| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

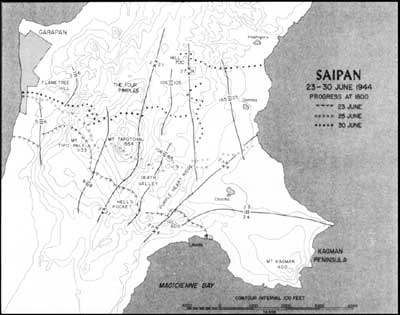

BREACHING THE MARIANAS: The Battle for Saipan by Captain John C. Chapin U.S. Marine Corps Reserve (Ret) D+8—D+15, 23-30 June Complications of a serious nature arose in the execution of the battle plan for 23 June. The battalion of the 105th Infantry still had not cleaned out Nafutan Point; there were semantic and communications differences between the two Smith generals as to orders about who would do what and when; the 106th and 165th Infantry got all tangled up in themselves during a march to take over the center portion of the American lines and were too late to jump off in the attack, thus delaying the attacks of the Marines. When the Army regiments did move out, they found that the rugged terrain in their sector and the determined enemy in camouflaged weapons positions in caves of the steep slope leading up to Mount Tapotchau made forward progress slow and difficult. The 27th Infantry Division was stalled. The corps commander, Holland Smith, was very displeased with this situation. It had started with the difficulties experienced in getting that division ashore; it was exacerbated by the time it was taking to secure Nafutan Point and the mix-up in orders there; now the advancing Marine divisions were getting infiltration and enfilading fire on their flanks because of the 27th's lack of progress. Accordingly, Lieutenant General Holland Smith met that afternoon with Major General Sanderford Jarman, USA, who was slated to be the island garrison commander, and asked him to press Major General Ralph Smith for much more aggressive action by the 27th. Jarman later stated:

This blunt meeting was followed the next morning (D+9) by an even blunter message from Holland Smith to Ralph Smith:

These objectives were given dramatic names by the Army regiments: Hell's Pocket, Death Valley, and Purple Heart Ridge. It was certainly true that the terrain was perfect for the dug-in Japanese defenders: visibility from the slopes of Mount Tapotchau and from the ridge gave them fields of fire to rake any attack up the valley. Holland Smith didn't fully recognize the severity of the opposition, and, by the end of the day, the 106th Infantry had gained little, while the 165th Infantry had been "thrown back onto the original line of departure." Meanwhile, the 2d Marine Division on the left was painfully slugging its way forward in the tortuous environs around Mount Tapotchau. The 4th Marine Division (on the right) pivoted east, driving fast into the Kagman Peninsula. There the ground was level, a plus, but covered with cane fields, a big minus, as the rifle companies well knew.

A platoon leader remarked:

Along with the death toll in the cane fields came the physical demands placed on the troops by the hot tropical climate. Lieutenant Chapin noted small, human issues that loomed large in the minds of the assault troops:

While these local events transpired on the front lines, a major upheaval was taking place in the rear. Seeing that the corps line would be bent back some 1,500 yards in the zone of the 27th Infantry Division, Holland Smith had had enough. He went to see Admirals Spruance and Turner to obtain permission to relieve Ralph Smith of command of his division.

After reviewing the Marine general's deeply felt criticism of the 27th Infantry Division's "defective performance," the admirals agreed to the requested change, and Ralph Smith was superseded by Major General Jarman on 24 June. A furor arose, with bitter inter service recriminations, and the flames were fanned by lurid press reports. Holland Smith summarized his feelings three days after the relief. According to a unit his tory, The 27th Infantry Division in World War II, he stated, "The 27th Division won't fight, and Ralph Smith will not make them fight." Army generals were furious, and in Hawaii, Lieutenant General Robert Richardson, commander of the U.S. Army in the Pacific (USARPAC) convened an Army board of inquiry over the matter. The issue reached to the highest military levels in Washington. While the Army's Deputy Chief of Staff, Lieutenant General Joseph T. McNarney, reviewed the matter, he found some faults with Holland Smith, but then went on to say that Ralph Smith failed to exact the performance expected from a well-trained division, as evidenced by poor leadership on the part of some regimental and battalion commanders, undue hesitancy to bypass snipers "with a tendency to alibi because of lack of reserves to mop up," poor march discipline, and lack of reconnaissance. The Army's official summary, United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific, Campaign in the Marianas (published 15 years after the operations) attributed some errors to Holland Smith's handling of a real problem, and it also gave full recognition to the difficult terrain and bitter resistance that the Army regiments faced. The history stated that:

Back where the conflict was with the Japanese, the 4th Marine Division had overrun most of the Kagman Peninsula by the night of D+10. The shoreline cliffs provoked sobering thoughts in a young officer in the 24th Marines:

This unfinished state of the Japanese defenses was, in fact, a critical factor in the final American victory on Saipan. The blockading success of far-ranging submarines of the U.S. Navy had drastically reduced the supplies of cement and other construction materials destined for elaborate Saipan defenses, as well as the number of troop ships carrying Japanese reinforcements to the island. Then the quick success of the Marshalls campaign had speeded up the Marianas thrust by three months. This was decisive, for "one prisoner of war later said that, had the American assault come three months later, the island would have been impregnable." The 4th Marine Division encountered more than cane fields in the Kagman Peninsula—the cliffs near the ocean were studded with caves. A 20-year-old private first class in Company E, 2d Battalion, 23d Marines, Robert F. Graf, described the Marine system for dealing with these and the others that were found all through the bitter campaign:

Graf went on to picture the use of flame-throwing tanks, the ultimate weapon for dealing with the enemy deep in his hideouts. He continued:

A fellow rifleman from Graf's company told him this story:

These attacks on caves were a tricky business, because of orders not to kill any civilians who were also inside many of them, hiding from the fighting. Graf recounted his experiences further:

As the sick, scared, and often starving civilians would emerge from their hideouts, there were many pitiful scenes:

One of the captured persons impressed Graf so very much that the memory was vivid many years later. A Japanese woman, obviously an aristocrat, probably a wife or mistress of a high-ranking officer, "was captured. She was dressed in traditional Japanese clothing: a brilliant kimono, a broad sash around the waist, hair combed, lacquered and spotlessly clean. Although," as Graf remarked, "she knew not what her fate would be in the hands of us, the barbarians, she stood there straight, proud, and seemingly unafraid. To me, she seemed like a queen." Over on the west side of Saipan, the 2d Marine Division had a memorable day on 25 June. Ever since the landing, the towering peak of Mount Tapotchau had swarmed with Japanese artillery spotters looking straight down on every Marine move and then calling in precisely accurate fire on the American troops. Now, however, in a series of brilliant tactical maneuvers, with a battalion of the 8th Marines clawing up the eastern slope, a battalion of the 29th Marines (then attached to the 8th Marines) was able to infiltrate around the right flank in single file behind a screen of smoke and gain the dominating peak without the loss of a single man. Meanwhile, back at Nafutan Point, the battalion of the 105th Infantry assigned to clean out the by passed Japanese pockets had had continuous problems. The official Army account commented, "The attack of the infantry companies was frequently uncoordinated; units repeatedly withdrew from advanced positions to their previous night's bivouacs; they repeatedly yielded ground they had gained." The stalemate came to a climax on the night of D+11. Approximately 500 of the trapped Japanese, all the able-bodied men who remained, passed "undetected" or "sneaked through" (as the Army later reported) the lines of the encircling battalion. The enemy headed for nearby Aslito airfield and there was chaos initially there. One P-47 plane was destroyed and two others damaged. The Japanese quickly continued on to Hill 500, hoping to reunite there with their main forces. What they found instead was the 25th Marines resting in reserve with an artillery battalion of the 14th Marines. The escaping Japanese were finished off the following morning.

On the front lines in the center of the island, General Jarman, now in temporary command of the 27th Infantry Division, took direct action that same day (D+11). An inspection by two of his senior officers of the near edge of Death Valley revealed that battalions of the 105th Infantry were standing still when there was no reason why they should not move forward." That did it. Jarman relieved the colonel commanding the 106th and replaced him with his division chief of staff. (Nineteen other officers of the 27th Infantry Division were also relieved after the Saipan battle was over, although only one of them had commanded a unit in battle.) While these developments were taking place in the upper echelons, the junior officers in the front lines had their own, more immediate, daily concerns. As the author recalled:

For the next several days, the 27th Infantry Division probed and maneuvered and attacked at Hell's Pocket, Death Valley, and Purple Heart Ridge. On 28 June, Army Major General George W. Griner, who had been quickly sent from Hawaii upon the relief of Ralph Smith, took over command of the division, so Jarman could revert to his previous assignment as garrison force commander. The 106th marked the day by eradicating the last enemy resistance in the spot that had caused so much grief: Hell's Pocket. The 2d Marine Division mean while inched northward toward the town of Garapan, meeting ferocious enemy resistance. Tipo Pali was now in 6th Marines' hands. The 8th Marines encountered four small hills strongly defended by the enemy. Because of their size in comparison with Mount Tapotchau, they were called "pimples." Each was named after a battalion commander. Painfully, one by one, they were assaulted and taken over the next few days.

Near Garapan, about 500 yards to the front of the 2d Marines' lines, an enemy platoon on what was named "Flame Tree Hill" was well dug in, utilizing the caves masked by the bright foliage on the hill. The morning of 29 June, a heavy artillery barrage as well as machine gun and mortar fire raked the slopes of the hill. Then friendly mortars laid a smoke screen. This was followed by a pause in all firing. As hoped, the enemy raced from their caves to repel the expected attack. Suddenly the mortars lobbed high explosives on the hill. Artillery shells equipped with time fuses and machine gun and rifle fire laid down another heavy barrage. The enemy, caught in the open, was wiped out almost to a man. To the right, the 6th Marines mopped up its area and now held the most commanding ground, with all three of its battalions in favorable positions. In fact, since replacement drafts had not yet arrived, the 2d Marine Division had all three of its infantry regiments deployed on line. Thus it was necessary for its commander, Major General Watson, to organize a division reserve from support units. The pressure on manpower was further illustrated by the fact that, in this difficult terrain, "eight stretcher bearers were needed to evacuate one wounded Marine." In addition, there was, of course, the deep-seated psychological and physical pressure from the constant, day after day, close combat. "Every one on the island felt the weight of fatigue settling down."

On the 4th Division front, the drive forward was easier, but its left flank had to be bent sharply back ward toward the 27th Infantry Division. By nightfall on 28 June, the Marine division's lines formed an inverted L with the 23d Marines and part of the 165th Infantry facing north, while the rest of the Army regiment and two battalions of the 24th Marines faced west. This strange alignment was a focus of attention when each battalion was issued its nightly overlay from corps headquarters showing the lines of the corps at that time, so that friendly fire from artillery and supporting Navy destroyers would not hit friendly troops. Once again, enemy planes raided, hitting both the airfield and anchorage. As usual, enemy night patrols were active. The end of the saga of Nafutan Point, way to the rear, had come the day before (27 June). The Japanese breakout had left almost no fighting men behind there. Accordingly, the battalion of the 105th Infantry at last overran the area after enduring a final banzai charge. The soldiers found over 500 enemy bodies in the area, some killed in the charge and some by their own hand. D+15 (30 June) marked a good day for the Army. After fierce fighting, the 27th Infantry Division finally burst through Death Valley, captured Purple Heart Ridge, and drew alongside the 8th Marines. Holland Smith gave due recognition: "No one had any tougher job to do." The gaps on the flanks with the 2d and 4th Marine Divisions were now closed. In doing so, the Army had sustained most of the 1,836 casualties inflicted upon it since D-Day. The 4th Marine Division, however, had suffered 4,454 casualties to date, while the 2d Marine Division had lost 4,488 men. The corps front now ran from Garapan, past the four pimples, to the 4th Marine Division's left boundary. Here, it ran sharply northward to Hill 700. From there it ran to the east coast. Central Saipan was in American hands. Most of the replenishment supplies had been unloaded. The enemy had begun withdrawing to his preplanned final defensive lines. The Army's official history summed up these days costly victories this way "The battle for central Saipan can be said to have come to a successful end."

|