| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

SECURING THE SURRENDER: Marines in the Occupation of Japan by Charles R. Smith Sasebo-Nagasaki Landings In the period immediately following the conclusion of the Luzon Campaign, the U.S. Sixth Army, under the command of General Walter Krueger, was engaged in planning and preparing for the invasion of Kyushu, the southernmost Japanese home island. The operation envisioned an assault by three Army corps and one Marine amphibious corps, totaling 11 Army and three Marine divisions, under the command of General Krueger. After more than three years, the major land, sea, and air components of the Central and Southwest Pacific forces were to merge in the initial ground assault against Japan itself. In early August, with the destruction of Hiroshima and the Soviet Union's entry into the war, the possibility of an early surrender increased. Although planning for the invasion continued, General MacArthur directed Krueger to also plan and prepare for the occupation of Kyushu and western Honshu should the Japanese Government capitulate. General Krueger's initial plan for the occupation called for V Amphibious Corps, commanded by Major General Harry Schmidt, to land the 2d and 5th Marine Divisions in the Sasebo-Nagasaki area on 4 September. These landings were to be reinforced later by a 3d Marine Division seaborne or overland movement to the Fukuoka-Shimonoseki area. Major General Innis P. Swift's I Corps, consisting of the 25th, 33d, 98th, and 6th Infantry Divisions, was to land three days later in the Wakayama area of western Honshu and establish control over the Osaka-Kyoto-Kobe area. The X Corps, composed of the 41st and 24th Infantry Divisions and commanded by Major General Franklin C. Sibert, was scheduled to land in the Kure-Hiroshima area of western Honshu and on the island of Shikoku on 3 October. On 14 August, the Sixth Army assumed operational control of V Amphibious Corps. After receiving official word of Japanese acceptance of the surrender demands the following day, the Corps' three divisions were informed that they should be prepared for an occupational landing in early September, and that "all units were to be combat loaded and alerted to the possibility of appreciable resistance to the occupation." The Fifth Fleet, under Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, would be responsible for collecting, transporting, and landing V Corps and other scattered elements of Krueger's army. Because of the wide dispersion of assault shipping and the magnitude of the minesweeping problem, the fleet could not move major units to their targets simultaneously and landing dates would therefore have to be postponed.

At the time of surrender there were an estimated 20,000 allied prisoners of war in Kyushu and western Honshu. Sixth Army planners contemplated that recovery teams composed of American, Australian, and Dutch representatives would accompany the occupational forces and immediately evacuate prisoners in their respective zones. Following the surrender, the Japanese virtually freed all Allied prisoners by turning the prison camps over to them and allowing them freedom of movement. Taking full advantage of the situation, many former prisoners roamed the countryside at will, creating a situation that called for an immediate change in plans. With the landing of the first American forces in Japan at the end of August, it became apparent that the evacuation of all Allied prisoners of war "must receive first priority as many of them were in poor physical condition." The revised Sixth Army plan allowed the Eighth Army to extend its evacuation program to the west and to evacuate prisoners through Osaka to Tokyo until relieved by Fifth Fleet and Sixth Army units. Prisoners on Shikoku were to be ferried across the Inland Sea to the mainland and then transported by rail through Osaka to Tokyo. The Fifth Fleet and Sixth Army immediately organized two evacuation forces consisting of suitable landing craft, hospital ships, transports, Army contact teams, truck companies, and Navy medical personnel. One force, under the command of Rear Admiral Ralph S. Riggs, landed at Wakayama on 11 September and by the 15th had completed the processing of all prisoners in western Honshu, a total of 2,575 men. The other force, commanded by Rear Admiral Frank G. Fahrion, landed at atom-bombed Nagasaki, after Fifth Fleet mine sweepers had cleared the way, and by 22 September had evacuated all 9,000 remaining prisoners on Kyushu. Preliminary examination revealed that there were no serious epidemics in the camps except for a few cases of typhoid and dysentery. Malnutrition was common and the most serious cases of beriberi and tuberculosis required immediate hospitalization. The initial processing revealed many instances of brutality. However, as it was reported at the time, "close questioning often disclosed that the prisoners had been guilty of breaking some petty but strict prison rule. A considerable number of the older men stated that the camp treatment, although extremely rugged, was on the whole not too bad. They expected quick punishment when caught for infraction of rules and got it. All complained of the food, clothing, housing, and lack of heating facilities." Except for a few stragglers, the release, medical examination, delousing, processing, and screening of Allied prisoners of war in southern Japan was completed on 23 September. While the Eighth Army extend ed its hold over northern Japan, and the two evacuation forces rounded up and processed Allied prisoners, preparations for the Sixth Army's occupation of western Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu continued. The occupation area contained 55 percent of the total Japanese population, including half of the Japanese Army garrisoning the homeland, three of Japan's four major naval bases, all but two of its principal ports, two-thirds of all Japanese cities with a population in excess of 100,000, and three of its four main transportation centers. The island of Kyushu, which was to be largely a Marine occupation responsibility, supported a population of 10,000,000 spread amongst its 15,000 square miles of mountainous terrain. The southern and eastern parts of the island were chiefly agricultural areas, producing large quantities of exportable rice and sweet potatoes. The northwestern half of the island contained almost all of southwestern Japan's coal fields, the nation's greatest pig iron and steel district, and many important shipyards, in addition to a host of other smaller industries.

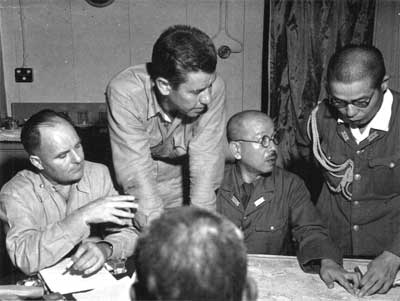

On 1 September, Major General Harry Schmidt opened his command post on board the Mt. McKinley (AGC 7), flagship of Amphibious Group 4, off Maui in the Hawaiian Islands and sailed to join the 5th Division convoy, already enroute to Saipan. The remainder of V Corps' troops, including several Army engineer augmentation units, with the exception of rear echelons, continued loading and, on 3 September, departed Hawaii for Saipan on board 17 LSTs. Schmidt's forces also carried more than 300 tons of "Military Government" or relief supplies consisting of rice, soy beans, fats and oils, salt, canned fish, and medical equipment. During the voyage to Saipan planning for the occupation continued in light of changes to the original concept of operations allowed by favorable reports of Japanese compliance with surrender terms in northern Japan and alterations in the troop list. However, every effort was made to salvage as much as possible of the content of the Olympic plans for the assault landing. On 5 September, the 3d Marine Division was deleted from the Corps' occupation force and the 32d Infantry Division substituted. To guard against possible treachery on the part of thousands of Japanese troops on bypassed islands in the Central Pacific, the Navy tasked the 3d Division, then on Guam, with preparing for any such eventuality. Meanwhile, the 2d Marine Division and additional Corps units began loading in the Marianas. "Someone at higher headquarters apparently made a gross error," noted Lieutenant Colonel Jacob G. Goldberg, the division's logistics officer. "For the first time since the war began we were assigned enough shipping to lift the entire division, and by entire division I mean 100% personnel and equipment. VAC was very much surprised that we were able to do this, and I freely admit it was a hell of a nervous strain on me up until the last ship was loaded." Early on the morning of 13 September, the various transport groups rendezvoused at Saipan. The 2d Marine Division almost was loaded and the 32d Infantry Division on Luzon was preparing to move to staging areas at Lingayen for loading on turn around shipping of the 5th Marine Division. Because of continuing indications that the landings would be unopposed, the number of air and fire support ships assigned to accompany the transport groups was reduced. The following day, General Schmidt held a conference of his subordinate commanders on board the Mt. McKinley to clarify plans for the operation. He stressed "the importance of maintaining firm, just, and dignified relations with the Japanese . . . [and] responsibilities of commanders of all echelons in following the rules of land warfare and the directives of higher authority." In view of the cooperative attitude of the Japanese thus far, permission was requested and granted to send advance parties to Nagasaki and Sasebo. Their missions were "to facilitate smooth and orderly entry of U. S. forces into the Corps zone of responsibility by making contact with key Japanese civil and military authorities; to execute advance spot checks on compliance with demilitarization orders; and to ascertain such facilities for reception of our forces as condition and suitability of docks and harbors; adequacy of sites selected by map-reconnaissance for Corps installations; condition of airfields, roads, and communications." The first party, led by Colonel Walter W. Wensinger, VAC operations officer, and consisting of key Corps and 2d Division staff officers flew via Okinawa to Nagasaki, arriving on 16 September. A second party of similar composition, but with underwater demolition teams and 5th Division personnel attached, left for Sasebo by high speed transport on 15th. After meeting with local officials, spot checking coastal defenses, and arranging for suitable barracks, warehouse, and command post sites, Colonel Wensinger and his staff proceeded by destroyer to Sasebo where they made preliminary arrangements for the 5th Division's arrival. On 20 September, the second reconnaissance party arrived at Sasebo where it was met by Wensinger's party, and completed preparations for the landing.

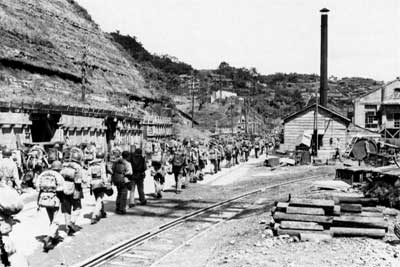

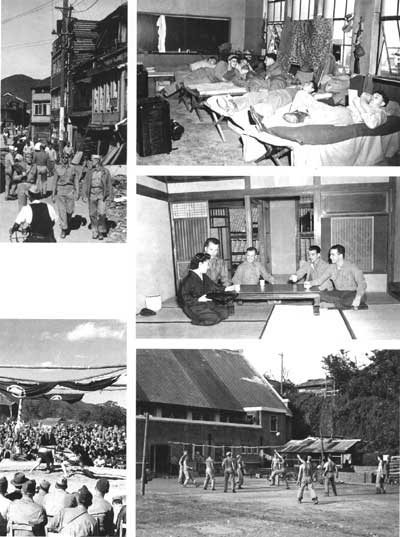

At dusk on 16 September, Transport Squadron 22 bearing the Corps headquarters and 5th Marine Division slipped out of Tanapag Harbor bound for Sasebo. The landing ships carrying elements of the 2d Marine Division left Saipan for Nagasaki the next day. During the eventful voyages, Marines received refresher training in military discipline and courtesy and got their initial briefs on the Japanese people, customs, and geography. Early on 22 September, the transport squadron carrying Major General Thomas E. Bourke's 5th Marine Division and corps headquarters troops arrived off Sasebo Harbor. They were met by Colonel Wensinger and members of the advance party together with Japanese pilots who were to guide the ships into their assigned berthing and docking areas. The advance party representatives were transferred to their respective unit command ships where they made their reports which required changes in billeting plans, making it necessary that 3d Battalion, 26th Marines remain afloat. At 0859, after Japanese pilots had directed the transports to safe berths in Sasebo's inner harbor, the 26th Marines, less the 3d Battalion, landed on beaches at the naval air station. Advancing rapidly inland, the Marines moved to areas tentatively selected at Saipan from aerial photographs and verified by the advance party. Unarmed Japanese naval guards on base installations, arms, and stores were relieved and Japanese guides arranged for by the advance party directed the Marines to pre-selected billeting areas. Ships carrying other elements of the division then moved to the Sasebo docks to begin general unloading. The shore party, reinforced by the 2d Battalion, 28th Marines, was ashore by 1500 and began cargo unloading operations which continued throughout the night.

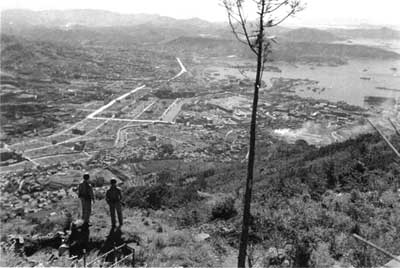

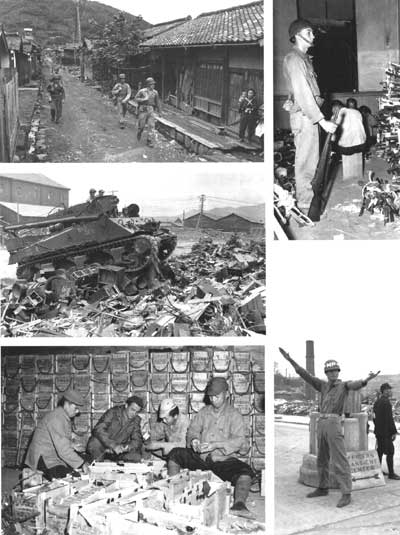

The remainder of the 28th Marines, in division reserve, remained on board ship. The 1st Battalion, 27th Marines landed on the docks in late afternoon and moved out to occupy the regiment's assigned zone of responsibility. During the afternoon, Generals Bourke, Schmidt, and Krueger inspected the occupation's progress with tours of the naval station, city of Sasebo, and naval air station. Before troop unloading was suspended at dusk, 1st and 2d Battalions, 13th Marines had landed on beaches in the aircraft factory area; 5th Tank Battalion had come ashore at the air station; and the assistant division commander and his staff had established an advanced division command post at the Sasebo Fortress. The main division command post remained afloat to control unloading better. All units ashore established guard posts and security patrols, but the division's first night in Japan was uneventful. Sasebo, the home of the third largest naval base in Japan, was a city of more than 300,000 prior to 29 June 1945. That day, the city suffered its only B-29 raid of the war which destroyed a large portion of the city's shopping and business districts. The naval area was largely undamaged. More than 60,000 were made homeless and approximately 1,000 people were killed. The Marines saw very few of the remaining 166,000 inhabitants. "There wasn't a damn soul in town except those black coated policemen," General Ray A. Robinson later noted, "and there was one of those on every intersection. There wasn't another person in sight and it was very eerie." The few policemen and naval guards were described as being "acquiescent and docile with little expression of emotion or show of interest."

The city was described as unbearable due to the stench rising from refuse piled high throughout. But as Bourke's Marines began the arduous task of cleaning up, Sasebo and the attitude of its inhabitants changed, as Marine Lieutenant Edwin L. Neville, Jr., later recalled:

On 23 September, as most of the remaining elements of the 5th Division landed and General Bourke set up his command post ashore, sanitary squads prepared billeting areas and patrols started probing the immediate countryside. Company C, 1st Battalion, 27th Marines, was sent by amphibian trucks to Omura, about 22 miles southeast of Sasebo, to establish a security guard over the aircraft assembly facilities and repair 2 training base "to prevent further looting by Japs." Omura's 5,000 by 4,000 foot, "cow-pasture variety" airfield had been selected as the base of Marine air operations in southern Japan.

A reconnaissance party, led by Colonel Daniel W. Torrey, commanding officer of Marine Aircraft Group 22 (MAG-22), had landed and inspected the field on 12 September, and the 600-man advance echelon had flown in from Chimu on Okinawa six days later. The echelon found a considerable number of enemy planes ranging from beaten up "Willows," the Japanese version of the Boeing-Stearman Kaydet trainer, to combat aircraft consisting of "Jacks," "Georges, and "Zekes," all lacking just enough parts to be inoperable. Twenty-one Corsairs of Marine Fighter Squadron 113 reached Omura on the 23d, after a two-day stop-over at Kanoya airfield on Kyushu due to bad weather. The rest of the group's flight echelon, composed of Marine Fighter Squadrons 314 and 422 and Marine Night Fighter Squadron 543, arrived before the month was over. Each squadron was assigned two hangars, one for storing and servicing its planes and the other for quartering enlisted men and messing facilities. MAG-22's primary mission was similar to that of MAG-31 at Yokosuka — surveillance flights in support of occupation operations. As MAG-22 began flight operations from Omura and the 5th Division consolidated its hold on Sasebo, the second major element of Schmidt's amphibious corps landed in Japan. The early arrival of the ships of Transport Squadron 12 at Saipan, coupled with efficient staging and loading, had enabled planners to move the 2d Marine Division's landing date forward three days. When reports were received that the approaches to the originally selected landing beaches were mined but that Nagasaki's harbor was clear, the decision was made to land directly into the harbor area. At 1300 on 23 September, the 2d and 6th Marines, in full combat kit with fixed bayonets and full magazines, landed simultaneously on the east and west sides of the harbor. Nagasaski, as one Marine observed, "can be described very easily: It is a filthy, stinking, wrecked hole, and the sooner we get out the better we'll all like it."

Relieving the Marine detachments from the cruisers Biloxi (CL 80) and Wichita (CA 45), which had been serving as security guards for the prisoner of war evacuation operations, the two regiments moved out swiftly to occupy the city. Their second objective was to cordon off the area devastated by the atomic bomb. As Lieutenant Colonel George L. Cooper later recalled: "Ground zero appeared to have been a rather large sports stadium, and all of us were categorically ordered to stay out of any place within pistol shot of this area. The result of this order was that everybody and his brother headed directly for ground zero as soon as they could, and in no time at all had picked the area clean of all moveable objects." Later, ships were brought alongside wharfs and docks to facilitate cargo handling, and unloading operations were well under way by nightfall. A quiet calm ruled the city, auguring a peaceful occupation.

On 24 September, the rest of Major General LeRoy P. Hunt's 2d Division landed. The 8th and 10th Marines, the last of the division's regiments to land, and Marine Observation Squadron (VMO) 2, passed through Nagasaki, moved northeast to Isahaya, and seized control of the area. Once it had completed its movement into Nagasaki and Isahaya, the 2d Marine Division dispatched reconnaissance patrols to check the road conditions from Isahaya through Omuta to Kumamoto. The same day, the corps commander arrived from Sasebo by destroyer to inspect the Nagasaki area. General Schmidt had established his command post ashore at Sasebo the previous day and taken command of the two Marine divisions. The only other major allied unit ashore on Kyushu, a reinforced Army task force that was occupying Kanoya airfield in the southernmost part of the island, was transferred to General Schmidt's command from the Far Eastern Air Force on 1 October. This force, built around the 32d Infantry Division's 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, had flown into Kanoya on 3 September to secure an intermediate airstrip for staging and refueling aircraft enroute from the Philippines and Okinawa to Tokyo. General Krueger, satisfied with the progress of the occupation on Kyushu. assumed command of all forces ashore at 1000 on 24 September. The following day, Headquarters I Corps and the 33d Infantry Division, the first major elements of Sixth Army's other corps, arrived and began landing operations at Wakayama. Head quarters Sixth Army landed with Major General Swift's troops and on the 27th opened at Kyoto. At Sasebo, Nagasaki, and Wakayama, there was ample evidence that the occupation of southern Japan would be bloodless.

Like the Marines and sailors of General Clement's command at Yokosuka, those under the command of General Schmidt expected the worse. The only experience most had was in battle, during which the Japanese often refused to surrender and were annihilated. But like Clement's, Schmidt's forces were amazed at what they encountered. "We couldn't believe the Japanese could previously fight so ferociously and then be so completely subservient, without a murmur," Brigadier General Joseph L. Stewart later recalled. "Not once did I see any Japanese who acted or looked with disrespect toward occupation forces . . . . We were overwhelmingly surprised by the cooperative reception we had from the Japanese."

|