|

Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway

Time and the River: A History of the Saint Croix A Historic Resource Study of the Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway |

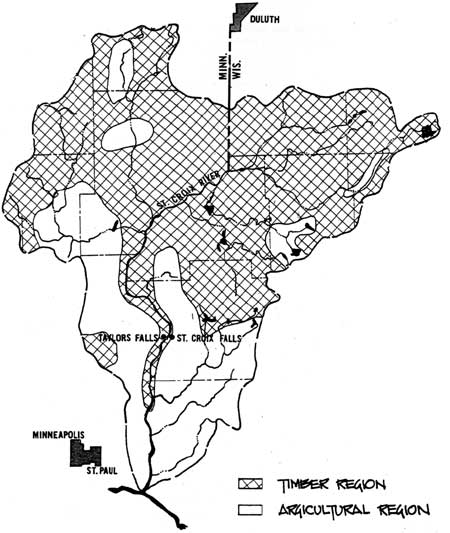

|

CHAPTER 2:

River of Pine

For nearly 150 years European and American merchants had passed through the St. Croix Valley, attentive to the number and location of Indians within the valley, mindful of the presence of wild game, sometimes observing its agricultural prospects, but largely unconcerned about the timber resources of the region. The bright and articulate George Nelson, who first entered the river valley in the fall of 1802, was an exception. The "beautifully wooded" islands and hills of the valley struck him, and with a merchant's eye he predicted they could be as commercially important as the timberlands of the St. Lawrence valley. The St.Croix's "splendid groves of pine" he wrote "could as easily be floated down the Mississipy as from Chambly to Sorel." More typical, however, was the U.S. Army Lieutenant James Allen's terse dismissal of the upper Saint Croix landscape as "poor, and pine; none of it fit for cultivation." [1]

Interest in the region's forest resources dramatically increased during the 1830s. The French scientist Joseph N. Nicollet, who journeyed up the valley in August of 1837, reflected this new interest in the valley's forests. In passing the mouth of the Sunrise River he noted "The banks of the St. Croix are still covered with black alder, sumac five or six feet tall, white and red oak, soft maple and some walnut or oil nut or shagnut trees. White pines are mixed with deciduous trees, and there are wild plum trees on the ridges." Above the mouth of the Snake River he noted that the patches of tall dark pine became more abundant. "They crown the peaks of hills and mix with other species which border the St. Croix." Nicollet's heightened appreciation of the region's forest cover may simply reflect his educated eye, but it is likely that he understood that during the 1830s trees replaced furs as the most coveted commodity within the valley. [2]

Nicollet's journey up the St. Croix came at a critical time in the region's history, as federal agents were negotiating to clear Indian title to the valley. The impetus for this change was a rising chorus of voices demanding access to the pine forests of the St. Croix. Forests hardly worth noting a generation before had been rendered into promising assets by the growth of towns and farms in the valley of the Mississippi. The St. Croix, Chippewa, Red Cedar, and Rum Rivers, all tributaries of the Mississippi that boasted vast forests of pine became the wooded hinterland that helped to build downriver towns such as Winona, Rock Island, Davenport, and St. Louis. In the post-Civil War era the demand became even more insistent and the market more lucrative as the treeless plains were surveyed into 160-acre homesteads. The exchange of a sod house for a frame home built of Wisconsin or Minnesota pine was a badge of success for the homesteader and the basis of many a lumber baron's fortune. [3]

The fur trade had divided the St. Croix valley between a upper river dominated by the Chippewa and economically tied to Lake Superior, and a lower river, home to the Dakota and linked to St. Louis based traders. In terms of transportation geography the logging frontier would restore the unity of the valley. The entire river system would be harnessed to bring the winter's harvest of logs to the collecting booms along the lower river. Like a funnel the St. Croix River was used to concentrate the wealth of the entire valley at its mouth. The forests of the upper river played a large role in building towns and the industry along Lake St. Croix, as well as the nearby cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis. The logging frontier first made manifest the dichotomy of a thinly inhabited upper river resource frontier and the prosperous urbanized lower river. In the course of doing so it wrought a massive transformation of the valley's landscape and severely, in some cases irrevocably, altered its ecosystem. Through its involvement in the lumber industry the St. Croix played its most important role in American history, but at a cost still being exacted today.

Lumbermen attempted to transform the free flowing wild river into a disciplined industrial waterway. Never before and never again would the river be used so intensely. Mill operators began each day by studiously noting its fluctuations in level. Around blazing campfires log drivers endlessly debated the ebb and flow of its current. By building dams as assiduously as the all but eliminated beaver, by blasting boulders and constructing booms the lumber men made each mile of the St. Croix's 165 mile length serve the purpose of delivering logs to mill and market. Like the tentacles of some great industrial monster the lumber industry probed, damned and controlled even the remotest of the river's tributaries, bending their wild reaches to its commercial purpose. The early lumbermen more than doubled the natural transportation capacity of the St. Croix watershed to 330 miles of water capable of carrying logs to market. When the industry expanded further in the wake of the Civil War more splash dams and stream improvements brought the size of the St. Croix system to a staggering 820 miles of useable waterway. The St. Croix was more than a logging river. For better than a half century, when the ice went out each spring, from its headwaters to Stillwater, it became a river of pine. [4]

Figure 12. Snake River Valley Fur Trade

Sites.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

From Fur Trade to Fir Trade

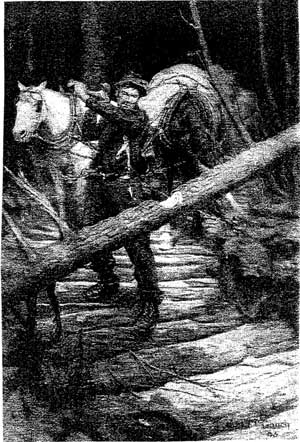

Fur traders, as businessmen familiar with the region and its resources, seemed to be in an excellent position to profit from the rising market for lumber in the 1830s and 1840s. But turning the opportunity into an actuality proved frustratingly difficult. Some traders like Joseph Duchene, or as he was known to all, La Prairie, who had come to the valley as a young man to work for the Northwest Company, were too old by the 1830s to take up a new line of trade. After working for many years for the American Fur Company in the St. Croix valley, Duchene lived his last days near Pokegama Lake. He suffered from poor eyesight and was known to the Chippewa as Mushkdewinini, "the old blind prairie man." Duchene was cared for in those last years by his son-in-law, Thomas Connor, another Nor'Wester who was disinclined to pursue the opportunities offered by the logging boom. Connor operated a trading post on the St. Croix River, at the mouth of Goose Creek; content to continue trading with the Chippewa, and watching the pine float past his door. The Warren and Cadotte families that had so long controlled the trade of the valley from Lake Superior struggled to make the transition to logging. Lyman Warren saw the handwriting on the wall in 1838 when he left the American Fur Company. Leaving the Lake Superior country he settled on the Chippewa River, near the falls and established a sawmill. He was, however, struck with illness in 1847 and he died before becoming deeply involved with logging. His son William W. Warren was the best educated of the new generation. He was a young man with a scholarly disposition and weak health. He died in 1853 at the age of twenty-eight, after completing his manuscript history of the Chippewa people. [5]

Those fur traders who were in a position to profit from logging were men with trade contacts with the downriver towns that comprised the market for St. Croix pine. Logs unlike furs could not be carried over the Brule portage to Lake Superior. The bulky commodity had to follow the dictates of gravity and go south with the river's flow. Fur traders tied to Mackinac like the Cadottes lacked the market and supply contacts to make the transition from furs to logs. Joseph Renville Brown, the less than scrupulous trader who had lived among both the Dakota and Chippewa of the St. Croix had the necessary downriver contacts. He was a classic frontier man on the make, anxious to make his fortune, be it by furs, land, or timber. As early as 1833 Brown had been cutting pine on the upper St. Croix, most of it seems to have been for developing his trading posts and farm, but some may have been sent down to the Mississippi. Certainly by 1836 Brown had begun to log commercially. Located at the current site of Taylor's Falls, Minnesota, Brown had a crew of loggers strip the river flat of timber. He likely had additional logs cut upstream and floated down to the falls. Brown continued to trade with the Chippewa, which may have distracted him from pursuing the logging venture with vigor. Upwards of two hundred thousand feet of pine were cut by his men, but before the bulk of it could be floated down river they were burned in a forest fire. The remainder of the logs was simply abandoned on the riverbank when Brown, with a characteristic sudden change of direction, decided to quit the St. Croix and resume fur trading on the Minnesota River. [6]

Brown's early logging on the St. Croix had been an illegal intrusion on Chippewa land. Indian Agent Lawrence Taliaferro tried to ward off European-Americans cutting pine on Dakota or Chippewa land. But with pine boards selling for sixty dollars per thousand feet in towns like Galena, Illinois, the center of the lead-mining region, the number of people willing to violate the law was great. In 1836, Brown's sometime partner in the fur trade, Joseph Bailly, complained to Congress. "A few years back the labor of a few Lumbering parties operating with whip saws was sufficient to supply the wants of that market, but now that the country is settling with a rapidity unexampled in the history of our country it requires greater supplies." Was it the government's intention, Bailly asked, to let the whole population of the Mississippi valley "suffer for want of Lumber because a few miserable Indians hold the country?" [7]

Even without government sanction fur traders and others attempted to make their own agreements with the Chippewa to secure access to the pinelands of the upper St. Croix. In March 1837, three of the American Fur Company's former lions in the region, William Aitkin, Henry Hastings Sibley, and Lyman Warren brought together a conference of St. Croix and Snake River Chippewa for the purpose of securing a ten year lease on the forests of the upper river. William Dickson tried the same tactic and like the above-mentioned traders, agent Taliaferro foiled him. Men with more modest expectations simply discretely made their way up river with a handful of laborers and after offering gifts to the local Chippewa band, began to cut pine. One Joseph Pitt led one such party to the falls in 1836. He obtained the consent of the Chippewa only to be run off by the Indian agent Lawrence Taliaferro. [8]

Failure to come to terms with the Indians could be quite costly, as John Boyce of St. Louis discovered in 1837. He led eleven men past the falls in the autumn of that year. With logging equipment, six oxen, and a mackinaw boat he pushed up the St. Croix to the vicinity of the Snake River, where he established a logging camp. The Snake River band, which well understood the great value the white man placed on pine lumber, protested Boyce's activities. "Go back where you came from," ordered Little Six, a bandleader backed by more than one hundred of his people. Boyce sought the mediation of the Presbyterian missionaries at Lake Pokegama. They advised him to leave and the Chippewa threatened to prevent Boyce from removing any of the pine. "We have no money for logs; we have no money for land. Logs cannot go," was their firm policy. Boyce persisted in spite of all threats and harassments, although his efforts came to naught in any event. In May, after a winter of logging, Boyce tried to raft his harvest downstream. The Chippewa, in a manner Boyce regarded as menacing, followed the drive. High water and hungry, unpaid, thoroughly dispirited men led to the loss of most of the logs. With the Chippewa looking on Boyce also lost most of his logging equipment when the mackinac boat upset while being lined down the falls. The boat itself was saved when the shrill whistle of the steamboat Palmyra "broke the silence of the Dalles." Aboard were other lumbermen who rendered Boyce assistance saving his boat and recovering some of the logs. Perhaps most important, the steamboat bore the news that the United States Senate had radified the 1837 treaty of session, appeasing the Snake River Chippewa. It was too late, however, for Boyce. The few logs that were recovered and sold did not come close to meeting the expenses of the venture. Pioneer chronicler William Folsom recorded that "Boyce was disgusted and left the country." [9]

The Treaty of 1837 opened the St. Croix valley to European-American occupation and loggers surged into the valley to exploit the new frontier. John Boyce had paid a high penalty for beginning operations prematurely. As did a number of the other lumbermen who were on the river immediately in the wake of the treaty. In September 1837, Franklin Steele and several partners ascended the river in a bark canoe and a scow loaded with supplies and men. They built several cabins at the falls, filed land claims on the best mill sites, and scouted good timberlands up river. Four other groups of lumbermen arrived that fall. Steele's group organized themselves as the St. Croix Falls Lumber Company and construction was begun on a twenty thousand dollar sawmill. They controlled an important waterpower site, but retained inexperienced millwrights and lumbermen. Their mill was not completed until 1842, in part because the site posed considerable construction challenges. Franklin Steele soon sold his share of the company, and the firm fell under the control of absentee owners and men more interested in land speculation than logging. The most important of the former was Caleb Cushing, a prominent Democratic politician in Massachusetts and a veteran United States diplomat. As logging expanded on the St. Croix it became clear that the head of the Dalles was not the best place to locate a mill and subsequent lumbermen elected to drive their logs farther downstream to lower Lake St. Croix. This did not deter Cushing from continuing to make sizable investments in the site and in timberlands upriver, as well as wrangling with his partners in costly lawsuits. The latter worked their way up to the United States Supreme Court. Cushing was not able to establish his control over the company until 1857. By that time the bloom had long since left the bright promise of the falls site. Other towns had been platted and emerged as logging centers. The Polk County Press mocked St. Croix Falls's hopes of being the industrial center of the river. "The ruthless hand of time has made sad ravages, and though the industrious relic hunters might find there a dam by a mill site, they would not find a mill by a dam site." [10]

The ill-fated St. Croix Falls Lumber Company did succeed in making history in its career of failure and misfortune. Quite unintentionally the company caused the first rafts of lumber to be sent down river to St. Louis. In 1843, the company's boom below the falls gave way before high water. The entire corporate stock of logs was borne away on the flood. While this meant the newly completed mill could not cut the lumber, the company could still salvage something if the logs could be caught downstream. John McKusick a young logger just arrived from New England collected about two million feet of logs. These were assembled into rafts of five hundred thousand feet each and floated down the Mississippi to St. Louis. In the years that followed literally thousands of rafts of logs would follow in their wake. John McKusick used the proceeds from his share of that log sale to purchase the machinery for a water-powered mill. That mill was established at Stillwater where it played a major role in making that site, as opposed to St. Croix Falls, the lumber center of the river. [11]

The surest way to making money in this early stage of the logging boom was to keep things simple -- get a crew of men to the upper St. Croix, cut several hundred thousand board feet of trees, drive them over the falls, assemble them into a raft and float them to growing river towns, preferably one not too far south. In May of 1838 Lawrence Taliaferro reported that two hundred men were at work in the pineries of the St. Croix and the Chippewa, by October the number had grown to five hundred. These small-scale operators benefited from what amounted to a free resource. The patchy pine lands of the lower river were not surveyed by the General Land Office until 1847 while the tall timber of the upper river was not mapped until the 1850s, so even if an individual wanted to purchase the land he was logging it would have been impossible. Even preemption claims were not possible on unsurveyed lands in Minnesota until Congress extended that privilege in 1854. With federal land policy making legal purchase impossible and the market clamoring for more lumber, the pioneers of the pineries responded in the best, unscrupulous tradition of the frontier – they took what they needed and damned the consequences. The era of free timber on the lower St. Croix lasted at least a decade, from 1838 to 1848, and on the upper river private fortunes were made off public lands well into the 1850s. [12]

Figure 13. Oxen haul a big pine log to the river

landing. From Harper's Magazine, March, 1860.

Frontier Logging: Life in the Forest

Logging on the St. Croix during the 1840s and 1850s was a primitive, small-scale, frontier enterprise. The size of a logging crew was small -- between ten and fifteen men. Typical was the eleven man team deployed by the ill-fated John Boyce in 1837. That year there were at least five crews operating on the St. Croix. By 1854 this number had swelled to eighty-two crews, twenty-two of whom were established along the Snake River where some of the finest white pine was to be found. Each of the crews included several oxen. In 1837 Boyce had six of the beasts of burden. They were used to drag felled pine from where they were cut to the river landing where they were stacked for transportation in the spring. The early loggers had the advantage of being able to work stands of pine adjacent to the river. Since the logs were only dragged a short distance, a simple wooden travois, called a "go-devil," attached to a single oxen, was the only equipment needed to transport logs. The crews were divided into a few specialized tasks. Most valuable were the choppers, men skilled with using an axe and in making a tree fall where they wanted. They were usually the best-paid men in the crew. Once a pine was felled, the swamper came in and cut off any branches. Another man called the barker peeled off the bark on the underside of the tree, to create a smooth surface for dragging on the snow. Next the chainer connected the oxen to the log and guided it through the drifts to the landing. What may be the location of one of these river landings can be found on the Upper Namekagon River above Hayward, Wisconsin (T40N, R11W, Sec. 14, NE1/4, NE1/4). At the site a ramp was clearly excavated into the bank of the river to allow for the easy sliding of logs into the river. During this early period of logging axes and handspikes were the only tools used. Brute strength and teamwork made up for the lack of technology. After a long day of working in the woods in sub-freezing temperature the men were bone-weary and cold. One contemporary remarked that the "boys" had been "transformed into men like unto Abraham of old" -- the black whiskers of youth having been made "white as the driven snow" by the frost. [13]

Logging camps from this primary, primitive period of the logging frontier are the type most likely to be found within the narrow boundary of the National Scenic Riverway. Camps from this era were built near the banks of the St. Croix and its tributaries although they seldom consisted of more than one or two structures. The men lived and ate in a single shanty constructed of rough logs cut on the site. "Took a look around to see what a camp was," wrote a journalist who visited a logging site on Wood Lake in 1855. "Found it to be about 25 feet square with a roof running almost to the ground. The gables were built up with logs, and no windows. A door opened into the domicile and was secured with a wooden latch." The bunks were aligned under the low hanging eves of the shanty, with the deacon's seat at the foot of each bed. "This is a seat running on both sides of the fire from one end of the camp to the other." In the center of the camp was a great open hearth while "on the roof was a chimney, and the smoke receded from the center to the cavity above without the aid of a back wall." Some of these camps were built without the aid of a single nail, from the materials available on the site. There was no illusion of building for the future, after a winter, or at most two, the buildings were abandoned. Remarkably, only a handful of actual logging camps sites have been identified within the Riverway. In many places archeologists have discovered the outlines of buildings from the mid to late nineteenth century but positive identification is difficult. One possible logging camp sites was identified on the Wisconsin side of the river near the site of Nevers Dam. Until further studies are made it will remain unclear if this site was actually a camp where lumberjacks cut timber or if it was associated with driving logs on the St. Croix. The physical remains found on the southeast bank of the Namekagon River in Sawyer County (T42N, R8W, Sec. 21) are more clearly associated with an early lumber camp. The site consists of the outline of four structures and a depression that likely was the site of a root cellar. Artifacts found at the site included clay pipes and portions of kerosene lamps. Archeologists dated the site as from 1850-1900. According to local tradition the site was known as Doran's Crossing and Lumber Camp. [14]

The biggest challenge to the early lumbermen was supplying their camps. An advance party would be sent up river in the late autumn, usually via a bateau or some other river craft. They would build the shanty and bring in a store of preliminary supplies. Later after the snow fell overland transportation to the camps became possible. Lumbermen maintained a large warehouse in Taylor's Falls that would be stocked by steamboat deliveries during the fall and would serve as the starting place for winter supply sleds. Platted in 1851, the village of Taylors Falls was an important supply center for the logging camps because it stood at the head of steam navigation on the St. Croix. The town's merchants had to literally carve their town out of the trap rock at the foot of the falls of the St. Croix River. Taylors Falls was also a useful supply center because of its locations on the Point Douglas-Superior Military Road. Completed in 1858, this road served loggers by providing partial access to the pineries along the Snake River with tote roads blazed by the lumberjacks branching out from it and leading deep into the forest to the camps. Crude shelters for man and beast were set-up at several spots along the road to provide a safe overnight site for the supply sleds. [15]

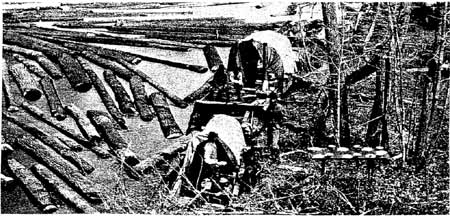

An important stopping place on the Namekagon River was the hamlet of Veazie. Beginning in the 1860s it was a depot for camp supplies and a shelter for teamsters. Located on the river between Trego and Earl, Wisconsin, Veazie was given the name Trout Brook when a post office was established there in 1881. That name did not stick. Everyone called the place Veazie, after William Veazie, the Marine lumberman who built the first structures there. But after the logging camps exhausted the good pine near the Namekagon, they had to be established deeper in the interior and Veazie ceased to be a convenient stopping place and the depot was abandoned. In 1886, William Veazie himself left the St. Croix valley for the thicker forests of Washington State. [16]

Because of the rough track over which the supply sleds had to traverse, the goods they brought were only the bare necessities. These were purchased at a very dear price. The lack of agricultural development along the river in the 1840s and 1850s meant that most of the food had to come from downriver, often from as far away as Illinois or St. Louis. During his first year on the St. Croix, Franklin Steele had to pay four dollars for a barrel of beans, two dollars for a gallon of molasses, eleven dollars for a barrel of flour, and a whopping forty dollars for a single barrel of pork. Those lumbermen who did not send buyers downstream for supplies found it difficult to secure edibles at any price. In 1846 Stephen B. Hanks, a cousin of Abraham Lincoln, purchased supplies for a Stillwater lumberman. In St. Louis he bought several tons of beans, hominy, eggs, and dried apples. On his way up river he stopped in Bellevue, Illinois and secured fifty barrels of flour and several more of whiskey. This still left him short of a critical item–pork. [17]

Pork and beans was fuel that powered the pioneer logger. "Pork and beans are all the go," recorded the visitor to a 1850s camp in the valley. The cook would prepare these in a dutch oven over an open fire in the shanty. "He baked his beans thus wise: a hole made in the earth floor near the fire, was partly filled with live coals and the oven set upon them. In time the lid would be removed and beans would be nicely baked." Stick-to-your-ribs staples such as pork and beans and potatoes, washed down with black tea dominated the menu at breakfast, lunch, and supper. A crew of fourteen men had no trouble devouring ten bushels of beans and six barrels of pork over a season. One lumberjack later joked that when the men awoke they would "tremble and start from the land of dreams to the land of pork and beans." [18]

The demand for local produce by the logging camps on the upper St. Croix provided an opportunity for the Chippewa. With the decline of the fur trade the St. Croix bands had expanded their involvement in agriculture and looked to hunting and gathering to provide new products with which to procure European-American goods. Camp cooks sometimes exchanged maple sugar; wild rice, cranberries, and venison for salted beef, pork, and flour. Yet, these exchanges did not take place on the St. Croix with the same frequency as in the nearby Rum River valley. An early lumberman on the Rum River reported, "I must say that the Indians are very friendly and accommodating in various ways." The eagerness of the Mille Lacs band to trade with lumbermen made that area, in the opinion of the St. Paul Minnesotan, "the most desirable point for lumbering that has yet been discovered in Minnesota." [19]

On the St. Croix relations between the Chippewa and the lumbermen were more strained. This may in part be the result of the persistence of unsavory whiskey traders among the Snake River and St. Croix bands. The St. Croix Chippewa appear to have had fewer surpluses to sell and there were occasional incidents where hungry Indians broke into storehouses or slaughtered lumbermen's oxen. Such disputes led to an 1855 encounter that left two loggers wounded following "outrages perpetrated by the Indians." In March of 1847, loggers turned out enmasse when Henry Rust, who operated a whiskey shack on the lower Snake River, was found shot to death. They buried him, then destroyed his whiskey and burned his trading post. The lumbermen resolved to prevent further such incidents by destroying the whiskey of three other traders in the area. Two Chippewa were charged with the murder and in one of the valley's first trials were found not guilty. The court blamed Rust for his own death since he facilitated the drunkenness that led to his shooting. [20]

A more serious clash occurred in 1864 when two Chippewa shot and killed Oliver Grove and Harry Knight near Pipe Lake, in Polk County, Wisconsin. The incident was a crime of opportunity motivated by a desire to rob the two lumbermen, who had been cruising for timberlands. The bodies of the murdered men were cut into pieces, weighed with rocks, and sunk to the bottom of the lake. After they went missing as many as three hundred loggers participated in a search of the forest. After several months a rumor circulated among the Chippewa that soldiers were on their way to investigate, if necessary, and punish the perpetrators. This led to an unofficial confirmation of the identity of the principle perpetrator. Lumberman James Bracklin, supported by his loggers, took it upon himself to seize the suspect. A tense standoff followed in which Bracklin tried to prevent several hundred Chippewa from retaking the man. Fortunately, there was no further violence. The incident ended when the accused Chippewa shot himself, "fearing the vengeance of the white man." Several hundred dollars and the personal effects of the victims were recovered. [21]

While whites emphasized the murder and robbery aspects of this case, there were other reasons for tension between the lumbermen and the Chippewa. The dams built by loggers to ensure the transport of their winter's cut played havoc with the Indian's use of the river. Large amounts of logs sent down stream on a head of water damaged canoes, swept away fish weirs, and made river travel hazardous. In 1851, Indian Agent John S. Watrous experienced this first hand when a dam at the foot of Cross Lake was opened and his canoe was wrecked and all of his supplies were lost. The prolonged standoff over the fate of the Indian suspected of murder in 1864 was in stark contrast to the 1848 murder of Henry Rust where the two Chippewa suspects turned themselves in for trial. The 1864 standoff occurred at a time when the Chippewa were protesting a dam built on Rice Lake that had raised the water level and drowned the all important wild rice crop. Not only did lumberman James Bracklin refuse to do anything to modify the Rice Lake dam, he set to work that summer on a second dam at Chetek Lake knowing full well this would destroy more Chippewa rice beds. It required considerable restraint on the Chippewa's part for the incident to conclude with only the death of the one suspect. [22]

The potential for conflict with loggers and the abuses of the whiskey traders inclined the United States government to remove the St. Croix bands from their homeland. The Chippewa objected citing the provision of the 1837 Treaty that allowed them to hunt and gather upon the sold lands until they were needed for settlement. "We agreed to sell on the condition that we should not be disturbed for many years," they petitioned the President. After a poorly coordinated attempt to remove the Chippewa in 1851 the government abandoned that policy. Lumbermen and the Chippewa continued to share the river. Unlike in the Mille Lacs region, where lumbermen provided financial compensation to the Chippewa for the flooding of their rice marshes, the St. Croix and its tributaries were manipulated to suit the lumbermen with little concern for the interest of the Chippewas. [23]

Most of the loggers operating in the valley during the mid-nineteenth century had little contact with the Chippewa. They did not journey into the upper river valley until late November or early December, a time when most of the Chippewa had repaired to their family hunting grounds. Men from Maine, with a sprinkling of Germans, Canadians, and Swedes dominated the crews. They were mostly young men, in their twenties or early thirties. "Boys they were," recalled one pioneer from that period, "willing to toil at the most strenuous labor if it brought but a reasonable promise of return." During this pioneer era in logging only a fine line separated the crew from the boss. "Most of the early lumbermen," another early settler recalled, "were young men of limited means who came to better their condition. A man with capital enough to buy a couple of yoke of oxen could get credit for supplies and hire a crew of men and cut a million feet of logs or more in a winter." The result of such opportunity was hundreds of small camps operating independent of one another. The small size of the crews often made them close-knit and very efficient. In 1855, the foreman of a crew on the Groundhouse River, a tributary of the Snake River, wrote back to his hometown newspaper in Maine boasting that his men had put up between two and three million logs in 117 days, a record he challenged any of the eastern crews to match. Men looked out for each other in the conduct of their highly dangerous work and socialized in the crowded quarters after dark. [24]

Card playing, pipe smoking, and occasionally signing were recreations common in the shanty house after meals. "Some sang songs," recorded a journalist visiting a camp in 1855, "and it is but justice to them to say that we were agreeably disappointed in finding some fine singers there. The songs are principally of a love nature and usually to the better feelings of mankind and sympathy." Nils Haugen, a Norwegian immigrant, recalled the camp in which he worked during the winter of 1866-67 as "primitive" but the crew was "clean, and not a cootie or other bug was discovered all winter." He spent his winter evenings reading from the boss's collection of Sir Walter Scott novels. The linkage of lumberjacks and literature was not entirely exceptional. James Johnston, a Canadian immigrant who spent the winter of 1856-57 logging on a branch of the Snake River, was delighted to find in camp a copy of Ivanhoe and a collection of Captain Maryatt novels. Later he "made it a custom to have some book in camp and sometimes at the request of the boys would read aloud while the crew would listen." On one improbable occasion he was reading Jane Eyre to the men who sat in rapt attention as the young orphan Jane was humiliated by one of her teachers. One of the men, who regarded Jane Eyre as "one of God's little lambs," shouted out a curse "from the very bottom on his soul" at the insult to the heroine. The rest of the crew then "broke out in cheers and laughter." [25]

Figure 14. A lumber raft from Harper's Magazine,

March, 1860. Rafts assembled on the St. Croix for transport down the

Mississippi wre often much larger.

Frontier Logging: The Importance of Waterpower

The scale of logging on the St. Croix increased steadily through the 1840s and 1850s. The eight million feet produced by the valley in 1843 was typical of output during the 1840s. By 1855, production had greatly increased to 160 million feet. Less than ten years latter the amount of logs floated down the St. Croix topped two hundred million feet. Logging operations became both larger and more complex. To increase the harvest double camps, with crews of twenty-five to thirty men, became the rule. To move an ever-increasing amount of logs more men were required as river drivers and more and better dams were needed to increase the flow. By 1864, more than $600,000 was invested in forest operations along the St. Croix. The number of men employed in the woods swelled to fourteen hundred loggers, more people than had ever before lived in the valley. Little wonder the Chippewa were forced to yield before the advance of this axe wielding army. [26]

While hundreds of European-Americans flocked to the St. Croix to participate in the logging boom the bulk of the land in the valley was falling into the hands of a small number of men with access to capital. Typical of these was the partnership of veteran Maine lumbermen Isaac Staples and Samuel F. Hersey. Staples was the resident partner who oversaw operations from their Stillwater, Minnesota mill site, while Hersey was the out-of-state investor who used his profits from the Maine woods and capital connections in Massachusetts to purchase extensive pine lands along the St. Croix. Between 1853 and 1864 Hersey, Staples, and Company purchased forty thousand acres of timberland. They were too experienced in the ways of the industry to make all of these purchases for the government minimum of $1.25 per acre. Rather three quarters of their empire was secured much more cheaply through the use of land warrants. These were notes redeemable in public domain land. The federal government offered these to veterans of the Mexican-American War. Of course most veterans did not want to begin life anew on the frontier. Historians have estimated that only one in five hundred veterans cashed in their warrants for land. More commonly the warrants were sold at discount, on an average seventy-five per cent of the value, to real estate speculators. During the early 1850s land sales via warrants outpaced cash sales. By a combination of warrants and cash Hersey, Staples, and Company was able to secure vast tracts of contiguous land. When Knife Lake Township, in Kanabec County was offered for sale in 1859 the firm was able to secure twenty-one of its thirty-six sections. These block purchases were important to economical logging. Access roads and dams, and sometimes even camps, could be reused season after season because of the firm's long-term involvement in the area. [27]

While Hersey, Staples, and Company became the largest single owners of timberland in the valley; there were numerous other eastern born men who established themselves in the industry. The first sawmill at Stillwater was erected in 1844 by a partnership made up of John McKusick from Maine, Elam Greeley of New Hampshire, and Elias McKean of Pennsylvania. Socrates Nelson, another early mill operator in Stillwater, came to the town from Massachusetts as a merchant but soon joined the lumber rush. Daniel Mears another Bay State native followed the same progression from merchant to lumberman, first in St. Croix Falls and later at Hudson, Wisconsin. In 1839, Illinoisan George B. Judd partnered with Walker Orange of Vermont to establish the first mill in the valley at Marine-on-the-St. Croix. William Folsom, who came from Maine to the St. Croix valley in 1845, was also a typical frontier lumberman. In less than a year he went from being a hired hand to part owner of a small mill. Typical of the opportunity that existed in the valley, Folsom was able to establish himself in business simply by filing a preemption claim on a waterpower site on the west bank of the river a few miles above Stillwater. Three other partners provided the capital, while Folsom contributed the site and his labor. After a year working to establish the mill, Folsom sold out to his partners for a cash profit. [28]

In the minds of these first lumbermen waterpower sites were of paramount importance in determining were to locate their mills. Waterpower had historically been the principal forcing driving America's early industry. United States surveyors carrying out the job of locating section lines in the American wilderness were under orders to note all potential waterpower sites. Before the Civil War sawmills on the St. Croix were largely dependent upon a steady, fast flow of water to transform logs into lumber. For this reason St. Croix Falls was considered the prime location for industry in the entire valley and it became a bitter bone of legal contention. Another obviously good mill site was Marine and it, too, became the site of conflicting claims. Unlike St. Croix Falls, however, the partners who established the first mill at Marine quickly dispatched with their rivals. When Orange Walker and his Illinois partners arrived at the site with their milling and logging equipment they found two men camped on the site, ready to contest that had staked first claim to the site. Rather than squabble over the squatters assertion the Illinois partners paid three hundred dollars to establish their clear title to the waterpower site. It was a smart investment and within a few months they had built dwellings for themselves and their workers and erected the first sawmill on the river. An overshot mill with buckets attached to the wheel was built besides a small stream entering the St. Croix. The water wheel powered a heavy, slow-moving muley saw. It produced no more that five thousand feet of lumber per day, but it was the beginning of a revolution on the river. [29]

The lumber produced by the mills still was a bulky product and, therefore, expensive to move to markets located anywhere but downstream. St. Croix mill owners had their cut assembled into rafts that would then be floated to market towns along the Mississippi River. The rafts were carefully sectioned together through the use of large wooden stakes driven into holes augured into the boards. The holes damaged the wood and lessened its market value but they securely kept the raft together. Large oars, forty to fifty feet long at the bow and stern of the raft provided means to steer the makeshift craft. The completed raft might consist of a series of sections, together hundreds, sometimes thousands of feet in length. A steady river current was critical to successfully rafting boards to market. In this sense Lake St. Croix on the Lower River and Lake Pepin, a twenty-seven mile section of the Mississippi just downstream from the St. Croix, was the bane of the raftsman. Broad slack water was prone to heavy winds. When the breeze was in the raft's favor, sails could be put up and the craft could be easily advanced. Head winds could delay a raft for days, with the men helplessly hung up or struggling desperately with line along the muddy bank, trying to pull the raft to a point where the current resumed. The Mississippi's normal steady flow of a mile or two an hour was ideal for rafting, although fast places where a narrowing of the channel or obstructions in the river bed caused rapids to form could be as detrimental to rafting as slack water. The Upper Rapids on the Mississippi consisted of fourteen miles of fast rocky water ending at Rock Island, Illinois. The smaller Lower Rapids near Keokuk, Iowa were less of a challenge but still consisted of twelve miles of dangerous water, very capable of drowning a careless crew and busting up a raft worth thousands of dollars and scattering its boards on hundreds of miles of banks and sloughs. While on smooth water the rafts were kept moving twenty-four hours a day. A trip from the St. Croix to St. Louis, the largest of the downriver markets, would take about three weeks. [30]

Rafts of logs were much more difficult to control than lumber. The logs were larger irregular in shape, and harder to secure into a manageable craft. Both rapids and slack water were more difficult to manage with log rafts, yet skilled pilots could bring the logs down to St. Louis. Log rafting expanded the possibilities for milling St. Croix lumber from sites within the valley to virtually any likely location downstream from the pineries. St. Croix logs were regularly rafted to sawmills in Winona, La Crosse, Rock Island, Keokuk, Quincy, as well as St. Louis. The St. Croix valley's proximity to the unparalleled transportation opportunities offered by the Mississippi River, a virtue shared by the Chippewa River, made these areas extremely attractive to lumbermen during the pioneer phase of logging in the region. Later, in the 1870s, as railroads began to expand in the area, and offer an alternative transportation system, access to the Mississippi became somewhat less important. But during the era before the Civil War, when logging was dominated by the use of waterpower, rafting was the sole means for moving logs and lumber to market. [31]

The reliance of lumbermen on rafting logs and lumber created a strong seasonal labor market for men willing to work on the river. In the early days of the industry an unlikely relationship grew up between the little Illinois town of Albany and the lumbermen of the St. Croix. Located on the Mississippi River across from Clinton, Iowa, the town of Albany produced many of the best pilots on the upper river. Rivermen from Albany took charge of many of the early raft flotillas sent from the valley. Stephen Hanks, who piloted the very first raft of logs from the St. Croix to St. Louis, was from Albany as were all the rivermen in that flotilla. That summer of 1846 Hanks piloted three rafts down to St. Louis, each round trip taking close to thirty days. While the pilots had to be men who knew the river, the crews who manned the sweeps merely needed to be strong and willing to work long hours under the open sky. Scandinavian and Canadian immigrants often took to the rafts when the spring rafting season began. A crew of as many as ten men would be necessary to take a raft south. In rapids at least two men were needed to handle the long oars through powerful current. Between manning the St. Croix boom and downriver rafts the lumber traffic at Stillwater alone gave employment to more than twenty-five hundred men in 1860. [32]

The most vital use of water power was not sawing the logs or shipping the lumber to market, but the transportation of logs from the forests of the upper river to the mills and boom on the lower river. The pine forests of the upper St. Croix would have remained wilderness had the river not been harnessed to drive the winter's cut downstream. Nonetheless log driving was the most expensive, the most difficult, and the most vexing aspect of logging in the St. Croix valley. The main river was blessed with a strong steady current but also with numerous rocky passages that proved to be troublesome chokepoints. Save for the Namekagon, the St. Croix's numerous tributaries were small, winding forest streams with limited flow. Success at moving a winter's cut from the pineries to the mill required a mix of appropriate weather conditions, skillful planning, and exhausting, cold, wet work.

Throughout the winter logging season the wool-clad lumberjacks stacked the pine logs in large piles at a streamside landing. When the ice went out in April, that tributary stream would be used to carry the logs to the main river. Some of these streams were so small that a logger could nearly straddle them with a foot on each bank. The ideal size for a logging stream was for it to be just slightly wider than the longest log at the landing. For streams of such size to move thousands of feet of logs, and even more so for those that were smaller, "improvements" were needed. This meant straightening several ox-bow bends and sometimes removing a few boulders. It was expensive, time-consuming work and the lumbermen always tried to get away with undertaking the most minimal improvements. Their goal was to remove logs from tract of land perhaps on a single occasion, at most for only a few years. They were not interested in investing in long-term commercial improvements. One expense that could seldom be avoided was the construction of dams to raise the water level of the stream in its narrow banks and increase the rate of flow enough to move the bulky logs. Ideally the dam could be a crude, hastily constructed splash dam that could quickly backup a head of water and then be chopped open to release its flow. Frequently, however, a formal dam with a lift gate that could be opened and closed would be required. The cost of a formal dam could be substantial -- from hundreds of dollars during the 1850s and thousands of dollars by the turn of the century. The outlet of a pond or small lake was the ideal site for such a dam, as the lake could be used as a reservoir for the backed up water. A couple of days of high water would usually be enough to clear a landing of its harvest of logs and send the mass down to the St. Croix or one of its major tributaries such as the Snake or the Kettle River. Where small watercourses had to be driven long distances, it was necessary to build an additional dam halfway downstream. When all the logs reached the second impoundment that dam would be opened and the logs surged on with the crest of the flood. [33]

During the early years of logging in the St. Croix valley, the value of even the best pineland was greatly influenced by the location and character of the area's watercourses. Hersey, Staples, and Company, the Stillwater logging giant, made large purchases in Kanabec County, Minnesota with the intention of using the Groundhouse River to carry the logs down to the Snake River. Some of the firm's partners were dubious of this plan. "I trust Genl Hersey before he consents to have any more land entered on the G House [Groundhouse river]," wrote Dudley C. Hall, "will be satisfied himself, as to the capacity of that river for driving logs." During the winter of 1855-56 the company set two teams of oxen and about fifteen men to work logging about halfway up the Groundhouse. A dam was built near the camp, and when spring came, the company tried to drive the winter's cut to the Snake and from there down the St. Croix to Stillwater. But things did not go as planned. The head of water from the dam dissipated before the log drivers could get the bulk of the logs down the torturous stream. Precious weeks went by as the drivers struggled to refloat logs left stranded by the drop in the water level. Partners like Dudley Hall peppered the company's managers with requests for updates on the disastrous drive on the Groundhouse. The delayed drive, according to Hall, was "a thousand times more important than the mill. . .I trust you will. . .get them in if money can do it." Disgusted with the problems on the Groundhouse, Hall plainly stated, "I for one will never give my consent to cut any more logs on that river." [34]

The only thing that prevented the Groundhouse problems from ruining the entire season for Hersey, Staples, and Company was the fact that they had operated camps on other more manageable streams and that harvest gave the mill a modest supply of logs. That year they also operated a camp on the Beaver Brook and another on the Namekagon River. These camps successfully sent their logs down to the St. Croix. Once they reached the main river, however, their logs became mixed with the winter's cut of scores of other lumbermen operating camps on the Sunrise, Kettle, Clam, Tamarack, and Upper St. Croix Rivers. This was a problem that lumbermen in the eastern states had faced before and they transferred their solution to western waters. Every log put into the river was impressed with a distinctive mark hammered into the butt end. To sort out the logs lumbermen working along the river pooled their resources to fund a common retrieval system. Initially this was a simple association in which each lumberman reported how many logs he put into the river. When the mass of timber reached the lower river, it was assembled into rafts and counted. If a lumberman rafted more logs than he put into the river, as often happened, then he owed the others a debit to be paid in cash or logs. The system relied upon honesty and trust and could not survive the expansion of logging during the 1850s. [35]

Figure 15. A primitive water powered sawmill. During the

1850s and 1860s single sash saws were replaced by multiple cutting

surfaces known as gang saws. As gang saws became more popular steam

power replaced water power.

The St. Croix Valley

The formation of the St. Croix Boom Company, chartered by the Minnesota Territory in January 1851 marked the beginning of a new, more sophisticated approach to the management of a common waterway as a conduit for thousands of individually owned logs. The boom company was given the right to capture all logs passing over the falls of the St. Croix, sort them according to the owner's mark, and then give them back to the rightful owners in return for a fee of forty cents per thousand board feet delivered. Initially men from Marine, Osceola, and Taylors Falls dominated the boom company, so they located the collecting pens near those towns. This site retarded the development of the boom company because it was too far upriver to effectively serve loggers on the Apple River. This stream that enters the St. Croix south of Marine drains a large area, reaching deep into the lake country of Polk County, Wisconsin. Loggers were operating along seventy-two miles of improved river and its output in the late 1840s and 1850s was second among St. Croix tributaries only to the Snake River. An even bigger problem with the original site of the boom was that it was inconvenient to Stillwater, Minnesota, the town that emerged during the 1850s as the valley's lumber center. Stillwater mill owners had to pay twice to receive their logs -- once to the boom company for collecting and sorting their logs and then again to the rivermen who organized and floated their logs twenty-one miles downstream to the Stillwater mills. Isaac Staples, a partner in Stillwater's largest mill, was anxious to manage the river to his advantage. His opportunity came in 1856 when the original St. Croix Boom Company went bankrupt. Staples and a group of Stillwater based partners took over the boom for fifty cents on the dollar and relocated its main operations to a site just outside the limits of their town, at the head of Lake St. Croix. Until its demise in 1914 the boom company controlled the upper river, taking charge of every log, making every lumberman pay its fees, bending the St. Croix to its will. [36]

The inspiration for the St. Croix boom had been the efficient organization of log transportation by the citizen's of Oldtown, Maine. Isaac Staples, who had lived in Oldtown, had seen its boom in operation. With an experienced eye he selected a superb location for the new St. Croix boom, a narrow, high-banked stretch of river where the stream was divided into several channels by small islands. The boom itself was made up largely of logs chained end to end, anchored to piles driven into the streambed to form a floating fence. There were a series of these fences that acted as a conduit, leading logs to holding pens. Into these pens went the logs of a particular company. Collected there would be the logs splashed several weeks before into some remote tributary stream in the upper valley, minus those logs lost in back channels or sunk to the bottom of the river. Catwalks were built along the boom, allowing loggers to easily move from one part of the boom to the next. [37]

Very little of the St. Croix Boom has survived. The vast system of log and chain channels are, of course, long gone. What remains, located on the Minnesota shore, are a house used by men who managed and worked on the boom and a barn that was used for storage and animal care. The banks of the river are thickly forested with aspen and birch and suggest the appearance of the area at the time the boom was constructed. The site of the boom has been a National Historic Landmark since 1966. The boom house and barn are listed on the National Register.

The St. Croix boom was the most profitable in the Midwest region. This was partially because the State of Minnesota had written a generous fee into their charter. But just as important was the unique construction of the boom that allowed for the bulk of it to be closed off when the number of logs in the river was low. The boom could be expanded or contracted by opening or closing channels. This meant that during slack periods the boom could operate with only a skeleton crew, holding down labor costs, but maintaining a continuous service for lumbermen. The true measure of the boom's effectiveness, however, was its ability to handle a high volume of logs. In 1853, the river at the head of the boom constituted a solid packed mass for three of four miles. This was a common site during the 1850s and one year the owner of a particularly nimble horse offered "to cross the St. Croix River. . .on horseback, driving his horse over upon the floating saw logs that in some places absolutely covered the face of the stream." By the 1870s the mass of logs waiting sorting during mid-summer stretched for fifteen miles. Hundreds of men worked long hours to sort through the mass and send the logs downstream to waiting mills. But with two to three million feet of lumber to sort for some 150 to 200 different lumber companies the backlogs were inevitable. [38]

The highly profitable boom company in time became a hated, if powerful, influence on the St. Croix. Lumbermen anxious to start milling their winters cut fumed over delays at the boom and resented that they had to dig deep into their pockets to pay the boom for sorting their logs. More irate still were the steamboat men who often found the channel above Stillwater completely blocked with logs. Towns like Taylors Falls, Marine, and Franconia suffered economically as they were shut-off from down river trade. Farmers between Stillwater and Taylors Falls were upset to have a low cost means of shipping their crops to market endangered by the powerful boom company. Those located directly on the river suffered a further indignity when the mass of logs so blocked the river as to cause the stream to over flow its banks and flood their homes and fields. During the 1860s and 1870s, the boom company tried to moderate these problems by constructing a shipping canal on the Wisconsin side of the river that would by-pass the bulk of the boom works. At times the company would furnish teams and wagons so that cargoes could be portaged around the logs. It also made available to travelers its small steamboat positioned above the jam. This willingness to work with people and communities impacted by the scale of logs in the river went far to holding down the volume of discontent. In the end the townspeople and farmers inconvenienced by the boom were forced by the boom's economic importance and Stillwater's political muscle to accept that logs and lumber were crucial to the region's growth. [39]

In 1865, the editor of the Taylors Falls Reporter captured the dependence upon the lumber industry that was gradually settling over the towns, both below and above the boom.

Merchants furnish men who go into the woods to cut the timber, with supplies, and wait the arrival of the logs in market for their pay. Laborers work in the pineries, and eagerly watch the coming of the logs to secure their wages, while their better halves wait until the logs come in, for the minor luxuries, which succeed such occasion. If the water is low business is dull, money is scarce, consequently, Lawyers, Doctors, Editors, Ministers, Office-Holders, &c. have to ‘live on the interest of what they owe,' until better times are here.

Equally as interested in the success or failure of the lumber industry were the farmers of the valley. Providing food and fodder for the lumber camps was the critical local market that made pioneer agricultural activities viable within the valley. As long as the boom company expressed a willingness to try and moderate their interference with river commerce the majority of people within the valley supported transforming the St. Croix into a river of logs. [40]

In latter years the St. Croix Boom Company would be referred to as the "Octopus" because of its power over the river. Yet, in actuality the St. Croix boom had much less power over the river than the boom companies organized by lumbermen in Michigan and Wisconsin. The St. Croix boom only handled logs that came over the falls and had no authority to operate on the upper river. In contrast the Menominee River Boom Company in Michigan not only sorted all logs to reach the boom but it took charge of driving all logs put into that river from its headwaters to the boom near Lake Michigan. The same was true of the famed Tittabawassee Boom Company and the Muskegon Boom Company. Eventually all log driving on the Chippewa River in northwestern Wisconsin was put under the control of a single company. But the St. Croix lumbermen remained determined to control the fate of their logs for as long as possible. An attempt in 1872 to form a company to drive all logs on the St. Croix came to naught when the loggers working in the upper valley could not agree on a fair price to pay. Special log driving companies did successfully operate on the Apple River and the Snake River, but on the upper St. Croix scores of independent loggers resisted the control of a single authority in charge of the river. Frequently lumber companies operating in proximity to one another might band together on a temporary basis to drive their logs to the boom, but these were just short-term alliances. Log driving was the most colorful and adventurous aspect of lumbering and on the St. Croix it remained in the hands of rugged individualists. [41]

Figure 16. A wanigan, the cook boat used on log drives,

tied up at the bank of a log filled stream. From Harper's

Magazine, March, 1860.

Industrial River

The Civil War marked a significant benchmark in the development of the lumber industry in the St. Croix valley. From 1837 to 1865 a pioneer industry gradually took root in the valley and flourished. During this time the role of the various towns in the valley was determined. Marine and St. Croix Falls, which had been so promising during the 1840s, had been forced to take a secondary position as production centers to Stillwater and other towns on Lake St. Croix. Land that had belonged to the Chippewa and Dakota had been acquired by the United States and then hastily transferred to private hands, most of it for the minimum price. Under the Indians the valley had been shared, sometimes quite grudgingly, in common by whole communities, now it had been privatized with the will of a few industrialists shaping the future of the land and the river. The demand for St. Croix lumber grew during the Civil War, in spite of the massive disturbance of military operations on the life and economy of the lower Mississippi valley. Three major developments, each enhanced by Union victory in the war, helped to drive the St. Croix lumber industry in the years after 1865: 1) The settlement of the sparsely treed Great Plains; 2) The expansion of the national rail network which created the conditions for a genuine national lumber market; 3) The industrialization of American life that created both the demand and the means to realize greater lumber production.

The expanded reach and inflated ambition of St. Croix lumbermen had a direct and immediate impact on the character of the river and its tributaries. Between 1849 and 1869, for example, the lumbermen greatly increased the amount of water they needed for log transportation. On the Snake River the river driving company charged with managing the flow of logs expanded the driveable length of the river from fifty miles to eighty miles. The Wood River was expanded from sixteen miles of useable stream to fifty miles. The main branch of the St. Croix itself was expanded from a mere eighty miles to well over one hundred. Just as important were the new tributaries that were damned and channelized to fulfill the needs of loggers. Within a few years of the close of the Civil War lumbermen were driving logs on seventy-five to eighty miles of the numerous side streams, lakes, and branches of the Kettle, Yellow, and Namekagon rivers. Simple forest streams such as the Tamarack and the Totogatic were made navigable for logging, the latter utilized for better than fifty miles of twisting streambed reaching through what is today Burnett, Douglas, Washburn, Sawyer, and Bayfield counties, Wisconsin. Dams and stream clearing teams ensured that no sooner did loggers open to use a small tributary of the St. Croix than they would begin to employ the tributary's tributaries for the same purpose. The main branch of the Kettle River, for example, was used for more than eighty-five miles, deep into the Minnesota wilderness, to within less than twenty-five miles of Lake Superior. Its principal tributaries, the Pine, Willow, and Moose Rivers, hardly capable of floating a canoe today, were used to reach even further into the interior. [42]

The experience of the lumberman Elam Greeley on the Clam River in 1875 is illustrative of the manner in which logging was expanded on the St. Croix's numerous tributaries. Greeley's lumberjacks had made a large cut that winter but by June, when most of the region's harvest had been passed through the boom at Stillwater, his logs were hung up on the Clam River. Greeley ordered his foreman, Andrew McGraw, to put the driving crew to work cutting out a canal eighteen feet wide, twenty-five feet deep and two hundred yards long between Beaver Lake and the river. An additional eighty-foot long canal connected Greeley Lake with the river. Controlling dams were put in where the canals reached the lakes. When the dams were opened and the canals were connected to the lakes the flow of the river was powerfully augmented. On this head of water the lumberjacks were able to drive all of the logs down to the St. Croix River. While the Minneapolis Tribune toasted Greeley as "a most enterprising lumberman," no one recorded what the Chippewa, who had harvested wild rice from the lakeshores for generations, thought of the sudden drop in water levels. [43]

What made this expansion of the log transportation in the valley possible was the increased number and sophistication of the dams constructed by loggers. By 1889, there were between sixty and seventy logging dams within the St. Croix watershed. Small headwaters dams, such as five located on the upper Snake River which cost only between five hundred to two thousand dollars, were typical of the majority of the river improvements. Dams located on the St. Croix or its principal tributaries, however, required considerable engineering skill and a formidable capital investment. In 1871, Isaac Staples invested ten thousand dollars to have a dam built on the St. Croix River just downstream from Upper Lake St. Croix. The dam facilitated the transportation of logs from the Moose River, an area highly prized for the superiority of its pine. Logs sluiced through the dam were assessed a fee to allow Staples to recoup his sizeable investment. Sometimes lumbermen would pool their resources to undertake such construction activities. The Namekagon Improvement Company, for example, was capitalized at twenty-five thousand dollars to operate a logging dam on the main branch of the Namekagon River (a few miles downstream of the current Hayward dam). Typical of the post-Civil War era dams used to control the St. Croix was the twelve foot high Namekagon and Totogatic Dam. It was a four hundred-foot earthen dam anchored by 326 wooden piles driven deep into the streambed. It took as long as eleven months to raise a six-foot head of water. During the time the dam gates were closed it was necessary to station a dam keeper on site to monitor the water level. When the driving season began the dam's three eight-foot sluicing gates would be opened to float the logs down to the Namekagon on the flood. Working under a charter from the state of Wisconsin the company went on to construct seventeen more dams along the tributaries of the upper St. Croix. [44]

The remains of old dams can be seen throughout the St. Croix National Scenic Riverway. The most common remains are those of wing dams or as they were more properly called pier dams, navigation aids built out from the bank into the river that were designed to concentrate the flow of the river and guide logs past potential obstructions. A good example of these works can be found on the Namekagon River near Cable, Wisconsin where the remains of five wing dams are found in the river. The dams are constructed of cobblestone and are ten feet by thirty-five feet in dimension. The Namekagon at this point is shallow and the riverbanks are low and flanked by swampy ground. The pier dams here prevented the logs from meandering into the near by swamps. Another set of pier dams can be found in the St. Croix River a mile north of the Burnett-Polk County line, on the Wisconsin side of the river. The wing dam here is 120 feet by five feet and prevented logs from being hung up against a small island in the river. The remains of larger control dams on the St. Croix and Namekgon have mostly been destroyed to allow for the passage of boats and canoes. This was the fate of a dam on the upper Namekagon just above Hayward, Wisconsin. For many years canoeists were forced to portage around the decaying wood and cribbed rock structure. In the early 1990s, the National Park Service removed most of the dam to allow for the free flow of the river. At the outlet of Pacwawong Lake canoeists pass remains of Pacwawong Dam. In 1990, at the request of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, the National Park Service removed over forty feet of cut logs held together by square spikes that still remain in the river. The Coppermine Dam on the Upper St. Croix also boasts the remains of what was once a gated dam on the river, but here too most of the old logging structure has been removed. [45]

River improvements were not the largest single cost faced by lumbermen but they did represent a formidable portion of the price of doing business. Between 1879 and 1884 lumberman Edwin St. John logged on the Lower Tamarack River, a tributary of the upper St. Croix in Pine County, Minnesota. In order to bring out a total harvest of close to forty million feet of logs St. John had invested $3,000 in camp buildings, $3,000 in road building, $16,000 in horses, oxen and logging equipment, and $5,000 in getting the Lower Tamarack and its tributaries in shape to drive logs. In 1880, the Burnett County Sentinel estimated that to build the thirteen biggest dams in the St. Croix watershed loggers invested a total of $385,614. The most expensive was Big Dam on the upper St. Croix, a twenty-four foot high barrier that cost $94,319. Dam building was not a one-time expense. These works required annual maintenance and usually needed to be rebuilt every ten years. Therefore, a figure of more than one million dollars would be a conservative estimate of how much money lumbermen invested in St. Croix dams between the Civil War and the end of river driving. [46]

Of necessity dam building in the St. Croix watershed became more sophisticated because of environmental changes wrought by the first generation of loggers. Smaller dams beget larger dams in part because the volume of logging also accelerated greatly during the 1860s and 1870s. Another factor was the effect of repeated logging driving on rivers never intended by nature to carry large volumes of logs and a rapid flow of water. The surge of water flowing downstream from logging dams had the effect of eroding natural riverbanks. The Snake River and its tributaries such as the Anna and Knife Rivers, as well as the Upper St. Croix itself, became wider streams after a decade or so of log driving. Yet, while the streams became wider they also became shallower during the bulk of the year when log driving was not taking place. Logging also accelerated siltation. In 1875, for example, the drive on the Snake River was disrupted near Pokegama by sand blocking the channel. More of a problem was the disruption of the natural flow of water downstream by dams closed for long periods to build a head for log driving. The broader shallow rivers, deprived of the protective shade of large pine forests, lost more of their volume to evaporation. An increased investment in dam building was part of the legacy bequeathed by the pioneers to those businessmen who followed them into the pineries. [47]

Figure 17. A logger removes a tree from a tote road. In

the late nineteenth century hundreds of crudely made tote roads were cut

through the forest in order to bring supply wagons to logging camps.

From Outing Magazine, April, 1907.

The Log Drives

Dams made possible the most colorful, dangerous, and difficult phase of logging in the St. Croix valley–the annual spring log drive. In April of every year the best of the lumberjacks were engaged to escort the winter's cut down the small winding headwaters streams to the main branch of the St. Croix and from there to the head of the boom at Stillwater. It was a job where time was of the essence. The long drive had to be completed before the water level, swelled by melted snows, splash dams, and spring rains, fell, leaving valuable logs stranded in water too shallow to float the fallen monarchs of the forest. It was cold, wet work performed by rugged men clad in two or three red woolen shirts and fitted with caulked boots. The most experienced of the rivermen were outfitted with long pikes and they rode the slippery logs in the van of the drive. They were know as "river pigs," a title in which they took perverse pride, and their job was to keep the logs from snagging on sand bars, sharp river bends, or shoals. At obviously difficult spots on the river several men would be stationed throughout the drive to prevent logjams. These men together with those who floated majestically on their logs were known as the "jam crew." The least experienced men were given the coldest and meanest work on the drive, the "sacking crew." This entailed following in the wake of the drive and wading into the shallows to wrestle stranded logs back into the current. Several wooded boats, know as bateaux, sharply pointed at the bow and stern to ward off floating logs, were part of the drive and could be used to transport men to trouble spots as they developed. Even more important was the wanigan, a covered flat-bottomed boat that served as a mobile cook shack. The wanigan provided hot food each morning and evening, although many of the men in the jam crew took their midday meals with them in little back packs they knick-named "nose bags." [48]

The rivermen had to be exceptionally hardy fellows. In what sounds today like the perfect conditions for triggering hypothermia they labored in air temperatures of thirty to forty degrees while regularly plunging into snowmelt waters that were even colder. In 1867 Nils Haugen, a young Norwegian immigrant won a place in the jam crew. He prided himself on his ability to ride a log but on the second day of the drive received a "good wetting." He remembered the "water was icy cold," although his first thought was:

Fortunately no one saw it, so I was saved from being guyed. It was always a matter of merriment to see one fall in. I had on three woolen shirts at the time; I took them off and wrung them out, put them on again, and wore them for the next three weeks, never suffered a cold or other inconvenience from the mishap.

How men coped with the sudden chill of a spill in the river was more important than finding river men who did not fall from their logs. A rookie river driver who had fallen into the Willow River came out of the water cold, badly frightened, and begragled. "I had lost my hat and hand spike and must have been a pitiable looking object." He was sent to warm up by a fire, but after his dunking "I was so scared that I was not much good on the drive." Some men felt that "whiskey helped them to stand the cold water, ice and snow of the early spring," but few foreman allowed their men regular access to strong drink for fear of the consequences to work force discipline. [49]

At night the drive crews would establish a camp on the riverbank. The evening meals generally featured better fare than camp dinners, fried fresh pork was a favorite, although like camp meals the men received as much as they wanted. Nils Haugen recalled:

We slept in tents. The blankets were sewed together so that we were practically under one blanket, the entire crew, the wet and the dry. Steam would rise when the blanket was thrown off.

The workday would begin for the rivermen about three in the morning. This allowed the lumbermen to take full advantage of the water conditions but exposed the crews to considerable danger working among the rolling, grinding logs in pitch-blackness. [50]

River men were paid substantially more than other forest workers because of the hardships and dangers they endured. Young James Johnston recalled his first day trying to ride logs on the Willow River. A branch hanging low over the stream swept him from his precarious perch and he fell "head first into the river." Before he could rise to the surface "some half dozen logs ran over me." Gasping for air he swam for a break in the mass of logs. "When I came up I grabbed the side of a log and, of course, my weight rolled the log toward me and I went down again and a few more logs rolled over me." Only the fact that the current took him to a shallow place in the river saved Johnston's life. An accident recounted in the Stillwater Lumberman in May of 1875 underscores the danger faced by the men working the drives:

Last night Ed. Hurley was brought down from the drive on Clam River in a badly mangled condition. A log rolled on him and broken [sic] his right leg in several places. Dr. Hoyt, of Hudson, was examining him this morning in consultation with city physicians, and found it necessary to amputate his right leg close to the body, which was done this forenoon. It is thought he cannot survive this day. He is a married man and his folks reside here. He is a first class lumberman and will be sadly missed by the river men.

The prospect of earning as much as two dollars and fifty cents per day ensured that there were a steady stream of men willing to take their chances with the rolling, churning logs, and replace Ed Hurely and the other men who went down on the drive. Even the most skilled log riders fell at some point, most trusted their luck that it would not be where the logs could crush or drown them. [51]