| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

THE FINAL CAMPAIGN: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) Assault on Shuri The Tenth Army's Action Report for the battle of Okinawa paid this understated compliment to the Thirty-second Army's defensive efforts: "The continued development and improvement of cave warfare was the most outstanding feature of the enemy's tactics on Okinawa." In their decision to defend the Shuri highlands across the southern neck of the island, General Ushijima and his staff had selected the terrain that would best dominate two of the island's strategic features: the port of Naha to the west, and the sheltered anchorage of Nakagusuku Bay (later Buckner Bay) to the east. As a consequence, the Americans would have to force their way into Ushijima's preregistered killing zones to achieve their primary objectives. Everything about the terrain favored the defenders. The convoluted topography of ridges, draws, and escarpments served to compartment the battlefield into scores of small firefights, while the general absence of dense vegetation permitted the defenders full observation and interlocking supporting fires from intermediate strongpoints. As at Iwo Jima, the Japanese Army fought largely from underground positions to offset American dominance in supporting arms. And even in the more accessible terrain, the Japanese took advantage of the thousands of concrete, lyre-shaped Okinawan tombs to provide combat outposts. There were blind spots in the defenses, to be sure, but finding and exploiting them took the Americans an inordinate amount of time and cost them dearly.

The bitterest fighting of the campaign took place within an extremely compressed battlefield. The linear distance from Yonabaru on the east coast to the bridge over the Asa River above Naha on the opposite side of the island is barely 9,000 yards. General Buckner initially pushed south with two Army divisions abreast. By 8 May he had doubled this commitment: two Army divisions of the XXIV Corps on the east, two Marine divisions of IIIAC on the west. Yet each division would fight its own desperate, costly battles against disciplined Japanese soldiers defending elaborately fortified terrain features. There was no easy route south. By eschewing the amphibious flanking attack in late April, General Buckner had fresh divisions to employ in the general offensive towards Shuri. Thus, the 77th Division relieved the 96th in the center, and the 1st Marine Division began relieving the 27th Division on the west. Colonel Kenneth B. Chappell's 1st Marines entered the lines on the last day of April and drew heavy fire from the moment they approached. By the time the 5th Marines arrived to complete the relief of 27th Division elements on 1 May, Japanese gunners supporting the veteran 62d Infantry Division were pounding anything that moved. "It's hell in there, Marine," a dispirited soldier remarked to Private First Class Sledge as 3/5 entered the lines. "I know," replied Sledge with false bravado, "I fought at Peleliu." But soon Sledge was running for his life:

General del Valle assumed command of the western zone at 1400 on 1 May and issued orders for a major attack the next morning. That evening a staff officer brought the general a captured Japanese map, fully annotated with American positions. With growing uneasiness, del Valle realized his opponents already knew the 1st Marine Division had entered the fight.

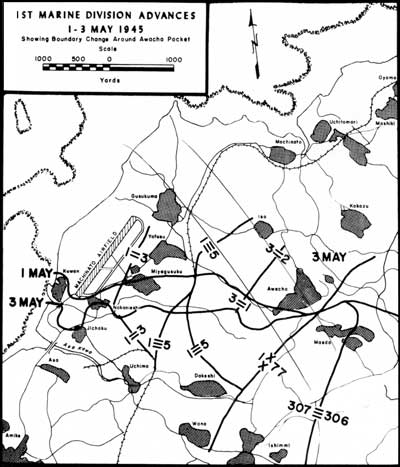

The division attacked south the next day into broken country there after known as the Awacha Pocket. For all their combat prowess, however, the Marines proved to be no more immune to the unrelenting storm of shells and bullets than the soldiers they had relieved. The disappointing day also included several harbingers of future conditions. First, it rained hard all day. Second, as soon as the 5th Marines seized the nearest high ground they came under such intense fire from adjacent strongpoints and from higher ground within the 77th Division's zone to the immediate southeast they had to withdraw. Third, the Marines spent much of the night engaged in violent hand-to-hand fighting with scores of Japanese infiltrators. "This," said one survivor, "is going to be a bitch." The Peleliu veterans in the ranks of the 1st Marine Division were no strangers to cave warfare. Clearly, no other division in the campaign could claim such a wealth of practical experience. And while nothing on Okinawa could match the Umurbrogol's steep cliffs, heavy vegetation, and endless array of fortified ridges, the "Old Breed" in this battle faced a smarter, more numerous foe who had more artfully prepared each wrinkle in the moonscape. In overcoming the sequential barriers of Awacha, Dakeshi, and Wana, the 1st Marine Division faced four straight weeks of hell. The funneling effects of the cliffs and draws reduced most attacks to brutal frontal assaults by fully-exposed tank-infantry-engineer teams. General del Valle characterized this small unit fighting as "a slugging match with but temporary and limited opportunity to maneuver."

General Buckner captured the fancy of the media with his metaphor about the "blowtorch and corkscrew" tactics needed for effective cave warfare, but this was simply stating the obvious to the Army veterans of Biak and the Marine veterans of Peleliu and Iwo Jima. Flamethrowers were represented by the blow torch, demolitions, by the cork screw — but both weapons had to be delivered from close range by tanks and the exposed riflemen covering them. On 3 May the rains slowed and the 5th Marines resumed its assault, this time taking and holding the first tier of key terrain in the Awacha Pocket. But the systematic reduction of this strongpoint would take another full week of extremely heavy fighting. Fire support proved excellent. Now it was the Army's time to return the favor of interservice artillery support. In this case, the 27th Division's field artillery regiment stayed on the lines, and with its forward observers and linemen intimately familiar with the terrain in that sector, rendered yeoman service.

At this point an odd thing happened, an almost predictable chink in the Japanese defensive discipline. The genial General Ushijima permitted full discourse from his staff regarding tactical courses of action. Typically, these debates occurred between the impetuous chief of staff, Lieutenant General Isamu Cho, and the conservative operations officer, Colonel Hiromichi Yahara. To this point, Yahara's strategy of a protracted holding action had prevailed. The Thirty-second Army had resisted the enormous American invasion successfully for more than a month. The army, still intact, could continue to inflict high casualties on the enemy for months to come, fulfilling its mission of bleeding the ground forces while the "Divine Wind" wreaked havoc on the fleet. But maintaining a sustained defense was anathema to a warrior like Cho, and he argued stridently for a massive counterattack. Against Yahara's protests, Ushijima sided with his chief of staff.

The greatest Japanese counterattack of 4-5 May proved ill-advised and exorbitant. To man the assault forces, Ushijima had to forfeit his coverage of the Minatoga sector and bring those troops forward into unfamiliar territory. To provide the massing of fires necessary to cover the assault he had to bring most of his artillery pieces and mortars out into the open. And his concept of using the 26th Shipping Engineer Regiment and other special assault forces in a frontal attack, and, at the same time, a waterborne, double envelopment would alert the Americans to the general counteroffensive. Yahara cringed in despair.

The events of 4-5 May proved the extent of Cho's folly. Navy "Flycatcher patrols on both coasts interdicted the first flanking attacks conducted by Japanese raiders in slow-moving barges and native canoes. Near Kusan, on the west coast, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, and the LVT-As of the 3d Armored Amphibian Battalion greeted the invaders trying to come ashore with a deadly fire, killing 700. Further along the coast, 2/1 intercepted and killed 75 more, while the 1st Reconnaissance Company and the war dog platoon tracked down the last 65 hiding in the brush. Meanwhile the XXIV Corps received the brunt of the overland thrust and contained it effectively, scattering the attackers into small groups, hunting them down ruthlessly. The 1st Marine Division, instead of being surrounded and annihilated in accordance with the Japanese plan, launched its own attack instead, advancing several hundred yards. The Thirty-second Army lost more than 6,000 first-line troops and 59 pieces of artillery in the futile counterattack. Ushijima, in tears, promised Yahara he would never again disregard his advice. Yahara, the only senior officer to survive the battle, described the disaster as "the decisive action of the campaign."

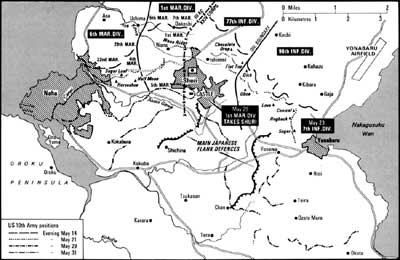

At this point General Buckner decided to make it a four-division front and ordered General Geiger to redeploy the 6th Marine Division south from the Motobu Peninsula. General Shepherd quickly asked Geiger to assign his division to the seaward flank to continue the benefit of direct naval gunfire support. "My G-3, Brute Krulak, was a naval gun fire expert," Shepherd said, noting the division's favorable experience with fleet support throughout the northern campaign. Unspoken was an additional benefit: Shepherd would have only one adjacent unit with which to coordinate fire and maneuver, and a good one at that, the veteran 1st Marine Division. On the morning of 7 May General Geiger regained control of the 1st Marine Division and his Corps Artillery from XXIV Corps and established his forward CP. The next day the 22d Marines relieved the 7th Marines in the lines north of the Asa River. The 1st Marine Division, which had suffered more than 1,400 casualties in its first six days on the lines while trying to cover a very wide front, adjusted its boundaries gratefully to make room for the newcomers.

Yet the going got no easier, even with two full Marine divisions now shoulder-to-shoulder in the west. Heavy rains and fierce fire greeted the 6th Marine Division as its regiments entered the Shuri lines. The situation remained as grim and deadly all along the front. On 9 May, 1/1 made a spirited attack on Hill 60 but lost its commander, Lieutenant Colonel James C. Murray, Jr., to a sniper. Nearby that night, 1/5 engaged in desperate hand-to-hand fighting with a force of 60 Japanese soldiers who appeared like phantoms out of the rocks. The heavy rains caused problems for the 22d Marines in its efforts to cross the Asa River. The 6th Engineers fabricated a narrow foot bridge under intermittent fire one night. Hundreds of infantry raced across before two Japanese soldiers wearing satchel charges strapped to their chests dashed into the stream and blew themselves and the bridge to kingdom come. The engineers then spent the next night building a more substantial Bailey Bridge. Across it poured reinforcements and vehicles, but the tanks played hell traversing the soft mud along both banks — each attempt was an adventure. Yet the 22d Marines were now south of the river in force, an encouraging bit of progress on an otherwise stalemated front.

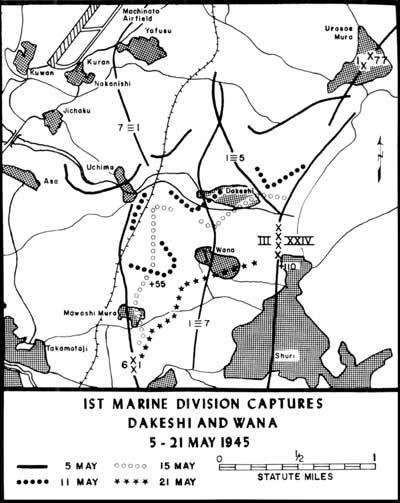

The 5th Marines finally fought clear of the devilish Awacha Pocket on the 10th, ending a week of frustration and point-blank casualties. Now it became the turn of the 7th Marines to engage its own nightmare terrain. Due south of their position lay Dakeshi Ridge. Coincidentally, General Buckner prodded his commanders on the 11th, announcing a renewed general offensive along the entire front. This proclamation may well have been in response to the growing criticism Buckner had been receiving from the Navy and some of the media for his time-consuming attrition strategy. But the riflemen's war had progressed beyond high-level exhortation. The assault troops knew fully what to expect — and what it would likely cost.

The 7th Marines was an experienced outfit and well commanded by Guadalcanal and Bougainville veteran Colonel Edward W. Snedeker. "I was especially fortunate at Okinawa," he said, "in that each of my battalion commanders had fought at Peleliu." Nevertheless, the regiment had its hands full with Dakeshi Ridge. "It was our most difficult mission," said Snedeker. After a day of intense fighting, Lieutenant Colonel John J. Gormley's 1/7 fought its way to the crest of Dakeshi, but had to withdraw under swarming Japanese counterattacks. The next day, Lieutenant Colonel Spencer S. Berger's 2/7 regained the crest and cut down the counterattackers emerging from their reverse-slope bunkers. The 7th Marines were on Dakeshi to stay, another significant breakthrough. "The Old Breed" Marines enjoyed only a brief elation at this achievement because from Dakeshi they could glimpse the difficulties yet to come. In fact, the next 1,200 yards of their advance would eat up 18 days of fighting. In this case, seizing Wana Ridge would be tough, but the most formidable obstacle would be steep, twisted Wana Draw that rambled just to the south, a deadly killing ground, surrounded by towering cliffs pocked with caves, with every possible approach strewn with mines and covered by interlocking fire. "Wana Draw proved to be the toughest assignment the 1st Division was to encounter," reported General Oliver P. Smith. The remnants of the 62d Infantry Division would defend Wana to their deaths. Because the 6th Marine Division's celebrated assault on Sugar Loaf Hill occurred during the same period, historians have not paid as much attention to the 1st Division's parallel efforts against the Wana defenses. But Wana turned out to be almost as deadly a "mankiller" as Sugar Loaf and its bloody environs. The 1st Marines, now led by Colonel Arthur T. Mason, began the assault on the Wana complex on 12 May. In time, all three infantry regiments would take their turn attacking the narrow gorge to the south. The division continued to make full use of its tank battalion. The Sherman medium tanks and attached Army flame tanks were indispensable in both their assault and direct fire support roles (see sidebar). On 16 May, as an indicator, the 1st Tank Battalion fired nearly 5,000 rounds of 75mm and 173,000 rounds of .30-caliber ammunition, plus 600 gallons of napalm. Crossing the floor of the gorge continued to be a heart-stopping race against a gauntlet of enemy fire, however, and progress came extremely slowly. Typical of the fighting was the division's summary for its aggregate progress on 18 May: "Gains were measured by yards won, lost, then won again." On 20 May, Lieutenant Colonel Stephen V. Sabol's 3/1 improvised a different method of dislodging Japanese defenders from their reverse-slope positions in Wana Draw. In five hours of muddy, back breaking work, troops manhandled several drums of napalm up the north side of the ridge. There the Marines split the barrels open, tumbled them down into the gorge, and set them ablaze by dropping white phosphorous grenades in their wake. But each small success seemed to be undermined by the Japanese ability to reinforce and resupply their positions during darkness, usually screened by mortar barrages or small-unit counterattacks. The fighting in such close quarters was vicious and deadly. General del Valle watched in alarm as his casualties mounted daily. The 7th Marines, which lost 700 men taking Dakeshi, lost 500 more in its first five days fighting for the Wana complex. During 16-19 May, Lieutenant Colonel E. Hunter Hurst's 3/7 lost 12 officers among the rifle companies. The other regiments suffered proportionately. Throughout the period 11-30 May, the division would lose 200 Marines for every 100 yards advanced. Heavy rains resumed on 22 May and continued for the next ten days. The 1st Marine Division's sector contained no roads. With his LVTs committed to delivering ammunition and extracting casualties, del Valle resorted to using his replacement drafts to hand-carry food and water to the front lines. This proved less than satisfactory. "You can't move it all on foot," noted del Valle. Marine torpedo bombers flying out of Yontan began air-dropping supplies by parachute, even though low ceilings, heavy rains, and enemy fire made for hazardous duty. The division commander did everything in his power to keep his troops supplied, supported, reinforced, and motivated — but conditions were extremely grim. To the west, the neighboring 6th Marine Division's advance south below the Asa River collided against a trio of low hills dominating the open country leading up to Shuri Ridge. The first of these hills — steep but unassuming — became known as Sugar Loaf. To the southeast lay Half Moon Hill, to the southwest Horseshoe Hill and the village of Takamotoji. The three hills represented a singular defensive complex; in fact they were the western anchor of the Shuri Line. So sophisticated were the mutually supporting defenses of the three hills that an attack on one would prove futile unless the others were simultaneously invested. Colonel Seiko Mita and his 15th Independent Mixed Regiment defended this sector. Its mortars and antitank guns were particularly well sited on Horseshoe. The western slopes of Half Moon contained some of the most effective machine gun nests the Marines had yet encountered. Sugar Loaf itself contained elaborate concrete-reinforced reverse-slope positions. And all approaches to the complex fell within the beaten zone of heavy artillery from Shuri Ridge which dominated the battlefield.

Battlefield contour maps indicate Sugar Loaf had a modest elevation of 230 feet; Half Moon, 220; Horseshoe, 190. In relative terms, Sugar Loaf, though steep, only rose about 50 feet above the northern approaches. This was no Mount Suribachi; its significance lay in the ingenuity of its defensive fortifications and the ferocity with which General Ushijima would counterattack each U.S. penetration. In this regard, the Sugar Loaf complex more closely resembled a smaller version of Iwo Jima's Turkey Knob/Amphitheater sector. As a tactical objective, Sugar Loaf itself lacked the physical dimensions to accommodate anything larger than a rifle company. But eight days of fighting for the small ridge would chew up a series of very good companies from two regiments. Of all the contestants, American or Japanese, who survived the struggle for Sugar Loaf, Corporal James L. Day, a squad leader from Weapons Company, 2/22, had indisputably the "best seat in the house" to observe the battle. In a little-known aspect of this epic story, Day spent four days and three nights isolated in a shell hole on Sugar Loaf's western shoulder. This proved to be an awesome but unenviable experience. Corporal Day received orders on 12 May to recross the Asa River and support the assault of Company G, 2/22, against the small ridge. Day and his squad arrived too late to do much more than cover the fighting withdrawal of the remnants from the summit. The company lost half its number in the day-long assault, including its plucky commander, Captain Owen T. Stebbins, shot in both legs by a Japanese Nambu machine-gunner. Day described Stebbins as "a brave man whose tactical plan for assaulting Sugar Loaf became the pattern for successive units to follow." Concerned about the unrestricted fire from the Half Moon Hill region, Major Henry A. Courtney, Jr., battalion executive officer, took Corporal Day with him on the 13th on a hazardous trek to the 29th Marines to coordinate the forthcoming attacks. With the 29th then committed to protecting 2/22's left flank, Courtney assigned Day and his squad in support of Company F for the next day's assault. Day's rifle squad consisted of seven Marines by that time. On the 14th, they joined Fox Company's assault, reached the hill, scampered up the left shoulder ("you could get to the top in 15 seconds"). Day then received orders to take his squad back around the hill to take up a defensive position on the right (western) shoulder. This took some doing. By late afternoon, Fox Company had been driven off its exposed position on the left shoulder, leaving Day with just two surviving squad-mates occupying a large shell hole on the opposite shoulder.

During the evening, unknown to Day, Major Courtney gathered 45 volunteers from George and Fox companies and led them back up the left shoulder of Sugar Loaf. In hours of desperate, close-in fighting, the Japanese killed Major Courtney and half his improvised force. "We didn't know who they were," recalled Day, "because even though they were only 50 yards away, they were on the opposite side of the crest. Out of visual contact. But we knew they were Marines and we knew they were in trouble. We did our part by shooting and grenading every [Japanese] we saw moving in their direction." Day and his two men then heard the sounds of the remnants of Courtney's force being evacuated down the hill and knew they were again alone on Sugar Loaf. Representing in effect an advance combat outpost on the contested ridge did not particularly bother the 19-year-old corporal. Day's biggest concerns were letting other Marines know they were up there and replenishing their ammo and grenades. "Before dawn I went back down the hill. A couple of LVTs had been trying to deliver critical supplies to the folks who'd made the earlier penetration. Both had been knocked out just north of the hill. I was able to raid those disabled vehicles several times for grenades, ammo, and rations. We were fine." On 15 May, Day and his men watched another Marine assault develop from the northeast. Again there were Marines on the eastern crest of the hill, but fully exposed to raking fire from Half Moon and mortars from Horseshoe. Day's Marines directed well-aimed rifle fire into a column of Japanese running towards Sugar Loaf from Horseshoe, "but we really needed a machine gun." Good fortune provided a .30-caliber, air-cooled M1919A4 in the wake of the retreating Marines. But as soon as Day's gunner placed the weapon in action on the forward parapet of the hole, a Japanese 47mm crew opened up from Horseshoe, killing the Marine and destroying the gun. Now there were just two riflemen on the ridgetop. Tragedy also struck the 1st Battalion, 22d Marines, on the 15th. A withering Japanese bombardment caught the command group assembled at their observation post planning the next assault. Shellfire killed the commander, Major Thomas J. Myers, and wounded every company commander, as well as the CO and XO of the supporting tank company. Of the death of Major Myers, General Shepherd exclaimed, "It's the greatest single loss the Division has sustained. Myers was an outstanding leader." Major Earl J. Cook, battalion executive officer, took command and continued attack preparations. The division staff released this doleful warning that midnight: "Because of the commanding ground which he occupies the enemy is able to accurately locate our OPs and CPs. The dangerous practice of permitting unnecessary crowding and exposure in such areas has already had serious consequences." The warning was meaningless. Commanders had to observe the action in order to command. Exposure to interdictive fire was the cost of doing business as an infantry battalion commander. The next afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel Jean W. Moreau, commanding 1/29, received a serious wound when a Japanese shell hit his observation post squarely. Major Robert P. Neuffer, Moreau's exec, assumed command. Several hours later a Japanese shell wounded Major Malcolm "O" Donohoo, commanding 3/22. Major George B. Kantner, his exec, took over. The battle continued. The night of 15-16 seemed endless to Corporal Day and his surviving squadmate, Private First Class Dale Bertoli. "The Japs knew we were the only ones up there and gave us their full attention. We had plenty of grenades and ammo, but it got pretty hairy." The south slope of Sugar Loaf is the steepest. The Japanese would emerge from their reverse slope caves, but they faced a difficult ascent to get to the Marines on the military crest. Hearing them scramble up the rocks alerted Day and Bertoli to greet them with grenades. Those of the enemy who survived this mini-barrage would find themselves backlit by flares as they struggled over the crest. Day and Bertoli, back to back against the dark side of the crater, shot them readily.

"The 16th was the day I thought Sugar Loaf would fall," said Day. He and Bertoli hunkered down as Marine tanks, artillery, and mortars pounded the ridge and its supporting bastions. "We looked back and see the whole battle shaping up, a great panorama." This was the turn of 1/3/22, well supported by tanks. But Day could also see that the Japanese fires had not slackened at all. "The real danger at Sugar Loaf was not the hill itself, where we were, but in a 300-yard by 300-yard killing zone which the Marines had to cross to approach the hill from our lines to the north . . . . It was a dismal sight, men falling, tanks getting knocked out . . . . the division probably suffered 600 casualties that day. In retrospect, the 6th Marine Division considered 16 May to be "the bitterest day of the entire campaign." By then the 22d Marines was down to 40 percent effectiveness and General Shepherd relieved it with the 29th Marines. He also decided to install fresh leadership in the regiment, replacing the commander and executive officer with the team of Colonel Harold C. Roberts and Lieutenant Colonel August C. Larson. The weather cleared enough during the late afternoon of the 16th to enable Day and Bertoli to see well past Horseshoe Hill, "all the way to the Asato River." The view was not encouraging. Steady columns of Japanese reinforcements streamed northward, through Takamotoji village, towards the contested battlefield. "We kept firing on them from 500 yards away," still maintaining the small but persistent thorn in the flesh of the Japanese defenses. Their rifle fire attracted considerable attention from prowling squads of Japanese raiders that night. "They came at us from 2130 on," recalled Day, "and all we could do was keep tossing grenades and firing our M-1s." Concerned Marines north of Sugar Loaf, hearing the nocturnal ruckus, tried to assist with mortar fire. "This helped, but it came a little too close." Both Day and Bertoli were wounded by Japanese shrapnel and burned by "friendly" white phosphorous.

Early on the 17th a runner from the 29th Marines scrambled up to the shell-pocked crater with orders for the two Marines to "get the hell out." A massive bombardment by air, naval gunfire, and artillery would soon saturate the ridge in preparation of a fresh assault. Day and Bertoli readily complied. Exhausted, reeking, and partially deafened, they stumbled back to safety and an intense series of debriefings by staff officers. Meanwhile, a thundering bombardment crashed down on the three hills. The 17th of May marked the fifth day of the battle for Sugar Loaf. Now it was the turn of Easy Company, 2/29, to assault the complex of defenses. No unit displayed greater valor, yet Easy Company's four separate assaults fared little better than their many predecessors. At midpoint of these desperate assaults, the 29th Marines reported to division, "E Co. moved to top of ridge and had 30 men south of Sugar Loaf; sustained two close-in charges; killed a hell of a lot of Nips; moved back to base to reform and are going again; will take it." But Sugar Loaf would not fall this day. At dusk, after prevailing in one more melee of bayonets, flashing knives, and bare hands against a particularly vicious counterattack, the company had to withdraw. It had lost 160 men.

The 18th of May marked the beginning of seemingly endless rains. Into the start of this soupy mess attacked Dog Company, 2/29, this time supported by more tanks which braved the minefields on both shoulders of Sugar Loaf to penetrate the no-man's land just to the south. When the Japanese poured out of their reverse-slope holes for yet another counterattack, the waiting tanks surprised and riddled them. Dog Company earned the distinction of becoming the first rifle company to hold Sugar Loaf overnight. The Marines would not relinquish that costly ground. But now the 29th Marines were pretty much shot up, and still Half Moon, Horseshoe, and Shuri remained to be assaulted. General Geiger adjusted the tactical boundaries slightly westward to allow the 1st Marine Division a shot at the eastern spur of Horseshoe, and he also released the 4th Marines from Corps reserve. General Shepherd deployed the fresh regiment into the battle on the 19th. The battle still raged. The 4th Marines sustained 70 casualties just in conducting the relief of lines with the 29th Marines. But with Sugar Loaf now in friendly hands, the momentum of the fight began to change. On 20 May, Lieutenant Colonel Reynolds H. Hayden's 1/4 and Lieutenant Colonel Bruno A. Hochmuth's 3/4 made impressive gains on either flank. By day's end, 2/4 held much of Half Moon, while 3/4 had seized a good portion of Horseshoe. As Corporal Day had warned, most Japanese reinforcements funneled into the fight from the southwest, so 3/4 prepared for nocturnal visitors at Horseshoe. These arrived in massive numbers, up to 700 Japanese soldiers and sailors, and surged against 3/4 much of the night. Hochmuth had a wealth of supporting arms: six artillery battalions in direct support at the onset of the attack, and up to 15 battalions at the height of the fighting. Throughout the crisis on Horseshoe, Hochmuth maintained a direct radio link with Lieutenant Colonel Bruce T. Hemphill, commanding 4/15, one of the support artillery firing battalions. This close exchange between commanders reduced the number of short rounds which might have otherwise decimated the defenders and allowed the 15th Marines to provide uncommonly accurate fire on the Japanese. The rain of shells blew great holes in the ranks of every Japanese advance; Marine riflemen met those who survived at bayonet point. The counterattackers died to the man.

Even with Hochmuth's victory the protracted battle of Sugar Loaf lacked a climactic finish. There would be no celebration ceremony here. Shuri Ridge loomed ahead, as did the sniper-infested ruins of Naha. Elements of the 1st Marine Division began bypassing the last of the Wana defenses to the east. The 6th Division slipped westward. Colonel Shapley's 4th Marines crossed the Asa River, now chest-high from the heavy rain fall, on 23 May. The III Amphibious Corps stood poised on the outskirts of Okinawa's capital city. The Army divisions in XXIV Corps matched the Marines' break throughs. On the east coast, the 96th Division seized Conical Hill, the Shuri Line's opposite anchor from Sugar Loaf, after weeks of bitter fighting. The 7th Division, in relief, seized Yonabaru on 22 May. Suddenly, the Thirty-second Army faced the threat of being cut off from both flanks. This time General Ushijima listened to Colonel Yahara's advice. Instead of fighting to the death at Shuri Castle, the army would take advantage of the awful weather and retreat southward to their final line of prepared defenses in the Kiyamu Peninsula. Ushijima executed this withdrawal masterfully. While American aviators spotted and interdicted the south-bound columns, they also reported other columns moving north. General Buckner assumed the enemy was simply rotating units still defending the Shuri defenses. But these northbound troops were ragtag units as signed to conduct a do-or-die rear guard. At this, they were eminently successful.

This was the situation encountered by the 1st Marine Division in its unexpectedly easy advance to Shuri Ridge on 29 May as described in the opening paragraphs. The 5th Marines suddenly possessed the abandoned castle. While General del Valle tried to placate the indignation of the 77th Division commander at the Marines' "intrusion" into his zone, he got another angry call from the Tenth Army. It seems that that the Company A, 1/5 company commander, a South Carolinian, had raised the Stars and Bars of the Confederacy over Shuri Castle instead of the Stars and Stripes. "Every damned outpost and O.P. that could see this started telephoning me," said del Valle, adding, "I had one hell of a hullabaloo converging on my telephone." Del Valle agreed to erect a proper flag, but it took him two days to get one through the intermittent fire of Ushijima's surviving rear guards. Lieutenant Colonel Richard P. Ross, commanding the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, raised this flag in the rain on the last day of May, then took cover. Unlike Sugar Loaf, Shuri Castle could be seen from all over southern Okinawa, and every Japanese gunner within range opened up on the hated colors. The Stars and Stripes fluttered over Shuri Castle, and the fearsome Yonabaru-Shuri-Naha defensive masterpiece had been decisively breached. But the Thirty-second Army remained as deadly a fighting force as ever. It was an army that would die hard defending the final eight miles of shell-pocked, rain-soaked southern Okinawa.

|