|

BREACHING THE MARIANAS: The Battle for Saipan

by Captain John C. Chapin

U.S. Marine Corps Reserve (Ret)

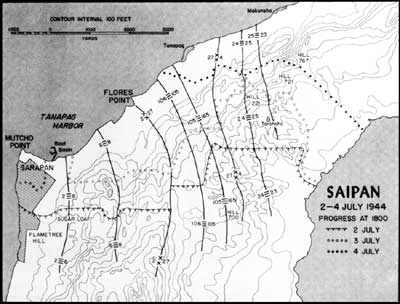

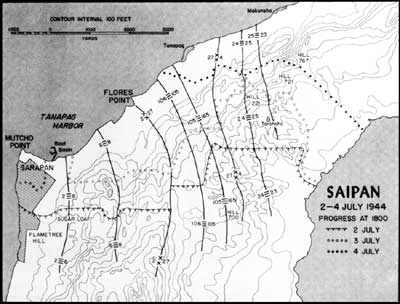

D+16—D+19, 1—4 July

Now Holland Smith turned his attention to operation

plans to drive through the northern third of Saipan and bring the

campaign to a successful, albeit a bloody, conclusion. His next

objective line ran from Garapan up the west coast to Tanapag and then

eastward across the island. Past Tanapag, near Flores Point, the 2d

Marine Division would be pinched out and become the corps reserve. That

would leave the 27th Infantry Division and the 4th Marine Division to

assault General Saito's final defenses.

The easiest assignment during this period fell to the

4th Marine Division on the east coast. It advanced 3,500 yards against

light opposition, veering to its left, ending on 4 July with its left

flank some 2,000 yards north of Tanapag, right on the west coast.

|

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

As usual, what looked like "light opposition" to

General Schmidt in his divisional CP looked very different to that

tired, tense lieutenant who described a painfully typical rifle platoon

situation on D+16:

I took the rest of my men and we proceeded—very

cautiously—to comb the area. It was a terrible place: the rocks and

creepers were so interwoven that they formed an almost impenetrable

barrier; visibility was limited to a few feet. After what had happened

to [my wounded sergeant], the atmosphere of the place was very tense. We

located some rock crevices we thought the Japs might be in, and I tried

calling to them in our Japanese combat phrases to come out and

surrender. This proved fruitless, and it let the Japs know exactly where

we were, while we had no idea of their location. Then I tried to

maneuver our flamethrower man into a position where he could give the

crevice a blast without becoming a sitting-duck target himself. Because

of the configuration of the ground, this proved impossible.

Right about now, there was a shot off to our left. We

started over to investigate and all hell broke loose! A Jap automatic

weapon opened up right beside us. We all hit the deck automatically. No

one was hit (for a change), but we couldn't spot the exact location of

the weapon (as usual). I called to the man who'd been over on the left

flank. No answer. What had happened to him?

|

|

The only way to deal with some Japanese in their

well-protected defenses was to blast them with a flame-thrower.

Department of

Defense Photo (USMC) 84885

|

At this point more enemy fire spattered around the

small group of Marines. The source seemed to be right on top of them, so

the lieutenant told two of his men to throw some grenades over into the

area he thought the fire was coming from—about 20 feet away. Under

cover of that, the Marines worked a rifleman forward a couple of yards

to try to get a bead on the Japanese, but he was unable to spot them and

the enemy fire seemed to grow heavier.

Now the lieutenant began to get very worried:

Here we were—completely isolated from the rest

of the company—only half a dozen of us left—our flank man had

disappeared and now we were getting heavy fire from an uncertain number

of Japs who were right in our middle and whom we couldn't locate! Some

of the men were getting a little jittery I could see, so I tried to

appear as calm and cool as I could (although I didn't feel that way

inside!). I decided to move back to the other end of the hilltop and

report to [our company commander] on the phone. If I could get his OK, I

would then contact [another one of our platoons] for reinforcements, and

we could move back into this area and clean out the Jap pocket.

Pressing hard against the Japanese defenses

constantly resulted in these kinds of face-to face encounters. Three

days later (D+19), Lieutenant Colonel Chambers observed a memorable act

of bravery:

Three of our tanks came along the road. . . . They

made the turn to the south and then took the wrong turn, which took them

off the high ground and into a cave area where there were literally

hundreds of Japs, who swarmed all over the tanks. We were watching and

heard on the radio that (the lieutenant) who commanded the tanks was

hollering for help, and I don't blame him. They had formed a triangle

and covered each other with the co-axial guns as best as they could.

|

|

He

may have started out sitting on a dud 16-inch Navy shell, enjoying a

smoke while emptying sand from his "boon dockers," but by the end of the

campaign, three weeks later, he had had too little sleep, too many fire

fights, and too many buddies dead. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

85221

|

The commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, 25th

Marines, Lieutenant Colonel Hollis U. ("Musty") Mustain was nearest the

crisis. Chambers went on:

Mustain's executive officer was a regular major by

the name of Fenton Mee. Musty and I were together, and when radio

operators told us what was going on, Musty turned to Mee and said, "Get

some people there and get those tanks out."

Mee turned around to his battalion CP, who were all

staff people. He just pointed and said, "Let's get going." He turned and

took off. I can still see his face—he figured he was going to get

killed. They got there and the Japs pulled out. This let the tanks get

out, and they were saved. It was one of the bravest things I ever saw

people do.

Chambers also noted that, by D+19, out of 28 officers

and 690 enlisted men in his rifle companies at the start of the

campaign, he now had only 6 officers and 315 men left in those

companies. Counting his headquarters company, he had just 468 men

remaining of the battalion's original total strength of 1,050, so one

rifle company simply had to be disbanded. The grim toll was repeated in

another battalion which had had 22 out of 29 officers and 490 enlisted

men either killed or wounded in action.

Next to the 4th Marine Division was the 27th Infantry

Division in the center of the line of attack. It, too, had a far easier

time than in the grinding experiences it had just come through. Its

advance also veered left, and was "against negligible resistance" with

"the enemy in full flight." Thus it reached the west coast, pinching off

the 2d Marine Division and allowing it to go into reserve.

There was a different story in the 2d Marine Division

zone of action at the beginning of this period. On 2 July Flametree Hill

was seized and the 2d Marines stormed into Garapan, the second largest

city in the Mariana Islands. What the regiment found was a shambles; the

town had been completely leveled by naval gunfire and Marine

artillery.

|

|

"Patrol, Saipan" By Richard Gilney. Marine Corps Art

Collection

|

The official Marine history pictures the scene:

Twisted metal roof tops now littered the area,

shielding Japanese snipers. A number of deftly hidden pillboxes were

scattered among the ruins. Assault engineers, covered by riflemen,

slipped behind such obstacles to set explosives while flamethrowers

seared the front. Assisted by the engineers, and supported by tanks and

75mm self-propelled guns of the regimental weapons company, the 2d

Marines beat down the scattered resistance before nightfall. On the

beaches, suppressing fire from the LVT(A)s of the 2d Armored Amphibian

Battalion silenced the Japanese weapons located near the water.

Moving past the town, the 2d Marine Division drove

towards Flores Point, halfway to Tanapag. Along the way, with filthy

uniforms, stiff with sweat and dirt after over two weeks of fierce

fighting, the Marines joyfully dipped their heads and hands into the

cool ocean waters.

With the other two divisions already having veered

their attack to the left and reached the northwest coast, the 2d Marine

Division was now able to go into corps reserve, as planned, on 4 July.

(Holland Smith, seeing the end in sight on Saipan, wanted this division

rested for the forthcoming assault on neighboring Tinian Island.)

The Japanese, meanwhile, were falling back to a final

defensive line north of Garapan. The American attack of the preceding

weeks had not only shattered their manpower, their artillery, and their

tanks, but the enemy also was desperate for food. "Many of them had been

so pressed for provisions that they were eating field grass and tree

bark."

|