|

POSSIBILITIES OF SHELTERBELT PLANTING IN THE PLAINS REGION

|

|

Section 13.—NATIVE VEGETATION OF THE REGION

By J. M. AIKMAN, botanist, Lakes States Forest Experiment Station, Forest Service

CONTENTS

The grassland

The true prairie

The mixed prairie

The short-grass plains

Native tree and shrub communities of the shelterbelt zone

Species and varieties

Distribution of important species and subtypes

Relative ecological importance of species

Composition of tree and shrub communities

Adaptation of native trees and shrubs to shelterbelt planting

Reaction of trees and shrubs to dry conditions: ecotypes

Characteristics of trees growing under xeric conditions

The adaptation of trees and shrubs to alkali

THE GRASSLAND

Before the advent of the plow, grasses prevailed throughout the central portion of North America, with all other vegetative types as minor associates. The displacement of much of the grass in favor of field crops that has since occurred has not altered the essential character of the region.

The grassland formation of the central United States extends westward to the Rocky Mountains from a line running through central Minnesota and Iowa, along the eastern boundary of Kansas, and southward to the Gulf of Mexico.

This extensive plant community may be divided throughout its length from north to south into two almost equal-sized units, corresponding to its naturally dominant types—the prairie on the east, and the short-grass plains on the west. The two important factors which seem to account for this division are simply the amount of precipitation (rain and snowfall), and the proportion of this moisture that is left available to vegetation as against losses through evaporation, run-off, and colloidal adsorption or binding of moisture by the soil. The tall or prairie grasses require a combination of these two factors (such as occurs to the eastward) which makes for a relatively high available moisture content in the soil for a relatively long time through spring and summer; whereas the short grasses are adapted to the more difficult moisture situation that exists to the west.

There is, of course, no definite dividing line between the two plant communities, but rather a north-south zone upon which precipitation, decreasing generally from east to west, occurs in just the requisite marginal amounts to insure the growth of both tall and short grasses in association or mixture; this association of plants may occur as a commingling of individuals or of limited tracts or patches, as determined by local variations of soil.

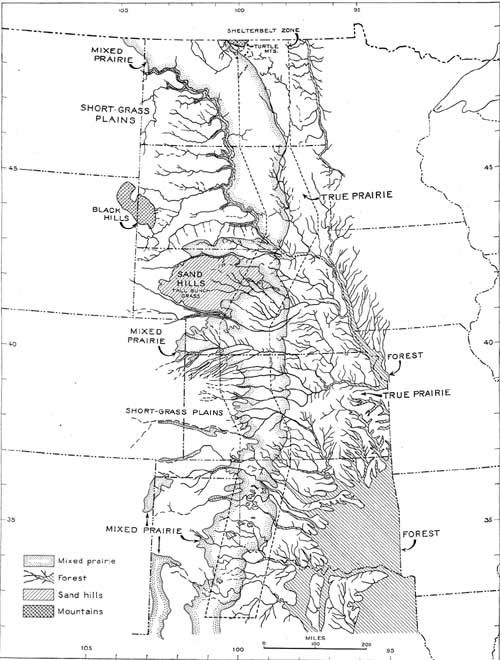

The boundaries of this mixed-prairie zone, like those of all such natural groupings, are irregular. Within its confines the soils vary from clay or silt through a series of loams to pure sand, either fine or coarse, with the silt or loams predominating; but its western border is deeply enfolded by extensions of the more continuous heavy western soils—the typically or exclusively short-grass country. The map (fig. 76) plainly shows this feature. Its eastern border is somewhat more regular, because soil differences are to some extent equalized as climatic factors become more favorable.

The determination of the general boundaries of the mixed prairie zone was an important factor in the final location of the shelterbelt zone, which was to be placed far enough west to protect areas of predominantly agricultural land, and yet not too far to insure success in growing trees. While there is a higher percentage of farm land in areas farther east the mixed prairie zone represents the westward extent, in the central region, of land which may be considered predominantly actual or potential farm land—even though a satisfactory land-use program might reduce to some extent the present farm acreage. At the same time, the presence of well-established tall grasses in the native grassland cover indicates a depth of water penetration much more favorable for the growth of shelterbelts than the shallow depth of water penetration in the short-grass plains bordering the mixed prairie on the west.

The shelterbelt zone boundaries as now delimited have been superposed on the grassland map (fig. 76). Their generally close correlation with the mixed prairie zone is evident.

DEMONSTRATED SHELTERBELT POSSIBILITIES

|

| FIGURE 74.—No apparent encouragement to tree growth in this sandhill section of Nebraska, but a type of site proved by actual experiment to be well suited for forest planting. These low, stabilized sand hills are covered, somewhat sparsely, with prairie grasses, prairie beardgrass. and porcupine grass. Near Rose, Nebr., in northern Loup County. (See text, p. 102.) (F298265) |

|

| FIGURE 75.—An illustration of tree-growing possibilities in the shelterbelt zone. White spruce and ponderosa pine growing without irrigation at the Northern Great Plains Field Station, Mandan, N. Dak.; height, 24 to 30 feet. (F295446) (See text, p. 162.) |

|

| FIGURE 76.—Principal vegetative zones of the prairie-plains region. (click on image for a PDF version) |

THE TRUE PRAIRIE

Because of the narrowness of the mixed prairie zone in several places, portions of the prairie fall within the shelterbelt zone. While these are true prairie sites, the sparse habit of growth of their grasses is more or less similar to the typical bunch-grass habit of tall-grass components of the-mixed prairie.

In the present discussion only this western border of the prairie, included in the shelter-belt area, is considered. The chief prairie dominants along this border in North Dakota and the northern half of South Dakota are slender wheatgrass, Agropyron pauciflorum (Schwein.) Hitchc., (with some blue-stem, A. smithii Rydb., invading from the southwest) and porcupine grass, Stipa spartea Trin., (with needle-and-thread, Stipa comata Trin. and Rupr., invading from the west). Other species, the first of which in some places assumes a role of dominance, are prairie beardgrass, Andropogon scoparius Michx.; side-oats grama, Bouteloua curtipendula (Michx.) Torr.; junegrass, Koeleria cristata (L.) Pers.; prairie dropseed, Sporobolus heterolepis Gray; and blue-joint turkeyfoot, Andropogon furcatus Muhl.48 This cover of grasses uses all of the available moisture of the soil by the middle of the summer, in the more favorable years making a later growth; but differs from the grassland types farther east in being often limited by drought. The growing season is of sufficient length however to insure a permanent tall-grass cover of sufficient density to prevent the invasion of short grasses. Although the soil is chiefly of a heavy type, a yearly rainfall of 18 to 22 inches, with a low rate of evaporation, insures survival of the tall grasses, and also of adapted trees if competition of native vegetation is removed.

48Nomenclature of the grasses follows HITCHCOCK, A. S.: MANUAL OF THE GRASSES OF THE UNITED STATES. U. S. Dept. Agr. Misc. Pub. 200, 1040 pp., illus. 1935.

The chief dominants of that portion of the prairie from central South Dakota to northeastern Nebraska Which is included in the shelterbelt zone are prairie beardgrass and porcupine grass (with needle-and-thread invading from the west). Wheatgrass and bluestem may be dominant in certain localities. Prairie beardgrass occupies the most favorable sites and bluestem the least favorable. Important subdominants are side-oats grama, prairie dropseed, junegrass, and bluejoint turkeyfoot.49

49WEAVER, J. E., and FITZPATRICK, T. J. THE PRAIRIE. Ecological Monog. 4: 111-295. 1934.

The annual rainfall for this region ranges from 22 to 26 inches. The northern part of the region in east central South Dakota, with a rainfall of only 22 inches and with an increase in evaporation over that of the North Dakota section, is less favorable to the growth of prairie grasses than the other included prairie areas. These conditions are further accentuated by the presence of some heavy, unfavorable soils.

In the discontinuous narrow strip of prairie occurring in the shelterbelt zone in southern Kansas and Oklahoma, prairie beardgrass is the chief dominant. Another of the silver beardgrasses, Andropogon saccharoides Swartz, is a codominant. Other important species of the true prairie are bluestem and a longleaf grass, Sporobolus asper (Michx.) Kunth.

The tall prairie grasses, porcupine grass and june-grass, are here found, in scattered bunches, only in the most mature and well-established portions of the prairie. On deep sandy soil bluejoint turkeyfoot, Andropogon furcatus Muhl., and turkeyfoot, A. hallii Hack, are important. The annual rainfall of the prairie here is 26 to 28 inches. If correction for increased evaporation in the south is made by subtracting 6 inches from these figures, they still compare favorably with the rainfall of 18 inches for the western border of the prairie in northern North Dakota. Here, as elsewhere in this strip, there is sufficient moisture to insure survival of true prairie grasses and of properly adapted trees, although after mid-summer there is usually a deficiency of moisture for continued growth.

THE MIXED PRAIRIE

The western boundary of the mixed prairie may be described as a line (fig. 76) east of which sufficient rain falls and penetrates the soil to wet it periodically to a depth varying from 24 to 30 inches. Plants whose roots penetrate the soil to a depth of 24 inches or more obtain moisture for sustained growth for a period of at least 212 months each year, even in drought years. The presence of a permanent tallgrass population is thus insured. The space between these bunches of prairie grasses is occupied by short grasses. On typical upland soil west of the area thus defined, a periodic shortage of water even at a depth of 18 inches precludes the maintenance of a definite permanent tall-grass population within the short-grass cover.

The eastern boundary of the mixed prairie is a line west of which prairie grasses, which assume a bunch-grass habit because of a shortage of available soil moisture, no longer entirely dominate the area but share dominance with short grasses which become permanently established. There are, however, several isolated areas of heavy impervious soil, as those east of the Missouri River in North Dakota and South Dakota from Bismarck to Chamberlain, and those in southern Gosper, Phelps, Kearney, and Adams Counties and in northern Harlan and Franklin Counties in Nebraska, where almost no permanent establishment of the true prairie-grass components of the mixed prairie occurs; their absence in the eastern part of these areas may, to some extent, be attributed to severe grazing.

The depth of penetration of roots in the mixed prairie zone would seem to insure the establishment in the more favorable soils of tree species especially adapted to xeric conditions. Most of the trees within shelterbelts in this zone have been able to extend their roots to a considerably greater depth than 30 inches, especially under conditions which, in the regular addition of duff to the soil and the collection of additional snow by the trees and shrubs, to any extent simulate forest conditions.

THE SHORT-GRASS PLAINS

To the west of the area just described lie the vast plains of the short-grass country. The adaptation of the short grasses to the heavy soils and light precipitation of this region (and to similar soils in the mixed prairie region) is quite definite. In the heavy, fine-textured soils, percolation of moisture is slow and limited in depth, and there is a high percentage of run off, especially of the heavier rains, so that for months or years the subsoil may remain dry. The short grasses make fullest use of the topsoil moisture. Their root systems, fibrous and shallow, almost completely cover the area, taking up the small amount of available water in a limited time, and their season's growth and reproductive processes are completed in a few weeks.

The most important dominant of the entire short-grass plains community (association) (fig. 76) is blue grama, Bouteloua gracilis (H. B. K.) Lag. In the central and eastern part of the Plains, from southern South Dakota southward, buffalo grass, Buchloe dactyloides (Nutt.) Engelm., is associated with blue grama. In well-developed short-grass plains, the cover is short and has the smooth appearance of a closely grazed pasture.50 Taller grasses, as three-awn, Aristida sp., and herbs are more abundant on the eastern border of the Plains, but even here the role of the tall-grass constituents, because of the shallowness of moisture penetration, is not important and permanent enough for the community to be considered mixed prairie. Because of the complete occupation of the top few inches of soil by the fine, fibrous roots of the blue grama and buffalo grass, these grasses are shown to be the true dominants of the community.

50SCHANTZ. H. L. THE NATURAL VEGETATION OF THE GREAT PLAINS REGION, Ann. Assoc. Amer. Geogr. 13: 81-107. 1923.

NATIVE TREE AND SHRUB COMMUNITIES OF THE SHELTERBELT ZONE

Within the shelterbelt zone native trees and shrubs are found growing in considerable numbers, despite the disadvantages of a typically grassland climate. Their presence, bordering stream courses and dry runs, in ravines and in potholes, may be attributed to the protection afforded against excessive evaporation as well as to the additional water supply available in these situations. Such forested areas forecast the general advance of woodland should the climate become wetter, and they suggest the entire feasibility of shelterbelt growing under proper methods of species selection, site preparation, and water conservation such as are contemplated.

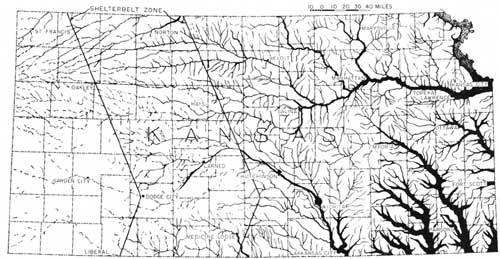

Irregular topography is the chief factor affecting reduction of the evaporating stress of the atmosphere, although the presence of the trees and shrubs themselves affects the rate of evaporation in the immediate vicinity and lessens the net moisture demand per individual. A typical distribution of these woody plants in the grassland formation as it occurs in one State (Kansas) is shown in figure 77.

|

| FIGURE 77.—Typical distribution of trees and shrubs bordering stream courses in the grassland formation (Kansas). (click on image for a PDF version) |

SPECIES AND VARIETIES

In a preliminary survey of 11 weeks' duration in the summer and fall of 1934, collections of many plants were made at 115 separate stations, chiefly within the shelterbelt zone, but also in areas adjacent to the zone along both the eastern and western boundaries, and in many other locations. It is proposed that the collected specimens will be mounted and lodged in a permanent collection. For the present, this collection is to be maintained at the Lake States Forest Experiment Station at St. Paul, Minn.

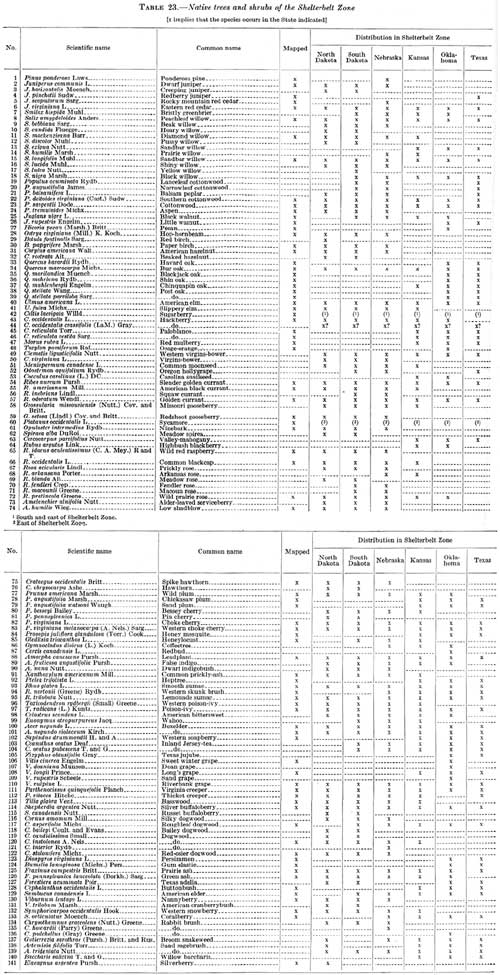

Table 23 is a list of the species and varieties of trees and shrubs of the shelterbelt zone, which may be considered complete except in the minor respects to be noted later. It includes 141 species and varieties. The list was compiled from the collections of trees and shrubs in the herbaria of the State colleges and universities of the States in which the shelterbelt zone is located and from the collection list of the author. All specific and varietal names were included except those concerning which there is considerable controversy.

TABLE 23.—Native trees and shrubs of the Shelterbelt Zone.

(click on image for a PDF version)

Nomenclature of tree species is after Sudworth's Check List of the Forest Trees of the United States. The scientific names of trees not included in this list and of the shrubs were determined by the author after an examination of the specimens and existing lists of specimens prepared by workers in the several States. General keys used in this examination were Gray's Manual of Botany, seventh edition, Rydberg's Flora of the Prairie and Plains, and Coulter and Nelson's New Manual of Rocky Mountain Botany. In each case the name of the authority is included in order that synonyms may be determined. The common names are from the above sources, but in case of conflict the author selected the common name which seemed to be in most general use.

It was attempted, by the removal of specimens from one herbarium to another for comparison, to make the classification of species uniform for the composite list. Specimens which had been identified by authorities in different groups were given especial attention in this comparison. In some instances the specimens in a herbarium, were reclassified by the author and the results tabulated under the new name decided upon. Assistance was obtained from the curators of the several herbaria in this evaluation and comparison, but the author must take full responsibility for the final results.

Data of distribution in the shelterbelt zone by States are included in the table. A species or variety is checked for a given State if it occurs at any place within the shelterbelt zone in that State. Table 23 may be used as a reference list for all scientific and common names of trees and shrubs occurring herein after.

This list of 141 trees and shrubs, compiled from the collections studied, does not include all species and varieties that have been reported for the zone area. Such a list has, however, been compiled; it contains 173 names. Some of the names included in the manuals as of plants occurring in the area are names of varieties which are not recognized in the above list; other names are of plants of very sparse or doubtful occurrence; a few, doubtless, are of plants which may be added to the above list after a more careful survey has been made, for which purpose a collecting trip was definitely planned for the spring and summer of 1935.

DISTRIBUTION OF IMPORTANT SPECIES AND SUBTYPES

The origin of the species of trees and shrubs found within the area may be traced easily. More than half of them are constituents of two divisions of the deciduous forest formation of eastern United States, namely, the central hardwoods and the southern hardwoods. Their invasion into the zone has followed up the main streams and tributaries from the east. The other important movement of species has been eastward from the Rocky Mountain forest formation through the central and the southern Rocky Mountain forests.

Maps showing the extent of the entire grassland distribution of the 71 trees and shrubs of most common occurrence in the shelterbelt zone have been prepared. These maps are based on distribution data and collections obtained in the 1934 preliminary botanical survey of the shelterbelt area, the findings of which were compared with published and unpublished reports on distribution made by several investigators in the area and further checked by a study of the collection points of specimens in the herbaria of State colleges and universities of the States in which the shelterbelt zone occurs.

There are four trees which occur throughout the entire area—sandbar willow, cottonwood, boxelder, and choke cherry. In mapping cottonwood, no distinction was made between Populus deltoides virginiana (Cast.) Sudw. and P. sargentii Dode. Boxelder, Acer negundo L., and the western variety, A. negundo violaceum Kirch., were mapped together, as were choke cherry, Prunus virginiana L., and western choke cherry, P. virginiana melanocarpa (A. Nels.) Sarg. Since no two investigators seem to agree as to the proper distinction between the eastern and western forms of each of these three trees it is found impossible to map separate distributions for any of the forms with any degree of satisfaction. Separation of the two species of golden currant, Ribes aureum Pursh. and R. odoratum Wendl., is easier, but the overlapping of the distribution of the two species and their similar habitat requirements make it advisable to combine their distribution.

One shrub, the golden currant, one shrubby vine, poison-ivy, and one vine, the riverbank grape, are distributed over the entire zone.

Almost complete for the entire area are the distributions of six trees—eastern red cedar, peachleaf willow, American elm, hackberry, green ash and prairie ash combined, and the wild plum. The northeastward extent of the first, the southward extent of the second, the westward extent of the next two, and the southwestward extent of the last two are so indefinite that their distribution over the area might well be considered complete. Green ash and its westward form, the prairie ash, because of difficulty of separation, have been mapped as one species.

RELATIVE ECOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF SPECIES

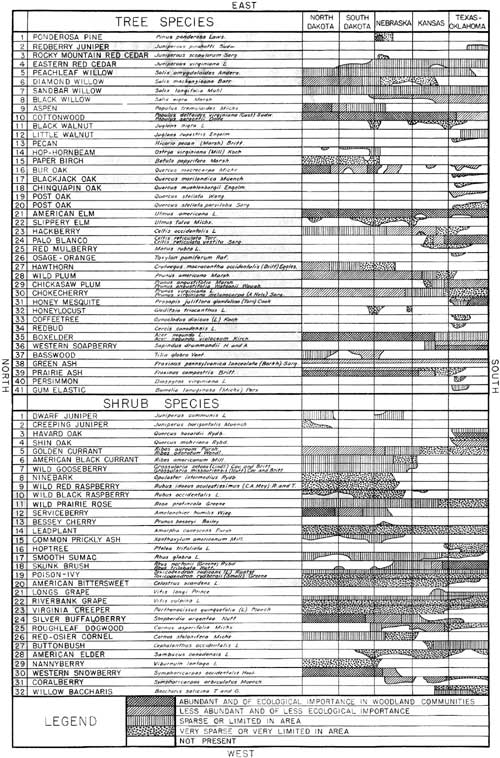

A chart has been prepared representing graphically the occurrence and the ecological value of species of native trees and shrubs in the shelterbelt zone (fig. 78). Each of the strips running crosswise of the page represents the shelterbelt zone, with divisions showing the portion of the zone in the several States. The whole chart, and consequently each strip, is oriented geographically: Top, east; left side, north. Absence of a species from any portion of the belt is designated by a blank space, and its presence, together with its relative importance ecologically, is indicated by one of four different hatchings in the proper space. Thus each strip is a species-ecology map in miniature.

|

| FIGURE 78.—Ecological value of species and varieties of trees and shrubs in native woodland communities in the shelterbelt zone. (click on image for a PDF version) |

A species is given the highest rating (indicated by double crosshatching) if it is found in sufficient abundance to influence the habitat value of the site in which it occurs, provided that the type of site in which it is found is common throughout the area designated. In general, those species which occur in a wider variety of sites, if at all abundant in the average site, rank higher than those which are more specific in habitat requirements. Greater abundance of a species in sites of a particular type may, however, compensate to some extent for its lack of distribution in different types of sites, and vice versa. Shrubs and trees have been represented separately in the chart.

Of the 73 trees and shrubs considered of ecological importance within the shelterbelt area and included in the chart, 40 are found in the belt in North Dakota, 43 in South Dakota, 49 in Nebraska, 41 in Kansas, and 50 in Oklahoma and Texas. The westward extension of nine species of southern trees and shrubs into the zone region only as far as the Oklahoma and Texas portion accounts for the increased number in those States. Favorable conditions presented by the sand hill section probably account for the fact that species extend from all directions into Nebraska, giving it the second highest number. Species from northern Nebraska continue along the Missouri River into southern South Dakota.

Computation of results in terms of number of species entirely covering the shelterbelt zone in the five State divisions of the belt gives the following figures: North Dakota, 34 species; South Dakota, 34; Nebraska, 36; Kansas, 28 and Oklahoma and Texas 30. Of these species, those having the highest rating ecologically in the respective divisions appear in the following number: North Dakota, 23; South Dakota, 17; Nebraska, 11; Kansas, 11; and Oklahoma and Texas, 16. These data give emphasis to the fact, not usually recognized, that forest communities in the northern part of the shelterbelt area have fewer casual species and a greater number of important representative species than have those in the southern part of the area.

COMPOSITION OF TREE AND SHRUB COMMUNITIES

Despite wide variation from north to south in the climatic conditions of the shelterbelt zone, the native tree and shrub communities in the northern, central, and southern divisions of the region are surprisingly uniform in general appearance.

This uniformity would seem to be attributable to the fact that there is no wide variation from north to south in the balance between available soil water and loss of water by evaporation. The presence of one narrow plant-life form, the mixed prairie, throughout the entire region gives special emphasis to this uniformity of balance. That there is, however, a quite definite change in balance from east to west is evidenced by the difference in general appearance of tree and shrub communities within this short distance of approximately 100 miles. The most apparent change in such communities from north to south is change in species rather than in any important change in life form, whereas a lessening in abundance and vigor of growth in a number of species is noted as one crosses the zone westward. Figures 74 and 75 and figures 79 to 94 were not selected with this effect particularly in view, but they indicate the main aspects of tree and shrub development in the region. Figures 79, 80, 91, and 92 fairly well present conditions in its westward reaches.

|

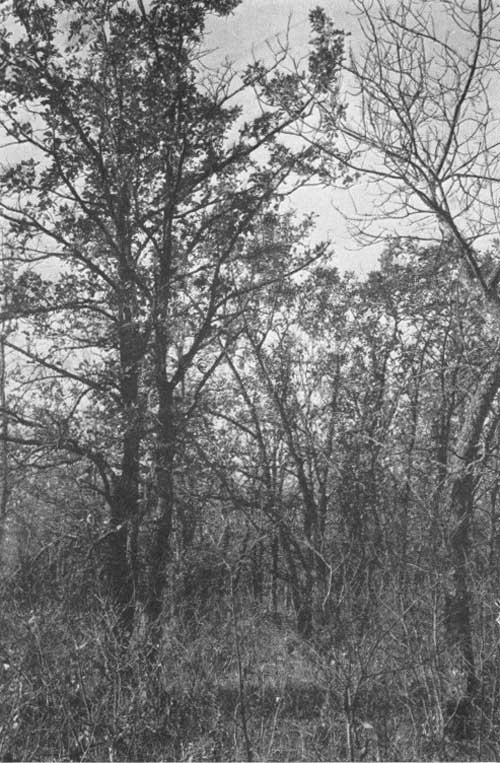

| FIGURE 79—Bur oak-prairie ash association on gentle slope on the south border of Devils Lake, N. Dak. The stand averages 300 trees per acre, 22 to 30 feet in height, and 3 to 8 inches in diameter breast high. The dominants of the dense undergrowth are choke cherry, serviceberry, and American plum. Other tall shrub associates are nannyberry, hawthorn, silverberry, and buffaloberry. Low shrubs growing in this cover and extending beyond the tall shrubs and trees are gooseberry, wild red raspberry, smooth sumac, western snowberry, and wild prairie rose. (F295443) |

|

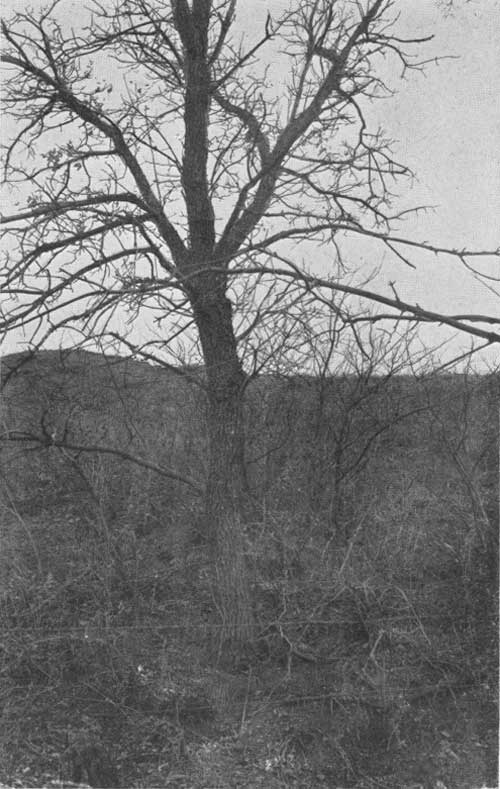

| FIGURE 80.—An isolated prairie ash, showing rough bark and generally stunted habit of growth under dry-land conditions. The slope borders a small intermittent stream 7 miles south of Mandan, N. Dak. (F295470) |

|

| FIGURE 81.—Association of prairie ash, American elm, Rocky Mountain red cedar, and boxelder on protected portions of the upper flood plain and on protected slopes bordering the Little Missouri River, 15 miles south of Watford city, N. Dak. These restricted communities contain 80 to 100 large trees per acre and 400 to 800 small trees, with ash predominating. A well-developed second story of wild plum, serviceberry, buffaloberry, dogwood, skunk brush, wild prairie rose, and creeping juniper also occurs. (F295445) |

The native forest communities within the shelterbelt area may be divided into two types: The hydrophytic type, immediately bordering water, as along permanent or intermittent streams or in pockets containing surplus water, and the upper flood-plain and upland type, farther removed from free water.

THE HYDROPHYTIC TYPE

Hydrophytic plant communities, occurring as noted above, more or less resemble the lower flood-plain communities of the eastern United States. They are more uniform as to species and general character throughout the area than are those of the other type. In all parts of the area, the borders of streams which have an abundance of water for at least a few months of the year are more or less completely lined with a mixture of sandbar willow, black willow, peachleaf willow, diamond willow, cottonwood, false-indigo, boxelder, and, in the South, buttonbush. On sandy borders of larger streams from southern Kansas southward, Tamarix gallica, an early escape, and the willow baccharis, a tall, alkali-tolerant shrub, are important members of the communities. To the westward, as permanent water supply becomes more of a rarity, the stand becomes more open, until at last, along a thousand small, intermittent tributaries, hydrophytic communities made up of widely spaced willow, cottonwood, and boxelder constitute the only forested areas.

There is little in this ultimate sparse and irregular grouping of trees to suggest typical forest conditions. Shade, quantity of duff, and protection afforded associate plants are at a minimum. Many of such groups are of recent origin, having developed only since the cessation of periodic prairie fires.

THE UPPER FLOOD-PLAIN AND UPLAND TYPE

Tree and shrub communities of the upland type are found on the upper flood plains of streams and on the bordering slopes. They may be of only occasional occurrence, as along the more shallow valleys, or may be continuous, as along deep valleys. Most of the valleys and slopes in the more easterly part of the shelterbelt zone afford sufficient protection for forest communities of this type.

The communities are made up of a few species of eastern upland and upper flood-plain trees which are adapted to growth in drier situations. With these species are associated a few species from the West. In composition and structure the communities vary, according to the protection of the site, percentage of available soil water, age, and stage of successional development, from sparse, poorly developed groups having 200 or fewer small trees per acre, with associated shrubs, to well-developed stands of as many as 900 mature trees per acre. In the latter case there is usually sufficient duff to form a rich soil, and only a sparse growth of the more tolerant shrubs. In less favorable sites or on grazed sites there may be no duff but an undercover of grass or, where grass is absent, a dense growth of less tolerant shrubs.

|

| FIGURE 82.—Comparison of prairie ash (right and left) and boxelder (center) under upland shelterbelt conditions. The ash is 15 feet high and 2 to 4 inches in diameter breast high. The boxelder has been cut back to live growth after severe drought injury. Northern Great Plains Field Station, Mandan, N. Dak. (F295465) |

|

| FIGURE 83.—Green ash-American elm association on the upper flood plain of Snake Creek, a tributary of the James River about 3 miles south of Ashton, S. Dak. A 1/10-acre plot contains 18 elm and 30 ash trees of a height of 30 to 40 feet and diameter breast high of 6 to 12 inches. (F295460) |

|

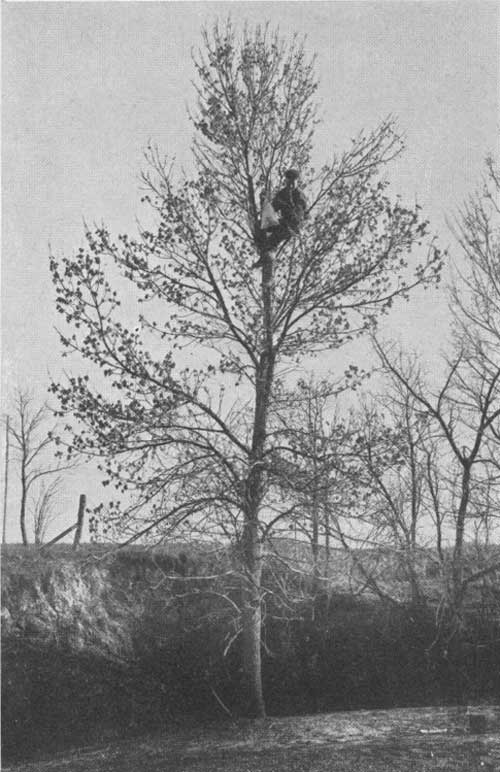

| FIGURE 84.—A specimen of green ash 25.5 feet in height and 0.3 inches in diameter breast high, growing in a sparse stand in the same general upland location shown in figure 89. The man is picking ash seeds. (F295458) |

This type differs so greatly in species for different parts of the area that it must be described as it occurs in the north, central, and south divisions of the zone. The chief difference evident in proceeding from the eastern border of the zone westward is a reduction in number of species and in size of trees and shrubs, and a less frequent occurrence of sites suitable for the development of the type. The change from north to south is a change in important species.

THE NORTHERN DIVISION

In North Dakota and the northern half of South Dakota, the important species of the upland type on the eastern border of the shelterbelt area are green ash, American elm, and bur oak. The three species grow well together, forming an association on upper flood plains and on protected slopes, where basswood is also of frequent occurrence. These communities take on a forestlike aspect, with plentiful shade, sufficient duff, and protection to associate plants. In the more favorable sites, 400 to 800 trees per acre, of diameter breast high averaging 8 inches and a height of 20 to 45 feet, may occur. Associate trees are the hackberry and slippery elm. Openings in the stand are often occupied by aspen and boxelder and, occasionally, by paper birch.

Species of small trees and shrubs within and bordering the stand are choke cherry, western choke cherry, wild plum, silverberry, buffaloberry, common prickly ash, serviceberry, golden currant, American black currant, Missouri gooseberry, and dwarf juniper. More xeric shrubs forming a zone between this type and the grassland are western snowberry, smooth sumac, wild prairie rose, and leadplant. Less favorable sites, as upland ravines and pockets, may contain most of these shrub species with no trees or with the young trees developing in the cover of shrubs. Especially in North Dakota, extensive areas on the more protected slopes are covered with western snowberry, some serviceberry, silverberry, buffaloberry, and choke cherry.

The most important change in type as we proceed westward is the dropping out of basswood, slippery elm, and common prickly-ash, the reduction in the size of the trees, and the increasing importance of shrubs in the sites, especially silverberry, buffaloberry, choke cherry, serviceberry, and western snowberry. Within the glaciated region in central North Dakota are a large number of potholes and poorly drained depressions, which are occupied by stands of aspen with some diamond and other willows.

One of the outstanding characteristics of this northern Dakota area is the persistence of prairie ash westward and towards the ends of ravines and in pockets. American elm is an accompanying species of slightly less importance in the stands.

|

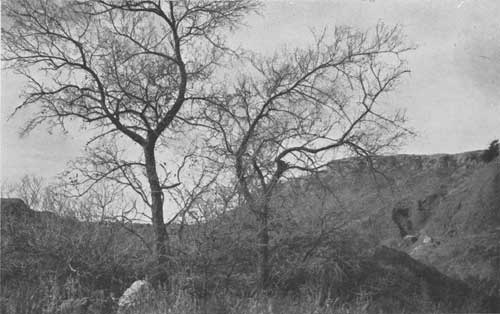

| FIGURE 85.—Prairie ash trees 15 to 18 feet in height and 4 to 5 inches in diameter breast high, growing in sparse stands on the upper flood plain of the Keyapaha River in southern South Dakota. (F295456) |

|

| FIGURE 86.—Mixed prairie on sandy loam, located 20 miles north of Wray, Colo., but typical of several sandy loam areas within the shelterbelt zone. Prairie grass dominants are prairie beardgrass, porcupine grass, side-oats grama, and three-awn. The chief short-grass dominant is blue grama, Bouteloua gracilis. Yucca is an indicator of deep-seated moisture. (F298268) |

|

| FIGURE 87.—A favorable site for shelterbelts within the zone. Dissected loess area in central Nebraska, 23 miles west of Albion. Western snowberry in protected pockets (in curve of road) and a well-developed shelterbelt in the background. (F298263) |

|

| FIGURE 88.—Forest community of above-average development near the eastern side of the shelterbelt zone along the Medicine Lodge River, 4.2 miles west of Medicine Lodge, Kans. The dominants on the upper flood plain and on the upland are American elm, green ash, black walnut, and paloblanco, and on the lower flood plain are cottonwood and boxelder. (F298271) |

|

| FIGURE 89.—A sparse stand of blackjack oak, with an occasional gum elastic tree, on sandy land bordering the North Canadian River on the eastern border of the shelterbelt area, near Seiling, Okla. F2105272 |

|

| FIGURE 90.—Marginal forest community of limited extent on the Cimarron River at New Liberty, Okla. The trees are paloblanco (hackberry) and the shrubs are skunk brush and sand plum. (F298272) |

THE CENTRAL DIVISION

The central division of the shelterbelt zone, lying in southern South Dakota and in Nebraska and extending to central Kansas, differs distinctly from the northern and southern divisions in composition of the tree and shrub communities of the upland type.

The center of distribution of trees in this division of the zone occurs in Nebraska, in the section around the sand hills and that bordering the Republican River and its tributaries. The important species of the upper flood plain and the upland are bur oak, American elm, and green ash (including prairie ash), the three species being of about equal abundance except toward the southern extreme of the area, where bur oak drops out. In forestlike aspect these communities are, in general, better developed than those in the westward reaches of the northern division. Associate trees, in most of the division, are hackberry, slippery elm, and eastern red cedar, with basswood, black walnut, honeylocust, coffeetree, and Rocky Mountain red cedar present, chiefly along the Niobrara and Republican Rivers. Occasional aspen and paper birch occur in openings only in South Dakota and northern Nebraska.

Species of small trees, and shrubs, seem to have at least as important a role in contact with the tree communities and on protected slopes and in depressions as in the northern division. Additional species of shrubs present in most of the area are roughleaf dogwood, American elder, and coralberry. Smooth sumac is much more important here in its invasion of the grassland, and serviceberry is less important. Of the entire division, the flatland of the second and third northern tiers of counties in Kansas seems to be the least favorable for the growth of trees and shrubs of this type.

Basswood, slippery elm, and common prickly-ash drop out toward the west, as in the northern division. Three shrubs—smooth sumac, roughleaf dogwood, and American elder—drop out westward, and serviceberry and common prickly-ash southwestward. Skunk brush is found in the western part of the division and not in the eastern, and coralberry replaces western snowberry in the undergrowth of sparse upland trees and in communities bordering trees and taller shrubs.

THE SOUTHERN DIVISION

The upper flood plain and upland vegetation of the southern division of the shelterbelt zone, from central Kansas to Lubbock, Tex., differs greatly in species from that of the other two divisions. For the entire eastern part of the division the two most important and generally distributed trees are the paloblanco and the American elm. The paloblanco species is Celtis reticulata Torr., with the variety C. reticulata vestita Sarg. more important in the northern and western parts of its range and persisting in less favorable sites elsewhere.

These species are the dominant trees on the upper flood plain, on well-developed upland sites, and in protected pockets and ravines in otherwise unfavorable situations, as those bordering the Cimarron and Canadian Rivers and their tributaries. Of the two, the elm dominates the more mature and extensive woodland communities, whereas the paloblanco (hackberry) dominates upland communities in the early stages of tree development, being often the only species present.

The western soapberry, a persistent, drought- and alkali-resistant tree, is often codominant with paloblanco in early stages of tree development on less-favorable sites. In the eastern half of the area it is of less importance, because there forest communities have reached a higher stage of development. In the western half of the area, because tree growth is chiefly confined to poorly developed groups in ravines, pockets, and other protected sites, the soapberry and the paloblanco may be considered the two most important trees. Of the two, soapberry appears to be the pioneer in sites which are definitely alkaline, and the paloblanco in less alkaline sites.

Associated with the dominants in most of the division, although usually rare in occurrence, are eastern red cedar, little walnut, bur oak, post oak, and blackjack oak. Honey mesquite is distributed over the region, chiefly in Texas, from the (southern) Canadian River southward. It forms a very sparse stand in the typical mixed prairie (associated with sagebrush) and also in some parts of the plains area. It is found with the soapberry and paloblanco along streams and in pockets.

The following trees are associated with the elm and paloblanco in the northeastern portion of the division: Green ash, black walnut, hackberry, and wild plum. None of them are abundant enough to be considered of even local dominance. Gum elastic, occurring in the central-eastern part, is a component of the woodland vegetation, although it usually appears as an occasional tree rather than in close stands. Its foliage, which persists until early winter, makes it conspicuous in the woodland cover in late summer and fall. The coffeetree and persimmon are only of local occurrence in the division.

The following small trees, shrubs, and vines are quite abundant within the elm-hackberry stands, and in places in the division they form dense borders for the trees; in many canyons and pockets they form thickets which are excellent seed beds for tree species; Sand plum, the small-lobed variety of post oak, two species of shin oak, choke cherry, golden currant, hop-tree, riverbank grape, Long's grape, coralberry, western skunk brush, smooth sumac, and wild rose. The sand plum and western skunk brush may be considered the dominants of these shrubby communities, the other species being either sparse over the entire range or of local occurrence.

In the entire division, oaks cover limited areas of sandy soils. Low sandy hills bordering streams in the eastern part are completely covered by blackjack oak for a distance of 1 to 4 or 5 miles back from the river. Post oak occurs in the slightly less sandy sites in these communities and forms small, sparse groups in favorable sites along the eastern border of the zone, as well as more and more isolated groups in pockets and ravines to the westward. Varieties of post oak, of which the small-lobed variety and Palmer's variety seem to be the most common, together with two definitely recognized species of shin oak, occur on sandy land in the area southwestward from Woodward, Okla.

|

| FIGURE 91.—Western soapberry on rough broken land bordering an intermittent stream west of the shelterbelt zone. 8 miles south of Borger, Tex. The trees are 10 to 25 feet high and 4 to 8 inches in diameter breast high. Most of the showy transparent yellow fruits remain on the tree during winter. (F298277) |

|

| FIGURE 92.—Occasional cottonwood trees, 25 to 40 feet in height and 12 to 36 incises in diameter breast high, and groups of paloblanco trees, 10 to 25 feet tall and 5 to 12 inches in diameter breast high, associated with western soapberry; 8 miles south of Borger, Tex. (F298278) |

ADAPTATION OF NATIVE TREES AND SHRUBS TO SHELTERBELT PLANTING

As we have now seen, the shelterbelt zone is, except for those areas more or less closely bordering streams and lakes, essentially a mixed prairie region, with portions of residual prairie distributed along most of its eastern border. Although growth conditions in the zone as a whole, originally covered with grasses, are more unfavorable than in its limited forested area, it is equally true that the progeny of tree and shrub species bordering streams or occupying the adjacent slopes and uplands are better adapted to planting in the area than are tree and shrub species grown under conditions widely removed and different from those of the planting sites. This principle is stated with particular reference to native American species, since the present discussion is not concerned with exotics. A few of the latter, from sites comparable to our shelterbelt area, have been successfully introduced; these and others deserve thorough test as to their adaptability and importance to major shelterbelt developments.

REACTION OF TREES AND SHRUBS TO DRY CONDITIONS; ECOTYPES

The trees and shrubs native to the area are more drought-resistant than representatives of the same species growing under more favorable moisture conditions, chiefly farther east. This is self-evident from their mere presence under more xeric conditions; it is also fully attested by morphological modifications generally recognized as of drought-resistant significance, which are present in these western forms.

According to the principle of Klebs, the course of plant development is determined by internal conditions, but these internal conditions may be significantly altered by external factors. When plant development has thus been, indirectly, altered by environment (ecological) conditions of sufficient effect to change the appearance of the plant, the new form may be recognized as an ecotype.

It seems to be well established by experimental evidence that changes that have occurred in the ecotype are not permanent, and that the plant or its progeny will revert to original form when replaced in the original environment. The important consideration is, however, that plants so modified have taken on structural differences and also a different physiological behavior.

Abundant water, sufficient nutrient materials from the soil, and carbon dioxide, oxygen, and light, as well as moderate temperature, are necessary for what is usually considered normal plant growth. Under typical forest conditions in the eastern part of the United States, none of these factors is lacking except light for certain of the understory plants, and the balance attained is, on the whole, favorable.

A reduction in water supply is the most important difference between the environment of the mixed prairie and the forested areas farther east. Lack of water has its effect on the first stage of growth (cell division) of the tree or shrub, but since only small quantities of water are required for this stage, the reduction in cell division is not great except in years of extreme drought.

It is in the second stage of growth that the water supply is most important, because abundant water, with attendant manufacture of small quantities of food (sugars) is required for the enlargement of the newly divided, plastic-walled cells at the tips of roots and stems and in the cambial region at which growth in girth appears. It is in this stage of growth, therefore, that lack of water in the soil shows important effects in the general stunting of trees and shrubs. Often a severe drought year will result in a great reduction in and even a total absence of this second stage of growth. The severity of the great drought of 1934 was not sufficient, however, to reduce cell enlargement to any unusual extent in the better adapted trees of the mixed-prairie region.

The maturing and differentiation of enlarged cells in the third period of growth is especially dependent upon the supply of sugars manufactured by the plant. Reduction of the water supply usually causes a shortening of the second period of growth in favor of the differentiation stage, as does also an increase in temperature. This is the reaction which usually causes the stunting effect noticed above. Under very severe drought conditions there may be insufficient moisture for production of the sugars required for complete differentiation, but the usual reaction is the hastening of differentiation, especially of the flowers and fruits, and a consequent reduction in growth of the other parts of the plant.

Under the average precipitation conditions of the shelterbelt area, even the favorable soils have insufficient moisture for optimum growth of trees, but sufficient moisture for their continued growth and fruiting; in other words, the food-making process of the tree is not reduced below the minimum necessary to its life. Sugars which, under more favorable moisture conditions, would be used in growth accumulate and serve as the stimulus and the materials for differentiation. Cuticle and cork show more pronounced development, cell walls are thickened, fibers and conducting elements are more abundant in the new tissues; resins, gums, and the like accumulate, the cells become more resistant to drying and cold, and flowering and fruiting occur more regularly. Under these conditions of differentiation, induced by a moderate or average shortage of water, organic materials which normally accumulate in the aboveground parts and, with a sufficient water supply, promote top growth, move to the roots and stimulate root development. This increase in the ratio of roots to aboveground parts, which is characteristic of dry-land trees and shrubs, insures water absorption from larger soil areas and consequently a greater chance of permanent establishment.

|

| FIGURE 93.—Shin oaks invading sparse tall-grass prairie on sandy soil, 8 miles west of Wellington, Tex. |

|

| FIGURE 94.—Gravelly floor of Palo Duro Canyon, beyond the western border of the shelterbelt zone, 14 miles east of Canyon, Tex. The chief woody plants are honey mesquite, redberry juniper, eastern red cedar, paloblanco, and lemonade sumac, growing with species of cactus and short grasses. (F28928) |

CHARACTERISTICS OF TREES GROWING UNDER XERIC CONDITIONS

Because of their apparent adaptability to environmental conditions in some such manner as above described, native green ash trees were given particular study in the 1934 field survey. Ash "stations", at which special investigations and collections were made, were located throughout the northern and central zone area.

Comparison of the eastern with the western forms is complicated by the recognition of the prairie ash by some authorities as a separate species, Fraxinus campestris Britt. and by others a variety, or simply an ecotype. Additional study is necessary before even an approximately satisfactory classification of the western green ashes can be made in this respect, and a careful investigation of the variation in structural and physiological response of the ash trees of the region is now in progress under the author's direction. Through study of twig characters (pubescence, leaf scars, bundle scars, and buds) and of leaf and fruit characters, an attempt is being made to separate the group into different forms on a morphological basis. A physiological study of the seedlings and of the parent trees is also being made to determine the possibility of making a division on the basis of physiological behavior. If these two attempts are successful, it may be found possible to separate the group into one or more ecotypes, and to select by morphological criteria those best adapted physiologically to survive.

The most apparent silvical variation of the green and prairie ashes, including both Fraxinus pennsylvanica lanceolata (Borkh.) Sarg. and F. campestris, from observations at selected stations in order from east to west is reduction in size, as demonstrated by the following average measurements of mature trees:

| Height of tree (feet) |

Diameter, breast high (inches) | |

| Emmetsburg (northern Iowa) | 57 | 17.9 |

| Grand Forks, N. Dak | 44 | 11.7 |

| Devils Lake, N. Dak | 25 | 5.2 |

| Williston, N. Dak | 20.5 | 1.9 |

In general, an ecotype or special form of an eastern tree which has become established in or beyond the shelterbelt area shows several characteristic differences from its original in addition to those of size. These results, verified by observation and data from several sources, would seem to arise from the series of reactions of the tree to dry conditions Which have been previously discussed. They may be summarized as follows:

Increase in:

Crown spread—Slight.

Ratio of girth to height.

Ratio of twig diameter to length.

Thickness of bark.

Pubescence of twigs and leaves.

Thickness of leaves (with thickening of cuticle).

Production of resins, gums, alkaloids.

Thickness of woody and fibrous elements.

Regularity of flowering and fruiting.

Ratio of root growth to crown growth.

Fibrous development of root system.

Extent of root system.

Reduction in:

Height.

Girth.

Rate of growth.

Length of nodes.

In amount of food made, but not in rate.

Again referring to the green ash of the shelterbelt zone, modifications closely paralleling the above and thoroughly integrated into an adapted form whose habitat requirements accord more closely with those of the prairie grasses than do those of eastern ash are recognized in it. A typical prairie ash tree of the kind in question is shown in figure 80. In general, this western form of the green ash is a more compact and drought-resistant tree than its eastern congener. The particular tree shown has a height of about 20 feet a crown round in outline rather than elongate, a rough appearance resembling the bur oak, shortened internodes, pubescent twigs, and shorter, thicker, more compact leaves. The girth is much reduced as compared to that of the eastern form, but the ratio of girth to height is increased.

The physiological activities of the tree have also become modified toward true drought resistance in the increased rate of food making when water relations are favorable and in the adaptability to quick change in response to lack of water during dry seasons.

Mass selection for drought-resistance has probably operated in a manner somewhat as follows: A tree, as the ash or elm or bur oak, which became established in a ravine at the edge of the shelterbelt area in a given year, bore a few hundred or a few thousand fruits. Of this number a small percentage fell, were blown, or were carried by birds or rodents into favorable situations, where the seed germinated. Severe conditions of various kinds accounted for the death of most of the seedlings, but the inheritance of various unit characters for survival, such as vigor, effective root system, thick bark, and the like, contributed to the establishment of a few of them and to the successful development of a still smaller number.

Those that developed had, in a higher degree than the others, the characteristics necessary for germination and establishment in an unfavorable habitat. A higher percentage of progeny of this generation would have those characteristics necessary for survival than progeny of the original parent tree had. Repetition of this process of mass selection through many generations would reasonably account for the development in the region of large numbers of trees representing ecotypes of eastern species.

THE ADAPTATION OF TREES AND SHRUBS TO ALKALI

According to Marbut, there is present in the entire shelterbelt area, on some horizon of the soil section, a zone of alkaline salt accumulation, chiefly calcium carbonate. The zone of accumulation, because of the decreased depth of water penetration, is nearer the surface as one proceeds westward. The presence of such a zone would indicate that all trees and shrubs of the area are to some extent alkali-resistant as compared to forms of the same species growing in the east, and the closeness with which the roots of a given plant can approach the zone of carbonate accumulation may be taken as a rough measure of that resistance.

The series of reactions of such plants to a gradual increase in alkalinity or salinity of the soil solution is to some extent comparable to the reactions to dry conditions, but the alkali response is more complex because of the great variety of the chemical reactions involved. The response also differs according to the quantity of each compound in the soil solution; very weak solutions of many alkalis increase the rate of water absorption. whereas the presence of any considerable quantity of alkali salts in the soil solution results in a decrease in the rate of water absorption and in the injury and inhibited development of root hairs and roots of the plant. In the case of neutral salts, the rate of absorption may be decreased only because of the lowered diffusion-gradient of water into the plant as concentration of the soil solution increases.

The degree of modification of trees and shrubs of the area toward alkali resistance is an important factor in their adaptability to shelterbelt conditions. The more definite adaptation of several species, as the willow baccharis, western soapberry, and honey mesquite, in this respect makes possible their planting and growth in moderately alkaline areas. Thereafter, by stages of plant succession, the alkaline sites may be slowly modified and made more favorable with deeper penetration of roots and resultant leaching of alkali salts.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

shelterbelt/sec13.htm Last Updated: 08-Jul-2011 |