| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

THE FINAL CAMPAIGN: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) Closing the Loop The retreating Japanese troops did not escape scot-free from their Shuri defenses. Naval spotter planes located one southbound column and called in devastating fire from a half dozen ships and every available attack aircraft. In short order several miles of the muddy road were strewn with wrecked trucks, field guns, and corpses. General del Valle congratulated the Tactical Air Force: "Thanks for prompt response this afternoon when Nips were caught on road with kimonos down." Successful interdictions, however, remained the exception. Most of Ushijima's Thirty-second Army survived the retreat to its final positions in the Kiyamu Peninsula. The Tenth Army missed a golden opportunity to end the battle four weeks early, but the force, already slowed by heavy rains and deep mud, was simply too ponderous to respond with alacrity.

The infantry slogged southward, cussing the weather but glad to be beyond the Shuri Line. Yet every advance exacted a price. A Japanese sniper killed Lieutenant Colonel Horatio C. Woodhouse, Jr., the competent commander of 2/22, as he led his battalion towards the Kokuba Estuary. General Shepherd, grieving privately at the loss of his younger cousin, replaced him in command with the battalion exec, Lieutenant Colonel John G. Johnson. As the IIIAC troops advanced further south, the Marines began to en counter a series of east-west ridges dominating the open farmlands in their midst. "The southern part of Okinawa," reported Colonel Snedeker, "consists primarily of cross ridges sticking out like bones from the spine of a fish." Meanwhile, the Army divisions of XXIV Corps warily approached two towering escarpments in their zone, Yuza Dake and Yaeju Dake. The Japanese had obviously gone to ground along these ridges and peaks and lay waiting for the American advance.

Rain and mud continued to plague the combatants. One survivor of this segment of the campaign described the battlefields as "a five-mile sea of mud." As Private First Class Sledge recorded in the margins of his sodden New Testament, "Mud in camp on Pavuvu was a nuisance . . . . But mud on the battlefield is misery beyond description." The 96th Division wearily reported the results of one day's efforts under these conditions: "those on forward slope slid down; those on reverse slope slid back; otherwise no change." The Marines began to chafe at the heavy-handed controls of the Tenth Army, which seemed to stall with each encounter with a fresh Japanese outpost. General Buckner favored a massive application of firepower on every obstacle before committing troops in the open. Colonel Shapley, commanding the 4th Marines, took a different view. "I'm not too sure that sometimes when they whittle you away, 10-12 men a day, then maybe it would be better to take 100 losses a day if you could get out sooner." Colonel Wilburt S. "Big Foot" Brown, a veteran artilleryman commanding the 11th Marines, and a legend in his own time, believed the Tenth Army relied too heavily on firepower. "We poured a tremendous amount of metal into those positions," he said. "It seemed nothing could be living in that churning mass where the shells were falling and roaring, but when we next advanced the Japs would still be there and madder than ever." Brown also lamented the overuse of star shells for night illumination: "I felt like we were the children of Israel in the wilderness — living under a pillar of fire by night and a cloud of smoke by day."

Such a heavy reliance on artillery support stressed the amphibious supply system. The Tenth Army's demand for heavy ordnance grew to 3,000 tons of ammo per day; each round had to be delivered over the beach and distributed along the front. This factor reduced the availability of other supplies, including rations. Front-line troops, especially the Marines, began to go hungry. Again partial succor came from the friendly skies. Marine pilots flying General Motors Avenger torpedo-bombers of VMTB-232 executed 80 air drops of rations during the first three days of June alone. This worked well, thanks to the intrepid pilots, and thanks to the rigging skills of the Air Delivery Section, veterans of the former Marine parachute battalions. Offshore from the final drive south, the ships of the fleet continued to withstand waves of kamikaze attacks. Earlier, on 17 May, Admiral Turner had declared an end to the amphibious assault phase. General Buckner thereafter reported directly to Admiral Spruance. Turner departed, leaving Vice Admiral Harry W. Hill in command of the huge amphibious force still supporting the Tenth Army. On 27 May, Admiral William F. "Bull" Halsey relieved Spruance. With that, the Fifth Fleet became the Third Fleet — same ships, same crews, different designation. Spruance and Turner began planning the next amphibious assault, the long-anticipated invasion of the Japanese home islands.

General Shepherd, appreciative of the vast amphibious resources still available on call, decided to interject tactical mobility and surprise into the sluggish campaign. In order for the 6th Marine Division to reach its intermediate objective of the Naha airfield, Shepherd first had to overwhelm the Oroku Peninsula. Shepherd could do this the hard way, attacking from the base of the peninsula and scratching seaward — or he could launch a shore-to-shore amphibious assault across the estuary to catch the defenders in their flank. "The Japanese expected us to force a crossing of the Kokuba," he said, "I wanted to surprise them." Convincing General Geiger of the wisdom of this approach was easy; getting General Buckner's approval took longer. Abruptly Buckner agreed, but gave the 6th Division barely 36 hours to plan and execute a division-level amphibious assault. Lieutenant Colonel Krulak and his G-3 staff relished the challenge. Scouts from Major Anthony "Cold Steel" Walker's 6th Reconnaissance Company stole across the estuary at night to gather intelligence on the Nishikoku Beaches and the Japanese defenders. The scouts confirmed the existence on the peninsula of a cobbled force of Imperial Japanese Navy units under an old adversary. Fittingly, this final opposed amphibious landing of the war would be launched against one of the last surviving Japanese rikusentai (Special Naval Landing Force) commanders, Rear Admiral Minoru Ota.

Admiral Ota was 54, a 1913 graduate of the Japanese Naval Academy, and a veteran of rikusentai service from as early as 1932 in Shanghai. Ten years later he commanded the 2d Combined Special Landing Force destined to assault Midway, but was thwarted by the disastrous naval defeat suffered by the Japanese. In November 1942, commanding the 8th Combined Special Landing Force in the Central Solomons, he defended Bairoko against the 1st Marine Raider Regiment. By 1945, however, the rikusentai had all but disappeared, and Ota commanded a rag tag outfit of several thousand coast defense and antiaircraft gunners, aviation mechanics, and construction specialists. Undismayed, Ota breathed fire into his disparate forces, equipped them with hundreds of machine cannons from wrecked aircraft, and made them sow thousands of mines.

Krulak and Shepherd knew they faced a worthy opponent, but also saw they held the advantage of surprise if they could act swiftly. The final details of planning centered on problems with the division's previously dependable LVTs. Sixty-five days of hard campaigning ashore had taken a heavy toll of the tracks and suspension systems of these assault amphibians. Nor were repair parts available. LVTs had served in abundance on L-Day to land four divisions; now the Marines had to scrape to produce enough for the assault elements of one regiment. Worse for the planners, the first typhoon of the season was approaching, and the Navy was getting jumpy. General Shepherd remained firm in his desire to execute the assault on K-Day, 4 June. Admiral Halsey backed him up. Shepherd considered Colonel Shapley "an outstanding officer of great ability and great leadership," and chose the 4th Marines to lead the assault. Shapley divided the 600-yard Nishikoku Beach between 2/4 on the left and 1/4 on the right. Despite heavy rains, the assault went on schedule. The Oroku Peninsula erupted in flame and smoke under the pounding of hundreds of naval guns, artillery batteries, and aerial bombs. Major Anthony's scouts seized Ono Yama island, the 4th Marines swept across the estuary, and LCMs and LCIs loaded with tanks appeared from the north, from "Loomis Harbor," named after the IIIAC Logistics Officer, Colonel Francis B. "Loopy" Loomis, Jr., a veteran Marine aviator. The amphibious force attained complete surprise. Many of 1/4's patched-up LVTs broke down enroute, causing uncomfortable delays, but enemy fire proved intermittent, and empty LVTs from the first waves quickly returned to transfer the stranded troops. The 4th Marines advanced rapidly. Soon it became time for Colonel Whaling's 29th Marines to cross. By dark on K-Day the 6th Division occupied 1,200 yards of the Oroku Peninsula. Admiral Ota furiously redirected his sailors to the threat from the rear. Then Colonel Roberts' 22d Marines began advancing along the original corridor.

The amphibious assault had been nigh letter-perfect, the typhoon came and went, and the Marines occupied the peninsula in force, capturing the airfield in two days. When the 1st Marine Division reached the south west coast north of Itoman on 7 June, Admiral Ota's force lost its chance of escape. General Shepherd then orchestrated a three-fold enveloping movement with his regiments and the outcome became inevitable. Admiral Ota was no ordinary opponent, however, and the battle for Oroku was savage and lethal. Ota's 5,000 spirited sailors fought with elan, and they were very heavily armed. No similar-sized force on Okinawa possessed so many automatic weapons or employed mines so effectively. The attacking Marines also encountered some awesome weapons at very short range — eight-inch coast defense guns redirected in land, rail-mounted eight-inch rockets (the "Screaming Mimi"), and the enormous 320mm spigot mortars which launched the terrifying "flying ashcans." On 9 June the 4th Marines reported "character of opposition unchanged; stubborn defense of high ground by 20mm and MG fire." Two days later the 29th Marines reported: "L Hill under attack from two sides; another tank shot on right flank; think an eight-inch gun." Ota could nevertheless see the end coming. On 6 June he reported to naval headquarters in Tokyo: "The troops under my command have fought gallantly, in the finest tradition of the Japanese Navy. Fierce bombardments may deform the mountains of Okinawa but cannot alter the loyal spirit of our men." Four days later Ota transmitted his final message to General Ushijima ("Enemy tank groups are now attacking our cave headquarters; the Naval Base Force is dying gloriously. . . .") and committed suicide, his duty done.

General Shepherd knew he had defeated a competent foe. He counted the costs in his after-action summary of the Oroku operation:

When the 1st Marine Division reached the coast near Itoman it represented the first time in more than a month that the division had access to the sea. This helped relieve the Old Breed's extended supply lines. "As we reached the shore we were helped a great deal by amphibian tractors that had come down the coast with supplies," said Colonel Snedeker of the 7th Marines, "Other wise we couldn't get supplies overland."

The more open country in the south gave General del Valle the opportunity to further refine the deployment of his tank-infantry teams. No unit in the Tenth Army surpassed the 1st Marine Division's synchronization of these two supporting arms. Using tactical lessons painfully learned at Peleliu, the division never allowed its tanks to range beyond direct support of the accompanying infantry and artillery forward observers. As a result, the 1st Tank Battalion was the only armored unit in the battle not to lose a tank to Japanese suicide squads — even during the swirling close quarters frays within Wana Draw. General del Valle, the consummate artilleryman, valued his attached Army 4.2-inch mortar battery. "The 4.2s were invaluable on Okinawa," he said, "and that's why my tanks had such good luck." But good luck reflected a great deal of application. "We developed the tank-infantry team to a fare-thee-well in those swales — backed up by our 4.2-inch mortars." Colonel "Big Foot" Brown of the 11th Marines took this coordination several steps further as the campaign dragged along:

Lieutenant Colonel James C. Magee's 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, used similar tactics in a bloody but successful day-long assault on Hill 69 west of Ozato on 10 June. Magee lost three tanks to Japanese artillery fire in the approach. but took the hill and held it throughout the inevitable counterattack that night. Beyond Hill 69 loomed Kunishi Ridge for the 1st Marine Division, a steep, coral escarpment which totally dominated the surrounding grass lands and rice paddies. Kunishi was much higher and longer than Sugar Loaf, equally honeycombed with enemy caves and tunnels, and while it lacked the nearby equivalents of Half Moon and Horseshoe to the rear flanks, it was amply covered from behind by Mezado Ridge 500 yards further south. Remnants of the veteran 32d Infantry Regiment infested and defended Kunishi's many hidden bunkers. These were the last of Ushijima's organized, front-line troops, and they would render Kunishi Ridge as deadly a killing ground as the Marines would ever face.

Japanese gunners readily repulsed the first tank-infantry assaults by the 7th Marines on 11 June. Colonel Snedeker looked for another way. "I came to the realization that with the losses my battalions suffered in experienced leadership we would never be able to capture (Kunishi Ridge) in daytime. I thought a night attack might be successful." Snedeker flew over the objective in an observation aircraft, formulating his plan. Night assaults by elements of the Tenth Army were extremely rare in this campaign — especially Snedeker's ambitious plan of employing two battalions. General del Valle voiced his approval. At 0330 the next morning, Lieutenant Colonel John J. Gormley's 1/7 and Lieutenant Colonel Spencer S. Berger's 2/7 departed the combat outpost line for the dark ridge. By 0500 the lead companies of both battalions swarmed over the crest, surprising several groups of Japanese calmly cooking breakfast. Then came the fight to stay on the ridge and expand the toehold. With daylight, Japanese gunners continued to pole-ax any relief columns of infantry, while those Marines clinging to the crest endured showers of grenades and mortar rounds. As General del Valle put it, "The situation was one of the tactical oddities of this peculiar warfare. We were on the ridge. The Japs were in it, on both the forward and reverse slopes."

The Marines on Kunishi critically needed reinforcements and resupplies; their growing number of wounded needed evacuation. Only the Sherman medium tank had the bulk and mobility to provide relief. The next several days marked the finest achievements of the 1st Tank Battalion, even at the loss of 21 of its Shermans to enemy fire. By removing two crewmen, the tankers could stuff six replacement riflemen inside each vehicle. Personnel exchanges once atop the hill were another matter. No one could stand erect without getting shot, so all "transactions" had to take place via the escape hatch in the bottom of the tank's hull. These scenes then became commonplace: a tank would lurch into the beleaguered Marine positions on Kunishi, remain buttoned up while the replacement troops slithered out of the escape hatch carrying ammo, rations, plasma, and water; then other Marines would crawl under, dragging their wound ed comrades on ponchos and manhandle them into the small hole. For those badly wounded who lacked this flexibility, the only option was the dubious privilege of riding back down to safety while lashed to a stretcher topside behind the turret. Tank drivers frequently sought to provide maximum protection to their exposed stretcher cases by backing down the entire 800-yard gauntlet. In this painstaking fashion the tankers managed to deliver 50 fresh troops and evacuate 35 wounded men the day following the 7th Marines' night attack. Encouraged by these results, General del Valle ordered Colonel Mason to conduct a similar night assault on the 1st Marines' sector of Kunishi Ridge. This mission went to 2/1, who accomplished it smartly the night of 13-14 June despite inadvertent lapses of illumination fire by forgetful supporting arms. Again the Japanese, furious at being surprised, swarmed out of their bunkers in counterattack. Losses mounted rapidly in Lieutenant Colonel Magee's ranks. One company lost six of its seven officers that morning. Again the 1st Tank Battalion came to the rescue, delivering reinforcements and evacuating 110 casualties by dusk. General del Valle expressed great pleasure in the success of these series of attacks. "The Japs were so damned surprised," he remarked, adding, "They used to counterattack at night all the time, but they never felt we'd have the audacity to go and do it to them." Colonel Yahara admitted during his interrogation that these unexpected night attacks were "particularly effective," catching the Japanese forces "both physically and psychologically off-guard." By 15 June the 1st Marines had been in the division line for 12 straight days and sustained 500 casualties. The 5th Marines relieved it, including an intricate night-time relief of lines by 2/5 of 2/1 on 15-16 June. The 1st Marines, back in the relative safety of division reserve, received this mindless regimental rejoinder the next day: "When not otherwise occupied you will bury Jap dead in your area." The battle for Kunishi Ridge continued. On 17 June the 5th Marines assigned K/3/5 to support 2/5 on Kunishi. Private First Class Sledge approached the embattled escarpment with dread: "Its crest looked so much like Bloody Nose that my knees nearly buckled. I felt as though I were on Peleliu and had it all to go through again." The fighting along the crest and its reverse slope took place at point-blank range — too close even for Sledge's 60mm mortars. His crew then served as stretcher bearers, extremely hazardous duty. Half his company became casualties in the next 22 hours.

Extracting wounded Marines from Kunishi remained a hair-raising feat. But the seriously wounded faced another half-day of evacuation by field ambulance over bad roads subject to interdictive fire. Then the aviators stepped in with a bright idea. Engineers cleared a rough landing strip suitable for the ubiquitous "Grasshopper" observation aircraft north of Itoman. Hospital corpsmen began delivering some of the casualties from the Kunishi and Hill 69 battles to this improbable airfield. There they were tenderly inserted into the waiting Piper Cubs and flown back to field hospitals in the rear, an eight-minute flight. This was the dawn of tactical air medevacs which would save so many lives in subsequent Asian wars. In 11 days, the dauntless pilots of Marine Observation Squadrons (VMO) -3 and -7 flew out 641 casualties from the Itoman strip. The 6th Marine Division joined the southern battlefield from its forcible seizure of the Oroku Peninsula. Colonel Roberts' 22d Marines became the fourth USMC regiment to engage in the fighting for Kunishi. The 32d Infantry Regiment died hard, but soon the combined forces of IIIAC had swept south, over lapped Mezado Ridge, and could smell the sea along the south coast. Near Ara Saki, George Company, 2/22, raised the 6th Marine Division colors on the island's southernmost point, just as they had done in April at Hedo Misaki in the farthest north. The long-neglected 2d Marine Division finally got a meaningful role for at least one of its major components in the closing weeks of the campaign. Colonel Clarence R. Wallace and his 8th Marines arrived from Saipan, initially to capture two outlying islands, Iheya Shima and Aguni Shima, to provide more early warning radar sites against the kamikazes. Wallace in fact commanded a sizable force, virtually a brigade, including the attached 2d Battalion, 10th Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Richard G. Weede) and the 2d Amphibian Tractor Battalion (Major Fenlon A. Durand). General Geiger assigned the 8th Marines to the 1st Marine Division, and by 18 June they had relieved the 7th Marines and were sweeping southeastward with vigor. Private First Class Sledge recalled their appearance on the battlefield: "We scrutinized the men of the 8th Marines with that hard professional stare of old salts sizing up another outfit. Everything we saw brought forth remarks of approval." General Buckner also took an interest in observing the first combat deployment of the 8th Marines. Months earlier he had been favorably impressed with Colonel Wallace's outfit during an inspection visit to Saipan. Buckner went to a forward observation post on 18 June, watching the 8th Marines advance along the valley floor. Japanese gunners on the opposite ridge saw the official party and opened up. Shells struck the nearby coral outcrop, driving a lethal splinter into the general's chest. He died in 10 minutes, one of the few senior U.S. officers to be killed in action throughout World War II.

As previously arranged, General Roy Geiger assumed command; his third star became effective immediately. The Tenth Army remained in capable hands. Geiger became the only Marine — and the only aviator of any service — to command a field army. The soldiers on Okinawa had no qualms about this. Senior Army echelons elsewhere did. Army General Joseph Stillwell received urgent orders to Okinawa. Five days later he relieved Geiger, but by then the battle was over. The Marines also lost a good commander on the 18th when a Japanese sniper killed Colonel Harold C. Roberts, CO of the 22d Marines, who had earned a Navy Cross serving as a Navy corpsman with Marines in World War I. General Shepherd had cautioned Roberts the previous evening about his propensity of "commanding from the front." "I told him the end is in sight," said Shepherd, "for God's sake don't expose yourself unnecessarily." Lieutenant Colonel August C. Larson took over the 22d Marines.

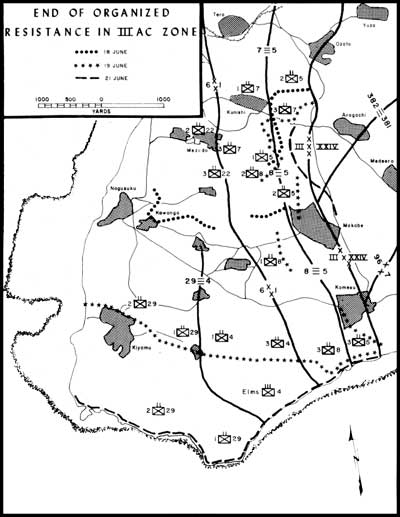

When news of Buckner's death reached the headquarters of the Thirty-second Army in its cliff-side cave near Mabuni, the staff officers rejoiced. But General Ushijima maintained silence. He had respected Buckner's distinguished military ancestry and was appreciative of the fact that both opposing commanders had once commanded their respective service academies, Ushijima at Zama, Buckner at West Point. Ushijima could also see his own end fast approaching. Indeed, the XXIV Corps' 7th and 96th Divisions were now bearing down inexorably on the Japanese command post. On 21 June Generals Ushijima and Cho ordered Colonel Yahara and others to save themselves in order "to tell the army's story to headquarters," then conducted ritual suicide.

General Geiger announced the end of organized resistance on Okinawa the same day. True to form, a final kikusui attack struck the fleet that night and sharp fighting broke out on the 22d. Undeterred, Geiger broke out the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing band and ran up the American flag at Tenth Army headquarters. The long battle had finally run its course.

|