| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

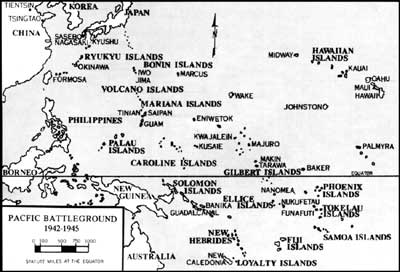

THE RIGHT TO FIGHT: African-American Marines in World War II by Bernard C. Nalty The 51st Defense Battalion at War Because they were replacing the 7th Defense Battalion, LeGette's former command, already established in the Ellice group, the black Marines turned in all the heavy equipment they had brought with them from Montford Point and boarded the merchantman SS Meteor, which sailed from San Diego on 11 February 1944. Less than a month had elapsed since the last train left North Carolina on the first leg of the journey to war. While Meteor steamed toward the Ellice Islands, the 51st Defense Battalion divided into two components. Detachment A, led by Lieutenant Colonel Gould P. Groves, the executive officer, would garrison Nanomea Island, while the rest of the battalion, under Colonel LeGette, manned the defenses of Funafuti and nearby Nukufetau. By 27 February, the 51st completed the relief of the 7th Defense Battalion, taking over the white unit's weapons and equipment. One of the African-American Marines, upon first experiencing the isolation that surrounded him, suggested that the departing whites "were never so glad to see black people in their lives." A flurry of action briefly dispelled the feeling of loneliness. On 28 March, crews of the 155mm guns at Nanomea responded to the report of a prowling submarine by firing 11 rounds, but the Japanese craft, if actually present escaped unscathed.

Colonel LeGette, who maintained his headquarters at Funafuti, received a letter from the Commandant of the Marine Corps calling attention to the poor condition of the trucks and weapons his battalion had left behind in California. This chilling message tended to confirm LeGette's reservations about the unit. His concerns focused on administrative procedures and the maintenance of equipment, activities that required close supervision by experienced noncommissioned officers, who were scarce in the unit. The battalion commander sought to fix the blame for the shortcomings that had been revealed and to correct them.

To fix responsibility LeGette convened a board of investigation that condemned his predecessor for failing to whip the battalion into shape and recommended a trial by courtmartial, but Stephenson responded with a spirited rejoinder that fore stalled legal action. Most of the problems that troubled LeGette stemmed from something over which Stephenson had no control — the absence of a cadre of veteran black noncommissioned officers, itself the result of racial segregation and the exclusion of African-Americans from the prewar Marine Corps. Despite his successor's complaints, Stephenson considered the 51st Defense Battalion "the finest organization in the whole Negro program in the Marine Corps." Since the men of the unit did not know the details of the controversy involving the two commanders, morale remained high.

LeGette proposed a course of action to correct the flaws he had perceived. His remedy, however, included measures rendered impossible because of the demands of other units for officers and the policy of maintaining segregation in the enlisted force. He would have increased the number of white officers and warrant officers assigned to the unit and avoided the "occupational neurosis" resulting from service with blacks by replacing those officers who desired to leave the battalion. He further recommended the replacement of enlisted men in Categories IV and V with individuals who had scored better in the classification tests, a goal that could have been achieved only by raiding other black units. The 51st Defense Battalion remained in the Ellice Islands roughly six months. When the black Marines received orders to depart, they carefully cleaned and checked the equipment inherited from the 7th Defense Battalion before turning everything over to the white 10th Defense Battalion. LeGette's unit set sail on 8 September 1944 for Eniwetok Atoll, a vast anchorage kept under sporadic surveillance, and occasionally harassed, by Japanese aircraft. The battalion stood ready to meet this threat from the skies, since it had reorganized two months earlier as an antiaircraft unit, losing its 155mm guns but adding a fourth 90mm battery and exchanging its machine guns and 20mm weapons for a second 40mm battery. The restructured unit kept its searchlights and radar. While the black Marines manned positions on four of the atoll's islands, Colonel LeGette on 13 December handed over the battalion to Lieutenant Colonel Groves. A member of the unit, Herman Darden, Jr., remembered that the departing commander "took us out on dress parade before he left, and stood there with tears in his eyes and told us . . ., 'You have shown me that you can soldier with the best of 'em.'" The possibility of action lingered into 1945, kept alive by a report of marauding submarines and the possibility of aerial attack. One night, while the men of the 90mm antiaircraft group were watching a movie, the film abruptly stopped. Condition Red; Japanese aircraft were on the way. "I never saw such jubilation in my life," recalled Darden, "for every one responded eagerly. A Marine on a working party unloading ammunition might grumble about lifting a single 90mm round, but with combat seemingly minutes away, men were running around with one under each arm." By dawn, the alert had ended; not even one Japanese aircraft tested the battalions gun crews. "And from that high point on," Darden said, "the mental attitude seemed to dwindle." Routine settled over Eniwetok, enveloping the unit that Groves now commanded. As one of its sergeants phrased it, "routine got boresome," punctuated only by the occasional crash or forced landing by American planes. A major change occurred on 12 June 1945, when the battalion commander formed a 251-man composite group, under Major William M. Tracy, for duty at Kwajalein Atoll. Two days later, the group — consisting of a battery of 90mm guns, a 40mm platoon, and four search light sections — boarded an LST for the voyage. The contingent saw no combat at Kwajalein, nor did the remainder of the battalion at Eniwetok.

|