| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

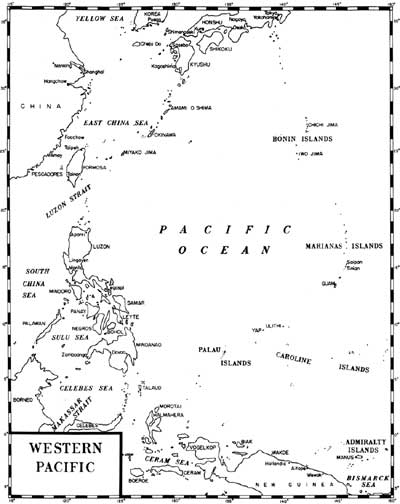

THE FINAL CAMPAIGN: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) Countdown to 'Love-Day' The three-month-long battle of Okinawa covered a 700-mile arc from Formosa to Kyushu and involved a million combatants — Americans, Japanese, British, and native Okinawans. With a magnitude that rivaled the Normandy invasion the previous June, the battle of Okinawa was the biggest and costliest single operation of the Pacific War. For each of its 82 days of combat, the battle would claim an average of 3,000 lives from the antagonists and the unfortunate noncombatants. Imperial Japan by spring 1945 has been characterized as a wounded wild animal, enraged, cornered, and desperate. Japanese leaders knew fully well that Okinawa in U.S. hands would be transformed into a gigantic staging base — "the England of the Pacific" — for the ultimate invasion of the sacred homeland. They were willing to sacrifice everything to avoid the unspeakable disgrace of unconditional surrender and foreign occupation.

Okinawa would therefore present the U.S. Navy with its greatest operational challenge: protecting an enormous and vulnerable amphibious task force tethered to the beachhead against the ungodliest of furies, the Japanese kamikazes. Equally, Okinawa would test whether U.S. amphibious power projection had truly come of age — whether Americans in the Pacific Theater could plan and execute a massive assault against a large, heavily defended land-mass, integrate the tactical capabilities of all services, fend off every imaginable form of counterattack, and maintain operational momentum ashore. Nor would Operation Iceberg be conducted in a vacuum. Action preliminary to the invasion would kick-off at the same time that major campaigns in Iwo Jima and the Philippines were still being wrapped up, a reflection of the great expansion of American military power in the Pacific, yet a further strain on Allied resources. But as expansive and dramatic as the Battle of Okinawa proved to be, both sides clearly saw the contest as a foretaste of even more desperate fighting to come with the inevitable invasion of the Japanese home islands. Okinawa's proximity to Japan — well within medium bomber and fighter escort range — and its militarily useful ports, airfields, anchorages, and training areas — made the skinny island an imperative objective for the Americans, eclipsing their earlier plans for the seizure of Formosa for that purpose.

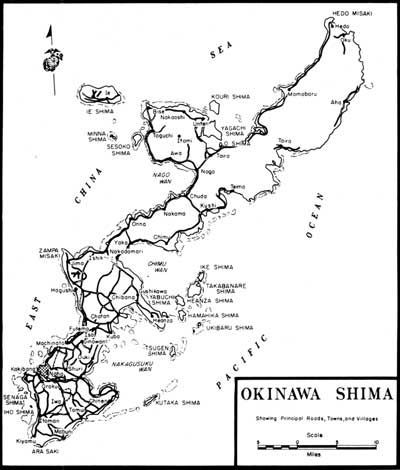

Okinawa, the largest of the Ryukyuan Islands, sits at the apex of a triangle almost equidistant to strategic areas. Kyushu is 350 miles to the north; Formosa 330 miles to the southwest; Shanghai 450 miles to the west. As so many Pacific battlefields, Okinawa had a peaceful heritage. Although officially one of the administrative prefectures of Japan, and Japanese territory since being forcibly seized in 1879, Okinawa prided itself on its distinctive differences, its long Chinese legacy and Malay influence, and a unique sense of community. The Japanese Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ) in Tokyo did little to fortify or garrison Okinawa in the opening years of the Pacific War. With the American seizure of Saipan in mid-1944, however, IGHQ began dispatching reinforcements and fortification materials to critical areas within the "Inner Strategic Zone," including Iwo Jima, Peleliu, the Philippines, and Okinawa.

On Okinawa, IGHQ established a new field army, the Thirty-second Army, and endeavored to funnel trained components to it from elsewhere along Japan's great armed perimeter in China, Manchuria, or the home islands. But American submarines exacted a deadly toll. On 29 June 1944, the USS Sturgeon torpedoed the transport Toyama Maru and sank her with the loss of 5,600 troops of the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade, bound for Okinawa. It would take the Japanese the balance of the year to find qualified replacements. By October 1944 the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff had recognized the paramount strategic value of the Ryukyus and issued orders to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet/Commander, Pacific Ocean Areas, to seize Okinawa immediately after the Iwo Jima campaign. The JCS directed Nimitz to "seize, occupy, and defend Okinawa" — then transform the captured island into an advance staging base for the invasion of Japan. Nimitz turned once again to his most veteran commanders to execute the demanding mission. Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, victor of Midway, the Gilberts, Marshalls, Marianas, and the Battle of the Philippine Sea, would command the U.S. Fifth Fleet, arguably the most powerful armada of warships ever assembled. Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, gifted and irascible veteran of the Solomons and Central Pacific landings, would again command all amphibious forces under Spruance. But Turner's military counterpart would no longer be the familiar old war-horse, Marine Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith. Iwo Jima had proven to be Smith's last fight. Now the expeditionary forces had grown to the size of a field army with 182,000 assault troops. Army Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., the son of a Confederate general who fought against U.S. Grant at Fort Donaldson in the American Civil War, would command the newly created U.S Tenth Army.

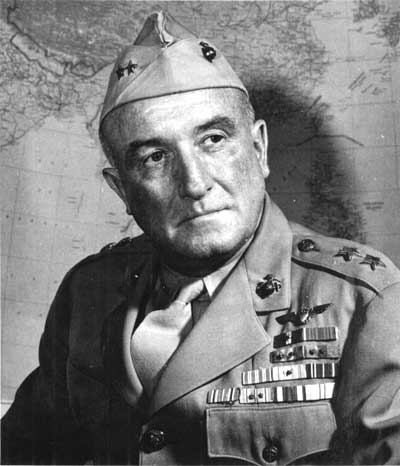

General Buckner took pains to ensure that the composition of the Tenth Army staff reflected his command's multiservice composition. Thirty-four Marine officers served on Buckner's staff, for example, including Brigadier General Oliver P. Smith, USMC, as his Marine Deputy Chief of Staff. As Smith later remarked, "the Tenth Army became in effect a joint task force under CINCPOA." Six veteran divisions — four Army, two Marine — would comprise Buckner's landing force, with a division from each service marked for reserve duty. Here was another indication of the growth of U.S. amphibious power in the Pacific. Earlier, the Americans had forcibly landed one infantry division at Guadalcanal, two each in the Gilberts, Marshalls, and Palaus, and three each at Saipan and Iwo. By spring 1945, Spruance and Buckner could count on eight experienced divisions, above and beyond those still committed at Iwo or Luzon. Buckner's Tenth Army had three major operational components. Army Major General John R. Hodge commanded the XXIV Corps, comprised of the 7th, 77th, and 96th Infantry Divisions, with the 27th Infantry Division in floating reserve, and the 81st Infantry Division in area reserve. Marine Major General Roy S. Geiger commanded the III Amphibious Corps (IIIAC), comprised of the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions, with the 2d Marine Division in floating reserve. Both corps had recent campaign experience, the XXIV in Leyte, the IIIAC at Guam and Peleliu. The third major component of Buckner's command was the Tactical Air Force, Tenth Army, commanded by Marine Major General Francis P. Mulcahy, who also commanded the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing. His Fighter Command was headed by Marine Brigadier General William J. Wallace. The Senior Marine Commanders The four senior Marine commanders at Okinawa were seasoned combat veterans and well versed in joint service operations — qualities that enhanced Marine Corps contributions to the success of the U.S. Tenth Army. Major General Roy S. Geiger, USMC, commanded III Amphibious Corps. Geiger was 60, a native of Middleburg, Florida, and a graduate of both Florida State Normal and Stetson University Law School. He enlisted in the Marines in 1907 and became a naval aviator (the fifth Marine to be so designated) in 1917. Geiger flew combat missions in France in World War I in command of a squadron of the Northern Bombing Group. At Guadalcanal in 1942 he commanded the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, and in 1943 he assumed command of I Marine Amphibious Corps (later IIIAC) on Bougainville, and for the invasions of Guam, and the Palaus. Geiger had a nose for combat; even on Okinawa he conducted frequent visits to the front lines and combat outposts. On two occasions he "appropriated" an observation plane to fly over the battlefield for a personal reconnaissance. With the death of General Buckner, Geiger assumed command of the Tenth Army, a singular and fitting attainment, and was immediately promoted to lieutenant general by the Marine Corps. Geiger subsequently relieved General Holland M. Smith as Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific. In that capacity, he was one of the very few Marines invited to attend the Japanese surrender ceremony on board USS Missouri on 2 September 1945 in Tokyo Bay. Geiger also served as an observer to the 1946 atomic bomb tests in Bikini Lagoon, and his somber evaluation of the vulnerability of future surface ship-to-shore assaults to atomic munitions spurred Marine Corps development of the transport helicopter. General Geiger died in 1947.

Major General Pedro A. del Valle, USMC, commanded the 1st Marine Division. Del Valle was 51, a native of San Juan, Puerto Rico, and a 1915 graduate of the Naval Academy. He commanded the Marine Detachment on board the battleship Texas in the North Atlantic during World War I. Subsequent years of sea duty and expeditionary campaigns in the Caribbean and Central America provided del Valle a vision of how Marines might better serve the Navy and their country in war. In 1931 Brigadier General Randolph C. Berkeley appointed then-Major del Valle to the "Landing Operations Text Board" in Quantico, the first organizational step taken by the Marines (with Navy gun fire experts) to develop a working doctrine for amphibious assault. His provocative essay, "Ship-to-Shore in Amphibious Operations," in the February 1932 Marine Corps Gazette, challenged his fellow officers to think seriously of executing an opposed landing. A decade later, del Valle, a veteran artilleryman, commanded the 11th Marines with distinction during the campaign for Guadalcanal. More than one surviving Japanese marveled at the "automatic artillery" of the Marines. Del Valle then commanded corps artillery for IIIAC at Guam before assuming command of "The Old Breed" for Okinawa. General del Valle died in 1978.

Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., USMC, commanded the 6th Marine Division. Shepherd was 49, a native of Norfolk, Virginia, and a 1917 graduate of Virginia Military Institute. He served with great distinction with the 5th Marines in France in World War I, enduring three wounds and receiving the Navy Cross. Shepherd became one of those rare infantry officers to hold command at every possible echelon, from rifle platoon to division. Earlier in the Pacific War, he commanded the 9th Marines, served as Assistant Commander of the 1st Marine Division at Cape Gloucester, and commanded the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade at Guam. In September 1944 at Guadalcanal, he became the first commanding general of the newly formed 6th Marine Division and led it with great valor throughout Okinawa. After the war, he served as Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, during the first two years of the Korean War, and subsequently became 20th Commandant of the Corps. General Shepherd died in 1990.

Major General Francis P Mulcahy, USMC, commanded both the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing and the Tenth Army Tactical Air Force (TAF). Mulcahy was 51, a native of Rochester, New York, and a graduate of Notre Dame University. He was commissioned in 1917 and attended naval flight school that same year. Like Roy Geiger, Mulcahy flew bombing missions in France during World War I. He became one of the Marine Corps pioneers of close air support to ground operations during the inter-war years of expeditionary campaigns in the Caribbean and Central America. At the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Mulcahy was serving as an observer with the British Western Desert Air Force in North Africa. He deployed to the Pacific in command of the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing. In the closing months of the Guadalcanal campaign, Mulcahy served with distinction in command of Allied Air Forces in the Solomons. He volunteered for the TAF assignment, deployed ashore early to the freshly captured air fields at Yontan and Kadena, and worked exhaustively to coordinate the combat deployment of his joint-service aviators against the kamikaze threat to the fleet and in support of the Tenth Army in its protracted inland campaign. For his heroic accomplishments in France in 1918, the Solomons in 1942-43, and at Okinawa, he received three Distinguished Service Medals. General Mulcahy died in 1973.

The Marine components staged for Iceberg in scattered locations. The 1st Marine Division, commanded by Major General Pedro A. del Valle, had returned from Peleliu to "pitiful Pavuvu" in the Russell Islands to prepare for the next campaign. The 1st Division had also been the first to deploy to the Pacific and had executed difficult amphibious campaigns at Guadalcanal, Cape Gloucester, and Peleliu. At least one-third of the troops were veterans of two of those battles; another third had experienced at least one. Tiny Pavuvu severely limited work-up training, but a large-scale exercise in nearby Guadalcanal enabled the division to integrate its newcomers and returning veterans. General del Valle, a consummate artillery officer, ensured that his troops conducted tank-infantry training under the protective umbrella of supporting howitzer fires. The 6th Marine Division became the only division to be formed overseas in the war when Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., activated the colors and assumed command in Guadalcanal in September 1944. The unit may have been new, but hardly a greenhorn could be found in its leadership ranks. Many former Mariner raiders with combat experience in the Solomons comprised the heart of the 4th Marines. The regiment had also landed at Emirau and Guam. The 22d Marines had combat experience at Eniwetok and Guam. And while the 29th Marines comprised a relatively new infantry regiment, its 1st Battalion had played a pivotal role in the Saipan campaign. General Shepherd used his time and the more expansive facilities on Guadalcanal to conduct progressive, work-up training, from platoon to regimental level. Looking ahead to Okinawa, Shepherd emphasized rapid troop deployments, large-scale operations, and combat in built-up areas. The 2d Marine Division, commanded by Major General LeRoy R Hunt, had returned to Saipan after completing the conquest of Tinian. There the division absorbed up to 8,000 replacements and endeavored to train for a frustratingly varied series of mission assignments as, in effect, a strategic reserve. The unit already possessed an invaluable lineage in the Pacific War — Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan, and Tinian — and its mere presence in Ryukyus' waters would constitute a formidable "amphibious force-in-being" which would distract the Japanese on Okinawa. Yet the division would pay a disproportionate price for its bridesmaid's role in the coming campaign. The Marine divisions preparing to assault Okinawa experienced yet another organizational change, the fourth of the war. Headquarters Marine Corps (HQMC), constantly reviewing the lessons learned in the war to date, had just completed a series of revisions to the tables of organization and equipment for the division and its components. Although the "G-Series" T/O would not become official until a month after the landing, the divisions had already complied with most of the changes. The overall size of each division increased from 17,465 to 19,176. This growth reflected the addition of an assault signal company, a rocket platoon (the "Buck Rogers Men"), a war dog platoon, and — significantly — a 55-man assault platoon in each regimental headquarters. Artillery, motor transport, and service units received slight increases. So did the machine gun platoons in each rifle company. The most timely weapons change occurred with the replacement of the 75mm "half-tracks" with the newly developed M-7 105mm self-propelled howitzer — four to each regiment. Purists in the artillery regiments tended to sniff at these weapons, deployed by the infantry not as massed howitzers but rather as direct-fire, open-sights "siege guns" against Okinawa's thousands of fortified caves, but the riflemen soon swore by them. Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, backed up these last-minute changes by providing the quantities of replacements required, so that each assault division actually landed at full tables of organization (T/O) strength, plus the equivalent of two replacement drafts each. Sometimes the skills required did not match the requirement, however. Some of the artillery regiments had to absorb a flood of radar technicians and antiaircraft artillery gunners from the old Defense Battalions at the last moment. But by and large, the manpower and equipment shortfalls which had beset many early operations had been overcome by the time of embarkation for the Okinawa campaign.

Surprisingly for this late in the war, operational intelligence proved less than satisfactory prior to the Okinawa landing. Where pre-assault combat intelligence had been superb in the earlier operations at Tarawa (the apogean neap tide notwithstanding) and Tinian, here at Okinawa, the landing force did not have accurate figures of the enemy's numbers, weapons, and disposition, or intelligence of his abilities. Part of the problem lay in the fact that cloud cover over the island most of the time prevented accurate and complete photo-reconnaisance of the target area. In addition, the incredible digging skills of the defending garrison and the ingenuity of the Japanese commander conspired to disguise the island's defenses.

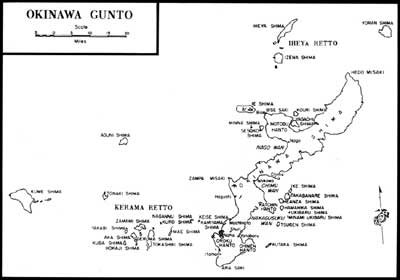

The island of Okinawa is 60 miles long, but only the lower third contained the significant military objectives of airfields, ports, and anchorages. When Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima assumed command of the Thirty-second Army in August 1944, he quickly realized this and decided to concentrate his forces in the south. He also decided, regretfully, to refrain from contesting the likely American landings along the broad beaches at Hagushi on the southwest coast. Doing so would forfeit the prize airfields of Yontan and Kadena, but it would permit Ushijima to conserve his forces and fight the only kind of battle he thought had a chance for the Empire: a defense in depth, largely underground and thus protected from the overwhelming American superiority in supporting arms. This was the attrition/cave warfare of the more recent defenses at Biak, Peleliu, and Iwo Jima. Each had exacted a frightful cost on the American invaders. Ushijima sought to duplicate this philosophy in spades. He would go to ground, sting the Americans with major-caliber gunfire from his freshly excavated "fire-port" caves, bleed them badly, bog down their momentum — and in so doing provide the Imperial Army and Navy air arms the opportunity to destroy the Fifth Fleet by massed kamikaze attacks. To achieve this strategy, Ushijima had upwards of 100,000 troops on the island, including a generous number of Okinawan conscripts, the Home Guard known as Boeitai. He also had a disproportionate number of artillery and heavy weapon units in his command. The Americans in the Pacific would not encounter a more formidable concentration of 150mm howitzers, 120mm mortars, 320mm mortars, and 47mm antitank guns. Finally, Ushijima also had time. The American strategic decisions to assault the Philippines, Peleliu, and Iwo Jima before Okinawa gave the Japanese garrison on Okinawa seven months to develop its defenses around the Shuri epicenter. Americans had already seen what the Japanese could do in terms of fortifying a position within an incredibly short time. At Okinawa, they achieved a masterpiece. Working entirely with hand tools — there was not a single bulldozer on the island — the garrison dug miles of underground fighting positions, literally honey-combing southern Okinawa's ridges and draws, and stocked each successive position with reserves of ammunition, food, water, and medical supplies. The Americans expected a ferocious defense of the Hagushi beaches and the airfields just beyond, followed by a general counterattack — then the battle would be over except for mop-up patrolling. They could not have been more misinformed. The U.S. plan of attack called for advance seizure of the Kerama Retto Islands off the southwest coast, several days of preliminary air and naval gunfire bombardment, a massive four-division assault over the Hagushi Beaches (the Marines of III AC on the north, the soldiers of XXIV Corps on the south). Meanwhile, the 2d Marine Division with a separate naval task unit would endeavor to duplicate opposite the Minatoga Beaches on Okinawa's southeast coast its successful amphibious feint off Tinian. Love-Day (selected from the existing phonetic alphabet in order to avoid planning confusion with "D-Day" being planned for Iwo Jima) would occur on 1 April 1945. Hardly a man failed to comment on the obvious irony: it was April Fool's Day and Easter Sunday — which would prevail?

The U.S. Fifth Fleet constituted an awesome sight as it sortied from Ulithi Atoll and a dozen other ports and anchorages to steam towards the Ryukyus. Those Marines who had returned to the Pacific from the original amphibious offensive at Guadalcanal some 31 months earlier marveled at the profusion of assault ships and landing craft. The new vessels covered the horizon, a mind-boggling sight.

On 26 March, the 77th Infantry Division kicked off the campaign by its skillful seizure of the Kerama Retto, a move which surprised the Japanese and produced great operational dividends. Admiral Turner now had a series of sheltered anchorages to repair ships likely to be damaged by Japanese air attacks — and already kamikazes were exacting a toll. The soldiers also discovered the main cache of Japanese suicide boats, nearly 300 power boats equipped with high-explosive rams intended to sink the thin-skinned troop transports in their anchorages off the west coast of Okinawa. The Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, Force Reconnaissance Battalion, commanded by Major James L. Jones, USMC, preceded each Army landing with stealthy scouting missions the preceding night. Jones' Marines also scouted the barren sand spits of Keise Shima and found them undefended. With that welcome news, the Army landed a battery of 155mm "Long Toms" on the small islets and soon added their considerable firepower to the naval bombardment of the south west coast of Okinawa. Meanwhile, Turner's minesweepers had their hands full clearing approach lanes to the Hagushi Beaches. Navy Underwater Demolition Teams, augmented by Marines, blew up hundreds of man-made obstacles in the shallows. And in a full week of preliminary bombardment, the fire support ships delivered more than 25,000 rounds of five-inch shells or larger. The shelling produced more spectacle than destruction, however, because the invaders still believed General Ushijima's forces would be arrayed around the beaches and air fields. A bombardment of that scale and duration would have saved many lives at Iwo Jima; at Okinawa this precious ordnance produced few tangible results. A Japanese soldier observing the huge armada bearing down on Okinawa wrote in his diary, "it's like a frog meeting a snake and waiting for the snake to eat him." Tensions ran high among the U.S. transports as well. The 60mm mortar section of Company K, 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, learned that casualty rates on L-Day could reach 80-85 percent. "This was not conducive to a good night's sleep," remarked Private First Class Eugene B. Sledge, a veteran of the Peleliu landing. On board another transport, combat correspondent Ernie Pyle sat down to a last hot meal with the enlisted Marines: "Fattening us up for the kill; the boys say," he reported. On board a nearby LST, a platoon commander rehearsed his troops in the use of home-made scaling ladders to surmount a concrete wall just beyond the beaches. "Remember, don't stop — get off that wall, or somebody's gonna get hurt."

|