| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

THE RIGHT TO FIGHT: African-American Marines in World War II by Bernard C. Nalty Building the 51st Defense Battalion The proliferation of African American units and the expansion of activity at Montford Point interfered with the organization and training of the 51st Defense Battalion (Composite) by making demands on the pool of black noncommissioned officers that Woods, Holdahl, and the shrinking Special Enlisted Staff had assembled. The first, and for a time the only, Marine Corps combat unit to be manned by blacks found itself in competition with another defense battalion, the new combat support outfits (depot and ammunition companies), the Stewards' Branch, and, as before, the recruit training function. So thinly spread was the African-American enlisted leadership that the same individuals might serve in a succession of units. "Hashmark" Johnson, a DI in boot camp, ended up with the 52d Defense Battalion. Similarly, Edgar Huff, also a DI, moved on to other assignments, including first sergeant of one of the combat service support companies. The 51st had attained only half its authorized strength on 21 April, when a new commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Floyd A. Stephenson, took over from Lieutenant Colonel Onley. Stephenson, in command of a defense battalion at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked, later declared that he "had no brief for the Negro program in the Marine Corps," since he hailed from Texas, "where matters relating to Negroes are normally given the closest critical scrutiny," a euphemistic description of Jim Crow. He was, in short, the product of a segregated society, but despite his background, he tackled his new assignment with enthusiasm and skill. African Americans, he soon discovered, could learn to perform all the duties required in a defense battalion. By the end of 1942, the nature of the defense battalion had begun changing. Already the Marine Corps had stricken light tanks from the table of organization and equipment, and, as close combat became increasingly less likely, the rifle company and the pack howitzers followed the armor into oblivion. Emphasis shifted from repulsing amphibious landings to defending against Japanese air strikes and hit-and-run raids by warships. In June 1943, the qualifier "Composite" disappeared from the designation of the 51st Defense Battalion, the 155mm battery became a group, and the machine gun unit evolved into the Special Weapons Group, with 20mm and 40mm weapons, as well as machine guns. A month later, the 155mm Group be came the Seacoast Artillery Group, and the 90mm outfit, with its search lights, the Antiaircraft Artillery Group. No further changes took place before the battalion went overseas.

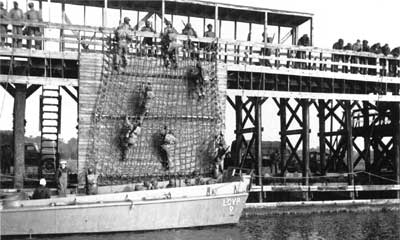

As this evolution in organization and weaponry began, Stephenson set to work building a segregated battalion with the African-American Marines available to him. They had undergone classification testing at Montford Point and been grouped according to their scores. Normally men in Category IV would at best attain the rank of corporal, whereas those in Categories III through I generally had the aptitude for higher rank, though no black could aspire to officer training. Since classification scores tended to be fallible, Stephenson and his officers had to rely on instruction, observation, and evaluation as they tried to create a cadre of black noncommissioned officers in nine months or less. Each group within the battalion — at the time 155mm artillery, 90mm antiaircraft artillery, and special weapons — maintained standing examination boards, which included the group commander. The officers and noncommissioned officers recommended candidates for promotion, who then appeared before the group's examining board. The first test in this series, for promotion to private first class, was a written examination usually administered during or shortly after boot camp, but the others, given during unit training, consisted of 25 to 30 questions answered orally. The names of those who survived the screening went to the battalion commander who matched candidates with openings. "Many qualified men waited from month to month," Stephenson recalled, although in six or eight instances over perhaps nine months "an especially meritorious, mature man was advanced two grades on successive days to place especially talented leaders in positions of responsibility." Just as "Hashmark" Johnson and Edgar Huff had advanced rapidly within the recruit training operation, Obie Hall became a platoon sergeant within six months of joining the battalion. The tempo of training picked up throughout the summer and fall of 1943, as African-American noncommissioned officers replaced more of the white enlisted men who had taught them to handle weapons and lead men in combat. On 20 August, the 51st Defense Battalion suffered its first fatality. During a disembarkation exercise, while the Marines of the 155mm Artillery Group scrambled down a net draped over a wooden structure representing the side of a transport, Corporal Gilbert Fraser, Jr., slipped, fell into a landing craft in the water below, and suffered injuries that claimed his life. In memory of the 30-year-old graduate of Virginia Union College, the road leading from Montford Point Camp to the artillery range became Fraser Road.

Although the men of the 51st Defense Battalion had to assume the responsibilities of squad leaders and platoon sergeants even as they learned to care for and fire the battalion's weapons, the black Marines met this challenge, as they demonstrated in November 1943. During firing exercises — while Secretary of the Navy Knox, General Holcomb, and Colonel Johnson of the Selective Service System watched — an African-American crew opened fire with a 90mm gun at a sleeve target being towed overhead and hit it within just 60 seconds. Lieutenant Colonel Stephenson, listening for the Commandant's reaction, heard him say "I think they're ready now." Few other crews in the 51st could match this performance, and a number of them clearly needed further training, as some of their officers warned at the time. The four days of firing at the end of November could not be repeated, however, for the unit would depart sooner than originally planned on the first leg of a journey to the Pacific.

Where in the Pacific area would that journey end? Marine Major General Charles F. B. Price, in command of American forces in Samoa, had already warned against sending the African-Americans there. He based his opinion on his interpretation of the science of genetics. The light-skinned Polynesians, whom he considered "primitively romantic" by nature, had mingled freely with whites to produce "a very high class half caste," and liaisons with Chinese had resulted in "a very desirable type" of offspring. The arrival of a battalion of black Marines, however, would "infuse enough Negro blood into the population to make the island predominately Negro" and produce what Price considered "a very undesirable citizen." Better, the general suggested, to send the 51st Defense Battalion to a region populated by Melanesians, where the "higher type of intelligence" among the African-Americans would not only "cause no racial strain" but also "actually raise the level of physical and mental standards" among the black islanders. After the general forwarded his recommendation to Marine Corps headquarters, though not necessarily because of his reasoning, two black depot companies that arrived in Samoa during October 1943 were promptly sent elsewhere. Whatever its ultimate destination, the 51st Defense Battalion started off to war early in January 1944, and by the 19th, most of the unit — less 400 men transferred to the newly organized 52d Defense Battalion — and the bulk of its gear were moving by rail toward San Diego. On that day, while Stephenson supervised the loading of the last of the 175 freight cars assigned to move the unit's equipment, a few of the black Marines waiting to board a troop train began celebrating their imminent departure by downing a few beers too many at the Montford Point snack bar, which lived up to the nickname of "slop chute," universally applied to such facilities. The military police, all of them white, cut off the supply of beer by closing the place and forcing the blacks to leave. Once outside, the men of the battalion milled about and began throwing rocks and shattering the windows of the snack bar. Again the military police intervened, one of them firing shots into the air to disperse the unruly crowd. Some of the black Marines fled into the nearby theater, which the military police promptly shut down. At this point, someone fired 15 or 20 shots into the air from the vicinity of a footbridge linking the Montford Point Camp with Camp Knox, the old CCC facility, where those members of the 51st still in the area had their quarters. A stray bullet wounded a drill instructor, Corporal Rolland W. Curtiss, who was leading his platoon on a night march. Despite the injury and a momentary panic among his recruits, the corporal brought his men safely back to their barracks.

Although one rifle assigned to the battalion showed signs of firing and another appeared to have been cleaned with hair oil, perhaps to disguise recent use, neither could be linked to a specific Marine. Records proved to be in disarray, with serial numbers copied incorrectly and individuals in possession of weapons other than the ones they were supposed to have. The breakdown of accountability impeded a hurried investigation by Stephenson and four of his officers and prevented them from determining who had fired the shots. The mix-up in weapons resulted from the confusion of the move and the inexperience of recently promoted junior noncommissioned officers, who failed to ride herd on their men. Colonel Woods witnessed the results of this failure when he inspected the vacated quarters and found "a filthy and unsanitary area." Indeed, one of the noncoms later admitted to simply assuming that "someone is going to pick it up," much as parents would make sure that nothing of value remained behind when a family moved to a new house. The failure in discipline that attended the departure of the 51st Defense Battalion from Montford Point led to the replacement of Lieutenant Colonel Stephenson, who had built the unit and earned the respect of its men, by Colonel Curtis W. LeGette. The new commanding officer, a native of South Carolina and a Marine since 1910, had fought in France during World War I and been wounded at Blanc Mont in October 1918. His most recent assignment was as commanding officer of the 7th Defense Battalion in the Ellice Islands. Not only was LeGette replacing a popular commander, he got off to a bad start. In his first speech to the assembled battalion, he made the mistake of invoking the phrase "you people" — frequently used by officers when addressing their white units — but in this instance his choice of "you" instead of "we" convinced some of the African-Americans that their new commanding officer considered them outsiders rather than real Marines.

|