|

Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway

Time and the River: A History of the Saint Croix A Historic Resource Study of the Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway |

|

CHAPTER 1:

Valley of Plenty, River of Conflict

Moving almost silently through the forest Little Crow approached the place where he had set one of his steel beaver traps. Through the morning mist the Mdewakanton Sioux leader saw that someone had preceded him to the site. The stranger lifted the trap, heavy with a fine, fresh beaver carcass, and was about to remove the valuable catch when he suddenly looked up to see Little Crow. With "a loaded rifle in his hands" Little Crow "stood maturely surveying him." The stranger was not a Sioux, or as Little Crow himself would have referred to his people, a Dakota. The man was dressed in the manner of the Chippewa. For two generations the Dakota and the Chippewa had been at war for control of the Upper Mississippi and St. Croix River valleys. This Chippewa had been caught not only deep in Dakota Territory, but also in the act of committing the worst type of thievery, robbing another hunter's trap. As an act of war and self-defense, Little Crow "would have been justified in killing him on the spot, and the thief looked for nothing else, on finding himself detected." [1]

"Take no alarm at my approach," said Little Crow. Instead of raising his rifle, the Dakota chief spoke gently. "I only come to present to you the trap of which I see you stand in need. You are entirely welcome to it." The wary Chippewa was further taken back when Little Crow held out his rifle. "Take my gun also, as I perceive you have none of your own." The chief capped this unlikely encounter by offering the stunned Chippewa a healthy piece of advice, "depart. . .to the land of your countrymen, but linger not here, lest some of my young men who are panting for the blood of their enemies, should discover your foot steps in our country, and fall on you." With that, Little Crow turned his back on the rearmed enemy and traced his steps back to his village.

The story of Little Crow's gesture was recorded by the United States Indian Agent Henry Rowe Schoolcraft in his narrative of an 1820 journey to the Upper Mississippi country. Schoolcraft included the story because it illustrated the contradictory perception held by European Americans of the Dakota people. Lieutenant Zebulon M. Pike who had visited Little Crow's village in 1805 had described the Dakota as "the most warlike and independent nation of Indians within the boundaries of the United States, their every passion being subservient to that of war." Yet Schoolcraft also noted that they were "a brave, spirited, and generous people." Little Crow's gesture was magnanimous, but it also was an exercise of supreme self-confidence by a warrior whose mastery over his opponent did not depend upon his ownership of a mere firearm. Through his exaggerated generosity, Little Crow counted a notable coup. Through Little Crow's action the Chippewa thief was reduced in status from that of an invader, to that of a mere beggar. The encounter also underscores an important historical point. For the Dakota and the Chippewa, the most important event on the St. Croix between the mid-eighteenth century and mid-nineteenth century, was not the expansion of the fur trade nor the arrival of European-American settlers, but a terrible and persistent intertribal war. It was the interests and actions of the Indians, not those of a handful of fur traders or Indian agents that shaped the early history of the valley. [2]

Figure 1. A Chippewa Family, c. 1821. Courtesy of the

National Archives of Canada.

The Dakota and Their Neighbors

Dakota's ability as warriors, their generosity, and their pride as a nation were all defining characteristics of the first historic inhabitants of the St. Croix valley. The Dakota could afford to be generous because they occupied one of the largest and richest regions of the North American interior. The early French fur trader Nicholas Perrot called it "a happy land, on account of the great numbers of animals of all kinds that they have about them, and the grains, fruits, and roots which the soil there produces in abundance." The St. Croix was the northeastern border of a Dakota homeland that extended along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, from the mouth of the Wisconsin River on the south to the headwater lakes in the north, and along the Minnesota River westward to the Great Plains. Not just its vast extent made this homeland rich. The diversity of landscape at the disposal of the Dakota offered a cornucopia of resources to the nation's hunters and gatherers. The Dakota lands straddled the northern woodlands and transitional prairie ecosystems and were united by rich riverine corridors and pockmarked by countless lacustrine clusters. Only the long hard winters of north central America tempered the possibilities of an otherwise lavish and diverse environment. [3]

"Places are defined," observed historian Elliott West, "in part when people infuse them with imagination." The Upper Mississippi landscape found by European American explorers such as Pike and Schoolcraft was shaped by the choices made by its Dakota inhabitants. Other Indian peoples, such as the Shawnee or the Huron, would have looked upon the rich bottom lands along the Mississippi and envisioned fields of maize, or later white settlers saw commercial lumber in white pine thickly arrayed in ranks along the margins of the northern lakes. The Dakota, however, arranged their homeland as a grand hunting preserve. Like most Native American people's of the Upper Midwest the Sioux structured their lives around a seasonal subsistence cycle. In the case of the Mdewakantonwan this cycle was based on hunting, not the gardening of maize or beans that played an important role in the lives of the Algonkian Indians who dominated the Great Lakes region. Dakota men were hunters and warriors. Fittingly they approached hunting as they approached war, cooperating with other Dakota to overwhelm their prey yet always alert to the possibilities of individual recognition. [4]

The Dakota began their year amid the thousand lakes of northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. Large lakes of the St. Croix valley, such as Chisago, Pokegama, and Upper St. Croix became the sites of villages of one hundred or more deerskin lodges. Men were active throughout the winter hunting white-tailed deer. Generally able to structure their hunts to suit their palates, the Dakota hunters would alternate the taking of deer with the hunting of winter bears. In winter deer and elk were a bit too lean and therefore dry when cooked to suit the taste of the Dakota. Bear on the other hand were heavy with fat in the winter and when taken and rendered added savor to other meat. Women prepared meals and treated hides. During the late February and March days, when the winter sun formed a crust of ice upon the deep snowdrifts of the forest, the Dakota hunters stalked herds of elk. These graceful grazing animals favored the open prairies during most of the year but retreated to the fringes of the forest when winter was at its worst. Moving swiftly over the frozen snow with their snowshoes the Dakota could take large numbers of elk, as they broke through the surface snow and struggled in the drifts. [5]

The proud hunters were greeted with the cry "Kous! Kous!" as young boys saw the men return to the village burdened with heavy loads of meat. Soon every lodge was empty as the entire community, young and old, rushed out to honor the hunters. The shouts continued to rent the evening air until the men laid down the meat at the door of their lodges. A successful late winter elk hunt became the occasion for a great round of feasting among the Dakota lodges. A hunter established his status in part by forcing upon his guests more food than could be consumed. Eating to the point of nausea was the mark of a true Dakota. When elk hunting failed, as it occasionally did because of a lack of snow, the Dakota relied on fish taken in the adjacent lakes. Like true hunters the Dakota favored spearing fish to the use of nets or hooks, and if their efforts failed or yielded meager results, they accepted a shortage of food as a natural part of the season. Wild plants helped to bridge the rare seasons of want and the more common seasons of plenty. In 1767 Jonathan Carver witnessed the Dakota chewing the soft, inner fibers of "a shrub," perhaps the red willow, which he said tasted "not unlike the turnip." [6]

When the sap of the maple tree began to run, in March or April, the specter of a season of want disappeared. Women took the lead organizing the work of tapping maple trees, gathering sap, and boiling the liquid into sugar. Besides a few old men or boys who might help tend the fires, the sugar camps were composed entirely of women. Most of the men were off trapping or hunting waterfowl. Women united by kinship ties often came together to share the work and fun of making sugar. The sugar camp might be occupied for as long as a month and as many as one hundred trees could be tapped. The hardest part of the sugar making was the preparation of wooden troughs used for boiling. Although the bottoms of these hallowed logs were smeared with mud to retard their burning, exposure to the direct flames of the rendering fires meant that troughs had to be continuously replaced. Such work was well-rewarded when the finished sugar was gathered in birch bark containers and the women of the family held feasts in which bark pans of sugar were passed around for all to enjoy. Amid the laughter and stories that were shared, the women and children joined in jokes and dares. A frequent dare was to see who could drink the most of what one anthropologist called "a revolting concoction," liquid tallow. The tallow was used in small amounts to help process the sugar. Around the sugar campfire some women responded to their challengers by drinking cupfuls. Then everyone awaited the results on the winner, who often became sick or sleepy. [7]

In summer whole villages of Dakota took to their canoes and journeyed down the St. Croix to its junction with the Mississippi. Amid the hills and river terrace prairies just west of the great river roamed herds of buffalo. Before the Europeans came the buffalo ranged throughout the domain of the Dakota and more than any other reason accounted for the abundance that normally marked the life of the Mdewakantonwan Sioux. The Dakota held their summer buffalo hunts on both banks of the St. Croix. Bison ranged throughout western Wisconsin and small herds were even known to graze in the marshy pine barrens of the St. Croix's headwaters region. The most popular place to hunt the buffalo, however, was on the lower St. Croix and along the Upper Mississippi. In 1680, the missionary-explorer Father Louis Hennipen accompanied the members of a village of Mille Lacs Dakota on a buffalo hunt as far south as Lake Pepin, on the Mississippi. There they killed more than 120 bison. [8]

The summer buffalo hunt was a defining cultural experience for the Dakota of the St. Croix valley. The buffalo provide the means and the rationale for the Dakota community. In contrast to many of their Algonkian neighbors who lived much of the year in small groups of only several families, the Dakota lived in villages composed of hundreds of people. The village functioned as a unit, not as a congregation of individual hunters. This discipline was established by the requirements of the buffalo hunt. "They assemble at nightfall on the eve of their departure," the fur trader Nicholas Perrot observed, "and choose among their number the man whom they consider most capable of being the director of the expedition." This master of the hunt and his adjutants assigned each man his role in the coming endeavor, scout, shooter, or as a policeman enforcing tribal discipline. Unlike the popular image of a Sioux buffalo hunt, with hunters racing over the plains on horseback, shooting their prey, the Dakota approached the hunting grounds via birch bark canoes. Upon the receipt of reports from the scouts the leader would quietly dispatch the hunters, sometimes with the use of smoke signals, who would drive the herd toward its destroyers. Hennepin witnessed two hundred men converge on a buffalo herd from opposite slopes of a large hill. The two groups of hunters "shut in the buffalo whom they killed in great confusion." Sometimes the bison could be driven by means of prairie fires over a high riverbank and dispatched in that way. The traditional technique of the Dakota buffalo hunt was a group effort leading to a massive slaughter of game. The aftermath of such a hunt, the ground packed with bleeding animals in their death throes, might strike modern readers, as it did the nineteenth century artist Paul Kane as "more painful than pleasing," but such a sentiment would have been foreign to a hunting people like the Dakota. [9]

The excitement of the hunt slowly gave way to the drudgery of processing the harvest of meat and hides. In the disciplined structure of the Dakota buffalo camp much of this work fell to the women. Some were given the task of quartering and butchering the bison. Others may have been regarded as specialists preparing hides that would become blankets, clothing, and crucial to the Dakota's mobility -- tents. The most laborious task of the women was the drying of thousands of pounds of meat. This was done over slow burning fires with heat, smoke and sun joining to preserve thin strips of buffalo for up to a year. So important was this task that the prudent hunt leader never selected a kill site far removed from a large supply of firewood. It often took weeks to properly dry and store the meat of a single large kill. [10]

A successful buffalo hunt provided the Dakota with security from want for the remainder of the year. Hunters continued to pursue game throughout the year, including buffalo. But the July hunt was purposely designed to produce not fresh meat for the moment, but an insurance policy for the rest of the year. The Mille Lacs Dakota with whom Hennepin lived in 1680 were particularly scrupulous to husband their harvest for the future. The Frenchman observed that "The women buucanned [dried] the meat in the sun, eating only the poorest, in order to carry the best to their villages, more than two hundred leagues from this great butchery." " So fundamental was this hunt to the prosperity of the Dakota that hunt leaders were given extraordinary powers to ensure that nothing or no one endangered the community endeavor. Hennepin encountered one group of Dakota celebrating an early buffalo hunt. They arrived ahead of the rest of the village and rather than wait, made a large killing on their own. The hunters of the main party were furious and destroyed the early arrival's lodges and took all of their meat. One of them explained to the priest "having gone to the buffalo-hunt before the rest, contrary to the maxims of the country, any one had the right to plunder them, because they put the buffaloes to flight before the arrival of the mass of the nation." [11]

In late summer the Dakota would return to the northern lakes. Men would hunt waterfowl and deer, while the women prepared for the vital harvest of wild rice. The rice harvest was second in importance to the buffalo for the prosperity of the Dakota. The Upper St. Croix country excelled as a habitat for the tall aquatic grass known as wild rice. Early French explorers, such as Nicholas Perrot, described the plant as "wild oats," which was actually more accurate because it is not a rice at all but an annual cereal grass. In later years the European-American fur traders labeled the St. Croix valley as the "Folle Avoine country," using the French words for wild rice to characterize the region. The dam on the St. Croix River at Gordon, Wisconsin destroyed one of the finest wild rice habitats in the region when it flooded the marshy shores of the natural river to create a large recreational lake known as the St. Croix Flowage. For generations before the dam Indian women relied on this rich stretch of river. Dakota women would sometimes seed lake or stream shores to increase their future harvests, but the majority of the wild rice crop grew naturally. Harvesting the crop so as to ensure its return the next year and processing it as a food source required considerable ingenuity and long hours of work. Women gathered the rice in a canoe in which they carefully shook the grain from the tops of the grass, often by means of a wooden stick, so as not to damage the plant. Once a canoe load was brought ashore. "The rice was then separated from the chaff by scorching it in a kettle," recalled an early Minnesota settler, "and then beating it in a mortar made by digging a circular hole in the ground and lining it with deer skin." [12]

Prior to the eighteenth century agriculture seems to have played a very small part in Dakota life. The amount of wild rice available in the homeland of the Mdewakanton Sioux assured a steady source of natural cereal. Small plots of corn were sometimes planted near village sites, but the amount was never enough for maize to serve as a sustaining element in their diet. Its role seems to have been as a source of diet variety. Similarly they would establish plots of tobacco near their villages. Most of what the Dakota desired was obtained by hunting or through the gathering of wild plants.

The final stage of the Dakota's annual subsistence cycle began in October or November, "the moon of the deer." For one or two moons the large villages would break up into smaller bands that would then cooperate in a communal hunt of white-tailed deer and occasionally elk or woodland caribou. Often they would employ tactics reminiscent of the buffalo hunt, coordinating the movement of large numbers of hunters to drive the deer toward designated shooters. Before the hunt ended in January, with a return to their large semi-permanent lakeside villages, the deer hunters often succeeded in bagging large numbers of deer. Samuel Pond, an early settler who knew the Sioux well, estimated that two Dakota bands combined to kill two thousand deer during the year. [13]

The abundance of food resources that was a manifest part of Dakota life in the St. Croix valley could give the impression, as historian Gary Anderson has observed, that their lives were "rather idyllic." But the abundance came at a cost. The toll was levied, in part, by the Dakota's frequent movement across the Upper Mississippi landscape. "They have no fixed abode," declared Pierre de Charlevoix somewhat erroneously, "but travel in great companies like the Tartars, never stopping in any place longer than they are detained by the chase." Early French geographers referred to the Dakota as the "wandering Sioux." Andre Penigault, who lived with them in 1700, described the Dakota as "toujours errante," always wandering. The French did not see that the abundance of Dakota life was based on their movement, the ability to exploit each segment of their varied homeland at its peak for hunting and gathering. Their large, semi-permanent lakeside villages were an exception to this movement, and it was while in residence in these villages that the Dakota were susceptible to a shortage of resources. Because these sites were occupied repeatedly over the years they suffered from a shortage of firewood and reduced game populations in their vicinity. It was the very young and especially the very old who bore the burden of the seasonal cycle. Those who could not keep up with the group risked the health and well being of the other family members. [14]

"Hunting is the principal occupation of the Indians," declared Jonathan Carver who lived among the Dakota during the 1760s. Typical of European observers he sneered at what he perceived as the "indolence peculiar to their nature," but did not see the contradiction when he described Dakota hunters as "active, persevering, and indefatigable." The fact was that successful hunting cultures such as the Dakota required considerable energy and sacrifice from their hunters. Bringing down an enraged buffalo or elk at close quarters with a compound bow was fraught with risk, as was the pursuit of game across a frozen boreal landscape. Dakota women also bore a heavy burden. On the move the burden was not merely metaphorical but might entail a pack and tumpline of well-over one hundred pounds.

The abundance of the Dakota excited the envy of their Indian neighbors and attracted the notice of the French. Pierre Esprit Radisson and Medard Chouart, Sieur Des Groseillers, the first Europeans to penetrate the interior of northern Wisconsin, first encountered the Sioux during the winter of 1659. Unusual climatic conditions had ruined the winter hunts of the Menominee among whom the French were staying. After being forced to eat the dogs of the village starvation gradually consumed its inmates. As the horrible winter came to a close representatives of the Dakota arrived in the village. The eight well-fed Dakota men, each accompanied by two wives bearing baskets of wild rice, strongly impressed the haggard Europeans. Without hesitation they accepted the invitation of the Dakota to visit their lands. [15]

The Dakota demonstrated considerable forbearance, even generosity toward their Algonkian neighbors to the east. But like Little Crow's decision to spare the life of a Chippewa robbing his trap, the Dakota peoples' generosity was calculated. As early as 1650 the Dakota allowed remnants of the Huron, who had been driven from their homelands near Georgian Bay by Iroquois invaders, and a small group of their Ottawa allies to settle in Dakota Territory near Lake Pepin. The Dakota were at least in part motivated by the desire to obtain French trade goods from the two tribes that had been the backbone of the early western fur trade. But Sioux generosity seems to have been misinterpreted as a sign of weakness by the Huron and Ottawa who tried to drive the Dakota away from the Mississippi. This major miscalculation of Dakota capability and intent, led to the complete expulsion of the Huron and Ottawa from Dakota lands. For the next hundred years the Dakota were intermittently at war with eastern Algonquin the Iroquois had driven tribes, many of whom, like the Huron west. Traditional enemies such as the Cree to the north and the Illinois to the south continued to be the focus of annual Dakota war parties, but warfare with the Huron, Ottawa, and especially the Fox also became common. The Fox arrived in Wisconsin in the seventeenth century, driven from the Michigan peninsula by the Chippewa. Their arrival in what is now Wisconsin brought them into collision with the Eastern Sioux. Chippewa oral tradition holds that for a brief time the Fox actually occupied the upper Saint Croix valley and the region around Rice Lake, Wisconsin. The Dakota and the Chippewa began their relationship, which would later stain the waters of the Saint Croix with much blood, as allies against the Fox. In 1680, a joint Dakota-Chippewa war party, perhaps as many as eight hundred men, fell upon the Fox villages in east central Wisconsin. Only after suffering severe losses were the Fox able to repulse the attack. [16]

As the enemy of the Dakota's enemy, the Chippewa became neighbors with whom the Eastern Sioux shared hunting grounds, trade, and brides. The Chippewa originally entered the river and lake country of the Wisconsin border as Dakota guests, not as invaders. As allies the Chippewa were allowed to hunt and trap in the St. Croix and Chippewa River valleys. It was an alliance of two of the most numerous and expansionistic native peoples of the North American interior sealed with Fox blood and sustained by substantial and mutual benefits. The Dakota shared in the Chippewa's regular access to French trading goods. The Chippewa won access to lands rich in white-tailed deer, beaver, and wild rice. The Dakota secured metal tools and firearms to improve subsistence activities and their military efficiency. According to Chippewa oral tradition, the Dakota first encountered firearms when a Chippewa peace delegation arrived in a Sioux encampment on the St. Croix River. The incident ended badly when a proud Dakota warrior denied the power of a musket and dared the Chippewa to shoot at him. One fearful crack of the gun led to the death of the Dakota. This incident damaged the alliance. Nonetheless, relations were patched and early in the eighteenth century the Chippewa were allowed to establish a village in Dakota Territory, just south of the current national riverway, near Spooner, Wisconsin. [17]

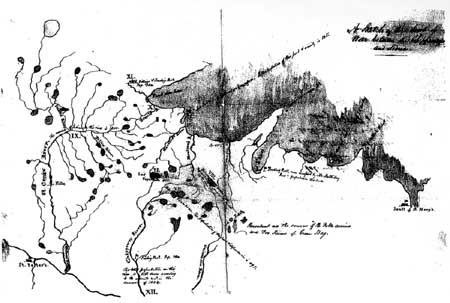

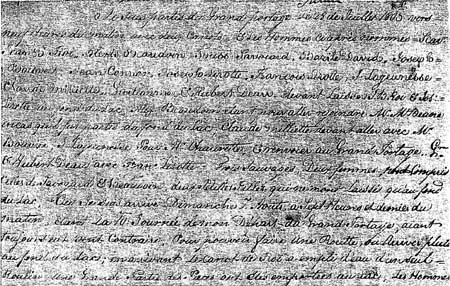

Figure 2. "A Sketch of the Seat of the War Between the

Chippewa and Sioux," by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Courtesy of the Clements

Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

French Fur Traders on the St. Croix

By the beginning of the eighteenth century regular access to firearms had become vital to the Dakota. French fur traders pushing up the Mississippi River had armed their traditional enemies in the Illinois country, while the coureurs de bois of the Great Lakes region had provided enemies to the east, such as the Fox, with muskets and powder. Those enemies and the remoteness of the Dakota lands frustrated the efforts of early French traders to establish themselves among the Eastern Sioux. The first European to enter the Dakota lands along the St. Croix was Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Luth. In 1679 the explorer claimed the region for France, offered gifts to the eager Dakota. At the mouth of the St. Croix he secured the release of Father Louis Hennepin, a Recollet missionary whom they had taken prisoner on the Mississippi. Duluth made the first recorded passage of the Bois Brule–Saint Croix portage that allowed passage from Lake Superior to the Mississippi valley, a route he likely learned about from the Chippewa at La Pointe.

The name of the St. Croix River dates from this early period of French activity in the Upper Mississippi region. Hennepin tried to fix on it the name Riviere du Tombeau, or River of the Grave, after the Dakota buried a snakebite victim on its bank. That name did not take, nor did one that appeared on several early maps, Riviere de la Madeleine. Many stories concerning the name St. Croix link it to the early missionaries. One story of its evolution credits the name to French priests, who saw the shape of a holy cross in the river's right angle junction with the Mississippi. Another version attributed the name to a rock formation on the bank of the river in the Dalles that appeared to have the shape of a cross. Other than Hennepin, who tried to put a morbid name on the river, the only other early missionary to see the river was the Jesuit Gabriel Marest. He was a missionary to the Dakota and witness to Nicholas Perrot's vainglorious ceremony of "taking possession" of the region in 1689. In that ceremony Perrot claimed "in his Majesty's name" a vast track of land stretching westward from Green Bay, including "the rivers St. Croix and St. Peter, and other places more remote." The use of the name St. Croix at so early a date suggests the river may indeed have been named, like the St. Peter's River, by missionaries. The more widely accepted story of the origin of the name credits it to a French fur trader named St. Croix or Croix who allegedly was wrecked or drowned at the mouth of the river. This story dates from Benard de la Harpe's 1700 account of Pierre Charles Le Suer's journey a year earlier up the Mississippi to the Minnesota River valley. "He left on the east of the Mississippi, a great river," La Harpe wrote, "called St. Croix, because of Frenchman of that name was wrecked at its mouth." While the exact origin will never be known for sure, the name St. Croix is one of the earliest European places names in the upper Midwest region. [18]

Other missionaries and traders followed and a series of trading posts were temporarily established in the late 1600s and early 1700s along the Upper Mississippi or lower Minnesota rivers. Each venture, however, failed due to distance and the opposition of the Fox, who attacked posts and hindered resupply efforts. In 1695, Tiyoskate, a Dakota emissary to the Governor General of New France, with carefully staged tears in his eyes, implored, "All the nations had a father who afforded them protection; all of them have iron." He concluded by describing himself as a "bastard in quest of a father." Although the Governor was stirred to grandiloquently promise Tiyoskate the "iron" tools and weapons, Dakota trade contacts remained intermittent. All of which served to make the alliance with the Chippewa more important to the Dakota. [19]

The Sioux made French efforts to extend trade to them more difficult by refusing to forgo their wide-ranging military campaigns. With the firearms they were able to obtain the Dakota ravaged the Illinois country. In 1700, French officials encountered Piankashaw Indians in Illinois who were attacked by recent Dakota raids. They had been so devastated by this event that they were unwilling to risk retaliation. This aggressive approach to their southern frontier even extended to French traders moving north from Illinois, whom the Dakota routinely robbed, as they were regarded as allies of the Illini, Miami, or Piankashaw. This vigorous approach to war, together with the large number of warriors the Sioux were traditionally able to marshal for war inclined the French to refer to the Dakota as the "Iroquois of the West." [20]

But the power of the Dakota began to ebb in the early eighteenth century. As early as the seventeenth century the Sioux were divided into two distinct groups. In 1680, Father Louis Hennepin described one subdivision of the Sioux as the "Tinthonha (which means prairie-men)." Pierre Charles Le Sueur, who attempted to establish a trading post (just below the mouth of the St. Croix) among the Sioux in 1694, distinguished between the "Sioux of the West," who resided along the Minnesota River and the "Sioux of the East," who dwelled along the Upper Mississippi. During the late 1600s the western Sioux began to expand from the Upper Minnesota River, over the plains to the Upper Missouri River country. This historic migration would in the course of the next century bring the bulk of the Sioux from the forest to the grasslands. The birchbark canoe was gradually forsaken in favor of the horse, which the Sioux began obtaining by trade around 1707. Buffalo hunting went from being one part of the annual seasonal cycle, dictated by the arrival of bison herds along the Upper Mississippi, to the sustaining food source available year-round to hunting villages made mobile by the horse. [21]

Like all movements of peoples this one resulted from both a perception of opportunity and the dictates of necessity. As warriors the Sioux were engaged in conflict on all of their frontiers. Opponents to the north, south, and east were all as well or better armed than the Sioux. To the west, however, were Indian peoples whose trade contacts with European fur traders were inferior to those of the Sioux. Nor was the population size of the Upper Missouri peoples as formidable as Wisconsin, which became densely populated with Indians fleeing the Iroquois. Although the Sioux appear to have been largely successful in defending their large rich homeland in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the soft frontier to the west drew aggressive Sioux warriors out on to the plains. Another factor was the opportunity to secure buffalo seemingly at will. The buffalo hunt was a defining cultural element among all the Sioux, their grand group experience. To build a lifestyle around it must have been alluring. Particularly because, hunting options in Minnesota may have declined at the critical time of the move on to the plains. In 1717 and 1718, French traders noted that animal populations south and west of Lake Superior declined due to an unknown disease. "All the elk were attacked by a sort of plague, and were found dead," according to one report. Indians who ate the flesh of the infected animals also died. There is evidence that by the 1730s even the eastern most Dakota, the Mdewakantons, were forced to substantially increase their reliance on buffalo hunting, perhaps due to a decline in the elk herds. If buffalo was becoming the dietary backbone of many Sioux, the movement on to the plains made economic sense. [22]

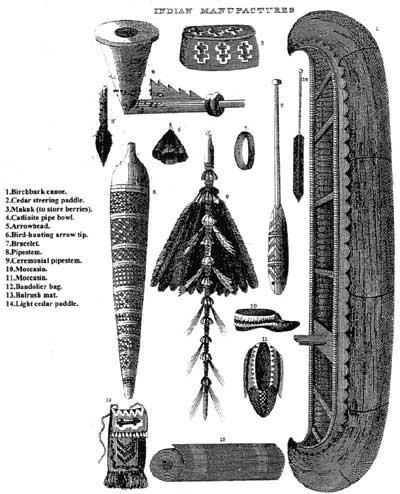

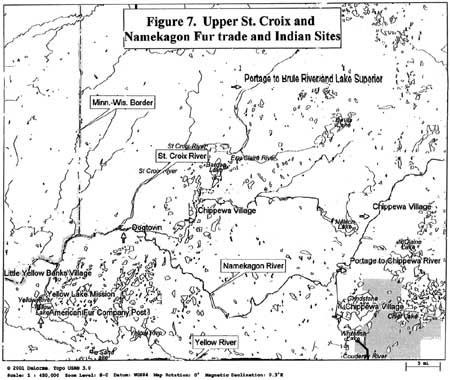

Figure 3. Items fashioned by Chippewa craftsmen from the

northwoods environment. Neither the Chippewa nor the Dakota were

dependent upon the fur trade for survival in the St. Croix valley. From

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's Travel Through the Norhtwestern Region of

the United States, 1821.

The Origins of the Dakota-Chippewa War

As the Sioux nation as a whole expanded westward, the Dakota, manning as it were the eastern gateway to their lands, were placed in an untenable position. The Sioux in the west were no longer available for, nor interested in fighting battles against traditional enemies on the eastern border. As the Sioux frontier expanded dramatically to the west, the ability of the nation to maintain its control over the large and rich hunting grounds along the Upper Mississippi was necessarily compromised. For all their military prowess and impressive numbers the Sioux could not dominate both the northern plains and the Upper Mississippi valley, as the western bands moved to accomplish the former, the eastern Dakota were thrown into a desperate attempt to maintain the land of their fathers. New diseases introduced by the Europeans, especially smallpox and malaria, together with the accelerated pace of intertribal warfare also contributed to the decline of the eastern Dakota. Between 1680 and 1805 the number of Dakota in the Mississippi valley may have declined by as much as one-third. These factors, together with the migration of their western kinsmen made the Dakota vulnerable to the equally expansionistic Chippewa. [23]

The Chippewa pursued their own manifest destiny in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the ancient traditions of the tribe the Chippewa once inhabited lands near the Atlantic Ocean. Upon migrating to the Great Lakes region they split into three groups, the modern Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Chippewa. The latter group occupied a vast arc of lands stretching from the shores of Lake Erie to rivers and lakes west of Lake Superior. This vast homeland was much larger than even the domain of the Dakota, but it was much less diverse in its landforms and, therefore, less abundant in resources, notably lacking the sustaining herds of elk and buffalo. Fish from the Great Lakes filled the protein gap for the Chippewa, but they did not produce the residuals of leather and robes. Together with their Potawatomi and Ottawa cousins the Chippewa had been among the earliest interior tribes to become engaged with the fur trade. As traders and trappers they were always on the lookout for new peoples with which to exchange or new lands to trap. Through the seventeenth century the Dakota both provided the Chippewa with furs and made their hinterland available to pioneer Chippewa bands. This economic alliance became frayed when the Dakota were gradually able to obtain European weapons and goods directly from the French. In turn, the Dakota came to resent the Chippewa's middleman commerce with the Cree and Assiniboin, hereditary enemies of the Sioux. [24]

Violence between the Chippewa and the Dakota began slowly in the 1720s and escalated to a full, prolonged war in 1736. Conflict between the tribes forced the Dakota to abandon traditional wintering villages at Leech Lake and Mille Lacs, sites that were soon colonized by the Chippewa. In the oral tradition of the latter this process was rendered heroic by tales of an epic battle of three days that left the former Dakota villages littered with the bodies of the slain Dakota. More plausible was a calculated withdrawal closer to the increasingly more important buffalo herds along the Mississippi and away from regions exposed to both Chippewa and Cree attack. Far from being completely routed from the region, the Dakota continued to occupy a village on the Rum River (which drains Mille Lacs) for another generation. The bulk of the eastern Dakota, however, concentrated along the mainstream of the Mississippi River and the lower St. Croix. During the seventeenth century the Dakota did not use the St. Croix as intensively as they did the large headwaters lakes in north-central Minnesota. As a result it was in the 1700s a much more reliable source of game. Not surprisingly, control of the hunting grounds and rice marshes of the St. Croix were hotly contested by both sides in the war. [25]

The Dakota-Chippewa war was a tragedy for both peoples and a source of frustration to the Europeans who, during the 1700s, began to influence events in the Upper Mississippi region. Conflict made the already precarious existence of a frontier fur trader downright dangerous. Men supplying weapons to one side were naturally regarded as enemies by the other and were often dealt with violently. In 1741, following Chippewa attacks on two Dakota camps; the latter retaliated against French traders in Wisconsin. Warfare also hurt trapping, as Indian hunters were reluctant to stray far from their family's winter camps. In the more than a century and a quarter that the Chippewa and the Dakota were locked in warfare, European traders repeatedly tried to arrange truces. This desire for parlays on the part of the Europeans should not obscure the fact that fur traders sometimes, often unknowingly, encouraged hostilities between the Dakota and Chippewa. Traders based on the Upper Mississippi and dwelling with the Dakota naturally supported Sioux claims to the St. Croix while those based on Lake Superior and in Chippewa territory naturally desired their hunters to dominate as large an area as possible. Most of all traders wanted fur trapping to be pursued aggressively. During the early 1730s, when the conflict between the two tribes began to simmer, French fur traders exasperated the situation by encouraging Chippewa and Winnebagos to expand their trapping grounds along the Upper Mississippi. The fur traders did not think the Dakota were tapping anywhere near the full potential of their rich trapping grounds and impatiently encouraged interlopers to fill the perceived void. The entire history of the fur trade in the St. Croix valley took place under the cloud of a bloody, often internecine, war. [26]

The experience of Paul and Joseph Marin, French fur traders in the region from 1750 to 1754, reveals the relationship between war, peace, and trade. By bringing the Governor General of New France into partnership, Paul Marin, a veteran fur trader, was granted a lease to the fur trade of the Upper Mississippi. Marin's political connection initially assured that the vital access points to the region, Green Bay, which controlled the Fox-Wisconsin water route to the Mississippi, and La Pointe, which was critical to the Bois Brule-St. Croix route, were controlled by his friends. In fact his son Joseph was granted command of the La Pointe garrison. The elder Marin astutely cultivated Dakota leaders. Canoe loads of gifts were lavished on them and in turn they acted as trading liaisons, collecting furs from all of the hunters who had received goods in advance from Marin. The French extended their trade presence to most of the villages of the eastern Dakota and were rewarded with annual returns of 150,000 francs. Meanwhile, young Joseph Marin, based in Chippewa territory, worked to ease tensions between his trading partners and the Dakota. Eventually the father and son managed to work out a division of the disputed territory. On the St. Croix this led to the Dakota recognizing Chippewa rights to the valley from its headwaters to the mouth of the Snake River. When the Chippewa expressed a desire to trap along the Crow Wing River, a substantial tributary of the Mississippi roughly midway between Leech Lake and modern St. Paul, Joseph Marin negotiated a lease between the rival Indian nations. [27]

The tenure of the Marins demonstrates that properly managed the fur trade could have been a means to control the level of violence between the Chippewa and the Dakota. Yet the corrupt French colonial administration in Quebec had different priorities and would not long manage its western affairs in a consistent manner. Paul Marin's appointment to the Upper Mississippi had been made with the assurance he share the profits with the Marquis de la Jonquiere. That venal administrator assured that New France's western posts were under the direction of administrators friendly to Marin and sympathetic to the Dakota. A new governor general, however, would find profit in other arrangements. Therefore, in 1752 when the Marquis de la Duquesne succeeded to the Governor General's palace Paul and Joseph Marin lost their official protection. The command of the critical French post of La Pointe on Lake Superior passed to Louis-Joseph La Verendryes. This very capable frontier leader was in no mood to cooperate with the Marins. While they had been profiting mightily from the Dakota trade, La Verendrye and his equally talented father and brother had been denied any position in the western trade by Governor General Jonquiere. Far from being sympathetic to the Dakota, La Verendrye had every reason to resent them as a Sioux war party attacked and killed his brother and twenty-three other men at Lake-of-the-Woods in 1736. The La Verendryes were dedicated to expanding French influence west of the Great Lakes, which made them dependent upon a close relationship with the Chippewa and the Cree. The result of La Verendrye's appointment was a quick erosion of the truce and trust the Marins had succeeded in building. [28]

The first sign of trouble was when La Verendrye notified Joseph Marin that the former's La Pointe post trading area included the entire St. Croix River valley. La Verendrye intended to have complete control of the upper Mississippi region. In 1753, he dispatched several of his traders to establish a wintering post on the St. Croix near the Sunrise River. La Verendrye then intercepted and turned back agents Marin had sent up the Mississippi to Leach Lake to negotiate a peace between the Dakota and the Cree. This latter action spread panic among the Dakota, who saw it as a repudiation of French friendship and the prelude of new attacks by the Cree and the Chippewa. Bracing for war the Dakota abandoned their hunts and suffered through the winter of 1753, bereft of game for their lodges or furs for Marin. Dakota women and children "lived on nothing but roots all winter long," they complained to Joseph Marin. "That is why today we are worthy of pity." The Dakota further complained that the Chippewa were violating their earlier agreement to hunt along the Crow Wing River for a single year, even though "they know those territories belong to us." As a result of these outrages the Dakota chiefs told Marin "we cannot keep from you the fact that our young men are all beginning to mutter at seeing the Sauteux [Chippewa] so unreasonably trying to steal territories belonging to us." The young Dakota were wise to mutter because La Verendrye clearly had the upper hand over Marin. After 1754 Joseph Marin left the Upper Mississippi country and French commanders at La Pointe tilted their policy in favor of Chippewa expansion. [29]

For close to a decade the French and Indian War (1754-1760) and Pontiac's Rebellion (1763) interrupted the flow of trade goods into the St. Croix valley, and temporarily reduced the importance of the fur trade in lives of the area's embattled inhabitants. The Dakota-Chippewa conflict, however, continued. A large battle was fought near what may have been the headwaters of the St. Croix. The Chippewa suffered heavy losses in the engagement but the Dakota were forced to yield the field. The Dakota seem to have more than held their own throughout the 1750s and 1760s. When the first British observers entered the Upper Mississippi region in 1766 they found the Dakota disdainful of their enemies, whom they referred to as "slaves or dogs." Their lodges were well supplied with meat and feasting continued through the winter. On the other hand the Chippewa, still lacking access to buffalo and Elk, seem to have suffered from the temporary cessation of the fur trade. Alexander Henry, the first British merchant to reach them after the fall of New France, found famine stalking the Lake Superior Chippewa. "These people were almost naked, their trade having been interrupted, " he noted in his memoir. [30]

The late 1760s and early 1770s saw an intensification of the fighting between the Dakota and the Chippewa. Traders operating from La Pointe on Lake Superior likely encouraged the Chippewa to increase their fur returns by expanding their hunting in Dakota Territory. Sometime about 1770 one of the greatest battles of the long war was fought at the Dalles of the St. Croix. The best account of what occurred comes from Chippewa oral tradition recorded in 1885 by William Warren a Metis historian of Chippewa ancestry. According to his sources the campaign began at the instigation of the Fox Indians who ascended the Mississippi desirous of settling the score with the Chippewa, their hereditary enemies. The Dakota, former enemies of the Fox, were enlisted to make a joint attack. The combined war parties made their way by canoe up the St. Croix. On the portage trail around St. Croix Falls, the Dakota and Fox encountered a large Chippewa war party intent on raiding the Dakota villages along the lower river. The Chippewa had been smarting from numerous successful Dakota raids on isolated hunting camps along the St. Croix and Namekagon. Waubojeeg, a renown Lake Superior leader had gathered warriors from across northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. He led his large war party up a branch of the Bad River portaging eight miles west to the sources of the Namekagon River. Waubojeeg directed the advance down stream cautiously, so when they reached St. Croix Falls his scouts informed him of the large enemy force ahead. Just before the fighting commenced the veteran Chippewa fighters pushed those going into battle for the first time into the river. There the novices washed off the black paint that had stigmatized them and they were allowed to join the warriors as equals. [31]

The two forces met in combat on the portage trail. Fighting between the Fox and the Chippewa marked the first phase of the battle. Allegedly the Fox had boasted that they would make short work of their enemies and requested the Dakota to remain aloof from the fighting. Confined by the ravines and rock outcroppings of the portage the fighting was heated and at close quarters. About midday the Chippewa gained the advantage and forced the Fox to flee. At the point of driving the latter into the raging river, the Chippewa were staggered by the sudden entrance of the Dakota into the battle. After several more hours of combat the Chippewa, most of their ammunition exhausted, broke and ran from the Dakota. Victory was at hand for the Sioux when a war party of Sandy Lake Chippewa suddenly made their appearance on the field. They had missed their rendezvous with Waubojeeg's main force and had hurried downriver, arriving at a crucial point in the contest. This reinforcement turned the tide of battle for the final time. The Dakota attack was broken and their warriors were sent into a headlong retreat. "Many were driven over the rocks into the boiling floods below, there to find a watery grave," Warren recounted. "Others, in attempting to jump into their narrow wooden canoes, were capsized into the rapids." The Chippewa and Dakota both suffered heavy losses, but it was the proud Fox who left the most dead amid the rocks and cervices of the battlefield. The victory secured for the Chippewa the control of the Upper St. Croix valley. An informal boundary was fixed between the Dakota and the Chippewa around the mouth of the Snake River. [32]

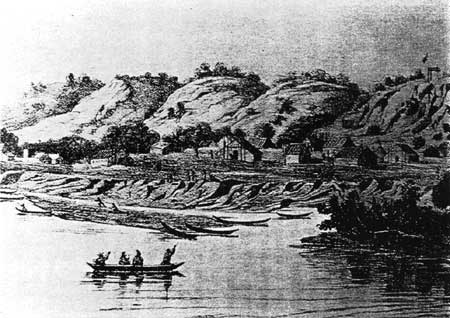

Figure 4. Little Crow's Village on the Mississippi near

the mouth of the St. Croix. From Henry Lewis, Das illustrite

Mississippithal (1848).

English Fur Traders on the St. Croix

The first English fur trader to penetrate the Lake Superior country was Alexander Henry. Henry's access to the remote frontier was made possible by his astute alliance with Jean Baptiste Cadotte. The latter was a key figure in bridging the end of the French regime and the era of British domination. Cadotte's family had long been involved in the western fur trade. He grew up in the Lake Superior country and married the daughter of a notable Chippewa chief. Cadotte had served as the last French governor of the fort at Sault Ste. Marie and earned the trust of the English conquerors by being one of the first French traders to embrace the new regime. When Jean Baptiste Cadotte retired from the trade, his son of the same name took his place. The latter played a lead role in reopening the fur trade of the Upper Mississippi valley. A second son, Michel Cadotte was active on the St. Croix and Chippewa rivers. In 1784 he operated a post on the Namekagon River, near the head of the portage to Lac Court Oreilles. Latter he established trading posts at Yellow Lake, Snake River, and Pokegama Lake. The key to the success of the Cadottes was their family relationship with notable Chippewa leaders. They consciously identified themselves with the expansion of the Chippewa into the St. Croix and Upper Mississippi valleys, advancing hand in hand with bands of hunters to exploit the bounty of Dakota hunting grounds. [33]

Archeologists have long puzzled over the identification of Michel Cadotte's 1784 trading post on the Namekagon River. In the early 1960s local historian Tony Wise conducted an archeological study of a site he thought was the trading post. Among the items found that supported that conclusion were the sideplate of a trade gun and a number of gunflints. Further study by National Park Service archeologists, however, revealed that the overwhelming majority of artifacts at the site date from the mid to late nineteenth century. It is possible that trappers or loggers reoccupied the Cadotte post site in the 1870s. The structural depressions at the site are mostly the remains of that latter occupancy and not remains that date to the British era of the fur trade frontier. [34]

While Alexander Henry did not venture far south of Lake Superior, Jonathon Carver, another young Englishman on the make, explored the Upper Mississippi frontier. Ostensibly Carver was a mapmaker sent with explorer James Tute, a Captain in the famed Roger's Rangers, to discover an inland route to the fabled Northwest Passage. Carver journeyed from Mackinac across Wisconsin and wintered among the Dakota villages of the Minnesota River valley. He was fascinated with the Dakota whom he described as "a very merry sociable people, full of mirth and good humor." He explored the Upper St. Croix valley by portaging from Lac Courte Oreilles to the Namekagon River near present day Hayward, Wisconsin. Carver descended the Namekagon, which he named "Tutes branch" to its junction with the main stream. James Goddard, the official secretary of the expedition, described the Namekagon as "a very pleasant country, and plenty of deer in it." Above the junction of the Namekagon and St. Croix Carver tried his hand at sturgeon fishing. "The manner of taking them is by watching them as they lie under the banks in a clear stream, and darting at them with a fish-spear; for they will not take a bait." Carver dubbed the St. Croix from the Namekagon to its source the "Coppermine Branch," due to the "abundance of copper" found along its banks. The region of the headwaters he laconically noted was known to the Chippewa as "the Moschettoe [mosquito] country, and I thought it most justly named; for, it being then their season, I never saw or felt so many of those insects in my life." More significantly for the future of the fur trade he noted that along the Upper St. Croix "rice grows in great plenty." Carver then followed the portage trail from Upper Lake St. Croix to the Bois Brule River and Lake Superior. [35]

Although his time in the St. Croix valley was brief Carver's legacy lingered longer in the form of a narrative Travels Through North America in the Years 1766, 1767 and 1768. This widely read and frequently translated account of the Upper Mississippi region provided generations of readers with their first exposure to the region. Like so many would be explorers before and after, Carver mixed genuine observations with heavy doses of romantic fancy and self-promotion. Captain James Tute who actually directed the expedition goes all but unmentioned in the published narrative, creating the impression that Carver was the man in charge. His enthusiasm for the region was effusive. The Upper Mississippi region was "abounding with all the necessaries of life, that grow spontaneously; and with a little cultivation it might be made to produce even the luxuries of life." He did not simply note stands of maple trees but went on to predict that the "delightful groves" were present in "such amazing quantities" that they "would produce sugar sufficient for any number of inhabitants." If the principle purpose of Captain James Tute had been to evaluate the fur trade prospects of the region, the purpose of Carver's book, which he did not publish until 1778, was to promote Carver by giving the impression that he had single handedly opened up a utopia for future settlers. He went so far as to produce a map in which he divided the Upper Midwest into a series of "plantations or subordinate colonies" so that "future adventurers may readily, by referring to the map, chose a commodious and advantageous situation." With this map Carver also established symbolic mastery over the region, inviting his numerous readers in the decades that followed to project their dreams on to this open and free land. [36]

Carver included the bulk of the St. Croix valley in his "plantation No. 1," which included a great triangle of territory that reached as far northwest as Rainey Lake and to Sault Ste, Marie on the east. "The country within these lines," he observed, "from its situation is colder that any of the others; yet I am convinced that the air is much more temperate than those in provinces that lie in the same degree of latitude to the east of it." With this claim Carver anticipated the logic of virtually every land promoter to follow. Don't let the far northern position of the Saint Croix valley daunt settler's dreams of an agricultural future. Not only was the climate more temperate than what people knew in the east "the soil is excellent, and there is a great deal of land that is free from woods in the parts adjoining the Mississippi." Of course, if the settler preferred trees, Carver allowed that the "north-eastern borders" of the region were "well wooded." In addition to abundant rice and copper, settlers were also blessed with the presence of the "River Saint Croix, which runs through a great part of the southern side of it, enters the Mississippi just below the falls, and flows with so gentle a current, that it affords convenient navigation for boats." Carver was so impressed with the prospects for the region that he passed to his heirs a fraudulent document, which claimed the cession of a large tract of land. Allegedly the Dakota granted him twelve million acres of land, including a sizable portion of the St. Croix valley. Neither the British crown, the Eastern Sioux, nor latter the United States Congress saw fit to recognize the Carver Grant as valid. In 1817 two of the explorer's grandsons actually journeyed back to the Upper Mississippi wilderness to have Chippewa and Dakota elders substantiate the alleged grant. Not surprisingly they went home with no more land than when they set out. [37]

While the Tute-Carver expedition was supposed to be directed to discover the Northwest Passage a large part of its real orientation was to probe the commercial opportunities of the Upper Mississippi frontier. In the 1760s only a geographic idiot would have spent weeks ascending the Chippewa River and the Upper St. Croix in search of the fabled water route to China. The fur trade was on the mind of many of the British who went west after the French and Indian War. One of those who left a record of their efforts was a cantankerous Connecticut Yankee named Peter Pond. He did not leave a description of the fur trade on the St. Croix itself, although he was active with the Dakota in the Upper Mississippi valley. Pond did describe the process by which merchants of English origin began to dominate the trade of the region because of their superior ability to obtain credit and merchandise as well as their ability to act in concert with British military forces and thereby pose as power brokers between tribes. Both Carver and Peter Pond attempted to negotiate a peace treaty between the Dakota and the Chippewa. Each was more successful in arranging a parlay, than a lasting peace. In 1775 Pond escorted a group of Dakota and Chippewa chiefs to Mackinac where an agreement was struck by which the Dakota agreed "Not Cross the Missacipey to the East Side, to Hunt on thare Nighbers Ground." That the Dakota would agree to recognize the Chippewa as masters of the area east of the Mississippi would have been a major concession and was likely the result of Pond's failure to obtain a delegation of the eastern most Dakota tribe, the Mdewakanton Sioux. A British military inspection of the region in 1778 led by Charles Gautier de Verville reported a large Mdewakanton village on the Upper St. Croix River. The village included a number of lodges of Winnebagoes, a people who shared the Dakota's antipathy of the Chippewa. Clearly the Mdewakanton had not abandoned the east bank of the Mississippi to the Chippewa. [38]

The arrival of the British regime along the Saint Croix signaled a change in the way the fur trade would be administered. The French system of leasing the right to control the trade in a large geographic area, while never able to keep all illegal Coureurs de bois out of business, did tend to greatly restrict the number of traders operating in any one area. Under the British and even more so under American administrations there was much less regulation of the fur trade and an ever-growing number of participants made their way west. More participants meant more competition and less concern on the part of many traders for the long term good of both the fur trade itself and the Indian trappers in particular. One of the early innovations of the British regime was the establishment of companies that pooled the resources and special skills of a group of fur traders. The Northwest Company, founded in 1779 was an attempt by Peter Pond and other fur traders to establish greater control over competition in their business. The Northwest Company, based in Montreal, exerted a considerable influence over the fur trade of the St. Croix River during the years between its creation and 1816. United under its control were many of the traders who had expanded the trade since the fall of New France, including Alexander Henry and Jean Baptiste Cadotte and his brother Michel Cadotte.

Independent fur traders operating out of Green Bay also wintered on the St. Croix during the last years of the eighteenth century. Augustin Grignon, a member of the fur trading clan that dominated the "La Baye" fur trade, operated a post in the valley in 1792. A year latter his operations there were directed by Jacques Porlier, who was beginning a long career in the fur trade. A Mackinac trader, Laurent Barth, also operated a trading post on the river that winter, building close enough to Porlier to allow frequent visits between the two. A lack of specific locational information in the historical record has frustrated the identification of these posts as historic sites. The Green Bay traders entered the valley accompanied by Menominee hunters. The Menominee had long hunted along the headwaters of the Chippewa River, taking advantage of beaver country less heavily trapped than their own homelands along Lake Michigan, but it was rare for them to venture into the St. Croix valley. These hunting expeditions included family groups and were usually undertaken only with the permission of the Dakota. [39]

Figure 5. Jonathan Carver's Map of the Upper Midwest

Region, published in 1778.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

A Social History of the Fur Trade in the St. Croix Valley

One of the enduring historical myths of the Upper Midwest is the heroic image of the fur trade explorer and his hardy voyageur companions. The myth rests on the very real role these men played establishing the first white businesses and settlements in the region and the romantic impulse of those who latter read the trader's memoirs and journals to try and imagine just what the Midwest looked like when all was wilderness. Fur traders did act as wilderness explorers but many aspects of their business were anything but heroic. It is vital to balance the picture of the fur trader as an explorer and pioneer with the less flattering portrait of the fur trader as a pusher of dangerous and addictive substances, a fomenter of intertribal and intratribal conflict, and as a participant in environmental degradation. Nor is it historically valid to dismiss their Indian trading partners as innocent victims. The fur trade brought the Indians products vital to life in the forests of the Upper Midwest: copper kettles, steel knives, firearms, and wool blankets. The fur trade was neither a European creation nor an Indian innovation but a social and economic process forged out of desire for a better life and all too human weaknesses. Fur traders, the Chippewa, and the Dakota of the St. Croix were joined together in a commerce that was at once alluring, enriching, dispiriting, and destructive.

Documenting the exact nature of the fur trade in the Wisconsin and Minnesota is complicated by the spotty nature of the surviving historical sources. While little can be said about the French era along the St. Croix, for example, there are other periods when the historical record opens up a window on the fur trade. One such time is the period between 1802 and 1805. George Nelson, a veteran Nor'Wester, produced a memoir of his first year as a fur trader, which he spent in the St. Croix Valley from 1802 to 1803. Michel Curot left a journal of his year as a fur trader in the region during the winter of 1803-1804. Finally, the much-studied journal of John Sayer documents the 1804-1805 trading season. All three men established posts in different parts of the St. Croix Valley: Nelson at Yellow Lake, Curot on the Yellow River, and Sayer on the Snake River near modern day Pine City, Minnesota. The period from 1803 to 1805 was a tense time for the fur traders because of a split in the ranks of the Nor'Westers. One of the most prominent members of the Northwest Company, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, along with several other partners, split with the established firm and formed the rival New Northwest Company. Known on the frontier as the X Y Company, the upstarts went head to head in competition with the Northwest Company, greatly expanding the demand for the fur and food produced by Indian hunters. [40]

Easily the most striking feature that emerges from a close reading of the 1802-1805 period is the importance of alcohol in the fur trade. The Northwest and XY companies hauled vast amounts of liquor over the portage between the Brule River and Upper Lake St. Croix. In 1803, Michel Curot reported to his superiors that the rival Northwest Company had brought in fifty-six kegs of high wine. This highly potent distilled beverage was akin to today's grain alcohol and like the latter had to be diluted before being consumed. Yet, even when broken down several times it remained very intoxicating. Archeologist Douglas Birk estimated that fifty kegs of high wine could be diluted into over one thousand gallons of liquor for trade. Added to this massive amount of alcohol was the much smaller volume of rum and high wine imported by Curot and the XY Company. Operating on a much smaller scale Curot had at least seven kegs of high wine at the start of the trading season and received an additional one in the spring. It is there for not unlikely that between them the fur traders had close to thirteen hundred gallons of liquor for the trading year. Fur Trader George Nelson estimated the Chippewa population of the area to be "not above fifty families" with "about 60, or 65 warriors." Even if one assumes a generous estimate of a two-to-one adult male-female relationship and a two-to-one children-adult ratio, the Chippewa in the region did not number more than four hundred people. This figure is consistent with the size of the St. Croix band in 1851 when American authorities proposed to move them west of the Mississippi River. In other words the fur traders in 1803 were stocked with enough alcohol to provide every adult Indian with more than seven gallons of high wine. [41]

While the years 1802-1805 may have been the high-water mark of the use of alcohol in the fur trade there is little doubt that spirits occupied a critical role in the trader's inventory both before and certainly afterward. Some Chippewa used alcohol in the same manner as most people today. The traders document tastings being offered to trappers coming to trade as a social prelude prior to conducting business or high wine being requested by Indians upon the death of a child as a consolation. But the ugly face of what may very well have been addiction also appears in the trader's journals. When sixteen-year-old fur trader George Nelson landed at the junction of the St. Croix and Yellow Rivers in 1802 he was greeted by a mob of young Indian men:

The Indians, the moment they saw us gave the whoop. They were all drunk, the N.W. Co. had a little before given liquor. They came rushing upon us like devils, dragged our Canoe to land, threw the lading ashore, ripped up the bale cloths, cut the cords & Sprinkled the goods about at a fine rate. Such noise, yelling & chattering! "Rum, Rum, what are you come to do here without rum?"

Only a year before on that very spot the Yellow Lake band and members of the Snake River band had suffered five dead, and six wounded when a drunken party led to a vicious knife fight. Nonetheless, the Chippewa refused to let the traders proceed until they assented to "make our presents of liquor also." The result was, according to Nelson, "singing, dancing & yelling, & fighting too." On January 4, 1804 John Sayer noted rather causally in his journal, "Indians still Drunk & Quarrelsome amongest themselves. 2 got Stabbd but not dangerous." Just over a week later he noted "this forenoon 2 Young Lads arrived from the Drunkards Lodge & report that the Indians were near Killing each other, at the same time requested a Small Keg of Rum which I refused them." [42]

As Nelson and Sayer's experience indicates the alcohol trade brutalized the Indians who then turned that behavior on the traders. A Chippewa he knew by the name of Le Grand Male frequently intimidated Michel Curot. On November 1, 1803 Le Grand Male arrived at Curot's door drunk from drink he had already procured at the nearby Northwest post and demanding more. Curot refused but Le Grand Male would not take "no" for an answer. "All The night it was the same Demand and the same reply," Curot reported. "I had much trouble with this savage. I received several Blows of his fist, one especially that made my upper Lip swell up." Two weeks earlier a group of Chippewa intent on a binge entered the Northwest Company post on the Snake River. They threatened to kill Joseph Reaume, the trader, tapped a barrel of pure rum, and "pillaged" the post for "ten days and ten nights." In January Curot again had problems when one of his assistants, Bazile David, refused to give rum to three Chippewa hunters who were spending the night at the post. Curot had already given them a small keg of undiluted high wine and the hunters were drunk. "A moment afterwards Le Jeune Razeur Like an enraged creature Struck David, saying to him, 'Dog, thou sayest that hast no Rum.'" The hunters then angrily left the post. They returned the next morning with a nine-gallon keg obtained from the Northwest Company and they demanded what rum remained at Curot's post. The trader anxious to match his competition and be rid of his troublesome guests acceded to the request. The abuse drunken hunters inflicted upon their own families went largely unrecorded. Although George Nelson noted one incident near the Brule Portage that provided an insight into what may have been all too common behavior. The traders had given rum to an Indian family with whom they had passed the night. The Indians drank through the night "very quietly & comfortably." Trouble came in the morning "when words ensued" and the son, a boy of sixteen or so years "fell upon this mother & beat her, striking with his fists & Kiicking her in the face & body!!!" Nelson's experienced companions dissuaded him from intervening, saying: "for if you do they will all three get upon you; besides it is among themselves–we dare not interfere." Shaken the young fur trader thought "Surely the curse of God will fall on these people." Little did he appreciate that he was that curse. [43]

How the St. Croix Chippewa viewed the traders and the impact of the fur trade on their lives and families can only be glimpsed at through the journals of the fur traders. Traders who came to establish posts along the St. Croix River did so at the sufferance of the Indians. While the posts were a convenience to the Chippewa, they seem to have adapted a proprietary attitude toward the goods the traders brought each fall. The Chippewa men who tore apart George Nelson's canoe's to find rum in 1802 were not humble supplicants awaiting a gift from the fur trader, rather they were men taking what they felt was their due. A year later when Michel Curot and his men came to blows with a group of hunters determined to have a keg of rum one of the Indians said "that it [the rum] all belonged to them, that in the Spring they would have some plus [beaver pelt]." George Nelson recorded in his reminiscences that Indians "would often. . .burst open the Shop door & take out what rum they pleased & compelled the people to mingle it to their taste." What traders regarded as begging or badgering by the Indians for something to drink was regarded by the Chippewa as merely giving them access to those things that were meant for them to begin with. [44]

Not all Chippewa embraced the fur trade with the same vigor nor did all become enamoured of high wines. George Nelson reported that one Chippewa leader admonished the traders "If you will persist to trade here, trade fairly as men & not wait till you think us too far drunk to perceive how you steal from us & insult our females." Others blamed the fur traders for the negative impact of alcohol on their lives. "You are the cause of this blood being shed by bringing poisoned rum to us," retorted one Indian after a drunken brawl. [45]

The drinking of the Chippewa must be viewed from the perspective of the high level of alcohol use in general on the frontier. The fur traders, although they seldom admitted it in their journals, which might be read by their superiors, often indulged in heavy drinking. Michel Curot noted in his journal that his rival John Sayer had an escalating drinking problem. "Since I have come into the fort I have noticed that Mr. Sayer is Very fond of Drink," wrote Curot, "there has been Scarcely a night, that he has not gone to bed Drunk." More scandalous to Curot than Sayer's habit of hiding pots of alcohol for himself about the post was the latter's willingness to drink the high wine prepared for Indian use. "I should Never have Believed that he would be fond enough thereof To Drink the Savage's Rum." Nor was Sayer selfish about sharing his drink with others. While his men labored to build the Northwest Company's Snake River post in 1804 Sayer noted in his journal that he "gave each a Dram morning & Evening & promised to do the same till our Buildings are Compleated provided the[y] exert themselves." Providing men engaged in heavy labor with alcoholic stimulants was standard practice in early nineteenth century business and in the armed forces. Nonetheless, Sayer was later dismissed from the Northwest Company, a decision that in part reflected his heavy use of alcohol. [46]

The presence of the fur traders in Chippewa territory, the heavy use of alcohol in their commerce, exasperated tensions that were already building among the St. Croix River bands. Compared with their Dakota rivals the Chippewa were highly individualistic. They lacked many of the rituals and shared experiences, such as the annual buffalo hunt, that made the Dakota a much more communal society. One of the reasons the Chippewa adapted much more readily to the new fur trade economy than the Dakota was their more fluid, independent social structure. Bands, even families, that simply acted for themselves with no restraints were able to adjust to the need to change geographic location or lifestyle much more rapidly than larger groups constrained by the need to form a consensus among many extended families. This flexibility and individualism were traits that had served the Chippewa well in the century and a half since the fur trade had begun. In fact these were traits that the Chippewa shared, although nowhere near to the same extent, with the growing number of Anglo-American settlers on the frontier. Nonetheless, as fur traders established more and more posts among the Chippewa and became a larger year round presence in their lives the bands became open to the interference and manipulation of the traders. [47]

One of the most divisive practices of the fur traders was the creation of chiefs. Traders attempted to elevate individual hunters status by giving them dress coats, flags, and other presents. They flattered themselves that if they treated this hunter as special he would be so regarded by other Indians in the community. Francious V. Malhiot, a Northwest Company trader in the Lac du Flambeau area made the following speech when he created a new chief:

Kinsman–The coat I have put on thee is sent by the Great Trader; by such coats he distinguishes the most highly considered persons of a tribe. The Flag is a true symbol of a Chief and thou must deem thyself honored by it. . .love the French as thou dost, watch over their preservation and enable them to make up packs of furs...As first chief of the place, thou must make every effort so that all the Savages may come and trade here in the Spring. . .

As Malhiot indicated the goal was to have this chief influence others to honor their debts at the trading post and not go to the competition. But far from picking the most admirable hunters (both from a Chippewa and a trader's perspective) men of the worst character were often selected by intimidated traders who hoped to end abusive behavior. In his memoir George Nelson described a group of frustrated traders who decided, "that by making a chief of the greatest scoundrel among them would perhaps have a good tendency." That was Malhiot's strategy in 1804 but it did not work. Similarly Le Grand Razeur, the Chippewa who attacked one of Michel Curot's men had earlier been made a chief. Worst of all chief making caused fissures among the Chippewa. Curot reported a stabbing among the Yellow Lake band during the winter of 1804. The "chief" refused to do anything to resolve the problem, "fearful on his own account." This caused Curot to reflect, "I believe that Band although Partly nephews and Brother in law [are] Jealous of whomever is made chief giving Preferment to any of them, Since each of them separately believes himself as Great a Man as an Other." [48]

The Chippewa often resented the practice of making phony chiefs. When John Sayer offered the coat and flag to the hunter Pichiquequi the latter responded angrily, even after Sayer tried to sweeten the offer with free rum. Pichiquequi "replied that he was not a chief and that Since he was thirsty he would go hunting either for a [fur] or a deer that he could trade for Rum, that he did not command any savages, that they were all Equal and [he and his people] would go where they liked to trade and that he himself would do the same."

A Chippewa hunter described in Nelson's memoir manifested this same spirit of independence. Following the formal presentation of the chief's uniform and flag the hunter turned to the fur traders with a look of "utmost contempt":

No doubt, you Frenchmen, you think yourselves wonderfully cunning: --no doubt you were very certain. . .. that my eyes would be blinded by the Dazzling stuff you have been Displaying here with so much ceremony before us? Undeceive yourselves. I am born free & independent. I despise those tokens of Slavery. I am not a Slave to wear oth[ers] clothing (livery). My old clothes satisfy me; & when they are worn out I know how to procure others.

Nelson was not present at the council when the traders attempted to elevate hunter to chief so the exact words he recorded must be regarded as narrative license. Nonetheless, the hunter's eloquent statement of autonomy and personal independence reflected sentiments that Nelson must have seen manifested many times in his long career of trading with the Chippewa. [49]