|

Scotts Bluff National Monument Nebraska |

|

NPS photo | |

Along the North Platte River in western Nebraska, Scotts Bluff stands out on the landscape—and in the minds of people who have passed this way. Gradually the immense sandstone and siltstone formation is disappearing; wind and water, the forces that built the peaks, are dismantling the rock grain by grain. But to those who have made Scotts Bluff part of their own transitory lives, it seems timeless.

A Sentinel on the Plains

The North Platte River Valley, chiseled through the grassy plains of Nebraska and Wyoming, has been a prairie pathway for at least 10,000 years. In ages past, this corridor led American Indians to places on the river where bison herds stopped to drink. At one spot along the way, a huge bluff towered 800 feet over the valley floor. Its imposing size and adjacent badlands inspired the name Me-a-pa-te, "hill that is hard to go around."

The early 1800s brought other hunters to the plains. Bands of trappers explored the rivers west of the Mississippi in search of "soft gold"—the pelts of fur-bearing animals inhabiting the mountains and valleys. The first whites to happen upon the North Platte route were seven fur company employees on their way back east from the Pacific. They reached Me-a-pa-te on Christmas Day 1812. By the next decade the bluff was a familiar sight to traders in caravans heading toward the Rockies, where for substantial profits they exchanged supplies for furs. According to legend. Rocky Mountain Fur Company clerk Hiram Scott died near Me-a-pa-te in 1828; from then on the bluff had a new name.

Besides supplying fashionable consumers with fur for felt hats, the traders blazed a trail through the mountains to the far West. Their old caravan route became the Oregon Trail, a 2,000-mile roadway to the Pacific Northwest. The rugged topography surrounding Scotts Bluff so intimidated wagoners that the original route bypassed the area well to the south. After 1850, during the peak of the California Gold Rush when emigrant numbers increased dramatically, travelers favored the improved trail through Mitchell Pass, just south of the bluff. It shortened the route by eight miles—about a full day.

In the early 1860s emigrants shared the Oregon Trail with mail and freight carriers, military expeditions, stagecoaches, and Pony Express riders. The rare occasions when travelers encountered Plains Indian war parties led to the establishment of Fort Mitchell in 1864. This fort, 2.5 miles northwest of Scotts Bluff (look for the historical marker on Old Oregon Trail road), was an outpost of Fort Laramie.

By 1867 the Army had abandoned Fort Mitchell, emigrant traffic had waned, and a coast-to-coast telegraph strung through Mitchell Pass had long since replaced the overland mail routes. In 1869 the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads linked up at Promontory, Utah. The Oregon Trail quickly fell into disuse as a transcontinental throughway.

In the next decades Scotts Bluff symbolized the past for one group of settlers and the future for another. The new wave of emigrants arrived not in covered wagons but in railroad cars. And they were not just passing though the plains on their way somewhere else; they came to stay.

Milepost for the Great Migration

For some, the vision of a pioneer's paradise elicited optimism. Others gave up hope for a prosperous life in the East and looked westward for land, wealth, or religious freedom. Whatever the reasons, in the years 1841-1869 some 350,000 people joined wagon trains that rallied at jumping-off points along the Missouri River and set out westward on the California and Oregon trails.

An early advocate of Oregon settlement proclaimed the route "easy, safe, and expeditious." Emigrants found it otherwise. Cramming up to a ton and a half of worldly goods into a 10- by 4-foot canvas-topped wagon—walking alongside to lighten the load for draft animals—travelers faced unpredictable weather, violent winds, quicksand, floods, disease, buffalo stampedes, and, rarely, Indian attacks. Each mile was hard-won.

As the skyline along the Platte River began to reveal its strange scenery, emigrants knew for sure they were in western lands. Certain large formations might loom in the distance for days before the wagon trains reached them. Scotts Bluff was one such sight. Imaginations sparked by the fortress-like vision on the horizon, travelers called it "a Nebraska Gibraltar" or "a Mausoleum which the mightiest of earth might covet." "I could die here," rhapsodized one voyager, "certain of being not far from heaven." Yet few emigrants spent time at the bluff. Wary of being caught on the road when winter arrived, they moved on, grateful at least that a third of the trail lay behind them.

Exploring Scotts Bluff

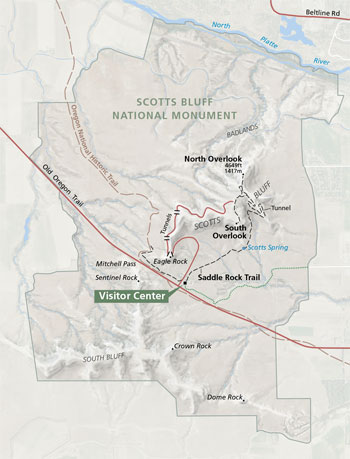

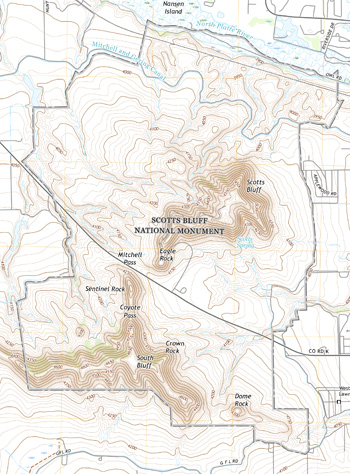

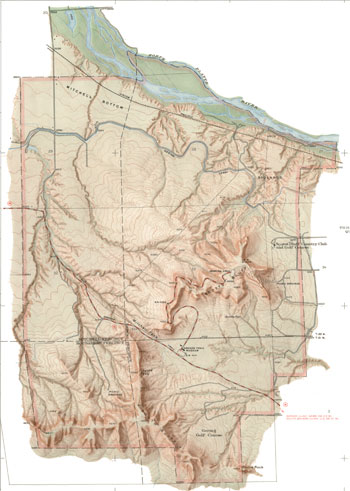

(click for larger maps) |

Five Hundred Feet of Great Plains Past

Scotts Bluff is a remnant of the ancestral high plains—hundreds of feet higher than the present Great Plains—that formed in the continent's interior after uplifting of the Rocky Mountains.

By examining the 10-million-year timeline of Eagle Rock, geologists have determined the origin of the various materials deposited on the ancient plains by wind, water, and occasional volcanic eruptions, as well as the approximate age of each layer.

Scientists have also studied the disappearance of the high plains. Four or five million years ago, the land began to erode faster than new strata were deposited. Some limestone concretions in isolated patches near the surface happened to be more durable than the surrounding material.

Known as cap rock, this stone roof has protected Scotts Bluff so far from the same fate as the adjacent badlands. Thus Scotts Bluff survives as a chapter in human history as well as the remote geological past.

Hardy Inhabitants of the Great American Desert

Nineteenth-century explorer Stephen H. Long called this area the Great American Desert. Because the plains are in the interior of a vast continent, the seasonal variation in temperature is extreme. Air masses heading eastward from the Pacific are thrust upward by the Rockies. The moisture condenses as it rises and cools, falling on the western slopes of the mountains. Instead of rain this region gets strong winds that travel unchecked across the plains. Nature continues to weed out any life unable to adapt to this environment, creating a world of interdependent plants and animals that thrive in the seemingly inhospitable climate.

A look around Scotts Bluff reveals the first sign of prairie: short and mid-length grasses. Emigrants timed their journeys according to the emergence of this vegetation in spring. Too early a start restricted grazing for livestock; a late start exposed travel parties to winter weather in the mountains. Grass varieties may form clumps, like little bluestem, needle-and-thread, and western wheatgrass, or sod like blue grama and buffalo grass. This sod, with its dense, tangled roots, was about the only native material settlers could use to build homes, which they called "soddies." A colorful variety of wildflowers blankets the landscape in spring and summer.

On the northern slopes of the bluff is Rocky Mountain juniper, with its small blue-gray cones or berries, and ponderosa pine. In addition to discouraging soil erosion in the flood-prone, windy climate, most of these plants are food and shelter for other prairie life. Nesting in the stunted trees or on cliffsides are swifts and cliff swallows in summer, and magpies and kestrels year-round. Rabbits, mice, pocket gophers, and prairie dogs live in sod or partially underground, out of sight from predators—fox, badgers, coyotes, and several kinds of snakes. The only poisonous reptile is the prairie rattlesnake, with its diamond-shaped head and unmistakable warning sound.

Highly adaptable herd animals like white-tailed and mule deer still roam the park. Other animals once common on the plains—elk, bison, bighorn sheep, pronghorn, and grizzly bear—have disappeared with the encroachment of human habitation. The population of these animals has rebounded in isolated areas or in protected reserves elsewhere on the plains.

Planning Your Visit

Things To Do

The visitor center has exhibits, information, an audiovisual program,

and a bookstore. Works by photographer and artist William Henry Jackson

(1843-1942) are displayed. Visitor center hours vary by season; call for

information. Service animals are welcome throughout the park.

A short trail leads from the visitor center to where Jackson camped during his trip west in 1866. You can see parts of the original road traveled by pioneers and their covered wagons.

You can reach the top of the bluff by driving the paved road or hiking the Saddle Rock Trail. Both routes are 1.6 miles long and begin at the visitor center. Self-guiding trails on the summit of the bluff extend from the parking area to two overlooks.

For a Safe Visit

Scotts Bluff National Monument preserves 3,000 acres of unusual

landforms and prairie habitat. • Please do not litter, disturb

wildlife, or deface signs or natural features. • Please visit our

website for information on firearms. • Pets must be kept on a

six-foot leash throughout the park. • When driving, stay on

established roads. • Stay on established hiking trails. •

Rattlesnakes in the area are shy but may strike if threatened.

Getting to the Park

From I-80, exit at Kimball, Nebr., and head 45 miles north on Nebr. 71.

From Gering, follow National Park Service signs three miles west to the

park visitor center on Old Oregon Trail.

Source: NPS Brochure (2015)

|

Establishment Scotts Bluff National Monument — December 12, 1919 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A History and Guide: Scotts Bluff National Monument — Landmark on the Overland Trails (Dean Knudsen, undated)

"A Nebraska Gibraltar": Historic Resource Study, Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska (Emily Greenwald, 2012)

Acoustic Monitoring Report: Scotts Bluff National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/NSNS/NRR—2016/1271 (Jacob R. Job, August 2016)

An Administrative History, 1960-1983: Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska (Ron Cockrell, May 1983, rev. November 1983)

An Eye for History: The Paintings of William Henry Jackson (Dean Knudsen, 1997)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring for Scotts Bluff National Monument: Annual Status Report 1998 (William M. Rizzo, February 2000)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring for Scotts Bluff National Monument: Annual Status Report 1999 (William M. Rizzo, January 2001)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: Status Report 1999-2000 (David G. Peitz, May 2001)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: Status Report 2001 NPS Natural Resource (David G. Peitz, April 2002)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: Annual Status Report 2002 (J. Tyler Cribbs, December 2, 2002)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: Annual Status Report 2003 (J. Tyler Cribbs, August 7, 2003)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: Annual Status Report 2004 (J. Tyler Cribbs, April 28, 2005)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: Annual Status Report 2005 (J. Tyler Cribbs, November 4, 2005)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: Annual Status Report 2006 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2006/020 (Brittany A. Hummel, J. Tyler Cribbs and David G. Peitz, August 2006)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: Annual Status Report 2007 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2007/032 (David G. Peitz and J. Tyler Cribbs, September 2007)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: Annual Status Report 2008 (David G. Peitz and J. Tyler Cribbs, August 2008)

Black-Tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: A Comprehensive Report 1995-2009 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2010/309 (Lloyd W. Morrison, Ashley D. Dunkle and David G. Peitz, April 2010)

Black-tailed Prairie Dog Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: 2010-2013 Multiyear Report (Stephen K. Wilson, Marcia H. Wilson and Angela R. Jarding, November 2013)

Cultural Landscape Report and Environmental Assessment, Scotts Bluff National Monument (June 2017)

Foundation Document, Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska (August 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska (January 2015)

General Management Plan, Scotts Bluff National Monument (1998)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Scotts Bluff National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2009/085 (J. Graham, June 2009)

Geologic History of Scotts Bluff National Monument University of Nebraska-Lincoln Educational Circular No. 3 (Roger K. Pabian and James B. Swinehart II, February 1979)

History of Scotts Bluff National Monument (Earl R. Harris, ©Oregon Trail Museum Association, 1962)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Scotts Bluff National Monument (June 2008)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Scotts Bluff National Monument (David Arbogast, March 29, 1976; Designation: October 15, 1996)

Scotts Bluff National Monument (nomination update) (Natalie K. Perrin, Emily Greenwald and Joshua Pollarine, October 24, 2012; Designation: October 15, 1996)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Scotts Bluff National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SCBL/NRR-2018/1682 (Reilly R. Dibner, Nicole Korfanta and Gary Beauvais, July 2018)

Oregon Trail Ruts Landscape Study and Environmental Assessment (Mundus Bishop Design, Inc. and ERO Resource Corporation, December 2010)

Outline of the Geology and Paleontology of Scotts Bluff National Monument (HTML edition) Field Division of Education (William L. Effinger, 1934)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring Protocol for the Northern Great Plains I&M Network Version 1.01 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NGPN/NRR-2012/489 (Amy J. Symstad, Robert A. Gitzen, Cody L. Wienk, Michael R. Bynum, Daniel J. Swanson, Andy D. Thorstenson and Kara J. Paintner-Green, February 2012)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring for Scotts Bluff National Monument

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring: 2011 Annual Report, Scotts Bluff National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NGPN/NRTR—2011/519 (Isabel W. Ashton, Michael Prowatzke, Michael R. Bynum, Tim Shepherd, Stephen K. Wilson and Kara Paintner-Green, December 2011)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring for Scotts Bluff National Monument: 2012 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NGPN/NRTR—2012/647(Isabel W. Ashton, Michael Prowatzke and Stephen K. Wilson, December 2012)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring in Scotts Bluff National Monument: 2013 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NGPN/NRDS—2013/570 (Isabel W. Ashton and Michael Prowatzke, October 2013)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring for Scotts Bluff National Monument: 2014 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NGPN/NRDS—2015/764 (Michael Prowatzke and Stephen K. Wilson, February 2015)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring for Scotts Bluff National Monument: 2011-2015 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NGPN/NRR—2016/1145 (Isabel W. Ashton and Christopher J. Davis, March 2016)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring for Scotts Bluff National Monument: 2016 Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NGPN/NRDS—2016/1076 (Molly B. Davis and Daniel J. Swanson, December 2016)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring for Scotts Bluff National Monument: 2017 Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NGPN/NRDS—2018/1149 (Ryan M. Manuel, February 2018)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument: 2018 Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/NGPN/NRDS—2019/1213 (Isabel W. Ashton, Daniel J. Swanson and Christopher J. Davis, March 2019)

Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska: Historic Handbook No. 28 (HTML edition) (Merrill J. Mattes, 1958, reprint 1961)

Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska: Historic Handbook No. 28 (Merrill J. Mattes, 1958, revised 1983)

Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska: Historic Handbook No. 28 (Merrill J. Mattes, 1958, revised 1992)

Shaded Relief Map: Scotts Bluff National Monument, NE Scale: 1:15,000 (USGS, 1960)

Soil Survey of Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska (2013)

Status Report of Vegetation Community Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument and Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (Alicia Sasseen and Mike DeBacker, May 2005)

Terrestrial Vertebrates of Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska (Mike K. Cox and William L. Franklin, extract from Great Basin Naturalist, Vol. 49 No. 4, 1989)

The Fire History of Scotts Bluff National Monument (Kyle J. Wendtland and Jerrold L. Dodd, extract from Proceedings of the Twelfth North American Prairie Conference, 1990)

The History of Scotts Bluff, Nebraska (HTML edition) Field Division of Education (Donald D. Brand, 1934)

The Lichens of Scotts Bluff National Monument and Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (Clifford M. Wetmore, April 1998)

The William H. Jackson Memorial Wing at Scotts Bluff National Monument (Harry B. Robinson, extract from Nebraska History, Vol. 31, 1950, ©Nebraska State Historical Society)

Trail Development Plan and Environmental Assessment, Scotts Bluff National Monument (July 2013)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument, Nebraska: 1997-2009 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2010/364 (Kevin M. James, August 2010)

White-Nose Syndrome Surveillance Across Northern Great Plains National Park Units: 2018 Interim Report (Ian Abernethy, August 2018)

scbl/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025