekly supplement to The Denver Post newspaper, published an article that detailed Mike's Boy's (known by this time as Jim Mike) part in the first expedition. Zeke Scher, a writer for Empire, obtained copies of William Douglass's account of the expedition and wrote an article to vindicate Jim Mike. Mike never told his story to the world, perhaps assuming Douglass would take care of the history. It is possible he never knew about the plaque honoring Nasja Begay. Jim Mike did not return to Rainbow Bridge until 1974.

In June 1974, Jim Mike was 104 years old. He was alert and active but in no condition to trek to Rainbow Bridge. Fortunately for Jim, the inundation of Lake Powell had made it possible by this time to access the bridge via boat. He would not have to hike to have his place in history commemorated. The Park Service planned a ceremony to honor Jim Mike for his part in the Cummings/Douglass expedition and for his contribution to making the new monument possible. The ceremony took place June 18, 1974. At the ceremony, NPS Regional Director Lynn Thompson presented Mike with a new robe and $50.00—a guide fee that the Park Service felt Mike was owed for his services in 1909. It was a fitting tribute that Mike obviously appreciated; however, there was still no plaque honoring Jim Mike as one of the original guides. Another article appeared in Empire in 1974. The second article retold of Mike's role in 1909 and detailed the 1974 ceremony. Within a year, someone clandestinely removed the plaque honoring Nasja Begay and threw it into the waters of Lake Powell just beneath the bridge. In the early 1980s the Park Service remounted the Nasja Begay plaque in its original location. They also placed a smaller plaque just below Begay's which recognized Mike's part in the 1909 expedition; unfortunately, he did not get the chance to see his name immortalized in bronze. On September 28, 1977, Jim Mike died of natural causes. He was 107 years old. [140]

| |

| Figure 19 Mounting the plaque, 1927 (Courtesy of Glen Canyon NRA, Interpretation Files. Photo by Raymond Armsby) | |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

rabr/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 31-Aug-2016