| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

SECURING THE SURRENDER: Marines in the Occupation of Japan by Charles R. Smith At noon on 15 August 1945, people gathered near radios and hastily setup loud speakers in homes, offices, factories, and on city streets throughout Japan. Even though many felt that defeat was not far off, the vast majority expected to hear new exhortations to fight to the death or the official announcement of a declaration of war on the Soviet Union. The muted strains of the national anthem immediately followed the noon time-signal. Listeners then heard State Minister Hiroshi Shimomura announce that the next voice they would hear would be that of His Imperial Majesty the Emperor. In a solemn voice, Emperor Hirohito read the first fateful words of the Imperial Rescript:

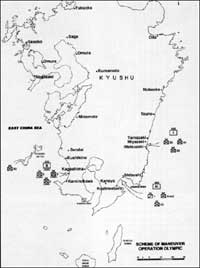

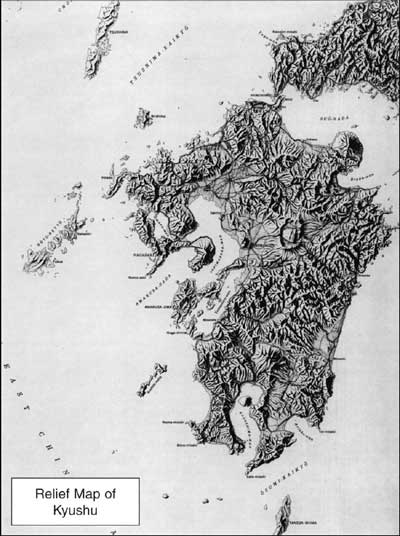

Although the word "surrender" was not mentioned and few knew of the Joint Declaration of the Allied Powers calling for unconditional surrender of Japan, they quickly understood that the Emperor was announcing the termination of hostilities on terms laid down by the enemy. After more than three and a half years of fighting and sacrifice, Japan was accepting defeat. On Guam, 1,363 nautical miles to the south, the men of the 6th Marine Division had turned in early the night before after a long day of combat training. At 2200, lights on the island suddenly came on. Radio reports had confirmed rumors circulating for days throughout the division's camp on the high ground overlooking Pago Bay: the Japanese had surrendered and there would be an immediate ceasefire. As some Marines clad only in towels or skivvies danced in the streets and members of the 22d Marines band conducted an impromptu parade, most of the 4th Marine Regimental Combat Team was on board ship, ready to leave for "occupational and possible light combat duty in Japanese - held territory." No less happy than their fellow Marines ashore, they remained cynical. The Japanese had used subterfuge before. Who could say they were not being deceptive now? In May 1945, months before the fighting ended, preliminary plans for the occupation of Japan were prepared at the headquarters of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur in Manila and Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz on Guam. Staff studies, based on the possibility of the sudden collapse or surrender of the Japanese Government and High Command, were prepared and distributed at army and fleet level for planning purposes. In early summer, as fighting still raged on Okinawa and in the Philippines, dual-planning went forward for both the subjugation of Japan by force in Operations Olympic and Coronet, and its peaceful occupation in Operations Blacklist and Campus. Many essential elements of MacArthur's Olympic and Black list plans were similar. The Sixth Army, which was slated to make the attack on the southern island of Kyushu under Olympic, was given the contingent task of occupying southern Japan under Operation Blacklist. Likewise, the Eighth Army, using the wealth of information it had accumulated regarding the island of Honshu in planning for Coronet, was designated the occupying force for northern Japan. The Tenth Army, a component of the Honshu invasion force, was given the mission of occupying Korea. Admiral Nimitz's plan envisioned the initial occupation of Tokyo Bay and other strategic areas by the Third Fleet and Marine forces, pending the arrival of formal occupation forces under General MacArthur's command. When the Japanese government made its momentous decision to surrender in the wake of atomic bombings and the Soviet Union's entry into the war, MacArthur's and Nimitz's staffs quickly shifted their focus from Operation Olympic to Blacklist and Campus, their respective plans for the occupation. In the process of coordinating the two plans, MacArthur's staff notified Nimitz's representatives that "any landing whatsoever by naval or marine elements prior to CINCAFPAC's [Mac Arthur's] personal landing is emphatically unacceptable to him." MacArthur's objections to an initial landing by naval and accompanying Marine forces was based upon his belief that they would be unable to cope with any Japanese military opposition and, more importantly, because "it would be psychologically offensive to ground and air forces of the Pacific Theater to be relegated from their proper missions at the hour of victory."

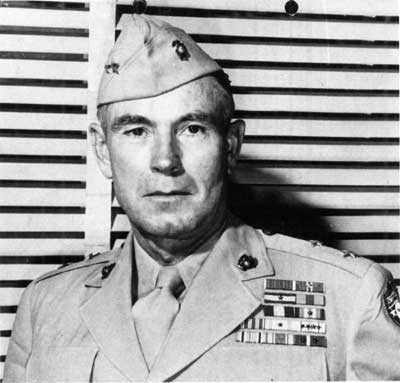

Despite apparent disagreements, MacArthur's plan for the occupation, Blacklist, was accepted. But with at least a two-week lag predicted between the surrender and a landing in force, both MacArthur and Nimitz agreed that the immediate occupation of Japan was paramount and should be given the highest priority. The only military unit available with sufficient power "to take Japan into custody at short notice and enforce the Allies' will until occupation troops arrived" was Admiral William F. Halsey's Third Fleet, then at sea 250 miles south east of Tokyo, conducting carrier air strikes against Hokkaido and northern Honshu. On 8 August, advance copies of Halsey's Operation Plan 10-45 for the occupation of Japan setting up Task Force 31 (TF 31), the Yokosuka Occupation Force, were distributed. The task force's mission, based on Nimitz's basic concept, was to clear the entrance to Tokyo Bay and anchorages, occupy and secure the Yokosuka Naval Base, seize and operate Yokosuka Airfield, support the release of Allied prisoners, demilitarize all enemy ships and defenses, and assist U.S. Army troops in preparing for the landing of additional forces. Three days later, Rear Admiral Oscar C. Badger, Commander, Battleship Division 7, was designated by Halsey to be commander, TF 31. The carriers, battleships, and cruisers of Vice Admiral John S. McCain's Task Force 38 also were alerted to organize and equip naval and Marine landing forces. At the same time, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, directed the 6th Marine Division to furnish a regimental combat team to the Third Fleet for possible occupation duty. Major General Keller E. Rockey, Commanding General, III Amphibious Corps, on the recommendation of Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., nominated Brigadier General William T. Clement, the division's assistant commander, to head the combined Fleet landing force. Brigadier General William T. Clement Leading the 4th Marines ashore at Yokosuka on 30 August was a memorable event in Brigadier General William T. Clement's life and career. Clement was 48 and had been a Marine Corps officer for 27 years at the time he was given command of the Fleet Landing Force that would make the first landing on the Japanese home islands following the nation's unconditional surrender. He was born in Lynchburg, Virginia, and graduated from Virginia Military Institute. Less than a month after reporting for active duty in 1917, Clement sailed for Haiti where he joined the 2d Marine Regiment and its operations against rebel bandits.

Upon his return to the United States in 1919, he reported for duty at Marine Barracks, Quantico, where he remained until 1923, when he became post adjutant of the Marine Detachment at the American Legation in Peking, China. In 1926, he was assigned to the 4th Marine Regiment at San Diego as adjutant and in October of the same year was given command of a company of Marines on mail guard duty in Denver, Colorado, where he remained for three months until rejoining the 4th Marines. Clement sailed with the regiment for duty in China in 1927 and was successively a company commander and regimental operations and training officer. Following his return to the United States in 1929, he became the executive officer of the Marine Recruit Depot, San Diego, and then commanding officer of the Marine Detachment on board the West Virginia. Clement spent most of the 1930s at Quantico, first as a student, then an as instructor, and finally as a battalion commander with the 5th Marines. The outbreak of World War II found Clement serving on the staff of the Commander-in-Chief, Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines. Although quartered at Corregidor, he served as a liaison among the Commandant, 16th Naval District; the Commanding General, U.S. Armed Forces in the Far East; and particularly with the forces engaged on Bataan until ordered to leave on board the U.S. submarine Snapper for Australia in April 1942. For his handling of the diversified units engaged at Cavite Navy Yard and on Bataan, he was awarded the Navy Cross. Following tours in Europe and at Quantico, Clement joined the 6th Marine Division in November 1944 as assistant division commander and took part in the Okinawa campaign. Less than two months after the Yokosuka landing, he rejoined the division in Northern China. When the division was redesignated the 3d Marine Brigade, Clement became commanding general and in June 1946 was named Commanding General, Marine Forces, Tsingtao Area. Returning to the United States in September, he was appointed President, Naval Retiring Board, and then Director, Marine Corps Reserve. In September 1949, he assumed command of Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, holding that post until his retirement in 1952. Lieutenant General Clement died in 1955. The decision of which of the division's three regiments would participate was an easy one for General Shepherd. "Without hesitation [he] selected the 4th Marines," Brigadier General Louis Metzger, Clement's former chief of staff, later wrote. "This was a symbolic gesture on his part, as the old 4th Marine Regiment had participated in the Philippine Campaign in 1942 and had been captured along with other U.S. forces in the Philippines. Now the new 4th Marines would be the main combat formation taking part in the initial landing and occupation of Japan."

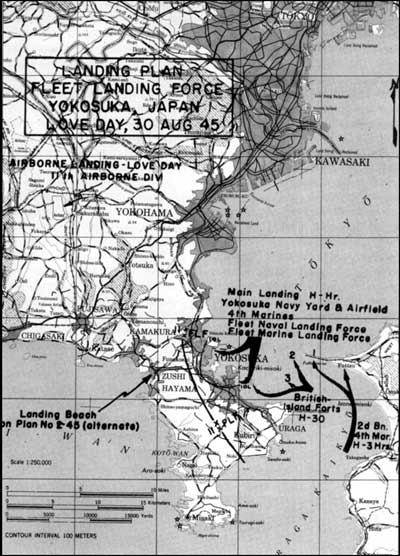

Preliminary plans for the activation of Task Force Able were prepared by III Amphibious Corps. The task force was to consist of a skeletal headquarters of 19 officers and 44 enlisted men, which was later augmented, and the 4th Marines, Reinforced, with a strength of 5,156. An amphibian tractor company and a medical company were added bringing the total task force strength up to 5,400. Officers designated to form General Clement's staff were alerted and immediately began planning to load out the task force. III Amphibious Corps issued warning orders to the division's transport quartermaster section directing that the regimental combat team, with attached units, be ready to embark 48 hours prior to the expected time of the ships' arrival. This required the complete re-outfitting of all elements of the task force which were undergoing rehabilitation following the Okinawa campaign. Requirements for clothing, ordnance, and equipment and supplies had to be determined and arranged for from the 5th Field Service Depot. Initially, this proved to be difficult due to the secret nature of the operation and that all requisitions for support from supply agencies and the Island Command on Guam had to be processed through III Amphibious Corps. At 0900 on 12 August, the veil of secrecy surrounding the proposed operation was lifted so that task force units could deal directly with all necessary service and supply agencies. All elements of the task force and the 5th Field Service Depot then went on a 24-hour work day to complete the resupply task. The regiment not only lacked supplies, but it also was understrength. Six hundred enlisted replacements were obtained from the FMFPac Transient Center, Marianas, to fill gaps in its ranks left by combat attrition and rotation to the United States. Dump areas and dock space were allotted by the Island Command to accommodate the five transports, a cargo ship, and a dock landing ship of Transport Division 60 assigned to carry Task Force Able. The mounting-out process was considerably aided by the announcement that all ships would arrive in port on 14 August, 24 hours later than originally scheduled. On the evening of the 13th, however, "all loading plans for supplies were thrown into chaos" by information that the large transport, Harris (APA 2), had been deleted from the group of ships assigned and that the Grimes (APA 172), a smaller trans port with 50 percent less capacity, would be substituted. The resultant reduction of shipping space was partially made up by the assignment of a landing ship, tank (LST) to the transport group. III Amphibious Corps informed the task force that no additional ship would be allocated. Later, after the task force departed Guam, a second LST was allotted to lift a portion of the remaining supplies and equipment, including the amphibian tractors of Company A, 4th Amphibian Tractor Battalion. On the afternoon of 14 August, loading began and continued throughout the night. The troops boarded between 1000 and 1200 the following day, and by 1600 all transports were loaded. By 1900 that evening, the transport division was ready to sail for its rendezvous at sea with the Third Fleet. Within approximately 96 hours, the regimental combat team, it was reported, "had been completely re-outfitted, all equipment deficiencies corrected, all elements provided with an initial allowance to bring them up to T/O and T/A levels, and a thirty day re-supply procured for shipment." Two days prior to the departure of the main body of Task Force Able, General Clement and the nucleus of his headquarters staff left Guam on the landing ship, vehicle Ozark (LSV 2), accompanied by the Shadwell (LSV 15) and two destroyers, to join the Third Fleet. As no definite mission had been assigned to the force, little preliminary planning had taken place so time enroute was spent studying intelligence summaries of the Tokyo area. Few maps were available and those that were proved to be inadequate. The trip to the rendezvous point was uneventful except for a reported torpedo wake across the Ozark's bow. Several depth charges were dropped by the destroyer escorts with unknown results. Halsey's ships were sighted on 18 August, and next morning, Clement and key members of his staff transferred to the battleship Missouri (BB 63) for the first of several rounds of conferences on the upcoming operation. At the conference, Task Force 31 was tentatively established and Clement learned, for the first time, that the Third Fleet Landing Force would play an active part in the occupation of Japan by landing on Miura Peninsula, 30 miles southwest of Tokyo. The primary task assigned by Admiral Halsey to Clement's forces was seizure and occupation of Yokosuka airfield and naval base in preparation for initial landings by air of the 11th Airborne Division. Located south of Yokohama, 22 miles from Tokyo, the sprawling base contained two airfields, a seaplane base, aeronautical research center, optical laboratory, gun factory and ordnance depot, torpedo factory, munitions and aircraft storage, tank farms, supply depot, ship yard, and training schools and hospitals. During the war approximately 70,000 civilians and 50,000 naval ratings worked or trained at the base. Collateral missions included the demilitarization of the entire Miura Peninsula, which formed the western arm of the headlands enclosing Tokyo Bay, and the seizure of the Zushi area, including Hayama Imperial Palace, General MacArthur's tentative headquarters, on the southwest coast of the peninsula. Two alternative schemes of maneuver were proposed to accomplish these missions. The first contemplated a landing by assault troops on the beaches near Zushi, followed by a five-mile drive east across the peninsula in two columns over the two good roads to secure the naval base for the landing of supplies and reinforcements. The second plan involved simultaneous landings from within Tokyo Bay on the beaches and docks of Yokosuka naval base and air station, to be followed by the occupation of the Zushi area, thus sealing off and then demilitarizing the entire peninsula. The Zushi landing plan was preferred since it did not involve bringing ships into the restricted waters south of Tokyo Bay until assault troops had dealt with "the possibility of Japanese treachery." Following the conference, Admiral Halsey recommended to Lieutenant General Robert L. Fichelberger, commander of the Eighth Army, whom MacArthur had appointed to command forces ashore in the occupation of northern Japan, that the Zushi plan be adopted. At 1400 on 19 August, Task Force 31 was officially organized and Admiral Badger formed the ships assigned to the force into a separate tactical group, the transports and large amphibious ships in column, with circular screens composed of destroyers and high speed transports. In addition, three subordinate task units were formed: Third Fleet Marine Landing Force; Third Fleet Naval Landing Force; and a landing force of sailors and Royal Marines from Vice Admiral Sir Bernard Rawling's British Carrier Task Force. To facilitate organization and establish control over the three provisional commands, the transfer of American and British sailors and Marines and their equipment to designated transports by means of breeches buoys and cargo slings began immediately. Carriers, battleships, and cruisers were brought along both sides of a transport to expedite the operation. In addition to the landing battalions of sailors and Marines, fleet units formed base maintenance companies, a naval air activities organization to operate Yokosuka airfield, and nucleus crews to seize and secure Japanese vessels. In less than three days, the task of transferring at sea some 3,500 men and hundreds of tons of weapons, equipment, and ammunition was accomplished without accident. As soon as they reported on board their transports, the newly organized units began an intensive program of training for ground combat operations and occupation duties.

On 20 August, the ships carrying the 4th Marine Regimental Combat Team joined the burgeoning task force and General Clement and his staff transferred from the Ozark to the Grimes. Clement's command now included the 5,400 men of the reinforced 4th Marines; a three-battalion regiment of approximately 2,000 Marines from the ships of Task Force 38; 1,000 sailors from Task Force 38 organized into two landing battalions; a battalion of nucleus crews for captured shipping; and a British battalion of 200 sea men and 250 Royal Marines. To act as a floating reserve, five additional battalions of partially equipped sailors were organized from within Admiral McCain's carrier battle group. The next day, General Fichelberger, who had been informed of the alternative plans formulated by Admirals Halsey and Badger, directed that the landing be made at the naval base rather than in the Zushi area. Although there was mounting evidence that the enemy would cooperate fully with the occupying forces, the Zushi area, Fichelberger pointed out, had been selected by MacArthur as his headquarters area and was therefore restricted. His primary reason, however, for selecting Yokosuka rather than Zushi as the landing site involved the overland movement of the landing force. "This overland movement [from Zushi to Yokosuka]," Brigadier General Metzger later noted, "would have exposed the landing force to possible enemy attack while its movement was restricted over narrow roads and through a series of tunnels which were easily susceptible to sabotage. Further, it would have delayed the early seizure of the major Japanese naval base." Fichelberger's dispatch also included information that the 11th Airborne Division would make its initial landing at Atsugi airfield, a few miles northwest of the northern end of the Miura Peninsula, instead of at Yokosuka. The original plans, which were prepared on the assumption that General Clement's men would seize Yokosuka airfield for the airborne operation, had to be changed to provide for a simultaneous Army-Navy landing. A tentative area of responsibility, including the cities of Uraga, Kubiri, Yokosuka, and Funakoshi, was assigned to Clement's force. The remainder of the peninsula was assigned to Major General Joseph M. Swing's 11th Airborne Division. While Fichelberger's directive affected the employment of the Fleet Landing Force it did not place the force under Eighth Army control.

To insure the safety of allied warships entering Tokyo Bay, Clement's operation plan detailed the British Landing Force to occupy and demilitarize three small island forts in the Uraga Strait at the entrance to Tokyo Bay. To erase the threat of shore batteries and coastal forts, the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines, supported by an underwater demolition team and a team of 10 Navy gunner's mates to demilitarize the heavy coastal defense guns, was given the mission of landing on Futtsu Saki, a long, narrow peninsula which jutted from the eastern shore into Uraga Strait at the mouth of Tokyo Bay. After completing its mission, the battalion was to reembark in its landing craft to take part in the main landing as the regiment's reserve battalion. Nucleus crews from the Fleet Naval Landing Force were to enter Yokosuka's inner harbor prior to H-Hour and take possession of the damaged battleship Nagato, whose guns commanded the landing beaches. The 4th Marines, with the 1st and 3d Battalions in assault, was scheduled to make the initial landing at Yokosuka on L-Day. The battalions of the Fleet Marine and Naval Landing Forces were to land in reserve and take control of specific areas of the naval base and airfield, while the 4th Marines pushed inland to link up with elements of the 11th Airborne Division landing at Atsugi airfield. The cruiser San Diego (CL 53), Admiral Badger's flagship; 4 destroyers; and 12 assault craft were to be prepared to furnish naval gunfire support on call. Four observation planes were assigned to observe the landing, and although there were to be no combat planes in direct support, more than 1,000 carrier-based planes would be armed and available if needed. Though it was hoped that the Yokosuka landing would be uneventful, Task Force 31 was prepared to deal with either organized resistance or individual fanaticism on the part of the Japanese. L-Day was originally scheduled for 26 August, but on the 20th, storm warnings indicating that a typhoon was developing 300 miles to the southeast forced Admiral Halsey to postpone the landing date to the 28th. Ships were to enter Sagami Wan, the vast outer bay which led to Tokyo Bay, on L minus 2 day. To avoid the typhoon, all task forces were ordered to proceed southwest toward a "temporary point" off Sofu-gan, where they were replenished and refueled. On 25 August, word was received from General MacArthur that the typhoon danger would delay Army air operations for 48 hours, and L-Day was consequently set for 30 August, with the Third Fleet entry into Sagami Wan on the 28th.

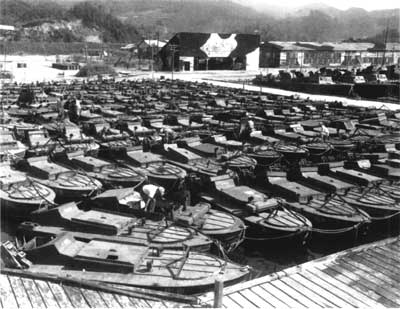

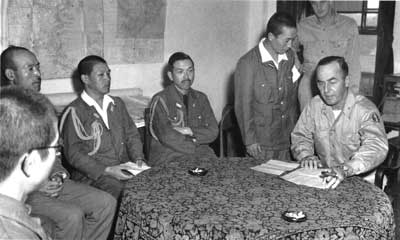

The Japanese had been instructed as early as 15 August to begin minesweeping in the waters off Tokyo to facilitate the operations of the Third Fleet. On the morning of the entrance into Sagami Wan, Japanese emissaries and pilots were to meet with Rear Admiral Robert B. Carney, Halsey's Chief of Staff, and Admiral Badger on board the Missouri to receive instructions relative to the surrender of the Yokosuka Naval Base and to guide the first allied ships into anchorages. Halsey was not anxious to keep his ships, many of them small vessels crowded with troops, at sea in typhoon weather, and he asked and received permission from MacArthur to put into Sagami Wan one day early. Early on the 27th, the Japanese emissaries reported on board the Missouri. Several demands were presented, most of which centered upon obtaining information relative to minefields and shipping channels. Japanese pilots and interpreters were then put on board a destroyer and delivered to the lead ships of Task Force 31. Due to a lack of suitable minesweepers which had prevented the Japanese from clearing Sagami Wan and Tokyo Bay, the channel into Tokyo Bay was immediately check-swept with negative results. By late afternoon, the movement of Admiral Badger's task force to safe anchorages in Sagami Wan was accomplished without incident. At 0900 on 28 August, the first American task force, consisting of the combat elements of Task Force 31, entered Tokyo Bay and dropped anchor off Yokosuka at 1300. During the movement, Naval Task Forces 35 and 37 stood by to provide fire support if needed. Carrier planes of Task Force 38 conducted an air demonstration in such force "as to discourage any treachery on the part of the enemy." In addition, combat air patrols, direct support aircraft, and planes patrolling outlying airfields flew low over populated areas to reinforce the allied presence. Shortly after anchoring, Vice Admiral Michitore Totsuka, Commandant of the First Naval District and Yokosuka Naval Base, and his staff reported to Admiral Badger in the San Diego for further instructions regarding the surrender of his command. They were informed that the naval base area was to be cleared of all personnel except for skeletal maintenance and guard crews; guns of the forts, ships, and coastal batteries commanding the bay were to be rendered inoperative; the breech blocks were to be removed from all antiaircraft and dual-purpose guns and their positions marked with white flags visible four miles to seaward; and, Japanese guides and interpreters were to be on the beach to meet the landing force. Additionally, guards were to stationed at each warehouse and building with a complete inventory on its contents and appropriate keys.

As the naval commanders made arrangements for the Yokosuka landing, a reconnaissance party of Army Air Force technicians with emergency communications and airfield engineer equipment landed at Atsugi airfield to prepare the way for the airborne operation on L-Day. Radio contact was established with Okinawa where the 11th Division was waiting to execute its part in Blacklist. The attitude of the Japanese officials, both at Yokosuka and Atsugi, was uniformly one of outward subservience and docility. But years of bitter experiences caused many allied commanders and troops to view the emerging picture of the Japanese as meek and harmless with a jaundiced eye. As Admiral Carney noted at the time: "It must be remembered that these are the same Japanese whose treachery, cruelty, and subtlety brought about this war; we must be continually vigilant for overt treachery. . . They are always dangerous." During the Third Fleet's first night at anchor, there was a fresh reminder of Japanese brutality. Two British prisoners of war hailed one of the fleet's picket boats in Sagami Wan and were taken on board the San Juan (CL 54), command ship of the specially constituted Allied Prisoner of War Rescue Group. Their description of life in the prison camps and of the extremely poor physical condition of many of the prisoners, later confirmed by an International Red Cross representative, prompted Halsey to order the rescue group into Tokyo Bay and to stand by for action on short notice. At 1420 on the 29th, Admiral Nimitz arrived by seaplane from Guam and authorized Halsey to begin rescue operations immediately, although MacArthur had directed the Navy not begin recovery operations until the Army was ready. Special teams, guided by carrier planes overhead, quickly began the task of bringing in allied prisoners from the Omori and Ofuna camps and the Shanagama hospital. By 1910 that evening, the first prisoners of war arrived on board the hospital ship Benevolence (AH 13), and at midnight 739 men had been brought out. After evacuating camps in the Tokyo area, the San Juan moved south to the Nagoya Hamamatsu area and then north to the Sendai-Kamaishi area. During the next 14 days, more than 19,000 allied prisoners were liberated.

Also that evening, for the first time since Pearl Harbor, the ships of the Third Fleet were illuminated. As General Metzger later remembered: "Word was passed to illuminate ship, but owing to the long wartime habit of always darkening ship at night, no ship would take the initiative in turning their lights on. Finally, after the order had been repeated a couple of times lights went on. It was a wonderful picture with all the ships flying large battle flags both at the foretruck and the stern. In the background was snowcapped Mount Fuji." Movies were shown on the weather decks. While the apprehension of some lessened, lookouts were still posted, radars continued to search, and the ships remained on alert. Long before dawn on L-Day, three groups of Task Force 31 transports, with escorts, moved from Sagami Wan into Tokyo Bay. The first group of transports carried the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines; the second the bulk of the landing force, consisting of the rest of the 4th Marines and the Fleet Marine and Naval Landing Forces; and the third, the British Landing Force. All plans of the Yokosuka Occupation Force had been based on an H-Hour for the main landing of 1000, but last-minute word was received from General MacArthur on the 29th that the first transport planes carrying the 11th Airborne Division would be landing at Atsugi airfield at 0600. To preserve the value and impact of simultaneous Army-Navy operations, Task Force 31's plans were changed to allow for the earlier landing time. As their landing craft approached the beaches of Futtsu Saki, the Marines of 2d Battalion, 4th Marines spotted a sign left on shore by their support team: "US NAVY UNDERWATER DEMOLITION TEAMS WELCOME MARINES TO JAPAN." At 0558, the ramps dropped and Company G, under First Lieutenant George B. Lamberson, moved ashore. While Lamberson's company and another seized the main fort and armory, a third landed on the tip of the peninsula and occupied the second fort. The Japanese, they found, had followed their instructions to the letter. The German made coastal and antiaircraft guns had been rendered useless and only a 22-man garrison remained to oversee the peaceful turnover. As the Japanese soldiers marched away, the Marines, as Staff Sergeant Edward Meagher later reported, "began smashing up the rifles, machine guns, bayonets and antiaircraft guns. They made a fearful noise doing it. Quite obviously, they hadn't enjoyed doing anything so much in a long, long time." By 0845, after raising the American flag over both forts, the battalion, its mission accomplished, reembarked for the Yokosuka landing, scheduled for 0930. With the taking of the Futtsu Saki forts and the landing of the first transports at Atsugi, the occupation of Japan was underway. With first light came dramatic evidence that the Japanese would comply with the surrender terms. Lookouts on board Task Force 31 ships could see white flags flying over abandoned and inoperative gun positions. A 98-man nucleus crew from the battleship South Dakota (BB 57) boarded the battle ship Nagato at 0805 and received the surrender from a skeleton force of officers and technicians; the firing locks of the ship's main battery had been removed and all secondary and antiaircraft guns relocated to the Navy Yard. "At no time was any antagonism, resentment, arrogance or passive resistance encountered; both officers (including the captain) and men displaying a very meek and subservient attitude," noted Navy Captain Thomas J. Flynn in his official report. "It seemed almost incredible that these bowing, scraping, and scared men were the same brutal, sadistic enemies who had tortured our prisoners, reports of whose plight were being received the same day." The morning was warm and bright. There was hardly a ripple on the water as the 4th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Fred D. Beans, scrambled into landing craft. Once on board, they adjusted their heavy packs and joked and laughed as the coxswains powered the craft toward the rendezvous point a few miles off shore. Officers and senior enlisted men reminded their marines of orders given days before: weapons would be locked and not used unless fired upon; insulting epithets in connection with the Japanese as a race or individuals would not be condoned; and all personnel were to present a smart military bearing and proper deportment. "When you hit the beach, Navy cameramen who will land earlier will be there," Lieutenant Colonel George B. Bell said to the men of the 1st Battalion. "They will be taking pictures. Pictures of you men landing. I don't want any of you mugging the lenses. Simply get ashore as quickly as possible and do your job." As the Marines of 1st Battalion and 3d Battalion gave their gear a last minute check, the coxswain in the lead craft signaled with both hands aloft and the boats, now abreast, moved toward the shore exactly on schedule. Out of habit, the Marines crouched low in the boat. "No one knew what would happen on the beach. You couldn't be absolutely certain. You were dealing with the Nip." Accompanying the Marines were "enough correspondents, photographers and radio men," one Marine observed, "to make up a full infantry company." At 0930, Marines of Lieutenant Colonel Bell's 1st Battalion landed on Red Beach southeast of Yokosuka airfield and those of the 3d Battalion, led by Major Wilson B. Hunt, on Green Beach in the heart of the Navy Yard. There was no resistance. The few unarmed Japanese present wore white arm bands, as instructed, to signify that they were essential maintenance troops, officials, or interpreters. Hot-heads and others considered unable to abide by the Emperor's decree had been removed. Oriented by the few remaining personnel, the two Marine battalions rapidly moved forward, fanning out around hangers and buildings. Leaving guards at warehouses and other primary installations, the Marines moved across the airfield and through the Navy Yard, checking all buildings and each gun position to insure that the breechblock had been removed and "driving all non-essential Japanese before them." With the seizure of Yokosuka, the three island forts in Surago Channel, and the landing on Azuma Peninsula by British forces, the initial phase of the occupation was completed.

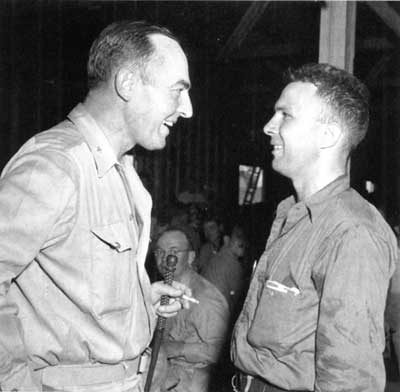

General Clement and his staff landed at 1000 on Green Beach where they were met by Japanese Navy Captain Kiyoshi Masuda and his staff who formally surrendered the naval base. "They were informed that non-cooperation or opposition of any kind would be severely dealt with." Clement then proceeded to the Japanese headquarters building where an American flag was raised with appropriate ceremony at 1015. The flag used was the same raised by the First Provisional Brigade on Guam's Orote Peninsula and by the 6th Marine Division on Okinawa. Vice Admiral Michitore Totsuka had been ordered to be present on the docks of the naval base to surrender the First Naval District to Admiral Carney, acting for Admiral Halsey, and Admiral Badger. At 1030, the San Diego, with Carney and Badger on board, tied up at the dock at Yokosuka. With appropriate ceremony, the formal surrender took place at 1045, after which Badger, accompanied by Clement, departed for the former naval base headquarters building, the designated site for Task Force 31 and Fleet Landing Force headquarters. At noon, with operations proceeding satisfactorily at Yokosuka and in the occupation zone of the 11th Airborne Division, General Eichelberger assumed operational control of the Fleet Landing Force from Halsey. Both of the top American commanders in the Allied drive across the Pacific set foot on Japanese soil on L-Day. General MacArthur landed at Atsugi airfield and subsequently set up temporary headquarters in Yokohama's Grand Hotel, one of the few buildings in the city to escape serious damage. Admiral Nimitz, accompanied by Halsey, came ashore at Yokosuka at 1330 to make an inspection of the naval base. Reserves and reinforcements landed at Yokosuka during the morning and early afternoon according to schedule. The Fleet Naval Landing Force took over the Navy Yard area secured by 3d Battalion, and the Fleet Marine Landing Force occupied the airfield installations seized by 1st Battalion. The British Landing Force, after evacuating all Japanese personnel from the island forts, landed at the navigation school in the naval base and took over the area between the sectors occupied by the Fleet Naval and Marine Landing Forces. Azuma Peninsula, a large hill mass extensively tunneled as a small boat supply base, which was part of the British occupation area, was investigated by a force of Royal Marines and found abandoned.

Relieved by the other elements of the landing force, the 4th Marines moved out to the Initial Occupation Line and set up a perimeter defense for the naval base and airfield. There they met groups of uniformed police brought down from Tokyo ostensibly to separate the occupational forces from the local Japanese population. Later, patrol contact was made with the 11th Airborne Division, which had landed 4,200 men during the day. The first night ashore was quiet. Guards were posted at major installations while small roving patrols covered the larger areas on which no guards were posted. A beer ration was issued to those not on duty. "We got a couple of trucks and went up to Yokohama," Lieutenant Colonel Beans noted later, "and brought two truckloads of beer back at night, which we paid for in cash. We had no trouble whatever . . . because the entire Navy Yard had been cleared." The 4th Marines had carried out General MacArthur's orders to disarm and demobilize with amazing speed. There was no evidence that the Japanese would do anything but cooperate. It was clear, for the moment, that the occupation would succeed.

On 31 August, Clement's forces continued to consolidate their hold on the naval base and the surrounding defense area. On orders from General Eichelberger, Company L, 3d Battalion, sailed in two destroyer transports to Tateyama Naval Air Station on the northeastern shore of Sagami Wan to accept its surrender and to reconnoiter the beach approaches and cover the 3 September landing of the Army's 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team. With the complete cooperation of the Japanese Army, Navy, and Foreign Office, the company quickly reconnoitered the beaches and then set up its headquarters at the air station. Likewise, elements of 1st Battalion, 15th Marines, under Lieutenant Colonel Walter S. Osipoff, moved south to accept the surrender and demilitarize Japanese garrisons in the Uraga Kurihama area. Less than 500 yards from where Commodore Matthew Perry and his Marine detachment landed 92 years earlier, Osipoff, in a simple ceremony, took control of the Kurihama Naval Base. Japanese officials turned over complete inventories of all equipment and detailed maps of defensive installations, including guns so carefully camouflaged that it would have taken Marine patrols weeks to find them. Here, as at Tateyama, the Japanese carried out the surrender instructions without resistance. As Lieutenant Colonel Osipoff noted:

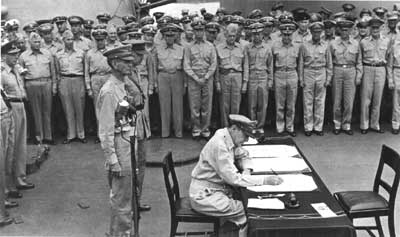

Occupation operations continued to run smoothly as preparations were made to accept the formal surrender of the Japanese Empire on board the Missouri, where leading Allied commanders had gathered from every corner of the Pacific. At 0930 on 2 September, under the flag that Commodore Perry had flown in Tokyo Bay, the Japanese representative of the Emperor, Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, and of the Imperial General Staff, General Yoshijiro Umezu, signed the surrender documents. General MacArthur then signed as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) and Admiral Nimitz for the United States. They were followed in turn by other senior allied representatives. The war that began at Pearl Harbor now officially was ended and the occupation begun. When later asked how many troops would be needed to occupy Japan, MacArthur said that 200,000 would be adequate. Lieutenant General Roy S. Geiger, Commanding General, FMFPac, agreed. "Sure," he said, "that'll be enough. There's no fight left in the Japs." Then he added: "Why, a squad of Marines could handle the whole affair." As the surrender ceremony took place on the main deck of the Missouri, advance elements of the Eighth Army's occupation force entered Tokyo Bay. Ships carrying the Headquarters of the XI Corps and the 1st Cavalry Division docked at Yokohama. Transports with the 112th Cavalry on board moved to Tateyama, and on 3 September the troopers landed and relieved Company L, 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, which then returned to Yokosuka. With the occupation proceeding smoothly, plans were made to dissolve the Fleet Landing Force and Task Force 31. The 4th Marines was selected to assumed responsibility for the entire naval base area and airfield. The first unit to return to the fleet was the British Landing Force, which was relieved by the 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, of the area between the Navy Yard and the airfield on 4 September. The Fleet Marine Landing Force was then relieved of its control in the Torpedo School, followed by the relief of the Fleet Naval Landing Force in the eastern end of the Navy Yard by the 3d Battalion. By 6 September, the 1st Battalion had relieved the remaining elements of the Fleet Marine Landing Force of the airfield and all ships' detachments of sailors and Marines had returned to their parent vessels and the provisional landing units deactivated.

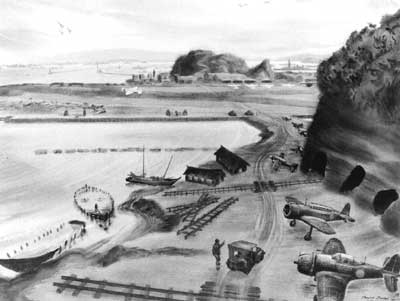

While a large part of the strength of the Fleet Landing Force was returning to normal duties, a considerable augmentation to Marine strength in northern Honshu was being made. On 23 August, AirFMFPac had designated Marine Aircraft Group 31 (MAG-31), then at Chimu airfield on Okinawa, to move to Japan as a supporting air group for the northern occupation. Colonel John C. Munn, the group's commanding officer, reconnoitered Yokosuka airfield and its facilities soon after the initial landing and directed necessary repairs to runways and taxiways in addition to assigning areas to each unit of the group. On 7 September, the group headquarters, operations, intelligence, and the 24 F4U Corsairs and men of Marine Fighter Squadron 441 flew in from Okinawa. The group was joined by Marine Fighter Squadron 224 on the 8th; Marine Fighter Squadron 311 on the 9th; Marine Night Fighter Squadron 542 on the 10th; and Marine Torpedo Bomber Squadron 131 on the 12th. "The entire base," the group reported, "was found [to be in] extremely poor police and all structures and living quarters in a bad state of repair. All living quarters were policed . . . under the supervision of the medical department, prior to occupation." As additional squadrons arrived, the air base was transformed. Complete recreational facilities were established, consisting of a post exchange, theater, basketball courts, and enlisted recreation rooms in each of the squadron's barracks.

When not engaged in renovating the air base or on air missions, liberty parties were organized and sent by boat to Tokyo. Preference was given to personnel who were expected to return to the United States for discharge. Fraternzation, although originally forbidden by the American high command, was allowed after the first week. "The Japanese Geisha girls have taken a large share of the attention of the many curious sight-seers of the squadron," reported Major Michael R. Yunck, commanding officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 311. "The Oriental way of life is something very hard for an American to comprehend. The opinions on how the occupation job 'should be done' range from the most generous to the most drastic — all agreeing on one thing, though, that it is a very interesting experience." Prostitution and the resultant widespread incidence of venereal diseases were ages old in Japan. "The world's oldest profession" was legal and controlled by the Japanese government; licensed prostitutes were confined to restricted sections. Placing these sections out of bounds to American forces did not solve the problem of venereal exposure, for, as in all ports such as Yokosuka, clandestine prostitution continued to flourish. In an attempt to prevent uncontrolled exposure, all waterfront and backstreet houses of prostitution were placed out of bounds. A prophylaxis station was established at the entrance to a Japanese police-controlled "Yashuura House" (a house of prostitution exclusively for the use of occupation forces), another in the center of the Yokosuka liberty zone, and a third at the fleet landing. These stations were manned by hospital corpsmen under the supervision of a full-time venereal disease-prevention medical officer. In addition, a continuous educational campaign was carried out urging continence and warning of the dangerous diseased condition of prostitutes. These procedures resulted in a drastic decline in reported cases of diseases originating in the Yokosuka area.

On 8 September, the group's Corsairs and Hellcats, stripped of about two and a half tons of combat weight, began surveillance flights over the Tokyo Bay area and the Kanto Plain north of the capital. The purpose of the missions was to observe and report any unusual activity by Japanese military forces and to survey all airfields in the area. Initially, Munn's planes served under Third Fleet command, but on the 16th, operational control of MAG-31 was transferred to the Fifth Air Force. A month later, the group was returned to Navy control and reconnaissance flights in the Tokyo area and Kanto Plain discontinued. Operations of the air group were confined largely to mail, courier, transport, and training flights to include navigation, tactics, dummy gunnery, and ground control approach practice. By mid-October, the physical condition of the base had been improved to such an extent that the facilities were adequate to accommodate the remainder of the group's personnel. On 7 December, the group's four tactical squadrons were placed under the operational control of the Far Eastern Air Force and surveillance and reconnaissance flights again resumed. On 8 September, Admiral Badger's Task Force 31 was dissolved and the Commander, Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, assumed responsibility for the naval occupation area. General Clement's command, again designated Task Force Able, continued to function for a short time thereafter while most of the reinforcing units of the 4th Marines loaded out for return to Guam. On the 20th, Lieutenant Colonel Beans relieved General Clement of his responsibilities at Yokosuka, and the general and his staff flew back to Guam to rejoin the 6th Division. Before he left, Clement was able to take part in a ceremony honoring more than 120 officers and men of the "Old" 4th Marines, captured on Bataan and Corregidor.

After the initial major contribution of naval land forces to the occupation of northern Japan, the operation became more and more an Army task. As additional troops arrived, the Eighth Army's area of effective control grew to encompass all of northern Japan. In October, the occupation zone of the 4th Marines was reduced to include only the naval base, airfield, and town of Yokosuka. In effect, the regiment became a naval base guard detachment, and on 1 November, control of the 4th Marines passed from Eighth Army to the Commander, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka. While the Marine presence gradually diminished, activity in the surrounding area began to return to normal. Japanese civilians started returning to the city of Yokosuka in large numbers. "The almost universal attitude was at first one of timidity and fear, then curiosity," it was reported. "Banks opened and started to operate . . . . Post offices and telegraph offices started to function smoothly, and movie houses began to fill with civilian crowds." Unlike Tokyo and Yokohama, the Yokosuka area had escaped much destruction and was remarkably intact. On base, evacuated Japanese barracks were quickly cleaned up and made reasonably liveable. The Japanese furnished cooks, mess boys, and housekeeping help, allowing Marines more time to explore the rice-paddy and beach resort-dotted countryside, and liberty in town. Allowed only five hours liberty three times a week, most enlisted Marines saw little of Japan, except for short sight-seeing tours to Tokyo or Kamakura. Yokosuka, a small city with long beer lines, quickly lost its novelty and Yokohama was off limits to enlisted personnel. So most Marines would "have a few brews and head back for the base at 4 p.m. when the beer sales cease." Their behavior was remarkable considering only a few months before they had fought a hard and bloody battle on Okinawa. Crimes against the local Japanese population were few and, for the most part, petty. It was the replacement, not the combat veteran, who, after a few beers, would "slug a Jap" or curse them to their faces. Of the few problems, two stood out — rape and the black market. Japanese women, so subdued, if propositioned would comply and later charge "rape." "Our courts gave severe sentences, which I approved," noted one senior commander. "This satisfied the Japanese honor. I expected the sentences to be greatly reduced, as they were, in the United States. The sooner these men were returned home, the better for all hands, including the Japanese." In addition, the utter lack and concomitant demand for consumer goods caused some Marines to smuggle items, such as cigarettes, out to the civilian market where they brought a high price. Although attempts were made to curb the practice, many unnecessary and expensive courts-martial where held "which branded our men with bad conduct discharges."

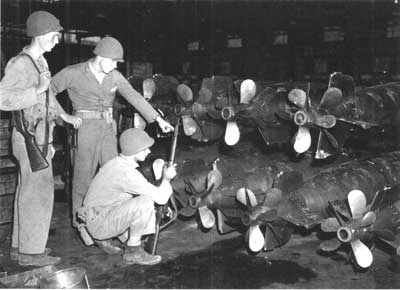

In addition to routine duties and security and military police patrols, the Marines also carried out Eighth Army demilitarization directives, collecting and disposing of Japanese military and naval materiel. In addition, they searched their area of responsibility for caches of gold, silver, and platinum. During the search, no official naval records, other than inventories and a few maps and charts, were found. It was later learned that the Japanese had been ordered to burn or destroy all documents of military value to the Allies. The surrender of all garrisons having been taken, motorized patrols with truck convoys were sent out to collect as many small arms, weapons, and as much ammunition as possible. The large amount of such supplies in the Yokosuka area made the task an extensive one. In addition, weekly patrols from the regiment supervised the unloading at Uraga of Japanese troops and civilians returning from such by passed Pacific outposts as Wake, Yap, and Truk. Although there was concern that some Japanese soldiers might cause trouble, none did. On 20 November, the 4th Marines was removed from the administrative control of the 6th Division and placed directly under FMFPac. Orders were received directing that preparations be made for 3d Battalion to relieve the regiment of its duties in Japan, effective 31 December. In common with the rest of the Armed Forces, the Marine Corps faced great public and Congressional pressure to send its men home for discharge as rapidly as possible. The Corps' world-wide commitments had to be examined with this in mind. The Japanese attitude of cooperation with occupation authorities fortunately permitted considerable reduction of troop strength. In Yokosuka, Marines who did not meet the age, service, or dependency point totals necessary for discharge in December or January were transferred to the 3d Battalion, while men with the requisite number of points were concentrated in the 1st and 2d Battalions.

On 1 December, the 1st Battalion completed embarkation on board the carrier Lexington (CV 16) and sailed for the West Coast to be disbanded. On the 24th, the 3d Battalion, reinforced by regimental units and a casual company formed to provide replacements for Fifth Fleet Marine detachments, relieved 2d Battalion of all guard responsibilities. The 2d Battalion, with Regimental Weapons and Headquarters and Service Companies, began loading out operations on the 27th and sailed for the United States on board the attack cargo ship Lumen (AKA 30) on New Year's Day. Like the 1st, the 2d Battalion and the accompanying two units would be disbanded. All received war trophies: Japanese rifles and bayonets were issued to enlisted men; officers received swords less than 100 years old; pistols were not issued and field glasses were restricted to general officers. At midnight on 31 December, Lieutenant Colonel Bruno A. Hochmuth, the regiment's executive officer, took command of the 3d Battalion, as the battalion assumed responsibility for the security of the Naval Station, Marine Air Base, and the city of Yokosuka. A token regimental headquarters remained behind to carry on the name of the 4th Marines. Six days later, the headquarters detachment left Japan to rejoin the 6th Marine Division then in Tsingtao, China. On 15 February, the 3d Battalion was redesignated the 2d Separate Guard Battalion (Provisional), Fleet Marine Force, Pacific. An internal reorganization was carried out and the battalion was broken down into guard companies. Its military police and security duties in the naval base area and city of Yokosuka remained the same. The major task of demilitarization in the naval base having been completed, the battalion settled into a routine of guard duty, ceremonies, and training, little different from that of any Navy yard barracks detachment in the United States.

In January, the Submarine Base was returned to Japanese control. With the return of the Torpedo School-Supply Base Area, the relief of all gate posts by naval guards, and the detachment of more than 300 officers and men in March, the 2d and 4th Guard Companies were disbanded and the security detail drawn from a consolidated 1st Guard Company. On 1 April, MAG-31 relieved the 3d Guard Company of security responsibility for the Air Base and the company was disbanded. With additional drafts of personnel for discharge or reassignment and an order to reduce the Marine strength to 100, the Commander, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, responded. "I reacted," Captain Benton W. Decker later wrote, "reporting that the security of the base would be jeopardized and that 400 Marines were necessary, whereupon the order was canceled, and a colonel was ordered to relieve Lieutenant Colonel Bruno Hochmuth. Again, I insisted that Lieutenant Colonel Hochmuth was capable of commanding my Marine unit to my complete satisfaction, so again, Washington canceled an order." On 15 June, the battalion, reduced in strength to 24 officers and 400 men, was redesignated Marine Detachment, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, Lieutenant Colonel Hochmuth commanding. The Senior Marine Commanders The three senior Marine commanders on Kyushu were seasoned combat veterans and well versed in combined operations — qualities that enhanced Marine Corps contributions to the complex occupation duties and relations with the U.S. Sixth Army. Major General Harry Schmidt commanded V Amphibious Corps. Schmidt was 59, a native of Holdrege, Nebraska, and a graduate of Nebraska State Normal College. He was commissioned in 1909 and in 1911 reported to Marine Barracks, Guam. Following a series of short tours in the Philippines and at state-side posts, he spent most of World War I on board ship. Interwar assignments included Quantico, Nicaragua, Headquarters Marine Corps, and China, where he served as Chief of Staff of the 2d Marine Brigade. Returning to Headquarters in 1938, Schmidt first served with the Paymaster's Department and then as assistant to the Commandant. In 1943, he assumed command of the 4th Marine Division which he led during the Roi Namur and Saipan Campaigns. Given the command of the V Amphibious Corps a year later, he led the unit during the assault and capture of Tinian and Iwo Jima. For his accomplishment during the campaigns, Schmidt received three Distinguished Service Medals. Ordered back to the United States following occupational duties in Japan, he assumed command of the Marine Training and Replacement Command, San Diego. General Schmidt died in 1968.

Major General LeRoy P. Hunt commanded the 2d Marine Division. Hunt was 53, a native of Newark, New Jersey, and a graduate of the University of California. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1917 and served with great distinction with the 5th Marines during World War I, receiving the Navy Cross and Distinguished Service Cross for repeated acts of heroism. Postwar assignments were varied, ranging from sea duty to commanding officer of the Western Mail Guard Detachment and work with the Work Projects Administration's Matanuska Colonization venture in Alaska. Following a short tour in Iceland, he was given command of the 5th Marines which he led in the seizure and defense of Guadalcanal. As the 2d Marine Division's assistant division commander he participated in mopping-up operations on Saipan and Tinian and in the Okinawa Campaign. Appointed division commander, he led the division in the occupation of Japan and for a period was Commanding General, I Army Corps. Returning to the United States, Hunt assumed duties as Commanding General, Department of Pacific and then Commanding General, FMFLant. General Hunt died in 1968.

Major General Thomas E. Bourke commanded the 5th Marine Division. Bourke was 49, a native of Robinson, Maryland, and a graduate of St. Johns College. He was commissioned in 1917 after service in the Maryland National Guard along the Mexican border. While enroute to Santo Domingo for his first tour, he and 50 recruits were diverted to St. Croix, becoming the first U. S. troops to land on what had just become the American Virgin Islands. Post-World War I tours included service at Quantico, Parris Island, San Diego, and Headquarters Marine Corps. He also served at Pearl Harbor; was commanding officer of the Legation Guard in Managua, Nicaragua; saw sea duty on board the battleship West Virginia (BB 48); and commanded the 10th Marines. Following the Guadalcanal and Tarawa campaigns, General Bourke was assigned as the V Amphibious Corps artillery officer for the invasion of Saipan. He next trained combined Army-Marine artillery units for the XXIV Army Corps, then preparing for the Leyte operation. With Leyte secured, he assumed command of the 5th Marine Division which was planning for the invasion of Japan. After the war's sudden end, the division landed at Sasebo, Kyushu, and assumed occupation duties. With disbandment of the 5th Marine Division, General Bourke became Deputy Commander and Inspector General of FMFPac. General Bourke died in 1978.

The continued cooperation of the Japanese with occupation directives and the lack of any overt signs of resistance also lessened the need for the fighter squadrons of MAG-31. Personnel and unit reductions similar to those experienced by the 4th Marines also affected the Marine air group. By the spring of 1946, reduced in strength and relieved of all routine surveillance missions by the Fifth Bomber Command, MAG-31, in early May, received orders to return as a unit to the United States. Prior to being released of all flight duties, the group performed one final task. Largely due to an extended period of inclement weather and poor sanitary conditions, the Yokosuka area had become infested with large black flies, mosquitoes, and fleas, causing the outbreak and spread of communicable diseases. Alarmed that service personnel might be affected, accessible areas were dusted with DDT by jeeps equipped with dusting attachments. The spraying effort was effective except in the city's alleys and surrounding narrow valleys, occupied by small houses and innumerable cesspools. "Fortunately we had a solution," wrote Captain Decker. MAG-31 was asked to tackle the job. "Daily, these young, daring flyers would zoom up the hills following the pathways, dusting with DDT. The children loved to run out in the open, throw wide their jackets, and become hidden momentarily in the clouds of DDT. It was fun for them and it helped us in delousing the city." On 18 June, with the final destruction of all but two of the seven wind tunnels at the Japanese First Technical Air Depot and the preparation of equipment for shipment, loading began. Earlier, the group's serviceable air craft were either flown to Okinawa, distributed to various Navy and Marine Corps activities in Japan, or shipped to Guam on the carrier Point Cruz (CVE 119). Prior to being hoisted on board, the planes made the shore to ship movement by Japanese barge equipped with a crane and operated by a Japanese crew. It was reported with amazement that "not a single plane was scratched." A small number of obsolete planes were stricken and their parts salvaged. On 20 June, the 737 remaining officers and men of MAG-31, led by Lieutenant Colonel John P. Condon, boarded the attack transport San Saba (APA-232) and sailed for San Diego. The departure of MAG-31 marked the end of Marine occupation activities in northern Japan.

|